1. Introduction

Chinese housing sales market has flourished since the housing system was reformed, but the rental market has been lagging behind [

1]. In China, while the rate of homeownership reached over 80% in 2016, the leasing rate was less than 20%. The number of renters in China is only approximately 0.166 billion, among which, young people constituted about 74% of the total renters [

2]. Young people are the main force of China’s renting population. China’s homeownership rate is higher than those of developed countries or regions, which are mostly around 65%. In terms of the leasing rate, Germany, for instance, has reached more than 45% [

3]. The leasing and purchasing markets in China are severely out of balance. According to the data from the National Bureau of Statistics, the housing price in China had more than doubled from 2007 to 2016 [

4], which placed middle and low-income citizens under great pressure to own their houses. However, because of the capital gains from housing, public services and traditional Chinese views, many people still persisted in purchasing houses even though they can hardly afford them [

5]. This situation affected the development of the rental market, and further restricted the prosperous development of the Chinese housing market. Therefore, dealing with the unbalanced circumstances between leasing and purchasing of homes is urgent in order to achieve the Chinese housing reform’s goal of simultaneously developing both. ‘The same rights of lease and purchase’ is an emerging motivation to promote the development of the rental market, which implies that purchasers and renters should enjoy the same public rights, including children’s educational rights, community services and other equal services. This policy not only protects the rights and interests of renters but also promotes social equality and increased quality of life [

6]. Furthermore, it conforms to the social requirements and the principles of the World Commission on Environment and Development on sustainable development, which are beneficial to social sustainable development.

Rental behavior is a kind of green consumer behavior and has various elements that affect its realization. Sun believes personal factors of consumers, such as environmental knowledge, values and altruism, and contextual factors, such as culture, have a significant effect on low-carbon consuming behaviors [

7]. Previous studies on housing rental behavior were mostly policy-oriented and focused mainly on macro-level research, such as on economics, institutions and housing stock [

8,

9], whereas few studies on the micro level focused on factors that affect individual behaviors. Thus, factors that affect consumers’ willingness to rent and the relationship between these factors and rental behaviors are still uncertain. This study adopts the psychosocial model of planning behavior theory to study the relationship between consumers and rental behaviors.

Particular features of Chinese renting behavior are as follows. First, the renting population is mainly concentrated in the first and second-tier cities. The proportion of the renting population is generally proportional to the urban population size and economic development level. Second, the demands of renting housing are concentrated in the youth group. Third, there is discrimination against rented families in the system. Renting and self-occupied families cannot enjoy the same treatment in basic public services such as children’s schooling, employment, social insurance, and medical care. Previous studies on rental behaviors are mainly focused on normal tenants and lack of research on special groups (such as elderly or young groups and so on) [

8,

10], especially ignoring the views and attitudes of young people. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the age of young people extends from 19 to 34, and the number of young Chinese people occupies approximately 21.36% of the total population. Due to the imbalance of economic conditions, incomes of young people are different in different cities. According to the Sixth National Census, 86% of young people chose to rent housing, and the average monthly income was less than 10,000 yuan, accounting for 70% [

11]. Young people have certain distinct features compared with other groups. Most of them have low incomes and low savings. Increasing housing prices have resulted in enormous economic pressure for this group. Moreover, obtaining higher education increased their ability for accepting new ideas, including new policies and forms of consumption. In the context of Chinese culture and social norms, renting is regarded as a new concept. On the other hand, the youth group has experienced unstable career development and highly mobile workplaces. As a result, this group is unwilling to be bound by the need for homeownership. The demand for renting even exceeds the demand for purchasing. Renting a house reduces such pressure on young groups and allows them to enjoy equal access to public services. Overall, this study mainly focuses on young people’s preference towards rental behaviors.

To supplement the deficiency in previous research, this study aims to analyze the influential factors that affect the rental housing behavior of young consumers. Three reasons explain the Chinese context as an effective research laboratory. First, China is a country with a large population that incurs a huge demand for housing. Rental housing is significant for achieving global sustainable development. Second, China is one of the developing countries and the results of this study will provide other countries with valuable insights. Third, most of the previous studies on rental behaviors did not separately study young consumers as a group. This study will fill the gap by investigating their adopted intentions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Renting and Sustainable Development

In September 2015, the United Nations adopted the globally sustainable development goals for 2016–2030, which means sustainable development will further become the central axis principle for guiding global economic growth [

12]. Sustainable development is defined by the WCED as the ability to meet current needs without harming the interests of future generations and has three dimensions: the economy, environment and society [

13,

14]. At the economic level, renting can promote the steady development of the real estate market, which can promote the balance of the purchasing and leasing market. In China, spending on housing and housing services has grown to reach 8% of GDP, and rapid rises in housing prices have led to an increase in household financial pressures and real estate bubbles [

15], which can even lead to a collapse that triggers a financial crisis [

16]. Renting housing can reduce the need to purchase housing, which is beneficial to controlling housing prices. Thereby, renting can promote sustainable economic development. At the environmental level, buildings have a major impact on energy use and carbon emissions [

17]. China allocates 1.6–2.0 billion square meters of buildings each year, accounting for nearly 40% of the total number of new buildings in the world [

18]. Renting can reduce the need for new buildings, which will reduce housing supply according to the regular pattern of market development. Thereby, resource consumption and carbon emissions will decrease due to the reduction of new buildings. Therefore, renting can contribute to the reduction of carbon emissions and energy use, which is conducive to environmental protection and sustainable development. At the social level, social sustainability involves the promotion of social harmony and equity and the improvement of the quality of life of all segments of the population [

19,

20]. In the context of housing, social sustainability enables the equitable distribution of resources and opportunities, and constructs living apartments that are affordable, safe and healthy. Moreover, social sustainability helps residents integrate into the extensive social-spatial system [

21,

22]. Renting can solve the housing problems of residents, which can guarantee people’s basic living conditions. The social dimension of sustainability remains a critical condition because of the importance of housing demand and livelihoods [

23].

In 1988, China underwent housing system reform, shifting from a welfare-oriented housing system to a market-oriented one [

24,

25]. The commodity attribute of housing has been given considerable attention, and housing is being gradually used as an investment tool. In addition, accessing public services is often tied to home ownership in China. For example, home ownership is the necessary condition for children to attend the school that corresponds to their neighborhood. Home ownership is also associated with enjoying community care services [

26]. A traditional Chinese concept also states that ‘there is room to have a home’, increasing people’s willingness to buy a house even if they must spend most of their income on loans. This situation has a detrimental effect on the social economy [

27,

28]. Although China has abundant public housing, the housing stock cannot keep up with the huge population, fast urbanization and the increasing needs of the public. Many people need to rent apartments to deal with housing-related problems. To solve this problem, China’s ‘13th Five-Year Plan’ clarifies that a housing system with a simultaneous development of lease and purchase will be established. In this context, the ‘the same rights of lease and purchase’ was proposed as a new measure to promote the balance between leasing and purchasing homes [

29]. Renting could guarantee everyone, including the poor, an affordable, tidy and suitable house to live in. Citizens can assert and exercise their basic rights [

30]. Thus, renting is conducive to enhancing social harmony and improving the quality of life across different social strata, thereby achieving sustainable social development [

21].

2.2. Factors for Housing Selection

Housing choices are an essential part of life, and the factors influencing these choices are diverse [

31,

32]. Before the 21st century, the initial empirical study on housing choices focused on the impact of family characteristics [

33], arguing that family status and size had a significant effect on housing choices. Zhou believed that public housing is more likely to be chosen by those with lower incomes, larger family sizes and more urban relatives [

34]. According to Wang’s research, marital status and parental assets were emphasized as the most important driving forces for housing choices. Marital status and monthly income are also crucial factors in renting intentions [

31]. However, in the first decade of the 21st century, many scholars explored the impact of population, housing affordability, psychological factors, institutions and policies [

35,

36]. For example, Zheng’s study on the Hong Kong leasing market concluded that the temporary income shock had a more substantial influence on the demand for renting [

37]. Yan Liu verified that purchasing decision is highly correlated with the socio-economic conditions of consumers, and that ‘fixed income’, ‘child education’, ‘credit level, ‘immediate children’ and ‘marriage’ are five factors affecting housing choice [

2].

Studies from the first decade of the 21st century have confirmed that the cultural background could affect consumers’ renting intentions [

38]. Yates and Oliveira also reached similar conclusions, arguing that cultural differences play a critical role in housing choices [

39]. Zhou considered commuting distance to be an important factor affecting housing choices [

40]. Fisher et al. obtained similar results. Zhou established a Cobb-Douglas model that used housing area and commuting distance as primary monitoring variables and determined that commuting distance, community environment and allocation level play essential roles in housing decision-making [

41]. The model comprehensively considers the needs of residents and has considerable significance for future research. In his study of the elderly population, Lim concluded that family relationships and values of life are crucial to their housing choices. The housing choices of the elderly involve being geographically closer to their children [

42]. In recent years, some scholars have studied the willingness of rental property tenants to pay for energy efficiency improvements. Banfi et al. and Jongho Im stated that energy-efficient buildings attract more renters despite the need to pay additional rent. Based on the discussions in existing literature, this study aims to analyze renting behaviors that are closely connected to sustainability performance.

3. Theoretical Model and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Modified TPB

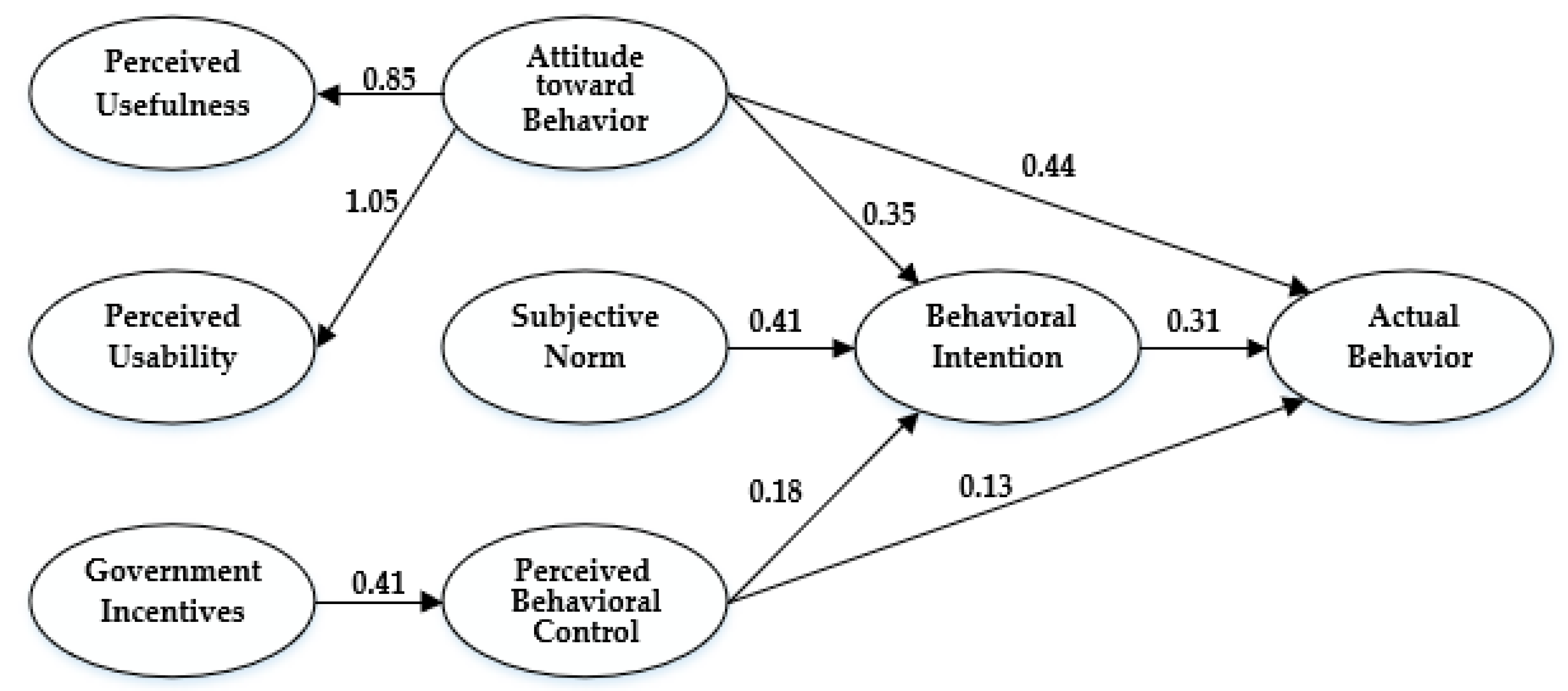

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) was proposed by Ajzen in the1980s, and is widely used to predict behavioral intentions and actual behaviors in the field of social psychology [

43]. The TPB framework determines actual behavior (AB) by examining behavioral intention (BI). Ajzen proposed three determinants that explain behavioral intention, namely, attitude towards behavior (ATT), subjective norm (SN) and perceived behavioral control (PBC) [

44]. The cognitive and emotional basis of the three determinants is obvious belief, including behavioral belief, normative belief and control belief [

45]. In their respective populations, behavioral belief is defined as the subjective identification of individuals and the assessment of outcomes resulting from the behavior [

46]. Normative belief is a person’s perception of other people’s expectations of their belief. Beliefs produce behavioral control when actual behaviors are implemented [

47]. The technology acceptance model (TAM), namely, perceived usefulness (PU1) and perceived usability (PU2), is the most commonly utilized theory for evaluating technology or new information acceptance [

48]. TAM considers the results of external factors with beliefs, attitudes and intentions but does not account for social influence in the adoption of new things [

49]. The appeal of TAM lies in that it is both specific and parsimonious, and displays a high level of predictive power with regard to the adoption of technology or new developments. Several studies have concluded that government incentives (GI) have a significant effect on green consumer behavior [

50]. Therefore, in measuring their intention to rent, additional constructs should be considered to extend the basic TPB model.

The reasons for adopting TPB are that it was not only the most common applied psychology theory to predict individual behavioral intentions [

51], but also was one of the most frequently mentioned theories in the field of green consumerism. At present, TPB has been applied to predict consumer intentions and behavior in a wide range of areas, including electric vehicles [

52], green hotels [

53] and energy conservation. TPB is already one of the most commonly used theories for explaining green consumption behavior. Hence, the prediction of renting behavior as as an example of green consumption behaviors can use TPB theory. In traditional Chinese concepts, renting is a new perspective on consumption. Using TAM to evaluate the acceptance of renting is appropriate in this case. Owing to theoretical compatibility and potential complementarity, TAM must be considered to fully enhance the explanatory power of TPB. As claimed by Taylor and Todd, combining TAM and TPB can adequately define an individual’s behavior with regard to accepting new things [

54]. For example, Chen explores factors that influence a driver’s intention to use an Electronic Toll Collection (ETC) in Taiwan by combining TAM and TPB models [

55]. Hence, TAM and TPB can be combined to explore the factors affecting renting. The conceptual model of the improved TPB is shown in

Figure 1.

3.2. Hypothesis Development

3.2.1. Attitude toward Behavior, Subjective Norm and Behavioral Intention

In this study, PU1 and PU2 are used as antecedent variables to explain ATT. ATT refers to the positive or negative feelings that individuals hold when taking a particular behavior [

56,

57]. PU1 as an antecedent variable of attitude toward behavior represents the convenience and security of renting [

58], including for providing assistance with children’s education, economic pressure, and residence flexibility. Compared with buying a house, renting a home can save costs and reduce financial burdens. PU2 as an antecedent variable of ATT refers mainly to the degree of difficulty perceived of renting [

59]. Examples of these difficulties include the degree of difficulty in finding satisfactory listing, a more straightforward operation of the rental platform, and a more flexible rental terms and whether renters choose to live nearby according to their needs. Subjective norm refers mainly to perceived social pressure to perform one behavior [

60,

61]. The subjective norm of renting consists of three components, including government support, better network evaluation and the persuasion of friends or family members. Government support is conducive to the formation of good social pressures to promote the willingness of renting. Better network evaluation and the persuasion of friends or family members can promote normative beliefs about renting. If people hold the belief that they could perform one behavior, they are more likely to persevere to achieve success. Behavioral intention (BI) refers to the judgment and psychological tendency of an individual. When the actual control conditions are sufficient, the behavioral intention directly determines the actual behavior [

44]. As stated above, we put forward the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Attitude toward behavior has a positive effect on behavioral intention.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Attitude toward behavior has a positive effect on actual behavior.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Subjective norm has a positive effect on behavioral intention.

3.2.2. Perceptual Behavior Control, Behavioral Intention and Actual Behavior

Ajzen proposed that perceived behavioral control (PBC) is an additional determinant of intentions and behavior. PBC refers to the degree of difficulty perceived, which derives from control beliefs and perceived power [

62]. Control beliefs refer to the individual’s belief in his or her control over one behavior, which is the basis of PBC and perceived power inclined to promote or hinder the performance of the behavior [

43]. The perceived behavioral control of renting includes operating conditions, rent levels and mental stability. Government incentives are the antecedent variables of PBC because the government plays a crucial leading role in promoting the rental market. In the context of ‘the same rights of lease and purchase’, the rental market will inevitably experience issues, such as rising rental rates and disruptions to the status quo of enrolment in prestigious schools, which may result in additional incremental costs. Profit-driven developers often transfer other costs to consumers. Consumer enthusiasm for buying a house will not diminish even in the absence of financial compensation and a bright future. Therefore, government incentives are particularly relevant in promoting the development of the rental market to make young consumers inclined to rent a home through effective subsidies such as economic subsidies, tax incentives, preferential loan policies and increased housing supply. According to behavioral decision theory, individuals rely more on intuition than logic analysis when identifying and discovering problems. Thus, the PBC of renting is more intense than purchase; for example, the comfort of living in renting a house, the harmony within the neighborhood and the degree of government economic incentives. Consumers will be more willing to rent in the face of favorable factors to consumers. Based on the above discussion, we propose the hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Government incentives have a positive effect on perceived behavioral control.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Perceived behavioral control has a positive effect on behavioral intention.

Hypothesis 6 (H6): Perceived behavioral control has a positive effect on actual behavior.

3.2.3. Behavioral Intention and Actual Behavior

According to organizational behavior theory, the actual behavior of individuals depends on the dual roles of PBC and BI. The stronger the individual’s willingness of a certain intention, the higher it will be implemented. The actual behavior in this paper refers to the adoption of renting behavior and suggestion for more consumers to rent. When the external control factors are consistent with the internal behavioral intentions, the actual behavior can be implemented. As stated above, the article proposes the following assumption:

Hypothesis 7 (H7): Behavioral intention has a positive effect on actual behavior.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. City Background

The research was conducted in Jinan, the capital of Shandong Province, a large economic province on the east coast of China. Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Jinan has been the political, economic and cultural center of the region. According to the Statistics Bureau of Jinan City, the total regional GDP of the city in 2017 was 720.19 billion RMB and the resident population was 7.23 million, an increase of 1.22% over the previous year. The annual average population is 6.38 million, which is an increase of 14% from the previous year, and the per capita disposable income of urban residents is 46,642 RMB. During the same year, 189,000 new urban jobs were created in Jinan, and the annual number of local university graduates, including the 0.1 million people working in Jinan, reached 0.178 million people. During the same year, 189,000 new urban jobs were created in Jinan [

63]. As the capital city of a significant economic province, Jinan has the strength to attract young people to come to the city to find work. The number of renters is up to 150,000 people per year in Jinan, mainly including non-resident permanent residents, such as migrant workers and newly employed college students. Among them, the number of people is under 35 years old, accounting for 86% of renters [

63]. In 2017, The rental housing stock is approximately 370,000 in Jinan [

63]. Therefore, there are sufficient rental housing to meet living needs in Jinan.

The Jinan government has actively introduced relevant policies to encourage the development of rental housing to ensure the provision of basic living requirements of the urban population. In 2018, the Jinan government officially issued the Implementation Opinions of the Jinan Municipal Government on Cultivating and Developing the Housing Leasing Market. The report suggested that vacant office buildings be turned into rental properties, which would increase the number of rental properties. Moreover, this approach will encourage real estate development and property service companies to actively develop leasing businesses by intensifying their policies and strengthening the supervision of housing leases to promote the development of the rental market. Simultaneously, the Jinan government actively responded to the policy of ‘the same rights of lease and purchase’, and the first pilot project was included in the list of key projects at the municipal level. In 2017, Jinan became the first experimental site for the conversion of old kinetic energy to new kinetic energy. The conversion of old kinetic energy to new kinetic energy involves cultivating new kinetic energy, transforming old kinetic energy, and forming a new impetus for economic and social development. As part of sustainable housing, renting can help to reduce the vacancy rate, which makes a difference for resource utilization and sustainable development. Renting meets the fundamental requirements of new and old kinetic energy conversion.

In summary, Jinan is a good laboratory for this research for the following reasons. First, the demands of renting are strong due to the growing population in Jinan. Simultaneously, the rental housing supply in Jinan is large enough to meet demand. Second, Jinan has an excellent policy background and government support in the development of the rental market, which can encourage more people to choose to rent housing. Third, previous studies on intentions and behavior regarding renting were mentioned previously in Nanjing and Beijing [

64], which are first-tier cities. To our knowledge, there was little research in the second-tier cities, and therefore the findings can be extended to the mass cities in China. Therefore, this study targets the young groups in Jinan as the research object to clarify renting intentions.

4.2. Structure Equation Model

The structural equation model (SEM) has been widely used in numerous research areas since the 1980s and has been proven to be effective in psychological and behavioral studies [

65]. The SEM is used to test the relationship between observed and latent variables by analyzing the collected data. This method is an important tool in identifying the relationship between key factors [

66]. For example, Ju adopted SEM to identify the impact factors of the logistics service supply chain for sustainable performance [

67]. Donald applied SEM to analyze the factors affecting the transport mode used by commuters [

68]. SEM has been widely used in the field of multivariate data analysis to compensate for the shortcomings of traditional statistical methods. Therefore, SEM was used to analyze the hypotheses in this study. AMOS20.0 software was adopted for applying SEM during the research process.

4.3. Questionnaires

This study collected data by using a questionnaire survey. There were seven latent variables and 22 observed variables in this study. Latent variables mainly include perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, government incentives, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, behavioral intention and actual behavior. To ensure rationality, the items were mainly adapted from previous studies. In this study, the construct of PU1 was adopted from Czerniak [

3], Zhou [

34] and Davidson [

69], and evaluated through three items of PU11-PU13. Items for PU2 were adapted from Zhou and Fisher [

40,

70]. Items for GI were selected from Zheng [

37], Fisher and Zhang [

71,

72]. Items for SN were adapted from Chen and Liobikiene [

73,

74]. Items for PBC were adapted from Tian and Armitage [

36,

75]. Items for BI were adapted from Zhou and Makinde [

34,

38]. Items for AB were adapted from Zheng and Wang [

37,

76].

A seven-point Likert scale is used in our questionnaire survey, where one signifies ‘strongly disagree’ and seven indicates ‘strongly agree’ [

77]. Considering that the measurement items should be easy to understand and answer, we needed to do consumer forecasting first. We modified a few survey items and adjusted some descriptions based on the forecasting provided by consumers.

Table 1 establishes the measurement scales in the formal questionnaire for data collection.

4.4. Data Collection

The questionnaire was distributed through two channels. The first is an online survey, which sends the questionnaire survey link to consumers aged 18–34 through a web platform such as WeChat, QQ and so on. The snowball sampling method was also adopted. Firstly, the respondents were randomly selected. Then, the respondents distributed the questionnaire to other respondents who meet the overall characteristics of the sample, such as their relatives and friends. This method can guarantee sample characteristics and save money. The second is a direct-access questionnaire survey method conducted by five well-trained investigators. Potential respondents were informed of the aim of the survey and policy of ‘the same rights of lease and purchase’. The respondents completed the written questionnaire after they agreed to participate in the study. The direct-access questionnaire survey method can provide good control of the sample but it is time consuming and requires additional effort. Online surveys can save time and costs but are uncertain to provide ideal respondents. Therefore, this study uses a combination of the two survey methods.

To ensure the questionnaires accurately reflected the residents’ acceptance of renting behaviors, the potential research objects in this paper include, but are not limited to, government officials, office workers and college students that are about to graduate from Jinan. The survey lasted for two months from August 2018 to October 2018. A total of 150 questionnaires were distributed on the spot and 260 were distributed online. Finally, a total of 353 questionnaires were obtained, including 121 paper questionnaires and 232 questionnaires from the online questionnaire. This research covers young people of different ages, occupations and incomes, most of which are potential renters. A detailed sample description is shown in

Table 2. After data screening, 296 valid questionnaires were finally obtained. Kline proposed that the sample size must be at least 10 times per item. The present study has a total of 22 items and the sample size is at least 220, thus meeting the requirements [

78].

5. Results

5.1. Measurement Model: Reliability and Validity

Reliability analysis refers to the degree of consistency of the results of different test measurements. At present, Cronbach’s α is utilized to measure internal consistency in the academic community. The α coefficient is between 0–1; the higher the α coefficient, the better the internal consistency of the scale [

79]. Generally, all results are greater than 0.7. If the α coefficient is above 0.8, then the analysis is deemed to have a high degree of reliability [

80]. This study used SPSS20.0 to test the reliability of the seven latent variables and 22 observed variables of the questionnaire. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the seven latent variables ranged from 0.715 to 0.905 (see

Table 2 for details). The overall Cronbach’s α coefficient of the questionnaire is 0.910, and both the whole and the part meet the requirements, indicating that the reliability of the questionnaire is ideal.

The goal of the questionnaire is to conduct measurements which have adequate validity and to obtain useful conclusions. The higher the validity, the higher the realism of the survey [

80]. Validity analysis includes mainly content and structural validity, and structural validity consists of both convergent and discriminant validity. Content validity generally affirms the factor loadings after orthogonal rotation. If the factor loading is greater than 0.5 after the orthogonal rotation, then the content validity is good [

81]. The factor loading of the index is between 0.556 and 0.866, which indicates that the questionnaire has adequate content validity.

Convergent validity is measured further using average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) [

82]. The AVE scores need to be higher than 0.5 and the CR scores need to be higher than 0.6 [

83]. This paper uses Amos 20.0 to calculate the AVE and CR scores. The AVE for seven latent variables is higher than 0.5 and the CR scores range from 0.703 to 0.905, which expresses good convergent validity. The above values are shown in

Table 3.

The square root of AVE for each construct was generally believed to be higher than its correlations with other constructs, which can represent adequate discriminant validity.

Table 4 shows that the square root of each variable AVE is greater than the correlation coefficient between the variables, and thus shows that the questionnaire constructed has reasonable validity.

Through the reliability and validity analysis of the above questionnaires, the reliability and validity of the questionnaire are shown to be good and the next step of structural equation modeling can be carried out.

5.2. Model Test

5.2.1. External Quality Test

According to the model hypothesis, the AMOS 20.0 was used to fit the model. According to the standard in the previous studies [

84,

85], we test the goodness-of-fit measures. Initially, most of the index values reached the critical standard, indicating that the model basically meets the requirements. However, there are still a few indicators that are not up to standard, such as GFI = 0.881, AGFI = 0.872, NFI = 0.888 and RFI = 0.869. The model has not reached the ideal state and needs to be corrected. Hatcher pointed out that most models are difficult to use to meet all fit standards the first time due to data bias [

86]. The model is modified several times according to the Model Fit index, thus, CFA was conducted again on the modified theoretical framework. The comparison results between the initial and refined model are shown in

Table 5.

Figure 2 presents the action path of renting.

5.2.2. Intrinsic Quality Test

The combined reliability is utilized to measure internal consistency among items. Bagozzi and Yi adopted the lower standard and believed that the combined reliability is above 0.6, which means that the combined reliability of latent variables is adequate [

87]. In this paper, the formula

is used to find the combined reliability of each latent variable. The results are shown in

Table 1. The combined reliability of each latent variable is between 0.703 and 0.905, which is greater than 0.6, indicating that the intrinsic quality of the model is right.

= combined reliability, λ = normalized parameter of the observed variable on the latent variable (factor loading), θ = error variation of the indicator variable.

5.3. Hypothesis Verification

Table 6 shows the results of the hypothesis test. All hypotheses were supported. This paper uses the standardized path coefficient to analyze the model empirically. Attitude toward renting (β = 0.35, t = 4.529,

p < 0.001) was significantly related to renting intentions, thereby, H1 was supported. Attitude toward renting (β = 0.44, t = 6.143,

p < 0.001) has a significantly positive impact on actual behavior. Thus, H2 was supported. Moreover, subjective norm (β = 0.41, t = 4.946,

p < 0.001) and perceived behavioral control (β = 0.18, t = 2.711,

p < 0.01) were found to have a strong positive effect on renting intention, supporting H3 and H5. Governmental incentives (β = 0.41, t = 6.073,

p < 0.001) reported a significant positive effect on PBC. Thus, H4 was supported. Perceived behavioral control (β = 0.13, t = 2.458,

p < 0.05) has a significantly positive impact on actual behavior for renting, which supports H6. Intention (β = 0.31, t = 4.003,

p < 0.001) has a significant effect on actual behavior for renting, which supports H7.

6. Discussion

Through the analysis of the above structural equation model, we concluded that government incentives have a significant positive impact on perceived behavioral control. Attitudes toward behavior, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control of renting have a positive influence on behavioral intentions, and indirectly affect actual behavior through behavioral intentions. Ajzen believed the three factors affecting individual behavior are the attitudes toward behavior, subjective norms and perceived behavior control [

44], which is consistent with the conclusion of this paper.

Attitudes toward renting have been observed to have the most considerable influence on behavioral intention, indicating that attitude toward behavior, that is, perceived usefulness and perceived usability, is among the most critical determinants for young consumers’ renting behavior. This is similar to the findings in previous studies that perceived that green values have a significant impact on the loyalty of public bicycle systems through sustainable modified TAM and TPB [

73]. Moreover, the conclusion is consistent with that of Justin Paul, which indicates that the attitude towards the behavior (ATT) considerably influences the prediction of green product consumption [

88,

89]. Therefore, perceived usefulness and perceived usability are relevant factors in green consumer behavior. Behavioral intention also affects actual behavior (0.31), indicating that when the willingness to rent is strong, young consumers will rent, which is related to the personal qualities of the younger generation in China. This conclusion is not entirely consistent with the finding of Zheng partly due to the different resources of the respondents [

89].

Subjective norms and perceived behavioral control had a direct positive influence on renting intention, whose path coefficients are 0.41 and 0.18, respectively, reflecting that the external subjective normative pressure has more noticeable effects on behavioral intention compared with perceived behavior control. Interestingly, this conclusion is precisely the opposite of Mäntymäki’s research on teenagers indulging in the virtual world [

90]. We suspect the reason behind this difference is the difference in research subjects. Indulging in the virtual world is negative behavior and needs to be restricted. In comparison with the pressure from public opinion, the personal perceived behavioral control, that is, self-discipline has a greater impact on actual behavior. In contrast, renting behavior is positive behavior that promotes sustainable development, therefore the public pressure is more effective than personally perceived behavior control. As such, to reduce the perceived difficulty of renting for consumers, policymakers should propagate more on rent and encourage the members of the society to rent houses instead of buying. For example, celebrities can advocate for renting and promote its advantages to encourage more people to rent.

Subjective norms (SNs) have a direct positive impact on behavioral intention, which is similar to the research conclusion of Maichum, wherein SNs indicate that the influence of friends/family members resulted in a little thrust concerning the reasons to buy green products for consumers [

91]. Perceived behavioral control has a direct positive impact on behavioral intention, which is contrary to Lin’s research on young consumers’ purchasing intentions for green housing [

92]. We speculate that this phenomenon is caused by the current social norm of housing consumerism in China. Purchasing green housing is also a sustainable behavior. However, housing prices are too high in China and are obviously growing every year [

93]. Buying housing is extremely difficult for young consumers, thus young consumers’ perceived behavioral control has little effect on their purchasing intention for green housing. Renting requires fewer funds, and young consumers’ wages are sufficient for this. Therefore, the perceived behavioral control of young consumers has a positive impact on renting behavior.

Government incentives influence perceived behavioral control (0.41), which was affirmed to have a significant impact on perceived behavioral control. Hence, the government should play a vital role in guiding young consumer towards the option of renting. This conclusion is consistent with the finding in extant studies. Diyana validated that government incentives have the strongest influence on the development of green buildings [

72]. According to traditional Chinese concepts, most Chinese people think that there is room for having a home and that renting lacks a sense of belonging [

26]. In addition, the policy of ‘the same rights of lease and purchase’ has just been implemented and is still in the initial stage, causing many people to be worried about whether or not renting can be settled and public services be enjoyed through renting. Through the government’s economic incentives, young consumers can get additional financial benefits, which can considerably stimulate their willingness to rent. The conclusion echoes that of James, who found in his surveys that the satisfaction of the tenants who have obtained government economic subsidies is much higher than that of unsubsidized tenants. The findings validate the view that economic subsidies can stimulate demand growth [

94]. Therefore, the government should formulate a variety of economic policies to encourage citizens to rent housing. These incentives should aim to improve the rental market and achieve sustainable development of the real estate market. In addition, different incentive policies have been reported to have different effects on renting intentions. Governmental incentives include three observed variables, namely, economic subsidies, tax incentives and preferential loan policies. The value of standardized factor loading indicates that preferential loan policy (0.94) had the most significant influence, followed by economic subsidies (0.87) and tax incentives (0.80). We deduce that this situation is because provident fund loans can be used for purchasing a home but not for rent, and the provident fund loan interest rate is 0.65% lower than the commercial loan, which saves large amounts of loan interest. Therefore, young consumers easily accept the preferential loan policy. At present, people cannot gain high returns through economic subsidies and tax incentives from public housing. Preferential loan policies are more attractive than economic subsidies and tax incentives. In the process of promoting renting, the government should cooperate with private enterprises or other financial institutions to activate the rental market. At present, major developers such as Vanke and Longfor are actively expanding their leasing businesses. Public-private partnerships can solve limited financial support for the government and a number of audiences prefer to rent through active guidance from government departments, which can achieve a win-win situation.

7. Conclusions and Implications

This study mainly explored the influencing factors of young consumers’ intentions and behaviors for renting in the Chinese housing market context. The findings have proven the predictive power of the proposed theoretical framework. This study has the following theoretical contributions: Firstly, an extended TPB is integrated with theories of perceived usefulness, perceived usability and government incentives. The proposed model and measurement scales were also confirmed to be suitable for the study. Secondly, seven different hypotheses are proposed in accordance with the theoretical model. Lastly, the differences of determinants in terms of intention and behavior of renting are compared. The potential methodology contributions of this study are as follows. Initially, a confirmatory factor analysis is employed to assess reliability and validity. Next, the SEM is used to testify different hypotheses. Lastly, correlation analysis is performed on the basis of the data analysis.

In the context of rapid economic development in China, the demand for rental housing is growing because of its positive impact on economic transformation and social sustainability. The present research has proved the usefulness and applicability of TPB in determining the consumers’ intention as well as behavior towards renting housing in the Chinese context. The empirical analysis revealed that young generation’s intentions and behavior to rent housing can be predicted directly or indirectly by attitude towards behavior, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control. Perceived usefulness and perceived usability had most influence on the intention and behavior of housing renting among young generation as antecedent variables of ATT, followed by SN, and lastly PBC. Government incentives have a significant positive impact on PBC as antecedent variables and indirectly affect behavioral intentions through PBC. Finally, behavioral intention has a significant positive influence on actual behavior, indicating that young Chinese consumers with rental ideas can actively choose to rent.

To facilitate the sustainable development of a city and enterprise transformation, we present management suggestions from the perspectives of the government and enterprises based on the research findings.

(1) Perspective of the government: First, the government should expand the scope of public services. At present, the most important factor for lessees is the school district resources. The existing educational resources cannot meet the demands of society. Thus, the government should carry out reforms from the supply side by building more schools and distributing educational resources in a balanced manner. Second, the real estate tax should be adjusted. In the link between housing construction and transaction, the tax should be simplified to reduce the tax burden. In addition, the government should levy real estate tax on individual housing and reduce the comprehensive tax burden of the lessor. Finally, the government should explore the use of the PPP model to expand the supply of rental housing. In PPP, private enterprise is responsible for the construction and operation of leased apartments while the government provides land and tax benefits to the private enterprise while offering consumers certain economic benefits to entice them to lease apartments.

(2) Perspective of the enterprises: Improving the quality and safety of rental housing is essential. Enterprises should also provide living and entertainment facilities for long-term rental apartments to enhance user living standards. To improve ATT and PBC of users, enterprises should establish a convenient leasing platform that combines service evaluation and the credit system and should introduce and use financial products and financial services to increase the speed and breadth of expansion. State-owned enterprises should establish state-owned leasing groups to provide high-quality housing, adjust the existing rental market and take the lead in expanding the leasing business and in realizing the ideal leasing services.

Future research should also consider a few shortcomings. First, this study uses a questionnaire survey method. The respondents measure their intentions and behaviors towards renting through self-reporting instead of actual behavior. The development of the rental market is a complex system involving many factors, and research from the perspective of the consumer requires further improvement. Furthermore, this paper focuses on the social sustainability of rental housing, ignoring environmental and economic sustainability, and the next study should therefore increase the energy efficiency of rental housing. We could study the sustainable development of rental housing from various aspects. Finally, the data in this study are all collected in the Chinese context. Due to differences in national environments and policies, whether the conclusions of this paper are applicable to other countries remains to be confirmed. In the follow-up study, the measurement questionnaire should be improved, and the sample types should be enriched. By increasing the survey data of the government and enterprises, the influencing factors of rental intention and behavior are explored further.