Factors Influencing Teachers’ Implementation of a Reformed Instructional Model in China from the Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective: A Multiple Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Factors Influencing Teachers’ Implementation of Curriculum Reform

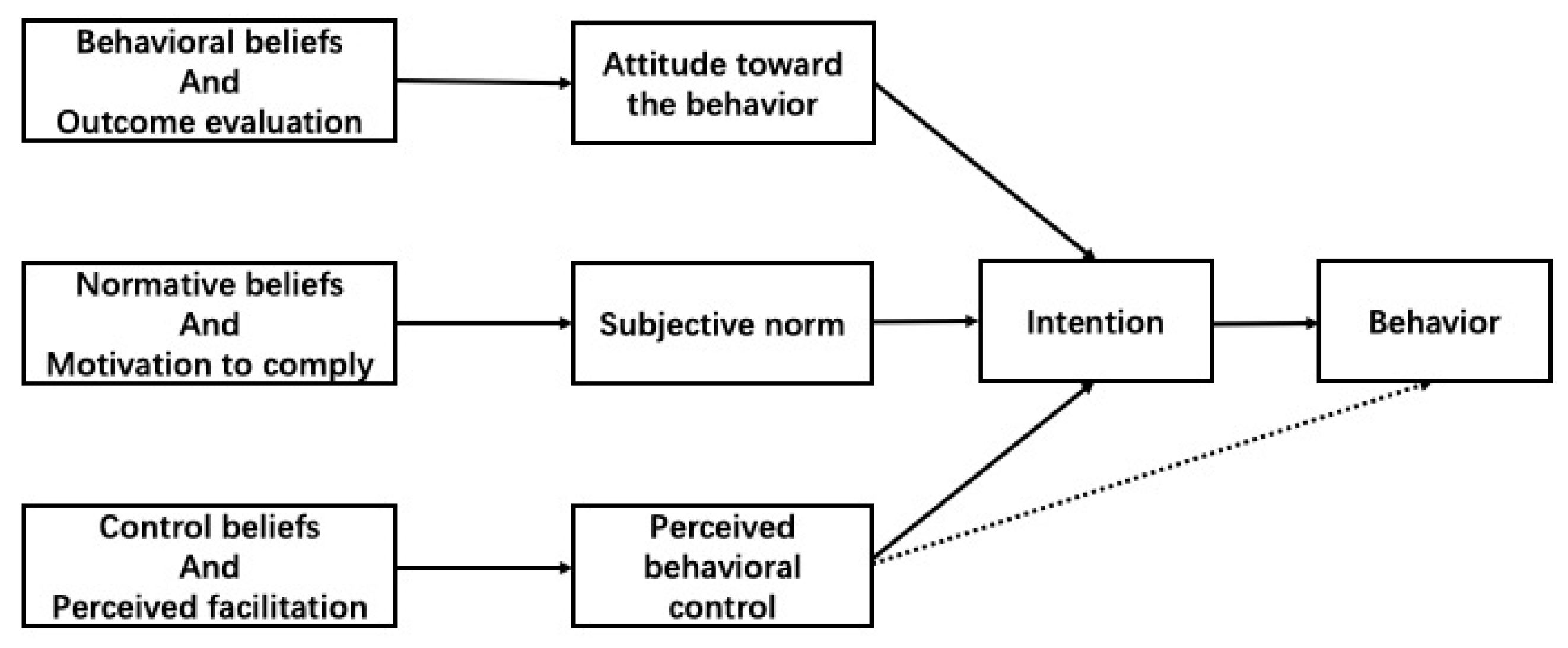

2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior Framework

2.2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior Application in Educational Reform Research

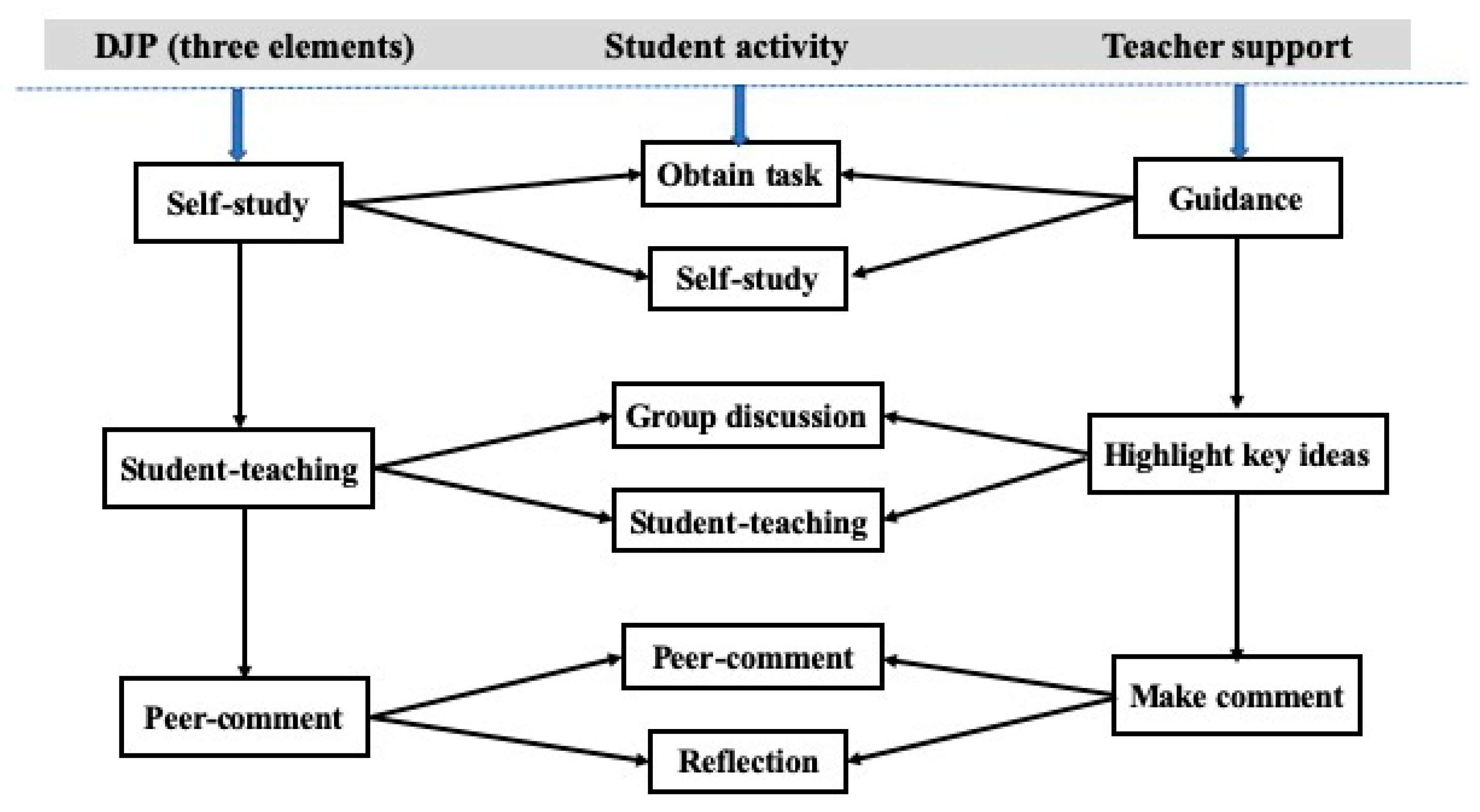

3. The DJP Model

3.1. Basic Procedures of the DJP Model

3.2. Comparison among Chinese Traditional Classrooms, DJP Model Classrooms and Student-Centered Classrooms

4. Research Method

4.1. Site

4.2. Overall Design of the Longitudinal Project

4.3. Research Design of Phase 2

4.3.1. Participants

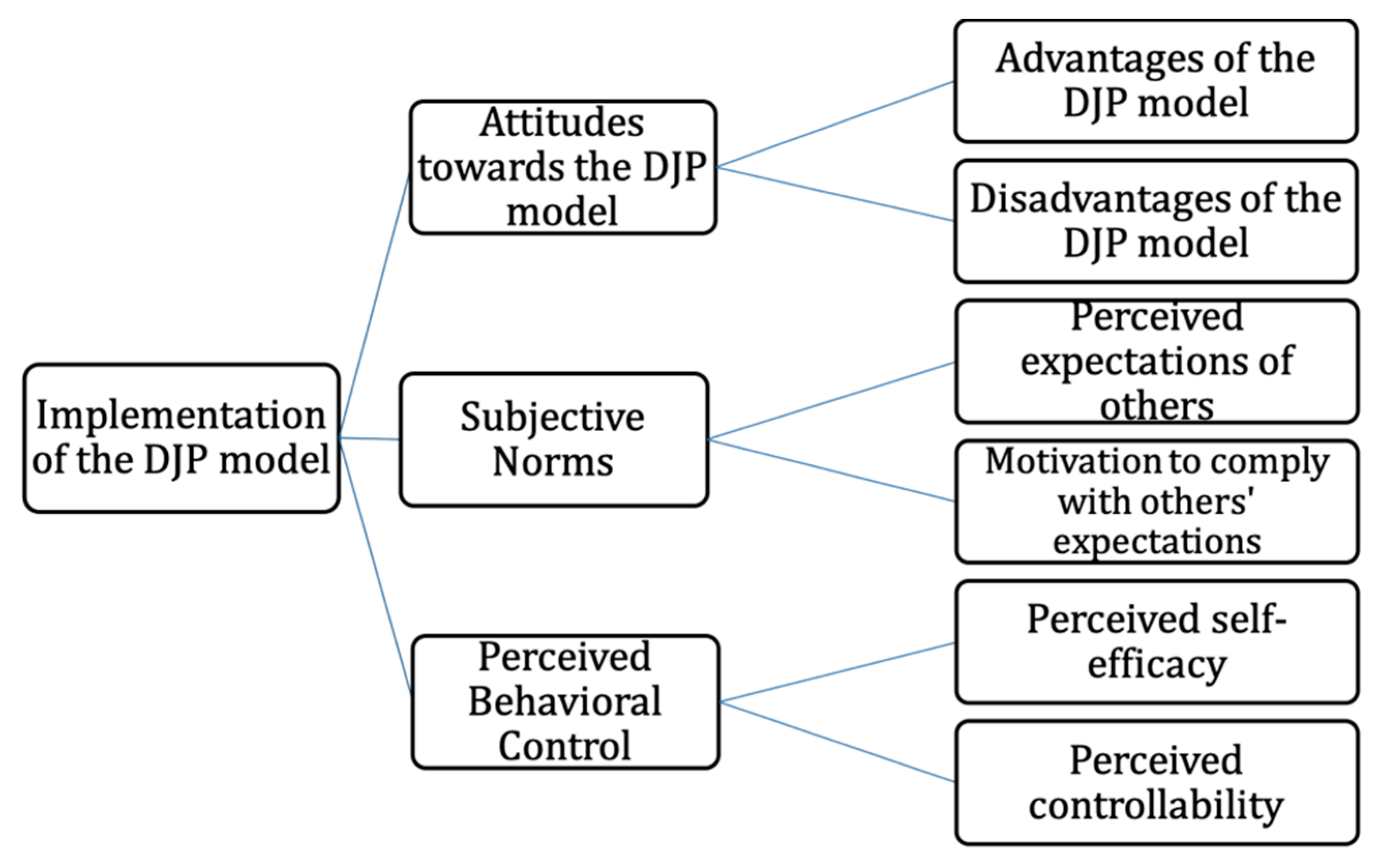

4.3.2. Data Collection

- (1)

- What do you think of the DJP model? What are the advantages and disadvantages of the DJP model? (Attitude towards the behavior);

- (2)

- What are the expectations of your school leaders, colleagues and students in terms of your DJP implementation? What are your attitudes towards their expectations? (Subjective norms);

- (3)

- What are the helpful factors and difficulties in terms of DJP implementation? (Perceived behavior control).

4.3.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

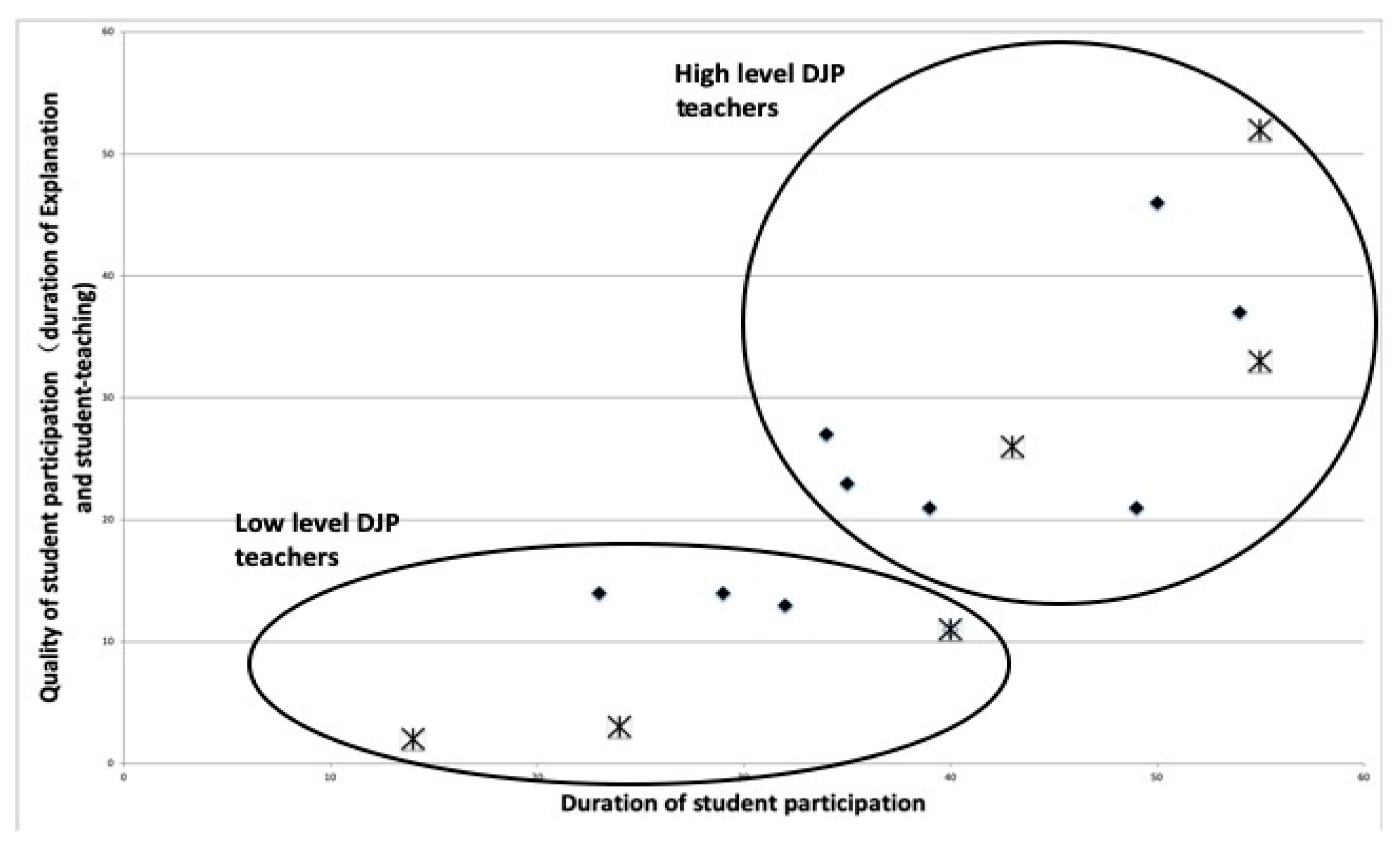

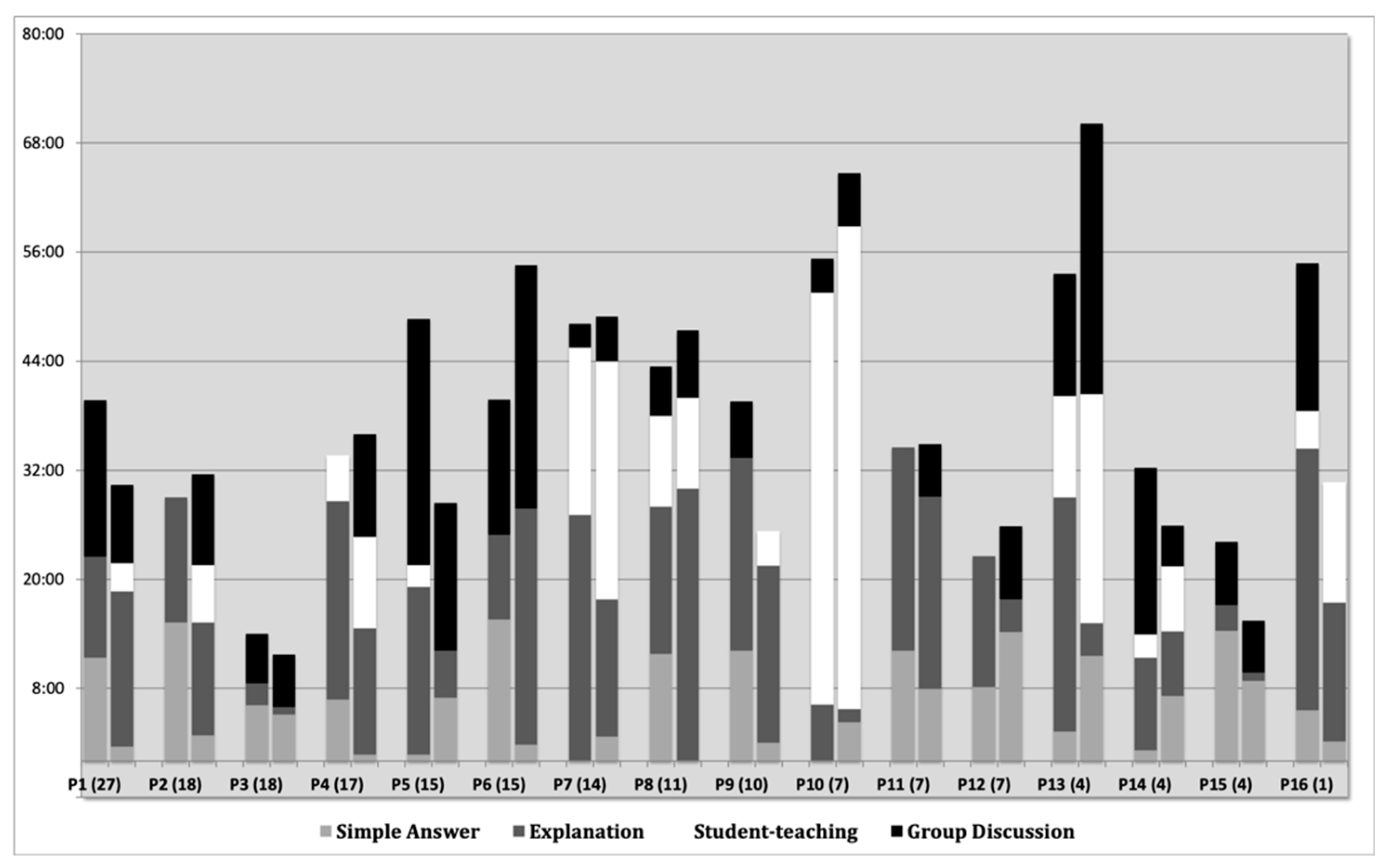

5.1. Phase 1: Levels of Implementation of DJP Model

5.2. Phase 2: Factors Influencing Teachers’ Levels of Implementation of DJP Model

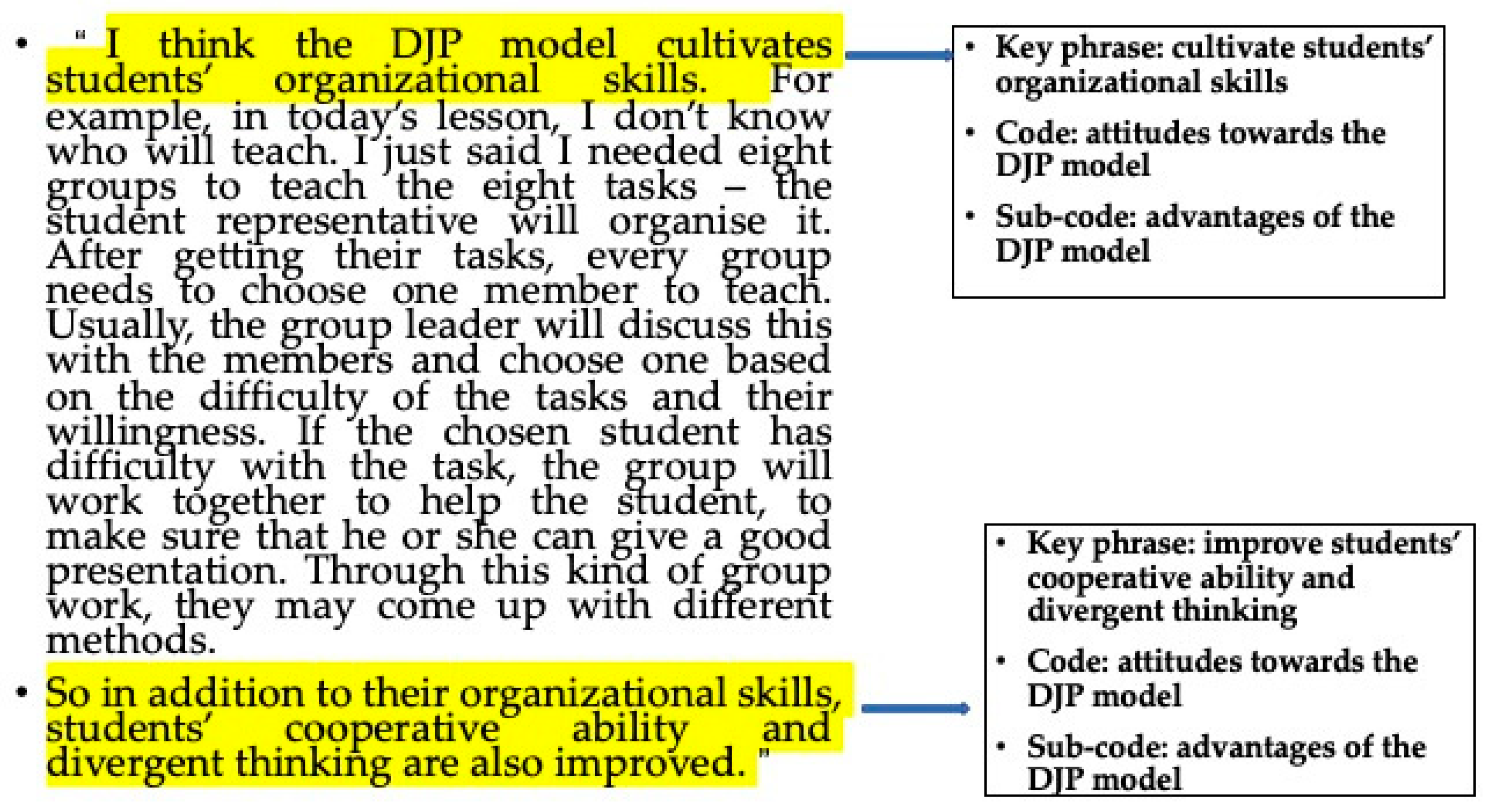

5.2.1. Attitudes

I think the DJP model cultivates students’ organizational skills. After getting the tasks, every group needs to choose one member to teach. Usually, the group leader will discuss this with the members and choose one based on the difficulty of the tasks and their willingness. If the chosen student has difficulty with the task, the group will work together to help the student, to make sure that he or she can give a good presentation. Through this kind of group work, they may come up with different methods. So, in addition to organizational skills, students’ cooperative ability and divergent thinking are also improved. (T1)

We know that foreign countries even import mathematics teachers from China because they think our mathematics education is good. Our students perform very well, which is not because of the DJP model, right? It is because of our traditional teaching! I think we need to keep the virtues of our education. For our country, because of our tradition and big classes, it is impossible for one reform or one model to change the system. I still think traditional education is good.

5.2.2. Subjective Norms

I observed some DJP lessons, I think it is very good. But you know, their students are high-ability students, not like our students. I think our students are too poor to do the DJP. They can just present what they had, it is very difficult to train them to explain the ideas clearly and act as a teacher. It is too difficult. (T4)

The benefits of the DJP model depend on different students. Good students know how to solve the problem, and they can teach. Poor students, when they speak, most of their thoughts are wrong, so they are afraid that other students will laugh at them. So not all students can be trained as “little teachers.” Also, some students are not good at explaining their ideas, so other students just do not want to listen.

5.2.3. Perceived Behavioral Control

The biggest problem for some teachers is that they think students teach very slowly; the time is wasted and the other students learn nothing. My opinion is different. You finish all the content, but that does not mean the students have command of all the content and their abilities have improved. What I teach is not just knowledge, but also ability. For example, self-study is very important in the DJP model. After they have this ability, they can learn by themselves. (T2)

If you want students to explain clearly, they need to put a lot of effort into it. Now students have so many classes—five classes in the morning, five classes in the afternoon, classes at noon and in the evening. How can students find time to think about problems deeply and prepare for teaching? I think this thing [the DJP model] is too idealistic. (T5)

It is impossible to train every student into a “little teacher.” It is not realistic. You have so many teaching tasks, and you need to care about teaching progress and worry about students’ performance in exams. So, you need to deal with it flexibly. I will not use this model in every lesson. (T6)

5.2.4. An additional Dimension: Teachers’ Understanding of the DJP Model

I feel that maybe I consciously cultivate students’ ability to summarize the mathematics methods and think through the process of problem solving. The students in my class know the terms of these methods and can explain how and why to use them, while in other teachers’ classes, their students know how to solve the problems but are not aware of the methods they are using. I think this may be because I always require them to summarize their methods in the problem-solving process.

Sometimes, students cannot clearly explain the methods, the variations of problems and the connection of the new knowledge with previous knowledge. In this case, as a teacher, I should make it clear. This high level of teaching should be provided by the teacher to supplement students’ explanation.

6. Conclusions

- Individual factors that relate to teachers’ attitudes, beliefs, self-efficacy and understanding of the reform.

- Perceived social factors that relate to teachers’ perceived subjective norms, including school culture, the support of school leaders and the motivation and attitudes of students.

- Perceived contextual factors that relate to teachers’ perceived behavioral control, including the effectiveness and operability of the DJP model, and pressure from exams, heavy workload and time limits.

7. Discussion

7.1. Theoretical Attribute of the TPB Framework

7.2. How to Get Teachers to Implement Reform Ideas Sustainably

7.3. Implication for Teachers’ Professional Development Programs

7.4. Limitation

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Appendix: Examples from DJP Classrooms

Student 1: From example 1 and example 2, we can see in this formula that a and b can be numbers, monomials and polynomials. The first example is (2009 + 1)(2009 − 1), in which a and b are numbers; the second example is (m + n)(m – n) in which a and b are monomials; the third example is [(x – m) – (n + c)][(x – m) + (n – c)], in which a and b are polynomials. When we use this formula, we need to make sure it is a product, and it has something like a + b and something like a – b. Also, be careful to put the a first and the b second, which makes the answer .

References

- Li, Y.; Lappan, G. Mathematics Curriculum in School Education; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld, A.H. Reflections on curriculum change. In Mathematics Curriculum in School of Education; Li, Y., Lappan, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Buchs, C.; Filippou, D.; Pulfrey, C.; Volpé, Y. Challenges for cooperative learning implementation: Reports from elementary school teachers. J. Educ. Teach. 2017, 43, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Villarreal, F.; Rodriguez, B.J.; Moore, S. Teachers’ perceptions and attitudes about Response to Intervention (RTI) in their schools: A qualitative analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2014, 40, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M. The New Meaning of Educational Change, 3rd ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wyss, C.; Kocher, M.; Baer, M. The dilemma of dealing with persistent teaching traditions: Findings of a video study. J. Educ. Teach. 2017, 43, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maass, K.; Cobb, P.; Krainer, K.; Potari, D. Different ways to implement innovative teaching approaches at scale. Educ. Stud. Math. 2019, 102, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, J. Teacher education changes in China: 1974–2014. J. Educ. Teach. 2014, 40, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. Curriculum Standards for Mathematics Curriculum of Nine-Year Compulsory Education (Experimental Version); Beijing Normal University Press: Beijing, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Ni, Y. Impact of curriculum reform: Evidence of change in classroom practice in mainland China. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2011, 50, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. Curriculum Standards for Mathematics Curriculum of Nine-Year Compulsory Education; Beijing Normal University Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H. Implementing the national curriculum reform in China: A review of the decade. Front. Educ. China 2013, 8, 331–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, Y. Mathematics curriculum reform in the Chinese mainland: Changes and challenges. In Reforms and Issues in School Mathematics in East Asia: Sharing and Understanding Mathematics Education Policies and Practices; Leung, F.K.S., Li, Y., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, Boston, USA, 2010; pp. 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Zou, J. China’s new millennium curriculum reform in mathematics and its impact on classroom teaching and learning. Impact Transform. Educ. Policy China 2011, 15, 99–124. [Google Scholar]

- He, G.F.; Gao, X. Analysis on the difference between the teaching concept and the teaching behavior of mathematics teachers in junior middle schoolbased on video analysis of 15 mathematics lessons in middle school. J. Math. Educ. 2013, 22, 24–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, F. Standards-based instruction: Status, reflection and strategy. Curric. Teach. Mater. Method 2012, 32, 9–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y. The implementation process, characteristics analysis and promotion strategy of the curriculum reform of basic education. Curric. Teach. Mater. Method 2019, 29, 3–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Wang, X. How students learn knowledge from classroom interaction. Math. Educ. China 2013, 11, 3–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, P.R. Teacher beliefs and intentions regarding the instruction of English grammar under national curriculum reforms: A Theory of Planned Behaviour perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhendal, D.; Marshman, M.; Grootenboer, P. Kuwaiti science teachers’ beliefs and intentions regarding the use of inquiry-based instruction. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2016, 14, 1455–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgonjon, J.; De Grove, F.; De Smet, C.; Van Looy, J.; Soetaert, R.; Valcke, M. Acceptance of game-based learning by secondary school teachers. Comput. Educ. 2013, 67, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, K.; Woolfson, L.M. Teacher attitudes and behavior toward the inclusion of children with social, emotional and behavioral difficulties in mainstream schools: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 29, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cloud, J. The Essential Elements of Education for Sustainability (EFS): Editorial Introduction from the Guest Editor. 2014. Available online: www.susted.com/wordpress/content/the-essential-elements-of-education-for-sustainability-efs_2014_05/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Spillane, J.P.; Reiser, B.J.; Gomez, L.M. Policy implementation and cognition. In New Directions in Education Policy Implementation; Honig, M.I., Ed.; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Buabeng-Andoh, C. Factors influencing teachers’ adoption and integration of information and communication technology into teaching: A review of the literature. Int. J. Educ. Dev. Using Inf. Commun. Technol. 2012, 8, 136–155. [Google Scholar]

- Thurlings, M.; Evers, A.T.; Vermeulen, M. Toward a Model of Explaining Teachers’ Innovative Behavior A Literature Review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2015, 85, 431–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.P.; Reiser, B.J.; Reimer, T. Policy implementation and cognition: Reframing and refocusing implementation research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2012, 72, 387–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spillane, J.P.; Zeuli, J.S. Reform and teaching: Exploring patterns of practice in the context of national and state mathematics reforms. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1999, 21, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. In Handbook of Theories of Scocial Psychology: Volume 1; Van Lang, P.A.M., Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E., Eds.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 438–459. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Attitude structure and behavior. In Attitude Structure and Function; Pratkanis, A.R., Breckler, S.J., Greenwald, A.G., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1989; pp. 241–274. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-Y.; Williams, P.J. Taiwanese Preservice Teachers’ Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Teaching Intention. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2016, 14, 1021–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pynoo, B.; Tondeur, J.; Van Braak, J.; Duyck, W.; Sijnave, B.; Duyck, P. Teachers’ acceptance and use of an educational portal. Comput. Educ. 2012, 58, 1308–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milner, A.R.; Sondergeld, T.A.; Demir, A.; Johnson, C.C.; Czerniak, C.M. Elementary teachers’ beliefs about teaching science and classroom practice: An examination of pre/post NCLB testing in science. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2012, 23, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaf, A.; Newby, T.J.; Ertmer, P.A. Exploring pre-service teachers’ beliefs about using Web 2.0 technologies in K-12 classroom. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Hwang, S. Characterizing Mathematics Education in China: A perspective on Improving Student Learning. In The First Sourcebook on Asian Research in Mathematics Education: China, Korea, Singaplore, Japan, Malaysia, and India; Sriraman, B., Cai, J., Lee, K.-H., Fan, L., Shimizu, Y., Lim, C.S., Subramaniam, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Dong, L.; Li, X. A Study of Mathematics Classroom Teaching in China: Looking at Lesson Structure, Teaching and Learning Behavior. In The 21st Century Mathematics Education in China; Cao, Y., Leung, F.K.S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 195–222. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, F.K.S. Some characteristics of East Asian mathematics classrooms based on data from the TIMSS 1999 video study. Educ. Stud. Math. 2005, 60, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, I.A.C. Shedding light on the East Asian learner paradox: Reconstructing student-centredness in a Shanghai classroom. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2006, 26, 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Clarke, D.; Cao, Y.; Wang, L.; Seah, W. Teacher Questioning Practices over a Sequence of Consecutive Lessons: A Case Study of Two Mathematics Teachers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, F. Walking between Theories and Practices: A Collection of Research on the DJP Model; Southwest Jiaotong University Press: Chengdu, China, 2019. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Breault. Active Learning: A Growth Experience. In Experiencing Dewey: Insights for Today’s Classroom; Breault, D.A., Breault, R., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Schweisfurth, M. Learner-centred education in international perspective. J. Int. Comp. Educ. 2013, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C. Beyond ‘either-or’ thinking: John Dewey and Confucius on subject matter and the learner. Pedagog. Culture Soc. 2016, 24, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Mok, I.A.C.; Cao, Y. Curriculum reform in china: student participation in classrooms using a reformed instructional model. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 75, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remillard, J.T. Examining key concepts in research on teachers’ use of mathematics curricula. Rev. Educ. Res. 2005, 75, 211–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fang, Z. A review of research on teacher beliefs and practices. Educ. Res. 1996, 38, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, P. Managing Change in Schools; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

| Chinese Traditional Classroom [38,39,40,41,42] | DJP Model Classroom [18,43] | Student-Centered Classroom (Western Model) [44,45,46] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning content | Standardized content High-cognitive-demand tasks Careful task design with variation | Standardized content High-cognitive-demand tasks Careful task design with variation | Diverse tasks depending on students’ different abilities Learning content linked to students’ lives |

| Roles of teacher and students | Teacher plays a central role Students are cognitively engaged but do not talk much | Teacher as guide, facilitator and co-operator Students play a central role, acting as “little teachers” (student-teaching) | Teacher as facilitator Students play a central role |

| Classroom activities | Emphasizes teacher’s explanations Coherent lesson design Lecturing Lack of interaction and collaboration between students Lack of exploration activities | Self-study by students before the lesson Students present and explain their work Teacher guides, highlights and enriches students’ explanations Emphasizes student–student interaction (peer-comment) Group work and discussion Active student participation Coherent lesson design | Self-exploration Group work Presentation and explanation by students Debate Active student participation Communication and cooperative activities |

| Classroom interaction | Teacher–whole class interaction Teacher–individual interaction (teacher asks closed-ended questions and students provide short answers, often in choral responses) | Teacher–whole class interaction Teacher–individual interaction Student–student interaction through group work and peer comments (both teacher and students pose questions in class and students explain their answers in detail) | Teacher–individual interaction Student–student interaction through group work and discussion |

| Assessment | Summative assessment (knowledge acquisition) | Summative assessment (knowledge acquisition) Formative assessment (group work, presentation) | Formative assessment (project work, presentation, speech, collaborative activities) |

| Level | Duration of Student Participation | Quality of Student Participation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Among the 80 min of class time (two consecutive lessons), the duration of student participation is more than 30 min | and | Duration of explanation and student teaching is more than 15 min |

| Low | Among the 80 min of class time (two consecutive lessons), the duration of student participation is less than 30 min | or | Duration of explanation and student teaching is less than 15 min |

| Teacher | Gender | Years of Teaching (by 2016) | Level of Students | Level of DJP Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Female | 11 | Average | High |

| T2 | Female | 10 | Below average | High |

| T3 | Male | 19 | Average | High |

| T4 | Female | 22 | Below average | Low |

| T5 | Female | 4 | Average | Low |

| T6 | Female | 22 | Average | Low |

| T1, T2, T3 | T4, T5, T6 | Major Concerns (Factors) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude: advantages and disadvantages of the model |

|

|

|

| Subjective norms: perceived expectations of school leaders and students, and motivation to comply |

|

|

|

| Perceived behavioral control: perceived self-efficacy and controllability |

|

|

|

| Additional dimension: interpretation of the model |

|

|

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, W.; Mok, I.A.C.; Cao, Y. Factors Influencing Teachers’ Implementation of a Reformed Instructional Model in China from the Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective: A Multiple Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010001

Zhao W, Mok IAC, Cao Y. Factors Influencing Teachers’ Implementation of a Reformed Instructional Model in China from the Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective: A Multiple Case Study. Sustainability. 2020; 12(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Wenjun, Ida Ah Chee Mok, and Yiming Cao. 2020. "Factors Influencing Teachers’ Implementation of a Reformed Instructional Model in China from the Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective: A Multiple Case Study" Sustainability 12, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010001

APA StyleZhao, W., Mok, I. A. C., & Cao, Y. (2020). Factors Influencing Teachers’ Implementation of a Reformed Instructional Model in China from the Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective: A Multiple Case Study. Sustainability, 12(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010001