Visitor Perceptions and Effectiveness of Place Branding Strategies in Thematic Parks in Bandung City Using Text Mining Based on Google Maps User Reviews

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Thematic Parks

2.2. The Place Branding of Public Parks

2.3. Visitors’ Perceptions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Site

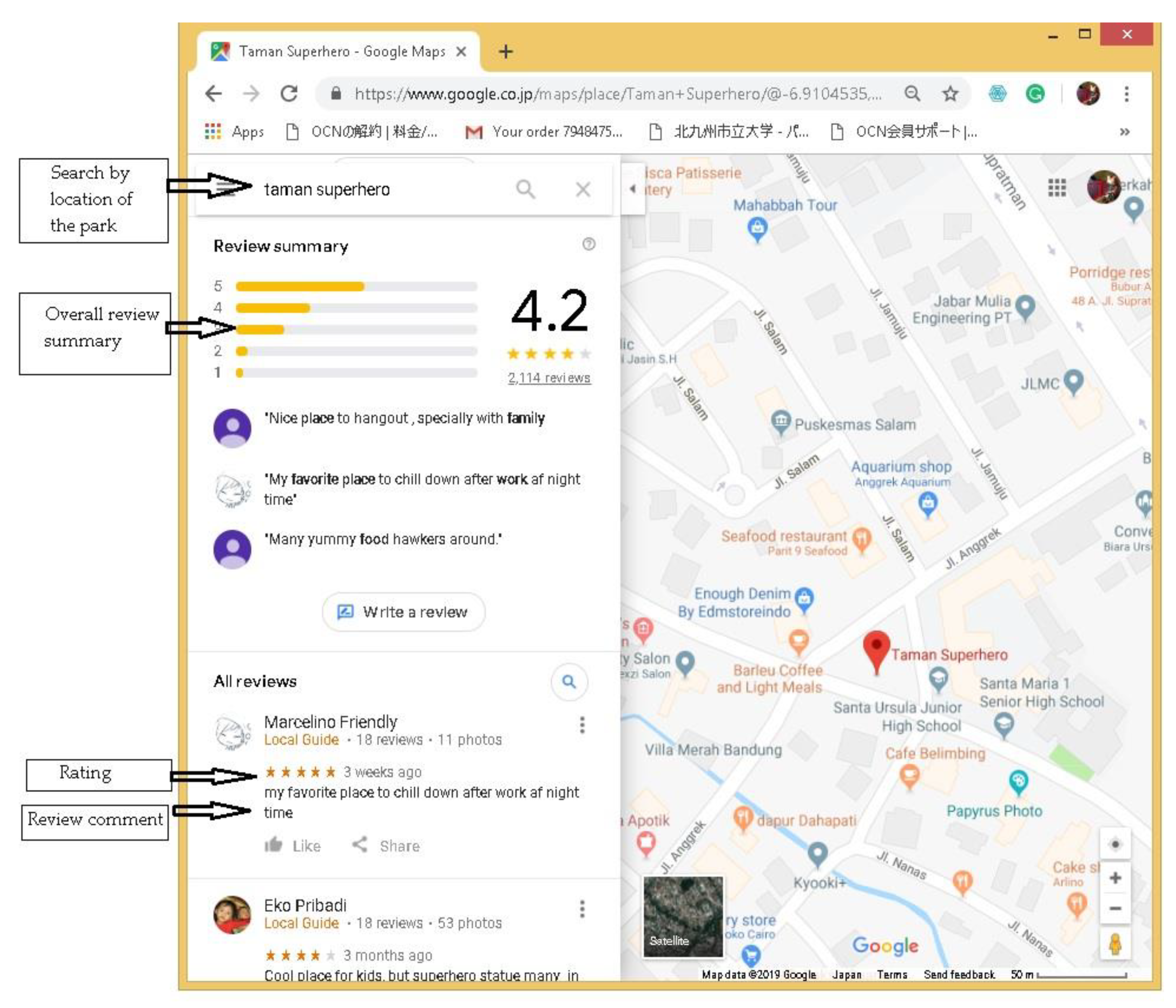

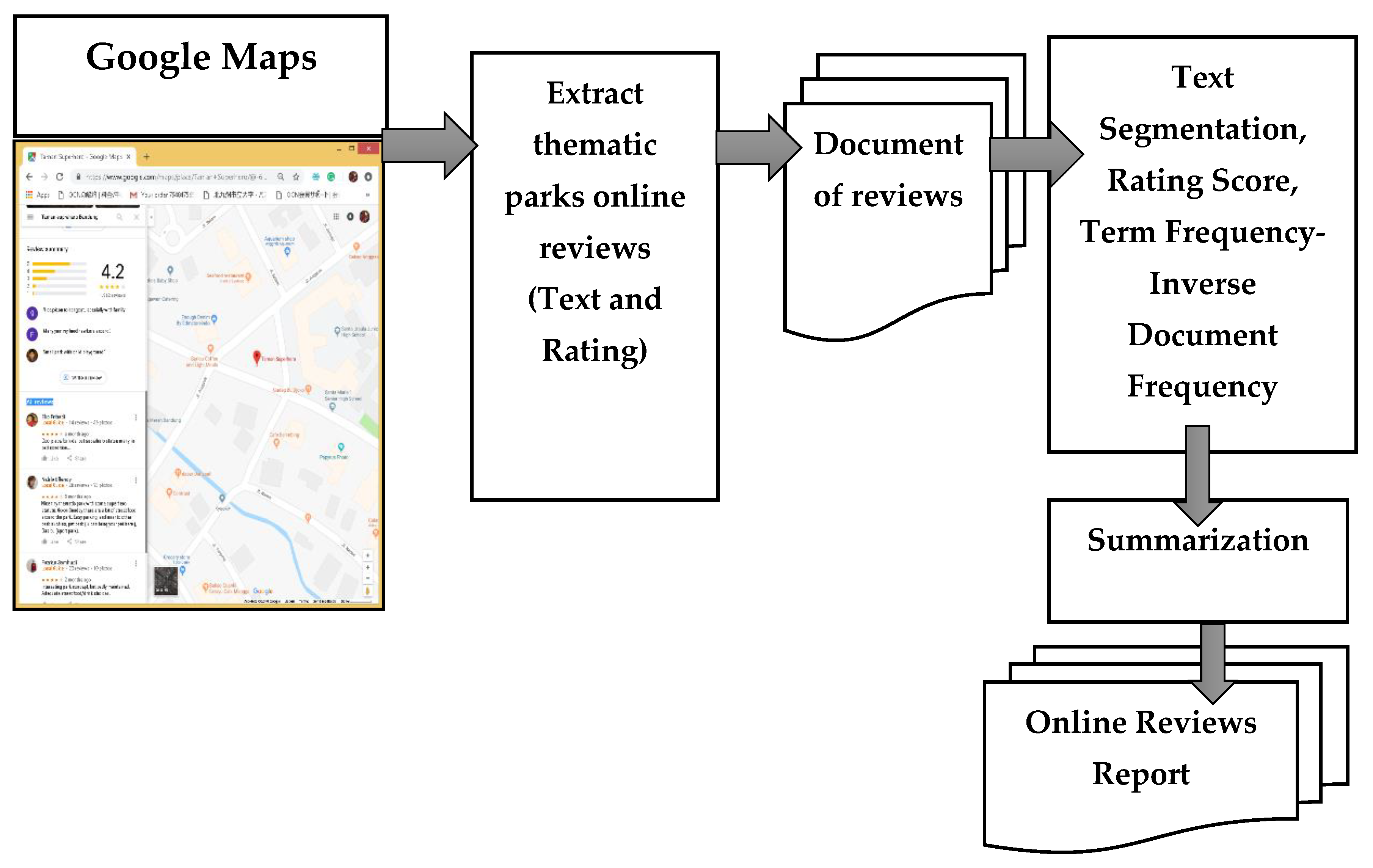

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Text Analysis

3.4. Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency

4. Results and Discussion

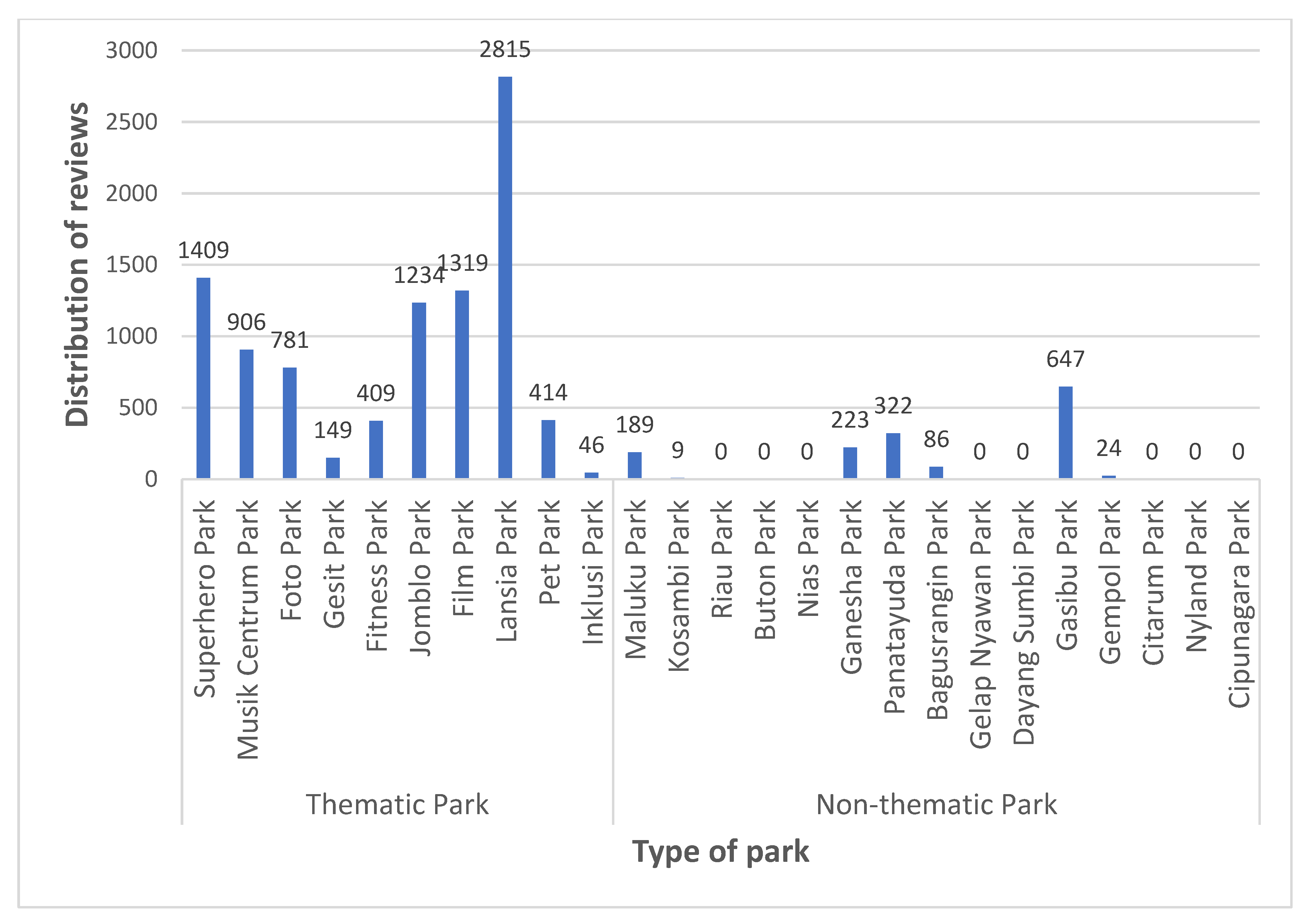

4.1. Comparison of Online Reviews of Thematic Parks and Non-Thematic Parks

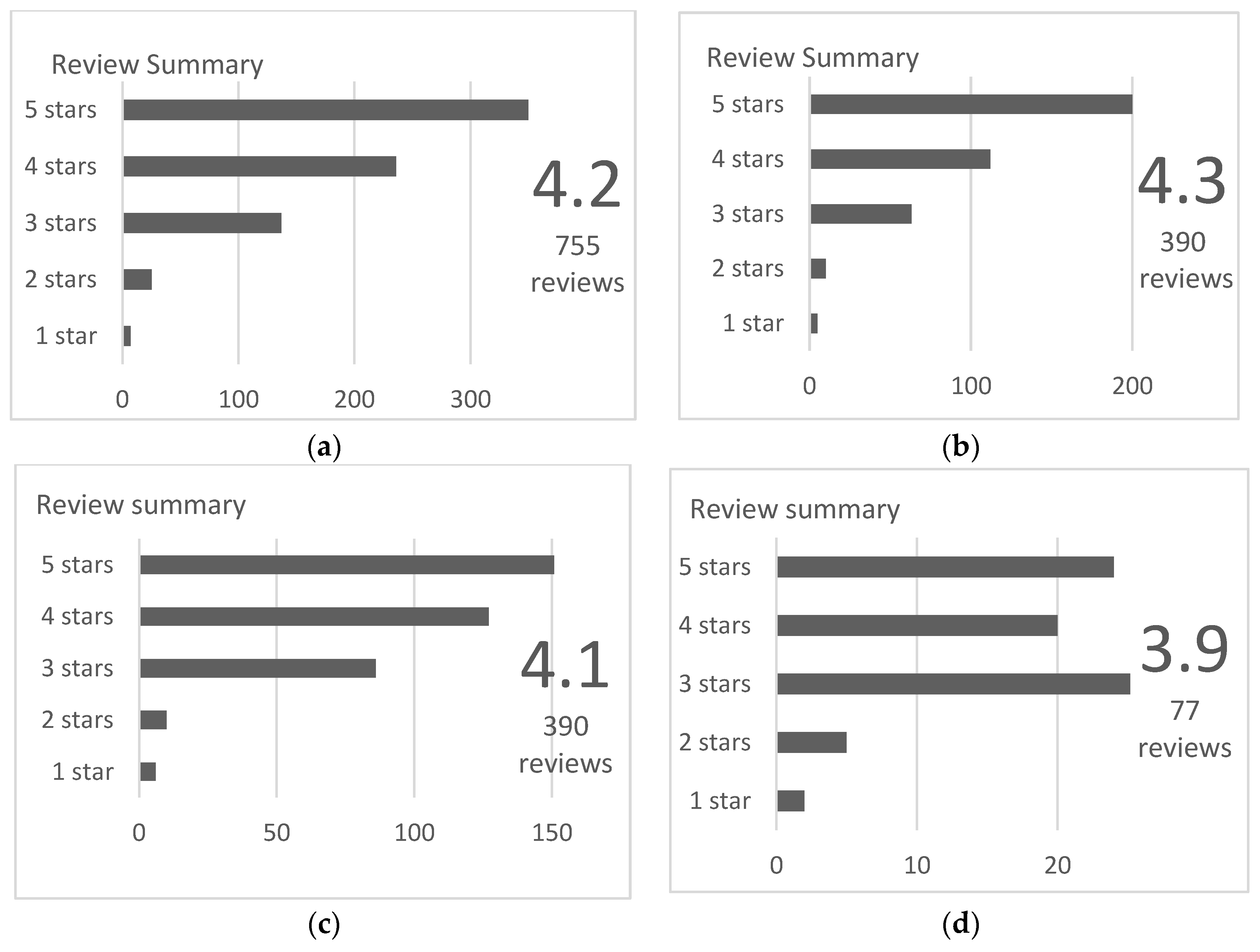

4.2. Review Summary of Thematic Park Rating Distribution

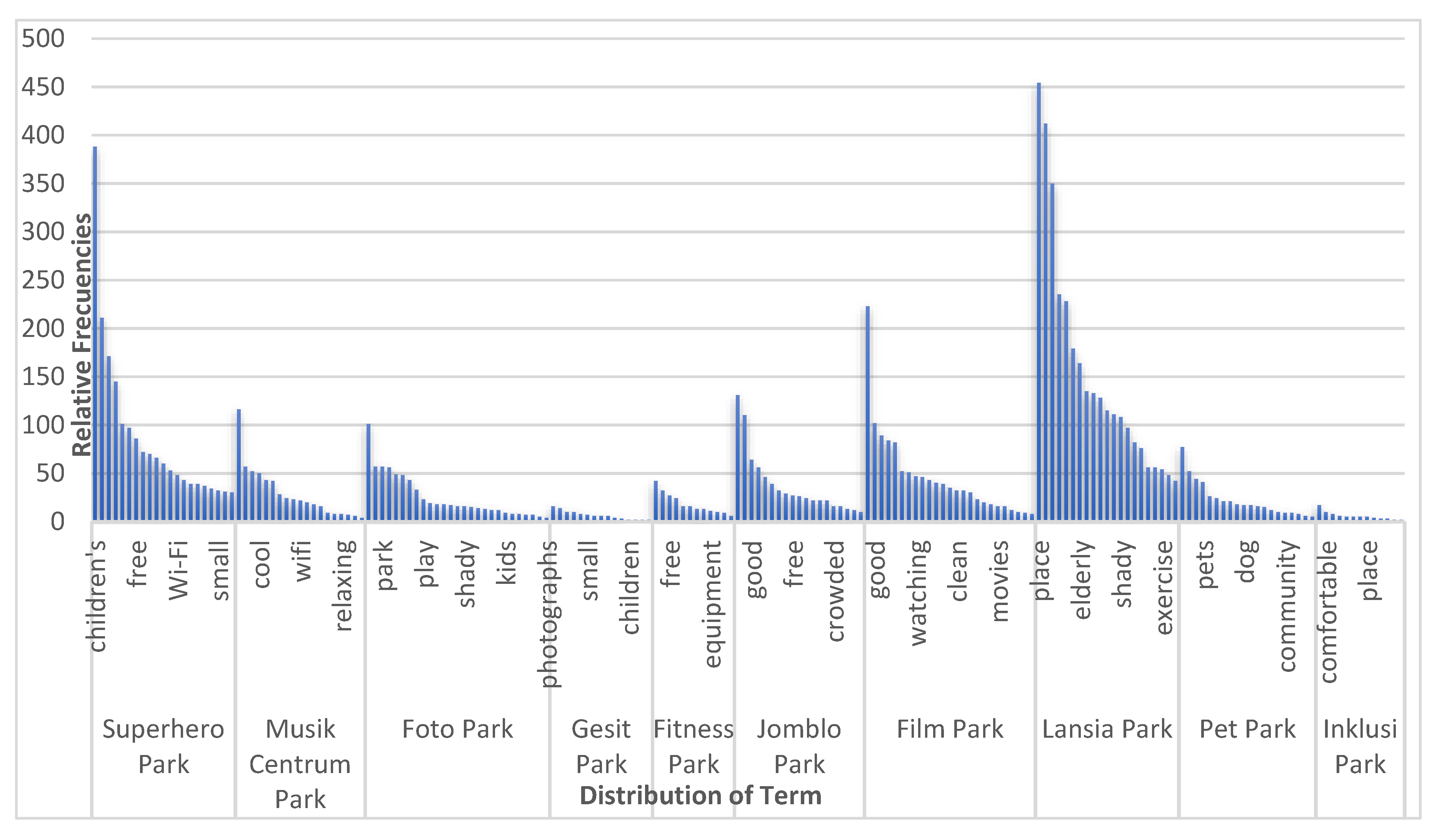

4.3. The Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Term | Count | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| children’s | 388 | 0.03773952 |

| park | 211 | 0.020523295 |

| place | 171 | 0.016632624 |

| play | 145 | 0.014103686 |

| good | 101 | 0.009823947 |

| suitable | 97 | 0.00943488 |

| free | 86 | 0.008364945 |

| superheroes | 72 | 0.00700321 |

| statues | 70 | 0.006808676 |

| comfortable | 66 | 0.006419609 |

| playground | 60 | 0.005836008 |

| nice | 53 | 0.005155141 |

| Wi-Fi | 48 | 0.004668807 |

| family | 43 | 0.004182472 |

| crowded | 39 | 0.003793405 |

| playing | 39 | 0.003793405 |

| like | 37 | 0.003598872 |

| fun | 34 | 0.003307071 |

| small | 32 | 0.003112538 |

| facilities | 31 | 0.003015271 |

| clean | 30 | 0.002918004 |

| Term | Count | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| place | 116 | 0.035452 |

| music | 57 | 0.017421 |

| good | 52 | 0.015892 |

| cool | 50 | 0.015281 |

| nice | 43 | 0.013142 |

| hangout | 28 | 0.008557 |

| comfortable | 24 | 0.007335 |

| free | 23 | 0.007029 |

| Wi-Fi | 22 | 0.006724 |

| suitable | 20 | 0.006112 |

| shady | 18 | 0.005501 |

| play | 16 | 0.00489 |

| crowded | 9 | 0.002751 |

| musical | 8 | 0.002445 |

| relaxing | 8 | 0.002445 |

| community | 7 | 0.002139 |

| practice | 6 | 0.001834 |

| musicians | 4 | 0.001222 |

| Term | Count | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| place | 101 | 0.029208 |

| nice | 57 | 0.016484 |

| park | 57 | 0.016484 |

| good | 56 | 0.016194 |

| cool | 49 | 0.01417 |

| Wi-Fi | 48 | 0.013881 |

| free | 43 | 0.012435 |

| comfortable | 33 | 0.009543 |

| play | 23 | 0.006651 |

| bandung | 19 | 0.005495 |

| clean | 18 | 0.005205 |

| relax | 18 | 0.005205 |

| photo | 17 | 0.004916 |

| shady | 16 | 0.004627 |

| family | 15 | 0.004338 |

| suitable | 14 | 0.004049 |

| hangout | 13 | 0.003759 |

| facilities | 12 | 0.00347 |

| playground | 12 | 0.00347 |

| kids | 9 | 0.002603 |

| crowded | 8 | 0.002313 |

| relaxing | 8 | 0.002313 |

| photos | 7 | 0.002024 |

| photography | 5 | 0.001446 |

| Term | Count | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| park | 16 | 0.023155 |

| place | 14 | 0.02026 |

| maintained | 10 | 0.014472 |

| nice | 10 | 0.014472 |

| good | 8 | 0.011577 |

| small | 7 | 0.01013 |

| comfortable | 6 | 0.008683 |

| relaxing | 6 | 0.008683 |

| Wi-Fi | 6 | 0.008683 |

| suitable | 4 | 0.005789 |

| shady | 3 | 0.004342 |

| children | 2 | 0.002894 |

| playground | 2 | 0.002894 |

| facilities | 2 | 0.002894 |

| hangout | 2 | 0.002894 |

| Term | Count | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| place | 42 | 0.024207 |

| fitness | 32 | 0.018444 |

| free | 27 | 0.015562 |

| good | 24 | 0.013833 |

| nice | 16 | 0.009222 |

| sports | 16 | 0.009222 |

| jogging | 13 | 0.007493 |

| Wi-Fi | 13 | 0.007493 |

| equipment | 11 | 0.00634 |

| gym | 10 | 0.005764 |

| comfortable | 9 | 0.005187 |

| shady | 6 | 0.003458 |

| Term | Count | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| place | 131 | 0.023862 |

| park | 110 | 0.020036 |

| good | 64 | 0.011658 |

| singles | 56 | 0.0102 |

| nice | 46 | 0.008379 |

| cool | 39 | 0.007104 |

| comfortable | 32 | 0.005829 |

| Wi-Fi | 29 | 0.005282 |

| free | 27 | 0.004918 |

| hangout | 26 | 0.004736 |

| skate | 24 | 0.004372 |

| single | 22 | 0.004007 |

| suitable | 22 | 0.004007 |

| young | 22 | 0.004007 |

| crowded | 16 | 0.002914 |

| skateboarding | 16 | 0.002914 |

| unique | 13 | 0.002368 |

| flyover | 12 | 0.002186 |

| noisy | 10 | 0.001821 |

| Term | Count | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| place | 223 | 0.030286567 |

| good | 102 | 0.013853049 |

| park | 89 | 0.012087464 |

| nice | 84 | 0.011408393 |

| comfortable | 82 | 0.011136765 |

| suitable | 52 | 0.007062339 |

| cool | 51 | 0.006926525 |

| watching | 47 | 0.006383268 |

| family | 46 | 0.006247453 |

| children | 43 | 0.005840011 |

| play | 40 | 0.005432568 |

| film | 39 | 0.005296754 |

| free | 35 | 0.004753497 |

| clean | 32 | 0.004346055 |

| movie | 32 | 0.004346055 |

| screen | 30 | 0.004074426 |

| gathering | 23 | 0.003123727 |

| relaxing | 20 | 0.002716284 |

| kids | 18 | 0.002444656 |

| movies | 16 | 0.002173027 |

| Wi-Fi | 16 | 0.002173027 |

| unique | 12 | 0.001629771 |

| facilities | 10 | 0.001358142 |

| community | 9 | 0.001222328 |

| crowded | 8 | 0.001086514 |

| Term | Count | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| place | 454 | 0.019863 |

| cool | 412 | 0.018025 |

| park | 350 | 0.015313 |

| comfortable | 235 | 0.010281 |

| good | 228 | 0.009975 |

| nice | 179 | 0.007831 |

| elderly | 164 | 0.007175 |

| Bandung | 135 | 0.005906 |

| city | 133 | 0.005819 |

| suitable | 128 | 0.0056 |

| family | 115 | 0.005031 |

| clean | 111 | 0.004856 |

| shady | 108 | 0.004725 |

| jogging | 97 | 0.004244 |

| beautiful | 82 | 0.003588 |

| Wi-Fi | 76 | 0.003325 |

| relaxing | 56 | 0.00245 |

| sports | 56 | 0.00245 |

| exercise | 54 | 0.002363 |

| crowded | 48 | 0.0021 |

| children | 42 | 0.001838 |

| Term | Count | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| place | 77 | 0.033304498 |

| pet | 52 | 0.022491349 |

| park | 44 | 0.019031141 |

| pets | 41 | 0.017733565 |

| animal | 26 | 0.011245674 |

| bring | 24 | 0.010380623 |

| good | 21 | 0.009083045 |

| lovers | 21 | 0.009083045 |

| animals | 18 | 0.007785467 |

| dog | 17 | 0.007352941 |

| nice | 17 | 0.007352941 |

| dogs | 16 | 0.006920415 |

| cool | 15 | 0.006487889 |

| play | 12 | 0.005190312 |

| gathering | 10 | 0.00432526 |

| community | 9 | 0.003892734 |

| suitable | 9 | 0.003892734 |

| comfortable | 8 | 0.003460208 |

| facilities | 6 | 0.002595156 |

| Wi-Fi | 5 | 0.00216263 |

| Term | Count | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| park | 17 | 0.029462738 |

| comfortable | 10 | 0.017331023 |

| city | 8 | 0.013864818 |

| Bandung | 6 | 0.010398613 |

| cool | 5 | 0.008665511 |

| facilities | 5 | 0.008665511 |

| people | 5 | 0.008665511 |

| place | 5 | 0.008665511 |

| disabilities | 4 | 0.006932409 |

| clean | 3 | 0.005199307 |

| relaxing | 3 | 0.005199307 |

| children | 2 | 0.003466205 |

| family | 2 | 0.003466205 |

References

- Lyytimäki, J.; Sipilä, M. Hopping on one leg—The challenge of ecosystem disservices for urban green management. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, M.M.; Vardanyan, Z. The Benefits of Urban Parks, a Review of Urban Research. J. Novel Appl. Sci. 2013, 2, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Fauziah, A.; Santosa, I.; Wahjudi, D. Thematic Concept on The Physical Element of Open Space towards People’s Place Attachment in the City of Bandung. Glob. J. Art Hum. Soc. Sci. 2016, 4, 48–65. [Google Scholar]

- Andani, R.; Setiyorini, H. Comparative Study of Local People and Tourist Perception through Developing Thematic City Park in Bandung and Surabaya. In Proceedings of the 1st SOSEIC 2015, Social Science and Economics International Conference, Palembang, Indonesia, 20–21 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Loures, L.; Santos, R.; Panagopoulos, T. Urban Parks and Sustainable City—The Case of Portimao, Portugal. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2007, 3, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ruzinskaite, J. Place Branding: The Need for an Evaluative Framework. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H. Marketing and Cases of Choice Cases; Center for Academic Publishing Service: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Robby, Y.T.; Martheas, I.; Jian-Ping, S. The Effectiveness of Green Infrastructure Concept Design at City Parks, Bandung City, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Hydroscience & Engineering, Tainan, Taiwan, 6–10 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nururohmah, Z. Share-power Governance in Managing Common Pool Resources Case Study: Collaborative Planning to manage Thematic Parks in Bandung City, Indonesia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 227, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rini, A.; Setiyorini, H.P.; Diyah. A Comparative Study of Both the Local Community and Tourists’ Perceptions Concerning the Development of Thematic Parks in City Setting. Man. India 2016, 22, 225–245. [Google Scholar]

- Paryudi; Probosari, N.; Ardhanariswari, K.A. Analysis of the Development of Bandung as Creative City. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2017, 8, 1025–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Hermawati, R.; Runiawati, N. Enhancement of Creative Industries in Bandung City through Cultural, Community, and Public Policy Approach. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Law, Education, and Humanities (ICLEH’15), Paris, France, 25–26 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marhani, T.A. Strengthening the Identity of Tourism Destination in Bandung City with City Branding. Int. J. Dev. Res. 2017, 7, 17692–17698. [Google Scholar]

- Kasapi, I.; Cela, A. Destination Branding: A Review of the City Branding Literature. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 8, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.; Rowlwy, J. An Analysis of terminology used in place branding. Place Brand. Pub. Dipl. 2008, 4, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.V. Selling Places: The Marketing and Promotion of Towns and Cities 1850–2000; E & FN Spon: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Asplund, C.; Rein, I.; Heider, D. Marketing Places Europe: Attracting Investments, Industries, Residents and Visitors to European Cities, Communities, Regions and Nations; Pearson Education Ltd.: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Setiati, G. Pengaruh Pengguna, Tempat dan Proses terhadap Place Attachment pada Coffe Shop di Bandung. Master’s Thesis, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Bandung, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, I.; Low, S.M. (Eds.) Place Attachment, Human Behavior and Environment; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cuba, L.; Hummon, D.M. A Place to Call Home: Identification with Dwelling, Community, and Region. Soc. Q. 1993, 34, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Roggenbuck, J.W. Measuring Place Attachment: Some Preliminary Result. In Abstracts: 1989 Leisure Research Symposium; National Recreation and Park Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 1989; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, N.F.; Cohen, S.A.; Scarles, C. The Power of Social Media Storytelling in Destination Branding. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Ha, C.; Lee, H.C. Redesign In-Flight Service with Service Blueprint Based on Text Analysis. J. Sustain. 2018, 10, 4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbaika, D.R. The Effective of Social Media in Destination Branding. Bachelor’s Thesis, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Nethelands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pecar, S. Towards opinion Summarization of Customer Reviews. In Proceedings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Vidusi; Gurjot, S.S. Sentiment Mining of Online Reviews Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Int. J. Eng. Dev. Res. 2017, 5, 1321–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Divyasharee, N.; Kumar K L, S.; Majumdar, J. Opinion Mining and Sentiment Analysis of TripAdvisor.in for Hotel Reviews. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2017, 4, 1462–1467. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.C.; Chi, Y.C.; Hsin, P.L. Constructing Patent Maps Using Text Mining to Sustainably Detect Potential Technologies Opportunities. J. Sustain. 2018, 10, 3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BAPPEDA Kota Bandung; Interplan, P.T.; Belaputra. Laporan Akhir Kajian Konsep Pengembangan dan Pengelolaan Taman Kota Menjadi Taman Tematik di Kota Bandung; BAPPEDA Kota Bandung: Bandung, Indonesia, 2014.

- Sinarta, F. Identifying Creative Urban Landscape towards Creative Tourism in Bandung: A Preliminary Study. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Landscape Development, Bogor, Indonesia, 9–10 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nururohmaha, Z. Shared-power Governance in Managing Common Pool Resources Case Study: Collaborative Planning to Manage Thematic Parks in Bandung City. In Proceedings of the International Conference, Intelligent Planning towards Smart Cities, CITIES 2015, Surabaya, Indonesia, 3–4 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Indrawan, H. Tema dan Gaya Desain dalam Perancangan Interior Hotel. Master’s Thesis, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Bandung, Indonesia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ilmiajayanti, F.; Dewi, D.I.K. Persepsi Pengguna Taman Tematik Kota Bandung terhadap Aksesibilitas dan Pemanfaatannya. J. RUANG 2015, 1, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kemperman, A.D.A.M. Temporal Aspects of Theme Park Choice Behavior: Modeling Variety Seeking, Seasonality and Diversification to Support Theme Park Planning. Ph.D. Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, S.A.; Aminudin, N.; Rahman, N.A. Visitors’ Experiences of Cluster Development at Thematic Parks in Malaysia. Asian Soc. Sci. 2017, 13, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajmirsadeghi, R.S.; Shamsuddin, S.; Foroughi, A. The Impact of Physical Design Factor on the Effective Use of Public Squares. Int. J. Fundam. Psychol. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rainisto, S.K. Success Factors of Place Marketing: A Study of Place Marketing Practices in Northern Europe and the United States. Ph.D. Thesis, Helsinki University of Technology, Helsinki, Finland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D. Managing Brand Equity; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, S. Destination brand positions of a competitive set of near-home destinations. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarelli, A.; Brorstrom, S. Problematising Place Branding Research: A Meta-Theorretical of the Literature. Mark. Rev. 2013, 13, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastaman, A. Bandung City Branding: Exploring the Role of Local Community Involvement to Gain City Competitive Value. J. Entrep. Bus. Econ. 2018, 6, 144–165. [Google Scholar]

- Sherer, P.M. The Benefits of Parks. The trust for Public Land; The Trust for Public Land: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fok, K.W.K.; Law, W.W.Y. City Re-Imagined: Multi-stakeholder study on Branding Hong Kong as a City of Greenery. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 1039–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, M.; Bokic, M. Destination Branding: A Case Study of National Park in Montenegro. In Proceedings of the SITCON 2016, Quality as a Basis for Tourism Destination Competitiveness, Belgrade, Serbia, 30 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Ashworth, G.J. City Branding: An Effective of Identity or a Transitory Marketing Trick. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2015, 96, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Azam, S.; Kanti, T.B. Factors Affecting the Selection of Tour Destination in Bangladesh: An Empirical Analysis. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, B.T. Managing Customer Value; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Central of Bureau Statistic. Available online: http://sp2010.bps.go.id (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Dinnie, S. City Branding: Theory and Cases; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ervina, E.; Octaviany, V. Visitor Behavior at Theme Parks as an Urban Tourism in the City of Bandung, Indonesia. J. Bus. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 2, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housing and Settlement Area Office Land and Parks in Bandung City. Available online: http://dpkp3.bandung.go.i (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Comparison of Local Review Sites. Available online: https://www.brightlocal.com (accessed on 17 October 2018).

- Khairullah, K.; Barum, B.; Aurnagzeb, K.; Ashraf, U. Mining Opinions Components from Unstructured Reviews. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2014, 26, 258–275. [Google Scholar]

- Shelly, G.; Shubhangi, J.; Shivani, G. Opinion Mining for Hotel Rating through Reviews Using Decision Tree Classification Method. Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Sci. 2018, 9, 180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkelund, E.; Burnett, T.H.; Norvag, K. A Study of Opinion Mining and Visualization of Hotel Reviews. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Information Integration and Web-based Applications & Services, Bali, Indonesia, 3–5 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Perikos, I.; Kovas, K.; Grivokostopoulou, F.; Hatzilygeroudis, I. A System for Aspect-based Opinion Mining of Hotel Reviews. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST), Porto, Portugal, 25–27 April 2017; pp. 388–394. [Google Scholar]

- Grefenstette, G.; Tapanainen, P. What is a Word, What is a Sentence? Problem of Tokenization; Rank Xerox Research Center, Grenoble Laboratory: Grenoble, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, F.M. Introduction English Linguistics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, H.; Sian, K.N.; Srinivas, R.K. Rating Lead You to the Product, Reviews Help you Clinch it? The Dynamics and impact of Online Reviews Sentiment on Product Sales. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 57, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Chistoper, D.M.; Schutze, H. Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1999; pp. 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Salton, G.; Buckley, C. Term-weighting approaches in Automatic text retrieval. Inf. Process. Manag. 1988, 24, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-J.; Ohk, K.; Moon, C.-S. Trend Analysis by Using Text Mining of Journal Regarding Consumer Policy. New Phys. Sae Mulli 2017, 67, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Score Rating for Local Places. Available online: http: //support.google.com (accessed on 10 September 2018).

| No | Name of Thematic Park | Area (m2) | District | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Superhero Park | 2051 | Sumur Bandung | There are several statues of famous superheroes. This park uses superhero statues as thematic icons. |

| 2 | Musik Centrum Park | 2100 | Sumur Bandung | The goal of Musik Centrum Park is to provide a place for residents, especially the youth, to practice or perform music, art, and sport. |

| 3 | Foto Park | 3610 | Sumur Bandung | Foto Park is intended to accommodate photography lovers. In this park, there are several works of photography. |

| 4 | Gesit Park | 755 | Coblong | Gesit Park or Agile park is designed with green and active concepts. The green concept is displayed by a green garden area, while the active concept includes a play area including various sports games. |

| 5 | Fitness Park | 4073 | Coblong | Fitness Park is one of the thematic parks built by the Bandung city government to revitalize the area and provide sports facilities to the public. In accordance with the theme, Fitness Park was specifically designed for outdoor exercise. |

| 6 | Jomblo Park | 1539 | Coblong | Taman Pasupati, better known as Taman Jomblo, is located under the Pasupati bridge. A single person or “jomblo” (in Indonesian terms) is someone who is not in a relationship or is “unmarried”. The term “Taman Jomblo” is represented by the presence of a seat in that park that is shaped like a colorful cube with a small size that only fits one person. |

| 7 | Film Park | 1100 | Bandung Wetan | This park is a place of appreciation for Indonesian films. Residents can watch movies from the 4 × 8 m Videotron screen with an electrical power of up to 33,000 watts. In accordance with the theme, this park was specifically designed for people to watch films produced by filmmakers from Bandung and also the community. |

| 8 | Lansia Park | 16,257 | Bandung Wetan | Lansia is an abbreviation of Lanjut Usia or “elderly”. Lansia Park is a park for the elderly who want to refresh themselves or exercise. Despite its name, the park is visited by individuals of all ages from Bandung or from outside the city of Bandung. |

| 9 | Pet park | 6085 | Bandung Wetan | Animal Park provides a playground for animal lovers and their pets. This park was prepared for the community and animal lovers. |

| 10 | Inklusi park | 2111 | Bandung Wetan | Inklusi Park was developed for disabled people. Inklusi Park is a public facility that was built as part of the effort to reduce discrimination in the city of Bandung. This park is designed to provide a space for disabled individuals to move around and socialize, and it has become a place of healing therapy. |

| No | Name of Park | Area (m2) | Location | District |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maluku Park | 24,023 | Jl. Ambon | Sumur Bandung |

| 2 | Kosambi Park | 759 | Jl. Kosambi | Sumur Bandung |

| 3 | Riau Park | 685 | Jl. Riau | Sumur Bandung |

| 4 | Buton Park | 612 | Jl. Buton | Sumur Bandung |

| 5 | Nias Park | 310 | Jl. Nias | Sumur Bandung |

| 6 | Ganesha Park | 9612 | Jl. Ganesha | Coblong |

| 7 | Panatayuda Park | 2387 | Jl. Panatayuda | Coblong |

| 8 | Bagusrangin Park | 1560 | Jl. Bagusrangin | Coblong |

| 9 | Gelap Nyawan Park | 1656 | Jl. Gelap Nyawan | Coblong |

| 10 | Dayang Sumbi Park | 754 | Jl. Dayang Sumbi | Coblong |

| 11 | Gasibu Park | 25,962 | Jl. Gasibu | Bandung Wetan |

| 12 | Gempol Park | 1245 | Jl. Gempol | Bandung Wetan |

| 13 | Citarum Park | 1102 | Jl. Citarum | Bandung Wetan |

| 14 | Nyland Park | 783 | Jl. Nyland | Bandung Wetan |

| 15 | Cipunagara Park | 688 | Jl. Cipunagara | Bandung Wetan |

| Thematic Parks | Summary of Visitors’ Perceptions |

|---|---|

| Superhero Park | Superhero Park is a place or park that is described as good, suitable, and comfortable for children and families. It has a playground, superhero statues, and free Wi-Fi facilities. |

| Musik Centrum Park | Musik Centrum Park is described as good, cool, nice, comfortable, shady, and suitable for children to play in. It is a musical community where people practice music. |

| Foto Park | Foto Park is a place that is described as nice, good, comfortable, and suitable for families and kids. It has free Wi-Fi and a playground that can be used to play on and take photos. |

| Gesit Park | Gesit Park is a good place that is described as nice, comfortable, small, and suitable for children. It has a playground and free Wi-Fi facilities. It is described as needing maintenance |

| Fitness Park | Fitness Park is a place that is described as nice, with free Wi-Fi and gym equipment, that is shady and is good for sports and jogging. |

| Jomblo Park | Jomblo Park is a good place that is described as nice, unique, and comfortable for young people and single people, with a space for skateboarding, but it is also crowded and noisy. |

| Film Park | Film Park is described as good, cool, nice, comfortable, and suitable for families, children, and the community. It has screen facilities for gathering and watching films or movies, and it has free Wi-Fi facilities. |

| Lansia Park | Lansia Park is a park in Bandung city that is described as good, nice, comfortable, shady, clean, and beautiful. It is suitable for families, children, and for jogging and sports. |

| Pet Park | Pet Park is a good place that is described as nice and comfortable. It is a suitable place for animal lovers to bring pets to and to gather in. It has free Wi-Fi. |

| Inklusi Park | Inklusi Park is a park in Bandung city that is described as cool, clean, and comfortable for families, children, and disabled people. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Munawir; Koerniawan, M.D.; Dewancker, B.J. Visitor Perceptions and Effectiveness of Place Branding Strategies in Thematic Parks in Bandung City Using Text Mining Based on Google Maps User Reviews. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072123

Munawir, Koerniawan MD, Dewancker BJ. Visitor Perceptions and Effectiveness of Place Branding Strategies in Thematic Parks in Bandung City Using Text Mining Based on Google Maps User Reviews. Sustainability. 2019; 11(7):2123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072123

Chicago/Turabian StyleMunawir, Mochamad Donny Koerniawan, and Bart Julien Dewancker. 2019. "Visitor Perceptions and Effectiveness of Place Branding Strategies in Thematic Parks in Bandung City Using Text Mining Based on Google Maps User Reviews" Sustainability 11, no. 7: 2123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072123

APA StyleMunawir, Koerniawan, M. D., & Dewancker, B. J. (2019). Visitor Perceptions and Effectiveness of Place Branding Strategies in Thematic Parks in Bandung City Using Text Mining Based on Google Maps User Reviews. Sustainability, 11(7), 2123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072123