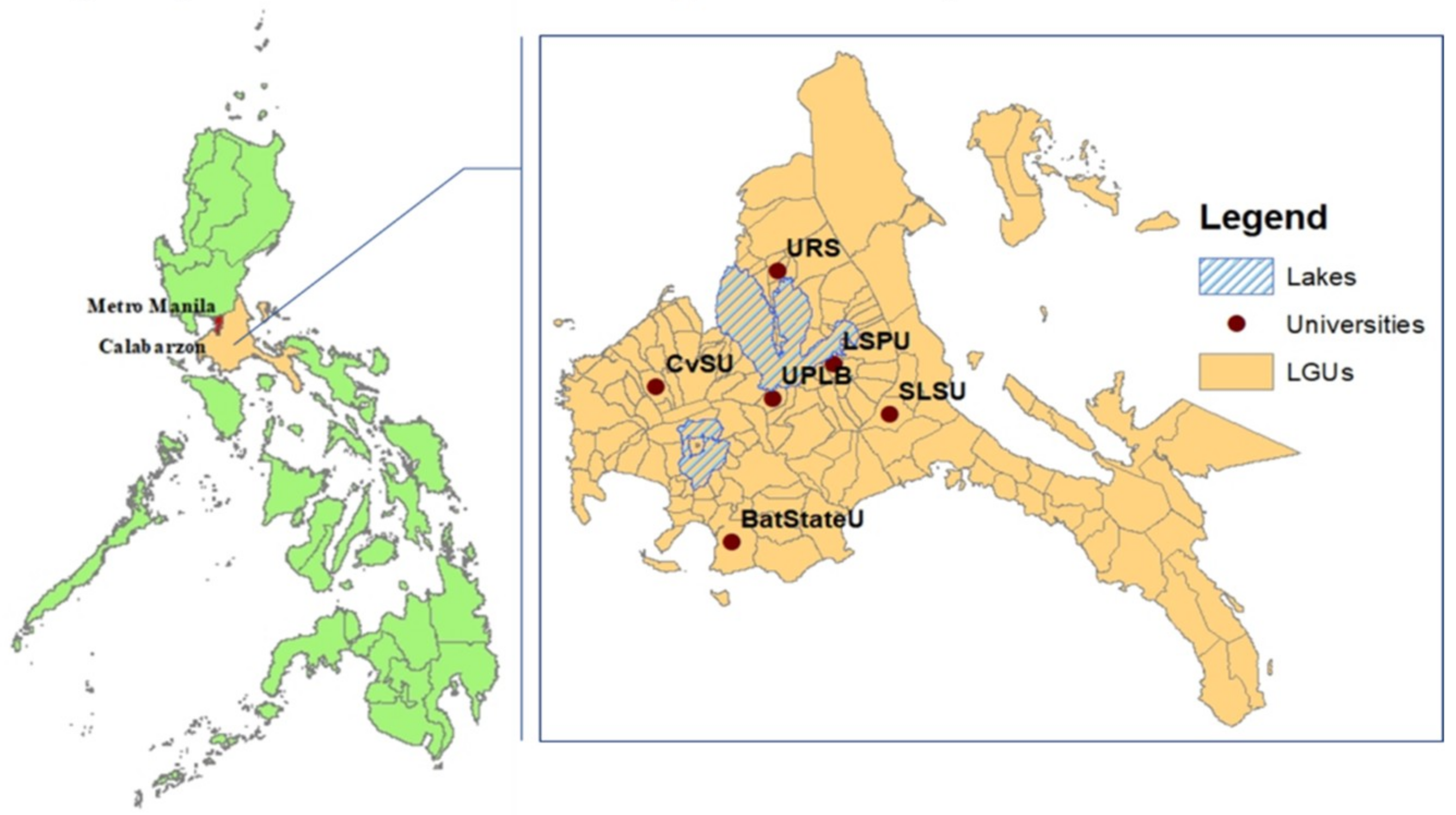

University-Community Partnerships: A Local Planning Co-Production Study on Calabarzon, Philippines

Abstract

:1. Introduction

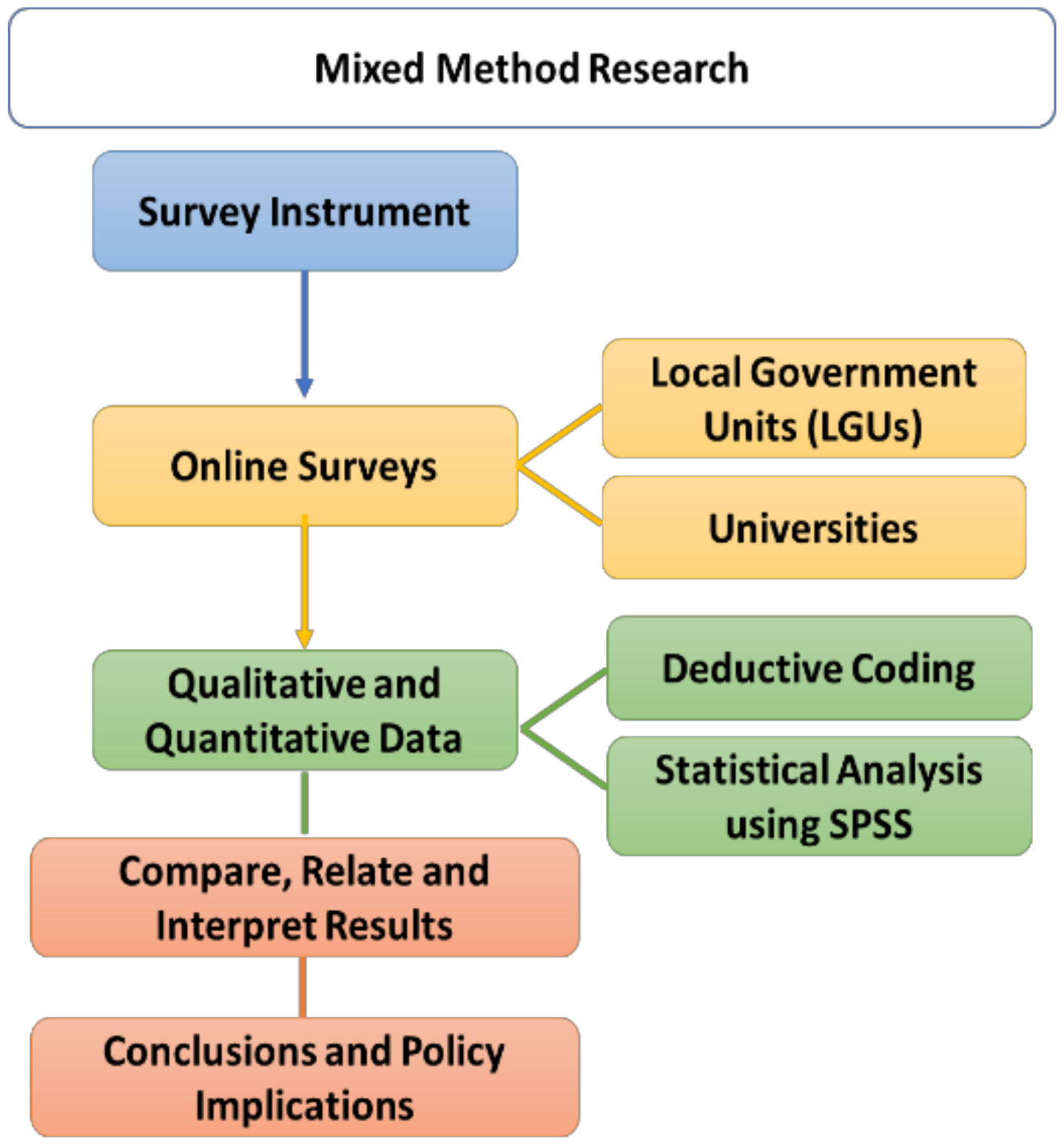

2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

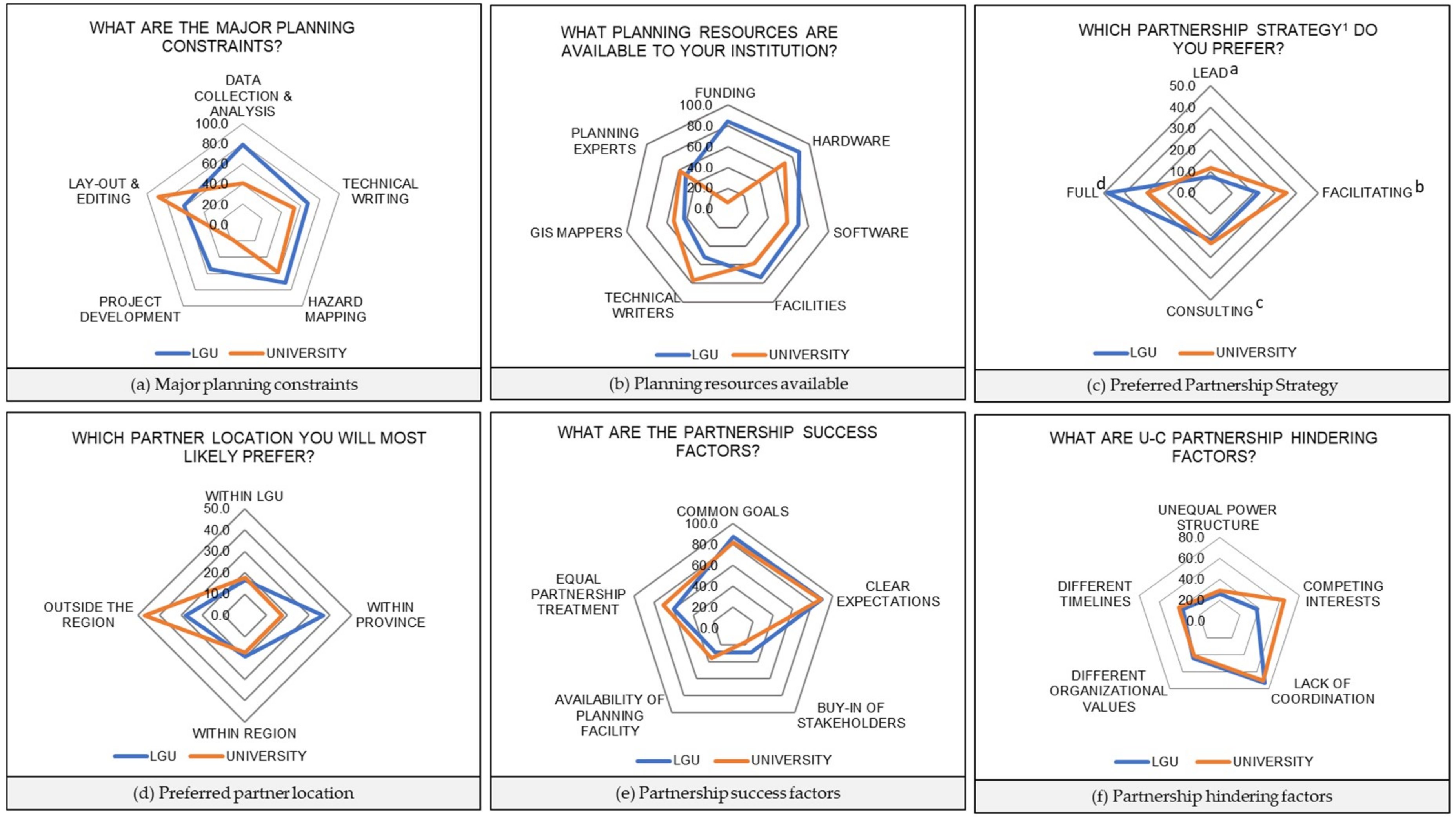

3.1. Assessment of Needs, Resources, and Partnership Potential

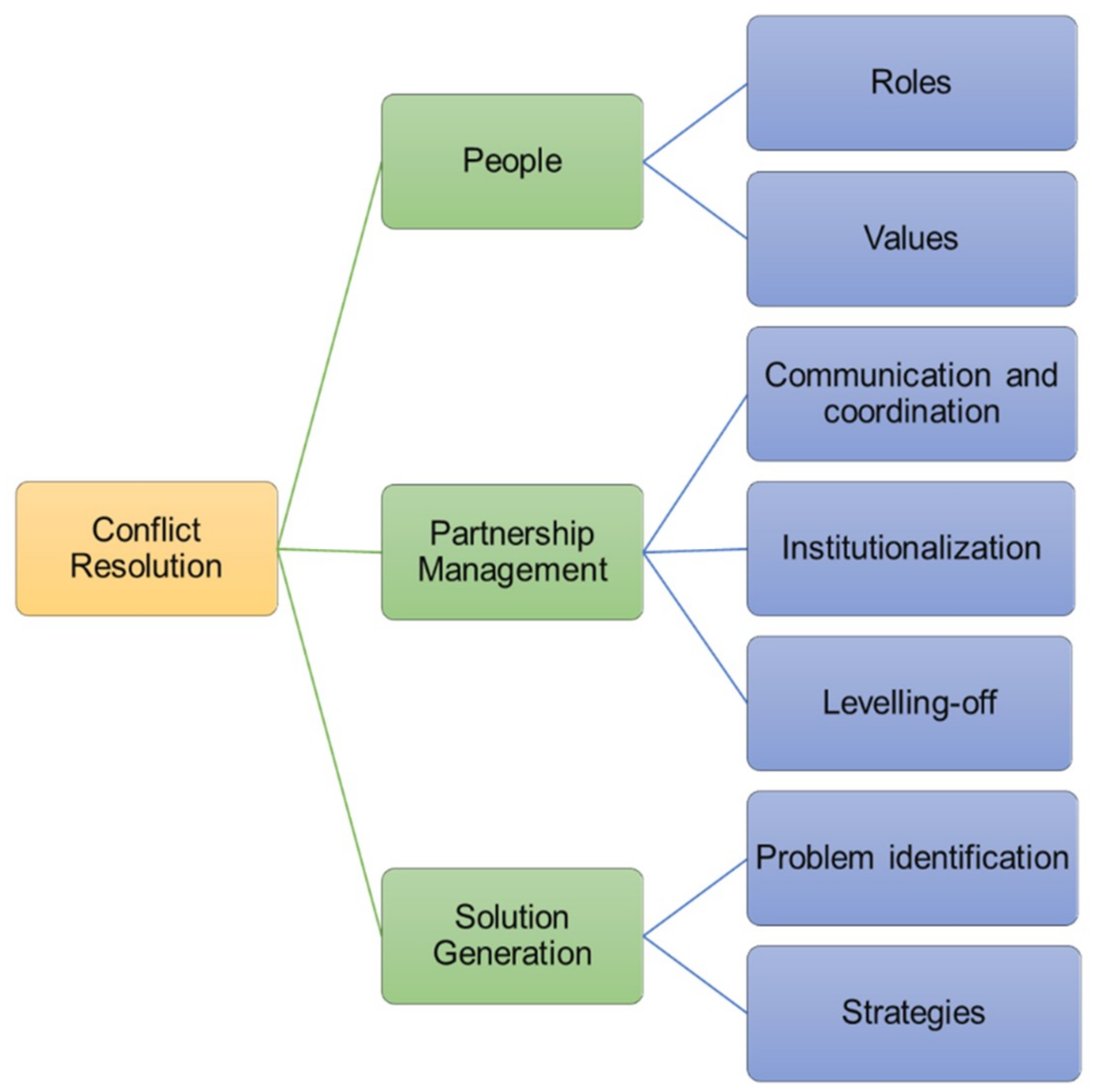

3.2. Sustainability Factors for University-Community Partnerships

4. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bruning, S.; McGrew, S.; Cooper, M. Town–gown relationships: Exploring university–community engagement from the perspective of community members. Public Relat. Rev. 2006, 32, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.; Fabricant, M.; Simmons, L. Understanding contemporary university-community connections: Context, practice, and challenges. J. Community Pract. 2004, 12, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Kotval-K, Z.; Kotval, Z.; Mullin, J. University community partnerships. Humanities 2014, 3, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringle, R.; Hatcher, J. Campus–community partnerships: The terms of engagement. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneri, D.R.; Trencher, G.; Petersen, J. Students as change agents in a town-wide sustainability transformation: The Oberlin Project at Oberlin College. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 16, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, L.; Hellwig, M.; Banks, B. The Chicago response to urban problems: Building university-community collaborations. Am. Behav. Sci. 1999, 42, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howitt, R. Governance in local government-university partnerships: Smart, local and connected. SOAC 2013, 1, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Laninga, T.; Austin, G.; McClure, W. Community-university partnerships in small-town Idaho: Addresing diverse community needs through interdisciplinary outreach and engagement. J. Community Engagem. Scholarsh. 2011, 4, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, K.; Conrad, E. Building statewide community-University partnerships: Working with the Maine Municipal Association. Maine Policy Rev. 2012, 21, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- CHED. In Commision on Higher Education Memorandum Order No. 52; Commission on Higher Education: Quezon City, Philippines, 2016. Available online: https://ched.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CMO-52-s.-2016.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- UPLB-DCERP. Department of Community and Environmental Resource Planning; University of the Philippines Los Banos: Los Banos, Philippines, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weerts, D.J.; Sandmann, L.R. Community engagement and boundary-spanning roles at research universities. J. High. Educ. 2010, 81, 632–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, K.; Lindenfeld, L.; Bell, K.; Leahy, J.; Silka, L. Strengthening knowledge co-production capacity: Examining interest in community-university partnerships. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3744–3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trencher, G.P.; Yarime, M.; Kharrazi, A. Co-creating sustainability: Cross-sector university collaborations for driving sustainable urban transformations. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, M.; Cleveland, S. Building engaged communities—A collaborative leadership approach. Smart Cities 2018, 1, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colding, J.; Barthel, S. The role of University campuses in reconnecting humans to the biosphere. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.; Herts, R.; Devance, R. The Newark Fairmount Promise Neighborhood: A Collaborative University-Community Partnership Model. Metrop. Univ. 2014, 25, 127–153. [Google Scholar]

- Shiel, C.; Leal-Filho, W.; Do Paco, A.; Brandli, L. Evaluating the engagement of universities in capacity building for sustainable development in local communities. Evaluation Program Plan. 2016, 54, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mtawa, N.; Fongwa, S.; Wangenge-Ouma, G. The scholarship of university-community engagement: Interrogating Boyer’s model. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2016, 49, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNall, M.; Reed, C.; Brown, R.; Allen, A. Brokering community–university engagement. Innov. High. Educ. 2009, 33, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, B. Linking theories of service-learning and undergraduate geography education. J. Geogr. 2001, 100, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, C.A. University-community partnerships as a pathway to rural development: Benefits of an Ontario land use planning project. J. Rural Community Dev. 2015, 10, 56–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ruoppila, S.; Zhao, F. The role of universities in developing China’s university towns: The case of Songjiang university town in Shanghai. Cities 2017, 69, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.S.; Baek, T.Y.; Kang, J.M. Review of the Physical Evaluation Factors of the Campustown Project-Focused on Seoul Campustown Project. J. Korean Soc. Civ. Eng. 2018, 38, 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, M.A. A Community Extension Framework for Philippine Higher Education Institutions: A Model Developed from Small-Scale Climate Change Adaptation Projects of Central Mindanao University. World Sci. News 2018, 105, 204–211. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, K.K. Strengthening the Development of Community-University Partnerships in Sustainability Science Research; The University of Maine: Orono, ME, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell, G.; Lawson, C. A public university as city planner and developer: Experience in the “capital of gfood planning”. Plan. Pract. Res. 2006, 21, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RDP. Calabarzon Regional Development Plan 2017–2022; National Economic and Development Authority Region IV-A: Calamba City, Philippines, 2017.

- Leaf, M.; Hou, L. The “third spring” of urban planning in China: The resurrection of professional planning in the post-Mao era. China Inf. 2006, 20, 553–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DILG. Rationalized Planning System in the Philippines; Department of the Interior and Local Government: Quezon City, Philippines, 2008.

- CHED. Higher Education Statistical Data. Available online: https://ched.gov.ph/statistics/ (accessed on 3 March 2019).

- Torregoza, H. SUCs Soon to be Required to Implement Land Use Development, Infrastructure Plan. Manila Bulletin, 25 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D. Developing a framework for understanding university-community partnerships. Cityscape 2000, 5, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, A.; Northmore, S. Auditing and evaluating university–community engagement: Lessons from a UK case study. High. Educ. Q. 2011, 65, 34–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, E. Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate; Princeton University Press: Lawrenceville, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckey, H. The second step in data analysis: Coding qualitative research data. J. Soc. Health Diabetes 2015, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilau, A.; Witt, E.; Lill, I. Practice Framework for the Management of Post-Disaster Housing Reconstruction Programmes. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Campbell, D.; Dalemarre, L.; Fraser-Rahim, H.; Williams, E. A critical review of an authentic and transformative environmental justice and health community—University partnership. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2014, 11, 12817–12834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Focus Area | Research Stream | Relevant Indicators | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Needs assessment and resource mapping | Local and urban planning | Constraints on technical, financial, and human resources. | Fullerton, 2015 |

| Limited technical capability (e.g., writing, mapping, data collection, and analysis). | Dorsey, 2001; Fullerton, 2015 | ||

| Status of local plans. | Fullerton, 2015 | ||

| University resources (facilities, hardware, software, and human resources). | McNall, Brown & Allen, 2009 | ||

| Human capital and physical infrastructure. | Cox, 2000; Hart & Northmore, 2011 | ||

| Access to facilities and knowledge. | Hutchins, 2013; | ||

| Community needs assessment. | Bramwell & Wolfe, 2008 | ||

| Assessment of partnership potential | Local and urban planning | Scope, target, motivation, key actors, and role of universities in the partnership. | Trencher, Yarime, & Kharazzi, 2013 |

| Previous partnership experience. | Weerts and Sandmann, 2010 | ||

| Partnership benefits (timeliness, cost, capability building). | McNall, Brown & Allen, 2009 | ||

| Sustainability science | Partner location (within or outside the host-community). | Hutchins, 2013 | |

| Partnership interest. | Hutchins, 2013 | ||

| Partnership strategy. | Hutchins, 2013 | ||

| Partnership Sustainability | Sustainability science | Partnership sustainability and issues. | Hill, Herts, & Devance, 2014 |

| Partnership success factors. | Mtawa, Fongwa & Wangenge-Ouma, 2015 | ||

| Partnership-hindering factors (structures, values, interests). | Hill, Herts, & Devance, 2014 | ||

| Community engagement | Partnership success factors (goals, expectations, facilities, monitoring, and evaluation). | Weerts & Sandman, 2010 | |

| Conflict resolution and reciprocity. | Weerts & Sandmann, 2010, Cleveland & Cleveland, 2018 |

| Variables | LGU (%) | University (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex of Respondents | Male | 52 | 71 |

| Female | 48 | 29 | |

| Years of Employment | 1 to 10 | 32 | 35 |

| 10 to 20 | 30 | 24 | |

| 21 or more | 38 | 41 | |

| Position or Designation | Mayor/President | 1 | 11 |

| Administrator/Dean or Director | 1 | 53 | |

| Planning Officer | 86 | 12 | |

| Staffs/Faculty or Researcher | 13 | 24 | |

| Institution Classification | City (LGU)/Main Campus (university) | 16 | 76 |

| Municipality (LGU)/Satellite Campus (university) | 84 | 24 |

| Variables (Measurement and Scoring) | LGU | University | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Previous Partnership | ||||

| Checkboxes (without previous partnership = 0; with previous partnership = 1) | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.94 | 0.24 |

| Previous Partnership Helpfulness | ||||

| 11-point Likert scale (strongly disagree = -5; strongly agree = +5) | 2.12 | 3.98 | 3.41 | 1.33 |

| Preferred Partnership Strategy | ||||

| Checkbox (lead = 1; facilitating = 2; consulting = 3; full = 4) | 3.11 | 1.00 | 2.71 | 1.05 |

| Partnership Interest | ||||

| 11-point Likert scale (not interested at all=-5; extremely interested = +5) | 2.77 | 2.05 | 3.59 | 1.50 |

| Preferred Partner Location | ||||

| Checkbox (within LGU =1; within province = 2; within region = 3; outside region = 4) | 2.68 | 1.08 | 2.76 | 1.25 |

| Themes (Assessment) | Variables | Measurement and Scoring |

|---|---|---|

| Local Planning (needs assessment and resource matching) | LGU’s Local Plan Status | Checkboxes |

| (Approved = 1; Ongoing Updating = 2; Updating = 3) | ||

| LGU Planning Assistance | Checkboxes | |

| (Self-prepared = 1; Assistance = 2; Consultants = 3) | ||

| Local Planning Constraints | Checkboxes | |

| (Data Collection and Analysis = 1; Technical Writing = 2; Hazard Mapping = 3; Project Proposal/Development = 4; Layout and Editing = 5; Other = 6) | ||

| Available Planning Resources | Checkboxes | |

| (Funding = 1; Hardware=2; Software=3; Facilities=4; Technical Writers = 5; GIS Mappers = 6; Planning Experts/Specialists = 7) | ||

| Community Engagement (partnership potential) | University-Community Partnership Benefits | Checkboxes |

| [LGU] (Timely Plan Preparation = 1; Less Costly than Hiring Consultants = 2; Access to Experts/Specialists = 3; Capability Building Opportunities for Managers and Staff = 4; Access to Facilities; Hardware and Software = 5; Other = 6) [University] (Career-oriented Exercises and Skill Development for Faculty, Staff, and Students = 1; Positive Community Perception of University Programs, Projects, and Activities = 2; Government Funding and Research Grants = 3; Inclusive Social, Physical and Economic Development Opportunities = 4; High Enrollment in Core Courses such as Agriculture, Engineering, and Other Science-based Courses = 5; Other = 6) | ||

| Partnership Success Factors | Checkboxes | |

| (Common Goals = 1; Clear Expectations and Specific Targets = 2; Stakeholder Buy-in = 3; Availability of Common Planning Facilities = 4; Equal Treatment = 5, Other = 6) | ||

| Partnership-inhibiting Factors | Checkboxes | |

| (Unequal Power = 1; Competing Interests=2; Lack of Coordination and Communication = 3; Different Organizational Values=4; Different Timelines = 5; Loss of Autonomy = 6; Resource Drain = 7; Implementation Challenges = 8; Physical Distance = 9; Ambivalence due to Prior Partnership Experience = 10, Other = 11) | ||

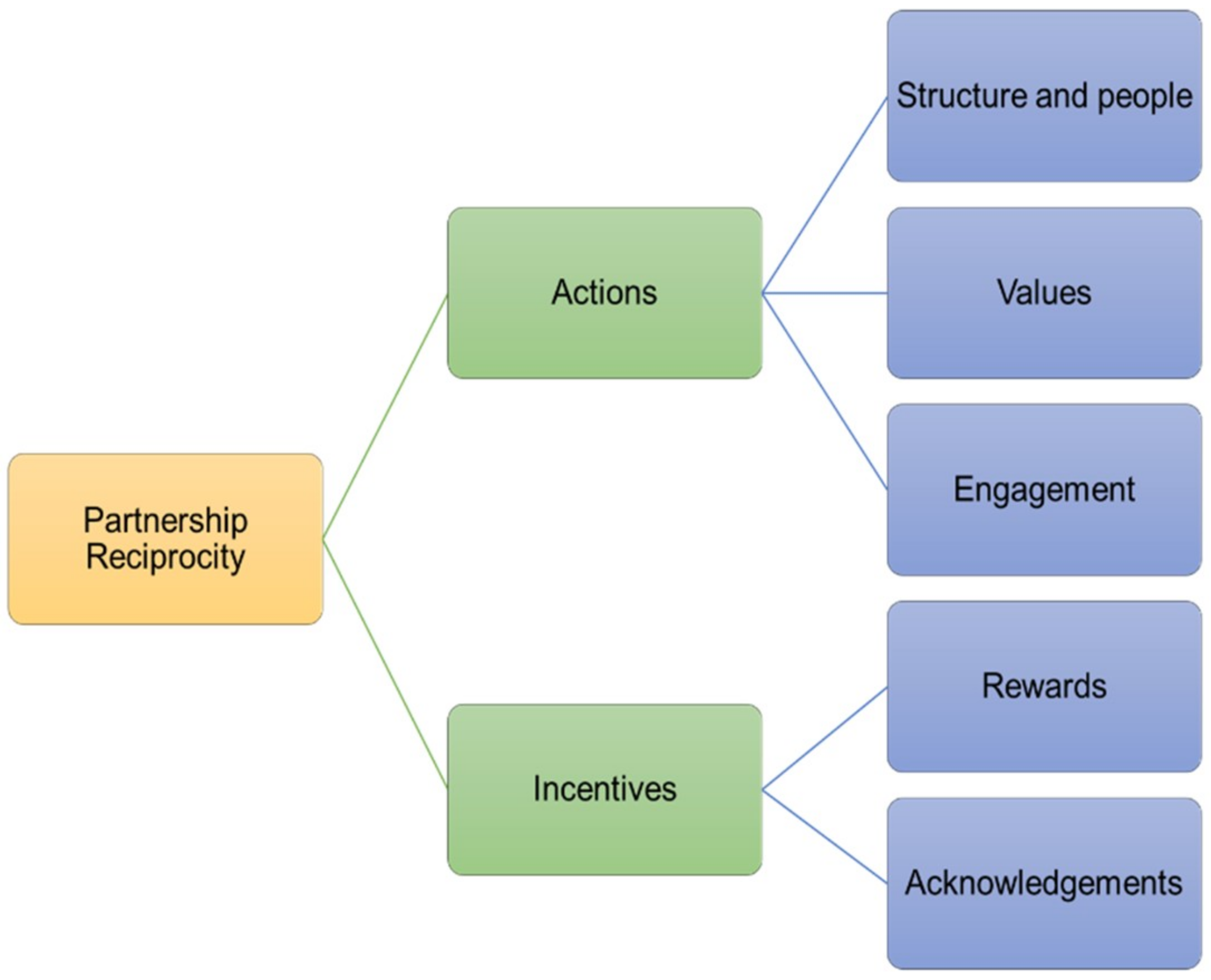

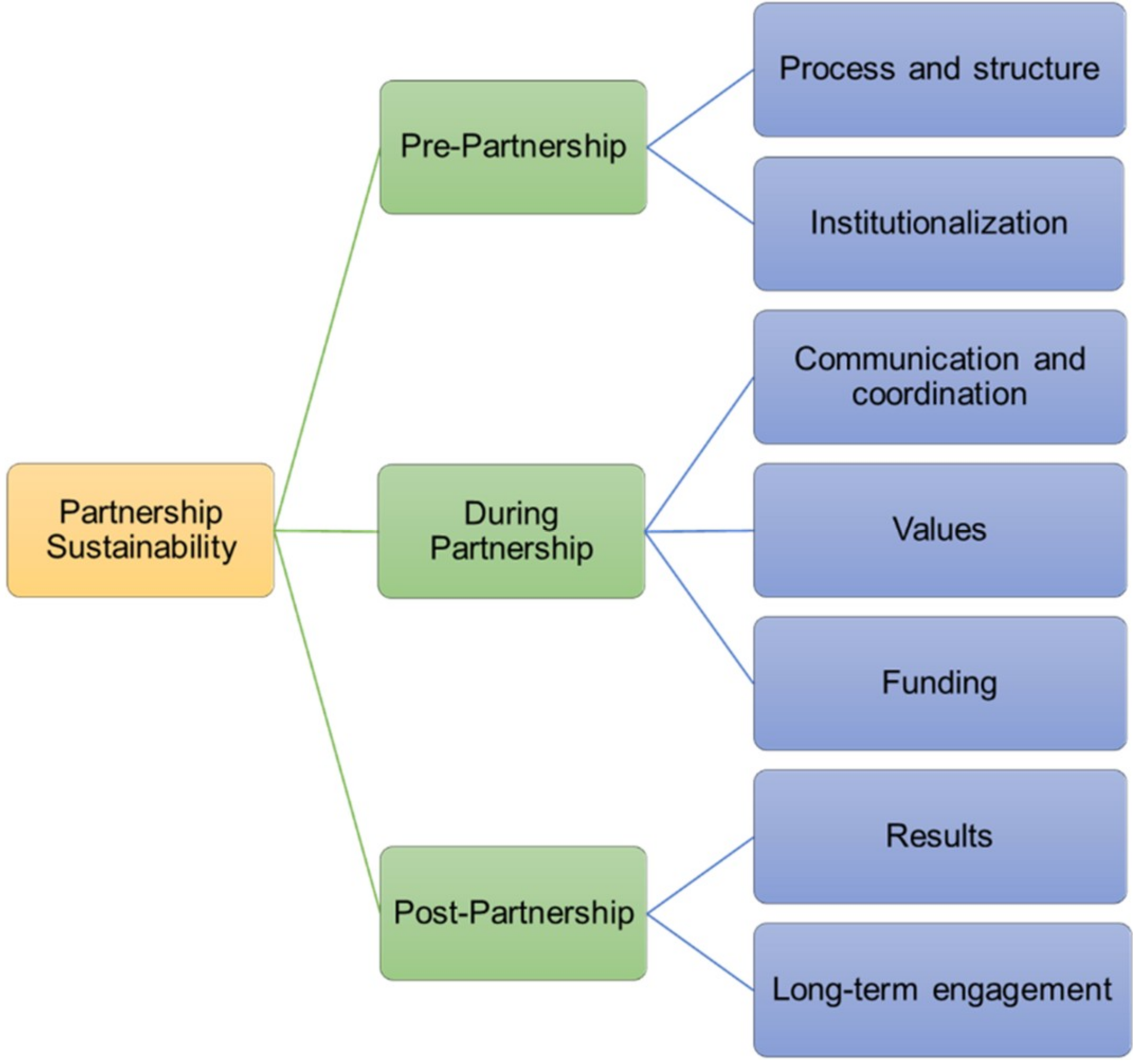

| Partnership Sustainability | Conflict Resolution | Open-ended Questions |

| Partnership Reciprocity | Open-ended Questions | |

| Partnership Sustainability | Open-ended Questions |

| Variable | Previous Partnership Utility | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | Sig. | |

| Sex (male = 0, female = 1) | 0.275 | 0.666 | 0.507 |

| Previous Partnership | 6.552 | 14.945 | 0.000 *** |

| Years of Employment (≤10) | Reference | ||

| Years of Employment (11–20) | −1.005 | −1.936 | 0.055 * |

| Years of Employment (21 or more) | −1.094 | −2.271 | 0.025 ** |

| Organization (LGU) | Reference | ||

| Organization (university) | 1.669 | 2.712 | 0.008 *** |

| R2 =0.73 (Adjusted R2 = 0.72) | |||

| Variable | Partnership Importance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | Sig. | |

| Sex (male = 0, female = 1) | −0.714 | −2.104 | 0.038 ** |

| Previous Partnership | 0.766 | 2.044 | 0.043 ** |

| Years of Employment (≤10) | Reference | ||

| Years of Employment (11-20) | 0.488 | 1.134 | 0.259 |

| Years of Employment (21 or more) | −0.009 | −0.022 | 0.983 |

| Organization (LGU) | Reference | ||

| Organization (university) | 1.281 | 2.533 | 0.013 ** |

| Partnership strategy (full) | Reference | ||

| Partnership strategy (lead) | −1.603 | −2.528 | 0.013 ** |

| Partnership strategy (facilitating) | −1.181 | −2.848 | 0.005 *** |

| Partnership strategy (consulting) | −0.736 | −1.688 | 0.094 * |

| Partner Location (anywhere) | Reference | ||

| Partner Location (within LGU) | −1.003 | −1.931 | 0.056 * |

| Partner Location (within province) | −0.336 | −0.764 | 0.446 |

| Partner Location (within region) | 0.276 | 0.607 | 0.545 |

| R2 = 0.26 (Adjusted R2 = 0.18) | |||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mores, L.S.; Lee, J.; Bae, W. University-Community Partnerships: A Local Planning Co-Production Study on Calabarzon, Philippines. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071850

Mores LS, Lee J, Bae W. University-Community Partnerships: A Local Planning Co-Production Study on Calabarzon, Philippines. Sustainability. 2019; 11(7):1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071850

Chicago/Turabian StyleMores, Lovely S., Jeongwoo Lee, and Woongkyoo Bae. 2019. "University-Community Partnerships: A Local Planning Co-Production Study on Calabarzon, Philippines" Sustainability 11, no. 7: 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071850

APA StyleMores, L. S., Lee, J., & Bae, W. (2019). University-Community Partnerships: A Local Planning Co-Production Study on Calabarzon, Philippines. Sustainability, 11(7), 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071850