The National Parks in the Context of Tourist Function Development in Territorially Linked Municipalities in Poland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Tourist Function vs. Environment Protection—Literature Review

3. Methodology

- the characteristics of national parks’ area sharing function and nature education function,

- the characteristics of nature protection function transformations in the municipalities territorially linked with national parks,

- the characteristics of tourist function transformations in the municipalities territorially linked with national parks,

- the assessment of correlation between nature protection function and tourism development in municipalities.

- defining variables (indicators) for each SDM,

- carrying out the unitarization with zero minimum procedure for the entire period simultaneously (2001–2016),

- SDM construction with a weight system in accordance with the method of (standardized) sums with a common development pattern for the years 2001–2016,

- defining the ranking position of municipalities in each of the analyzed years for the particular SDM (SDMprot, SDMtur),

- comparing the ranking positions of municipalities defined by each SDM (SDMprot, SDMtur),

- comparing changes of the situation in a municipality over time based on SDMprot, SDMtur,

- calculating the sequence correlation coefficient between SDMprot and the supplemented SDMtur measure,

- grouping of municipalities according to SDM value (SDMprot, SDMtur) using arithmetic mean and standard deviation.

- share of national parks’ area in the area of a municipality (gmina) (NP share),

- share of landscape parks’ area in the area of a municipality (gmina) (LP share),

- share of protected landscape areas in the area of a municipality (gmina) (Protl share).

- class A (the highest activity level)

- class B (medium higher activity level)

- class C (medium lower activity level)

- class D (lower activity level)notes:

- SDM—synthetic development measure value (SDMprot, SDMtur) for municipalities,

- —arithmetic mean of the synthetic development measure value (SDMprot, SDMtur),

- —standard deviation of the synthetic development measure value (SDMprot, SDMtur).

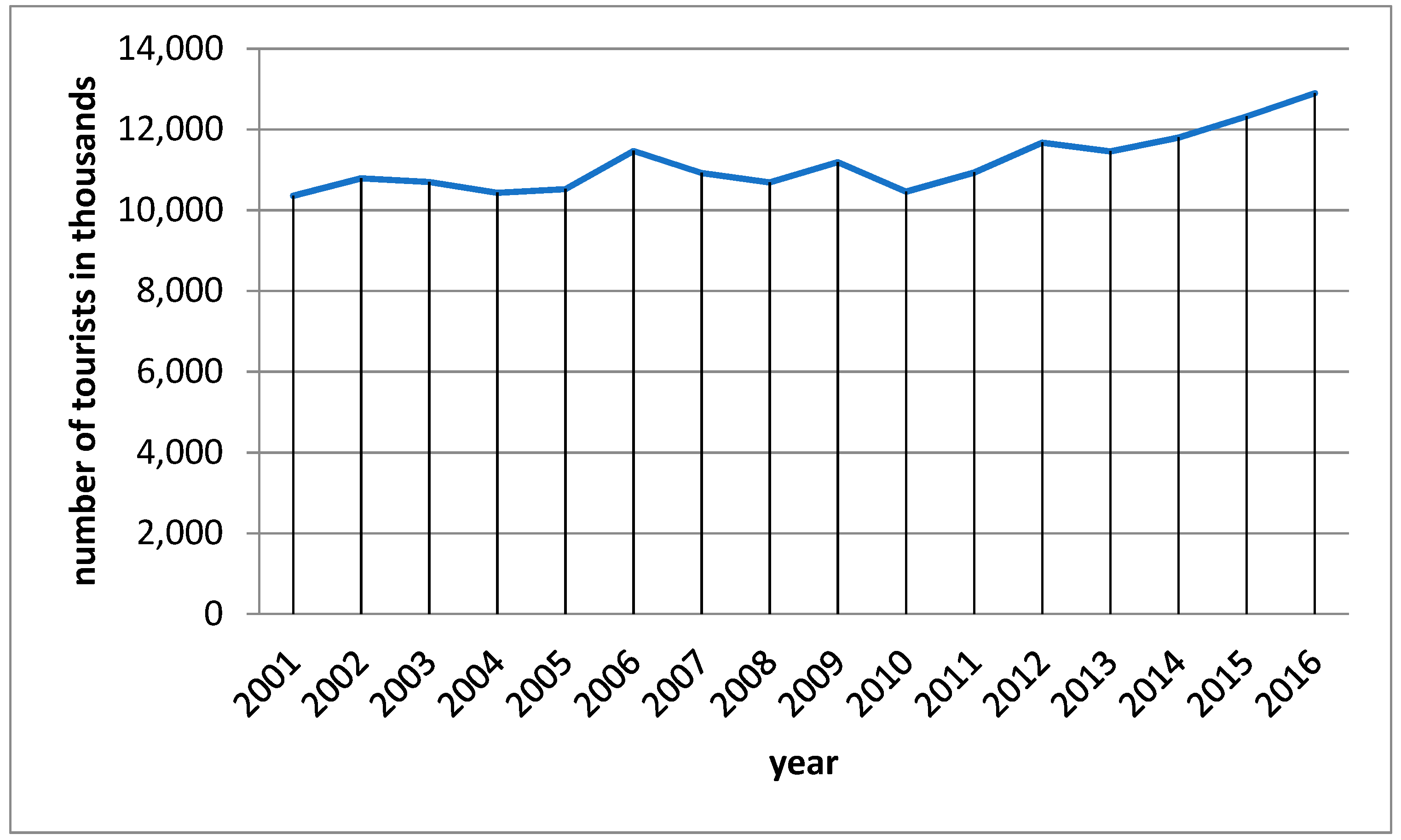

4. The Function of Land Sharing and the Function of Nature Education in National Parks

5. The Level and Transformations of both Nature Protection Function and Tourist Function in the Municipalities Territorially Linked with National Parks

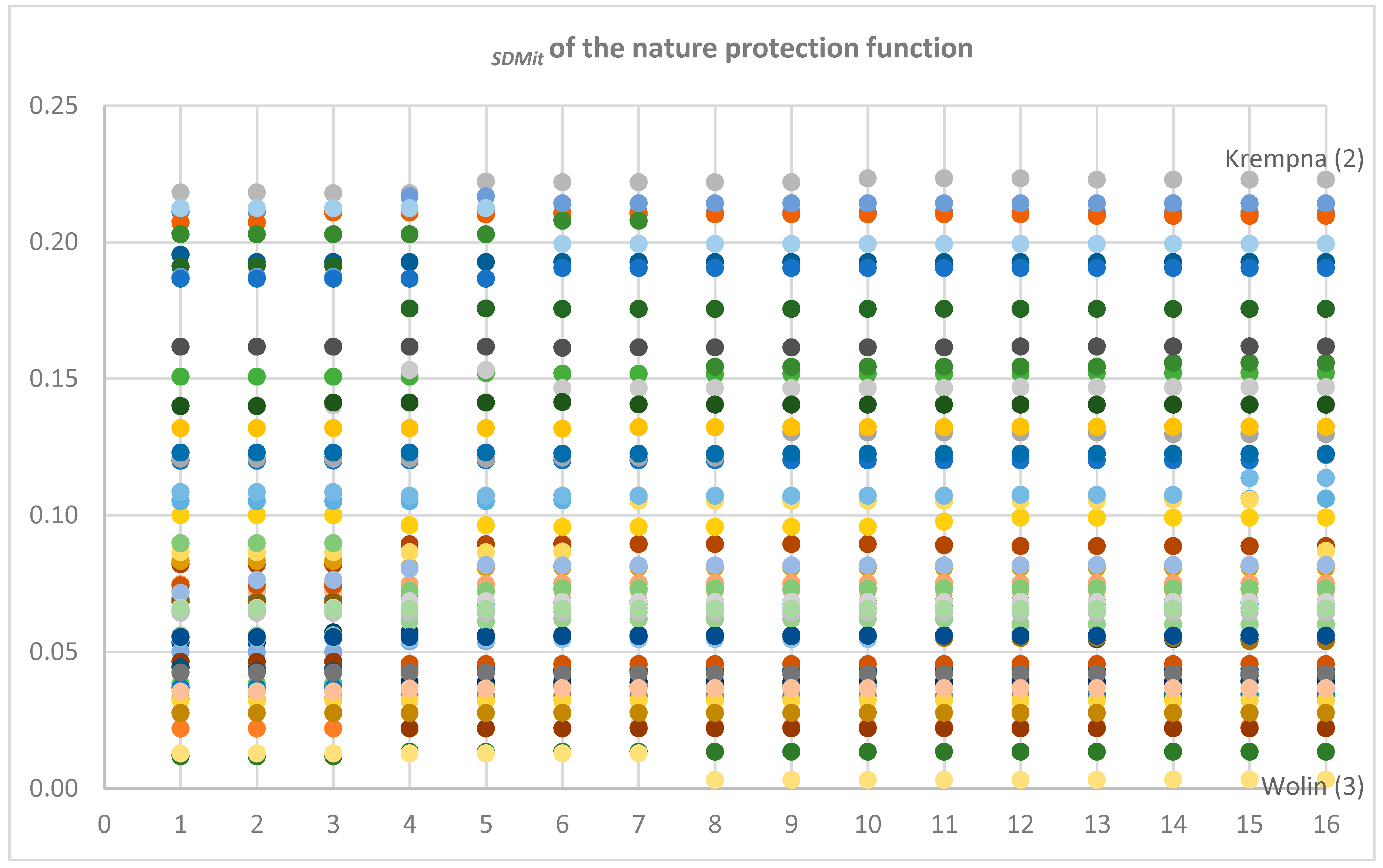

5.1. The Characteristics of SDM Values’ Diversification

5.2. Nature Protection Function Transformations in the Municipalities Territorially Linked with National Parks

- Biebrza—Goniądz Municipality,

- Bieszczady—Lutowiska Municipality,

- Kampinos—Izabelin Municipality,

- Leoncin Municipality,

- Leszno Municipality (in the years 2008–2015),

- Karkonosze—Karpacz Municipality (in the years 2001–2003),

- Magura—Krempna Municipality,

- Roztocze—Zwierzyniec Municipality,

- Słowiński—Smołdzino Municipality (in the years 2004–2016),

- Tatra—Zakopane Municipality,

- Kościelisko Municipality,

- Wolin—Międzyzdroje Municipality (in the years 2001–2007).

- Babia Góra: Jabłonka Municipality, Lipnica Wielka Municipality,

- Biebrza: Radziłów Municipality, Nowy Dwór Municipality,

- Bieszczady: Ustrzyki Dolne Municipality,

- Drawno: Dobiegniew Municipality,

- Gorce: Nowy Targ Municipality,

- Magura: Sękowa Municipality,

- Pieniny: Czorsztyn Municipality,

- Słowiński: Smołdzino Municipality, Główczyce Municipality,

- Słowiński: Ustka Municipality,

- Świętokrzyski: Górno Municipality, Bieliny Municipality.

- Biebrza: Jedwabne Municipality, Wizna Municipality,

- Karkonosze: Karpacz Municipality, Jelenia Góra Municipality, Kowary Municipality, Szklarska Poręba Municipality, Podgórzyn Municipality, Piechowice Municipality,

- Ojców: Skała Municipality,

- Pieniny: Szczawnica Municipality

- Wolin: Międzyzdroje Municipality, Wolin Municipality.

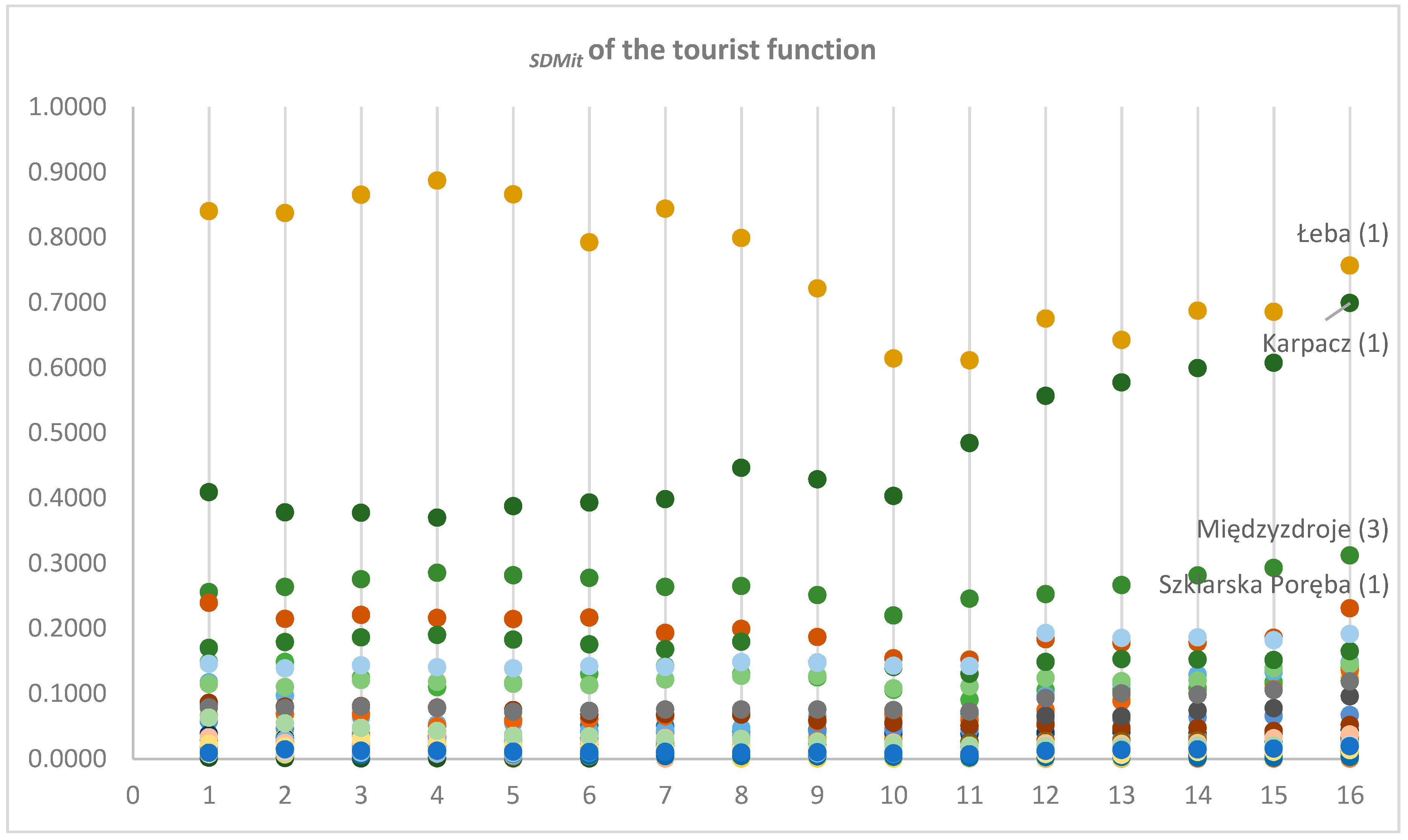

5.3. Tourist Function Transformations in the Municipalities Territorially Linked with National Parks

- Białowieża—Białowieża Municipality (2010–2011; 2013–2014),

- Bieszczady—Cisna Municipality, Lutowiska Municipality (2008; 2016),

- Stołowe Mountains—Kudowa Zdrój Municipality (2001–2002, 2009, 2012–2016),

- Karkonosze—Karpacz Municipality, Podgórzyn Municipality (2001–2007), Szklarska Poręba Municipality,

- Pieniny—Szczawnica Municipality,

- Słowiński—Łeba Municipality, Ustka Municipality,

- Tatra—Bukowina Tatrzańska Municipality (2012; 2015), Zakopane Municipality,

- Wolin—Międzyzdroje Municipality, Świnoujście Municipality (2003–2011).

6. The Relationship between Nature Protection Function and Tourist Function in the Municipalities Territorially Linked with National Parks

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Runte, A. National Parks: The American Experience; University of Nebraska Press: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, D.; Upadhyay, V.; Puri, B. Tourism at Protected Areas: Sustainability or Policy Crunch? IIM Kozhikode Soc. Manag. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilg, A. Tourism and National Parks: International perspectives on development, histories and change. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 12, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall Reinius, S.; Fredman, P. Protected Areas as attractions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 839–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP-WCMC and IUCN. Protected Planet Report 2016; UNEP-WCMC and IUCN: Cambridge, UK; Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, A. Geografia Turyzmu/Geography of Tourism; PWN Publishers: Warsaw, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baretje, R.; Defert, P. Aspects Economiques du Tourisme; Berger-Levrault: Paris, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Charvat, J.; Cerny, B. Untraditionelle Elemente bei der Erfassung der Fermdenverkehrsintensitat. Zeitschrift fur den Fremdenverkehr 1960, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Menges, G. Methoden und Probleme der Deutschen Fremdenverkehrsstatistik; Schriftenreihe des Instituts fur Fremdenverkehrswissenschaft; Goethe Uniwersitaet: Frankfurt, Germany, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Warszyńska, J.; Jackowski, A. Podstawy Geografii Turyzmu/Basics in Tourism Geography; PWN Publishers: Warsaw, Poland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Lijewski, T.; Mikułowski, B.; Wyrzykowski, J. Geografia Turystyki Polski/Geography of Polish Tourism; PWE Publishers: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, T.M.; Mittermeier, R.A.; da Fonseca, G.A.; Gerlach, J.; Hoffmann, M.; Lamoreux, J.F.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Pilgrim, J.D.; Rodrigues, A.S. Global Biodiversity Conservation Priorities. Science 2006, 313, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P.F.J.; McCool, S.F.; Haynes, C.D.A. Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas: Guidelines for Planning and Management; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, W.M.; Aveling, R.; Brockington, D.; Dickson, B.; Elliott, J.; Hutton, J.; Roe, D.; Vira, B.; Wolmer, W. Biodiversity Conservation and the Eradication of Poverty. Science 2004, 306, 1145–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Redford, K. Poverty, Development and Biodiversity Conservation: Shooting in the Dark? Working Paper No. 26; Wildlife Conservation Society: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISSN 1534-7389. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, C.B.; Travis, A.J.; Dasgupta, P. On biodiversity conservation and poverty traps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 13907–13912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McShane, T.O.; Hirsch, P.D.; Trung, T.C.; Songorwa, A.N.; Kinzig, A.; Monteferri, B.; Mutekanga, D.; Van Thang, H.; Dammert, J.L.; Pulgar-Vidal, M.; et al. Hard choices: Making trade-offs between biodiversity conservation and human well-being. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Act of April 16, 2004 on Nature Conservation Journal of Laws of 2004; No. 92, item 880, as amended; 2004, Poland.

- Żarska, B. Ochrona Krajobrazu/Landscape Protection; Warsaw University of Life Sciences—SGGW Press: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Heilig, G.K. Multifunctionality of landscapes and ecosystem services with respect to rural development. In Sustainable Development of Multifunctional Landscapes; Helming, K., Wiggering, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bielińska, E.J.; Futa, B.; Baran, S.; Żukowska, G.; Pawłowska, M.; Cel, W.; Zhang, T. Integrująca rola paradygmatu zrównoważonego rozwoju w kształtowaniu relacji człowiek-krajobraz/Integrating role of sustainable development paradigm in developing the relationship human being-landscape. Problemy ekorozowju/Problems of Sustainable development. Jelenia Góra-Białystok 2015, 10, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Chiesura, A.; de Groot, R. Critical natural capital: A socio-cultural perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 44, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, P. Assessing changes in high-value landscape—Case study of the municipality of Sobotka in Poland. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 26, 2603–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczyk-Dynowska, A. Parki Narodowe a Funkcje Turystyczne i Gospodarcze Gmin Terytorialnie Powiązanych [National Parks vs. Tourist and Economic Functions of the Territorially Linked Municipalities]; Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences Press: Wrocław, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Donohoe, H.M.; Needham, R.D. Ecotourism: The evolving contemporary definition. J. Ecotour. 2006, 5, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Ecotourism Society. What is Ecotourism? 2019. Available online: http://www.ecotourism.org (accessed on 22 February 2019).

- Wight, P.A. Supporting the principles of sustainable development in tourism and ecotourism: Government’s potential role. Curr. Issues Tour. 2002, 5, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Tourism Highlights. 2018. Available online: www.eunwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284419876 (accessed on 22 February 2019).

- Martins, L.; Gan, Y.; Ferreira-Lopes, A. An empirical analysis of the influence of macroeconomic determinants on World tourism demand. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, J.; Kourtit, K.; Neuts, B.; Nijkamp, P. The smart city as a common place for tourists and residents: A structural analysis of the determinants of urban attractiveness. Cities 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hernández, M.; de la Calle-Vaquero, M.; Yubero, C. Cultural heritage and urban tourism: Historic city centres under pressure. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, L.; Vargas-Sanchez, A. (Eds.) Strategic Management in Tourism; CABI Tourism Texts; CABI: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhove, N. The Economics of Tourism Destinations: Theory and Practice; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, H. Local community involvement in tourism around national parks: Opportunities and constraints. Curr. Issues Tour. 2002, 5, 338–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M. Can nature-based tourism benefits compensate for the costs of national parks? A study of the Bavarian Forest National Park, Germany. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, A.H. How Conceptions of Equity and Justice Shape National Park Negotiations: The Case of Parc Adula. Available online: http://epub.oeaw.ac.at/eco.mont (accessed on 22 February 2019).

- McNeely, J.A.; Harrison, J.; Dongwall, P. Protected Areas in the Modern World. In Protecting Nature: Regional Reviews of Protected Areas, IVth World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas; McNeely, J.A., Harrison, J., Dongwall, P., Eds.; IUCN Publications Services Unit.: Caracas, Venezuela, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McNeely, J.A.; Miller, K. National parks, conservation, and development: The role of protected areas in sustaining society. In Proceedings of the World Congress on National Parks, Bali, Indonesia, 11–22 October 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, A. The environment—Tourism nexus influence of market ethics. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poskrobko, B.; Poskrobko, T. Zarządzanie Środowiskiem w Polsce/Environment Management in Poland; PWE Publishers: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocka-Grześkowiak, U. Rozwój turystyki na Półwyspie Helskim i jej skutki/The development of tourism on Hel Peninsula and its effects. Probl. J. Agric. Sci. Prog. 2011, 564, 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, R. Will tourists pay for a healthy environment? Assessing visitors’ perceptions and willingness to pay for conservation and preservation in the island of Koh Phi Phi, Thailand. Int. J. Tour. Anthropol. 2013, 3, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, J.; van Hoof, J.; Szewrański, S. Challenges in the wind turbines location process in Central Europe—The use of spatial decision support systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewrański, S.; Kazak, J.; Żmuda, R.; Wawer, R. Indicator-Based Assessment for Soil Resource Management in the Wrocław Larger Urban Zone. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 26, 2239–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świgost, A. The transformation of the natural environment of the Polish and Ukrainian Bieszczady mountains due to tourism and other forms of human pressure. Curr. Issues Tour. Res. 2015, 5, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sakellari, M.; Skanavis, C. Sustainable tourism development: Environmental education as a tool to fill the gap between theory and practice. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krukowska, R.; Świeca, A.; Tucki, A. Kim jest turysta w paku narodowym?/Who is a tourist in a national park. Workshops Geogr. Tour. 2016, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Martín, J.M.; Rengifo Gallego, J.I.; Martín Delgado, L.M. Tourist Mobility at the Destination Toward Protected Areas: The Case-Study of Extremadura. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płuciennik, M.; Hełdak, M.; Werner, E.; Szczepański, J.; Patrzałek, C. Using the Laser Technology in Designing Land Use. In Landscape and Landscape Ecology. In Proceedings of the 17th International Symposium on Landscape Ecology, Nitra, Slovakia, 27–29 May 2015; pp. 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Krajewski, P. Problemy Planistyczne na Terenach Parków Krajobrazowych w Sąsiedztwie Wrocławia/Planning Problems in the Area of Landscape Parks in the Vicinity of Wrocław; Research Papers of Wrocław University of Economics: Wrocław, Poland, 2014; Volume 37, pp. 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Hummel, C.; Poursanidis, D.; Orenstein, D.; Elliott, M.; Adamescu, M.C.; Cazacu, C.; Ziv, G.; Chrysoulakis, N.; der Meer, J.; Hummel, H. Protected Area management: Fusion and confusion with the ecosystem services approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2432–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, K. Speaking a Common Language: The Uses and Performance of the IUCN System of Management Categories for Protected Areas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig, Z. Zastosowanie metody taksonomicznej do typologicznego podziału krajów ze względu na poziom ich rozwoju oraz zasoby i strukturę wykwalifikowanych kadr/The application of taxonomic method in the typological division of countries regarding their development level and resources and structure of qualified personnel. Stat. Rev. 1968, 4, 307–327. [Google Scholar]

- Strahl, D. Propozycja konstrukcji miary syntetycznej/The proposal of statistical measure construction. Stat. Rev. 1978, 25, 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Walesiak, M. Uogólniona Miara Odległości w Statystycznej Analizie Wielowymiarowej/Generalized Distance Measure in a Statistical Multidimensional Analysis; University of Economics in Wrocław Press: Wrocław, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marti, R.; Reinelt, G. The Linear Ordering Problem, Exact and Heuristic Methods in Combinatorial Optimization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kukuła, K. Propozycja Budowy Rankingu Obiektów z Wykorzystaniem cech Ilościowych oraz Jakościowych [Proposal of Ranking Construction on the Basis of Quantitative and Qualitative Variables], Metody Ilościowe w Badaniach Ekonomicznych [Quantitative Methods in Economic Research]; Issue XIII/2012; SGGW Press: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; pp. 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kukuła, K. Zero unitarisation metod as a tool in ranking research. Econ. Sci. Rural Dev. 2014, 36, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bal-Domańska, B. Propozycja procedury oceny zrównoważonego rozwoju w układzie presja—Stan—Reakcja w ujęciu przestrzennym/The proposal of sustainable development assessment procedure from the perspective of pressure—State—Reaction in the spatial arrangement. In Taksonomia, Klasyfikacja i Analiza Danych—Teoria i Zastosowania/Taxonomy, Classification and Data Analysis—Theory and Applications; No. 427; Jajuga, K., Walesiak, M., Eds.; Research Papers of Wrocław University of Economics: Wrocław, Poland, 2016; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kukuła, K.; Luty, L. Jeszcze o procedurze wyboru metody porządkowania liniowego [Once More about the Selection Procedure for the Linear Ordering Method]. Stat. Rev. 2017, 64, 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Manly, B.F.J.; Navarro Alberto, J.A. Multivariate Statistical Methods; CRC Press Taylor& Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bal-Domańska, B. Ocena zrównoważonego rozwoju Polski w układzie powiatów w ujęciu przyczyna—Stan—Reakcja. Przypadek bezrobocie—Ubóstwo—Aktywność gospodarcza/The assessment of sustainable development of Poland in the system of counties from the perspective of cause—State—Reaction. The case of unemployment—Poverty—Economic activity. In Gospodarka Regionalna w Teorii i Praktyce/Regional Economy in Theory and Practice; No. 433; Research Papers of Wrocław University of Economics: Wrocław, Poland, 2016; pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Malina, A. Analiza Przestrzennego Zróżnicowania Poziomu Rozwoju Społeczno-Gospodarczego Powiatów Województwa Małopolskiego w Latach 2000–2004/The Analysis of Spatial Diversification of Socio-Economic Development Level of Counties in Małopolskie Region in the Years 2000–2004; Research Journals of Cracow University of Economics. No. 797; Cracow University of Economics Press: Cracow, Poland, 2008; pp. 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Spearman, C. The Proof and Measurement of Association between Two Things. Am. J. Psychol. 1904, 15, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. Notes on regression and inheritance in the case of two parents. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1895, 58, 240–242. [Google Scholar]

- Sobczyk, M. Statystyka Opisowa/Descriptive Statistics; C.H. Beck Publishers: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kulczyk-Dynowska, A. The spatial and financial aspects of protected areas using the example of the Babia Góra National Park. In Hradec Economic Days 2014, Economic Development and Management of Regions, Peer-Reviewed Conference Proceedings; Part IV; Fakulta Informatiky a Management, Univerzita Hradec Kralove: Králové, Czech Republic, 2014; pp. 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kulczyk-Dynowska, A. Space protected through competition as exemplified by the Tatra National Park. In Hradec Economic Days 2015, Economic Development and Management of Regions, Peer-Reviewed Conference Proceedings; Part IV; Fakulta Informatiky a Management, Univerzita Hradec Kralove: Králové, Czech Republic, 2015; pp. 322–330. [Google Scholar]

- Borys, T. Edukacja dla zrównoważonego rozwoju/Education for sustainable development. In Edukacja dla Zrównoważonego Rozwoju/Education for Sustainable Development; Borys, T., Ed.; Economics and Environment Publishers: Białystok, Poland, 2006; Volume I, pp. 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Borys, T. Zrównoważony rozwój jako wyzwanie edukacyjne/Sustainable development as the educational challenge. In Edukacja dla Zrównoważonego Rozwoju/Education for Sustainable Development; Borys, T., Ed.; Economics and Environment Publishers: Wrocław, Poland, 2010; Volume I, pp. 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Szromek, A. Przegląd wskaźników funkcji turystycznej i ich zastosowanie w ocenie rozwoju turystycznego obszaru na przykładzie gmin województwa śląskiego/The review of tourist function indicators and their application in the assessment of area tourism development, the case of Silesia Region municipalities. In Research Journals of the Silesian University of Technology, Series: Organization and Mangement No. 61; Silesian University of Technology Press: Gliwice, Poland, 2012; pp. 295–309. [Google Scholar]

- Symonides, E. Ochrona Przyrody/Nature Conservation; Warsaw University Press: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kulczyk-Dynowska, A. Rozwój Regionalny na Obszarach Chronionych, [Regional Development in Protected Areas]; Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences Press: Wrocław, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Burzyńska, D. Rola Inwestycji Ekologicznych w Zrównoważonym Rozwoju Gmin w Polsce, [The Role of Environmental Investments in the Sustainable Development of Municipalities in Poland]; University of Lodz Press: Łódź, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Raszkowski, A.; Bartniczak, B. Sustainable Development in the Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs): Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raszkowski, A.; Bartniczak, B. On the Road to Sustainability: Implementation of the 2030 Agenda Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepiora, Z.; Kachniarz, M.; Babczuk, A. Active Natural Disasters Policy in Poland. International Conference on Intelligent Control and Computer Application (ICCA 2016); Atlantis Press: Paris, France; Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Hong Kong, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stacherzak, A.; Hełdak, M. Borough Development Dependent on Agricultural, Tourism, and Economy Levels. Sustainability 2019, 11, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siewe, S.; Vadjunec, J.M.; Caniglia, B. The Politics of Land Use in the Korup National Park. Land 2017, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.P.; McShane, T.O. Integrating protected area management with local needs and aspirations. Ambio A J. Hum. Environ. 2004, 33, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.P.; McShane, T.O.; Dublin, H.T.; O’Connor, S.; Redford, K.H. The future of integrated conservation and development projects: Building on what works. In Getting Biodiversity Projects to Work: Towards More Effective Conservation and Development; McShane, T.O., Wells, M.P., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 397–421. [Google Scholar]

- Garnett, S.; Sayer, J.; Du Toit, J. Improving the effectiveness of interventions to balance conservation and development: A conceptual framework. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.; Flintan, F. Integrating Conservation and Development Experience: A Review and Bibliography of the ICDP Literature, Biodiversity and Livelihoods; Issues No. 3; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Getzner, M.; Svajda, J. Preferences of tourists with regard to changes of the landscape of the Tatra National Park in Slovakia. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| National Park | Visitors | Environmental Education | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourists in Thousands | Position | Visitors to Educational Sites in Thousands | Position | |

| Babiogóra | 1131 | 15 | 171 | 15 |

| Białowierza | 2471 | 12 | 1205 | 3 |

| Biebrza | 555 | 19 | 169 | 16 |

| Bieszczady | 5350 | 8 | 430 | 9 |

| Tuchola Forest | 694 | 18 | 0 | 23 |

| Drawno | 325 | 22 | 1 | 22 |

| Gorce | 980 | 16 | 96 | 19 |

| Stołowe Mountains | 5326 | 9 | 153 | 18 |

| Kampinos | 15,400 | 5 | 464 | 7 |

| Karkonosze | 29,500 | 2 | 356 | 12 |

| Magura | 768 | 17 | 205 | 13 |

| Narew | 156 | 23 | 93 | 20 |

| Ojców | 6328 | 7 | 391 | 10 |

| Pieniny | 11,789 | 6 | 5896 | 1 |

| Polesie | 351 | 21 | 190 | 14 |

| Roztocze | 1766 | 13 | 455 | 8 |

| Słowiński | 4618 | 10 | 482 | 6 |

| Świętokrzyski | 3171 | 11 | 956 | 4 |

| Tatra | 42,304 | 1 | 1290 | 2 |

| Warty Mouth | 443 | 20 | 85 | 21 |

| Wielkopolska | 19,200 | 4 | 167 | 17 |

| Wigry | 1730 | 14 | 381 | 11 |

| Wolin | 24,300 | 3 | 607 | 5 |

| Specification | Number of Municipalities | |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2016 | |

| Class A—the highest activity level of protection function | 19 | 21 |

| Class B—medium higher activity level of protection function | 23 | 23 |

| Class C—medium lower activity level of protection function | 61 | 60 |

| Class D—lower activity level of protection function | 14 | 13 |

| Specification | Number of Municipalities | |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2016 | |

| Class A—the highest activity level of tourism function | 4 | 4 |

| Class B—medium higher activity level of tourism function | 9 | 10 |

| Class C—medium lower activity level of tourism function | 42 | 41 |

| Class D—lower activity level of tourism function | 0 | 0 |

| National Park | Name of the Municipality |

|---|---|

| Babia Góra | Jabłonka (2), Lipnica Wielka (2), |

| Biebrza | Bargłów Kościelny (2), Sztabin (2), Grajewo (2), Jedwabne (3), Wizna (2), Jaświły (2), Trzcianne (2), Dąbrowa Białostocka (3), Suchowola (3), Lipsk (3), Radziłów (2), Nowy Dwór (2), |

| Tuchola Forest | Brusy (3), |

| Drawno | Człopa (3), Dobiegniew (3), Krzyż Wielkopolski (3), |

| Gorce | Kamienica (2), Nowy Targ (2), |

| Kampinos | Czosnów (2), Leoncin (2), Brochów (2), Kampinos (2), Leszno (2), Łomianki (3), Stare Babice (2), Izabelin (2), |

| Karkonosze | Jelenia Góra (1), |

| Magura | Dębowiec (2), Nowy Żmigród (2), Dukla (3), Lipinki (2), Osiek Jasielski (2), Sękowa (2), |

| Narew | Choroszcz (3), Łapy (3), Turośń Kościelna (2), Tykocin (3), Kobylin Borzymy (2), Sokoły (2), |

| Ojców | Jerzmanowice-Przeginia (2), Skała (3), Sułoszowa (2), |

| Polesie | Stary Brus (2), Wierzbica (2), Hańsk (2), |

| Roztocze | Józefów (3), Zamość (2), Adamów (2), |

| Słowiński | Główczyce (2), |

| Świętokrzyski | Bieliny (2), Górno (2), Łączna (2), |

| Warty Mouth | Kostrzyn nad Odrą (1), Witnica (3), Górzyca (2), |

| Wielkopolska | Komorniki (2), Mosina (3), Puszczykowo (1), Dopiewo (2), |

| Wigry | Krasnopol (2), |

| National Park | SDMprot Ranking (*) | SDMtur Ranking (*) |

|---|---|---|

| Białowieża | x | Białowieża (2010–2011; 2013–2014) |

| Biebrza | Goniądz | x |

| Bieszczady | Lutowiska | Cisna Lutowiska (2008; 2016) |

| Stołowe Mountains | x | Kudowa Zdrój (2001–2002; 2009; 2012–2016) |

| Kampinos | Izabelin, Leoncin, Leszno (2008–2015) | x |

| Karkonosze | Karpacz (2001–2003) | Szklarska Poręba Podgórzyn (2001–2007) Karpacz |

| Magura | Krempna | x |

| Pieniny | x | Szczawnica |

| Roztocze | Zwierzyniec | x |

| Słowiński | Smołdzino (2004–2016) | Łeba Ustka |

| Tatra | Zakopane Kościelisko | Zakopane Bukowina Tatrzańska (2012; 2015) |

| Wolin | Międzyzdroje (2001–2007) | Świnoujście (2003–2011) Międzyzdroje |

| Specification | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| SMRtur and SMRprot | ||||||||||||||||

| Spearman | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.29 |

| Pearson | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Charvat index and SMRprot | ||||||||||||||||

| Spearman | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.27 |

| Pearson | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.24 |

| p-value | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kulczyk-Dynowska, A.; Bal-Domańska, B. The National Parks in the Context of Tourist Function Development in Territorially Linked Municipalities in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071996

Kulczyk-Dynowska A, Bal-Domańska B. The National Parks in the Context of Tourist Function Development in Territorially Linked Municipalities in Poland. Sustainability. 2019; 11(7):1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071996

Chicago/Turabian StyleKulczyk-Dynowska, Alina, and Beata Bal-Domańska. 2019. "The National Parks in the Context of Tourist Function Development in Territorially Linked Municipalities in Poland" Sustainability 11, no. 7: 1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071996

APA StyleKulczyk-Dynowska, A., & Bal-Domańska, B. (2019). The National Parks in the Context of Tourist Function Development in Territorially Linked Municipalities in Poland. Sustainability, 11(7), 1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071996