Measuring the Efficiency of Public and Private Delivery Forms: An Application to the Waste Collection Service Using Order-M Data Panel Frontier Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. Method

- For a given level of , a random sub-sample of size m is created with replacement between the that meet the condition ≥ .

- The efficiency coefficient is estimated from this random sub-sample and the resolution of non-convex algorithms of FDH data panel programming.

- These two steps are repeated B times, estimating a FDH data panel coefficient of efficiency in each round, so that by the end of the process B efficiency coefficients have been obtained, ( = 1, 2, …, ).

- Finally, a central value (the arithmetic mean) of the B efficiency coefficients is estimated as:

3.2. Data

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sjöström, M.; Östblom, G. Decoupling waste generation from economic growth—A CGE analysis of the Swedish case. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1545–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plata-Díaz, A.M.; Zafra-Gómez, J.L.; Pérez-López, G.; López-Hernández, A.M. Alternative management structures for municipal waste collection services: The influence of economic and political factors. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrate, G.; Boffa, F.; Erbetta, F.; Vannoni, D. Voters’ Information, Corruption, and the Efficiency of Local Public Services. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, F. Environmental impacts of post-consumer material managements: Recycling, biological treatments, incineration. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 2354–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Li, X.; Cui, Z. Life cycle assessment of four municipal solid waste management scenarios in China. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 2362–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovea, M.D.; Ibáñez-Forés, V.; Gallardo, A.; Colomer-Mendoza, F.J. Environmental assessment of alternative municipal solid waste management strategies. A Spanish case study. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 2383–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, A.; Carvalho, P.; Romano, G.; Marques, R.C.; Leardini, C. Assessing efficiency drivers in municipal solid waste collection services through a non-parametric method. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-López, B.; Moreno-Enguix, M.R.; Solana-Ibañez, J. Determinants of efficiency in the provision of municipal street-cleaning and refuse collection services. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bel, G.; Warner, M. Does privatization of solid waste and water services reduce costs? A review of empirical studies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 52, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, N.; Pedraja, F.; Suárez-Pandiello, J. Measuring the efficiency of Spanish municipal refuse collection services. Local Gov. Stud. 2000, 26, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, P.; Marques, R.C. On the economic performance of the waste sector. A literature review. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 106, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Maier, S.; Horn, R.; Holländer, R.; Aschemann, R. Development of an Ex-Ante Sustainability Assessment Methodology for Municipal Solid Waste Management Innovations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.A.; Maas, G.; Hogland, W. Solid waste management challenges for cities in developing countries. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, N.; De Jaeger, S. Measuring and explaining the cost efficiency of municipal solid waste collection and processing services. Omega 2013, 41, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Warner, M.E. Inter-municipal cooperation and costs: Expectations and evidence. Public Adm. 2015, 93, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, A.C.; Dollery, B.E. Measuring efficiency in local government: An analysis of New South Wales municipalities’ domestic waste management function. Policy Stud. J. 2001, 29, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, A.; Kulshrestha, M.; Kulshreshtha, M. Efficiency evaluation of municipal solid waste management utilities in the urban cities of the state of Madhya Pradesh, India, using stochastic frontier analysis. Benchmarking Int. J. 2012, 19, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, R.; Buysse, J.; Gellynck, X. Cost comparison between private and public collection of residual household waste: Multiple case studies in the Flemish region of Belgium. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, G.; Allegrini, M.; Del Lungo, C.; Savellini, P.G.; Gabellini, L. Drivers of solid waste collection costs. Empirical evidence from Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDavid, J.C. Solid-waste contracting-out, competition, and bidding practices among Canadian local governments. Can. Public Adm. 2001, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Mur, M. Intermunicipal cooperation, privatization and waste management costs: Evidence from rural municipalities. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 2772–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.; Lobina, E.; Terhorst, P. Re-municipalisation in the early twenty-first century: Water in France and energy in Germany. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2013, 27, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradus, R.; Budding, T. Political and institutional explanations for increasing re-municipalization. Urban Aff. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Gradus, R. Privatisation, contracting-out and inter-municipal cooperation: New developments in local public service delivery. Local Gov. Stud. 2018, 44, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máñez, J.; Pérez-López, G.; Prior, D.; Zafra-Gómez, J.L. Understanding the dynamic effect of contracting out on the delivery of local public services. Reg. Stud. 2016, 50, 2069–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, G.; Prior, D.; Zafra-Gómez, J.L.; Plata-Díaz, A.M. Cost efficiency in municipal solid waste service delivery. Alternative management forms in relation to local population size. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 255, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Rodríguez, J.C.; Pérez-López, G.; Zafra-Gómez, J.L.; Prior, D. Estimación de la eficiencia a largo plazo en servicios públicos locales mediante fronteras robustas con datos de panel. Hacienda Pública Española 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stastna, L.; Gregor, M. Local Government Efficiency: Evidence from the Czech Municipalities. IES Working Paper No. 14/2011. 2011. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1978730 (accessed on 16 May 2018). [CrossRef]

- Da Cruz, N.F.; Marques, R.C. Revisiting the determinants of local government performance. Omega 2014, 44, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, G.; Prior, D.; Zafra-Gómez, J.L. Rethinking new public management delivery forms and efficiency: Long-term effects in Spanish local government. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2015, 25, 1157–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narbón-Perpiñá, I.; De Witte, K. Local governments’ efficiency: A systematic literature review—Part I. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2018, 25, 431–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.; Entwistle, T. Four faces of public service efficiency: What, how, when and for whom to produce. Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlaftis, M.G.; Tsamboulas, D. Efficiency measurement in public transport: Are findings specification sensitive? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2012, 46, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyne, G.A. Public and private management: what’s the difference? J. Manag. Stud. 2002, 39, 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, E.; Federico, A.; Musmeci, F. A system oriented integrated indicator for sustainable development in Italy. Ecol. Indic. 2002, 2, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Fageda, X. Why do local governments privatise public services? A survey of empirical studies. Local Gov. Stud. 2007, 33, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, P.; Cruz, N.F.; Marques, R.C. The performance of private partners in the waste sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 29, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, C. A public management for all seasons? Public Adm. 1991, 69, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, C. The “New Public Management” in the 1980s: Variations on a theme. Account. Organ. Soc. 1995, 20, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefenbach, T. New public management in public sector organizations: The dark sides of managerialistic ‘enlightenment’. Public Adm. 2009, 87, 892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cruz, N.F.; Marques, R.C. Mixed companies and local governance: No man can serve two masters. Public Adm. 2012, 90, 737–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.; Van de Walle, S. New public management and citizens’ perceptions of local service efficiency, responsiveness, equity and effectiveness. Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 762–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, C.; Dixon, R. A model of cost-cutting in government? The great management revolution in UK central government reconsidered. Public Adm. 2013, 91, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettl, D. The Global Public Management Revolution: A Report on the Transformation of Governance; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Niskanen, W.A. Bureaucracy and Representative Government; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Savas, E.S. Privatization. The Key to Better Government; Chatham House: Chatham, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Shleifer, A. State versus Private Ownership. J. Econ. Perspect. 1998, 12, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, I.M.G. La nueva gestión pública: Evolución y tendencias. Presupuesto y Gasto Público 2007, 47, 37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, T.; Lægreid, P. Complexity and hybrid public administration-theoretical and empirical challenges. Public Organ. Rev. 2011, 11, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, J.; Yarrow, G. Economic perspectives on privatization. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, M.E.; Bel, G. Competition or monopoly? Comparing privatization of local public services in the US and Spain. Public Adm. 2008, 86, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Hernández, A.M.; Zafra-Gómez, J.L.; Plata-Díaz, A.M.; de la Higuera-Molina, E.J. Modelling fiscal stress and contracting out in local government: The influence of time, financial condition, and the great recession. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. Economics of the Public Sector; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Savas, E.S.; Savas, E.S. Privatization and Public? Private Partnerships; Chatham House: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Swarts, D.; Warner, M.E. Hybrid firms and transit delivery: The case of Berlin. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2014, 85, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannadi, J.; Dollery, B. An evaluation of private sector provision of public infrastructure in Australian local government. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2005, 64, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, W.; Yvrande-Billon, A. Ownership, contractual practices and technical efficiency: The case of urban public transport in France. J. Transp. Econ. Policy 2007, 41, 257–282. [Google Scholar]

- Bel, G.; Fageda, X. Between privatization and intermunicipal cooperation: Small municipalities, scale economies and transaction costs. Urban Public Econ. Rev. 2006, 6, 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue, J.D. The Privatization Decision. Public Ends, Private Means; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, M.; Hefetz, A. Rural—Urban differences in privatization: Limits to the competitive state. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2003, 21, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Costas, A. Do public sector reforms get rusty? Local privatization in Spain. J. Policy Reform 2006, 9, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.L.; Potoski, M. Transaction costs and contracting: The practitioner perspective. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2005, 28, 326–351. [Google Scholar]

- Bel, G.; Fageda, X.; Mur, M. Does cooperation reduce service delivery costs? Evidence from residential solid waste services. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 24, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollery, B.; Byrnes, J.; Crase, L. Is bigger better? Local government amalgamation and the South Australian rising to the challenge inquiry. Econ. Anal. Policy 2007, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, L.J., Jr.; Meier, K.J. Parkinson’s Law and the New Public Management? Contracting Determinants and Service-Quality Consequences in Public Education. Public Adm. Rev. 2004, 64, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, M.E.; Hefetz, A. Insourcing and outsourcing: The dynamics of privatization among US municipalities 2002–2007. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2012, 78, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouwen, A.; Rietveld, P. Does competitive tendering improve customer satisfaction with public transport? A case study for the Netherlands. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2013, 51, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Fageda, X. Empirical analysis of solid management waste costs: Some evidence from Galicia, Spain. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hirschhausen, C.; Cullmann, A. A nonparametric efficiency analysis of German public transport companies. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2010, 46, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraio, C.; Diana, M.; Di Costa, F.; Leporelli, C.; Matteucci, G.; Nastasi, A. Efficiency and effectiveness in the urban public transport sector: A critical review with directions for future research. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 248, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, J.E. Public Administration & Public Management: The Principal-Agent Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.L.; Potoski, M. Transaction costs and institutional explanations for government service production decisions. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2003, 13, 441–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, M.E.; Hefetz, A. Managing markets for public service: The role of mixed public–private delivery of city services. Public Adm. Rev. 2008, 68, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestana Barros, C.; Peypoch, N. Productivity changes in Portuguese bus companies. Transp. Policy 2010, 17, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalate, D.; Bel, G.; Calzada, J. Governance and regulation of urban bus transportation: Using partial privatization to achieve the better of two worlds. Regul. Gov. 2012, 6, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saal, D.S.; Parker, D. Productivity and price performance in the privatized water and sewerage companies of England and Wales. J. Regul. Econ. 2001, 20, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, E.; Barrow, M. The impact of contracting out on the costs of refuse collection services: The case of Ireland. Econ. Soc. Rev. 2000, 31, 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkgraaf, E.; Gradus, R.; Melenberg, B. Contracting out refuse collection. Empir. Econ. 2003, 28, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, H. Ownership and production costs: Choosing between public production and contracting-out in the case of Swedish refuse collection. Fisc. Stud. 2003, 24, 451–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkgraaf, E.; Gradus, R. Cost savings in unit-based pricing of household waste: The case of the Netherlands. Resour. Energy Econ. 2004, 26, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, G.; Fageda, X.; Warner, M.E. Is private production of public services cheaper than public production? A meta-regression analysis of solid waste and water services. J. Pol. Anal. Manage. 2010, 29, 553–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, J.S.; Harrington, W.; Pizer, W.A.; Gillingham, K. Economies of scale in community water systems. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 2006, 98, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafra-Gómez, J.L.; Prior, D.; Plata-Díaz, A.M.; López-Hernández, A.M. Reducing costs in times of crisis: Delivery forms in small and medium sized local governments’ waste management services. Public Adm. 2013, 91, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Brandli, L.; Moora, H.; Kruopienė, J.; Stenmarck, Å. Benchmarking approaches and methods in the field of urban waste management. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 4377–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surroca, J.; Prior, D.; Tribó Giné, J.A. Using panel data DEA to measure CEOs’ focus of attention: An application to the study of cognitive group membership and performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 370–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, G.; Prior, D.; Zafra-Gómez, J.L. Temporal scale efficiency in DEA panel data estimations. An application to the solid waste disposal service in Spain. Omega 2018, 76, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Clark, C.T.; Cooper, W.W.; Golany, B. A developmental study of data envelopment analysis in measuring the efficiency of maintenance units in the US air forces. Ann. Oper. Res. 1984, 2, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulkens, H.; Eeckaut, P.V. Non-parametric efficiency, progress and regress measures for panel data: Methodological aspects. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1995, 80, 474–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinane, K.; Wang, T. The efficiency analysis of container port production using DEA panel data approaches. OR Spectr. 2010, 32, 717–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simar, L.; Wilson, P.W. Statistical inference in nonparametric frontier models: Recent developments and perspectives. In The Measurement of Productive Efficiency and Productivity Growth, 2nd ed.; Fried, H.O., Lovell, C.A.K., Schmidt, S.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 421–521. [Google Scholar]

- Daraio, C.; Simar, L. Advanced Robust and Nonparametric Methods in Efficiency Analysis: Methodology and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cherchye, L.; Demuynck, T.; De Rock, B.; De Witte, K. Nonparametric analysis of multi-output production with joint inputs. Econ. J. 2014, 124, 735–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer-Coll, M.T.; Prior, D.; Tortosa-Ausina, E. Decentralization and efficiency of local government. Ann. Reg. Stud. 2010, 45, 571–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, K.; Geys, B. Citizen coproduction and efficient public good provision: Theory and evidence from local public libraries. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 224, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, P.; De Witte, K.; Marques, R.C. Regulatory structures and operational environment in the Portuguese waste sector. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; R Development Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2011; ISBN 3-900051-07-0. Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 March 2018).

- Wilson, P. FEAR: Frontier Efficiency Analysis with R; University of Clemson: Clemson, SC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. Nonparametric testing of closeness between two unknown distribution functions. Econom. Rev. 1996, 15, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simar, L.; Zelenyuk, V. On testing equality of distributions of technical efficiency scores. Econom. Rev. 2006, 25, 497–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, J.M.; Tortosa-Ausina, E. Social capital and bank performance: An international comparison for OECD countries. Manch. Sch. 2008, 76, 223–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer-Coll, M.T.; Prior, D. Short-and long-term evaluation of efficiency and quality. An application to Spanish municipalities. Appl. Econ. 2009, 41, 2991–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, D.; Martín-Pinillos, I.; Pérez-López, G.; Zafra-Gómez, J.L. Cost efficiency and financial situation of local governments in the Canary Isles during the recession. Revista de Contabilidad-Spanish Account. Rev. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Balaguer-Coll, M.T.; Ivanova-Toneva, M. La importancia de los efectos espaciales en la deuda municipal. Revista de Contabilidad-Spanish Account. Rev. 2019, 22, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Boin, A.; Keller, A. Managing transboundary crises: Identifying the building blocks of an effective response system. J. Conting Crisis Manag. 2010, 18, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Public Delivery | Population | Variable | Mean | Min | Max | Std. Dev. |

| 1000–5000 inhabitants | Cost (euro) | 417,974 | 66,349 | 833,197 | 234,896 | |

| Tonnes | 4597 | 355 | 19,016 | 5781 | ||

| Tonnes * Quality | 8980 | 711 | 37,311 | 11,344 | ||

| Containers | 338 | 81 | 583 | 201 | ||

| Population | Variable | Mean | Min | Max | Std. Dev. | |

| 5000–20,000 inhabitants | Cost (euro) | 445,389 | 68,266 | 2,115,041 | 310,963 | |

| Tonnes | 4438 | 703 | 19,016 | 3862 | ||

| Tonnes * Quality | 8586 | 1406 | 37,311 | 7663 | ||

| Containers | 504 | 85 | 1299 | 272 | ||

| Population | Variable | Mean | Min | Max | Std. Dev. | |

| 20,000–50,000 inhabitants | Cost (euro) | 962,845 | 300,000 | 1,918,332 | 445,641 | |

| Tonnes | 9064 | 4574 | 19,016 | 5922 | ||

| Tonnes * Quality | 17,815 | 8943 | 37,311 | 11,631 | ||

| Containers | 677 | 250 | 1273 | 188 | ||

| Private Delivery | Population | Variable | Mean | Min | Max | Std. Dev. |

| 1000–5000 inhabitants | Cost (euro) | 544,504 | 60,974 | 1,361,950 | 390,499 | |

| Tonnes | 8044 | 1174 | 20,920 | 7258 | ||

| Tonnes * Quality | 15,253 | 1385 | 39,203 | 13,388 | ||

| Containers | 273 | 28 | 488 | 157 | ||

| Population | Variable | Mean | Min | Max | Std. Dev. | |

| 5000–20,000 inhabitants | Cost (euro) | 719,414 | 58,423 | 2,865,224 | 539,759 | |

| Tonnes | 5598 | 1268 | 20,920 | 3779 | ||

| Tonnes * Quality | 10,716 | 2537 | 39,203 | 7301 | ||

| Containers | 340 | 21 | 1467 | 220 | ||

| Population | Variable | Mean | Min | Max | Std. Dev. | |

| 20,000–50,000 inhabitants | Cost (euro) | 1,330,167 | 183,649 | 3,530,963 | 578,238 | |

| Tonnes | 11,820 | 1255 | 20,920 | 4718 | ||

| Tonnes * Quality | 22,945 | 2510 | 39,203 | 8648 | ||

| Containers | 636 | 61 | 3101 | 523 |

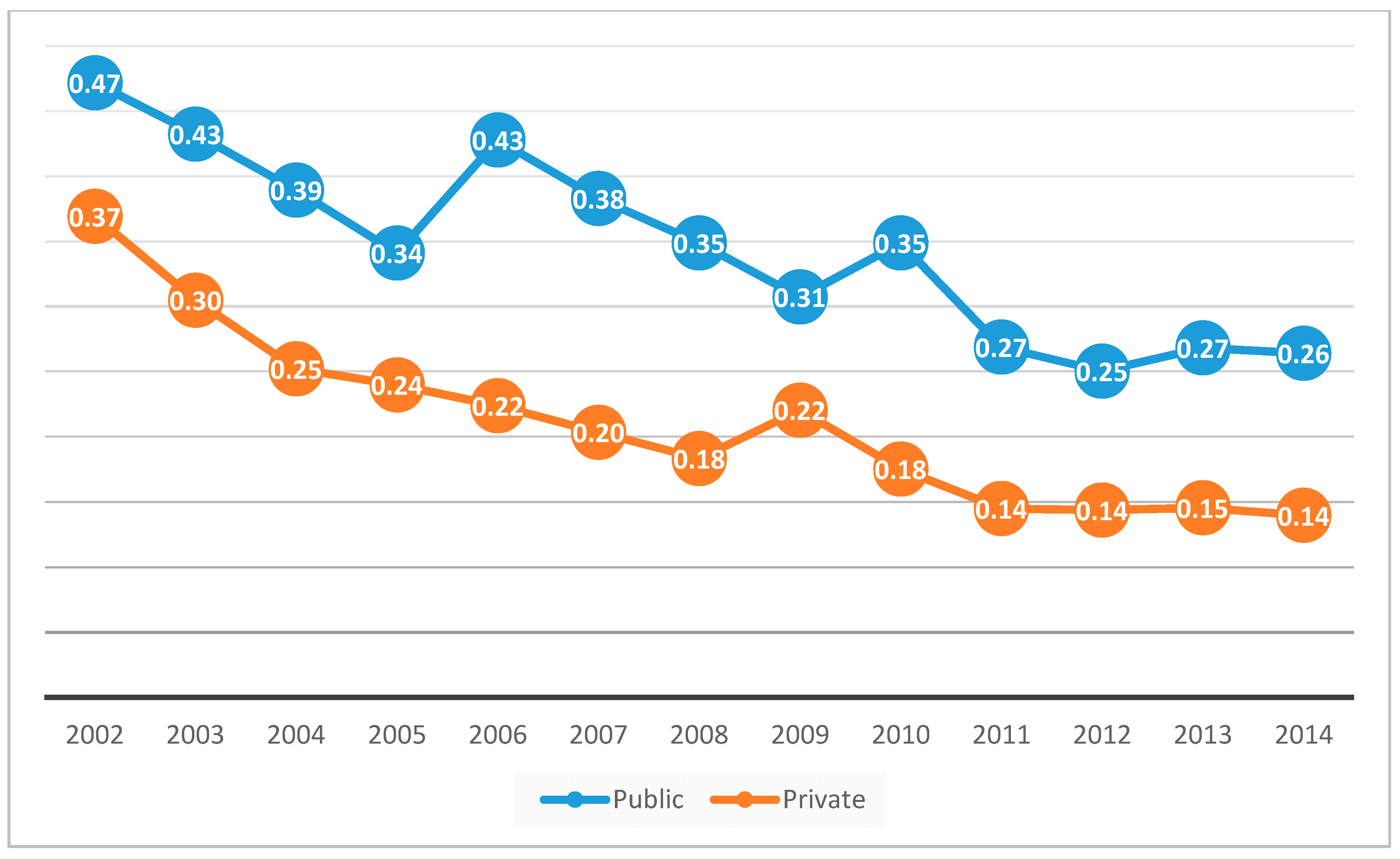

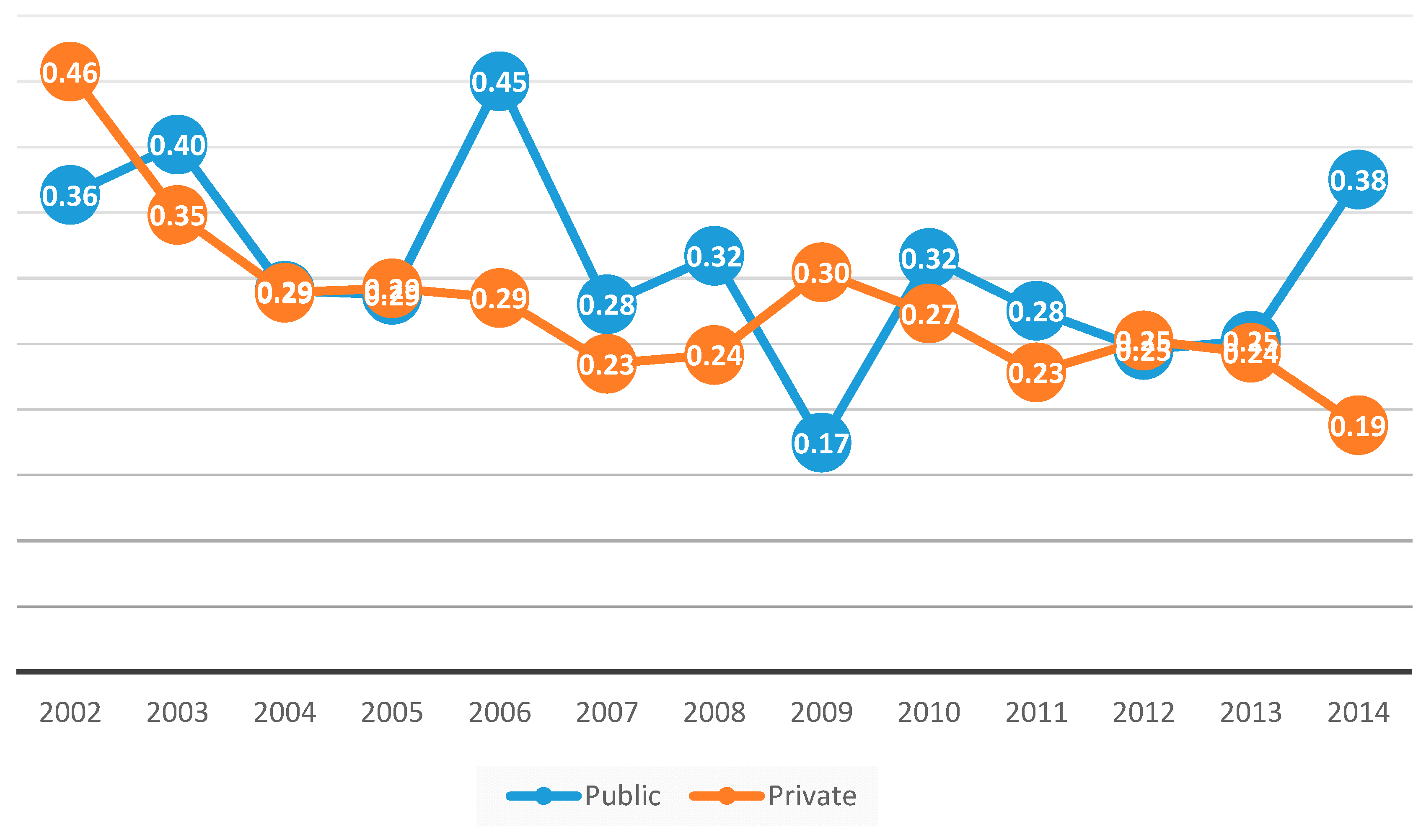

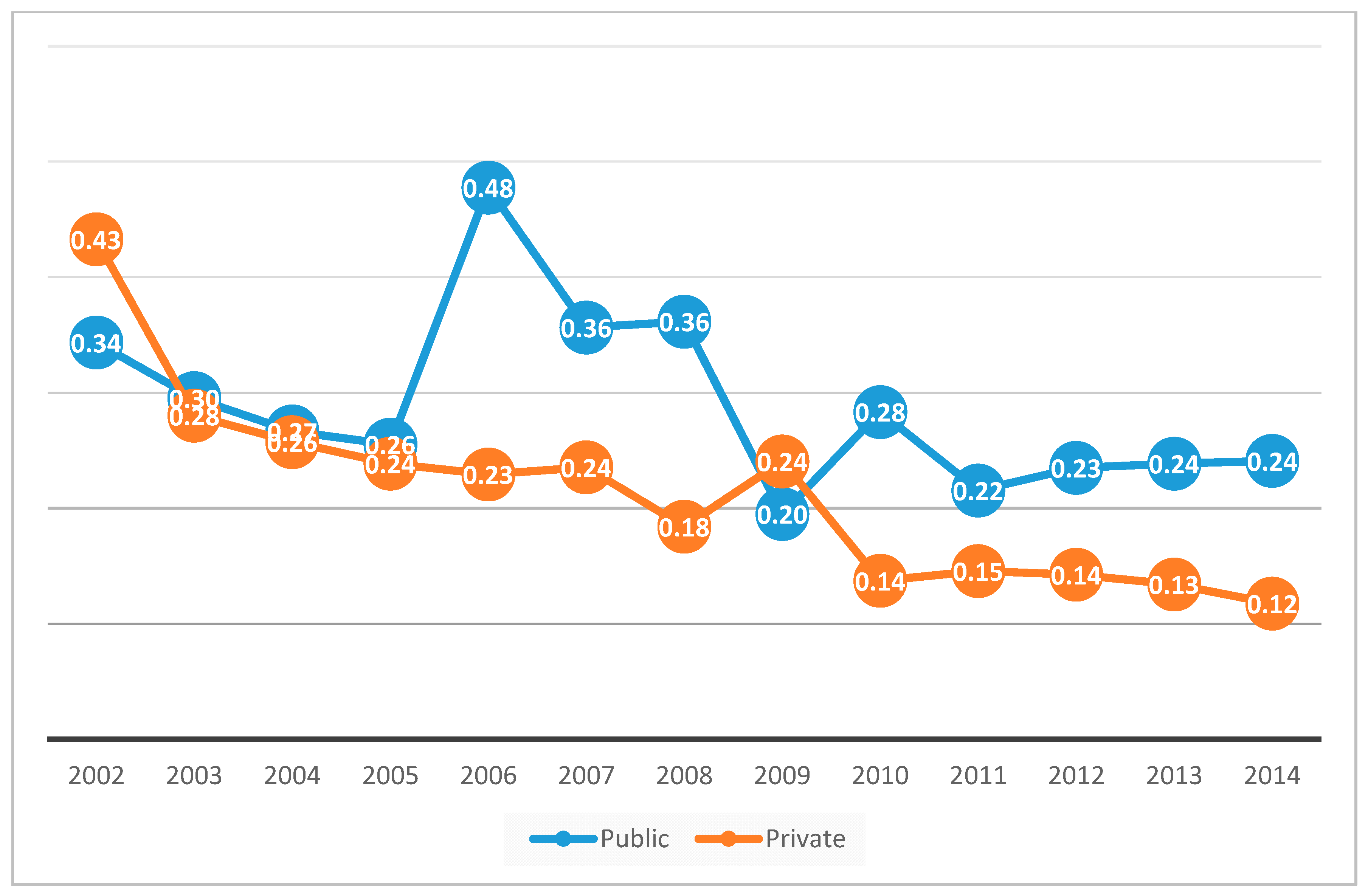

| Year | Mean | Median | Min. | Max. | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 0.471 | 0.469 | 0.096 | 1 | 0.246 |

| 2003 | 0.432 | 0.421 | 0.067 | 1 | 0.234 |

| 2004 | 0.389 | 0.363 | 0.062 | 1 | 0.241 |

| 2005 | 0.340 | 0.311 | 0.061 | 0.902 | 0.210 |

| 2006 | 0.427 | 0.385 | 0.084 | 1 | 0.278 |

| 2007 | 0.382 | 0.346 | 0.055 | 0.965 | 0.234 |

| 2008 | 0.348 | 0.314 | 0.068 | 0.890 | 0.212 |

| 2009 | 0.307 | 0.261 | 0.065 | 1 | 0.205 |

| 2010 | 0.348 | 0.289 | 0.057 | 1 | 0.229 |

| 2011 | 0.268 | 0.231 | 0.053 | 1 | 0.209 |

| 2012 | 0.250 | 0.208 | 0.053 | 0.995 | 0.179 |

| 2013 | 0.268 | 0.171 | 0.052 | 1 | 0.222 |

| 2014 | 0.264 | 0.173 | 0.043 | 1.001 | 0.238 |

| Year | Mean | Median | Min. | Max. | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 0.369 | 0.271 | 0.055 | 1.025 | 0.291 |

| 2003 | 0.304 | 0.216 | 0.052 | 1 | 0.245 |

| 2004 | 0.252 | 0.179 | 0.038 | 0.931 | 0.203 |

| 2005 | 0.239 | 0.149 | 0.033 | 1 | 0.212 |

| 2006 | 0.223 | 0.179 | 0.039 | 1 | 0.172 |

| 2007 | 0.203 | 0.143 | 0.032 | 1 | 0.181 |

| 2008 | 0.183 | 0.166 | 0.020 | 0.693 | 0.141 |

| 2009 | 0.220 | 0.157 | 0.030 | 1 | 0.227 |

| 2010 | 0.175 | 0.137 | 0.022 | 1 | 0.173 |

| 2011 | 0.144 | 0.122 | 0.030 | 0.604 | 0.102 |

| 2012 | 0.143 | 0.108 | 0.018 | 0.912 | 0.139 |

| 2013 | 0.145 | 0.122 | 0.026 | 1.001 | 0.127 |

| 2014 | 0.139 | 0.115 | 0.024 | 0.765 | 0.102 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campos-Alba, C.M.; De la Higuera-Molina, E.J.; Pérez-López, G.; Zafra-Gómez, J.L. Measuring the Efficiency of Public and Private Delivery Forms: An Application to the Waste Collection Service Using Order-M Data Panel Frontier Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2056. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072056

Campos-Alba CM, De la Higuera-Molina EJ, Pérez-López G, Zafra-Gómez JL. Measuring the Efficiency of Public and Private Delivery Forms: An Application to the Waste Collection Service Using Order-M Data Panel Frontier Analysis. Sustainability. 2019; 11(7):2056. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072056

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampos-Alba, Cristina M., Emilio J. De la Higuera-Molina, Gemma Pérez-López, and José L. Zafra-Gómez. 2019. "Measuring the Efficiency of Public and Private Delivery Forms: An Application to the Waste Collection Service Using Order-M Data Panel Frontier Analysis" Sustainability 11, no. 7: 2056. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072056

APA StyleCampos-Alba, C. M., De la Higuera-Molina, E. J., Pérez-López, G., & Zafra-Gómez, J. L. (2019). Measuring the Efficiency of Public and Private Delivery Forms: An Application to the Waste Collection Service Using Order-M Data Panel Frontier Analysis. Sustainability, 11(7), 2056. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072056