Abstract

This article addresses the relationship between Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) and the sustainability of public spending in smart hospitals. Smart (technological) hospitals represent long-termed investments where public and private players interact with banking institutions and eventually patients, to satisfy a core welfare need. Characteristics of smart hospitals are critically examined, together with private actors’ involvement and flexible forms of remuneration. Technology-driven smart hospitals are so complicated that they may require sophisticated PPP. Public players lack innovative skills, whereas private actors seek additional compensation for their non-routine efforts and higher risk. PPP represents a feasible framework, especially if linked to Project Financing (PF) investment patterns. Whereas the social impact of healthcare investments seems evident, their financial coverage raises growing concern in a capital rationing context where shrinking public resources must cope with the growing needs of chronic elder patients. Results-Based Financing (RBF) is a pay-by-result methodology that softens traditional PPP criticalities as availability payment sustainability or risk transfer compensation. Waste of public money can consequently be reduced, and private bankability improved. In this study, we examine why and how advanced Information Technology (IT) solutions implemented in “Smart Hospitals” should produce a positive social impact by increasing at the same time health sustainability and quality of care. Patient-centered smart hospitals realized through PPP schemes, reshape traditional healthcare supply chains with savings and efficiency gains that improve timeliness and execution of care.

1. Introduction

Healthcare investments represent a central social infrastructure with growing sustainability issues, due to the aging population, and public budgetary pressures. Care delivery models are changing fast due to the increasing cost of care, need to improve access to care, growing complexity in treatment, and increasing involvement of patients. Hospitals are consequently investing heavily in ICT capabilities, to become “smart”, achieving better clinical outcomes, resilience in supply chain and enhancement of patient experience. These changes impact both the design, construction, and operation of hospitals, being so consistent with a PPP/PF investment pattern. Public authorities are stressed to find innovative solutions to foster sustainable welfare and increasingly look for Private Partners through PPP schemes [1].

Recent research has demonstrated that many investors seek investments that yield social benefits in addition to financial returns. The emerging practice of “impact investing” embraces this duality by constructing investment portfolios that jointly optimize both types of outcome. As defined by GIIN, “impact investments are investments made in companies, organizations, and funds with the intention to generate social and environmental impact alongside a financial return” [2,3].

Smart hospitals represent the latest frontier of healthcare impact investments. Technological features are becoming so sophisticated that public authorities hardly possess the know-how to conceive, build, and operate them [4]. Synergies with private players are so recommended and are naturally consistent with PPP backed by PF schemes. At the same time, the introduction of HIT can increase organizational performance, including productivity enhancement and cost reductions able to make this model sustainable and profitable for all the stakeholders. HIT can contribute to hospital profitability by reducing paper chart pulling and document transportation, reducing medical errors, and potentially lowering medical liability costs, as well as decreasing back-office expenses [2].

The infrastructural investments may be related to new buildings, the revamping of existing facilities, or the realization of technological investments. Restructuring of old facilities is often economically inconvenient, and the concept of smart hospitals is so typically referred to new investments.

The health real estate assets in some EU countries (e.g., Italy, Romania, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Slovakia, etc.) are very old. In many cases, without building regeneration, it can be challenging to achieve high levels of standards in the provision of health services. In other cases, it is possible to implement technological investments as telehealth, IoT, or new software and servers regardless of the infrastructural conditions. Anyhow, it is essential to assess if new hospitals or technological investments can produce enough (social and economic) savings to be justified.

The paper focuses on the relationship between PPP and the sustainability of public spending in smart hospitals to determine if public and private interactions best fit risky high-tech investment patterns, ensuring social benefits.

The issue of the public-to-private technological risk transfer will be examined, showing that higher private risk needs to be compensated with more significant returns to make the investment bankable and profitable for the private partner. Higher yields are, however, in contradiction with public budget constraints, and they may so derive from technology-driven savings.

Experience shows that unconditional availability payments to private players may easily be transformed into undeserved rents. RBF can be usefully combined with smart hospitals, linking public payments to effective private performance, and so ensure the sustainability of availability payments.

This approach is coherent with “Health System Performance Projects” undertaken by Central Bank and OECD with the aim of [5]:

- -

- improving health facilities performance through RBF;

- -

- enhancing financial accessibility to health services;

- -

- strengthening the institutional capacity of the Ministry of Health.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, smart hospitals are described with a literature review, together with their innovative investment perimeter and patient-centered issues. In Section 3, the research question is represented in further detail. The proposed model is reported in Section 4. Section 5 provides a numerical example to explain when the model is convenient, and so meets the public interest. Section 6 contains a discussion, and Section 7 includes some concluding remarks, the research limits, and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

The definition of smart hospitals is preparatory to an examination of the proposed social impact investment patterns: according to ENISA [4], a smart hospital relies on optimized and automated processes built on an ICT environment of interconnected assets, particularly based on the Internet of things (IoT), to improve existing patient care procedures and introduce new capabilities.

Bullen et al. [6] claim that modern and friendly hospitals, based on smart technologies and intelligent facilities, contribute to creating a better environment for patients.

Being innovative technologies that are expensive and difficult to conceive and manage, PPP agreements are naturally fit to overcome criticalities, and PF is an original package for investment coverage: evidence shows that PPP models are increasingly used for Science, Technology, and Innovation, and then for smart infrastructures [7,8].

“Patient-centered care” is healthcare that is respectful of, and responsive to, the preferences, needs, and values of patients and consumers [9]. Some authors try to draw out elements of patient-centered care that are important markers of successful patient-centered care: they identify six factors [10]:

- -

- engaging the patient as a whole person [11];

- -

- recognizing and responding to emotions;

- -

- fostering a therapeutic alliance;

- -

- promoting an exchange of information;

- -

- sharing decision-making;

- -

- enabling continuity of care, self-management and patient navigation.

This approach considers the patient as the primary stakeholder and identifies the importance of shared governance mechanisms [10].

A patient-centered approach improves care experience and creates public value for services [12]. Unfortunately, reality often greatly differs from the theory.

Universal healthcare is a public good consistent with a PPP framework, but challenging to make sustainable. PPP schemes can be used to finance specific IT investments in existing public (or private) Hospitals or to build Smart Hospitals. Digitization of services and HIT is a powerful driver of patient-centered value co-creation that fosters socio-economic sustainability [13].

To give an example, “last-mile” remote patient monitoring and home nursing in constant connection with “first-mile” healthcare hubs represent a trendy pattern that reshapes healthcare strategies [14]. Home-patients are the core stakeholders of a Patient-Centered Medical Home, a widely-implemented model for improving primary care, emphasizing care coordination, information technology, and process improvements [15].

Smart healthcare investments can be linked to social impact investments on many complementary levels that concern the following:

- -

- sustainability issues of infrastructural healthcare initiatives; health investments and expenses are influenced by public debt increase that backs universal healthcare coverage and can cause, in time of austerity, undesirable cuts to the health sector [16,17,18]; these social impact investments can so cover emerging social needs;

- -

- funding opportunities with PPP and PF schemes; global infrastructure reports suggest that, in the wake of the fiscal crisis, healthcare PPP are a growing area as governments switch attention to social welfare projects [19]; PF schemes have a levered financial structure where debt service is backed by cash-flow based expectations; the financial return for interested investors has to be consistent with a peculiar risk-return pattern;

- -

- new paying and financing mechanisms as RBF, Capitation or Social Impact Bonds have been studied to find viable solutions in a market-based reform of health [2,20,21,22]; financing models have shifted towards value-based care [23];

- -

- robust and innovative tools: SROI methodology has been proposed to systematically account for broader outcomes of interventions and the value for money of such interventions in health; in particular, some authors consider SROI a very relevant and applicable measure, especially as the global focus shifts from “output” to “impact” and from “generous giving” to “accountable giving” [24];

- -

- the long-termed horizon of these infrastructural investments, and the consequent importance of assuring not ephemeral sustainability, even in terms of resilience to exceptional occurrences.

Healthcare PPP investments remain controversial [25,26], and key concepts like the public sector comparator or the value for money are hotly debated [27,28,29]. This concerns the entire PPP process, typically backed by PF, from project and design to construction and management. Technology re-engineers the whole business model, suggesting new governance patterns where public-private risk and return sharing is better focused and monitored.

Esty et al. [30] report that total PF investment grew by a factor of ten times in a decade. During 2014, the amount invested in PF was more significant than the amounts raised through Initial Public Offerings or venture capital funds [31].

The use of PF has a relatively long history for industrial projects (such as mines, pipelines, and oil fields), while the PPP approach was recently extended to infrastructure projects such as hospitals, toll roads, power plants, telecommunication systems, schools, and prisons [32].

PF involves the creation of a legally independent project company (SPV) financed with limited-recourse debt and with equity from one or more corporate entities (sponsors) financing an industrial or infrastructural project [33]. The project, its assets, its contracts, and its cash flows are segregated from those of the sponsors to obtain the credit appraisal and the loan for the project, independent from the sponsors [34].

PPP implementing large projects under a PF arrangement exhibit the following features [35]:

- -

- projects operate under a concession obtained from the Government;

- -

- the sponsors provide a large portion of the equity for the project company and expertise in developing and running the project;

- -

- the Government may provide equity and running capital for the project company, facilitation for authorizations, and fiscal agreements;

- -

- the sponsors and Government may enter into contracts regarding the long-run ownership and operation of the project.

PF creates value and thus cuts funding costs by resolving agency problems, reducing asymmetric information costs, and improving risk management [35,36,37,38,39], but there are some main problems related to the use of PF, such as complexity in terms of designing the transaction and writing the required documentation, higher costs of borrowing when compared to conventional financing, and negotiation of the financing and operating agreements, which is time-consuming [34,37,38]. Nevertheless, when comparing PF to corporate financing, the additional costs are more than compensated for by the advantages that arise from the reduction in net financing costs associated with large capital investments, off-balance sheet financing, and appropriate risk allocation [38].

PPP are based on competitive auctions where private participants have a natural incentive in proposing technological advancements. They can then be rewarded with higher marks in the tender and expected savings in the management phase [27].

This study is original and—to the authors’ best knowledge—the research question illustrated in Section 3 has never been adequately covered by the extant literature.

3. Research Question and Methodology

This study, starting from the literature debate on the interaction between healthcare sustainability and PPP, concerns the strategic elements to improve smart healthcare investments, making them sustainable, and ensuring a positive social impact.

The research question can be articulated as follows:

- -

- Problem: healthcare needs and costs are growing in Western countries with the ageing population and stronger public budget constraints; the public stakeholders typically lack enough knowledge to autonomously procure and manage technological (smart) solutions.

- -

- Target: technology improves the quality of cares and may create monetary value through savings (optimizing scarce resources); well-being can also be improved, enhancing the socio-economic sustainability of the healthcare system.

- -

- Solution: public players should cooperate with skilled private providers signing PPP agreements; being technology riskier than standard solutions the private actors must be compensated with higher returns; higher public-to-private rewards are however impeded by the budget constraints; additional resources may so be justified only with RBF/pay for performance patterns, where savings are first co-created and then shared; this may ensure much wanted long-term sustainability and support the bankability of the investments.

The research question follows a “process innovation” methodology, according to which several concepts, already discussed in the literature, are sequentially combined in an original way. This is the case considering that healthcare PPP or the use of RBF in healthcare is not a novelty, per se. What is pioneering is their joint combination in a technology-driven scenario where budget constraints threaten long-term socio-economic sustainability. The methodology is better described in paragraph 4, where a PPP model is illustrated and then supported in paragraph 5 by a pilot case of telehealth applications.

Applications of this model to smart healthcare investments improve the understanding of trendy PPP patterns that contribute to sustainable public health.

We assume that the proposed model can make smart healthcare investments more sustainable:

- -

- replacing public spending with private finance;

- -

- postponing public expenditure to the management phase through the availability and service fees payment;

- -

- with savings from traditional care systems and lower hospitalization able to make the availability and service fees sustainable.

4. The model: PPP Combination of Public Interest with Private Technology

The combination of public and private interests seems to be easier with smart investment PPP.

The smart hospital characteristics reshape the PF perimeter and its operations during the management phase. The investment perimeter represents the balance sheet structure of the private SPV that depends on the features and the physical/intangible assets of the healthcare facility. Through its innovative BOT investment pattern, the SPV re-engineers its investment perimeter. Smart assets embedded in the new investment perimeter are incremental and need to be interactively combined with basic facilities since the beginning.

Smart assets reshape operations that follow the construction phase in the PF timesheet. Private constructors have a governance incentive to properly build the hospital, as they then must run it for many years.

Smart functionalities incorporated in infrastructural assets concern the e-devices, which include ICT ecosystem for healthcare services to home-patients:

- -

- medical equipment for tele-monitoring and tele-diagnosis in the form of wearable or implantable devices, etc.;

- -

- medical equipment for distribution of drugs (automated dosing equipment, e.g., for insulin) or to administer treatment;

- -

- telehealth equipment such as cameras, sensors, and telephone/internet connections; a telehealth computer system for patients to self-record core health parameters (e.g., blood pressure).

Biometric or IoT-driven identification systems are used to track and authenticate patients, staff or hospital equipment such as beds, blood bags, or other medical items. In smart hospitals, the scanners are networked with devices and information systems, reducing human error and improving security.

Networking equipment provides the connectivity backbone to support smart hospitals, and mobile client devices are intelligently integrated into smart hospitals to make the right information available wherever and whenever needed. This process facilitates the mobility of staff and patients as in the case of mobile client applications for smartphones and tablets.

Buildings and facilities manage various functions; for example, as power and climate regulation systems through temperature sensors.

Interconnected clinical information systems are deployed jointly with medical devices and identification components to enable smart end-to-end patient care processes. Moreover, clinical networked information systems are increasingly able to make decisions autonomously. Examples include:

- -

- HIS;

- -

- LIS;

- -

- radiology, pharmacy, and pathology information systems;

- -

- blood bank system;

- -

- PACS;

- -

- research information system.

Data become an asset for decisions, supporting all the organizational processes as the following:

- -

- clinical and administrative patient data (e.g., health records, tests results, contact details);

- -

- financial, organizational, and other hospital data;

- -

- research data (e.g., clinical trial reports) and data intended for secondary use; staff data.

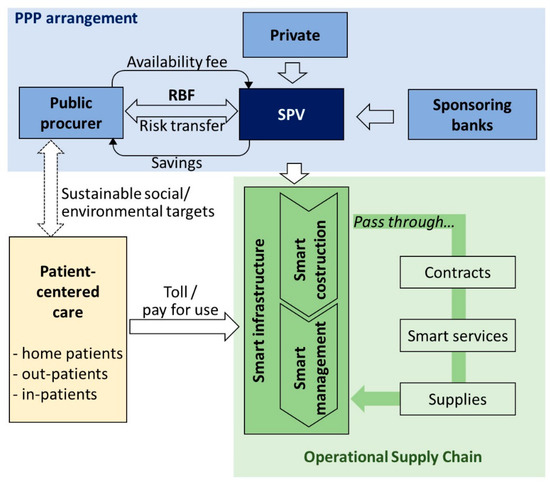

Technology interacts with operational efficiency and patient-centered care, synergistically enhancing the three pillars of sustainability (economic, social, and environmental). Figure 1 synthesizes these interactions.

Figure 1.

Smart hospitals: interaction among the PPP stakeholders along the PF supply chain.

A map of the smart functionalities, operated by the private concessionaire, is necessary for new governance mechanisms that provide optimal allocation of risks between the various stakeholders. Moreover, it is useful to start rethinking services on the base of RBF, as it will be shown in Section 4.2.

PPP represents a suitable combination of the public interest in healthcare with the technological expertise of private suppliers, under the condition described in the model. Figure 1 shows the interaction of the primary stakeholders (patients; public actor; private players and their SPV; banks; etc.) considering the sustainability of the availability fees in the PPP and the value for patients created through the smart supply chain.

The first part of the model describes as follows the relationship between the public procurer, the private SPV, and the sponsoring banks:

- -

- the public procurer pays availability fees during the management phase;

- -

- the public procurer benefits from better risk transfer through RBF;

- -

- the sponsoring banks provide financial resources to the SPV that increases its risk/return profile.

The model describes as follows the relationship between the public procurer, the SPV, and the patients, within the whole supply chain:

- -

- the private SPV implements a new operational supply chain on the base of an agreed service contract;

- -

- the new services are paid through a “pay-per-use” mechanism consistent with RBF; the costs can either be charged to the national healthcare system or to the patients;

- -

- the SPV interacts with other technological suppliers.

In this context, represented in Figure 1, the public procurer ensures social and environmental sustainability, while the private partner provides economic and financial viability.

4.1. Technology and Public-to-Private Risk Transfer

Technological PPP concern additional risk that must be shared between the public and private players.

Risk transfer is a crucial characteristic of PPP, especially if Eurostat rules apply. For public entities, the accounting framework was initially based primarily on a risk and reward criterion described in the Eurostat Decision 2004, and then fully regulated by the implementation of ESA 2010 [40].

The Manual on Government Deficit and Debt (2016) and Eurostat decisions tries to solve the critical question of whether a PPP should be accounted “on balance” and when it can be considered “off balance” for the grantor. The “risks and rewards” criterion drives the decision of how to classify the infrastructure in the public accounts.

The assets should be considered non-governmental (off balance) when the private partner bears the construction risk, and at least one of either the availability or the demand risk. The issue is fierily debated, and insufficient public-to-private risk transfer is often questioned. Interpretation of Eurostat rules is being more mindful in order to prevent abuses and overspending.

Traditional healthcare PF was criticized for its inability to correctly transfer risk, often producing an on-balance accounting treatment of hospital infrastructure [25].

For the public procurer, on-balance investments increase the public debt and are so hardly viable. This is the case especially when the public grants for constructions exceed 50% of the expenditures, or when contract penalties are judged by Eurostat to be insufficient to fully transfer the availability risk.

On the contrary, construction risk is substantially transferred to the private partner when the latter has capital at risk during the construction phase and when availability risk is transferred through the provision of severe penalties in case of underperformance.

Moreover, PPP was judged, in some cases, to be a disaster due to substantial public costs and a government still bearing most of the risk involved in the project [26].

We wonder how smart PF can ensure a better risk transfer while providing at the same time an elevated level of innovation. This study considers the controversy in an innovative way, introducing technological risk in the project, construction, and management phase. This impacts the availability payment that may not be deserved in the presence of poor private performance; hence, the innovation of linking it to RBF. Demand risk can also be influenced by real-time feedback that fuels big data [41] and may be incorporated in artificial intelligence patterns.

To stimulate innovation, each party assuming project risk should share the benefits that arise from innovation. Barlow [42] argues that under traditional PF it was difficult to achieve agreement on the introduction of innovative ideas because of a separation of responsibilities between the project consortium and clinical operations. Whereas the primary goal was a facility delivering excellent healthcare to its patients, for the private sector partners a hospital project was mainly seen as an investment vehicle.

This mismatch in incentives resulted in more cautious attitudes towards risk, mainly when associated with innovative solutions. Barlow [42] found an unwillingness of the private partner to assume any additional risk associated with innovation.

Chirkunova et al. [43] consider PF a suitable instrument for financing innovation.

In smart healthcare, innovation is at the base of the PPP, being contractually stated from the beginning of the awarding procedure. Smart PF schemes must be designed to minimize contractual uncertainties, envisaging a clear risk transfer.

In this context, it is necessary to outline new governance mechanisms in which the role and responsibility of each subject are contractually identified, remembering that the private partner bears an additional operational risk.

In smart investments, the private player takes construction risk (where technology is embedded since inception) and demand risk for “hot” (commercial activities), which include smart applications. Availability risk needs to be interpreted innovatively, adapting to the real functionality of smart infrastructure during the operational phase.

Table 1 compares traditional PF with smart investments.

Table 1.

Public and private risk-sharing in traditional and smart PF.

Table 1 shows how smart hospital PF allows a more intensive risk transfer (compared to traditional PF) particularly in availability risk, with the possibility to provide additional rewards for the greater risk exposure of private actors.

In traditional PF, the design is sourced from public feasibility studies that shape the tender, limiting public-private confrontation, and opportunities for innovation are limited. In smart hospitals, private involvement is anticipated in the design of the infrastructure, and innovation becomes a vital task of the private partner.

Moreover, because in smart hospitals higher risks are transferred, it is easier to demonstrate that the majority of risks are covered by the private partner, in compliance with Eurostat rules. Contractual agreements and penalties strictly linked to results (and consistent with the RBF approach that will be examined in Section 4.2.) will consequently allow an off-balance accounting of the assets.

The annual availability fee, recognized by the grantor to the private operator of the smart hospital, will consequently represent a current expense for the public administration recognized on the base of measurable performance, even on an RBF basis.

When caring for a patient through Smart Technologies, specialized knowledge and responsibility are needed, and this compels the industry into a networked mode of operation, with risk sharing needs.

Adequate risk transfer from traditional to smart PPP investments needs to be properly executed since inception to avoid failures.

A preliminary conclusion may be drawn: healthcare PPP/PF criticalities also concern insufficient public-to-private risk transfer. Technological risk exacerbates the problem, and its transfer to the private stakeholders needs to be compensated with higher returns also to reward the private partners and their sponsoring banks properly.

4.2. Technological Risk and Returns: Making the Availability Payment Sustainable with RBF

As anticipated in Section 4.1., risk transfer is a critical issue in PF and raises the following trade-off:

- -

- from the public side, there is a necessity to transfer a higher risk component to the private player, because of a stricter interpretation of Eurostat rules but also considering that innovative investments are riskier than standard ones;

- -

- from the private side, a higher risk may decrease profitability and raise bankability concerns.

In PF, the availability payment remunerates the SPV (evidenced in Figure 1) with “cold” revenues that do not depend on market risk like “hot” commercial revenues.

In traditional healthcare PF, availability payments to the private actor depend on the possibility for the public player to use a well-functioning hospital. Contractual provisions link the availability payments to the meeting of binding quality standards. If they are not (entirely) met, the fee is either decreased or stopped.

Healthcare providers operate in a pay-for-service model, with an incentive to provide more services than necessary. As treatments are getting better by applying innovative technologies, these incentives could be removed by changing to a pay-by-success model. RBF goes in the direction of “paying for performance”, ensuring more patient-centered management, and it is consistent with Value-Based healthcare delivery [44].

How to achieve an improved outcome at lower costs is a challenging area of study. Some relevant authors conclude that “we need to change the nature of competition, so it would reward those who deliver the highest value for the patient”. Value is defined as a “better outcome achieved at lower costs”, and some authors propose to accelerate the outcome measurement in health by applying time driven activity-based costing along the care cycle [45].

In this context, the burden of the affordability of the availability payment emerges as a critical long-term consequence of PF schemes where private remuneration (also considering the public grants and the revenues from “hot” commercial operations) may become hardly sustainable.

For example, UK hospital trust annual payments to the private partner were higher than expected. Shaoul et al. [25] estimated an additional cost of PF finance, for 12 hospitals in the UK, of about 60 M £ for a year, corresponding to 20–25% of the trust income. They found it extremely difficult for hospitals to penalize deficient performance and effectively transfer risk. Moreover, because the demand risk was not fully transferred, and the private partner was mainly treated as a finance debtor, a minor risk was passed from the trust to the private. These criticalities led to a wave of mistrust in PF, and in BOT procedures.

The idea of remunerating smart hospital services with availability payments on the basis of management results also bears unknown criticalities. Traditional criticism over availability payment affordability is however reduced by reported significant savings by the adoption of ICT technologies [46].

Risk can, however, be softened, up to an ideal complete elimination, making it flexible, i.e., linked to performance and results. This strategy reduces private rents (free riding) but also allows for higher compensation, whenever it is deserved.

This goal is neither easy nor immediate, and satisfactory results depend upon a well-structured healthcare supply chain. This is complemented by flexible agreement between the involved parties ensuring the optimal allocation of risks and fair compensation of private investments linked to concrete results.

Smart PF sustainability can be partly based on availability payments in which risks are ultimately operational, intrinsically manageable, and dependent on the performance and management of the private partner. Operational performance can be monitored with a comparison with standard costs for the same task, within a transaction cost framework.

As an example, a private operator in charge of the implementation of telemedicine systems and distance monitoring of patients could be remunerated on the basis of the number of patients treated with the new system, with a “shadow toll” mechanism (public to private payment without the involvement of the patients).

Smart healthcare can perform many tasks in a better way, generating public savings that can be partially assigned to private remuneration.

Managing by objectives is a strategy consistent with RBF that requires:

- -

- defining the appropriate number of indicators that work as objectives;

- -

- choosing the correct principle to determine which indicators should be considered as high priorities.

Savedoff [47] focuses on the range of RBF approaches, more extensive and diverse than ever before. In short, a relevant decision in RBF is based on input (pay for services), output (pay for useful results) or outcomes (pay for useful results).

This approach must be associated with payments mechanisms as:

- -

- fee-for-service: Providers are paid a fee for each service that they render to a patient;

- -

- case-based payments: Providers are paid a fee for each treated case, independently of the type or intensity of services that are required and rendered;

- -

- capitation: Providers are paid a fixed amount for each person enrolled in their care and are expected to provide all the services needed by that individual during the term of enrollment.

Some of these approaches best fit with smart hospitals PPP. Typical measurable indicators are the number of reservations via mobile, number of electronic payments, number of dematerialized processes, savings in prints and paper, level of productivity for an employee, and maintenance costs.

Fees for service payments can be provided and incentives recognized when specific performance targets are achieved as a certain percentage (on the total) of reservations are made through IT systems or the number of defaults of the equipment is reduced.

Health systems and patient management present higher criticality for the need for coordination between technological performance and medical activities. In this field of operations, RBF should be based on specified outcomes verified for quality and only occasionally on outputs.

Typical measurable indicators are the number of medical records available online, number of doctors and staff that access systematically electronic records, number of patients using implantable devices, and the number of patients using a remote care system, etc.

For some of these activities “Case-Based Payments” or “Capitation” can be appropriate, and incentives should be recognized when specific quality targets are achieved, or high patient satisfaction is reported. In this case, incentives should include both technical and medical staff, extending the rewarded stakeholders beyond private investors or patients.

Successful RBF programs must introduce a material incentive but also help to:

- -

- align objectives between the grantor and IT providers;

- -

- collecting reliable information on results;

- -

- give both private operators and medical staff a stake in the outcome of their efforts, and higher discretion to carry out their tasks.

RBF has the potential to be usefully employed in smart PF investments, softening the sustainability issues of availability payments and transferring operational risk from the public to the private part, in compliance with Eurostat rules.

RBF can help to strengthen healthcare systems, making them more accountable and delivering higher value for money by shifting the focus from inputs to results. As a contracting approach, RBF can contribute to reinforcing PPP, aligning private providers with national health policies to attain public health goals. These general statements can be applied even to the peculiar case of smart hospitals, where innovative technicalities need to be harmonized with resilient supply chains.

RBF introduces checks and balances along the delivery chain, encouraging better governance, transparency, and enhanced accountability.

Linking availability payments to RBF can soften affordability issues, transferring a higher risk to the private side, in compliance with Eurostat rules.

Since RBF can produce higher returns, there is a possible remuneration of the private extra-risk.

The following statement synthesizes these findings: higher private remuneration for the extra-risk transferred is in contrast with public budget constraints. A solution can be given by the technology-driven extra-savings that can fuel RBF equity, to be shared between the public and the private stakeholders.

5. An Example of Telehealth Application to Chronic Diseases

In Italy, about 7.5 million patients are suffering from chronic diseases that could be managed with remote monitoring with significant budget savings [48,49]. According to the projections of the ICT Health Observatory of the Milan Polytechnic, savings of at least 6.8 billion Euros for a year could be achieved through extensive use of digital healthcare in the critical areas of the National Health Service. Savings are made possible by technology and may be partially used to finance PPP smart investments, fueling a virtuous cycle [50].

Telehealth is focusing on older adults with non-communicable diseases like CHF, diabetes, COPD, etc. Complications from these chronic diseases can be consistently reduced with the assistance of daily monitoring. Telehealth reduces hospitalization of chronic patients [51].

We use data from a public Hospital in Abruzzo (central Italy), the “S.S. Annunziata of Chieti”, to provide a preliminary estimation of mid-term public spending savings.

Official data of the ASL 2 Lanciano—Chieti show the Policlinico SS Annunziata (a big and old hospital) provided, in 2016, 133,996 days of hospitalization (5.5 days for patient on average) to 20,709 patients of which 81.2% for acute care and 18.8% for non-acute care [52].

In our estimation we consider:

- -

- only the non-acute hospitalization (18.8%) potentially linked to chronical diseases;

- -

- we estimate only 23.7% of the previous hospitalization due to chronical disease in line with the reported percentage in 2015 of Italian population suffering Chronical disease [52];

- -

- consequently, we estimate a total of 5079 hospitalization days due to chronic disease in Policlinico S.S. Annunziata (about 4.5% of hospitalizations).

Which is the potential reduction of Hospitalization due to Telehealth?

Research from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services shows a reduction in hospitalization as well as costs savings based on priority diagnoses. This study has quantified a significant impact on key performance indicators and costs for 167 patients in the telehealth program in 2012, reducing hospitalization and visits to an average of 65% for target diagnoses resulting in an estimated $ 2.1 million in health care savings (Table 2) [53].

Table 2.

Reduced hospitalization in EMHC (U.S.).

In line with the Italian National Plan for chronical diseases, we assume a prudential reduction of hospitalization of about 30% for telehealth applications. A reduction of hospitalization of 1524 days over 113,998 represents a little decrease of 1.23% (Table 3). This estimate is highly watchful, and implies that about 277 patients for year avoid hospitalization of (on average) 5.5 days.

Table 3.

Potential reduced hospitalization in Policlinico S.S. Annunziata of Chieti.

Which is the expected saving for the hospital budget?

In Italy, the total cost of hospitalization for a patient for a day has been estimated on average at the national level ranging from 400 to 800 euros [54]. In S.S. Annunziata of Chieti, the cost of hospitalization is about euro 4000 for an average stay of 5.5 days that implies a daily cost of about 727 euros.

A remote patient system (tele-medicine) can have a monthly cost between 80 and 120 euros that mean a daily cost of the IT facility of about 3.3 euro. It is so possible to quantify expected savings of 724 euros for the patient/day. According to the data, public cost savings can be estimated at about 1.1 million euros for a year (Table 4).

Table 4.

Value creation (savings) for a year—Policlinico S.S. Annunziata of Chieti.

This estimation is limited to public budget savings and does not include the social and economic savings for patients who benefit from reduced mobility costs, home assistance, higher quality of care thanks to continuous monitoring, etc.

The estimated public savings can cover the cost of the availability fee of a hypothetical PPP contract. This is an essential precondition of any price sector comparator or value for money consideration, preliminary to the choice to undertake a PPP/PF investment compliant with Eurostat rules. To give an example, over 15 years’ contracts, these savings allow:

- -

- the coverage of a technological investment of about 9 million euros through private resources without any preliminary public spending;

- -

- an internal rate of return of about 8.8% for the private partner, showing its level of profitability; this return is currently higher than the cost of collected capital, so bringing to a positive Net Present Value of the investment;

- -

- a public-to-private transfer of technological and managerial risks;

- -

- a repayment linked to the expected savings through RBF mechanisms.

This example just represents a pilot case. Further empirical evidence to assess the savings of telehealth applications is needed, whenever available on a larger scale.

6. Discussion

Healthcare systems throughout the world undergo significant changes driven by aging populations, budget constraints, and advances in biomedical technologies [10,55].

With this trade-off between tightening budgets and skyrocketing costs, many countries are seeking to identify ways of using ICT and introducing new procurement models.

Economic and financial sustainability of smart hospitals, backed by PF, represent a pre-requisite for the realization of long-lasting social impact investments. Many complementary factors need to properly interact to guarantee the sustainability of the private SPV:

- -

- the price of the investment, in the form of the public grant contribution for the building and, sometimes, the biomedical equipment;

- -

- the availability payment, represented by the annual rent paid to the private concessionaire; due to the Eurostat risk transfer rules, part of the availability payment (up to 50% or more) is conditionally subordinated to effective management and working of the hospital and is so subject to fines if the service provided is inadequate;

- -

- the economic margin of the no-core services, within the investment perimeter, with a proper blending of revenues and costs;

- -

- the duration of the whole concession (project + construction + operation/management).

Within this framework, adequate risk transfer from traditional to smart PPP investments needs to be properly executed since inception.

The treatment of risk transfer according to Eurostat rules (Table 1) follows innovative patterns when it is backed by RBF. The availability payment, which is at the base of much controversy in healthcare PF, is fueled by public savings and transferred to the private counterpart only if thoroughly deserved, following pay-for-performance/RBF patterns.

Risk can be softened if linked to performance and results with RBF. This strategy reduces private rents (opportunistic free riding), but also allows for higher compensation whenever it is deserved.

Smart PF sustainability can be partly based on availability payments in which risks are ultimately operational, intrinsically manageable, and dependent on the performance and management of the private partner. Operational performance can be monitored with a comparison with standard costs for the same task.

RBF introduces checks and balances along the delivery chain, encouraging better governance, transparency, and enhanced accountability. The performance of social impact investment programs like healthcare infrastructural investments can be monitored and rewarded with RBF.

Since the 2000s, many scholars have been investigating the reasons behind failures of RBF, with a focus on the public sector [56].

Linking availability payments to RBF can soften affordability issues, transferring a higher risk to the private side. RBF can contribute to reinforcing PPP, aligning private providers with national health policies to attain public health goals.

Since RBF produces higher returns, there is a possible remuneration of the private extra-risk.

Innovation involves administrative processes as reservation systems, IT data management, dematerialization of “paperless” archives and software for equipment maintenance. Product and process innovation are to be combined and synchronized, re-engineering the supply and value chain where healthcare ICT is the converging digital platform. Innovation becomes a driver of cost-cutting policies and “smart” long-term savings. The impact of technology on health expenses is controversial. Technology may increase costs, but it dramatically improves the quality of care and life expectancy. In many applications, technology can, however, contribute to savings, especially for chronic patients that are remotely monitored [57].

To the extent that these savings are measurable, they can be partially converted by National Health Service or other Healthcare bodies into RBF resources that back PF initiatives.

Savings are obtained by reimagining the core function of hospitals as follows:

- -

- increasing labor productivity and process efficiency;

- -

- reducing several categories of costs;

- -

- reducing the duration of hospital stays while preserving the occupancy rate and the quality of health services.

A smart hospital needs significant investments in both tangible and intangible assets (servers, IoT-driven devices, software, information security, etc.) together with the new and effective governance of the IT and other internal processes.

These investments can drive to the following economic and non-economic results:

- -

- optimization of admissions, scheduling, and other processes, resulting in seamless patient flow; the new, more automated processes increase labor productivity and reduce personnel and management costs;

- -

- optimization of assets maintenance (with warning IoT sensors) that diminishes yearly assets costs with quantifiable savings and reduced errors.

- -

- computerized medical record and interconnected clinical information, which ensures a more efficient healthcare thanks to the availability of patient information at all stages; together with networked medical devices, these systems increase the quality of medical treatments reducing the duration of hospital stays, with an impact on daily cost for the patient.

A smart hospital is more than bringing together connected devices on a high-speed networking infrastructure. It means rethinking and fully re-engineering the care process, management system, and governance. Technology and digital capabilities need to be fully integrated into proper day-to-day functioning. These innovations are challenging to implement across a fast-moving, complex organization like a hospital, in a highly networked healthcare system.

In this context, it is essential to identify an applicable operational framework to specific areas of care and an innovative and effective governance model.

Health systems in many countries are moving away from traditional procurement, which is based on clinical preference and price, towards a more holistic perspective that factors in quality and total costs across the product life-cycle. This shift is opening doors for new partnerships with private providers and MedTech companies.

Despite consistent investments in the short run for startup technology, long-term savings can be enormous, regarding the lower mobility of patients, instantaneity of care at home, decreased hospital infections, time savings that can become work activities, etc. The width of the healthcare market is a further propellant for economies of scale and experience.

7. Conclusions

The paper analyzes how Health Information Technology may be implemented in smart hospitals by applying PPP schemes backed by RBF.

This research is concerned with health-related aspects of sustainability, addressing innovative investments. The transition to smart technologies is inevitable and will have a significant impact on healthcare processes and their governance. New actors, networks, and innovation are already challenging consolidated health governance practices.

This study provides some tips to detect and soften the criticalities that concern smart healthcare investments and may affect their long-term viability. Innovative PF schemes may strongly contribute to achieving greater investment sustainability.

Evidence shows that healthcare systems find it difficult to cope with the aging population in the presence of budget constraints driven by the public debt burden. Health-related aspects of sustainability represent a trendy socio-economic issue.

A partial solution to this vital issue is represented by technology, a sustainability tool that is revolutionizing medicine and healthcare. Smart hospitals are the infrastructural cornerstone of this trend, but they raise many unconventional governance concerns.

Healthcare is undergoing a paradigm shift, and governance issues mainly rotate around patients, who are painfully becoming the pivoting stakeholder.

PPP can work if there is a convenience for private investors (with a corresponding public interest). The public health sector is often unprofitable. Therefore, the healthcare PPP/PF, even if of public interest, is not always convenient for private investors. Many public tenders are unable to attract private investors, and so the PPP/PF must be abandoned, going back to traditional procurement or a complete reengineering of the proposal. This is not the case of several investments in smart hospitals.

The thesis of this paper is that whereas the public player maintains a vital role in safeguarding health as a primary public good, it may lack the expertise to promote and run technological—smart—investments.

Hence the growing importance of PPP, where public actors interact with private players, healthcare PPP investments, backed by PF patterns, are consolidated in many developed and catching-up economies, although they preserve some criticalities [58]. Among them, insufficient public-to-private risk transfer can exacerbate public budget concerns.

Smart investments imply higher operational risk, aggravating public-private sharing issues. Public players are so forced to transfer more standard and technological risk to the private actors, whereas the latter need to compensate it with extra-returns, even to soften bankability issues. But extra public payments face the budget pressure.

A solution to this short circuit can be represented by the savings and efficiency gains that technology produces, reshaping consolidated business models.

Material savings are possible and, to settle the risk-reward transfer issues, they must be shared between the public and the private stakeholders. RBF is routinely applied in healthcare to link remuneration to performance, minimizing opportunistic rents. As stated in the report 2014, of the Social Impact Investment Task Force, “there is an urgent need for a revolution in government purchasing, with paying for successful delivery of specific outcomes at its core … ensuring that innovation and effectiveness are incentivized” [28,59].

PPP for technological innovations in health can represent a partial solution to the intricate problem of health sustainability and to their related performance and risk sharing concerns. New technologies may potentially improve access to care and the quality of services. Their rapid evolution and implications on existing procedures, however, increase the risk to adopt technologies that do not bring value for money, raising bankability concerns. Economic and social sustainability should increasingly be patient-centered [9].

Smart hospitals as a concept are a key enabler in driving clinical excellence patient-centric care and operational efficiency [9,60]. This ignites a paradigm shift towards sustainable healthcare models, based on a holistic approach where different targets converge.

Future research avenues should address procurement choices that stimulate private players for the provision of technological innovation. These PPP patterns reshape the financial structure of healthcare social impact investments, changing the role of banks and institutional investors. In an era of budget cuts and staff reductions, financial viability is increasingly challenging and requires innovative solutions that concern smart infrastructures or e-health digital platforms [61,62,63]. Even the governance implications of these choices deserve further scrutiny.

A research limitation, due to the novelty of the topic and consequent lack of empirical evidence, concerns the failure to apply the proposed model to a case study. This is also left to future research.

Author Contributions

The authors equally contributed to the development of this research. Conceptualization: R.M.V., L.M., D.M. and E.G. Data curation: R.M.V., L.M., D.M. and E.G. Formal analysis: R.M.V., L.M., D.M. and E.G. Investigation: R.M.V., L.M., D.M. and E.G. Methodology: R.M.V., L.M., D.M. and E.G. Project administration: R.M.V., L.M., D.M. and E.G. Resources: R.M.V., L.M., D.M. and E.G. Software: R.M.V., L.M., D.M. and E.G. Supervision: R.M.V., L.M., D.M. and E.G. Validation: R.M.V., L.M., D.M. and E.G. Visualization: R.M.V., L.M., D.M. and E.G. Writing—original draft: R.M.V., L.M., D.M. and E.G. Writing—review and editing: R.M.V., L.M., D.M. and E.G.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the four anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. The usual disclaimer applies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acronyms

| BOT | Build Operate Transfer |

| CHF | Congestive Heart Failure |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and diabetes |

| EMHC | Eastern Maine HomeCare |

| ENISA | European Union Agency for Network and Information Security |

| GIIN | Global Impact Investing Network |

| HIS | Hospital Information Systems |

| HIT | Health Information Technologies |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technologies |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IT | Information Technology |

| LIS | Laboratory Information Systems |

| MedTech | Medical Technology |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PACS | Picture Archiving and Communication Systems |

| PF | Project Financing |

| PPP | Public Private Partnership |

| RBF | Result Based Financing |

| SPV | Special Purpose Vehicle |

| SROI | Social Return on Investment |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| U.S. | United States |

References

- Hueskes, M.; Verhoest, K.; Block, T. Governing public–private partnerships for sustainability: An analysis of procurement and governance practices of PPP infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; McLeod, A. Do health information technology investments impact hospital financial performance and productivity? Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2011, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Adbi, A.; Singh, J. Outcome Efficiency in Impact Investing Decisions; INSAED Working Paper Series; SSRN: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Agency for Network and Information Security “ENISA”. Smart Hospitals. Available online: http://www.enisa.europa.eu (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- The World Bank. Benin—Health System Performance Project. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/610531528123982706/Benin-Health-System-Performance-Project (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Bullen, M.; Hughes, T.; Marshall, J.D. The Evolution of Nice Med Tech Innovation Briefings and Their Associated Technologies. Value Health 2017, 20, A595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munksgaard, K.B.; Majbritt, R.; Evald Clarke, A.H.; Nielsen, L.S. Open Innovation in Public-Private Partnerships? Ledelse Erhv. 2012, 77, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner, D. Public-Private Partenerships Models for Science, Technology and Innovation Cooperation. J. Knowl. Econ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro Visconti, R.; Martiniello, L. Smart Hospitals and Patient-Centered Governance. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2019, 16, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.; Ells, C.; Thombs, B.D.; Clarke, D. Defining elements of patient-centered care for therapeutic relationships: A literature review of common themes. Eur. J. Pers. Cent. Healthc. 2017, 5, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Triberti, S.; Graffigna, G.; Libreri, C.; Serino, S.; Hibbard, J.; Riva, G. eHealth for Patient Engagement: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2016, 6, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission of Safety and Quality in Healthcare. Patient-Centered Care: Improving Quality and Safety by Focusing Care on Patients and Consumers. Available online: https://safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/PCCC-DiscussPaper.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Rantala, K.; Karjialuoto, H. Value co-creation in healthcare: Insights into the transformation from value creation to value co-creation through digitization. In Proceedings of the 20th International Academic MindTrek Conference, Tampere, Finland, 17–18 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Larocca, A.; Moro Visconti, R.; Marconi, M. First-Mile Accessibility to Health Services: A m-Health Model for Rural Uganda; Working Paper; SSRN: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- David, G.; Saynisch, P.A.; Smith-McLallen, A. The Economics of Patient-Centered Care. J. Health Econ. 2018, 59, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, A.; McKee, M.; Basu, S.; Stuckler, D. The political economy of austerity and healthcare: Cross-national analysis of expenditure changes in 27 European nations 1995–2011. Health Policy 2014, 115, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, R.; Banerjee, S. Effects of State Level Government Spending in Health Sector: Some Econometric Evidences. Rev. Manag. 2018, 8, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosis, S. Public strategies for improving eHealth integration and long-term sustainability in public health care system: Finding from an Italian case study. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2018, 33, e131–e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acerete, B.; Stafford, A.; Stapleton, P. Spanish healthcare Public Private Partnerships: The ‘Alzira model’. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2011, 22, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amy, S.; Brisbois, B.; Zerger, S.; Hwang, S.W. Social impacts bonds as a funding method for Health and social programs: Potential area of concerns. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 210–215. [Google Scholar]

- Laing, C.M.; Moules, N.J. Social return on investment: A new approach to understanding and advocating for value in Health. J. Nurs. Adm. 2017, 47, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Torre, M.; Calderini, M. Social Impact Investing beyond the SIB; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. Volume—To Value-Based Care: Physicians Are Willing to Manage Cost but Lack Data and Tools. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/us/articles/4628_Volume-to-value-based-care/DI_Volume-to-value-based-care.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Aduragbemi Oluwabusayo, B.T.; Barbara, M.; Ameh, C.; Nynke, V.D.B. Social Return on Investment (SROI) methodology to account for value for money of public health interventions: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 582. [Google Scholar]

- Shaoul, J.; Stafford, A.; Stapleton, P. The cost of using Private Finance to Build Finance and Operate Hospitals. Public Money Manag. 2008, 28, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerete, B.; Stafford, A.; Stapleton, P. New development: New Global health care PPP developments—A critique of the success story. Public Money Manag. 2012, 32, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro Visconti, R. Healthcare Public-Private Partnerships in Italy: Assessing Risk Sharing and Governance Issues with Pestle and Swot Analysis. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2016, 13, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro Visconti, R.; Doś, A.; Pelin Gurgun, A. Public-Private Partnerships for Sustainable Healthcare in Emerging Economies. In The Emerald Handbook of Public-Private Partnerships in Developing and Emerging Economies: Perspectives on Public Policy, Entrepreneurship and Poverty; Leitão, J., Sarmento, E.M., Aleluia, J., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2017; Chapter 15; pp. 407–437. [Google Scholar]

- Moro Visconti, R. Multidimensional principal–agent value for money in healthcare project financing. Public Money Manag. 2014, 34, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esty, B.C.; Chavich, C.; Sesia, A. An Overview of Project Finance and Infrastructure Finance-2014 Update; Harvard Business School Industry Background Note; SSRN: New York, NY, USA, 2014; p. 214083. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, J.M.; Alves, P.P. The Choice between Project Financing and Corporate Financing: Evidence from the Corporate Syndicated Loan Market. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2876524 (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Bayar, O.; Chemmanur, T.J.; Banerji, S. Optimal Financial and Contractual Structure for Building Infrastructure Using Limited-Recourse Project Financing. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2795889 (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Moro Visconti, R. Evaluating a Project Finance SPV: Combining Operating Leverage with Debt Service, Shadow Dividends and Discounted Cash Flows. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2013, 1, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, S. Project Finance in Theory and Practice—Designing, Structuring, and Financing Private and Public Projects, 2nd ed.; Academic Press Advanced Finance—Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brealey, R.A.; Cooper, I.A.; Habib, M.A. Using Project Finance to Fund Infrastructure Investments. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 1996, 9, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esty, B.C. The Economic Motivations for Using Project Finance; Mimeo: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Esty, B.C. Modern Project Finance, a Case Book; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Esty, B.C. Why Study Large Projects? An Introduction to Research on Project Finance. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2004, 10, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corielli, F.; Gatti, S.; Steffanoni, A. Risk Shifting through Nonfinancial Contracts: Effects on Loan Spreads and Capital Structure of Project Finance Deals. J. Money Credit Bank. 2008, 42, 1295–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Manuals and Guidelines. Manual on Government Deficit and Debt, Implementation of ESA 2010. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/7203647/KS-GQ-16-001-EN-N.pdf/5cfae6dd-29d8-4487-80ac-37f76cd1f012 (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Moro Visconti, R. Big Data-Driven Healthcare Project Financing; Working Paper; SSRN: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, K.G. Delivering Innovation in Hospital Construction: Contracts and Collaboration in the UK’s Private Finance Initiative Hospitals Program. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2009, 51, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirkunova, E.K.; Kornilova, D.A.; Pschenichnikova, J.S. Research of Instruments for Financing of Innovation and Investment Construction Projects. Procedia Eng. 2016, 153, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Reeves, D.; Kontopantelis, E.; Middleton, E.; Sibbald, B.; Roland, M. Quality of Primary Care in England with the Introduction of Pay for Performance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strategic Finance. Managing Healthcare Cost and Value. Available online: https://sfmagazine.com/post-entry/january-2017-managing-healthcare-costs-and-value/ (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Henjewele, C.; Sun, M.; Fewings, P. Critical parameters influencing value for money variations in PFI projects in the healthcare and transport sectors. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2011, 29, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savedoff, D.W. Basic Economics of Results-Based Financing in Health; Social Insight: Bath, ME, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nasira, J.A.; Hussainb, S.; Danga, C. An Integrated Planning Approach towards Home Health Care, Telehealth and Patients Group Based Care. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2018, 117, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, E.; Cusack, C.; Hook, J.; Vincent, A.; Kaelber, D.C.; Bates, D.W.; Middleton, B. The value of provider-to-provider telehealth. Telemed J. Health 2008, 14, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osservatori.net—Digital Innovation. Digital Innovation in Healthcare Observatory 2017–2018 (Italy). Available online: https://www.osservatori.net (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Darmanin, A.; Gaur, C. Benefits of Telehealth: Reducing Hospitalization for Older Adults. In Proceedings of the Student-Faculty Research Day, Seidenberg School of CSIS, White Plains, NY, USA, 1 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Osservatorio Nazionale Sulla Salute Nelle Regioni Italiane. Rapporto Osservasalute. 2017. Available online: http//www.osservatoriosullasalute.it (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Long-Term and Post-Acute Care Providers Engaged in Health Information Exchange: Final Report. Telehealth Cost Considerations; Report 2013; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/ (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Società di Telemedicina. Telemonitoraggio Medico e la Teleassistenza Domiciliare Contro il Fenomeno Crescente Della Cronicità. Available online: http://www.panoramasanita.it/2014/06/18/elemonitoraggio-medico-e-la-teleassistenza-domiciliare-contro-il-fenomeno-crescente-della-cronicita/ (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Hu, H.; Chen, J.; Shen, B. How to Become a Smart Patient in the Era of Precision Medicine? In Healthcare and Big Data Management; Shen, B., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; Volume 1028, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Van Thiel, S.; Leeuw, F.L. The Performance Paradox in the Public Sector. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2002, 25, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.K. Technology and Healthcare Costs. Ann. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2011, 4, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro Visconti, R. Public Private Partnerships, Big Data Networks and Mitigation of Information Asymmetries. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2017, 14, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Impact Investment Task Force Report Impact Investment: The Invisible Heart of Market. 2014. Available online: https://impactinvestingaustralia.com (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Arthur D Little. Building the Smart Hospital Agenda. Available online: http://www.adlittle.com/sites/default/files/viewpoints/ADL_Smart%20Hospital.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Tsasis, P.; Agrawal, N.; Guriel, N. An Embedded Systems Perspective in Conceptualizing Canada’s Healthcare Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, L.; Testa, M.; Marino, V.; Singer, P. Engagement in Healthcare Systems: Adopting Digital Tools for a Sustainable Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggini, M.; Cosimato, S.; Nota, F.D.; Nota, G. Pursuing Sustainability for Healthcare through Digital Platforms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).