A Citizen Survey in the District of Steinfurt, Germany: Insights into the Local Perceptions of the Social and Environmental Activities of Enterprises in Their Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Positioning in the Existing Literature and the Starting Point of Our Research

2.1. Why Focus on the Citizen Perception of Sustainability Activities of Enterprises?

2.2. Social and Environmental Activities

2.3. Level of Information

2.4. The Corporate Citizenship of Enterprises in a Region and Citizen Expectation

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Understanding and Relevance of the Social and Environmental Activities

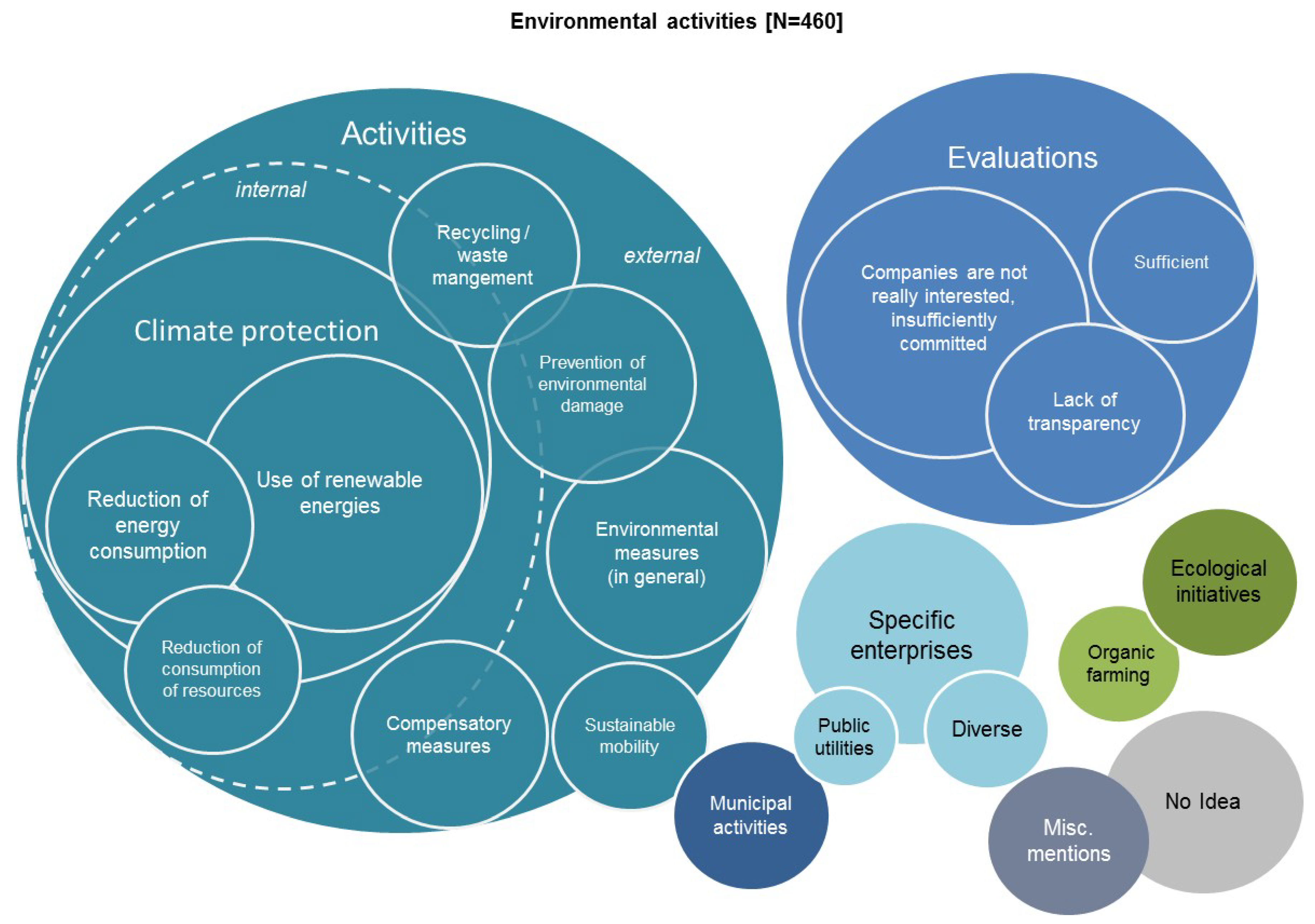

4.1.1. Understanding of the Social and Environmental Activities

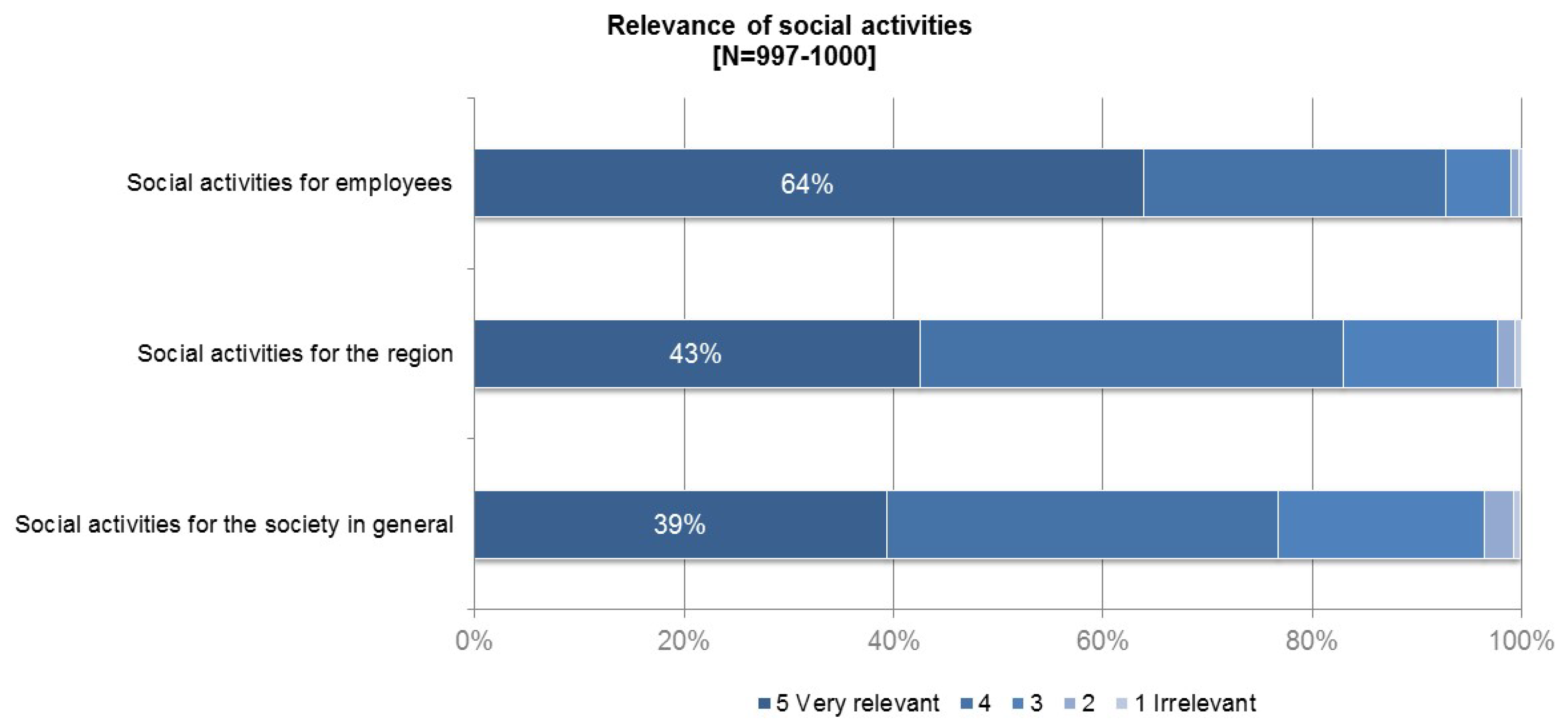

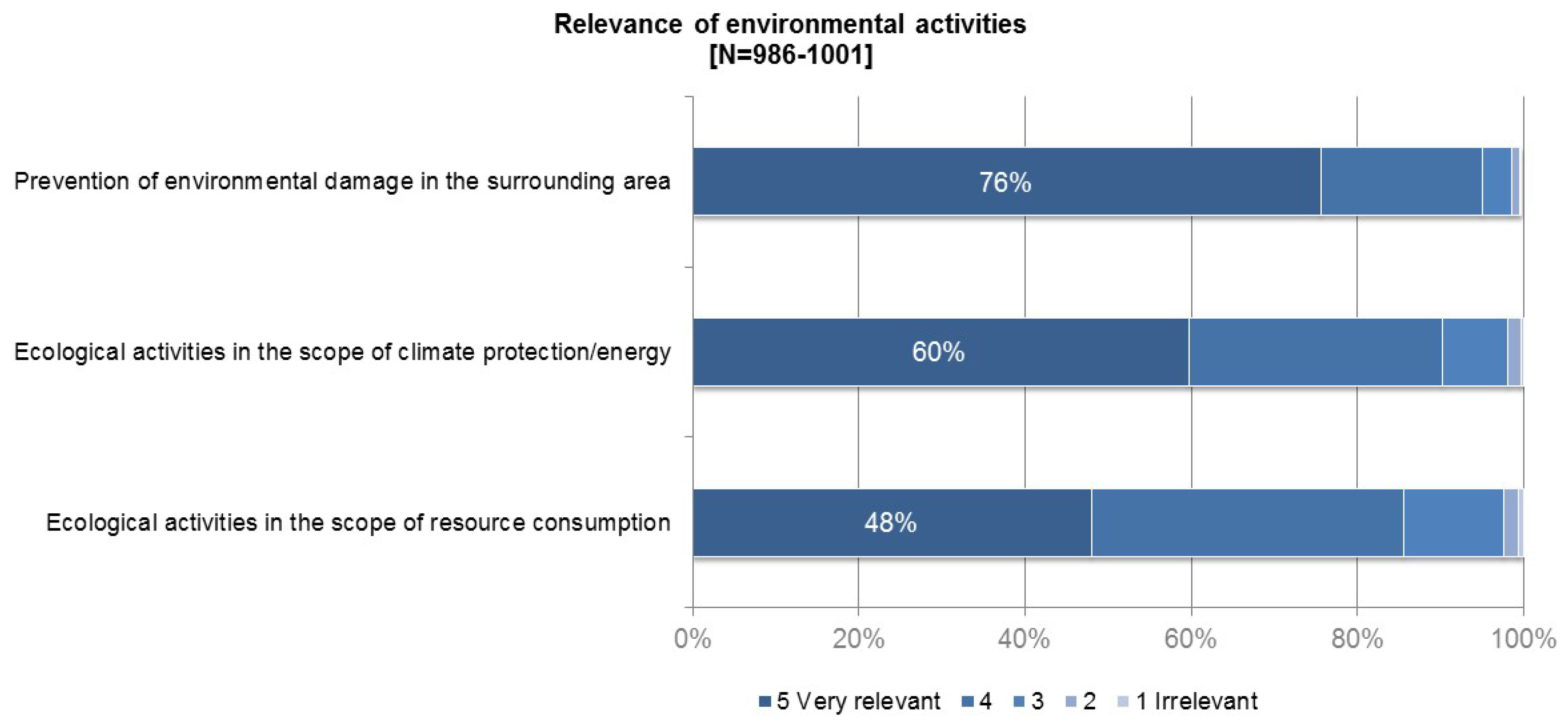

4.1.2. Relevance of Social and Environmental Activities

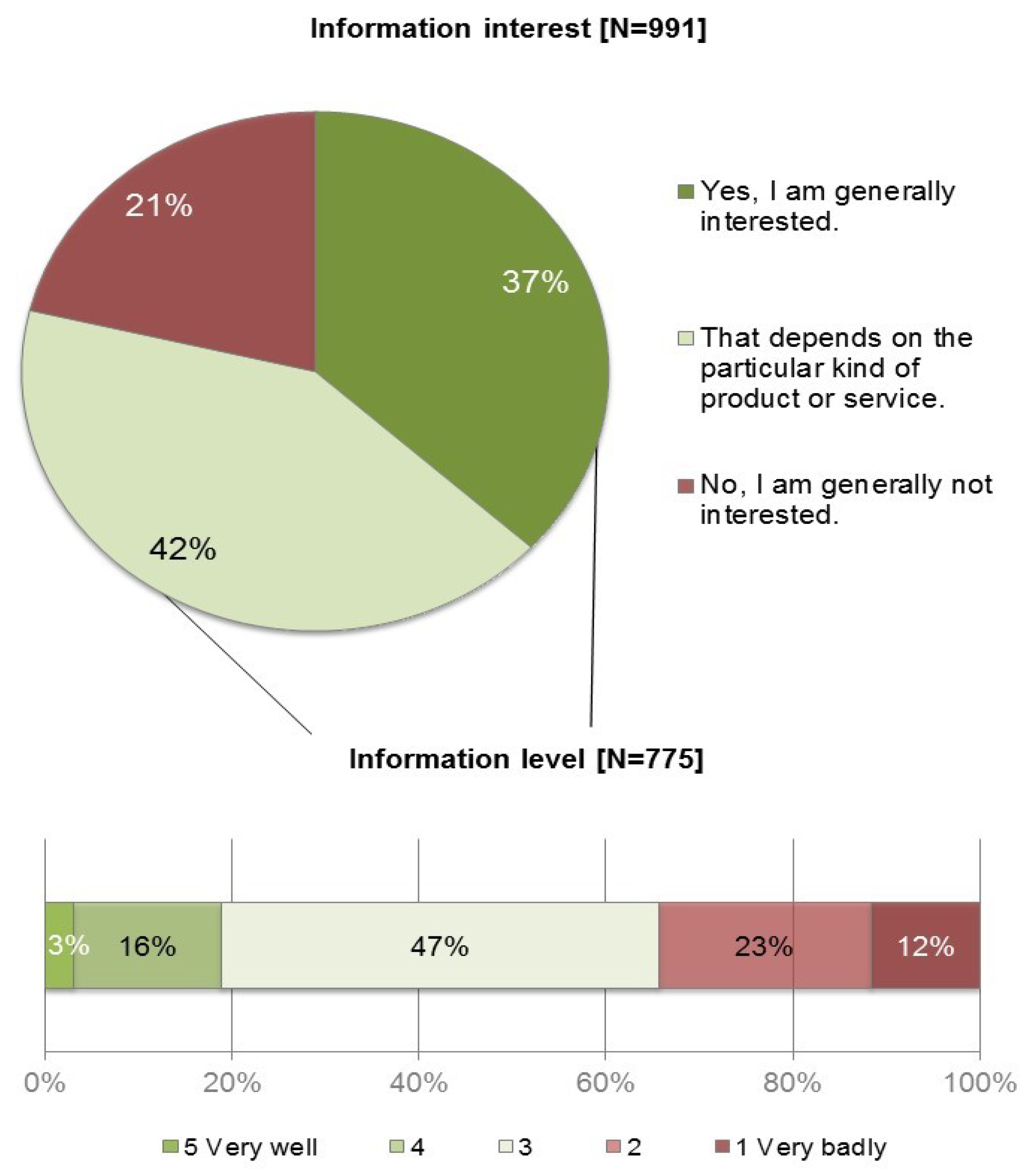

4.2. Information Level and Wish According to Social and Environmental Activities

4.3. Expectations of the Citizens in Terms of Regional Activities by the Enterprises

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WBGU. World in Transition—A Social Contract for Sustainability. German Advisory Council on Global Change, 2001. Available online: http://www.wbgu.de/en/flagship-reports/fr-2011-a-social-contract/ (accessed on 20 December 2017).

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. Business Ethics: A European Perspective: Managing Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability in the Age of Globalization; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppert-Winkel, C.; Kress-Ludwig, M.; Papke, K.; Böhm, M.; Scherf, C.-S.; Funcke, S. Bedeutung sozialer und ökologischer Maßnahmen in KMU für (potenzielle) Mitarbeitende. Eine Fallstudie auf Basis von Befragungen von Mitarbeitenden, zukünftigen Fachkräften und Unternehmensvertreter*innen im Kreis Steinfurt. Umweltpsychologie. Unpublished.

- Hsu, C.H.; Chang, A.Y.; Luo, W. Identifying key performance factors for sustainability development of SMEs—Integrating QFD and fuzzy MADM methods. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Rauter, R. Strategic perspectives of corporate sustainability management to develop a sustainable organization. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Linking stakeholders and corporate reputation towards corporate sustainability. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautermann, C. Verantwortung unternehmen! Die Realisierung kultureller Visionen durch gesellschaftsorientiertes Unternehmertum. Eine konstruktive Kritik der “Social Entrepreneurship”-Debatte; Metropolis: Marburg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van Marrewijk, M. Concepts and Definitions of CSR and Corporate Sustainability: Between Agency and Communion. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D.; Moon, J. The emergence of corporate citizenship: Historical development and alternative perspectives. In Corporate Citizenship in Deutschland: Gesellschaftliches Engagement von Unternehmen. Bilanz und Perspektiven, 2nd ed.; Backhaus-Maul, H., Biedermann, C., Nährlich, S., Polterauer, J., Eds.; VS Verl. für Sozialwiss: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; pp. 64–91. ISBN 978-3-531-91930-0. [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, U. Corporate Citizenship: Die Unternehmung als guter Bürger? Logos: Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lautermann, C.; Pfriem, R. Corporate Social Responsibility in wirtschaftsethischen Perspektiven. In Handbuch CSR; Raupp, J., Jarolimek, S., Schultz, F., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011; pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The Four Faces of Corporate Citizenship. Bus. Soc. Rev. 1998, 100, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randy Evans, W.; Davis, W.D. An Examination of Perceived Corporate Citizenship, Job Applicant Attraction, and CSR Work Role Definition. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 456–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.P.; Tsai, Y.H.; Joe, S.W.; Chiu, C.K. Modeling the Relationship among Perceived Corporate Citizenship, Firms’ Attractiveness, and Career Success Expectation. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, S. Virtue ethics, CSR and “corporate citizenship”. J. Commun. Manag. 2014, 18, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedermann, C. Corporate Citizenship in der Unternehmenskommunikation. In Corporate Citizenship in Deutschland: Gesellschaftliches Engagement von Unternehmen. Bilanz und Perspektiven; Backhaus-Maul, H., Biedermann, C., Nährlich, S., Polterauer, J., Eds.; Aktualisierte und Erweiterte Auflage; VS Verl. für Sozialwiss: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; pp. 353–370. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.M.M.; Fellows, R.; Tuuli, M.M. The role of corporate citizenship values in promoting corporate social performance: Towards a conceptual model and a research agenda. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2011, 29, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, T. Gaining Access by Doing Good: The Effect of Sociopolitical Reputation on Firm Participation in Public Policy Making. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 1989–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabenstott, M. New Policies for a New Rural America. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2001, 24, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arato, M.; Speelman, S.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Corporate Social Responsibility Applied for Rural Development: An Empirical Analysis of Firms from the American Continent. Sustainability 2016, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varian, H.R.; Buchegger, R. Grundzüge der Mikroökonomik. Studienausgabe (7th Ed.). Internationale Standardlehrbücher der Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften, 2007. Available online: http://deposit.d-nb.de/cgi-bin/dokserv?id=2923082&prov=M&dok_var=1&dok_ext=htm (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Kaufmann-Hayoz, R.; Bamberg, S.; Defila, R.; Dehmel, C.; Di Giulio, A.; Jaeger-Erben, M.; Matthies, E.; Sunderer, G.; Zundel, S. Theoretische Perspektiven auf Konsumhandeln—Versuch einer Theorieordnung. In Wesen und Wege nachhaltigen Konsums. Ergebnisse aus dem Themenschwerpunkt “Vom Wissen zum Handeln—Neue Wege zum nachhaltigen Konsum”; Defila, R., Ed.; Oekom: München, Germany, 2012; pp. 89–124. ISBN 978-3-86581-296-4. [Google Scholar]

- Preisendörfer, P.; Diekmann, A. Umweltprobleme. In Handbuch soziale Probleme, 2nd ed.; Albrecht, G., Groenemeyer, A., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 1198–1217. ISBN 9783531321172. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P. Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.P. Modeling Corporate Citizenship, Organizational Trust, and Work Engagement Based on Attachment Theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Tsai, Y.H.; Lin, C.P. Modeling the relationship between perceived corporate citizenship and organizational commitment considering organizational trust as a moderator. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2013, 22, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social Identity Theory and the Organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Greening, D.W. Corporate Social Performance and Organizational Attractiveness to Prospective Employees. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 658–672. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. How Corporate Social Responsibility Influences Organizational Commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, K.; Stone, B.A.; Heiner, K. Exploring the Relationship between Corporate Social Performance and Employer Attractiveness. Bus. Soc. 2002, 41, 292–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does Doing Good Always Lead to Doing Better? Consumer Reactions to Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öberseder, M.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Gruber, V. “Why Don’t Consumers Care About CSR?”: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Role of CSR in Consumption Decisions. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwan, P. Der informierte Verbraucher? Das Verbraucherpolitische Leitbild auf dem Prüfstand; eine Untersuchung am Beispiel des Lebensmittelsektors; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften/GWV Fachverlage GmbH Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-531-16400-7. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, R.; Menichini, T. A multidimensional approach for CSR assessment: The importance of the stakeholder perception. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hur, W.M.; Yeo, J. Corporate Brand Trust as a Mediator in the Relationship between Consumer Perception of CSR, Corporate Hypocrisy, and Corporate Reputation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3683–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Doing Better at Doing Good: When, Why, and How Consumers Respond to Corporate Social Initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 47, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and Society: The Link Between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, V.; Schrader, U. Corporate communication to promote consumers’ social responsibility? A new type of CSR communication. Ökol. Wirtsch. 2011, 2, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, U.; Muster, V. Gesellschaftliche Verantwortung von Unternehmen. Wege zur mehr Glaubwürdigkeit und Sichtbarkeit; Metropolis: Marburg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boulstridge, E.; Carrigan, M. Do consumers really care about corporate responsibility?: Highlighting the attitude—Behaviour gap. J. Commun. Manag. 2000, 4, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Attalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer—Do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Korschun, D. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Strengthening Multiple Stakeholder Relationships: A Field Experiment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomering, A.; Dolnicar, S. Assessing the Prerequisite of Successful CSR Implementation: Are Consumers Aware of CSR Initiatives? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Gao, Y.; Shah, S. CSR and Customer Outcomes. The Mediating Role of Customer Engagement. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.; Thai, V.; Wong, Y. Are customers willing to pay for corporate social responsibility? A study of individual-specific mediators. Total Qual. Mana. Bus. Excell. 2016, 7, 912–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junquera, B.; Barba-Sánchez, V. Environmental Proactivity and Firms’ Performance: Mediation Effect of Competitive Advantages in Spanish Wineries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, I.; Seele, P. Theorizing stakeholders of sustainability in the digital age. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.V.; Wang, X.H. Sustainable Development Governance. Public Work. Manag. Policy 2012, 17, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, S.; Brenninger, K. CSR and its Potential Role in Employer Branding. An Analysis of Preferences of German Graduates. Making the Number of Options Grow. Contributions to the Corporate Responsibility Research Conference 2013; Baumgartner, R.J., Gelbmann, U., Rauter, R., Eds.; ISIS Reports, 6; Universität Graz: Graz, Austria, 2014; Available online: https://static.uni-graz.at/fileadmin/urbi-institute/Systemwissenschaften/ISIS_Reports/ISIS_reports_6_CRRC.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2017).

- Weitzel, T.; Eckhardt, A.; Laumer, S.; Maier, C.; von Stetten, A.; Weinert, C. Bewerbungspraxis 2014. Centre of Human Resources Information Systems, Otto-Friedrich Universität Bamberg, Goethe Universität Frankfurt am Main. Available online: https://www.uni-bamberg.de/fileadmin/uni/fakultaeten/wiai_lehrstuehle/isdl/Bewerbungspraxis_2014.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2017).

- Abel-Koch, J. Weltweit Machen sich Mittelständler für Gesellschaftliche Interessen Stark. KfW Research 159. 2017. Available online: https://www.kfw.de/PDF/Download-Center/Konzernthemen/Research/PDF-Dokumente-Fokus-Volkswirtschaft/Fokus-Nr.-159-Januar-2017-CSR-im-Mittelstand.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2017).

- Castejón, M.; Juan, P.; López, B. Corporate social responsibility in family SMEs: A comparative study. Eur. J. Fam. Bus. 2016, 6, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidhöfer, L. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Kleinen und Mittleren Unternehmen; Grin Verlag Open Publishing GmbH: München, Germany, 2011; ISBN 9783640955534. [Google Scholar]

- Dresewski, F. Verantwortliche Unternehmensführung: Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) im Mittelstand; UPJ e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2007; ISBN 978-3-937765-02-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bluhm, K.; Geicke, A. Gesellschaftliches Engagement im Mittelstand. Altes Phänomen oder neuer Konformismus? In Die Natur der Gesellschaft; Rehberg, K.-S., Ed.; Campus Verlag (Verhandlungen des Deutschen Soziologentages): Frankfurt, Germany, 2008; pp. 5699–5713. ISBN 9783593384405. [Google Scholar]

- Lunau, Y.; Ulrich, P.; Streiff, S. Soziale Unternehmensverantwortung aus Bürgersicht: Eine Anregung zur Diskussion im Auftrag der Philip Morris GmbH; Institut für Wirtschaftsethik: St. Gallen, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Öberseder, M.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Murphy, P.E. CSR practices and consumer perceptions. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1839–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommerening, T. Gesellschaftliche Verantwortung von Unternehmen. Eine Abgrenzung der Konzepte Corporate Social Responsibility und Corporate Citizenship. 2015. Available online: https://www.upj.de/fileadmin/user_upload/MAIN-dateien/Infopool/Forschung/pommerening_thilo.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Russell, D.W.; Russell, C.A. Here or there? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility initiatives: Egocentric tendencies and their moderators. Mark. Lett. 2010, 21, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economist. Just good business: A special report on corporate social responsibility. Economist 2008, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.I.; Ghauri, P.N. Determinants influencing CSR practices in small and medium sized MNE subsidiaries: A stakeholder perspective. J. World Bus. 2015, 50, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, M.; Gogu, E. SMEs’ Public Involvement in the Regional Sustainable Development. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 62, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousiolis, D.T.; Zaridis, A.D.; Karamanis, K.; Rontogianni, A. Corporate Social Responsibility in SMEs and MNEs. The Different Strategic Decision Making. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, J.A.; Lucas, K. Workshop Synthesis: Measuring Attitudes; Quantitative and Qualitative Methods. Transp. Res. Procedia 2015, 11, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunau, Y. Erwartungen der Bürger an Unternehmen. In Handbuch Corporate Citizenship: Corporate Social Responsibility für Manager; Habisch, A., Neureiter, M., Schmidpeter, R., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 477–482. [Google Scholar]

- Aya Pastrana, N.; Sriramesh, K. Corporate Social Responsibility: Perceptions and practices among SMEs in Colombia. Public Relat. Rev. 2014, 40, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, L. Targeted Communication: The Key to Effective Stakeholder Engagement. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 226, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschetti, F.; Gaffier, C.; Moglia, M.; Walke, I.; Price, J. Citizens’ perception of the resilience of Australian cities. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.C.; Xia, N.N.; Wu, C.L.; Zhang, X.L.; Yeh, J.L. Communicating the corporate social responsibility (CSR) of international contractors: Content analysis of CSR reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Shared Value. In Corporate Social Responsibility; Schneider, A., Schmidpeter, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 137–153. [Google Scholar]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Measuring Corporate Citizenship in Two Countries: The Case of the United States and France. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 23, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S. From CSR to Corporate Sustainability. Forum CSR International, 2008. Available online: http://www2.leuphana.de/umanagement/csm/content/nama/downloads/download_publikationen/forumCSRinternational09_Schaltegger.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2018).

| Attribute | Manifestation | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 51% |

| Male | 49% | |

| Age Group | 16–34 | 24% |

| 35–49 | 24% | |

| 50–64 | 28% | |

| 65+ | 25% | |

| Educational Level | No leaving qualification/Basic secondary school leaving qualification (from a Hauptschule) | 25% |

| Secondary school leaving qualification (from a Realschule)/Certificate of aptitude for specialized higher education | 47% | |

| University entrance qualification/A-levels | 28% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kress-Ludwig, M.; Funcke, S.; Böhm, M.; Ruppert-Winkel, C. A Citizen Survey in the District of Steinfurt, Germany: Insights into the Local Perceptions of the Social and Environmental Activities of Enterprises in Their Region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061767

Kress-Ludwig M, Funcke S, Böhm M, Ruppert-Winkel C. A Citizen Survey in the District of Steinfurt, Germany: Insights into the Local Perceptions of the Social and Environmental Activities of Enterprises in Their Region. Sustainability. 2019; 11(6):1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061767

Chicago/Turabian StyleKress-Ludwig, Michael, Simon Funcke, Madeleine Böhm, and Chantal Ruppert-Winkel. 2019. "A Citizen Survey in the District of Steinfurt, Germany: Insights into the Local Perceptions of the Social and Environmental Activities of Enterprises in Their Region" Sustainability 11, no. 6: 1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061767

APA StyleKress-Ludwig, M., Funcke, S., Böhm, M., & Ruppert-Winkel, C. (2019). A Citizen Survey in the District of Steinfurt, Germany: Insights into the Local Perceptions of the Social and Environmental Activities of Enterprises in Their Region. Sustainability, 11(6), 1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061767