Mediating Bullying and Strain in Higher Education Institutions: The Case of Pakistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Understanding the Specificity of Bullying in HEI

2. Literature Review

3. Methodological Framework

3.1. The Sample

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Workplace Bullying Scale (WBS)

3.2.2. COPE Inventory

3.2.3. Workplace Bullying Strain Scale (WBSS)

3.2.4. Procedure

4. Key Findings

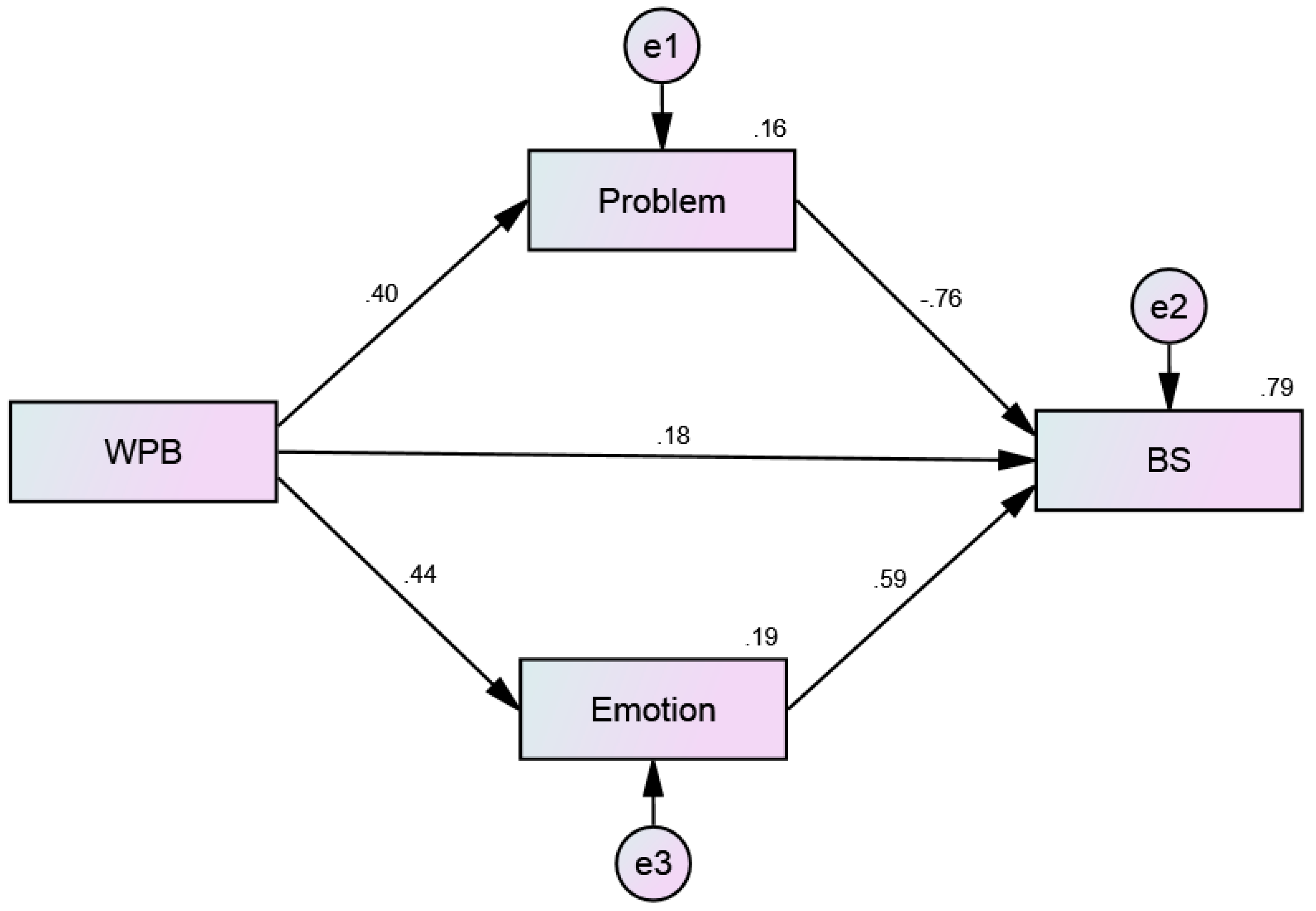

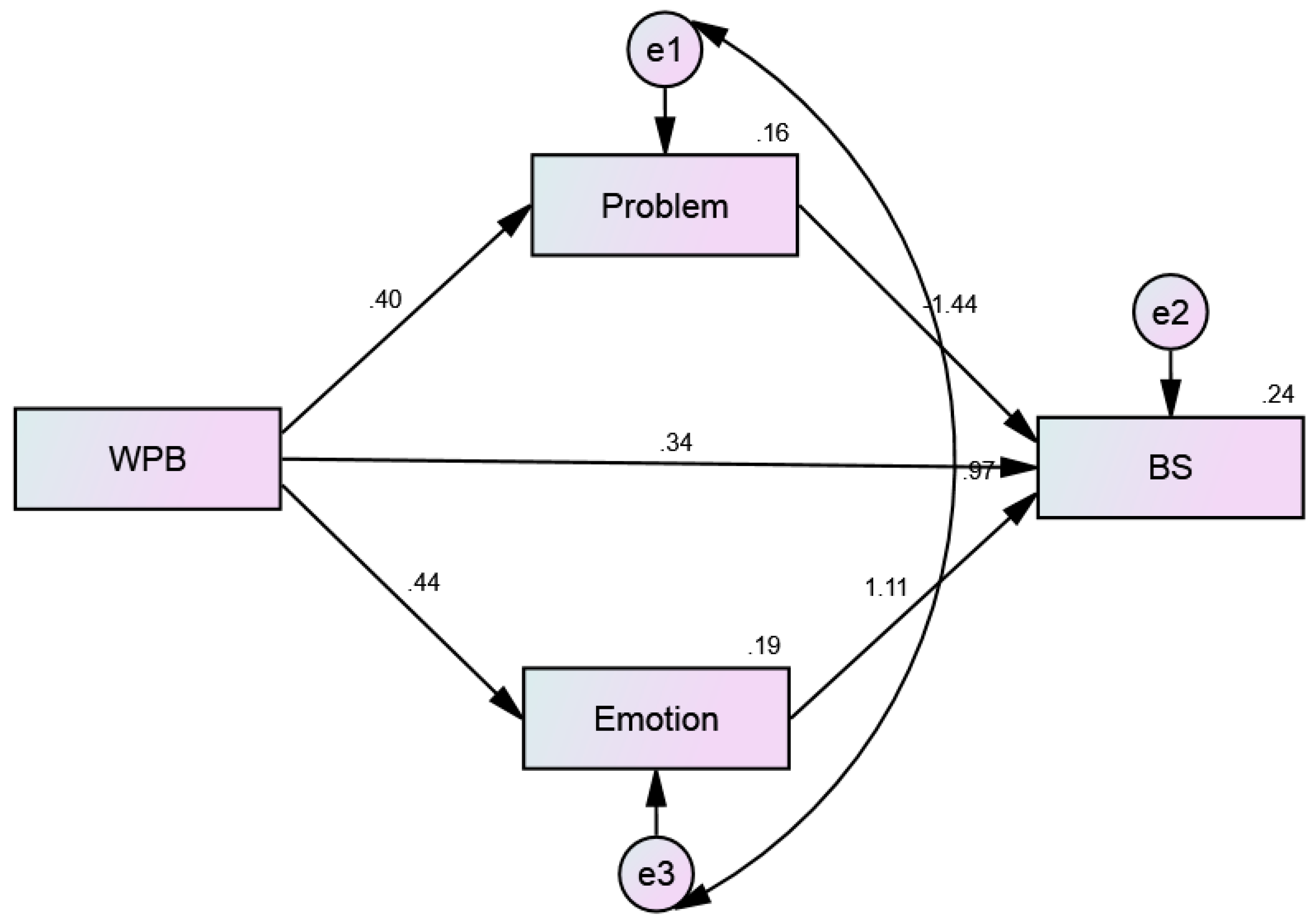

Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Statement

References

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Notelaers, G. Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the negative acts questionnaire—Revised. Work Stress 2009, 23, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meares, M.; Oetzel, J.G.; Derkacs, D.; Ginossar, T. Employee mistreatment and muted voices in the culturally diverse workforce. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2004, 32, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, M.; Barker, M.; Rayner, C. Applying strategies for dealing with workplace bullying. Int. J. Manpow. 1999, 20, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutgen-Sandvik, P. Take This Job and …: Quitting and Other Forms of Resistance to Workplace Bullying. Commun. Monogr. 2006, 73, 406–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, P.; Huynh, A.; Goodman-Delahunty, J. Defining workplace bullying behaviour professional lay definitions of workplace bullying. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2007, 30, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Karim, S.; Parbudyal, S. 20 Years of workplace bullying research: A review of the antecedents and consequences of bullying in the workplace. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2012, 17, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, S.; Murray, J. Workplace bullying: Is lack of understanding the reason for inaction? Organ. Dyn. 2015, 44, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvizi, A.; Lytras, M.D.; Daniela, L. The Future of Innovation and Technology in Education: A Case for Restoring the Role of the Teacher as a Mentor. In The Future of Innovation and Technology in Education: Policies and Practices for Teaching and Learning Excellence; Visvizi, A., Lytras, M.D., Daniela, L., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 1–10. ISBN 9781787565562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniela, L.; Visvizi, A.; Gutiérrez-Braojos, C.; Lytras, M.D. Sustainable Higher Education and Technology-Enhanced Learning (TEL). Sustainability 2018, 10, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.; Stallworth, L.E. The battered apple: An application of stressor-emotion control/support theory to teachers’ experience of violence and bullying. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 927–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S. The nature and causes of bullying at work. Int. J. Manpow. 1999, 20, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. From Brain Drain to Brain Gain. 6 May 2018. Available online: https://dailytimes.com.pk/236471/from-brain-drain-to-brain-gain/ (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Shadman, A. Pakistan’s Higher Education in Crisis. 1 August 2017. Available online: https://propakistani.pk/2017/08/01/pakistans-higher-education-crisis-govt-shifts-funds-transport-schemes/ (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Keelan, E. Bully for you. Accountancy 2000, 125, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Namie, G.; Namie, R. The Bully at Work: What You Can Do to Stop the Hurt and Reclaim Your Dignity on the Job; Sourcebooks: Naperville, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Keashly, L.; Neuman, J.H. Faculty Experiences with Bullying in Higher Education. Adm. Theory Prax. 2010, 32, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misawa, M.; Rowland, M.L. Academic Bullying and Incivility in Adult, Higher, Continuing, and Professional Education. Adult Learn. 2015, 26, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabrodska, K.; Kveton, P. Prevalence and Forms of Workplace Bullying Among University Employees. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2013, 25, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Connor-Smith, J. Personality and coping. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief cope. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, N.; Jawaid, M.; Haider, I.I.; Masood, Z. Bullying of junior doctors in Pakistan: A cross-sectional survey. Singap. Med. J. 2010, 51, 592–595. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, D.; Gross, C. Conflict escalation and coping with workplace bullying: A replication and extension. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2001, 10, 497–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, A.; Shoukat, A. Workplace bullying: Prevalence and risk groups in a Pakistani sample. J. Public Adm. Gov. 2013, 3, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, A.; Muazzam, A. An Assessment of Workplace Bullying in Educational Institutes of Lahore, Pakistan. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Lahore College for Women University, Punjab, Pakistan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J.L. IBM® SPSS® Amos™ 21 User’s Guide; Amos Development Corporation, IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen, E.G.; Einarsen, S. Basic assumptions and post-traumatic stress among victims of workplace bullying. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2002, 11, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. Workplace bullying—Interim findings of a study in further and higher education in wales. Int. J. Manpow. 1999, 20, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckay, R.; Arnold, D.; Fratzl, J.; Thomas, R. Workplace bullying in academia: A Canadian study. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2008, 20, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.; Cohen, C. Dangerous work: The gendered nature of bullying in the context of higher education. Gend. Work Organ. 2004, 11, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, A.B.; Veldhoven, M.V. Risk sectors for undesirable behavior and mobbing. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2001, 10, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, C. From research to implementation: Finding leverage for prevention. Int. J. Manpow. 1999, 20, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keashly, L. Emotional abuse in the workplace: Conceptual and empirical issues. J. Emot. Abus. 1998, 1, 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafsson, R.F.; Johannsdottir, H.L. Coping with bullying in the workplace: The effect of gender, age and type of bullying. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2004, 32, 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Jimenez, B.; Rodriguez-Munoz, A.; Salin, D.; Benadero, M. Workplace bullying in southern Europe: Prevalence, forms and risk groups in a Spanish sample. Int. J. Organ. Behav. 2008, 13, 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Deniz, N.; Ertosun, N.D. The relationship between personality and being exposed to workplace bullying or mobbing. J. Glob. Strateg. Manag. 2010, 7, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz, P.; Noronha, E. Protecting my interests: HRM and targets’ coping with workplace bullying. Qual. Rep. 2010, 15, 507–534. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bullying | - | - | - | - |

| 2. Problem-focused coping | 0.40 ** | - | - | - |

| 3. Emotion-focused coping | 0.44 ** | 0.88 ** | - | - |

| 4. Strain | 0.25 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.21 ** | - |

| Mean and SD | 53.84 ± 10.63 | 23.72 ± 10.26 | 22.60 ± 10.11 | 92.14 ± 25.75 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.84 |

| Variables | M (SD) | t (398) | P | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 48.90 (7.67) | −10.50 | 0.001 | 1.05 |

| Female | 58.79 (10.88) | |||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 50.1 (8.74) | −14.53 | 0.001 | 1.70 |

| Unmarried | 64.60 (8.17) | |||

| Nature of job | ||||

| Permanent | 50.30 (8.63) | −15.93 | 0.001 | 2.12 |

| Contract | 67.10 (6.86) | |||

| Work experience | ||||

| >5 years | 50.30 (12.48) | −8.72 | 0.001 | 0.83 |

| <5 years | 59.02 (8.02) |

| Variable | Source of Variance | Df | SS | MS | F | P | η² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Between-group | 3 | 9627.57 | 5379.99 | |||

| Within-group | 396 | 35,460.12 | 73.10 | 73.59 | 0.000 | 0.21 | |

| Total | 399 | 45,087.69 | |||||

| Rank | Between-group | 3 | 16,139.98 | 5379.99 | |||

| Within-group | 396 | 28,947.71 | 72.09 | 73.59 | 0.000 | 0.35 | |

| Total | 399 | 45,087.69 |

| Model | Χ2 | Df | χ²/df | CFI | GFI | NNFI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial M | 108.00 | 1 | 108.100 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Final M | 0.07 | 1 | 0.07 | 99 | 1 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Predictor | Outcome | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bullying | Strain | 0.34 | −0.09 | 0.25 | 0.211 |

| Bullying | Problem-focused coping | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.001 |

| Bullying | Emotion-focused coping | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.001 |

| Problem-focused coping | Strain | 1.44 | 0.00 | 1.43 | 0.001 |

| Emotion-focused coping | Strain | 1.11 | 0.00 | 1.11 | 0.001 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anjum, A.; Muazzam, A.; Manzoor, F.; Visvizi, A.; Nawaz, R. Mediating Bullying and Strain in Higher Education Institutions: The Case of Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082244

Anjum A, Muazzam A, Manzoor F, Visvizi A, Nawaz R. Mediating Bullying and Strain in Higher Education Institutions: The Case of Pakistan. Sustainability. 2019; 11(8):2244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082244

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnjum, Ambreen, Amina Muazzam, Farkhanda Manzoor, Anna Visvizi, and Raheel Nawaz. 2019. "Mediating Bullying and Strain in Higher Education Institutions: The Case of Pakistan" Sustainability 11, no. 8: 2244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082244

APA StyleAnjum, A., Muazzam, A., Manzoor, F., Visvizi, A., & Nawaz, R. (2019). Mediating Bullying and Strain in Higher Education Institutions: The Case of Pakistan. Sustainability, 11(8), 2244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082244