Searching for the Next New Energy in Energy Transition: Comparing the Impacts of Economic Incentives on Local Acceptance of Fossil Fuels, Renewable, and Nuclear Energies

Abstract

1. Introduction

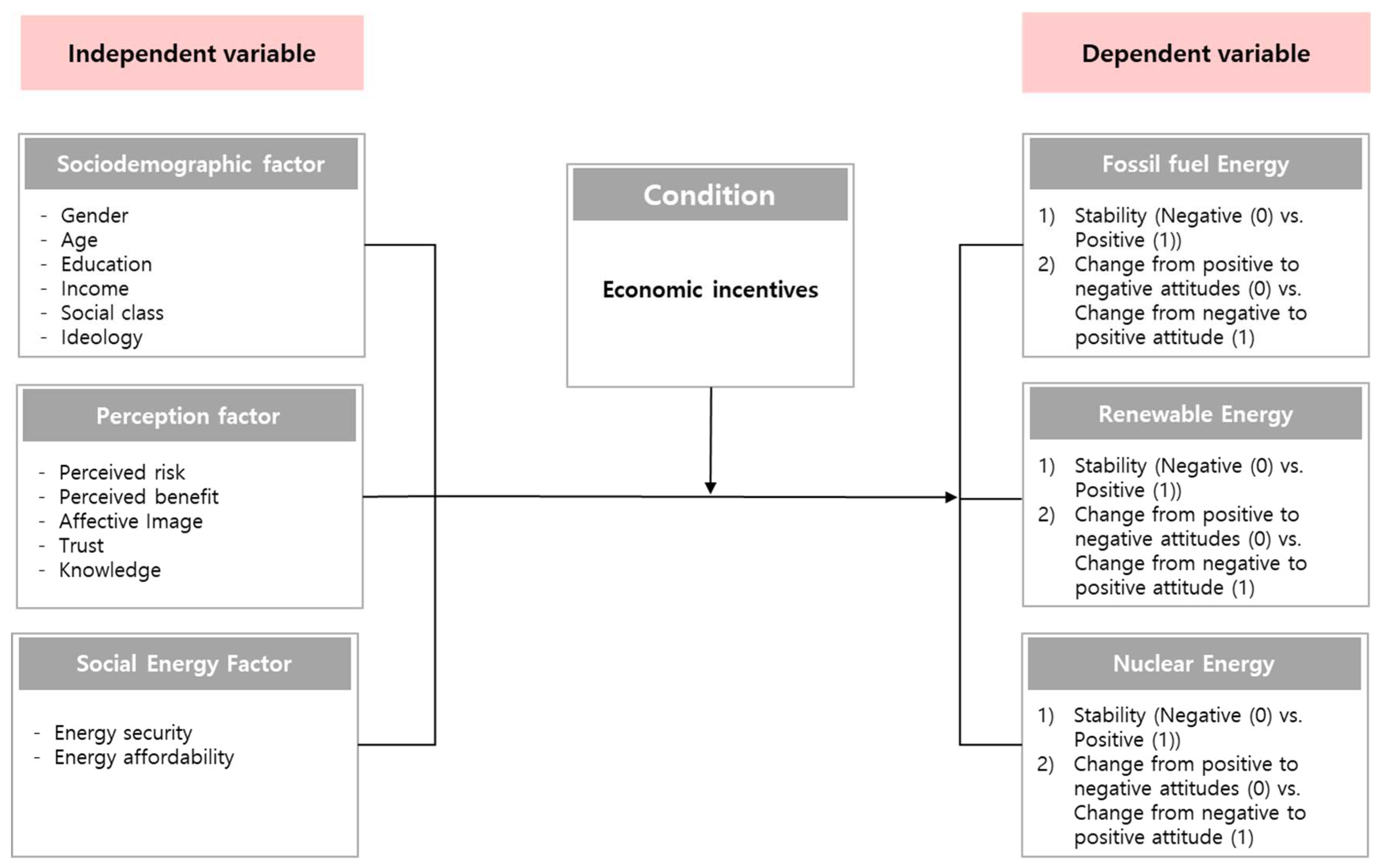

2. Theoretical Background and Research Model

2.1. Attitude Changes toward Different Types of Energy Sources

2.2. Economic Incentives

2.3. Perception Factors

2.4. Social Aspects of Energy

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Measure

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Testing for Structural Change

3.2.2. Binary Response Models

4. Results

4.1. Basic Data Analysis

4.2. Determinants of Acceptance Before and After Providing Economic Incentives

- Social status and knowledge have very similar pattern in all types of energies.

- Knowledge about energies and trust for government energy policy have a trade-off relationship.

- Economic incentives may not be distributed to all social classes equally.

4.3. Determinant of Attitude Changes: Degree of Attitude Change

4.4. Determinants of Attitude Change: Stability and Direction of Attitude Change

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion and Implications

- In the analysis of acceptance of various energies due to economic incentives, most of coefficients maintain the same sign and the magnitudes of the coefficients are not noticeably different throughout all types of energies. Only knowledge in renewable energy and perceived benefit in nuclear energy change the signs of coefficients from positive to negative. However, Chow tests reject the null hypothesis of no structural breaks and indicate that the economic incentives play some role to determine the acceptance of these energies.

- In the analysis of the degree of attitude change, each type of energy source depends on different sets of explanatory variables and is determined separately. No single explanatory variable affects the degree of attitude change throughout all these three energies. For example, age lowers the probability of the degree of attitude change in renewable and nuclear energies while energy affordability raises the probability of the degree of attitude change only in fossil fuels and renewable energies. On the other hand, education, log(income), location, social status, perceived risk, negative image, and energy security play no role in the degree of attitude change regardless of energy types.

- In the analysis of stability and the directional changes in attitude, each and every explanatory variable has consistent effect on each dependent variable, but no explanatory variable plays any role for all three energies. Only age, education, and ideology have no effect on any model of stability and the directional changes in attitudes.

- Education has no effect on any of these models.

- All the coefficients of log (income) are positive except Model 2 and Model 10 where the dependent variables are the acceptance of fossil fuels with economic incentives and stability, respectively.

- All the coefficients of location are positive except Model 9 where the dependent variable is change attitude on nuclear energy source.

- All the coefficients of social status are positive throughout all the models.

- Perceived benefit has mixed results. The coefficients are negative in Model 1, 6, 8, 9, and 15 but they are positive in Model 3, 5, 9’, and 11. In fossil fuels, perceived benefit has a negative effect on the acceptance of that energy source when economic incentives are not. In renewable energy source, benefit has a positive effect on acceptance when economic incentives are not provided but it has a negative effect on the attitude change. In nuclear energy source, perceived benefit has a positive effect on acceptance when economic incentives are not provided but it changes to negative when the economic incentives are provided. The coefficient is positive when the dependent variable is attitude change but it is negative when the dependent variable is directional changes of attitude.

- All the coefficients of perceived risk are negative throughout all the models.

- All the coefficients of negative image are negative throughout all the models.

- All the coefficients of trust are positive except Model 3 and Model 12 where the dependent variables are the acceptance of renewable energy without economic incentives and stability of renewable energy source, respectively.

- All the coefficients of knowledge are negative except Model 3 and 8’ which are for renewable energy source.

- All the coefficients of energy security are negative throughout all the models.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Representativeness of Sample

| Population | Sample | Percent gap (A-B) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent A (%) | Frequency | Percent B (%) | |

| Gender * | Female | 20,348,268 | 49.7 | 757 | 50.5 | −0.8 |

| Male | 20,572,715 | 50.3 | 743 | 49.5 | 0.8 | |

| Total | 40,920,983 | 100 | 150 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| Age * | 20–29 | 6,796,396 | 16.6 | 264 | 17.6 | −1.0 |

| 30–39 | 7,738,472 | 18.9 | 293 | 19.5 | −0.6 | |

| 40–49 | 8,726,984 | 21.3 | 292 | 21.9 | −0.6 | |

| 50–59 | 8,220,296 | 20.1 | 292 | 19.5 | 0.6 | |

| Over 60 | 9,438,835 | 23.1 | 322 | 21.5 | 1.6 | |

| Total | 40,920,983 | 100 | 1500 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| Education Level ** | Middle school | NA | 15.0 | 159 | 10.6 | 4.4 |

| Higher school | NA | 40.4 | 626 | 41.7 | −1.3 | |

| College | NA | 44.6 | 715 | 47.7 | −3.1 | |

| Total | NA | 100% | 1500 | 100 | 0 | |

References

- Hohenemser, C.; Renn, O. Chernobyl’s other legacy: Shifting public perceptions of nuclear risk. Environment 1988, 30, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B. Beliefs, Attitudes, and intentions toward nuclear energy before and after Chernobyl in a longitudinal within-subjects design. Environ. Behav. 1989, 21, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WIN—Gallup International. Gallup International Global Snap Poll on Tsunami in Japan and Impact on Views about Nuclear Energy, 2011. ICPSR Data Hold. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessides, I. The future of the nuclear industry reconsidered: Risks, uncertainties, and continued promise. Energy Policy 2012, 48, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsos, M.O. Nuclear Energy Update Poll. 2012. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/nuclear-energy-update-poll (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- Visschers, V.H.; Siegrist, M. How a nuclear power plant accident influences acceptance of nuclear power: Results of a longitudinal study before and after the Fukushima disaster. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Han, Y.; Hammitt, J.K.; Bi, J.; Liu, Y. Effect of the Fukushima nuclear accident on the risk perception of residents near a nuclear power plant in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19742–19747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prati, G.; Zani, B. The effect of the Fukushima nuclear accident on risk perception, antinuclear behavioral intentions, attitude, trust, environmental beliefs, and values. Environ. Behav. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. The Perception of Risk; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Visschers, V.; Siegrist, M. Differences in risk perception between hazards and between individuals. In Psychological Perspectives on Risk and Risk Analysis: Theory, Models, and Applications; Raue, M., Lermer, E., Streicher, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fischhoff, B.; Slovic, P.; Lichtenstein, S.; Read, S.; Combs, B. How safe is safe enough? A psychometric study of attitudes towards technological risks and benefits. Policy Sci. 1978, 9, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Morality and nuclear energy: Perceptions of risks and benefits, personal norms, and willingness to take action related to nuclear energy. Risk Anal. 2010, 30, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L.; Poortinga, W. Values, perceived risks and benefits, and acceptability of nuclear energy. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuya, T. Public response to the Tokai nuclear accident. Risk Anal. 2001, 21, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slovic, P. Trust, emotion, sex, politics, and science: Surveying the risk-assessment battlefield. Risk Anal. 1999, 19, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, L. Limits of knowledge and the limited importance of trust. Risk Anal. 2001, 21, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöberg, L. Risk Perception, emotion and policy: The case of nuclear technology. Eur. Rev. 2003, 11, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, R. NIMBY, CLAMP, and the location of new nuclear-related facilities: U.S. national and 11 Site-specific survey. Risk Anal. 2009, 29, 1242–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamura, E. Experience of technological and natural disaster and their impact on the perceived risk of nuclear accidents after the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan 2011: A Cross-country Analysis. J Socio Econ. 2012, 41, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demski, D.; Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N. Exploring public perceptions of energy security risks in the UK. Energy Policy 2014, 66, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, A.; Venables, D.; Spence, A.; Poortinga, W.; Demski, C.; Pidgeon, N. Nuclear power, climate change and energy security: Exploring British public attitudes. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 4823–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.; Demski, C.; Butler, C.; Parkhill, K.; Pidgeon, N. Public perceptions of demand-side management and a smarter energy future. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.; Slovic, P. The role of affect and worldviews as orienting dispositions in the perception and acceptance of nuclear power. J Appl. Psychol. 1996, 26, 1427–1453. [Google Scholar]

- Sütterlin, B.; Siegrist, M. Public acceptance of renewable energy technologies from an abstract versus concrete perspective and the positive imagery of solar power. Energy Policy 2017, 106, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigka, E.K.; Paravantis, J.A.; Mihalakakou, G.K. Social acceptance of renewable energy sources: A review of contingent valuation applications. Renew. Sustain. Rev. 2014, 32, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallett, A. Social acceptance of renewable energy innovations: The role of technology cooperation in urban Mexico. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2790–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Zolfagharzadeh, M.M.; SadAbadi, A.A.; Aslani, A.; Jafari, H. Social Acceptance of Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Challenges and Opportunities. Distrib. Gener. Altern. J. 2018, 33, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frewer, L.J.; Howard, C.; Shepherd, R. Understanding public attitudes to technology. J. Risk Res. 1998, 1, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y. Major psychological factors determining public acceptance of the siting of nuclear facilities. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 1147–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujikawa, N.; Tsuchida, S.; Shiotani, T. Changes in the factors influencing public acceptance of nuclear power generation in Japan since the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Risk Anal. 2016, 36, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vainio, A.; Paloniemi, R.; Weighing, V. The risks of nuclear energy and climate change: Trust in different information sources, perceived risks, and willingness to pay for alternatives to nuclear power. Risk Anal. 2017, 37, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B.L.; Brown, S.; Greenberg, M.; Kahn, M.A. Risk perception in context: The Savannah river site stakeholder study. Risk Anal. 1999, 19, 1019–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsos, M.O. Strong Global Opposition towards Nuclear Power. 2011. Available online: http://www.ipsos-mori.com (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Black, R. Nuclear Power Gets Little Public Support Worldwide. 2011. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-15864806 (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Kim, Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, W. Effect of the Fukushima nuclear disaster on global public acceptance of nuclear energy. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midden, C.J.; Verplanken, B. The stability of nuclear attitudes after chernobyl. J. Environ. Psychol. 1990, 10, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.B.; Kim, H.-K. Competition, economic benefits, trust, and risk perception in siting a potentially hazardous facility. Landsc. Plan. 2009, 91, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.H.; Keller, M.C.; Siegrist, M. Climate change benefits and energy benefit supply benefits as determinants of acceptance of nuclear power stations: Investigating an explanatory model. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 3621–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Sütterlin, B.; Keller, C. Why have some people changed their attitudes toward nuclear power after the accident in Fukushima? Energy Policy 2014, 69, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, D. The role of values in public beliefs and attitudes towards commercial wind energy. Energy Policy 2013, 58, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.H.; Cherry, T.L.; Kallbekken, S.; Torvanger, A. Willingness to accept local wind energy development: Does the compensation mechanism matter? Energy Policy 2016, 99, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesten, E.; Gjertsen, H. Economic Incentives for Marine Conservation; Conservation International: Arlington, VA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schall, D.L.; Mohnen, A. Incentives for energy-efficient behavior at the workplace: A natural field experiment on eco-driving in a company fleet. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 2626–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Takahara, S.; Nishikawa, M.; Homma, T. A case study of economic incentives and local citizens’ attitudes toward hosting a nuclear power plant in Japan: Impacts of the Fukushima accident. Energy Policy 2013, 59, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunreuther, H.; Easterling, D. The role of compensation in siting hazardous facilities. J. Anal. Manag. 1996, 15, 601–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S.; Oberholzer-Gee, F.; Eichenberger, R. The Old Lady Visits Your Backyard: A Tale of Morals and Markets. J. Political Econ. 1996, 104, 1297–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schively, C. Understanding the NIMBY and LULU Phenomena: Reassessing Our Knowledge Base and Informing Future Research. J. Plan. Lit. 2007, 21, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardnera, G.T.; Tiemannab, A.R.; Goulda, L.C.; Delucaa, D.R.; Dooba, L.W.; Stolwijka, J. Risk and benefit perceptions, acceptability judgments, and self-reported actions toward nuclear power. J. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 116, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.-C.; Kao, S.-F.; Wang, J.-D.; Su, C.-T.; Lee, C.-T.P.; Chen, R.-Y.; Chang, H.-L.; Ieong, M.C.F.; Chang, P.W. Risk perception, trust, and factors related to a planned new nuclear power plant in Taiwan after the 2011 Fukushima disaster. J. Radiol. Prot. 2013, 33, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, K.; Decker, T.; Roosen, J.; Menrad, K. Factors influencing citizens’ acceptance and non-acceptance of wind energy in Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kim, S. Comparative analysis of public attitudes toward nuclear power energy across 27 European countries by applying the multilevel model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehr, A.M.; Watts, G.R.; Hanratty, J.; Talmi, D. Emotional response to images of wind turbines: A psychophysiological study of their visual impact on the landscape. Landsc. Plan. 2015, 142, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.-J. Risk perception in Korea: A comparison with Japan and the United States. J. Risk Res. 2000, 3, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitefield, S.C.; Rosa, E.A.; Dan, A.; Dietz, T. The future of nuclear power: Value orientations and risk perception. Risk Anal. 2009, 29, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzenich, A.; Ziefle, M. Uncovering the Impact of Trust and Perceived Fairness on the Acceptance of Wind Power Plants and Electricity Pylons. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems, Funchal, Portugal, 16–18 March 2018; pp. 190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, H.-K.; Ellinger, A.E.; Hadjimarcou, J.; Traichal, P.A.; Bang, H. Consumer concern, knowledge, belief, and attitude toward renewable energy: An application of the reasoned action theory. Psychol. Mark. 2000, 17, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). What Is Energy Security? 2017. Available online: https://www.iea.org/topics/energysecurity/whatisenergysecurity (accessed on 2 December 2018).

- Teräväinen, T.; Lehtonen, M.; Martiskainen, M. Climate change, energy security, and risk—Debating nuclear new build in Finland, France and the UK. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 3434–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Efficiency Working Group. Energy Efficiency and Energy Affordability for Low-Income Households. Issue Paper 6; Energy Efficiency Working Group Issue Papers: 2008. 2008. Available online: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2009/ec/En4-100-6-2008E.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- Demski, D.; Evensen, D.; Pidgeon, N.; Spence, A. Public prioritisation of energy affordability in the UK. Energy Policy 2017, 110, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, G.C. Tests of Equality between Sets of Coefficients in Two Linear Regressions. Econometrica 1960, 28, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach; South-Western, Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, William. Pooling Data and Performing Chow Tests in Linear Regression. 2015. Available online: https://www.stata.com/support/faqs/statistics/pooling-data-and-chow-tests/#sect7 (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- He, G.; Mol, A.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Y. nuclear power in China after Fukushima: Understanding public knowledge, attitudes, and trust. J Risk Res. 2012, 17, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, J.B. Tests for Specification Errors in Classical Linear Least-Squares Regression Analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1969, 31, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J.A. Specification Tests in Econometrics. Econometrica 1978, 46, 1251–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Irresolvable cultural conflicts and conservation/development arguments: Analysis of Korea’s Saemangeum project. Policy Sci. 2003, 36, 125–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kim, S. Analysis of the impact of values and perception on climate change skepticism and its implication for public policy. Climate 2018, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Exploring the Effect of Four Factors on Affirmative Action Programs for Women. J. Women’s Stud. 2014, 20, 31–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Impact of the Fukushima nuclear accident on belief in rumors: The role of risk perception and communication. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, D. Does government make people happy? Exploring new research directions for government’s roles in happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 2012, 13, 875–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, S.; Wang, J. Individual perception vs. structural context: Searching for multilevel determinants of social acceptance of new science and technology across 34 countries. Sci. Public Policy 2014, 41, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Exploring the determinants of perceived risk of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korean Statistical Information System (KOSIS). Population. 2015. Available online: http://kosis.kr/index/index.do (accessed on 2 December 2018).

- OECD. Education at a Glance. 2015. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/ (accessed on 2 December 2018).

| Category | Variables | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptance | Acceptance without Economic Incentives provided (dependent variable) | Level of Acceptance for increasing the use of each energy type (fossil fuels, renewable, and nuclear energy). 5-point scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree |

| Acceptance with Economic Incentives provided (dependent variable) | Level of Acceptance for each energy-related facility (fossil fuels, renewable, and nuclear energy) to be built in your local area under sufficient economic compensation by government. 5-point scale: strongly disagree = 1, disagree = 2, neutral = 3, agree = 4, strongly agree = 5 | |

| Socio-demographic factors | Gender | Dummy variable (Male = 0, Female = 1) |

| Education | Dummy variable (high school graduate = 0, college graduate = 1) | |

| Income | Average monthly household income (measuring unit = 10,000 Korean Won) | |

| Location | Dummy variable (non-metropolitan area = 0, metropolitan area = 1) | |

| Social status | Self-declared social class. 10-point scale (lowest class = 1, …, highest class = 10) | |

| Ideology | Self-declared political stance. 10-point scale (conservative = 1, …, liberal = 10) | |

| Perception factors | Perceived benefit | Degree of benefit perceived from each type of energy (fossil fuels, renewable, and nuclear energy). 10-point scale. the least benefit = 1, …, the largest benefit = 10 |

| Perceived risk | Degree of risk perceived from each type of energy (fossil fuels, renewable, and nuclear energy). 10-point scale. the smallest risk = 1, …, the biggest risk = 10 | |

| Negative image | Instant image from each type of energy (fossil fuels, renewable, and nuclear energy). 10-point scale. Extremely positive image = 1, …, extremely negative image = 10 | |

| Knowledge | Degree of overall knowledge of each type (fossil fuels, renewable, and nuclear energy) of energy situation and policy. 5-point scale. No knowledge = 1, …, strong knowledge = 5 | |

| Trust | Credibility level on government’s energy policy. 5-point scale. Never trust = 1, …, strongly trust = 5 | |

| Social aspects of energy | Energy security | Personal acceptance of investing in oversea energy sources or taking higher tax burden for energy security. 5-point scale. Strongly disagree = 1, …, strongly agree = 5 |

| Energy affordability | Personal affordability level of energy expenses such as electricity bill. 5-point scale. Heavy burden = 1, …, no burden = 5 |

| Economic Incentive | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fossil Fuel Energy | Renewable Energy | Nuclear Energy | |||||||||||||||

| Oppose | Neutral | Accept | Total | Oppose | Neutral | Accept | Total | Oppose | Neutral | Accept | Total | ||||||

| No economic incentive | Fossil fuel energy | Oppose | N | 324 | 92 | 45 | 461 | Renewable energy | 19 | 12 | 29 | 60 | Nuclear energy | 481 | 85 | 19 | 585 |

| % | 70.3% | 20.0% | 9.8% | 100% (30.7%) | 31.7% | 20.0% | 48.3% | 100% (4.0%) | 82.2% | 14.5% | 3.2% | 100% (39.0%) | |||||

| Neutral | N | 185 | 231 | 84 | 500 | 19 | 52 | 50 | 121 | 228 | 243 | 79 | 550 | ||||

| % | 37.0% | 46.2% | 16.8% | 100% (33.3%) | 15.7% | 43.0% | 41.3% | 100% (8.1%) | 41.5% | 44.2% | 14.4% | 100% (36.7) | |||||

| Accept | N | 125 | 154 | 260 | 539 | 47 | 112 | 1160 | 1319 | 97 | 104 | 164 | 365 | ||||

| % | 23.2% | 28.6% | 48.2% | 100% (35.9%) | 3.6% | 8.5% | 87.9% | 100% (87.9%) | 26.6% | 28.5% | 44.9% | 100% (24.3) | |||||

| Total | N | 634 | 477 | 389 | 1500 | 85 | 176 | 1239 | 1500 | 806 | 432 | 262 | 1500 | ||||

| % | 42.3% | 31.8% | 25.9% | 100% | 5.7% | 11.7% | 82.6% | 100% | 53.7% | 28.8% | 17.5% | 100% | |||||

| Dependent Variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Acceptance of Fossil without Economic Incentives | Model 2: Acceptance of Fossil with Economic Incentives | |||||

| Coefficient (S.E.) | Beta Coefficient | Coefficient (S.E.) | Beta Coefficient | |||

| Independent variable | Socio-Demographic factors | Gender | 0.019 (0.043) | 0.010 | −0.060 (0.045) | −0.030 |

| Age | 0.001 (0.002) | 0.010 | 0.001 (0.002) | −0.007 | ||

| Education | −0.040 (0.054) | −0.021 | −0.024 (0.058) | −0.012 | ||

| Log(income) | −0.088 (0.054) | −0.039 | −0.162 *** (0.051) | −0.069 | ||

| Location | −0.023 (0.043) | −0.012 | 0.098 ** (0.045) | 0.048 | ||

| Social status | 0.085 *** (0.019) | 0.116 | 0.118 *** (0.019) | 0.154 | ||

| Ideology | −0.008 (0.015) | −0.013 | −0.016 (0.015) | −0.025 | ||

| Perception factors | Perceived benefit | −0.030 * (0.017) | −0.049 | −0.009 (0.018) | −0.014 | |

| Perceived risk | −0.096 *** (0.023) | −0.158 | −0.087 *** (0.025) | −0.137 | ||

| Negative image | −0.220 *** (0.023) | −0.345 | −0.239 *** (0.024) | −0.360 | ||

| Trust | 0.161 *** (0.035) | 0.123 | 0.173 *** (0.038) | 0.126 | ||

| Knowledge | −0.024 (0.039) | −0.017 | −0.109 *** (0.041) | −0.072 | ||

| Social aspects of energy | Energy security | −0.113 *** (0.033) | −0.086 | −0.070 ** (0.032) | −0.052 | |

| Energy affordability | −0.062 (0.039) | −0.042 | −0.125 *** (0.039) | −0.081 | ||

| Constant | 1.979 *** (0.458) | . | 2.240 *** (0.442) | |||

| Number of observations | 1500 | 1500 | ||||

| R square | 0.294 | 0.301 | ||||

| Adjusted R square | 0.287 | 0.295 | ||||

| Chow test | 6.57; p-value = 0 | |||||

| Dependent Variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 3: Acceptance of Renewable without Economic Incentives | Model 4: Acceptance of Renewable with Economic Incentives | |||||

| Coefficient (S.E.) | Beta Coefficient | Coefficient (S.E.) | Beta Coefficient | |||

| Independent variable | Socio-demographic factors | Gender | −0.050 (0.046) | −0.026 | −0.048 (0.050) | −0.023 |

| Age | 0.005 ** (0.002) | 0.073 | 0.005 ** (0.002) | 0.066 | ||

| Education | 0.009 (0.058) | 0.005 | −0.016 (0.066) | −0.008 | ||

| Log (income) | 0.142 ** (0.058) | 0.064 | 0.172 *** (0.066) | 0.072 | ||

| Location | 0.033 (0.031) | 0.017 | 0.033 (0.051) | 0.016 | ||

| Social status | −0.029 (0.021) | −0.039 | 0.037 * (0.022) | 0.047 | ||

| Ideology | 0.060 *** (0.015) | 0.098 | 0.020 (0.017) | 0.030 | ||

| Perception factors | Perceived benefit | 0.030 ** (0.012) | 0.066 | 0.004 (0.014) | 0.008 | |

| Perceived risk | −0.048 ** (0.022) | −0.090 | −0.040 * (0.023) | −0.070 | ||

| Negative image | −0.184 *** (0.028) | −0.300 | −0.192 *** (0.030) | −0.293 | ||

| Trust | −0.161 *** (0.037) | −0.123 | −0.050 (0.043) | −0.036 | ||

| Knowledge | 0.096 ** (0.039) | 0.067 | −0.090 ** (0.043) | −0.059 | ||

| Social aspects of energy | Energy security | 0.004 (0.033) | 0.003 | 0.031 (0.038) | 0.022 | |

| Energy affordability | −0.044 (0.038) | −0.030 | −0.096 ** (0.043) | −0.061 | ||

| Constant | −0.310 (0.450) | −0.338 (0.506) | ||||

| Number of observations | 1500 | 1500 | ||||

| R square | 0.198 | 0.143 | ||||

| Adjusted R square | 0.190 | 0.134 | ||||

| Chow test | 3.77; p-value = 0.00 | |||||

| Dependent Variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 5: Acceptance of Nuclear without Economic Incentives | Model 6: Acceptance of Nuclear with Economic Incentives | |||||

| Coefficient (S.E.) | Beta Coefficient | Coefficient (S.E.) | Beta Coefficient | |||

| Independent variable | Socio-demographic factors | Gender | 0.011 (0.042) | 0.006 | −0.041 (0.042) | −0.020 |

| Age | 0.0002 (0.002) | 0.002 | −0.0001 (0.002) | −0.001 | ||

| Education | 0.079 (0.052) | 0.040 | 0.004 (0.053) | 0.002 | ||

| Log(income) | −0.043 (0.051) | −0.019 | −0.052 (0.053) | −0.023 | ||

| Location | 0.154 *** (0.043) | 0.078 | 0.064 (0.042) | 0.032 | ||

| Social status | 0.026 (0.018) | 0.035 | 0.048 *** (0.017) | 0.064 | ||

| Ideology | −0.001 (0.015) | −0.001 | 0.002 (0.014) | 0.003 | ||

| Perception factors | Perceived benefit | 0.049 *** (0.011) | 0.108 | −0.025 ** (0.011) | −0.055 | |

| Perceived risk | −0.039 ** (0.016) | −0.087 | −0.079 *** (0.016) | −0.173 | ||

| Negative image | −0.195 *** (0.016) | −0.426 | −0.204 *** (0.017) | −0.440 | ||

| Trust | 0.099 *** (0.036) | 0.075 | 0.101 *** (0.035) | 0.075 | ||

| Knowledge | −0.052 (0.039) | −0.035 | −0.062 * (0.037) | −0.042 | ||

| Social aspects of energy | Energy security | −0.001 (0.031) | −0.001 | −0.056 * (0.031) | −0.041 | |

| Energy affordability | 0.004 (0.039) | 0.003 | −0.029 (0.033) | −0.019 | ||

| Constant | 1.145 *** (0.422) | 1.860 *** (0.431) | ||||

| Number of Observations | 1500 | 1500 | ||||

| R Square | 0.328 | 0.360 | ||||

| Adjusted R Square | 0.322 | 0.354 | ||||

| Chow Test | 9.89; p-value = 0.00 | |||||

| Dependent Variable | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 7: Attitude Change on Fossil Fuels | Model 8: Attitude Change on Renewable Energy | Model 9: Attitude Change on Nuclear Energy | ||||||

| Coefficient (S.E.) | Beta Coefficient | Coefficient (S.E.) | Beta Coefficient | Coefficient (S.E.) | Beta Coefficient | |||

| Independent variable | Socio-demographic factors | Gender | −0.057 (0.036) | −0.042 | 0.001 (0.036) | 0.001 | −0.053 (0.050) | −0.028 |

| Age | −0.001 (0.002) | −0.018 | −0.0001 (0.002) | −0.001 | −0.0002 (0.002) | −0.003 | ||

| Education | 0.011 (0.046) | 0.008 | −0.017 (0.046) | −0.012 | −0.077 (0.063) | −0.040 | ||

| Log(income) | −0.053 (0.046) | −0.033 | 0.020 (0.044) | 0.013 | −0.010 (0.062) | −0.004 | ||

| Location | 0.087 ** (0.037) | 0.063 | −0.0002 (0.036) | 0.000 | −0.093 * (0.051) | −0.048 | ||

| Social status | 0.024 * (0.014) | 0.045 | 0.045 *** (0.017) | 0.084 | 0.022 (0.021) | 0.031 | ||

| Ideology | −0.006 (0.013) | −0.013 | −0.027 ** (0.012) | −0.062 | 0.003 (0.017) | 0.004 | ||

| Perception factors | Perceived benefit | 0.015 (0.014) | 0.034 | −0.018 * (0.009) | −0.054 | −0.076 *** (0.013) | −0.171 | |

| Perceived risk | 0.007 (0.020) | 0.015 | 0.006 (0.013) | 0.014 | −0.041 ** (0.020) | −0.093 | ||

| Negative image | −0.014 (0.018) | −0.031 | −0.006 (0.016) | −0.013 | −0.009 (0.020) | −0.020 | ||

| Trust | 0.008 (0.031) | 0.009 | 0.076 ** (0.030) | 0.080 | 0.002 (0.043) | 0.001 | ||

| Knowledge | −0.061 * (0.035) | −0.059 | −0.127 *** (0.031) | −0.121 | −0.011 (0.047) | −0.007 | ||

| Social aspects of energy | Energy security | 0.031 (0.026) | 0.033 | 0.018 (0.027) | 0.019 | −0.056 (0.037) | −0.043 | |

| Energy affordability | −0.046 (0.029) | 0.043 | −0.036 (0.030) | 0.033 | −0.034 (0.044) | −0.023 | ||

| Constant | 0.188 (0.374) | −0.019 (0.337) | 0.735 (0.530) | |||||

| F-Value | 1.39 | 2.19 *** | 3.99 *** | |||||

| R Square | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.035 | |||||

| Adjusted R Square | 0.004 | 0.014 | 0.026 | |||||

| Dependent Variable | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 7’: Attitude Change on Fossil Fuels | Model 8’: Attitude Change on Renewable Energy | Model 9’: Attitude Change on Nuclear Energy | ||||||

| Coefficient (Robust S.E.) | Beta | Coefficient (Robust S.E.) | Beta | Coefficient (Robust S.E.) | Beta | |||

| Independent variable | Socio-demographic factors | Gender | 0.031 (0.025) | 0.032 | −0.002 (0.026) | −0.002 | 0.014 (0.026) | 0.014 |

| Age | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.027 | −0.003 **(0.001) | −0.077 | −0.002 * (0.001) | −0.056 | ||

| Education | 0.019 (0.032) | 0.020 | −0.052 (0.032) | −0.052 | −0.009 (0.033) | −0.009 | ||

| Log(income) | −0.031 (0.031) | −0.028 | −0.041 (0.033) | −0.036 | −0.045 (0.032) | −0.039 | ||

| Location | 0.015 (0.026) | 0.063 | 0.010 (0.026) | 0.011 | 0.037 (0.026) | 0.036 | ||

| Social status | −0.002 (0.011) | −0.006 | −0.010 (0.011) | −0.027 | −0.008 (0.011) | −0.021 | ||

| Ideology | −0.016 * (0.009) | −0.013 | −0.002 (0.009) | −0.007 | 0.005 (0.009) | 0.016 | ||

| Perception factors | Perceived benefit | 0.014 (0.009) | 0.045 | 0.009 (0.007) | 0.038 | 0.031 ***(0.006) | 0.132 | |

| Perceived risk | 0.022 (0.012) | 0.037 | 0.002 (0.010) | 0.005 | 0.002 (0.009) | 0.009 | ||

| Negative image | 0.022 * (0.012) | 0.069 | 0.019 (0.012) | 0.060 | 0.002 (0.009) | 0.007 | ||

| Trust | 0.039 * (0.020) | 0.060 | 0.007 (0.021) | 0.011 | 0.007 (0.021) | 0.011 | ||

| Knowledge | 0.008 (0.022) | 0.011 | 0.050 **(0.023) | 0.067 | −0.027 (0.023) | −0.036 | ||

| Social aspects of energy | Energy security | 0.025 (0.018) | 0.039 | −0.007 (0.019) | −0.010 | 0.020 (0.019) | 0.029 | |

| Energy affordability | 0.041 **(0.020) | 0.056 | 0.058 ***(0.021) | 0.076 | 0.032 (0.021) | 0.041 | ||

| Constant | 0.372 (0.262) | 0.587 **(0.259) | 0.602 **(0.263) | |||||

| F-Value | 2.22 *** | 1.92 ** | 3.24 *** | |||||

| R square | 0.020 | 0.023 | 0.027 | |||||

| Dependent Variable | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 10: Stability, Negative (=0) vs. Positive (=1) Response | Model 11: Change from Positive to Negative Response (=0) vs. from Negative to Positive Response (=1) | |||||||

| LPM | Probit | Logit | LPM | Probit | Logit | |||

| Independent variable | Socio-demographic factors | Gender | −0.035 (0.031) | −0.089 (0.136) | −0.118 (0.239) | −0.026 (0.036) | −0.037 (0.102) | −0.124 (0.169) |

| Age | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.002 (0.006) | 0.004 (0.011) | −0.002 (0.002) | −0.005 (0.005) | −0.007 (0.008) | ||

| Education | −0.027 (0.040) | −0.131 (0.175) | −0.177 (0.313) | 0.28 (0.045) | 0.082 (0.127) | 0.132 (0.210) | ||

| Log(income) | −0.091 ** (0.037) | −0.240 * (0.177) | −0.497 * (0.292) | −0.064 (0.043) | −0.184 (0.122) | −0.300 (0.202) | ||

| Location | 0.138 ** (0.032) * | 0.464 *** (0.139) | 0.837 *** (0.248) | 0.115 *** (0.038) | 0.325 *** (0.105) | 0.534 *** (0.175) | ||

| Social status | 0.054 *** (0.013) | 0.244 *** (0.062) | 0.460 *** (0.107) | 0.008 (0.016) | 0.025 (0.044) | 0.038 (0.073) | ||

| Ideology | −0.003 (0.010) | −0.003 (0.047) | −0.0249 (0.084) | −0.004 (0.012) | −0.014 (0.034) | −0.020 (0.057) | ||

| Perception factors | Perceived benefit | 0.008 (0.009) | −0.027 (0.053) | −0.044 (0.097) | 0.026 * (0.015) | 0.074 * (0.042) | 0.123 * (0.070) | |

| Perceived risk | −0.016 (0.016) | −0.119 * (0.065) | −0.212 * (0.118) | 0.010 (0.017) | 0.028 (0.048) | 0.047 (0.081) | ||

| Negative image | −0.125 *** (0.017) | −0.532 *** (0.071) | −0.939 *** (0.129) | −0.003 (0.018) | −0.010 (0.052) | −0.015 (0.086) | ||

| Trust | 0.062 *** (0.024) | 0.312 *** (0.110) | 0.561 *** (0.207) | −0.020 (0.032) | −0.059 (0.088) | −0.094 (0.146) | ||

| Knowledge | −0.033 (0.027) | −0.240 * (0.130) | −0.353 (0.225) | 0.013 (0.032) | 0.037 (0.091) | 0.060 (0.149) | ||

| Social aspects of energy | Energy security | −0.076 *** (0.023) | −0.292 *** (0.100) | −0.491 *** (0.174) | 0.014 (0.026) | 0.036 (0.074) | 0.066 (0.123) | |

| Energy affordability | −0.084 *** (0.024) | −0.389 *** (0.112) | −0.644 *** (0.199) | 0.022 (0.030) | 0.068 (0.084) | 0.105 (0.136) | ||

| Constant | 1.629 *** (0.294) | 4659 *** (1.399) | 8.090 *** (2.470) | 0.443 (0.379) | −0.103 (1.081) | −0.209 (1.780) | ||

| Log likelihood | −223.868 | −222.942 | −421.957 | −422.038 | ||||

| N | 584 | 584 | 584 | 685 | 685 | 685 | ||

| R2 | 0.467 | 0.442 | 0.444 | 0.025 | 0.020 | 0.020 | ||

| RESET | 12.04 *** | 0.68 | ||||||

| Hausman Test | 37.46 *** | 4.00 | ||||||

| Dependent Variable | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 14: Stability, Negative (=0) vs. Positive (=1) Response | Model 15: Change from Positive to Negative Response (=0) vs. from Negative to Positive Response (=1) | |||||||

| LPM | Probit | Logit | LPM | Probit | Logit | |||

| Independent variable | Socio-demographic factors | Gender | −0.006 (0.008) | −0.132 (0.213) | −0.343 (0.559) | −0.077 (0.059) | −0.191 (0.162) | −0.321 (0.269) |

| Age | 0.0004 (0.0004) | 0.018 (0.011) | 0.034 (0.028) | −0.001 (0.003) | −0.007 (0.008) | −0.012 (0.013) | ||

| Education | 0.001 (0.010) | 0.156 (0.308) | 0.193 (0.772) | −0.021 (0.072) | −0.123 (0.205) | −0.216 (0.337) | ||

| Log(income) | 0.019 ** (0.010) | 0.547 ** (0.237) | 1.106 * (0.568) | −0.021 (0.076) | −0.088 (0.212) | −0.170 (0.359) | ||

| Location | 0.005 (0.008) | 0.081 (0.229) | 0.043 (0.590) | −0.114 * (0.059) | −0.262 (0.171) | −0.436 (0.282) | ||

| Social status | 0.007 ** (0.003) | 0.200 ** (0.087) | 0.431 ** (0.215) | 0.011 (0.025) | 0.066 (0.069) | 0.113 (0.115) | ||

| Ideology | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.099 (0.072) | 0.219 (0.189) | −0.030 (0.020) | −0.093 (0.058) | −0.147 (0.093) | ||

| Perception factors | Perceived benefit | 0.0004 (0.001) | 0.049 (0.049) | 0.074 (0.128) | −0.001 (0.017) | 0.050 (0.080) | 0.081 (0.100) | |

| Perceived risk | −0.006 * (0.003) | −0.141 ** (0.057) | −0.295 * (0.131) | 0.017 (0.024) | 0.053 (0.077) | 0.098 (0.127) | ||

| Negative image | −0.009 ** (0.004) | −0.165 ** (0.064) | −0.330 ** (0.150) | 0.034 (0.027) | −0.068 (0.062) | −0.120 (0.131) | ||

| Trust | −0.007 (0.005) | −0.349 ** (0.159) | −0.825 ** (0.401) | 0.036 (0.048) | 0.097 (0.139) | 0.157 (0.234) | ||

| Knowledge | −0.007 (0.005) | −0.179 (0.169) | −0.471 (0.435) | −0.100 (0.063) | −0.271 (0.170) | −0.446 (0.281) | ||

| Social aspects of energy | Energy security | 0.001 (0.006) | −0.045 (0.172) | 0.137 (0.423) | −0.063 (0.046) | −0.187 (0.125) | −0.314 (0.206) | |

| Energy affordability | 0.000 (0.007) | −0.058 (0.190) | −0.177 (0.465) | −0.019 (0.050) | −0.002 (0.139) | −0.010 (0.233) | ||

| Constant | 0.872 *** (0.064) | −0.685 (1.874) | −0.424 (4.486) | 0.965 (0.628) | 1.657 (1.821) | 2.883 (3.078) | ||

| Log likelihood | −73.218 | −75.287 | −165.084 | −165.038 | ||||

| N | 1,179 | 1,179 | 1,179 | 269 | 269 | 269 | ||

| R2 | 0.044 | 0.247 | 0.226 | 0.067 | 0.041 | 0.041 | ||

| RESET | 7.99 *** | 0.89 | ||||||

| Hausman Test | 12.55 | 4.14 | ||||||

| Dependent Variable | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 14: Stability, Negative (=0) vs. Positive (=1) Response | Model 15: Change from Positive to Negative Response (=0) vs. from Negative to Positive Response (=1) | |||||||

| LPM | Probit | Logit | LPM | Probit | Logit | |||

| Independent variable | Socio-demographic factors | Gender | −0.033 (0.024) | −0.295 * (0.168) | −0.555 * (0.311) | −0.038 (0.037) | −0.111 (0.110) | −0.188 (0.186) |

| Age | −0.0004 (0.001) | −0.004 (0.007) | −0.011 (0.014) | −0.002 (0.002) | −0.005 (0.005) | −0.009 (0.009) | ||

| Education | 0.052 * (0.029) | 0.332 (0.205) | 0.541 (0.389) | −0.058 (0.048) | −0.171 (0.141) | −0.289 (0.233) | ||

| Log(income) | −0.022 (0.032) | −0.104 (0.198) | −0.159 (0.377) | −0.036 (0.046) | −0.095 (0.134) | −0.175 (0.226) | ||

| Location | 0.0240 (0.025) | 0.157 (0.162) | 0.291 (0.305) | −0.054 (0.039) | −0.162 (0.118) | −0.274 (0.199) | ||

| Social status | −0.002 (0.010) | 0.041 (0.065) | 0.044 (0.123) | 0.020 (0.016) | −0.062 (0.046) | 0.102 (0.076) | ||

| Ideology | 0.007 (0.008) | 0.002 (0.056) | −0.004 (0.108) | 0.003 (0.013) | −0.011 (0.038) | 0.018 (0.065) | ||

| Perception factors | Perceived benefit | −0.001 (0.005) | 0.020 (0.048) | 0.043 (0.091) | −0.040 *** (0.010) | −0.122 *** (0.030) | −0.203 *** (0.051) | |

| Perceived risk | −0.021 ** (0.011) | −0.055 (0.051) | −0.084 (0.092) | −0.023 ** (0.011) | −0.070 ** (0.034) | −0.116 ** (0.056) | ||

| Negative image | −0.107 *** (0.011) | −0.593 *** (0.064) | −1.071 *** (0.122) | −0.019 (0.012) | −0.054 (0.037) | −0.095 (0.062) | ||

| Trust | 0.069 *** (0.019) | 0.715 *** (0.141) | 1.319 *** (0.266) | 0.006 (0.029) | 0.017 (0.090) | 0.035 (0.149) | ||

| Knowledge | −0.038 * (0.019) | −0.389 *** (0.128) | −0.679 *** (0.240) | −0.008 (0.033) | −0.022 (0.100) | −0.044 (0.167) | ||

| Social aspects of energy | Energy security | −0.019 (0.016) | −0.170 (0.121) | 0.305 (0.224) | −0.016 (0.028) | −0.053 (0.084) | −0.094 (0.139) | |

| Energy affordability | −0.040 ** (0.019) | −0.169 (0.126) | −0.306 (0.225) | 0.034 (0.031) | 0.097 (0.092) | 0.164 (0.151) | ||

| Constant | 1.266 *** (0.253) | 3.255 (1.798)* | 5.842 * (3.386) | 0.973 *** (0.363) | 1.407 (1.088 | 2.510 (1.807) | ||

| Log likelihood | −155.697 | −156.951 | −358.132 | −358.054 | ||||

| N | 645 | 645 | 645 | 612 | 612 | 612 | ||

| R2 | 0.533 | 0.5742 | 0.571 | 0.048 | 0.041 | 0.041 | ||

| RESET | 104.42 *** | 0.66 | ||||||

| Hausman Test | 35.64 *** | 7.01 | ||||||

| Fossil Fuel | Renewable | Nuclear | Fossil Fuel | Renewable | Nuclear | Fossil Fuel | Renewable | Nuclear | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7/7’ | 8/8’ | 9/9’ | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| Socio-demographic factors | Gender | − | ||||||||||||||

| Age | + | + | /− | /− | ||||||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||||||

| Log(income) | − | + | + | − | + | |||||||||||

| Location | + | + | +/ | −/ | + | + | ||||||||||

| Social status | + | + | + | + | +/ | +/ | + | + | ||||||||

| Ideology | + | /− | −/ | |||||||||||||

| Perception factors | Perceived benefit | − | + | + | − | −/− | −/+ | + | − | |||||||

| Perceived risk | − | − | − | − | − | − | −/ | − | − | − | ||||||

| Negative image | − | − | − | − | − | − | /− | − | − | − | ||||||

| Trust | + | + | − | + | + | /+ | +/ | + | − | + | ||||||

| Knowledge | − | + | − | − | −/ | −/+ | − | |||||||||

| Social aspects of energy | Energy security | − | − | − | − | |||||||||||

| Energy affordability | − | − | /+ | /+ | − | |||||||||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, D. Searching for the Next New Energy in Energy Transition: Comparing the Impacts of Economic Incentives on Local Acceptance of Fossil Fuels, Renewable, and Nuclear Energies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2037. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072037

Kim S, Lee JE, Kim D. Searching for the Next New Energy in Energy Transition: Comparing the Impacts of Economic Incentives on Local Acceptance of Fossil Fuels, Renewable, and Nuclear Energies. Sustainability. 2019; 11(7):2037. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072037

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Seoyong, Jae Eun Lee, and Donggeun Kim. 2019. "Searching for the Next New Energy in Energy Transition: Comparing the Impacts of Economic Incentives on Local Acceptance of Fossil Fuels, Renewable, and Nuclear Energies" Sustainability 11, no. 7: 2037. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072037

APA StyleKim, S., Lee, J. E., & Kim, D. (2019). Searching for the Next New Energy in Energy Transition: Comparing the Impacts of Economic Incentives on Local Acceptance of Fossil Fuels, Renewable, and Nuclear Energies. Sustainability, 11(7), 2037. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072037