Same Same but Different: How and Why Banks Approach Sustainability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- What types of sustainability strategies do banks implement?

- (2)

- What prevailing motives stimulate these different types of strategies?

2. Theoretical Background

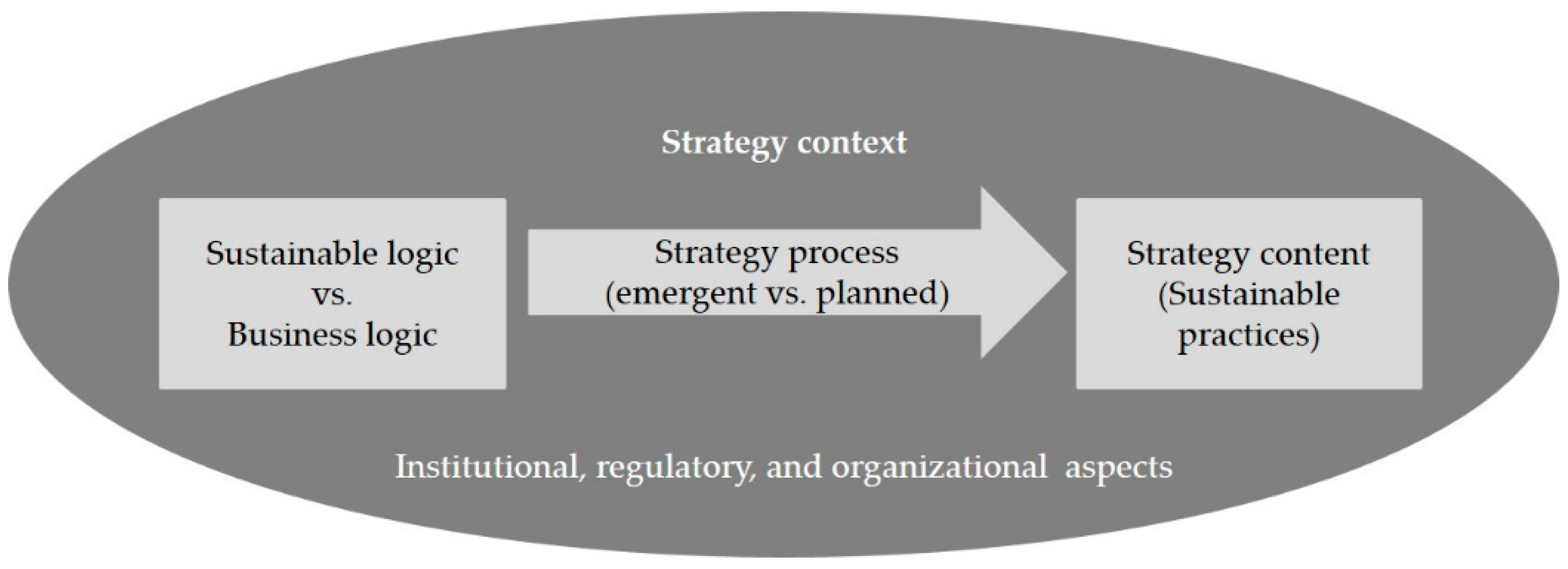

2.1. Sustainability Strategies

2.2. Corporate Motives for Sustainability

2.3. Sustainability in the Banking Industry

3. Methods

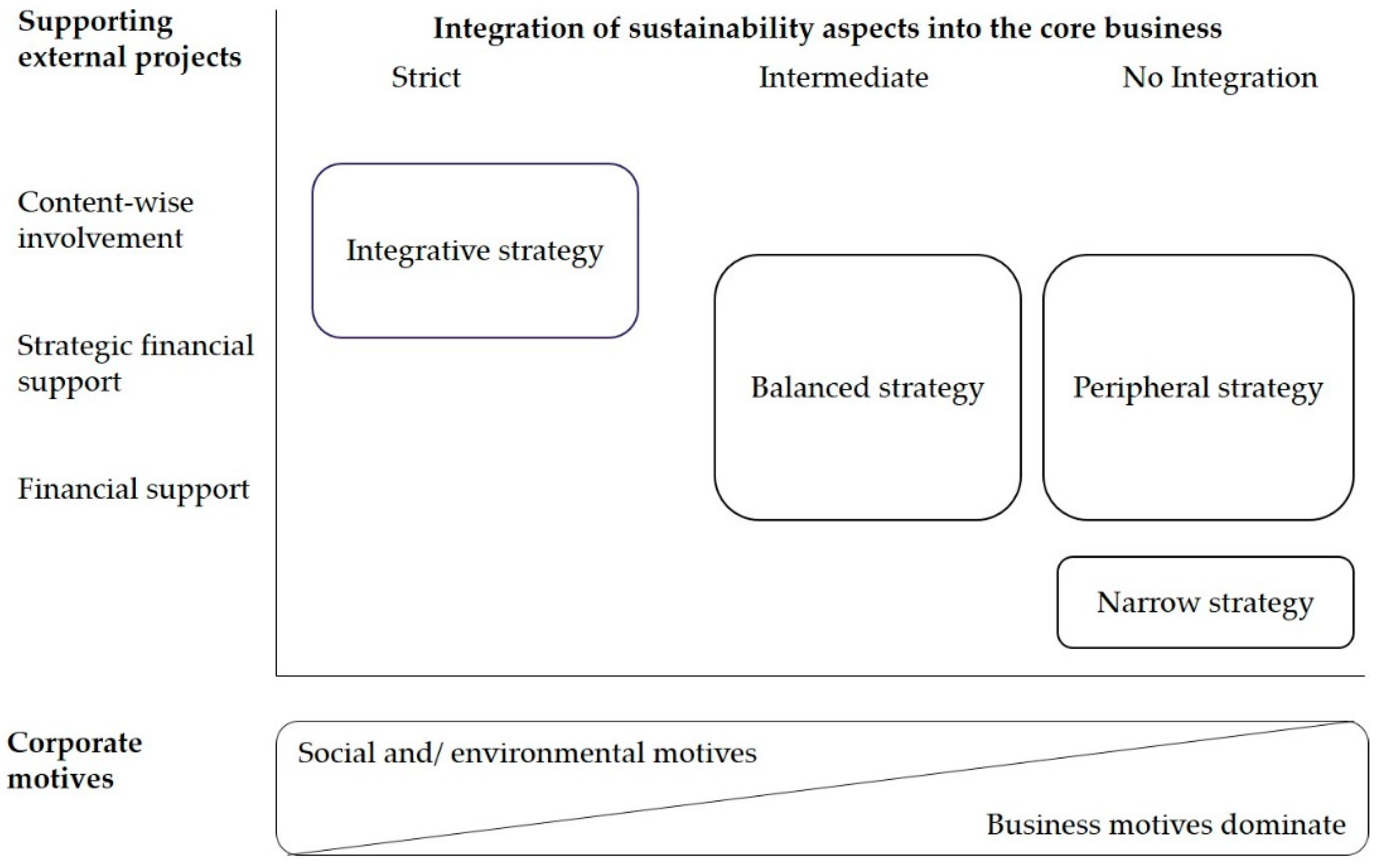

4. Results

4.1. Type 1: Narrow Strategy Content

4.2. Type 2: Peripheral Strategy Content

4.3. Type 3: Balanced Strategy Content

4.4. Type 4: Integrated Strategy Content with a Social Focus

4.5. Type 5: Integrated Strategy Content with an Environmental Focus

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Please first describe the position you hold within the company: What are your tasks? Which department are you assigned to?

- 2.

- Is your company committed to social/environmental issues? How did it come about? When did it happen? Why (not)? What’s the main motive?

- 3.

- What do you do when it comes to sustainability? How and when did this come about? Why (not)? Why (not)? What’s the main motive?

- 4.

- Are there any internal measures in the area of environmental protection? How did this happen? When? Why (not)? Why (not)? What’s the main motive?

- 5.

- Are there any internal social measures, e.g., any employee-related practices? How did this happen? When? Why (not)? Why (not)? What’s the main motive?

- 6.

- Are there any external social projects that support you? How did this happen? When? Why (not)? Why (not)? What’s the main motive?

- 7.

- Are there any external environmental projects that support you? How did this happen? When? Why (not)? What’s the main motive? Why (not)? What’s the main motive?

- 8.

- What role do environmental aspects play in your core business, e.g., in lending and investment decisions? How did this happen? When? Why (not)? Why (not)? What’s the main motive?

- 9.

- What role do social aspects play in your core business, e.g., in lending and investment decisions? How did this happen? When? Why (not)? Why (not)? What’s the main motive?

- 10.

- Are you planning to expand or limit your sustainable practices in the future? In what way? Why?

- 11.

- Do you pursue a certain strategy with your sustainable practice? What’s the overall aim?

- 12.

- To what extent does your sustainability strategy differ from the strategy of other banks? What do you do differently from other banks? Do you do more or less?

Appendix B

| First-Order Concepts | Second-Order Concepts | Aggregate Motive Categories |

| Stand up for the community Give back something to the community Promote the region | Contribution to public welfare | Social motives |

| Enable social participation Promote human rights Create equal opportunities | Contribution to social justice | |

| Enable voluntary work Support social commitment Promote social organizations | Contribution to social cohesion | |

| Do something for the environment Preserving resources Reduce emissions | Contribution to the climate footprint | Environmental motives |

| Make the green thought mainstream Function as a role mode | Contribution to environmental consciousness | |

| Reduce costs Stimulate additional business Reach the return on investment Reduce financial risks | Contribution to the financial performance | Business motives |

| Bind customers Meet customer expectations Attract new customers Exploit publicity purposes Differentiate against customers Improve image Become more known | Contribution to marketing-related motives | |

| Employee satisfaction Bind employees Motivate employees Finding adequate staff Reducing employees absence | Contribution to the employee-related motives |

References

- Louche, C.; Busch, T.; Crifo, P.; Marcus, A. Financial Markets and the Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy: Challenging the Dominant Logics. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Zsolnai, L.; Wasieleski, D.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Walker, T.; Weber, O.; Krosinsky, C.; Oram, D. Finance and Management for the Anthropocene. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, T.; Bauer, R.; Orlitzky, M. Sustainable Development and Financial Markets: Old Paths and New Avenues. Bus. Soc. 2016, 55, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O. Sustainability benchmarking of European banks and financial service organizations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2005, 12, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Atti, S.; Trotta, A.; Iannuzzi, A.P.; Demaria, F. Corporate Social Responsibility Engagement as a Determinant of Bank Reputation: An Empirical Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-W.; Shen, C.-H. Corporate social responsibility in the banking industry: Motives and financial performance. J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 3529–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangi, F.; Meles, A.; D’Angelo, E.; Daniele, L.M. Sustainable development and corporate governance in the financial system: Are environmentally friendly banks less risky? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 27, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Sanchez, P.; de la Cuesta-Gonzalez, M.; Paredes-Gazquez, J.D. Corporate social performance and its relation with corporate financial performance: International evidence in the banking industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Rahman, Z. The CSR’s influence on customer responses in Indian banking sector. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. The Formation of Customer CSR Perceptions in the Banking Sector: The Role of Coherence, Altruism, Expertise and Trustworthiness. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2015, 16, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O.; Feltmate, B. Sustainable Banking. Managing the Social and Environmental Impact of Financial Institutions; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ramiah, V.; Gregoriou, G.N. (Eds.) Handbook of Environmental and Sustainable Finance; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jeucken, M. Sustainable Finance and Banking: The Financial Sector and the Future of the Planet; Earthscan Publicatoin: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Thien, G.T.K. CSR for Clients’ Social/Environmental Impacts? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O.; Diaz, M.; Schwegler, R. Corporate Social Responsibility of the Financial Sector—Strengths, Weaknesses and the Impact on Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannsdottir, L. The Geneva Association framework for climate change actions of insurers: A case study of Nordic insurers. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 75, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O. Environmental Credit Risk Management in Banks and Financial Service Institutions. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2012, 21, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O.; Scholz, R.W.; Michalik, G. Incorporating sustainability criteria into credit risk management. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2010, 19, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbach, S.; Schiereck, D.; Trillig, J.; von Flotow, P. Sustainable Project Finance, the Adoption of the Equator Principles and Shareholder Value Effects. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2014, 23, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolakis, W.; Nelson, H.W.; Cohen, D.H. Who Pays Attention to Indigenous Peoples in Sustainable Development and Why?: Evidence From Socially Responsible Investment Mutual Funds in North America. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risi, D. Time and Business Sustainability: Socially Responsible Investing in Swiss Banks and Insurance Companies. Bus. Soc. 2018, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, A. Disentangling the Knot: Variable Mixing of Four Motivations for Firms’ Use of Social Practices. Bus. Soc. 2015, 54, 763–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Rahman, Z.; Kazmi, A.A. Corporate sustainability performance and firm performance research. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, S.; Fließ, S. Nachhaltigkeit als Gegenstand der Dienstleistungsforschung—Ergebnisse einer Zitationsanalyse. In Beiträge zur Dienstleistungsforschung 2016; Büttgen, M., Ed.; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 139–163. [Google Scholar]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Leonidou, L.C. Research into environmental marketing/management: A bibliographic analysis. Eur. J. Mark. 2011, 45, 68–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engert, S.; Baumgartner, R.J. Corporate sustainability strategy-bridging the gap between formulation and implementation. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, R. Strategic Leadership of Corporate Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Rauter, R. Strategic perspectives of corporate sustainability management to develop a sustainable organization. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warriner, C.K. The Problem of Organizational Purpose. Sociol. Q. 1965, 6, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almandoz, J. Arriving at the Starting Line: The Impact of Community and Financial Logics on New Banking Ventures. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1381–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almandoz, J. Founding Teams as Carriers of Competing Logics. Adm. Sci. Q. 2014, 59, 442–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, K. A Cognitive Perspective on the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015, 24, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, A.M.; de Bakker, F.G.A.; Groenewegen, P. Sustainability Struggles: Conflicting Cultures and Incompatible Logics. Bus. Soc. 2017, 21, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, J.; Webster, J.; Jenkin, T.A. Unmasking Corporate Sustainability at the Project Level: Exploring the Influence of Institutional Logics and Individual Agency. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Muff, K. Clarifying the Meaning of Sustainable Business: Introducing a Typology from Business-as-Usual to True Business Sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Korhonen, J. Strategic thinking for sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, F.; Figge, F.; Hahn, T. Planned or Emergent Strategy Making?: Exploring the Formation of Corporate Sustainability Strategies. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015, 25, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensen, E.F. Five types of organizational strategy. Scand. J. Manag. 2014, 30, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistoni, A.; Songini, L.; Perrone, O. The how and why of a firm’s approach to CSR and sustainability: A case study of a large European company. J. Manag. Gov. 2016, 20, 655–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, B.; Meyer, R. Strategy. Process, Content, Context: An International Perspective, 5th ed.; Cengage Learning: Singapore, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, R.J. Managing Corporate Sustainability and CSR: A Conceptual Framework Combining Values, Strategies and Instruments Contributing to Sustainable Development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Roth, K. Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Ebner, D. Corporate sustainability strategies: Sustainability profiles and maturity levels. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhaus, S.; Fawcett, S.E.; Knemeyer, M.A.; Fawcett, A.M. Motivations for environmental and social consciousness—Reevaluating the sustainability-based view. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 933–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brønn, P.S.; Vidaver-Cohen, D. Corporate Motives for Social Initiative: Legitimacy, Sustainability, or the Bottom Line? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Garay, L.; Jones, S. Sustainability motivations and practices in small tourism enterprises in European protected areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulraj, A. Environmental motivations: A classification scheme and its impact on environmental strategies and practices. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2009, 18, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shnayder, L.; van Rijnsoever, F.J.; Hekkert, M. Motivations for Corporate Social Responsibility in the packaged food industry: An institutional and stakeholder management perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 122, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Nyberg, D. An Inconvenient Truth: How Organizations Translate Climate Change into Business as Usual. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 1633–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hond, F.; de Bakker, F.G.A.; Doh, J. What Prompts Companies to Collaboration With NGOs?: Recent Evidence From the Netherlands. Bus. Soc. 2012, 54, 187–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Marrewijk, M.; Werre, M. Multiple levels of sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangle, S. Empirical analysis of determinants of adoption of proactive environmental strategies in India. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2009, 15, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaldon, P.; Gröschl, S. A Few Good Companies: Rethinking Firms’ Responsibilities Toward Common Pool Resources. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Scheermesser, M. Approaches to corporate sustainability among German companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauser, W.I. Ethics in Business: Answering the Call. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 58, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Burritt, R. Business Cases and Corporate Engagement with Sustainability: Differentiating Ethical Motivations. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, R.; Corsaro, D.; Montagnini, F.; Caruana, A. Corporate sustainability in action. Serv. Ind. J. 2014, 34, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S Back in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Multilevel Theory of Social Change in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J.; Mazereeuw-Van der Duijn Schouten, C. Motives for Corporate Social Responsibility. Economist 2012, 160, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, K.; Trendafilova, S. CSR and environmental responsibility: Motives and pressures to adopt green management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Ostrom, A.L.; Corus, C.; Fisk, R.P.; Gallan, A.S.; Giraldo, M.; Mende, M.; Mulder, M.; Rayburn, S.W.; Rosenbaum, M.S.; et al. Transformative service research: An agenda for the future. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Wallis, M.; Klein, C. Ethical requirement and financial interest: A literature review on socially responsible investing. Bus. Res. 2015, 8, 61–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, J.E.; Warren, G.J.; Boon, J. What is Different about Socially Responsible Funds? A Holdings-Based Analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjaliès, D.-L. A Social Movement Perspective on Finance: How Socially Responsible Investment Mattered. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crifo, P.; Mottis, N. Socially Responsible Investment in France. Bus. Soc. 2016, 55, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haack, P.; Schoeneborn, D.; Wickert, C. Talking the Talk, Moral Entrapment, Creeping Commitment? Exploring Narrative Dynamics in Corporate Responsibility Standardization. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 815–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wörsdorfer, M. Equator Principles: Bridging the Gap between Economics and Ethics? Bus. Soc. Rev. 2015, 120, 205–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, E.J.M. Effective Shareholder Engagement: The Factors that Contribute to Shareholder Salience. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.; Arenas, D. Engaging Ethically: A Discourse Ethics Perspective on Social Shareholder Engagement. Bus. Ethics Q. 2015, 25, 163–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.; Louche, C.; van Cranenburgh, K.C.; Arenas, D. Social Shareholder Engagement: The Dynamics of Voice and Exit. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soana, M.-G. The Relationship Between Corporate Social Performance and Corporate Financial Performance in the Banking Sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Kim, H.; Park, K. Corporate Environmental Responsibility and Firm Performance in the Financial Services Sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. Corporate social responsibility and customer loyalty: Exploring the role of identification, satisfaction and type of company. J. Serv. Mark. 2015, 29, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals; 2015; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2012, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golafshani, N. Understanding Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Spiggle, S. Analysis and Interpretation of Qualitative Data in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Mental Health 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kluge, S. Empirically Grounded Construction of Types and Typologies in Qualitative Social Research. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung 2000, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Bao, Y.; Verbeke, A. Integrating CSR Initiatives in Business: An Organizing Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarsfeld, P. Some remarks on typological procedures in social research. Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung 1939, 6, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.L.; Bennett, A. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, K.H. Typologies and Taxonomies: An Introduction to Classification Techniques; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Li, Z.; Yang, C. Measuring firm size in empirical corporate finance. J. Bank. Financ. 2018, 86, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lo, C.W.-H.; Li, P.H.Y. Organizational Visibility, Stakeholder Environmental Pressure and Corporate Environmental Responsiveness in China. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreck, P.; Raithel, S. Corporate Social Performance, Firm Size, and Organizational Visibility: Distinct and Joint Effects on Voluntary Sustainability Reporting. Bus. Soc. 2018, 57, 742–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilert, M.; Walker, K.; Dogan, J. Can Ivory Towers be Green? The Impact of Organization Size on Organizational Social Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantouvakis, A.; Vlachos, I.; Zervopoulos, P.D. Market orientation for sustainable performance and the inverted-U moderation of firm size: Evidence from the Greek shipping industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Y.; Liu, M. Organizational structure, slack resources and sustainable corporate socially responsible performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, K. Reexamining the Expected Effect of Available Resources and Firm Size on Firm Environmental Orientation: An Empirical Study of UK Firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 65, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, F.E. Does Size Matter?: Organizational Slack and Visibility as Alternative Explanations for Environmental Responsiveness. Bus. Soc. 2002, 41, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Framework of Corporate Water Responsibility. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, R.; Alford, R. Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices and institutional contradictions. In The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis; Powell, W.W., DiMaggio, P.J., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991; pp. 232–263. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, P.H.; Ocasio, W.; Lounsbury, M. The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure, and Process; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ocasio, W.; Loewenstein, J.; Nigam, A. How Streams of Communication Reproduce and Change Institutional Logics: The Role of Categories. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, J.L.; Berrone, P.; Phan, P.H. Corporate governance and environmental performance: Is there really a link? Strat. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 885–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.; Li, Z.; Minor, D. Corporate Governance and Executive Compensation for Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Hussain, N.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. An empirical analysis of the complementarities and substitutions between effects of ceo ability and corporate governance on socially responsible performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Ni, N.; Dyck, B. Recipes for Successful Sustainability: Empirical Organizational Configurations for Strong Corporate Environmental Performance. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015, 24, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, A.; Qiu, Y.; Trojanowski, G. Board Attributes, Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy, and Corporate Environmental and Social Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachiller, P.; Garcia-Lacalle, J. Corporate governance in Spanish savings banks and its relationship with financial and social performance. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 828–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.J.; Hoitash, R.; Hoitash, U. The Heterogeneity of Board-Level Sustainability Committees and Corporate Social Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 1161–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmagrhi, M.H.; Ntim, C.G.; Elamer, A.A.; Zhang, Q. A study of environmental policies and regulations, governance structures, and environmental performance: The role of female directors. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasser, Q.R.; Al Mamun, A.; Ahmed, I. Corporate Social Responsibility and Gender Diversity: Insights from Asia Pacific. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, C.; Cook, A.; Ingersoll, A.R. Do Women Leaders Promote Sustainability? Analyzing the Effect of Corporate Governance Composition on Environmental Performance. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2016, 25, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Y.; Ntim, C.G.; Chengang, Y.; Ullah, F.; Fosu, S. Environmental policy, environmental performance, and financial distress in China: Do top management team characteristics matter? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 1635–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, M.A.; Raffaelli, R. Logic pluralism, organizational design, and practice adoption the structural embeddedness of CSR programs. In Institutional Logics in Action, Part B, 2013; Lounsbury, M., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; Volume 39, Pt B, pp. 175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann, K.; Zwergel, B.; Gold, S.; Seuring, S.; Klein, C. Exploring the Supply-Demand-Discrepancy of Sustainable Financial Products in Germany from a Financial Advisor’s Point of View. Sustainability 2018, 10, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, N. Impacts of the Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement: Effects on Finance, Policy and Public Discourse. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.-L.; Pfleger, R. Business transformation towards sustainability. Bus. Res. 2014, 7, 313–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and Society: The Link Between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, L.; Cuestas, P.J.; Román, S. Determinants of Consumer Attributions of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.D.T.; van der Meer, M. Exploring the Congruence Between Organizations and Their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Activities. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zimmermann, S. Same Same but Different: How and Why Banks Approach Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082267

Zimmermann S. Same Same but Different: How and Why Banks Approach Sustainability. Sustainability. 2019; 11(8):2267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082267

Chicago/Turabian StyleZimmermann, Salome. 2019. "Same Same but Different: How and Why Banks Approach Sustainability" Sustainability 11, no. 8: 2267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082267

APA StyleZimmermann, S. (2019). Same Same but Different: How and Why Banks Approach Sustainability. Sustainability, 11(8), 2267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082267