On the Inevitable Bounding of Pluralism in ESE—An Empirical Study of the Swedish Green Flag Initiative

Abstract

1. Introduction

“On the one hand there is a deep concern about the state of the planet and a sense of urgency that demands a break with existing non-sustainable systems, lifestyles, and routines, while on the other there is a conviction that it is wrong to persuade, influence, or even educate people towards pre- and expert-determined ways of thinking and acting.”[6] (p. 150)

“Transformative learning is based on the notion of recreating underlying thoughts and assumptions about the systems, structures, and societies that we are a part of. This includes an ethical dimension related to the intentions, methods, and preconceived outcomes suggested by the educator. What are we transforming students into? Are we biased toward certain outcomes for the transformation?”[8] (p. 86)

2. Materials and Methods

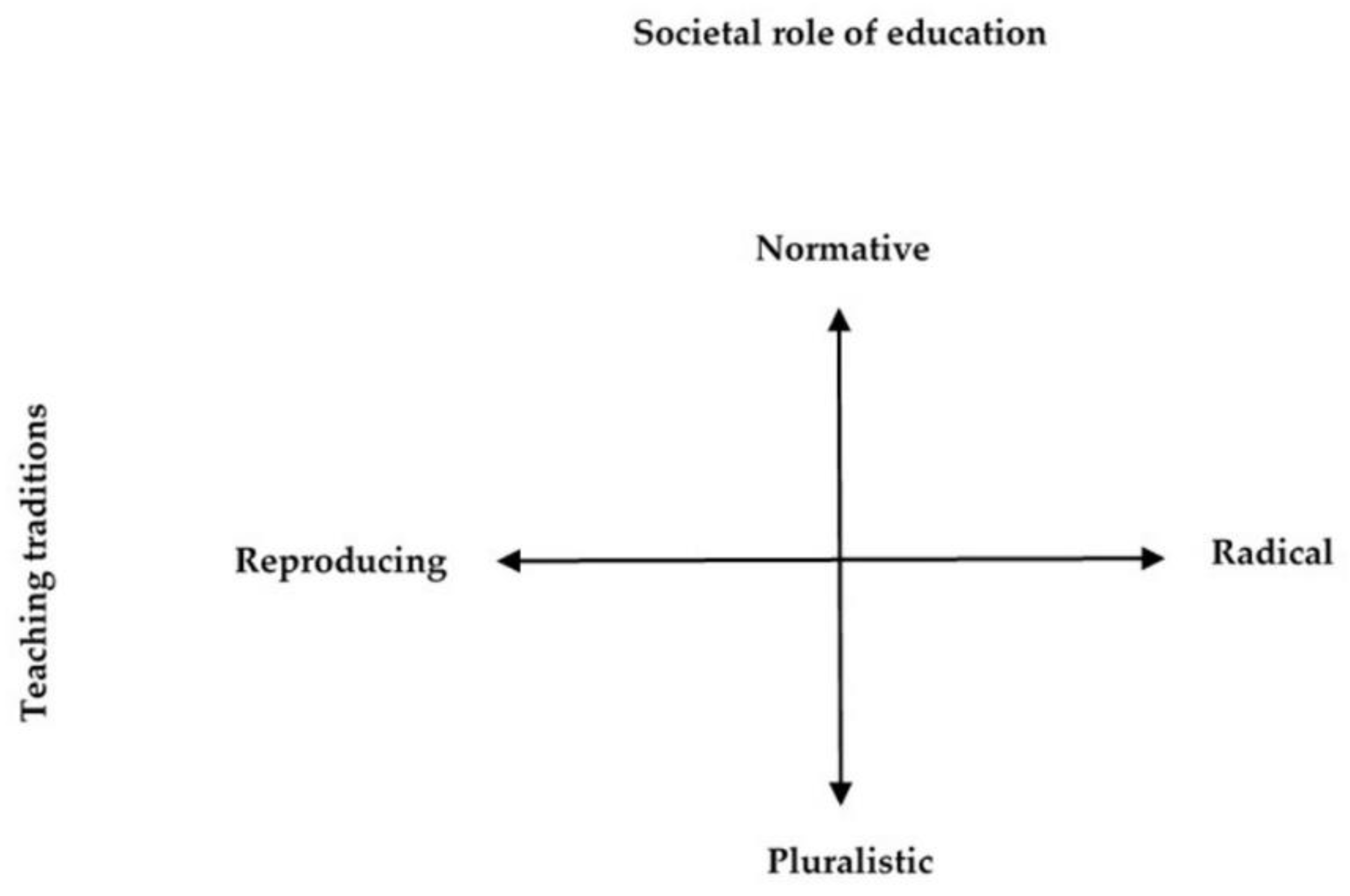

- “Normative”, in which ESE is about promotion of objectives, morals and values that are defined before the implementation;

- “Pluralistic”, in which ESE is about enabling democratic discussion based on different perspectives, including opposing fact claims and norms, with the aim of arriving at moral judgements during the implementation.

- “Reproducing”, i.e. fostering citizens that accept their role in society and comply with prevailing values, norms and institutions. This definition corresponds to what Jickling and Wals call an “authoritative” view of the societal role of educated persons [23], as well as to what e.g., Biesta has conceptualized as the “socializing” function of education [53].

“[One] question concerns to what extent the purpose of education should be seen as conserving or change-inducing at societal level. No matter how the question is answered, each reply illustrates that teaching has political and moral consequences that are dependent on the teacher’s conscious or subconscious didactic choices.”[55] (p. 42; translated by us)

- desirable or actual influence from Green Flag activities on a societal level, and

- correspondence between Green Flag activities and the normative and pluralistic teaching traditions.

- At the onset of each interview, the respondents were asked to describe their views on (a) desirable or actual influence from Green Flag activities on a societal level; and (b) correspondence between Green Flag activities and the normative and pluralistic teaching traditions. These two points mirror the analytical questions applied to the written material.

- Then, the respondents were pointed to possible tensions elicited from the written material and the initial stage of the interviews, as interpreted by us. The respondents were asked if they agreed on these possible tensions and, if so, how they are handled, or could be handled, in the Green Flag initiative.

3. Results

3.1. Frames Elicited from Written Green Flag Material

“It is important to lecture about grave future issues, and pedagogues should not be afraid to make students concerned. Instead, it is about helping young people to handle their worries in a constructive way. […] In order to sense hope, it is important to feel that it is possible to act and exercise influence, as well as trust in other actors to do something.”(p. 3)

“As students grow older it becomes important also to visualize interconnections, and to discuss solutions at a higher level of abstraction than lifestyle and everyday choices. One example is to discuss what happens if we as individuals or groups decrease our consumption of fossil fuels. This might inspire other individuals and groups around the world to do the same. It might also lead to decreasing fossil fuel prices, which might cause others to increase their consumption. Therefore, agreements at higher levels need to be discussed as well, e.g., carbon dioxide fees or cap and share. If not, there is a risk that many students remain at the level of the private sphere in their reasoning about the climate issue.”(p. 5)

”Education aiming for agency should have democracy built in to its objectives, means and methods. The education should convey knowledge about basic democratic values, but it should also, in accordance with the Swedish national Curriculum […], be implemented through democratic modes of work […]”(p. 4)

“Environmental issues are increasingly viewed as conflicts of interests among humans, including ecological as well as social and economic sustainability aspects, which makes them more political. The task of the school from a pluralistic perspective is to critically examine and analyze both facts and values without providing readymade answers regarding what is a correct choice.”(p. 5)

“The curriculum states that the school should be open to divergent opinions and encourage that these are articulated. At the same time, it is important not to lose other parts of the value foundation [of the curriculum], such as respect for human rights and that all humans are equal in dignity.”(p. 5)

“This escalator shows how waste is managed. It is best if we keep ourselves at the top part of the escalator. Questions to consider: 1. The top step [of the escalator] is about decreasing the amount of waste from the start. How is this done? […] 5. Why is it important to reuse and recycle when possible?”[58] (p. 3)

“You are citizens of Tuvalu, an island nation in the Pacific Ocean. Your beautiful nation is threatened by climate change. The sea level is rising and threatens to flood the islands, salt water destroys the soil, and the coral reefs outside the coast are affected when the sea becomes warmer and more acid. Within a couple of decades, it might be that you have to abandon your islands.” […] “The students are given the task to write a letter to the leaders of the world to explain what is going on in Tuvalu, the reasons behind this, and what needs to be done to avoid that the islands are flooded.”[59] (p. 12)

3.2. Frames Elicited from Interviews with Green Flag Strategists

“So, if we return to your question why we are doing this? Well, we do it because we want to reach out with sustainability issues to children and youth, to achieve a molding effect, to influence the future. […] So, this is the reason. When it comes to littering, we have worked more or less with it [over time]. We supply pedagogical material about the littering issue. That is our role.”

“The methodology has partly relied on four corner exercises, the hot chair, that sort of things… [One example is] refrigerators in China. In the early 90’s, this seemed like an odd inquiry, but since then there has been a lot of discussion about the enormous increase in material standards in China. ‘We don’t have a right to decide about refrigerators in China’—that would be one corner [when doing the exercise]. ‘We should export environmentally friendly refrigerators to China’ would be another corner. ‘We should send our old refrigerators to China for reuse’ would be another corner. ‘We should abolish refrigerators in China’ would be another corner. People would stand in different corners, as a basis for discussion. You could say that this is the holistic view of environmental education that has been dominating lately and is expressed through the curriculum in my view—that we should provide students with a capacity to understand sustainable development and then make decisions themselves.”

“My impression is that schools and teachers believe that they are more pluralistic than they are. We see this when we ask about the extent of student involvement—they describe this in very different ways… […] Sometimes we feel that we nag and nag just by raising the question [of student involvement]... But how it is implemented is a different matter… Some [teachers] do a lot, they try to collect information about how students think. There is an awareness that this is something good, that it strengthens the education. But on the other hand, in some sense they [the teachers] are forced to think along those lines. Each teacher solves the issue in their own way. […] It is a process I think, speaking of development, to abandon a view that students are empty sheets who you are supposed to teach values that you believe in. There is a great span in the pluralistic thinking; in which perspectives you include. We have not reached as far as you would think. There is plenty of valuing in schools, regarding how students express themselves. […] The question is to what extent this can be taken out. Perhaps it is better to refer to the curriculum [as a basis for valuing how students express themselves]. Maybe that is more realistic. Then it is at least clear where the valuing comes from, so that you can relate to it.”

“When it comes to sustainability issues—then things come to a head, there are certain things that are not feasible. I believe that this is very difficult for teachers… […] you notice that they have an idea about what a good society looks like, and what sound values are. You cannot desire more cars. It is probably difficult for teachers to allow conversations among students that ends with a conclusion that grown-ups have not approved of as sustainable. […] We want to work with this, but at the same time, you cannot pretend that students can have a say on everything that we work with, that is not feasible. Instead, you have to follow a curriculum where there are certain objectives that teachers should strive for. So instead, we have called on teachers to examine what students see and think and wonder about and are interested in; we have tried to stress how important it is to pose open questions and take the preunderstanding of students as a starting point; and other things that I believe enable pluralistic approaches. […] In our trainings [for teachers], we have tried to help by talking about sustainability issues as complex questions without right or wrong answers. The teachers are like ‘can you please tell us what is correct?’. Then I can only tell them that there are pros and cons with everything, and that you need to support the students in acknowledging that it is a complex world and in using information at hand to reach decisions. But the teachers might not be there themselves, they ask ‘how should one do, how should one think?’. I believe that our approach contributes to pluralistic thinking; there are no truths […] and that teachers do not have to know, because it is possible to explore together with students. One day, evidence says that it is better to buy an organic apple, but the next day…”

”The value foundation [of the curriculum] serves a purpose; that students should gain certain insights and understand certain things and become good citizens and so on, and that is decided by the government and the parliament. […] In Canada, at least in some states, fact-based knowledge is the realm of the school, while norms, values and attitudes are the task of the church and the hockey club. […] It is a completely different view of education. It is an interesting question—to what extent should the state govern [education]?”

“I believe that this is a fairly common misconception; people say that it [Green Flag] is only about recycling. If you think so, you have not looked carefully into the tool. Of course, many [schools] work with recycling. The ecological cycle is included in all curricula and courses. It seems that people neglect this issue. If you look at the Sustainable Development Goals, sustainable consumption and production, they address how we handle our resources. This is an incredibly important question. If we handle our resources in a good way, we do not have to produce as much new stuff, you save energy. Littering is an effect of unsustainable consumption; it causes micro-plastics to end up in the ocean. If we had circular use of materials, we would solve many other environmental problems, so it is a key issue. It is possible to discuss it on many levels, also in gymnasium. [People say] ‘it is only about recycling’, as if that was an unimportant question. It is an economic issue as well. Some jobs are about mending stuff and renting out stuff, in order to create a circular system. It is very important that you talk about sorting trash in preschool. They [the children] go home and tell their parents, become experts, inspire their parents. Sometimes people talk about it [sustainability] as something very big and complex. Those who try to make it tangible get somewhat downgraded sometimes.”

“When we design lectures, things become very tangible. We try to include components of participation, but in a feasible way. […] Things that are possible to implement. […] In our surveys, we frequently receive answers on participation saying ’well, sort of’. They [the students] have been given a say, in a way, but maybe they did not realize it. They have been given influence to some extent, but they perhaps anticipated that they could decide the course content. But the frames are set and you need to acknowledge that. […] There are course objectives to be met, you are supposed to inspire and coach students to reach the objectives. It is important to use different sorts of working modes. Not only information, but also discussions, questioning and dilemmas—you work in different ways and you participate in the lectures in order to avoid one-way communication all the time. But sometimes, I believe that this [one-way communication] is useful as well. It is a mix.”

“To me, Green Flag is democracy. The Green Flag council is a foundation. Children and teachers decide together—what to do, what to work with. […] The council decides if they want to work with batteries, littering or something else. We work a lot with Agenda 2030 and the SDG’s. Now, it is possible to indicate [in the digital reporting system of the Green Flag] which SDG your work is linked to.”

“What are reasonably boundaries to pluralism? After all, there are facts… Sometimes I feel that you must not forget about the planetary boundaries; they are expressed in the system conditions and so on. Sometimes I feel that the environment is not very prominent in ESD. Other things are important, but it is still the environment and the nature that set limits to what we can do on this globe. It is a basis for me. […] you have to, sort of, understand that you have to do certain things that might feel like sacrifices or conflict ridden.”

“Climate change sceptics are difficult. They are only 2 percent, though… should you always acknowledge all perspectives, even when they are not relevant? That is not realistic, and for how long are we supposed to do it? I would have understood if they [climate change sceptics] constituted 30 percent against 70, but if it is only 2 percent… […] For how long do we include everyone? When have we reached a decision? If you want to bring everyone on board, it takes very long. And it is not certain that people can change.”

“Before the ESE conference in Linköping, we were to plan discussion sessions, and one suggestion for a topic was ‘how can we move from normative and fact-based to pluralistic education?”. But then someone said ‘shouldn’t we ask how to make them complements?’, and that felt liberating. Sometimes it feels like you are absolutely not allowed to talk about fact-based and normative, because everything has to be pluralistic… It has to be mix, it is like… if you have worked in schools you know that it is needed. I think that it is dangerous to run in only one direction. It is important that it [pluralism] has become acknowledged and of course you should work according to pluralism and see that there are no single right answers. You have to be able to discuss and view things from different perspectives and so on, but you have to be able to give a lecture about climate and carbon dioxide as well, how it actually impacts the climate, it is a precondition.”

3.3. Summary of Frame Analysis

- an endorsement of the pluralistic teaching tradition and a strive to reproduce democratic values related to student participation, influence and open-ended discussion, with

- promotion of societal change that in some cases goes beyond development of general agency by defining direction and scope, partly through teaching material that enables normative rather than pluralistic teaching.

- Certain facts or degree of scientific consensus can justify bounding of pluralism by design of ESE, by giving precedence to selected perspectives, downplaying others, or specifying a direction for societal change to be promoted.

- Objectives decided by elected bodies (e.g., curriculum objectives, SDG’s) can justify bounding of pluralism by design of ESE, by defining a content or a direction of societal change to be promoted.

- Decisions taken jointly by student and teacher representatives can justify bounding of pluralism by design of ESE, by defining a content or a direction of societal change to be promoted.

4. Discussion

“deliberative democracy implies in principle (if not in reality) equal citizens, while the participants in deliberative communication in formal educational settings, for example, are teachers and students, that is, individuals with differing knowledge and experience and differences in authority, formal as well as real, deliberating within a ‘weak public.’”[20] (p. 34)

“it is the business of the school environment to eliminate, so far as possible, the unworthy features of the existing environment from influence upon mental habitudes. […] Selection aims not only at simplifying but at weeding out what is undesirable. […] The school has the duty of omitting such things from the environment which it supplies, and thereby doing what it can to counteract their influence in the ordinary social environment. By selecting the best for its exclusive use, it strives to reinforce the power of this best.”(p. 25)

“Once it is understood that some organizational decisions are inevitable, that a form of paternalism cannot be avoided, and that the alternatives to paternalism (such as choosing options to make people worse off) are unattractive, we can abandon the less interesting question of whether to be paternalistic or not, and turn to the more constructive question of how to choose among the possible choice-influencing options.”[41] (p. 1159)

- Epistemic values. Here, knowledge, expertise and/or judgement legitimize that certain people or their views are represented. This source of legitimacy corresponds to justification 1 above, i.e., that views of experts conveyed through teachers and curricula are given precedence over opposing views by non-experts, thereby bounding pluralism.

- Authority or democratic accountability. Here, authorization or political mandate legitimize that certain people and their views are represented. This source of legitimacy can be linked to justification 2 above, i.e., that objectives decided by elected bodies and expressed e.g., in the curriculum or the SDG’s can be used to bound of pluralism. The authority of the teacher to steer the education also draws on this source of legitimacy.

- Presence or shared identity. This source of legitimacy stems from direct presence of groups affected by an issue, or representation of these groups by others with whom they share aspects of identity. To the extent that a sustainability issue affects students and teachers, classroom deliberation in accordance with the pluralistic teaching tradition draws on this source of legitimacy. In terms of bounding of pluralism by design, it can be linked to justification 3, if a student council representing other students through shared identity decide on the scope and content of education.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Wals, A.E.J.; Kronlid, D.; McGarry, D. Transformative, transgressive social learning: Rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 16, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.M. Environment and Environmental Education: Conceptual Issues and Curriculum Implications. Ph.D. Thesis, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Jickling, B.; Spork, H. Education for the Environment: A critique. Environ. Educ. Res. 1998, 4, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fien, J. ‘Education for the Environment: A critique’—An analysis. Environ. Educ. Res. 2000, 6, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stables, A.; Scott, W. The Quest for Holism in Education for Sustainable Development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J. Between knowing what is right and knowing that is it wrong to tell others what is right: On relativism, uncertainty and democracy in environmental and sustainability education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, W.; Van Liedekerke, L.; Van Petegem, P. Higher education for sustainable development in Flanders: Balancing between normative and transformative approaches. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 4622, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. Is Higher Education Ready for Transformative Learning? A Question Explored in the Study of Sustainability. J. Transform. Educ. 2005, 3, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselink, F.; Van Kempen, P.P.; Wals, A.E.J. ESDebate: International Debate on Education for Sustainable Development; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.J. Review of Contexts and Structures for Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kopnina, H. Sustainability in Environmental Education: Away from pluralism and towards solutions. Rebrae 2014, 295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Kopnina, H. Sustainability in environmental education: New strategic thinking. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2015, 17, 987–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, J. Moral perspectives in selective traditions of environmental education—Conditions for environmental moral meaning-making and students’ constitution as democratic citizens. In Learning to Change Our World? Swedish Research on Education & Sustainable Development; Wickenberg, P., Ed.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2004; pp. 33–57. [Google Scholar]

- Englund, T. Deliberative communication: A pragmatist proposal. J. Curric. Stud. 2006, 38, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudsberg, K.; Öhman, J. Pluralism in practice—Experiences from Swedish evaluation, school development and research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englund, T. On moral education through deliberative communication. J. Curric. Stud. 2016, 48, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallace, T. Race, culture, and pluralism: The evolution of Dewey’s vision for a democratic curriculum. J. Curric. Stud. 2012, 44, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzell, C. Towards Deliberative Relationships between Pedagogic Theory and Practice. Nord. Stud. Educ. 2003, 23, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Fritzén, L.; Gustafsson, B. Sustainable development in terms of democracy—An educational challenge for teacher education. In Learning to Change Our World? Swedish Research on Education & Sustainable Development; Wickenberg, P., Axelsson, H., Fritzén, L., Helldén, G., Öhman, J., Eds.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Englund, T.; Öhman, J.; Östman, L. Deliberative communication for sustainability? A Habermas-inspired pluralistic approach. In Sustainability and Security within Liberal Societies: Learning to Live with the Future; Gough, I.S., Stables, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Perspective Transformation. Adult Educ. Q. 1978, 28, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions in Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Fransisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jickling, B.; Wals, A.E.J. Globalization and environmental education: Looking beyond sustainable development. J. Curric. Stud. 2008, 40, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijmbach, S.; Van Arcken, M.M.; Van Koppen, C.S.A. ‘Your View of Nature is Not Mine!’: Learning about pluralism in the classroom. Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildemeersch, D. Displacing concepts of social learning and democratic citizenship. In Civic Learning, Democratic Citizenship and the Public Sphere; Biesta, G., De Bie, M., Wildemeersch, D., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Læssøe, J. Education for sustainable development, participation and socio-cultural change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, F.; Schnack, K. The action competence approach and the “new” discourses of education for sustainable development, competence and quality criteria. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Poeck, K.; Vandenabeele, J. Learning from sustainable development: Education in the light of public issues. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sund, L.; Öhman, J. On the need to repoliticise environmental and sustainability education: Rethinking the postpolitical consensus. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Poeck, K.; Östman, L. Creating space for ‘the political’ in environmental and sustainability education practice: A Political Move Analysis of educators’ actions. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 24, 1406–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, M.; Östman, L.; Van Poeck, K. The political tendency in environmental and sustainability education. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2018, 17, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, M.; Östman, L. The political dimension in ESE: The construction of a political moment model for analyzing bodily anchored political emotions in teaching and learning of the political dimension. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouffe, C. On the Political; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, D. Ecological Literacy: Education and the Transition to a Postmodern World; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.J. Social Learning: Towards a Sustainable World; Wagening Academic: Wagening, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sund, P. Experienced ESD-schoolteachers’ teaching—An issue of complexity. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 21, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, J.; Öhman, M. Participatory approach in practice: An analysis of student discussions about climate change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanen, H. Teachers’ reflections on an education for sustainable development project. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2014, 23, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N. The Adolescent Dip in Students’ Sustainability Consciousness—Implications for Education for Sustainable Development. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 47, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Læssøe, J. Participation and sustainable development: The post-ecologist transformation of citizen involvement in Denmark. Environ. Polit. 2007, 16, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C.R.; Thaler, R.H.; Duchen, C. Libertarian Paternalism is Not an Oxymoron. Univ. Chic. Law Rev. 2003, 70, 1159–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, J. Representing people, representing nature, representing the world. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2001, 19, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grön Flagg—Hållbar Utveckling för Barn Och Unga. Available online: https://www.hsr.se/sites/default/files/gronflagg-broschyr.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- Jidesjö, A. Preparing for Nagoya: The Implementation of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in Sweden; Report Written for the Swedish International Centre of Education for Sustainabile Development: Visby, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pauw, J.; Gericke, N.; Olsson, D.; Berglund, T. The Effectiveness of Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15693–15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A.; Rein, M. Frame Reflection: Toward the Resolution of Intractable Policy Controversies; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, M.A. Deliberative Policy Analysis: Understanding Governance in the Network Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, R. Frame ambiguity in policy controversies: Critical frame analysis of migrant integration policies in Antwerp and Rotterdam. Crit. Policy Stud. 2017, 11, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östman, L.O. Socialisation och Mening: No-Utbildning som Politiskt och Miljömoraliskt Problem. Ph.D. Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Östman, L.; Öhman, J. A transactional approach to learning. Presented at the John Dewey Society Annual Meeting, Denver, CO, USA, 30 April–4 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sandell, K.; Öhman, J.; Östman, L. Education for Sustainable Development: Nature, School and Democracy, 2nd ed.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G. Good Education in an Age of Measurement: On the Need to Reconnect with the Question of Purpose in Education. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 2009, 21, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, E. Transformative Learning: Educational Vision for the 21st Century; Zed Books: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Torbjörnsson, T. Solidaritet och Utbildning för Hållbar Utveckling. En Studie av Förväntningar på och Förutsättningar för Miljömoraliskt Lärande i den Svenska Gymnasieskolan. Ph.D. Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuypers, J.A. Rhetorical Criticism: Perspectives in Action; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vår Filosofi—Handlingskraft & Hållbar Utveckling i Skolan. Available online: www.hsr.se/sites/default/files/omhallbarutveckling.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- Plast i Fisken? Available online: https://www.hsr.se/exempelsamling/plast-i-fisken (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- Framtidsfrågor i Klassrummet. Klimat & Energi. En Didaktisk Vägledning för åk 4-9. Available online: https://www.hsr.se/sites/default/files/didaktiskhandledning.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- Kopnina, H. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD): The turn away from “environment” in environmental education? Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, T.; Goeminne, G.; Van Poeck, K. Balancing the urgency and wickedness of sustainability challenges: Three maxims for post-normal education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 1424–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennbeck, M. Omsorg om Naturen: Om NO-Utbildningens Selektiva Traditioner med Fokus på Miljöfostran och Genus. Ph.D. Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Molin, L. Rum, Frirum och Moral: En Studie av Skolgeografins Innehållsval. Ph.D. Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, B. Undersökningar av Sociovetenskapliga Samtal i Naturvetenskaplig Utbildning. Ph.D. Thesis, Linnaeus University, Växjö/Kalmar, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hedefalk, M. Förskola för Hållbar Utveckling: Förutsättningar för Barns Utveckling av Handlingskompetens för Hållbar Utveckling. Ph.D. Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson, M.; Kronlid, D.O.O.; Östman, L. Searching for the political dimension in education for sustainable development: Socially critical, social learning and radical democratic approaches. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 4622, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronlid, D.O. Skolans Värdegrund 2.0. Etik för en Osäker Tid; Natur & Kultur: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Öhman, J. Pluralism and criticism in environmental education and education for sustainable development: A practical understanding. Environ. Educ. Res. 2006, 12, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J. Between Naturalism and Religion: Philosophical Essays; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actual existing democracy. In Habermas and the Public Sphere; Calhoun, C., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993; pp. 109–142. [Google Scholar]

- Sund, P.; Lysgaard, J.G. Reclaim “education” in environmental and sustainability education research. Sustainability 2013, 5, 1598–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Mougan, C.M.; Nussbaum, J. Dewey and Education for Democratic Citizenship. Pragmatism Today 2013, 4, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein, C. The Ethics of Nudging. Yale J. Regul. Artic. 2015, 32, 413–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedwell, C. Habit and the Politics of Social Change: A Comparison of Nudge Theory and Pragmatist Philosophy. Body Soc. 2017, 23, 59–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, T.E. Discussing controversial issues: Four perspectives on the teacher’s role. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 1986, 14, 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, S.; Richardson, T.; Miles, T. Situated legitimacy: Deliberative arenas and the new rural governance. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hellquist, A.; Westin, M. On the Inevitable Bounding of Pluralism in ESE—An Empirical Study of the Swedish Green Flag Initiative. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072026

Hellquist A, Westin M. On the Inevitable Bounding of Pluralism in ESE—An Empirical Study of the Swedish Green Flag Initiative. Sustainability. 2019; 11(7):2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072026

Chicago/Turabian StyleHellquist, Alexander, and Martin Westin. 2019. "On the Inevitable Bounding of Pluralism in ESE—An Empirical Study of the Swedish Green Flag Initiative" Sustainability 11, no. 7: 2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072026

APA StyleHellquist, A., & Westin, M. (2019). On the Inevitable Bounding of Pluralism in ESE—An Empirical Study of the Swedish Green Flag Initiative. Sustainability, 11(7), 2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072026