Abstract

This study proposed a dual-pathway model consisting of a supply-driven pathway and a demand-driven pathway to explain the green value endorsement process. The supply-driven pathway embodies a business’ espoused value of global environmental value through value integration, which leads to the endorsement of green value. The demand-driven pathway is the consumer’s identified value that reflects the consumers’ specific environmental value process to form green value endorsement. The study conducted a research survey on 623 customers who had experience with purchasing environmentally friendly products in Taiwan. The empirical study model used was structural equation modeling. The main path indicated that the consumer’s identified value positively affected the value-bridging frames, which mainly positively affected the endorsement of green values. Our study indicated that the demand-driven pathway played the main role in forming the green value endorsement. Green enterprises tend to merely emphasize their own business’ espoused values. This study is the first to examine a dual pathway in the green value endorsement process and considered both the supply-driven and demand-driven pathways in green value endorsement, which marks new ground in taking into account the value interpretive frames and value-bridging frames of value integration in the extant literature, providing a highly effective and useful profile for green marketing.

1. Introduction

Many green enterprises have contributed to the emerging green society, as they can produce more green products than non-green products. When green enterprises grow, they attract more enterprises to follow and join the line of green enterprises through green marketing. Regular enterprises are encouraged to transform into green enterprises and mitigate environmental pollution issues [1]. The price of green products is higher than that of non-green products because the cost of raw materials for the former is relatively high [2]. Relative to non-green products, green products usually hold a disadvantageous position when attracting consumer purchases [3]. Therefore, we should determine how marketers of green enterprises attract their target consumers to accept the business’ espoused value of the green enterprise, how to make the target consumers endorse the environmental value [4,5] and how to enhance the loyalty behaviors of the target consumers [6,7], which all make for a challenging campaign in green marketing [8]. If green marketing works, it can be deemed as a potential window of opportunity in achieving a win–win solution between green enterprises and environmental sustainability [9,10].

Green marketing proposes environmental values to attain the value endorsement of the target customers [11]. When green enterprises declare their environmental values, marketers need to attract target consumers to purchase these green products, which is where the value endorsement model becomes useful [12]. This study presents an extended green value endorsement model that can be considered as green value endorsement obtained in the green marketing process. Therefore, green marketers need to integrate the consumer value and global value espoused by these enterprises. Green enterprises weigh these two types of environmental values to obtain the value endorsement of the target consumers; that is, when enterprises launch their green products, they need to establish how green marketers can effectively meet the unmet demands of consumers and communicate the enterprises’ environmental values to win the consumers’ value endorsements [4,13].

The relevant literature on consumer loyalty refers to the loyal purchase of the tangible products and intangible services of enterprises, and related variables are perceived quality, perceived satisfaction, and perceived value, among others [14,15]. The green value endorsement of this study is similar to that of loyalty marketing, but it specifically refers to the endorsement behavior on the intangible environmental value of the enterprise, rather than the loyalty behavior on the tangible green products of enterprises. Green value endorsement means that consumers agree with the environmental value and then recommend via word-of-mouth behavior [16]. For example, the Suntory Group provides a wide range of non-alcoholic beverages and health goods and espouses their environmental values to obtain a green value endorsement from customers.

In the past, consumers did not easily understand the concept of enterprise due to limited information. However, as a result of the popularity of mobile phones and the Internet today, consumers can easily obtain the enterprise value. Consumers are trained to be meticulous and to examine things more closely, and therefore will be concerned with the business’ espoused values, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) and environmental values. That is, as consumer awareness increases, more consumers will care about the enterprise’s values rather than the quality of their products; therefore, the level of value endorsement is higher than that of loyalty. As this aspect of the literature is relatively limited [15,17,18], the current study can fill this gap in the literature.

This study defined green value endorsement as a group of consumers that are eager to express shared values and have the drive to participate with collective goals [12,19]. These consumers have specific values and present a well-developed value identity as distinguishers [20]. Value endorsement represents loyalty marketing and commitment management among marketing practitioners [8,21]. Therefore, marketing scholars have become more interested in better understanding the causes and effects of value endorsement [12,19,22,23,24]. However, the underlying mechanisms that demonstrate the value integration process in the green value endorsement and social integration of target customers remain unclear.

The traditional marketing literature emphasizes a single pathway of value endorsement process; that is, a business’ espoused value promotes green endorsement through value interpretive frames that lead to social integration, which are the main outcomes of marketing [20,25]. Therefore, green enterprises actively enhance the environmental value of enterprises and seek the value integration mechanism of value interpretive frames to create the green value endorsement of innovators and early users [16]. Given these developments, the authors argue that the prevailing tactics to investigate green value endorsement can be improved by a dual pathway method. This model has two pathways.

The first is the supply-driven pathway, which begins with the business’ espoused value of the green enterprise. The value is created when green enterprises declare the environmental value as their shared vision or philosophy [26]. To mitigate climate change, to save Mother Earth, and to save energy, among others, are common declarations, which have led to these enterprises’ value interpretive frames to obtain the green value endorsement [27]. For example, creating harmony with people and nature, growing for the good of the Earth, and giving back to society are the espoused values of the Suntory Group. This value is usually set by the founder or chief executive officer of green enterprises. The content mostly has a universal value, which can attract personnel, but not consumers. This pathway is called the firm’s environmental value-driven pathway as it is initiated by the green beliefs of green enterprises [28,29].

The second is the demand-driven pathway, which begins with the consumer’s identified value of green enterprises. The consumer’s identified value is created when green enterprises find similarities and differences in the environmental values between enterprises and customers and expand specific environmental values to meet the target customers’ expectations and to align with green enterprises [30]. Homeland security, reliable supply, efficient tools, oil cost saving, and low health risk, among others, are common declarations of consumer’s identified values, and these declarations have mainly led to value-bridging frames to obtain green value endorsements. For example, using clean water in production, responsible production using organic materials, health and well-being to a secure homeland, and climate action to lower health risk are the consumers’ identified values of the Suntory Group. The consumer’s identified value is normally formulated by green enterprises and is obtained from the important environmental values of consumers to meet the unmet demands of target consumers. It contains the self-interest of the consumers’ concern and can more easily attract consumers. This pathway is called the consumer’s environmental value-driven pathway, as it is initiated by the value cognitions of the enterprise and consumers [31,32]. The content of the value interpretive frames and the value-bridging frames is considered to be a value integration mechanism in the value endorsement process. Therefore, one of the objectives of this study was to provide insights into the dual pathway perspective to create the green value endorsement of early users and an early majority.

Most drivers of green value endorsements have been documented in the value integration literature, but an integrated and systematic understanding of the business’ espoused values to form value integration to further facilitate the development of green value endorsement literature is lacking [16,20,25,33]. This study introduces two types of value interaction, namely value interpretive frames and value-bridging frames, to represent the communication and value gap management mechanisms as mediators for the dual-pathway model consisting of the supply-driven and demand-driven pathways [19,22]. The supply-driven pathway explains the value interpretive frames. The value interpretive frame indicates that enterprises change the standing points and consideration facets when communicating their recognition and appreciation of the environmental value to consumers [27]. The value interpretive frame is formed from the change in the consumer perception of sub-cultural embeddedness and a specific main culture [20]. The demand-driven pathway explains the value-bridging frames. A value-bridging frame is created when enterprises make an effort to fill the gap between the two parties to reduce the value conflict and hostility caused by the value difference [34]. The value-bridging frame is formed from an enlarging explanation scope, a higher value goal, and value innovation alternative tools to bridge the value difference [35]. For example, the Suntory Group uses advertisements, storytelling activities, CSR reports and a website, links to a special website from the QR code, links to related new digital contents (e.g., Facebook, Line and Twitter), and face-to-face interaction, among others, to organize its value integration activities.

In sum, this study aimed to expand the existing knowledge on how target customers become involved in green value endorsement from value integration and how the value integration process affects green value endorsement. This study contributes to the green value endorsement literature by proposing a dual-pathway model that includes the supply-driven and demand-driven pathways. This study identified the obvious drivers of green value endorsement by integrating and expanding the established theoretical frameworks and drew on organization culture theory [36], a discourse analytic viewpoint [37], and persuasion theory [38] to develop the antecedent mechanisms for the supply-driven pathway to affect the customers’ value interpretive frames. We introduced a multidimensional construct of the demand-driven pathway based on social identity theory [39], social cognitive theory [40], and social presence theory [41] to influence consumers’ value-bridging frames in the green value endorsement process. Furthermore, we derived the value interpretive frames and value-bridging frames within value integration. We begin by discussing the green value endorsement mechanisms of Grogaard and Colman [20] in the current single mediator of value integration in the green value endorsement model to expand the two mediators in the value integration processes related to the value interpretive frames and value-bridging frames, thus enhancing the knowledge of the causes and effects of the two types of value integration processes in the green value endorsement literature [14].

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 is the literature review and hypothesis development. Section 3 details the research methodology and research design. Section 4 presents the empirical results. Section 5 summarizes our conclusions, suggests related recommendations, and provides future research directions.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

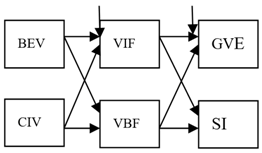

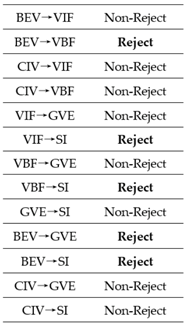

Currently, in the marketing field, green enterprises that promote their espoused values are recognized by target customers through green marketing [42,43]. The values are usually based on global environmental values of the enterprises’ missions and visions [20]. However, this global environmental value may not satisfy the unmet demands of target consumers [28]. Nevertheless, it must meet the unmet needs of target consumers and fill their specific environmental values (i.e., particular environmental value-in-use) to achieve the goal of green marketing [44]. Therefore, green enterprises educate target consumers with specific environmental values to meet the individual environmental needs through green marketing activities, and generate specific environmental values to attract consumers that identify with and endorse those values [2,45]. An obvious perceived value-in-use exists to enforce the green value endorsement of the enterprises, which is the main content of the green marketing activities of green enterprises [46]. This concept is the central idea of the expanded green value endorsement model in this study. Figure 1 shows the extended green value endorsement model.

Figure 1.

The research framework of the extend value endorsement model.

2.1. A Business’ Espoused Values Begin the Supply-Driven Pathway

A business’ espoused value is the starting point that shapes logical inference and is used by the marketing field to promote an enterprise’s values and achieve the strategic and operating objectives of an enterprise [27]. A business’ espoused values should answer the question ‘Who are we?’ and highlight the environmental values of the enterprise. Simons [26] defines business’ espoused values as those that can illustrate mission statements, vision statements, and codes of conduct, which usually comprise the belief systems and boundary systems of corporations. The belief systems within this structure include the values, purposes, and directions held by green enterprises, and the boundary systems include formal rules, prescriptions, and proscriptions linked to environmental threats [29,44]. Therefore, applying organizational culture theory and exploring the business’ espoused values enable the realization of the basic underlying assumptions and shared artifacts, barriers, and opportunities for the value management initiatives [28,36].

The value interpretive frames refer to the standing points and consideration facets that green enterprises emphasize to communicate the value of corporate self-identification when faced with the target consumers [31]. Value interpretive frames act like a mirror that can translate their espoused values to a concrete appeal [20]. Based on social cognitive theory [40], which indicates that individuals’ cognition can drive their attitude and sound behavior, value interpretive frames are cognitive elements that form a discourse analytic viewpoint, reducing context-free inference [37]. Value interpretive frames help individuals understand what they represent. The interpretive frame on its own employs the idea of projecting problems and related solutions using specific underlying concepts in a certain situation [27,47]. This frame is an interpretation of the value’s meaning, presenting a certain reference structure in the communication process [31].

Green enterprises focus on an environmental value when firms have a clearly espoused value [28,48]. Accordingly, green enterprises have become more aware of their espoused values. In value awareness, green enterprises perceive the central idea to have a universal green and sustainable environmental value and an integrated value that defines the value proposition of the founder [20]. Green enterprises emphasize the universality of the espoused values, as it can be applied to the whole world and not only their hometown. These enterprises can communicate the global value to surpass regional differences. Therefore, green enterprises execute the appropriate value translation within their own cognitive thinking [27] and explain the desired environment and lifestyle. Green enterprises can highlight the desired situation of target consumers and describe a visionary situation and cultural characteristics [32]. That is, enterprises can interpret and translate values to surpass sub-cultural embeddedness and the perceptions of a specific main culture [49]. Therefore, they form their own green communication to promote benign value interpretive frames to the target consumers [1]. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1.

A business’ espoused value positively and causally influences the value interpretive frames.

Furthermore, value-bridging frames mean that enterprises complete their efforts to communicate and span the environmental value gap between enterprises and consumers to reduce the value gap and hostility caused by different values, as green marketers need to bridge the gap and address consumers’ emotional needs [50]. With sufficient value cognition sensitivity, green enterprises can employ the value similarity between enterprises and consumers and work to ‘reserve the [similarities] and keep the differences’ through their own cultural compatibility [51]. This cultural compatibility of an organization can encompass differences in environmental values between the two parties, resulting in value flexibility and preparatory work toward the foundation of value recognition, since the flexibility of customization is to understand and find opportunities to build consensus [32].

The main idea of value-bridging frames in green enterprises is whether marketers can cut into the gap of the environmental value of the target consumers and join together to reduce or even avoid misunderstandings caused by cognitive mistakes [35,52]. Therefore, green enterprises can apply their espoused values (including global environmental values and integrating environmental values) to promote marketing concepts to target consumers (to exchange views and clarify ideas) and construct effective value integration through useful value-bridging frames [34]. That is, green enterprises can employ value-bridging frames with higher goals by proposing themselves at a desired level, can broaden the scope of interpretation to bridge their values by considering the differences between desired and current environmental values, and can bridge the value gap by brainstorming more creative solutions [35]. By clarifying the value focus of customers, it is easy to create a win–win scenario and develop new knowledge within the value conflicts to create new opportunities for problem solving [50]. Value gap management practices can reduce the conflict and hostility caused by the value gap, fill the value gap between the targeted and existed values, and then complete the environmental value-bridging frames [50]. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2.

A business’ espoused value positively and causally influences the value-bridging frames.

2.2. A Consumer’s Identified Value Begins the Demand-Driven Pathway

A consumer’s identified value is an acknowledgment or recognition of similarities and differences in value between green enterprises and target consumers, and refers to meaning perception and responsive feelings toward a value [30]. Meaning perception and responsive feelings include the task of associating tangible and intangible values. A consumer’s identified value attempts to construct an overall meaning of value in the mindset of others, leads to a solid value proposition, and creates an expected response of acceptance [30,42].

The consumer’s identified value, which is parallel to brand identification in marketing, recognizes the consumers’ salient value and finds similarities and/or differences in the consumers’ value performance imagery from the cognition process of marketers [53,54]. The difference between a consumer’s identified value and a business’ espoused value is that the former includes value cognition and difference clearance between green enterprises and target consumers, whereas the latter is clearly oriented toward the goals of enterprises. This explanation of the procedure infers that a consumer’s identified value reveals useful insights into value interpretive frames, as the consumer’s identified value can focus on a particular need and then improve the understanding of social identity theory [31]. Additionally, the consumer’s identified value is another type of organizational culture that influences decision-making and purchasing behaviour, and expresses explicit knowledge aside from personal and unspoken tacit knowledge [36]. Therefore, the consumer’s identified value can promote value integration to explain preference reversal and decision biases.

Under an appropriate framework, green enterprises can discover the consumers’ own salient value by detecting the value characteristics of the consumers, and they can discover the performance imagery content by detecting the outstanding performances of the consumers [55]. Green enterprises can realize the consumers’ environmental values, current actions, what other people are doing now, and their reasons for holding certain values [56]. Marketers can understand why target customers think the way they do, can stimulate internal inference, strategic thinking, and external behavior of the target customers, and can adjust their inner attitude to communicate with target customers by establishing value interpreting frames [57]. Specifically, green enterprises can examine the points of parity, the points of differences, and the points of contention between green enterprises and target consumers to apply the consumer’s identified value [54]. Therefore, green enterprises suppress self-thinking and change the perspective, positioning themselves on the counterside [30]. Marketers adjust the value standpoints and employ certain reference structures to empathize with other peoples’ roles and behaviors.

Therefore, marketers can push aside self-centered thinking and their own self-reference criterion to identify why consumers think the way they do [58]. Green enterprises explain the standpoint and the thinking focus of the target customers through sub-cultural embeddedness, and they strengthen the main culture behind consumer thinking through the perception of the specific main culture [20]. Green enterprises understand the consumers’ thoughts by understanding their culture, lifestyle, and values, and they create sound value interpretive frames in accordance with the consumers’ understanding [27]. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 3.

A consumer’s identified value positively and causally influences the value interpretive frames.

Moreover, green enterprises construct proper value-bridging frames by extending consumer values. Self-adjusting the inner attitudes to see the full view of a situation is possible by identifying the rationale of consumer values. Marketers can launch value-bridging procedures by adjusting our minds to achieve a higher vision. Then, green enterprises are no longer self-exclusive, excluding others from joining, or narcissistic in disregarding the existence of other individuals [34]. Green enterprises can set up a higher green goal to resolve the environmental value gap between enterprises and consumers through a global vision via the attitude to meet updates and changes [35]; they can also broaden the scope of the interpretation of environmental values to consider the differences between global and local environmental values. Additionally, they can propose new green alternatives through creative thinking. These treatments can cross the environmental value gap between enterprises and consumers and achieve value-bridging frames through an integrating perspective [59]. Marketers then become cross-cultural translators and develop value-bridging frames using consumers’ identified values [31]. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 4.

Hypothesis 4.

A consumer’s identified value positively and causally influences the value-bridging frames.

2.3. Value Interpretive Frames and Value-Bridging Frames

In this section, we discuss the verification stage of the green value endorsement, the function of which can be conveyed by employing interpretive frames and value-bridging frames. Frey and Cruz-Cruz [60] argued that green value endorsement tasks usually lead to the discovery and translation of core value commitments, and that value interpretive frames and value-bridging frames can yield discovery stages and translation stages, respectively. Therefore, we employed value interpretive frames and value-bridging frames to handle the endorsement process and explored the interrelationship between them. Proper administrative assignments in the cognitive training of communication for the value endorsement process can effectively provide communication benefits and meet the green enterprise value [32]. Sound communication and value gap management mechanisms can be beneficial catalysts of the integration process [27]. Value interpretive frames have the potential to play an important role in advanced value-bridging frames because an abundance of empathetic content can effectively resolve the potential hostility instead of facing the differences in business’ espoused values directly [61]. Therefore, the value interpretive frames directly influence the value-bridging frames because the former are formed using the green marketing vision, and the value-bridging frames can be applied by value gap management [59].

At the beginning of realizing the value interpretive frames, green enterprises can conduct a dialogue to understand the value of the target consumers, dissolve the prioritized value gap, reach a value consensus that is mutually beneficial, and eliminate inappropriate and improper values [62]. Therefore, green enterprises explore the target consumers’ position and priorities based on the sub-cultural embeddedness in the main culture as well as the main culture behind the environmental values of the target customers through the perception of the specific main culture. They partake in cognitive learning from each other to dissolve the value gap through an interactive decision process between enterprises and consumers [63]. Therefore, the value-bridging frames are created. Hypothesis 5 embodies this idea.

Hypothesis 5.

Value interpretive frames positively and causally influence the value-bridging frames.

2.4. Green Value Endorsement and Social Integration

The achievement of the green value endorsement is the final part of our framework. The green value endorsement indicates that the targeted value has been identified and that an atmosphere of the shared values, expressed as ‘value of unity’ and ‘we are one’, has been created [16]. The achievement of green value endorsement includes social integration. The green value endorsement is an environmental value that has been recognized by consumers and has created an atmosphere of green shared values to produce an environmental value resonance, that is, ‘we are one’ [64,65]. It refers to the identity of the environmental value and the willingness or expectation of the product or service of the target consumers, which comes from the idea of consumers based on the ability of the benevolent, trustworthy, and green environmental performance of the green enterprise [24,66].

When green enterprises apply value interpretive frames, they actively seek an empathetic viewpoint between enterprises and consumers through the embedded sub-culture among the target consumers and the perceived specific main culture of the target consumers; that is, the green enterprises actively find similarities between enterprises and consumers to build consistency in consumers’ standpoints [59]. Value interpretive frames can accommodate or neglect the form differences between enterprises and consumers and produce an acculturation effect that infiltrates their lives. The acculturation effect can further incite changes in original lifestyles by ‘immigrating into customs’ [67]. It produces a lifestyle adaptation effect and makes a green trust of the different values, efforts, and priorities, thus forming green value endorsement [45]. This means that green value endorsement requires target consumers to recognize the environmental value and creates an atmosphere surrounding the commonly shared value. This shared value becomes a critical success factor for green enterprises [18]. Moreover, this endorsed value is used to differentiate consumers to form environmental value segmentation and becomes a key strength of green enterprises, resulting in a clear competitive advantage to generate green loyalty [68]. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 6.

Hypothesis 6.

Value interpretive frames positively and causally influence the green value endorsement.

In terms of value-bridging frames, green enterprises can bridge the environmental value gap between enterprises and consumers and form a positive green attitude in target consumers [35]. That is, green enterprises can lead target consumers to accept, identify, and even internalize the established green attitude to reach a value consensus [63].

When the target consumers accept and agree with the green shared value, environmental value resonance occurs; that is, the target consumers are willing to share a certain green shared value with the green enterprises and are glad to share the same identity [11]. Then, the target consumers show that ‘we are one’ and that we are all green organizational units, thus establishing the green value endorsement [16]. Furthermore, when the target consumers have internalized the green shared value (e.g., the value as distinguishers), they are happy to tell others about this green shared value, which is different to the values of other enterprises [64]. Therefore, the target consumers are willing to enjoy the green value endorsement and consider the identity important.

Green enterprises can attract the target consumers’ endorsement through a clear understanding of each other’s values [35]. Then, green enterprises create a higher goal and a broader scope of green development to accommodate these values. Furthermore, green enterprises establish a tacit cooperative understanding to create additional explanations and available resources to reach a value consensus or value consistency between the enterprises and consumers through the value-bridging frames [37]. For example, green marketers add more of their budget and efforts toward solving this dilemma. This action leads to the process of cognitive reaction between the enterprises and consumers, resulting in attitude changes at certain levels [57]. Green enterprises create a variety of value gap management mechanisms, build new solutions for creative implication, and produce the effects of the value-bridging frames.

Note that green marketers can strengthen the value compatibility between green enterprises and consumers through value-bridging frames. Different values can be merged to create a new value, resulting in a short-term assimilation effect [69]. That is, the original value elements change and merge into other similar elements, thus forming new value elements that can even produce a long-term phenomenon of the enculturation effect [38]. Through the processes of enlightening, learning, and inheriting, a longitudinal transformation within the value can be achieved [11]. Therefore, the green value endorsement can be made in a subtle and imperceptible manner. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 7.

Hypothesis 7.

Value-bridging frames positively and causally influence the green value endorsement.

Social integration refers to the green value endorsement that has affected the consumers’ actions and results in loyalty awareness behaviors [65]. Social integration is the willingness of consumers to voluntarily participate in the community when faced with environmentally sustainable green activities [70]. These activities include continuing to buy green products, participating in related green-oriented activities, voluntarily recommending green practices to others so that they can join, and word-of-mouth dissemination. A harmonious relationship between the firm’s environmental value and the consumer’s environmental value can effectively enhance the function of the human–environment interaction, satisfaction, and sustained commitment to enterprises based on the social presence theory [65]. The attitude behind the green value endorsement presents a type of attachment attitude, which creates loyalty awareness among the target consumers [55]. This attitude enhances the extent of the consumers’ community awareness and promotes active participation in various green marketing activities [70,71]. Social presence theory indicates that the social presence of a medium affects the consumers’ understanding of the messages sent by the enterprises [38,72]. Based on social presence theory, we proposed hypotheses on how the integration mechanism affects the green value endorsement achievement objectives for green managers to use to maximize the effectiveness of the green value endorsement [72]. A harmonious relationship between the firm’s environmental value and the consumer’s environmental value can effectively enhance the function of the human–environment interaction, satisfaction, and sustained commitment to enterprises [65]. Recognizing green value endorsement outcomes that effectively enhance social integration is important, so managers can employ them to enhance the benefit of value change in green marketing [20,38]. They form a variety of normative actions and action imperatives to produce outcomes of social integration.

Therefore, the green value endorsement obviously affects participant behavior and even leads to future loyalty consciousness in social integration behavior [68]. The green value endorsement guides us on how to do things and to use this green shared value to evaluate related issues, thus promoting social integration [65]. A colourful social interaction connection [31], which produces green normative behavior and green action imperatives [20], is then formed. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 8.

Hypothesis 8.

Green value endorsement positively and causally influences social integration.

3. Measurement and Modeling

3.1. Measurement

Regarding questionnaire construction, businesses’ espoused values were measured using a modified scale described by Khandelwal and Mohendra [27] and Grogaard and Colman [20]. We used the two dimensions of global values and integrating values and included six questionnaire items. Amongst them, global values highlighted the universal characteristics of the values; integrating values were those that can be applied on an international basis and are not exclusive to the company. For consumers’ identified values, we considered salient value and performance imagery; six items were included in questionnaire [54]. The salient value is a prominent trait in which a consumer identifies with a particular environmental value. Performance imagery is from the cognitive interaction process of the consumer and company marketing staff. Consumers find the environmental value of the performance results from a specific image and explore similarities and/or differences in it.

For value interpretive frames, we considered sub-cultural embeddedness and perceptions of a specific main culture and included six items [20]. Amongst them, sub-cultural embeddedness was the need to understand the local context; the perceptions of a specific main culture were perceived of characteristics of the main culture. We measured the value-bridging frames using three dimensions, namely, enlarging the explanation scope, a higher value goal, and value innovation alternatives, and included nine items [35]. A company can enlarge the explanation scope of the interpretation of the value to the desired value and can take into account differences between the present and the ideal (desired) environmental value; a higher value goal is based on the company’s ideal level, constructing a value-bridging framework through higher purposes; a company can brain-storm value innovation alternatives to fill the value gap and come up with more creative solutions.

For green value endorsement, we devised two dimensions, namely, value resonance and value as distinguishers, and included six items [20,45]. Amongst them, value resonance is the shared identity of ‘we are unity’; the value as distinguishers is the value perceived from a major differentiation from other companies. Finally, we used a six-item questionnaire to elucidate the two dimensions of social integration: normative action and action imperatives [20,63]. Normative action entails that members engage in consensual decision making, and action imperatives entail that the values can shape how we do things. The six variables were measured with 39 items, and six-point Likert scale items were used. The range was from 1 to 6 (from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”). Amongst them, 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = rather disagree, 4 = rather agree, 5 = agree, and 6 = strongly agree. We employed six-point rating scales since there was no need for the middle category of our purposes (see Appendix A for the questionnaires).

Note that, as we determined the development questionnaire, our research process was considered. We organized a steering committee, which comprised a team of leaders including university professors and business managers, and then employed focus group interviews to examine and revise the questionnaire for the study for a research questionnaire with high academic and practical standards.

3.2. Modeling

The structural equation model (SEM) is one of the most important tools in behavioral science and social science research. It simultaneously integrates a measurement model (that is, exploratory factor analysis) and path analysis (that is, simultaneous equation models in econometrics) [73]. The use of SEM is commonly justified in the social sciences since it can impute relationships between unobserved constructs (latent variables) from observable variables [74].

The whole SEM (also called the linear structural relationship model, LISREL) contains two parts [73]: (1) the structural equation model, which defines a linear causal relationship between a latent exogenous variable (x) and a latent endogenous variable (h), and reveals the causal relationship between latent exogenous variables (x) and latent endogenous variables (h) as h = B h + G x + z, where B and G are vector matrix; and (2) the measurement model, which defines the measured relationship for each latent endogenous variable (h) with its constructs and for each latent exogenous variable (x) with its constructs. It highlights the relationship between the hypothetical concepts of latent variables (h, x) and the measurement variables of their manifest variables (y, x) in order to describe the relationship characteristics and assumptions between them. The relationship form is y = Ly h + e and x = Lx x + d, where e and d are the error terms, and L is the vector matrix [73]. We employed SEM based on both latent (unobservable) variables and manifest (observable) variables in the case of our study model since most of the constructs were abstractions of unobservable phenomena [75]. Thus, SEM is remarked for its flexible interplay between theory and data, bridging theoretical and empirical knowledge for a better understanding of the real world [75]. We estimate the structural equation model by using the SPSS-AMOS software.

The SEM can analyze the mutual causality between variables and covers factor analysis and path analysis [74]. It can also offset the shortcomings of factor analysis and incorporate error items without being limited by the premise conditions of path analysis (simultaneously equations). The SEM can deal with multiple correlation issues at the same time; that is, it can deal with the relationship between a series of variables at the same time, so it is obviously superior to the traditional multivariate analysis methods such as regression analysis, factor analysis, multivariate analysis of variance, and canonical correlation analysis. [76]. Factor analysis, path analysis, and regression all represent special cases of SEM [77].

In terms of reliability analysis, this study used Cronbach’s α reliability (Kuder–Richardson reliability) to analyze the internal consistency between questions. In practice, the Cronbach’s a coefficient is used to verify the internal reliability (consistency) of each construct. The test criterion had an alpha coefficient greater than 0.6, which showed sufficient internal reliability [78]. This study also calculated the composite reliability (CR) to test the reliability of each variable in the structure. The calculation formula for CR is (sum of standardized loadings)2/[(sum of standardized loadings)2 + (sum of measurement errors)]. According to [79], if the CR is greater than 0.6, the potential construct is credible and acceptable.

In terms of validity analysis, the discriminant validity in this study was confirmed by calculating the average variance extracted (AVE). If the AVE is greater than 0.4, the discriminant validity between these variables can be confirmed [79]. The calculation formula for the AVE is (squared sum of the standardized loadings)/[(squared sum of the standardized loadings) + (sum of measurement errors)]. Hair, Anderson, Tatham, and Black [80] pointed out that the CR value should be greater than 0.7 and the AVE value should be greater than 0.5, and the SEM has discriminant validity. Additionally, this study examined the construct validity through the loading values of each hypothesis construct in the SEM and whether there were two elements. The first was that the correlation coefficient was significant (p-value < 0.05); the second was R2 greater than 0.4, and the loading of all constructs was significant [77]. Thus, with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), we can support the establishment of construct validity by examining the evidence of the appropriate items for each construct that involves their respective hypothetical constructs.

3.3. Other Considerations

It is a viable option to explore consumers’ decision to buy or not using a dummy variable, with only values of 0 and 1 and to employ a Tobin model as the statistical model. However, an investigation into the purchase decisions of consumer behaviour should explore the degree of purchase intentions of the consumer. Therefore, we employed Likert multivariate scales to measure them rather than use a dummy variable.

Researchers from different scientific fields have proposed the issue of the optimal volume of response scales in various optimization criteria [81]. There are five criteria as follows: scale validity, sensitivity, ease of use, information recovery, and information processing [82]. Though some researchers have argued that there are no significant benefits in adopting more than five response scales [83,84], many researchers have favoured a higher number of response options [82,85]. Many researchers have favoured a solution with a number of scales between five to seven [82,86]. Green and Rao [85] compared scales with 2, 3, 5, and 7 response categories and suggested adopting at least five scales per variable.

There are several determinants that affect the decision making of consumers. Furthermore, consumers in different markets make different considerations. Take a car purchase for example. Low-income consumers may be concerned with the basic functional needs and prices of the car. However, for high-income market segmentation, some consumers may not only value the basic functions and price but also the energy-saving and carbon reduction effects. The environmentally conscious consumers’ concern for sustainability affects their day-to-day decision making [87]. Such consumers may be more interested in the oil–electric hybrid or the electric vehicle. Even the costs of an electric vehicle are higher, so environmentally conscious consumers are willing to buy them for the sake of environmental sustainability. Consequently, electric vehicles have the potential to enter the mainstream around the world in the near future.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The official questionnaires for our study were completed from 25 March to 15 May 2018. We dispatched 1500 paper questionnaires to respondents in Taipei City and New Taipei City. Overall, we collected 623 valid questionnaires. The effective questionnaire recovery rate was 41.5%. The demographic data were categorized by gender, age, occupation type, place of residence, and income level. This study used a structural equation model (SEM) with the full information estimation method. All the relationships between the variables, including information from potential variables, were considered, and complete information on the variables was retained. This method is superior to the traditional simultaneous equation regression model for rigorous analysis procedures [73]. According to Jackson [88], at least 10 times as many the samples are needed compared with the number of measurements used when the full information estimation method is employed. In our study, we met the requirement with 390 respondents and 39 questions in the survey. The effective number of samples in our study was 623, which exceeded the requirement set by Jackson [88].

Within the 623 samples, males occupied 44.8%, and females occupied 55.2%. We divided our samples into three different age groups, under the age of 25 years old, 26–50 years old, and above 51 years old. Under the age of 25 years old occupied 38.7%, 26–50 years old occupied 41.6%, and above 51 years old occupied 19.7%. We also divided our samples into four different education levels: high school, bachelor, master, and Ph.D. Consumers at the high school level occupied 27.0%, consumers at the bachelor level occupied 38.5%, consumers at the master level occupied 31.9%, and consumers at the Ph.D. level occupied 2.6%. We further conducted a one-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) to examine whether the sample characteristics would affect the results (value endorsement and social integration) as it can present a sample that is representative or not. We adopted age, gender, and education as the characteristics that may affect the result. The results indicate that the p-values of age, gender, and education level were insignificant in affecting value endorsement and social integration (p-value > 0.05).

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

We jointly assessed the reliability for all items of a construct by computing composite reliability (CR). The CR was computed using the following equation: (sum of standardized loading)2/[(sum of standardized loading)2 + (sum of measurement error)]. According to Fornell and Larcker [79], a CR larger than 0.6 indicates an acceptable fit of the data. Therefore, the higher the latent construct is, the more easily the latent constructs can be examined. In our samples, we obtained the following CR values: 0.848 for the business’ espoused value, 0.763 for the consumer’s identified value, 0.721 for the value interpretive frames, 0.902 for the value-bridging frames, 0.827 for the green value endorsement, and 0.842 for social integration (Table 1). We found that the CR for these samples was greater than 0.6, which means that the data exhibited an acceptable fit [75]. We also used Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to examine the internal CR of each construct. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for all the constructs of the six variables from our samples were greater than 0.6, indicating a reasonable internal consistency [77].

Table 1.

Results of reliability analysis and validity analysis.

We found that the loadings for the hypothesized factors were significant (p-value < 0.05), with the R2 being larger than 0.4, and all of the factor loadings were considered substantial (exceeding 0.4) based on the SEM. Construct validity can be supported by examining the evidence from each construct and by involving items related to their respective hypothesized components using a confirmatory factor analysis [77].

We further calculated the average variance extracted (AVE) to confirm the discriminant validity in this study. The AVE was computed using the following equation: (sum of square standardized loading)/[(sum of square standardized loading) + (sum of measurement error)]. If the AVE is larger than 0.4, then the discriminant validity between the variables will be achieved [79]. We calculated the following AVE values: 0.744 for the business’ espoused value, 0.627 for the consumer’s identified value, 0.567 for the value interpretive frames, 0.754 for the value-bridging frames, 0.708 for the green value endorsement, and 0.727 for social integration. All of the AVE values were greater than 0.4, indicating that these variables had correctly measured the meaning of measurement and held discriminant validity. Our model possessed discriminant validity in accordance with the standards set by Hair et al. [89], who declared that CR values should be greater than 0.7 and that AVE values should be greater than 0.5 (Table 1). Note that discriminant validity for the second order factors was estimated and reached by comparing the unconstrained model with the constrained model where the correlation of factors was set to 1 in the study [90]. Thus, the unconstrained model with a drop of one degree of freedom returned a chi-square value that was at least 3.84 lower than the constrained model. A two-factor solution provided a better fit to the data, and the discriminant validity between unconstrained and constrained models was supported.

4.3. Model Fit and Structural Model Results

We used multiple fitness indices to test the model’s validity and established the test indicators from multiple perspectives to interpret the model’s fitness [91] (Table 2). First, we calculated that χ2/df = 2.327, which is more accurate than the χ2 itself because χ2/df is not affected by the number of samples and is acceptable for the criteria for fitness of more than two and less than five [80]. Second, the goodness of fit index (GFI) represents the explained variance and covariance of the model [73]. Producing a higher GFI enables more variance to be explained by the study model. Our study obtained a GFI of 0.979, thereby passing the criteria of a GFI greater than 0.9. The adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) was 0.946. MacCallun and Hong [91] indicated that the GFI, AGFI, and CFI values should be above 0.8 to have a good fit. CFI and NFI represent the comparative and normal fitness of index, respectively, which are other fitness indices of the SEM. In this example, we used the CFI (0.978) and NFI (0.964) to judge the validity of the data, as these indices were above 0.9 [76]. Furthermore, we used the root mean square residual (RMSR) and root mean square error approximation (RMSEA) to fit the model with unknown, but optimally chosen, parameter values for the population covariance matrix when the parameter values were available [92]. Thus, the RMSR was 0.020 (<0.05), and the RMSEA was 0.046 (<0.08) [93]. The results of the RMSR and RMSEA scores indicated a good fit for the study model.

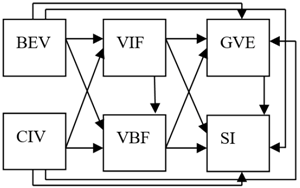

Table 2.

Empirical results of the structural equation model (SEM).

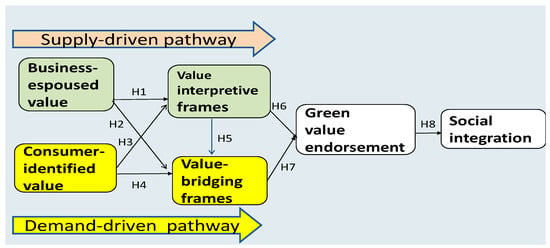

Table 2 shows the structural model with the coefficients and significant relationships between variables, indicating that almost all of the variables followed the hypothesized directions. The business’ espoused value had positive effects on both the value interpretive frames (H1:β1 = 0.246, t-value = 2.428) and the value-bridging frames (H2:β2 = 0.071, t-value = 1.139). The consumer’s identified value also had positive effects on both the value interpretive frames (H3:β3 = 0.788, t-value = 6.285) and the value-bridging frames (H4:β4 = 0.658, t-value = 5.791). The value interpretive frames had positive effects on both the value-bridging frames (H5:β5 = 0.186, t-value = 3.381) and the green value endorsement (H6:β6 = 0.167, t-value = 3.384). The value-bridging frames had a positive effect on the green value endorsement (H7:β7 = 0.586, t-value = 8.847). Finally, the green value endorsement had a positive effect on social integration (H8:β8 = 0.959, t-value = 15.280).

4.4. Rival Model Analysis

Bagozzi and Yi [77] demonstrated the necessity of a rival model and suggested using the difference in the χ2 value to compare and test the validity of the rival model [94]. Hu and Bentler [95] used the values of GFI, CFI, RMSEA, and related indices for path coefficients to compare and analyze the models. Hu and Bentler [95] argued that the significant ratio is a critical decision rule for comparing the study model and the rival model.

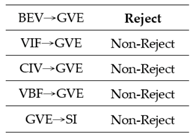

Table 3 shows our rival model analysis. The first rival model identified the different types of causal relationships among the related variables. Based on a regular structural school framework, the second rival model identified the direct effects of the business’ espoused value, the consumer’s identified value, the green value endorsement, and social integration without mediators [96]. Based on the management system school, the third rival model identified whether or not causality between the green value endorsement and social integration was actually present [97].

Table 3.

Rival model comparison.

The significant ratio of the study model (87%, with seven of eight significant paths) was greater than that of Rival Models 1 (70%), 2 (80%), and 3 (57%). The values of CFI, GFI, AGFI, RMSEA, and RMSR for the study model (Table 2) were all superior to those for the three rival models (Table 3). Thus, we found that the study model was more accurate than the three rival models [98].

5. Conclusions and Discussion

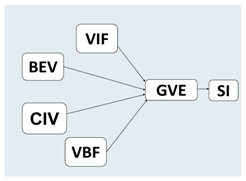

We built a dual-pathway model to expand the findings of the existing single pathway-based studies in terms of explaining the green value endorsement process. This study marks a new ground in examining the customers’ green value endorsement from the theoretical perspectives of the supply-driven pathway and the demand-driven pathway. Our research found two major causal relationship pathways. The first pathway shows that the consumer’s identified value largely positively influences the value-bridging frames and that the value-bridging frames positively influence the green value endorsement and social integration. The second pathway indicates that the business’ espoused value positively influences the value interpretive frames and that the value interpretive frames positively influence the green value endorsement. Therefore, the demand-driven pathway plays a main role in forming the consumers’ green value endorsement. The consumer’s identified value (0.3856) was proven to be more effective than the business’ espoused value (0.0679). That is, the consumer’s identified value is used to develop a social identity that is superior to that of the business’ espoused value, which is goal-oriented from a well-developed organizational culture. Therefore, our results agree with social identity theory [39,99].

We hope that, with this research, a consumer’s identified value strategy, by collecting and analyzing potential customer demand, can be designed to create value integration for green marketing and to provide customized value-bridging frames designed for green marketing. To meet marketing expectations and to satisfy customers and owners, green enterprises have to implement value-bridging frames through the consumer’s identified value [100]. The value-bridging frames had significant positive causal relationships with the green value endorsement in our model. This outcome indicates that marketers can provide compatible, integrated, and attractive environmental values to customers when green marketing has the power to instill value integration [52]. When enterprises develop their organizational knowledge and apply it through value integration, green marketing can provide more possibilities for green value endorsement [16]. Applying these strategies makes consumers feel satisfied about the customized services and motivated to be environmentally conscious [64]. Green enterprises tend to merely emphasize their own business’ espoused value. In fact, enterprises should strengthen the consumer’s identified value to help obtain the value endorsement of consumers.

Our academic contribution extends the study of Grogaard and Colman [20], which asserts that the business’ espoused value positively influences value endorsement and social integration through the value interpretive frames. We created a new channel called ‘from the consumer’s identified value to the value-bridging frames’, which we extracted from the value gap management mechanism and extended to the business’ espoused value to influence the value interpretive frames. This treatment provides new insights into the green value endorsement.

The managerial implication of our study is that the consumer’s identified value is the critical green marketing strategy necessary to obtain green value endorsement through value-bridging frames. By beginning with the consumer’s identified value, customers felt positive, relaxed, and receptive to the cognition of the individual, rational, and emotional needs arising from the unmet demand, thus making them more likely to purchase green products that they might not have considered otherwise [56]. For example, when consumers encounter specific messages, such as the slogans ‘living with water’ and ‘we value the blessing of water’ from the Suntory Group, consumers’ hearts are more likely to be touched, and a green value endorsement is more likely to materialize [66]. The consumer’s identified value, their value-bridging frames, and green value endorsement increase when customers support a specific environmental value.

This finding in our extended green value endorsement model can assist green marketing managers in influencing consumers to reach their value using the value gap management mechanisms to explore effective green marketing strategies [72]. Green marketing managers can employ these strategies to build green management practices that shape social integration behavior. When consumers participate in green marketing activities, they pay more attention to the environmental impact and social fusion of the society than to the product, price, and promotional atmosphere of the store [1]. For example, the Suntory Group engages with the local community by fostering collective actions to solve water issues and to enrich the society. The enterprise launched a ‘natural water sanctuary’ project at Maker’s Mark Lake in the United States to support water conservation activities in 2016. As the one-time promotion of green products does not change consumers’ environmental values [10], the consumer’s identified value can enhance the extent of the social integration behavior through the social presence process [10,38].

There are some limitations to this study. First, the surveys were conducted in Taiwan. However, Taiwanese consumers may not represent all green consumers in all countries. Second, because of budget and time restrictions, only 623 questionnaires were collected. It is most likely that the bias can be more effectively decreased through more questionnaires. Third, the survey focused on a single customer perspective. Since the green business personnel/salesperson and marketing executives directly contact the shoppers, they can recognize the consumers’ needs. The inclusion of producers or businesses in the survey for future research is recommended. Common method variance is the fourth research limitation. Podsakoff and Organ [101] indicated that common method variance when self-reported surveys are employed as a measurement tool is a potential issue in behavioural study. The respondents rated their perception of the predictor variable and criterion variable, and the exogenous variables and endogenous variables were collected from the same rate or source [102]. We produced a temporal separation by introducing a cover picture and short story between the independent variable and dependent variable to create a time lag to ensure that the measurement of the independent variable was not directly connected to the dependent variable [102]. However, our research design (temporal separation) may not have adequately handled the issue of common method variance by decreasing the perceived relevance of previously recalled information in short-term memory. Hopefully, this can be improved in future efforts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.-Y.C. and C.-J.H.; methodology and formal analysis: T.-Y.C.; investigation and resources: C.-J.H.; writing—original draft preparation: T.-Y.C.; writing—review and editing: C.-J.H. and T.-Y.C.

Funding

This research was funded by the Academic Top-Notch Project (three years project) Funding Sponsorship of National Taipei University, Taiwan (R.O.C), grant number 106-NTPU_A-H-162-002 and 107-NTPU_A-H- 162-002.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank National Taipei University for budget supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaires.

Table A1.

Questionnaires.

| Measurements | Questionnaires |

|---|---|

| Business’ espoused value | |

| global values |

|

| integrating values |

|

| Consumer’s identified value | |

| value salience |

|

| performance imagery |

|

| Value interpretive frames | |

| sub-culture embeddedness |

|

| perceptions of the specific main culture |

|

| Value-bridging frames | |

| higher value goal |

|

| value extended explanation |

|

| value innovation alternatives |

|

| Green value endorsement | |

| Value resonance |

|

| value as distinguishers |

|

| Social integration | |

| normative action |

|

| action imperatives |

|

References

- Papadas, K.K.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Carrigan, M. Green marketing orientation: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, Y.S.; Park, K.D. Assessing the effects of perceived value and satisfaction on customer loyalty: A ‘green’ perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Naylor, R.W.; Irwin, J.R.; Raghunathan, R. The sustainability liability: Potential negative effects of ethicality on product preference. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.I.; Lin, S.R. The effect of green marketing strategy on business performance: A study of organic farms in taiwan. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. 2016, 27, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, S.M.; Chew Kun, L.; Phaik Nie, C. Green purchase intention of laundry detergent powder in presence of eco-friendly brand. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2017, 9, 128–143. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart, A.; Naderer, G. Quantitative and qualitative insights into consumers’ sustainable purchasing behaviour: A segmentation approach based on motives and heuristic cues. J. Mark. Manag. 2017, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Brough, A.; Wilkie, J.E.B.; Ma, J.; Isaac, M.; Gal, D. Is eco-friendly unmanly? The green-feminine stereotype and its effect on sustainable consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebelhausen, M.; Chun, H.H.; Cronin, J.J.; Hult, G.T.M. Adjusting the warm-glow thermostat: How incentivizing participation in voluntary green programs moderates their impact on service satisfaction. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 80, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.J.; Tan, K.H.; Geng, Y. Market demand, green product innovation, and firm performance: Evidence from vietnam motorcycle industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pujari, D. Mainstreaming green product innovation: Why and how companies integrate environmental sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.; Robinson, S.; Poor, M. The efficacy of green package cues for mainstream versus niche brands how mainstream green brands can suffer at the shelf. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.S. A study on consumers’ attitude towards brand image, athletes’ endorsement, and purchase intention. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2015, 8, 233–253. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibanez, V. Desert or rain standardisation of green advertising versus adaptation to the target audience’s natural environment. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 917–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.Y.; Tsai, H.T. A dual pathway model of consumer loyalty in brand community settings: Intrinsic need fulfillment and extrinsic cost perception. J. Manag. 2016, 33, 559–585. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S. Towards green loyalty: Driving from green perceived value, green satisfaction, and green trust. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 21, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogerlioglu-Demir, K.; Tansuhaj, P.; Cote, J.; Akpinar, E. Value integration effects on evaluations of retro brands. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 77, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The big idea: Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S. The drivers of green brand equity: Green brand image, green satisfaction, and green trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeppen, J.; Jamal, A. Collaborating for success: Managerial perspectives on co-branding strategies in the fashion industry. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 30, 925–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogaard, B.; Colman, H.L. Interpretive frames as the organization’s “mirror”: From espoused values to social integration in mnes. Manag. Int. Rev. 2016, 56, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.B.; Krishna, A.; McFerran, B. Turning off the lights: Consumers’ environmental efforts depend on visible efforts of firms. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A. Positive adolescent career development: The role of intrinsic and extrinsic work values. Career Dev. Q. 2010, 58, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H. Compulsive buying: A growing concern? An examination of gender, age, and endorsement of materialistic values as predictors. Br. J. Psychol. 2005, 96, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, J.; Kamakura, W.A. The economic worth of celebrity endorsers—An event study analysis. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.; Holt, S.; Frow, P. Relationship value management: Exploring the integration of employee, customer and shareholder value and enterprise performance models. J. Mark. Manag. 2001, 17, 785–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R. Levers of Control: How Managers Use Innovative Control Systems to Drive Strategic Renewal; Harvard Enterprise Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal, K.A.; Mohendra, N. Espoused organizational values, vision, and corporate social responsibility: Does it matter to organizational members? J. Decis. Mak. 2010, 35, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, D.W. Organizational cultural theory and research administration knowledge management. J. Res. Adm. 2017, 48, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, B.; Naughton, M. The expression of espoused humanizing values in organizational practice: A conceptual framework and case study. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.S.T.; Li, W.K. Extreme values identification in regression using a peaks-over-threshold approach. J. Appl. Stat. 2015, 42, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.C.; Slotegraaf, R.J.; Chandukala, S.R. Green claims and message frames: How green new products change brand attitude. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.; Kirk-Brown, A.; Cooper, B.K. Does congruence between espoused and enacted organizational values predict affective commitment in australian organizations? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Man. 2012, 23, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiden, B.K.; Price, A.D.F. The effect of integration on project delivery team effectiveness. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2011, 29, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, T.Y.; Chuang, C.M. Creating shared value through implementing green practices for star hotels. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 678–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.B.; Parboteeah, K.P. Multinational Management: A Strategic Approach, 6th ed.; Thomson Learning, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E. Organizational Culture and Leadership; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen, K. Questions as interactional resource in team decision making. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2018, 55, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, S.M.; Saunders, C.S. The social construction of meaning: An alternative perspective on information sharing. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzel, S.; Halliday, S.V. The chain of effects from reputation and brand personality congruence to brand loyalty: The role of brand identification. J. Target Meas. Anal. Mark. 2010, 18, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior, 2nd ed.; Nelson-Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Reinartz, W. Creating enduring customer value. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 36–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, E.K.; Kleinaltenkamp, M.; Wilson, H.N. How business customers judge solutions: Solution quality and value in use. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 96–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, F.; Kindstrom, D.; Kowalkowski, C.; Rehme, J. The risks of providing services differential risk effects of the service-development strategies of customisation, bundling, and range. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 390–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailova, S.; Minbaeva, D.B. Organizational values and knowledge sharing in multinational corporations: The danisco case. Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 21, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E.; Hakanen, T. Value co-creation in solution networks. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero, L.W.; Heath, R.G. Generational perspectives in the workplace: Interpreting the discourses that constitute women’s struggle to balance work and life. J. Bus. Commun. 2012, 49, 332–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanoff, B.; Daly, J. Espoused values of organisations. Aust. J. Manag. 2002, 27, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsetsos, K.; Chater, N.; Usher, M. Salience driven value integration explains decision biases and preference reversal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 9659–9664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidan, M.; Dorfman, P.W.; de Luque, M.S.; House, R.J. In the eye of the beholder: Cross cultural lessons in leadership from project globe. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2006, 20, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, C.; Piekkari, R. Crossing language boundaries: Qualitative interviewing in international business. Manag. Int. Rev. 2006, 46, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Singh, R.; Sharma, S. Emergence of green marketing strategies and sustainable development in india. J. Commer. Manag. Thought 2016, 7, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, I.; Martínez, E.; de Chernatony, L. The influence of brand equity on consumer responses. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Narus, J.A.; Van Rossum, W. Customer value propositions in business markets. Harv. Bus Rev. 2006, 84, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bickart, B.A.; Ruth, J.A. Green eco-seals and advertising persuasion. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, B.Z. Another look at the impact of personal and organizational values congruency. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, O.; Beechler, S.; Taylor, S.; Boyacigiller, N.A. What we talk about when we talk about ‘global mindset’: Managerial cognition in multinational corporations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 231–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratbekova-Touron, M. From an ethnocentric to a geocentric approach to ihrm: The case of a french multinational company. Cross. Cult. Manag. 2008, 15, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, B.J.; Soule, C.A.A. Green demarketing in advertisements: Comparing “buy green” and “buy less” appeals in product and institutional advertising contexts. J. Advert. 2016, 45, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, W.J.; Cruz-Cruz, J.A. Value integration: From educational computer games to academic communities. IEEE Technol. Soc. Manag. 2013, 32, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Durif, F.; Arcand, M. An analysis of the origins of collaborative consumption and its implications for marketing. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2017, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, K.R.; Christiansen, T.; Gill, J.D. The impact of social influence and role expectations on shopping center patronage intentions. J. Acad. Mark. 1996, 24, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorderhaven, N.; Harzing, A.W. Knowledge-sharing and social interaction within mnes. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 719–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, S.; Chartrand, T.L.; Fitzsimons, G.J. When brands reflect our ideal world: The values and brand preferences of consumers who support versus reject society’s dominant ideology. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 42, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaume, Y.R.F.; Brodbeck, F.C.; Riketta, M. Surface- and deep-level dissimilarity effects on social integration and individual effectiveness related outcomes in work groups: A meta-analytic integration. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 85, 80–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, A.; Bhattacharya, S. The market value of celebrity endorsement evidence from india reveals factors that can influence stock-market returns. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Morgan, N.A. “Greening” the marketing mix: Do firms do it and does it pay off? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Goyal, T. Social influence and green marketing: An exploratory study on indian consumers. J. Custom. Behav. 2013, 12, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkman, I.; Stahl, G.; Vaara, E. Cultural differences and capability transfer in cross-border acquisitions: The mediating roles of capability complementarity, absorptive capacity, and social integration. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Muñoz, P. Entering conscious consumer markets: Toward a new generation of sustainability strategies. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2017, 59, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.M.; Hsu, M.H. Understanding the determinants of users’ subjective well-being in social networking sites: An integration of social capital theory and social presence theory. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2016, 35, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. Lisrel 8: Structural Equation Modeling with Simplis Command Language; Scientific Software International, Inc.: Mooresville, Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-60623-876-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R.H. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 0-8039-5318-673. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structure equations models. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 76–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A.; Long, J.S. Testing Structural Equation Model; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Analyze Multivariate of Data; Sant’Anna, A.S., Neto, A.C., Eds.; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Alwin, D.F. Feeling thermometers versus 7-point scales: Which are better? Sociol. Methods Res. 1997, 25, 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, E.P. The optimal number of response alternatives for a scale: A review. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, G.D.; Taber, T.D. A Monte Carlo study of factors affecting three indices of composite scale reliability. J. Appl. Psychol. 1977, 62, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Converse, J.M.; McDonnell, C.J.; Presser, S. Survey Questions: Handcrafting the Standardized Questionnaire; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Green, P.E.; Rao, V.R. Rating scales and information recovery: How many scales and response categories to use? J. Mark. 1970, 34, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]