1. Introduction

It seems that throughout the majority of the 20th century, heritage protection and spatial planning, to say the least, were conflicting concepts. Many global, European and national cultural heritage protection agendas, scientific research, as well as realized examples of the sustainable use of heritage, all promote the integration of these two fields.

Spatial planning has gone through major transformations in the 1990s, from the rational planning model [

1] to the communicative-collaborative model in which various interests, through open communication and dialogue, should contribute to the planning process for coming to a consensus [

2,

3]. However, Fainstein [

4] has a contrasting view, noticing that even when all stakeholders are not involved in participatory processes in the conceptualization phase of the projects, autocratic and bureaucratic ways of project creation can bring desired positive and just outcomes, with a precondition that none of the interests, except for the interests concerning the benefit of the community, are present. These shifts in urban governance generated a need for building new networks between independent organizations and development of their capacity to act outside of their formal competencies to adapt to each specific situation [

5]. The strategic approach in networking underlines the

complementary element to the formal administrative structures regarding informal relations which could have a decisive role in achieving all actors’ objectives and reaching favorable solutions [

6].

Furthermore, spatial planning has abandoned the strategic approach in the development of cities in the 1980s to move towards flagship projects of the transformation of urban landscapes in order to leave behind rigid comprehensive plans of an earlier period [

7]. Nevertheless, an integrated approach to spatial governance and urban development emerged and Healey [

8] argues that it is not possible to approach urban development through isolated large projects, but rather with the integration of economic, social and environmental aspects to develop the long-term strategic framework. Therefore, at the end of the 20th century, strategic spatial planning was given attention once again due to the competitiveness of urban regions and the introduction of sustainable development, among other things, in order to re-imagine a city prioritizing area investment, conservation measures, strategic infrastructure investments and principles of land use regulation [

7] (pp. 45–46). As such, strategic planning focuses on defining priority issues from the long-term perspective [

9]. Since it is concerned with benefits and impacts for the community on the large scale, strategic planning seeks for performance as the outcome of the process, and searches for a cross-sector approach from different spatial, economic and social policies to tackle various aspects of development in an integrated way [

10]. Additionally, Vedung [

11] argues that choosing a unique combination of several policy instruments is one of the most difficult and yet essential issues in the strategic political planning and conceptualizes policy instruments as regulations, economic means, and information.

Regarding planning and urban development, a significant number of big cities use large regeneration projects, competing against each other, to attract private investments and international companies to promote the city as a good place in which to live, while exercising new entrepreneurial forms of governance in liberal capitalism [

12,

13]. However, the situation with small cities and their governments is entirely different, since they have to find other means for the revival of their urban fabric. Furthermore, the global restructuring, de-industrialization of the economy, the transition from industrial to post-industrial production, networked society and migration processes are generating a growing number of urbanized cities worldwide where traditional industrial production has been abandoned and populations have decreased.

These global restructuring processes have an impact on the spatial-economic distribution of urban activities on the local city level as well, since, many built assets do not have contemporary or formal use for it at all. Besides other urban land uses, important for this research are the location of former industrial compounds, single industrial heritage buildings and traditional rural residential estates. Those assets were usually located at the edges of the central city cores, while nowadays they are left abandoned as large-scale derelict areas of land or small isolated islands within the historic urban fabric.

Thus, the attention for the regeneration process of historic cores of the cities has changed from the protection towards regeneration and the integration of two fields [

14]. Building on these grounds, that planning and protection should be integrally treated in the urban redevelopment, we go further and argue that the strategic planning should use heritage as the generative and dynamic asset for the city revival processes. The relation between heritage, planning and design is not new, but a contemporary understanding of heritage goes beyond protection and is more concerned with historic urban landscapes. Accordingly, by focusing on relations between sustainable development and strategic spatial planning, which includes urban design as a place making process, we turn to the relatively new model and the concept of the heritage urbanism. Heritage urbanism [

15] (p. 12–14) considers urban heritage as comparable to other infrastructures within cities as a valuable systems approach which acts as a regenerative layer and a common good for the development of the contemporary city. Heritage urbanism, seen it that way, can also contribute to the sense of place, attachment and recreate lost social bonds within the community.

Additionally, the role of building conservation has changed from the preservation aspects alone toward the adaptive reuse of heritage as a strategy for urban regeneration and sustainability [

16]. Adaptive reuse of heritage, seen in a contemporary way, places the imperative on different aspects of sustainability and the degree of community development in the process of heritage reuse and preservation of its socially recognized values [

17]. Adaptive reuse is a process of modifying a place to suit the existing or new use of derelict or abandoned buildings without diminishing the value of the old and that protects cultural and historical values, while simultaneously recognizing the essential dynamic of a property [

18]. Thus, building on Cooper’s [

19] arguments, Bullen and Love [

16] (p. 412) suggest that the practical outcomes of the adaptive reuse and conservation support the reuse of heritage buildings as a sustainable strategy. Included in it are improvements in environmental aspects related to the material and resource efficiency, cost reductions for economic sustainability and retention as social sustainability.

Nevertheless, there are also some authors claiming that adaptive reuse strategies should be created to use traditional houses “with their original functions or appropriate functions with the authenticity of the original function” [

20] (p. 12). This approach is not well suited for the contemporary tendencies shown above that combine adaptive reuse with the new compatible uses.

In this paper, we analyze three cases of different levels of adaptive reuse of heritage buildings, according to the new functions and the extent of preserving their historic character and significance. Terra Panonica is a new contemporary urban program and setting in a rural environment on the traditional residential estate with vernacular architecture. Terra—Center for Fine and Applied Arts is an urban program and setting on a former industrial compound in an urban environment. Suvača the horse-powered mill, is the single industrial heritage building of high significance and a cultural monument with a former rural program and setting in an urban environment with temporary activated cultural and educational activities.

The main question presented here is how to adaptively reuse heritage as the new generative value for sustainable urban development which respects heritage values, authenticity and identity and at the same time, have a profound positive impact on local communities in terms of economic, social and spatial gains.

Thus, we argue in this paper that the new contemporary urban programs, usage and activities considered here as urban acupuncture for the adaptive reuse of urban heritage can act as a generator for sustainable urban development and revival. This concept is constructed and shaped by the integral’s urbanism main idea which: “proposes more punctual interventions that contribute to activating places (enhancing flow) by making connections and caring for neglected or abandoned ‘in-between’ spaces or ‘no-man’s land’s” [

21] (p. 9). Seen in such a way, heritage urbanism, as we understand it and apply in this paper, is understood as urban redevelopment and adaptive reuse of heritage nodes through the creation of new employment opportunities, creation of social networks and protection of traditional values and the identity and quality of place. For our analysis, we employ either architectural and industrial heritage (Suvača), former industrial sites (Terra) or a traditional typical rural compound (Terra Panonica) with new contemporary uses to assess whether they can act as a generator for urban revival.

In relation to heritage urbanism, throughout this paper we use the term node to refer to the spatial element of urban heritage in the network at which physical connections or communication lines among different stakeholders intersect or branch. We found that for the heritage nodes to be utilized as new generative value and as the new planning and design instrument for the revival and regeneration of cities in a sustainable way, they must be perceived from the network perspective, thus influencing the urban environment. Besides having the leading figure in each of the cases of the heritage adaptive reuse, in order for each node to have the network impact, traditional instruments such as the regulative role of planning and protection measures, are still essential for preserving heritage qualities and giving additional value to both the heritage and the urban context. Added values sparked the creation of strong bonds between new projects, the local community and a spatial impact as new livable places which started to act as new local centers, since residents attached the sense of place and gave new meanings to the place.

2. Materials and Methods

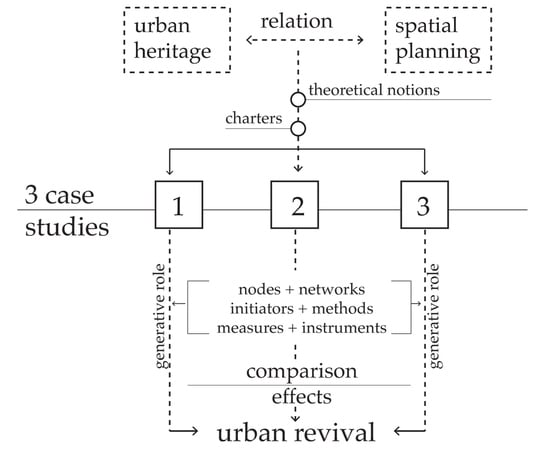

The methodology used in this paper has a multi-disciplinary character since it searches for the answers in the field of urban (re) development, strategic planning and urban management—all of which directly relate to the topic of urban heritage, forming an outline and theoretical framework of the research.

The content analysis method has been used in several stages of the research and was different in relation to the type of documentation (plans, literature, documents, photo documentation, projects) in order to enable systematization of the key elements of the analysis.

The conceptual framework of the research has been developed as the literature review, following the most important heritage conventions and recommendations in relation to strategic planning. The focal points of those documents were applied as striving points for successful, yet creative usage of urban heritage. Hence, creative usage of urban heritage has been more broadly explored and analyzed in case studies trough elements of place, program, tradition (patterns, new and old usage), networking (with other heritage nodes and actors), key agents who initiated the project, stakeholders (from public, private and civil sector), types of adaptive reuse and instruments for the operationalization of collective and individual ideas in projects. Instruments and measures were analyzed following the Vedung’s classification of regulative, economic and informational types of policy instruments [

11].

Vedung explains that “regulations are measures undertaken by governmental units to influence people by means of…rules and directives…to act in accordance with what is ordered.... Economic instruments involve either the handing out or the taking away of material resources…. Information…covers attempts at influencing people through the transfer of knowledge, the communication of reasoned argument, and persuasion” [

11] (p. 51). The main difference between the regulatory, economic and informational instruments is, according to Vedung [

11] in the following. The informational instruments tend to influence people through the communication of reasoned argument and persuasion, that economic instruments tend to build up their self-oriented interest in conforming through the financial or in-kind incentives, and that regulatory instruments tend to force them to comply by means of formulated rules and directives. In order to trace how adaptive reuse has been initiated and implemented in all three case studies, and in relation to Vedung’s threefold classification, analysis of regulative, economic, and informational types of policy and planning instruments has been conducted in our research.

The generative role of urban heritage was investigated by case study method. The advantage of the case study as a qualitative method of research is, as Flyvbjerg states, “that it can ‘close in’ on real-life situations and test views directly in relation to phenomena as they unfold in practice” [

22] (p. 235). This proximity to the reality of the case study as a qualitative method does not mean it is less strict than the quantitative method, which uses a structured questionnaire across a large sample of cases: on the contrary, it may affect the results because the quantitative researcher does not get as close to those under study as does the case-study researcher (ibid. 236). The case study method proved appropriate for this type of research as it was focused on describing the historical development paths of the city of Kikinda including the urban matrix, specific urban heritage nodes and processes of how and by whom creative ideas have been brought to light in projects. The key research methods employed for the case study were a review of primary and secondary sources (plans, strategies, reports of creative industries, as well as the written material on this topic), site investigations (four field visits) and interviews with key persons involved in projects. A total of four in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with the director of Public Enterprise Kikinda, initiator and director of the Terra Panonica, academic sculptor and director of the Terra—Center for Fine and Applied Arts, director of the Kikinda National Museum in order to gather primary data, and with the community members who shared local narratives about intangible heritage. The cases were selected to reflect how various spatially distributed urban heritage nodes and projects have been creatively used and the extent of their impact for the revival of the city. On the other hand, review of primary and secondary sources has been used to understand the policy framework which enabled those changes to occur, while the interviews and site visits provided specific insights for individual projects and allowed in-depth analyses.

Besides considering specific instruments in particular projects, it was of equal importance to assess the array of economic, social, environmental and spatial effects in the adaptive reuse of heritage as drivers of urban revival and city redevelopment. The ordinal scale analysis was applied to track those effects in the analyzed cases and to draw conclusions about the possibilities and limitations of adaptive reuse of heritage that can be reexamined in other similar situations in other cities.

3. Results

3.1. Regenerative Reuse of Urban Heritage in Relation to Spatial Planning

Alongside new movements in planning and development, the approach to the heritage protection and its integration into the contemporary life of cities has changed too, referring to, and becoming often interwoven with the planning issues.

On the European level, The European Urban Charter [

23] stressed that urban heritage has to be integrated with the contemporary needs of cities in a collaborative way in order to integrally treat different aspects of sustainability, such as the economic, social and environmental aspects. Furthermore, in the Manifesto for a New Urbanity: European Urban Charter II [

24], urban heritage is considered as an irreplaceable element of the urban fabric, essential for the city’s identity. Precisely this aspect is the main reason for the guiding principle for heritage to be considered as a crucial element in planning and thus become integrated into contemporary urban life. Particularly for the interest of this research, the Charter highlights that the factories and machines from the industrialization period are often a neglected part of urban heritage. Seen in that light, the adaptive reuse of old, industrial buildings and urban heritage can often be a sound economic solution, using innovative mechanisms and partnerships, and thus leading to the successful urban economic regeneration. Moreover, regeneration seen in that way, can as an effect, promote employment, increase the attractiveness of a city for tourists, residents and the business sector.

Similarly, on the global level, the emphasis has been moving towards the integration of historic urban areas together with protection and planning for the local development, with the idea that this approach would help maintain urban identity. Thus, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) specified in the Nairobi Recommendations [

25] that urban heritage should be integrated and adapted to social contemporary life and development. Another key point of the Nairobi Recommendations is that a number of planning instruments for the regeneration of the traditional urban areas for the new development would engage a wide range of stakeholders from the public sector, community-based organizations, experts and citizens. Furthermore, the Washington Charter [

26] adds the main principles that urban heritage should be an integral part of coherent economic and social development policies and urban planning at every level, including urban patterns, the relationship between the urban areas and their surroundings coupled with green and open spaces. Involvement and the participation of residents are further encouraged as they are essential for the success of both conservation programs and future urban development. The Xi’an Declaration [

27] pointed the need to develop planning tools and practices to manage heritage structures, sites and areas which goes beyond the physical and visual features. Meanwhile, it includes interaction with the social practices, customs, traditional knowledge activities and other forms of intangible cultural heritage aspects which defines a dynamic cultural, social and economic context. Above all, the relationship between tangible and intangible heritage on the one hand, and the social and cultural mechanisms of the spirit of the place to give meaning and value to the cultural heritage on the other hand, was established in the Québec Declaration [

28]. Lack of legal protection of the spirit of the place, especially its intangible components, raised issues that safeguarding could be best done through sharing the spirit of the place by interactive communication of people and by the concerned communities’ participation. In the meantime, the Vienna Memorandum [

29] defined the historic urban landscape as ensembles of any group of buildings, structures and open spaces, requiring new approaches for urban conservation and planned territorial development which goes beyond traditional terms of historic centers to include the broader territorial and landscape context. For this reason, UNESCO’s Recommendations on the Historic Urban Landscape [

30] were given in order to support the active protection of urban heritage and its integration into the local sustainable development processes and urban planning strategies that would help maintain urban identity in the context of structurally changed global conditions of market liberalization, mass tourism, heritage exploitation and climate change. Specifically, the approach in the Recommendations calls for the application of a range of traditional and innovative tools adapted to local contexts, such as civic engagement tools, knowledge and planning tools, regulatory and legislative measures and financial tools. Finally, the Burra Charter [

31] defined adaptive re-use as the adaptation of a place which may involve additions to the place, the introduction of new services, or new compatible usage, acceptable only with minimal impact on the cultural significance of the place.

All of the abovementioned charters and recommendations, besides the traditional protection of urban heritage, highlight the importance of integration of the program and space of the traditional and contemporary forms of urban life, urban forms and adaptive re-use of the heritage. Additionally, almost all conventions emphasize the need for interconnections and active engagement of various actors and especially civil society, as well as the need to develop new methods, planning tools and instruments, both for the heritage protection and planning of the city development.

However, there are critical issues related to the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings and sustainable development. Bullen and Love [

16] suggest that even though it has been widely recognized that the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings brings many sustainable benefits, it does create many problems. They suggest that the preservation of heritage buildings, from the economical aspect is often perceived “as being ‘investment sinkholes’ with issues associated with social and environmental sustainability being ignored” [

16] (p. 411). Moreover, the financial incentives in the form of tax concessions, and legislation that reduces building code and planning requirements, are not usually available for developers [

32], making reuse projects less viable due to high costs of technical renovations. From the environmental aspect, although there is research that the adaptive reuse projects contribute to the energy efficiency and energy savings, other observations indicate that the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings may not meet the standards set by the new buildings [

16]. Drawing conclusions from these arguments, we build our understanding of the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings in a way that it has to be measured against gains in producing generative spatial, environmental, social and economic value.

The abovementioned changes and shifts in the protection, adaptive reuse and integration of heritage related to urban planning, affect the urban development in a specific way. Confronted with the process of allocation of industrial activities from cities and growth of third service sector, decision-makers turned to the arts and culture as one of the possible strategies, because it is believed that culture can increase the sense of vitality in the economic and social sphere [

33]. Nevertheless, processes of globalization and cities competitiveness lead to increased serial reproduction of cultural attractions and commodification of the cultural tourism product [

34]. As a result, cities and regions are searching for solutions to this problem in a variety of strategies which seek to accomplish uniqueness, add value, and animate the tourist and cultural products (ibid.). In the contemporary world, it is not enough to possess cultural heritage; rather, it is necessary to transform it into experiences for consumers, both for local citizens and potential tourists. In the last quarter of the 20th century, a significant number of cities have used the benefits of cultural innovation and urban regeneration in the process of achieving these values, while at the same time, promoting the city as a good place to live and attract visitors, investments and international companies [

4,

12]. However, development of cultural tourism at heritage sites involves negotiations of various interests, the cooperation of different stakeholders and potentials regarding the heritage as a resource and its possible reuse [

35]. At the same time, urbanization and the growing public concern for the environmental quality present limits for traditional planning techniques.

3.2. Case Study

3.2.1. Historical and Contemporary Context for Cultural Revival in Kikinda

The city of Kikinda sits far from the main roads with a peripheral position both in Serbia and the Banat region. As Ilijašev explains, Kikinda is a city that can be passed by, but a city that you have to visit [

36]. On the strategic side, the borderline position is of great importance for European Integration and the development of the Euro region Danube–Krish–Muresh–Tisa (DKMT). The cooperation in the Euro region is based on economic and political joint projects, infrastructure improvements, environmental protection, development of tourism and establishing and fostering cooperation in fields of science, culture, health and recreation [

37]. Kikinda can significantly contribute to the international borderline cooperation due to its geographical location (since it is in the center of DKMT Euro region), historic circumstances, diverse demographic structure and rich cultural heritage. The spatial plan of Kikinda defines priorities in the field of tourism and emphasizes the potentials for cultural manifestation tourism which can use potentials of rich cultural–historical-ethnological heritage, ethno architecture, industrial heritage and traditional manifestations.

In order to understand these potentials, we have to take a closer look at the history of city development in Kikinda. Kikinda was a planned city, established in the eighteenth century during the time of Maria Theresa. The city was not significantly inhabited before the Second World War migrations happened, with the population ranging from 20,000 inhabitants at the beginning of the 20th century and up to 40,000 in the middle of the 20th century. An orthogonal matrix with long and straight streets dates back to the 19th century. The first General Master Plan was developed in 1970 and was followed by the “Study of architectural values of Kikinda” conducted by architect Kanački [

36]. This study initiated activities and measures for preservation, adaptation and improvement of architectural heritage. Finally, in 2003, the Government of the Republic of Serbia decided to approve the establishment of the Spatial Cultural-Historical Unit of the city center of Kikinda [

38]. This ordinance states that this Unit has origin from the years between 1750 and 1754 when the city center was built around a sizeable oval pond with a small mound in the middle where the Church was built. Preserved spatial organization and parceling were established before 1814, which was recorded in 1893, while the urban structure consists of buildings built in the period between the establishment of Kikinda and today.

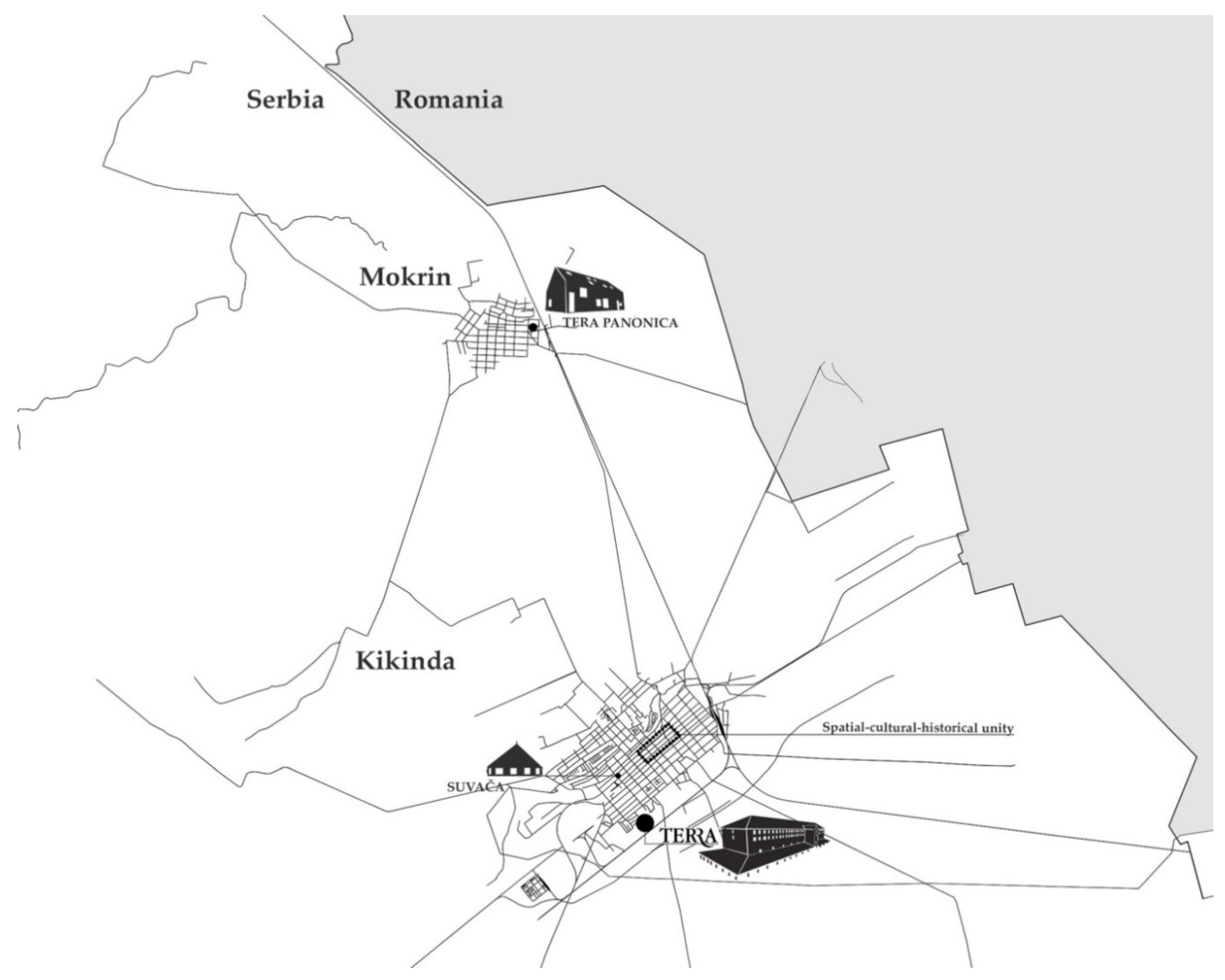

Nevertheless, most of the buildings with high architectural values have been built in the second half of the 19th century and the years before the First World War. Despite everything mentioned, Kikinda, along with its surrounding, has not yet gained a decent reputation. A well-planned city with more than 270 years old tradition, but with an important strategic position in DKMT Euro region and with precisely defined goals in all strategic documents for heritage protection and cultural tourism development, Kikinda presents an ideal study area for exploring the role between sustainable use of heritage urbanism and planning, management and design instruments. Three central nodes were selected: (1) Terra Panonica, a modern cultural and touristic center, located in the rural setting, (2) Terra—Center for Fine and Applied Arts, located on the city edge and (3) Suvača—the horse-powered mill located on the edge of the historically preserved and protected area of the city (

Figure 1).

3.2.2. Terra Panonica

Terra Panonica (

Figure 2) is a modern cultural and touristic center for the creative industries built in 2010 and is located in Mokrin village, near Kikinda. This center was built on the grounds of a former traditional rural residential estate with vernacular architecture established in early 1925. The idea for the reconstruction came from a successful local businessman who was also the investor [

39]. Through the process of internal competition, design proposal of young architectural studio “Authors” was selected. As Alfirović and Simonović explained, the design of the center relies on traditional construction, but at the same time represents a modern interpretation of authentic rural objects [

40]. Besides the fact that the center was envisioned to function as a complex of buildings, it has received numerous awards in the field of architecture and gained great public attention even after the construction of just one building. The Terra Panonica center gained the attention of the local population since it promoted active participation through workshops from the conceptual phase of the project. Greater attention was gained both because of modern design and the specific urban program which focuses on science, visual arts, music, performance, new media, social science, industrial design and architecture [

41]. Primary services offered in these facilities are the production of training and seminars, the organization of events, concerts, exhibitions, team buildings, closed events, field trips, wine degustation and accommodation. Terra Panonica distinguishes itself from the other cultural and touristic centers trough five key facts emphasized by the project leader: (1) positive isolation; (2) visitors have a chance to focus just on each other; (3) the quality matching the paid price; (4) locally grown food; and, (5) specific location that provides visitors the opportunity to get back in touch with nature; secluded but yet well connected with the region [

42].

During and after the construction process, numerous meetings of the Terra Panonica management team with the Mokrin local administration were held in order to provide active participation and to explore possibilities of citizen’s involvement. The main goal of these participatory meetings was to link traditional knowledge and contemporary creativity, while the opportunity to connect the village with the world has been recognized by the local community. As a result of the ideas acquired in that particular way, Terra Panonica uses locally grown food and promotes craftwork. One of the pilot workshops was organized with the idea of bringing together traditional crafts with modern design and illustrations, such as when sweater pillows and techniques of hand embroidery, knitting and crochet were produced by local women [

43]. Consequently, these programs empower and socially integrate women from rural areas through the development of creative entrepreneurship. Terra Panonica’s manager explains that Terra Panonica possesses a cargo bicycle–mobile souvenir shop used for the presentation of workshops crafts as a result of the cooperation with the local community [

44], which additionally promotes environmentally sustainable modes of transport on the local level. Although Terra Panonica is deeply interconnected with the location in which it operates, all actions are aimed at establishing a new type of institution that will permanently support the affirmation of young, talented and creative people and projects without the support of the state and international funds. Those ideas and the impact on the community is demonstrated through the organization of various events in Terra Panonica, such as the international student camp for photographers, colonies for applied ceramics, textile clothing recycling seminars and workshops for making wooden mosaics from scrap materials [

39]. The other type of products promotion and distribution is planned to be implemented through the web site, such as selling items online. Ideas and products include for example handmade goat milk soap, famous Mokrin leaf cheese, etc., in order to promote local manufacturers, authentic and traditional products from the region, as well as the production of souvenirs suitable for home production that can increase the economic and social inclusion of the local community and foster their identity. Equally important, all the events and regular programs of the Terra Panonica are either free or with a reduced price for residents, both from the village of Mokrin and the city of Kikinda. Additionally, the management team acquired a farm located 400 meters from the project site where the locally grown and organic food is produced. Additionally, not officially declared as such, the farm contributes to the eco village characteristics of the Terra Panonica and to the spatial impact of this case onto the urban fabric. One more environmental aspect of this case is the use of vented facade and roof system panels which considerably reduced heating and air conditioning costs, thus preserving energy resources and contributing to efficient energy use [

45].

Based on what is perceived as adaptive reuse in spatial and architectural terms, Terra Panonica reused existing rural agricultural plot, preserving and reconstructing one of the existing houses, while designing new ones on the foundations of original buildings. New buildings were designed in a contemporary manner using materials, such as glass and aluminum, while respecting the traditional shape and volume. From a symbolic perspective, the main focus was on the preservation and promotion of craftsmanship as intangible heritage, and using the historical element of the spatial organization of typical rural estate for the Banat region from the beginning of the 20th century.

3.2.3. Terra—Center for Fine and Applied Arts

Terra—Center for Fine and Applied Arts (

Figure 3) is located on the urban edge of Kikinda in the former tile factory built in early 1895. This factory has more than 145 years old tradition [

36], but due to the process of modernization, these industrial facilities were abandoned in the mid-1980s. Due to the visionary ideas of Terra founder and sculptor, the accessibility of clay resources on the location, existence of an almost ideal working place, and with the support of industry of construction materials of baked clay—Toza Marković and the Municipality of Kikinda, Terra—Center for Fine and Applied Arts was officially established in these facilities [

46]. Several reconstructions and refurbishments were necessary, and they have been conducted according to the plan of detailed regulation. The project was supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Serbia, Provincial Secretariat for Culture and the Municipality of Kikinda. The most important reconstruction was completed in 2010 when modern Terra atelier was established. Since then, atelier presents a unique working space for artists from around the region and from all over the world. The atelier is mainly used for the International Symposium of Sculptors because of its modern equipment and the tallest sculpture baking oven in Europe with a height of 2.5 m. Under those circumstances, the Symposium is unique in the world in terms of the large format sculpture in clay and contemporary art. At the end of the symposium, every artist leaves behind one sculpture of a large-scale format and two small-scale format sculptures to be exhibited in the courtyard of the atelier. Besides that, during the rest of the year, the atelier is also used for pupil’s summer camps, multimedia weekends and humanitarian workshops. Apart from hosting applied and fine arts, Terra organizes music concerts of young and still not affirmed musicians in the atelier and the courtyard. Traditional manifestation Modern Acoustic Music Festival—Terra Acustica was established, which marks the end of the Symposium [

43].

Besides the atelier, Terra—Center for Fine and Applied Arts owns the Terra gallery in the city center [

47], and the new Terra Museum was opened at the end of 2017. The Terra Museum has been built according to the plan of detailed regulation for the area of former military facilities. Sculptures are exhibited in the old factory yard, local parks, the Municipality building and in the city square. Over the years, Terra has fostered cultural and educational networks as an important cultural heritage node. Notably, Terra established a deeper connection with cross border institutions from Romania and realized projects such as Inclusive art [

48], strengthened up existing connections with Museum of Vojvodina and Museum of Contemporary Art of Vojvodina, established new connection with Romanian universities of Art, and finally, supported national educative architecture and urban design projects with the Faculty of Architecture from Belgrade [

49]. Over time, the Terra Center has received significant financial support from NIS (Petroleum Industry of Serbia). The founders and managers of Terra center have many other ideas about fostering Terra’s educational role for the community through the establishment of Master studies, sculpting courses for different groups of tourists and molds manufacture for serial production of clay sculptures by local citizens [

46] that have not yet been realized yet [

50]. The founder of Terra is convinced that opening a new Terra Museum in 2017 realized according to the plan of detailed regulation, established 3 kilometers northeast and annual symposiums can help in the process of creating a Terra brand [

50]. The established network of the Terra—Center for Fine and Applied Arts and new Terra Museum, already created substantial social impact on the community and spatial impact on the city in general, acting as a new generative layer.

Terra presents the case in which adaptive reuse is applied to the old factory and military facilities in the outskirts of the city. From the spatial and architectural perspective, significant changes in interior design have been realized with traditional materials using recycled brick, contributing to the environmental aspect and followed by the activation of belonging outdoor space for public use with exhibited clay sculptures. Adaptation of the clay facilities and production technology is perceived as a central symbolic element for the continuation of clay tradition through contemporary art. The historical element consists of the retained spatial layout of former factory buildings, with preserved original timber structural elements, roof clay tiles and brick facades in the case of the atelier building and the sheltered clay sculptures drying space.

3.2.4. Suvača—The Horse-Powered Mill

Suvača in Kikinda (

Figure 4), Serbia, is one of the two remaining horse-powered dry mills in entire Europe. It was built in 1899, but the mill stopped working in 1945 and in 1951 it was declared as the Cultural Monument and categorized as the immovable cultural property of exceptional significance in 1990 [

51]. Back in the day, Suvača was a mill that used the horse power as its driving force for grinding grain. The mill had three main parts: the drive space, the mill space, and the miller’s chambers. The drive space was and still is a unique one because of its pyramidal roof where the device that had run the millstone was located in [

52]. Suvača had always been a symbol of tradition and culture in the city of Kikinda and Vojvodina region, besides being the part of the material cultural heritage, it preserves the intangible cultural heritage: traditional values, old way of life and the economy, traditional building techniques, the way of processing grain, the mill craft and different beliefs about the witches whom protected it from possible theft and damage [

43]. Suvača was an important part of social life and its social value was enormous until the mill stopped working in 1945.

Suvača is a facility of outstanding cultural significance which was put on the list of preferential interventions in 2013, within “Ljubljana Process II Rehabilitation of Our Common Heritage” project conducted by the Council of Europe [

53]. The European Commission and the Ministry of Culture and Information of the Republic of Serbia provided about 80,000 € for the renovation of Suvača with the idea to transform it into a community center to enable local entrepreneurship related to the intangible cultural heritage of local culinary and flour products (ibid.). The technical measures for the preservation were taken during the mill renovation to make it accessible and open to all citizens of Kikinda. Meanwhile, the recognition of the Mill’s importance on the EU level prompted the additional interest of the local community with the participatory planning workshops, which were used to obtain ideas and suggestions about possible future uses for its revival. Some of them came to fruition as part of different city events in Kikinda. Consequently, the reopening of Suvača was marked by the event ‘At Suvača, at 5 p.m.’, where women from the ‘Suvača’ association, dressed in the traditional outfits, prepared customary meals made of flour and pumpkin that the whole region is famous for. During the event, dedicated to cereals and grain products, various workshops were held for the elementary pupils, with around 300 visitors. Furthermore, the National Museum of Kikinda organizes the summer event, Days of Suvača, with a series of educational workshops in which women association from the surrounding villages promotes their local traditional characteristics and gastronomy. Additionally, as a local community initiative, the first ‘Suvača music festival’ was organized by local musicians in front of the mill in 2016 [

43]. For the rest of the year, Suvača provides only sightseeing tours for tourists with a professional guide explaining historical facts with no additional or interactive programs. Further promotion of Suvača as a tourist attraction and improvement of local plans and use of IPA cross border funds with Hungary, that have been acquired but still not utilized, could represent a model for the preservation of traditional values and further revival of the site.

Adaptive reuse of the old horse-powered mill for touristic and cultural purposes, supported by the restoration of unique interior elements of timber structure and use of traditional and original materials of roof clay tiles, enabled the continuation of the original use of flour production in a contemporary manner. From a symbolic standpoint, Suvača presents evidence of a lifestyle and identity of the Banat region grounded both on the tangible aspects of the outstanding cultural significance of the horse-powered dry mill, as well as an intangible aspect of preserved original processes for occasional grain grinding. Adaptive reuse of Suvača included additional new usages of educational workshops for food preparation, which are complementary to the original functional layout and architectural space.

4. Discussion

Generally speaking, for heritage to fully utilize its cultural and historical potential in the modern globalizing world, it must find the balance between contemporary and traditional, both for place and program. Having that in mind, Terra Panonica incorporated traditional rural housing spatial layout into modern architectural design, while regarding the program, it balances between the contemporary and the traditional—providing new and attractive concepts for tourists and businesses, yet respecting local culture, music, food, products. Nevertheless, Terra balances with contemporary and traditional, both in program and place. It introduces contemporary design in the interior of the traditional industrial and military facilities, produces contemporary art using the traditional technique of clay sculpturing and in contemporary manner interprets exhibition space by taking it out from galleries to the open public space, parks and, possibly one day, to individual households. Equally important, for Suvača to reach its potentials that go beyond being solely heritage building, it has to open up more to community initiatives, such as the ones previously described. It has to provide additional facilities and allow contemporary design, since it is located outside of the protected Spatial Cultural Historical Unit, contributing thus to the economic and social community and therefore urban development.

Above all, for the nodes of heritage to be utilized as the new generative value and as the new governance, planning and design instrument for the revival and regeneration of cities, they have to be perceived from the network perspective.

Figure 5 provides a graphic illustration of the complexity of the network of heritage nodes with various cases developed over the time, considering not only other urban heritage nodes, but visitors, businesses, local producers and associations, artist, cultural and educational institutions. The circumstances of projects initiation and the existence of a leading figure, either from the private or public sector, does appear to have the incremental significance for the network range, as well as spatial, social and economic impacts during implementation. Thus, Terra, as a public institution is one that has the most apparent network connections with public, private and civil sector. Although perceived and developed as a private initiative, Terra Panonica has also developed a strong network and social bonds with the local community and businesses. Even though Suvača has a high heritage significance among three analyzed cases, it is yet to find relevant institutions and audience for reaching its full potential.

Regarding planning instruments for the implementation, we can identify ones that have proven successful for the cases we have analyzed. Having that in mind, the regulative role of detailed regulatory plans, design competitions, and protection measures are, although traditional tools, still essential for preserving heritage qualities and giving them additional values. While analyzing economic instruments, economic self-sustainability is quite essential for private initiatives, while public ones need to allocate additional financial and logistic resources as a subsidy especially for traditionally not so economically feasible activity such as culture. Those resources are even more available and diverse in cross border areas. Establishing connections with the local community are of equal importance, both through the promotion of social entrepreneurship or by using locally grown products. Branding stands as an additional layer for the successful node integration into the network, positioning urban heritage not only on local, but also on a national and global level. Informational instruments are the most apparent through the active participation of local residents, thus bringing legitimacy and promoting cultural heritage. Establishing links with international agencies and active web promotion builds the informational base for the successful revival and regeneration of the cities.

Moreover, besides considering, individual or combined, regulatory, economic and informational planning instruments, used in particular cases for the adaptive use of heritage as generators of urban revival and city redevelopment, it is of equal importance to consider the effects those projects have from economic, social, environmental and spatial aspects of sustainability. This research has shown that for the heritage nodes to be utilized as the new generative value for the new planning and as a design instrument for the revival and regeneration of cities, it has to be perceived from the network perspective, thus influencing the urban environment in a sustainable way. Therefore, the following important economic, social and environmental effects are presented in

Figure 6.

From the economic perspective, research reveals that all three projects have economic responsible leadership in supporting local associations, local producers while two projects only use cross border funds (Terra, Suvača). The additional significant economic effect that is going to become even more evident in the future is the increase of the land value of the particular site and the surrounding area.

As researched, most of the effects are focused on the social aspect of sustainability. Having that in mind, the network of those nodes that were initiated by individuals from the local area is even more important for the vitality of small and medium-sized cities. The other group of social effects is concentrated on the art, creativity, culture, and education that enable the preservation of traditional values. Additionally, these effects increase the extent of the liveliness of the area around heritage nodes while contributing to the decrease of migration of youth from medium and small towns in Serbia. Richness in social benefits is interconnected with the variety of economic effects that position individual nodes in the network, acquire acceptance from the local community and enable the continuation of the creative usage of urban heritage.

Environmental effects go in line with the recycling, regeneration of the land, reuse of existing buildings and raising awareness on the already built land that would in other case be abandoned as a brownfield site. It is apparent that more attention is yet to be devoted to environmental sustainability in terms of the use of renewable energy sources and energy efficiency, both in reconstructed and new buildings.

Regarding spatial effects, adaptive reuse of individual buildings changed the character of previous industrial or rural plots that only recently started to have an implication on the surrounding area as well, as presented in examples of Terra Panonica’s newly acquired farm and Terra’s recently established Museum.

Given these points, in order for heritage nodes to be utilized as the new generative value for the revival of cities, they have to be interconnected, while achieving a balance among all aspects of sustainability. As researched, indicators of success of the adaptive reuse of heritage for urban revival range from the 40% for Suvača case, 73% for Terra case and 74% for the Terra Pannonica case.

5. Conclusions

Activating cultural heritage in a creative manner, as shown in this research, is of great significance both for the continuity of tangible and intangible heritage and for the regenerative urban development. As Swensen and Stenbro [

54] underline, the activation of historical contexts can best be perceived as a precondition to ensure the future of cultural heritage in dynamic urban contexts.

Heritage urbanism, practiced in this way as the process of activating heritage nodes, utilized as the new generative value for the revival and regeneration of cities, is starting to be considered amongst Kikinda’s public officials, entrepreneurs, residents, tourists and experts because of the economic, social, environmental and spatial benefits that these regenerative projects have for the local community, the place itself and the broader surrounding environment and context.

We found that for the heritage nodes to be utilized as the new generative value and as the new planning and design instrument for the revival and regeneration of cities, they have to be perceived from the network perspective. From the network perspective, the adaptive reuse of heritage nodes has to influence the urban environment and have a spatial, social and economic impact, strong bonds with the local community and connections with other heritage nodes and actors.

We concluded from our analysis that even when all stakeholders are not involved in the early phases of the participatory planning processes prior to the adaptive reuse, their later active involvement during the projects’ lifespan contributes to the legitimacy of the process and the sustainability of the solutions. This approach has been enabled thanks to the social and economic corporate responsibility of key people who initiated the projects.

From the spatial perspective, if the network between heritage nodes and urban fabric is missing, then they will remain isolated zones, disconnected from the surrounding area.

We define our findings based on the

heritage urbanism model in which Locke et al. [

15] (p. 12) defined urban heritage as an infrastructure and a public good for community’s benefits. In the model, they quest for adaptability and generativity of cultural heritage rather than preservation, conservation and authenticity alone, as is often the case in the heritage management.

Furthermore, we found that besides the leading figure in each case for the network impact, traditional instruments like the regulative role of planning and protection measures are still essential to preserve heritage qualities and give both them and urban context the additional values.

This practice shows that successful cases of heritage reactivation and reuse in a contemporary manner, which respects both the tangible and intangible value of the particular compounds, buildings and artifacts, and at the same time contribute to the sustainable urban development by using different planning instruments, does not have to produce conflict between heritage protection and planning. On the contrary, as Bajić Brković states: “Planning has to be concerned of the specific features protection calls for, while on the other side the protection ought to understand the ratio planning relies on” [

14] (p. 491).

Thus, building on these notions and the research we have presented here, by perceiving heritage use in relation to the notions of strategic planning, we can draw two general theoretical remarks on how they can learn from each other.

On the one hand, the field of heritage protection can learn from the strategic planning on how to use different planning instruments to incorporate various actors’ interests in the integration of heritage in line with the contemporary community’s needs and the common good. It can also benefit from the insights and tools of strategic planning, especially on the combination of and the integration of different economic, social and environmental instruments and aspects of sustainability for the creation of the comprehensive visions of development.

On the other hand, strategic planning can learn from the heritage protection and activation on how to adaptively reuse heritage nodes acts as the new generative value and as new governance, planning and design instrument for the revival and regeneration of cities in a twofold way. First, it generates new meaning that heritage has for the people and the communities. The second is for the activation of both tangible and intangible heritage as a generative force. Simultaneously, they foster the spirit of the place and give additional value to the heritage, while maintaining urban identity, historic character and significance.

The questions of the planning approach and concepts to the heritage management, activation, adaptability, revival and generativity which are underlined in this paper undeniably have methodological implications. In light of this statement, further development regarding the very method of work, planning process, technique and criteria to be applied would be of great significance.

Future research directions that would be of significance and which would have a methodological and practical challenge for the heritage nodes and urban development, as researched here in the network perspective, might go in a twofold way. One would be to assess how to establish links and relations of the generative heritage nodes and their surrounding in the urban revival with usually, protected city cores. The other would be to evaluate the implications in what way those relations could be beneficial from the perspective of all three main aspects of the sustainability. Relations with the surrounding areas are meant not only to be established physically, but from the economic, social and environmental aspects as well as becoming generator of urban revival.

The generative role of the adaptive reuse of cultural heritage, defined here as nodes in the network perspective for urban revival, as well as our set of classification of sustainable effects, can become relevant for similar situations in other small and medium-sized cities. However, the methodology presented here must be tailored to each particular situation and context within its own specific heritage significance, actors and location assets.