Research on Sharing Intention Formation Mechanism Based on the Burden of Ownership and Fashion Consciousness

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Q 1: What factors affect the sharing intention of individual service providers?

- Q 2: How can the sharing intention of individual service providers be improved?

2. Resource Sharing and the MOA Framework

2.1. Resource-Sharing Motivation of Individual Service Providers

2.2. Resource-Sharing Ability of Individual Service Providers

2.3. Resource-Sharing Opportunities of Individual Service Providers

3. Boundary Conditions—The Burden of Ownership

4. Boundary Conditions—Fashion Consciousness

5. Method

5.1. Questionnaire Data and Data Collection

5.2. Reliability and Validity

5.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

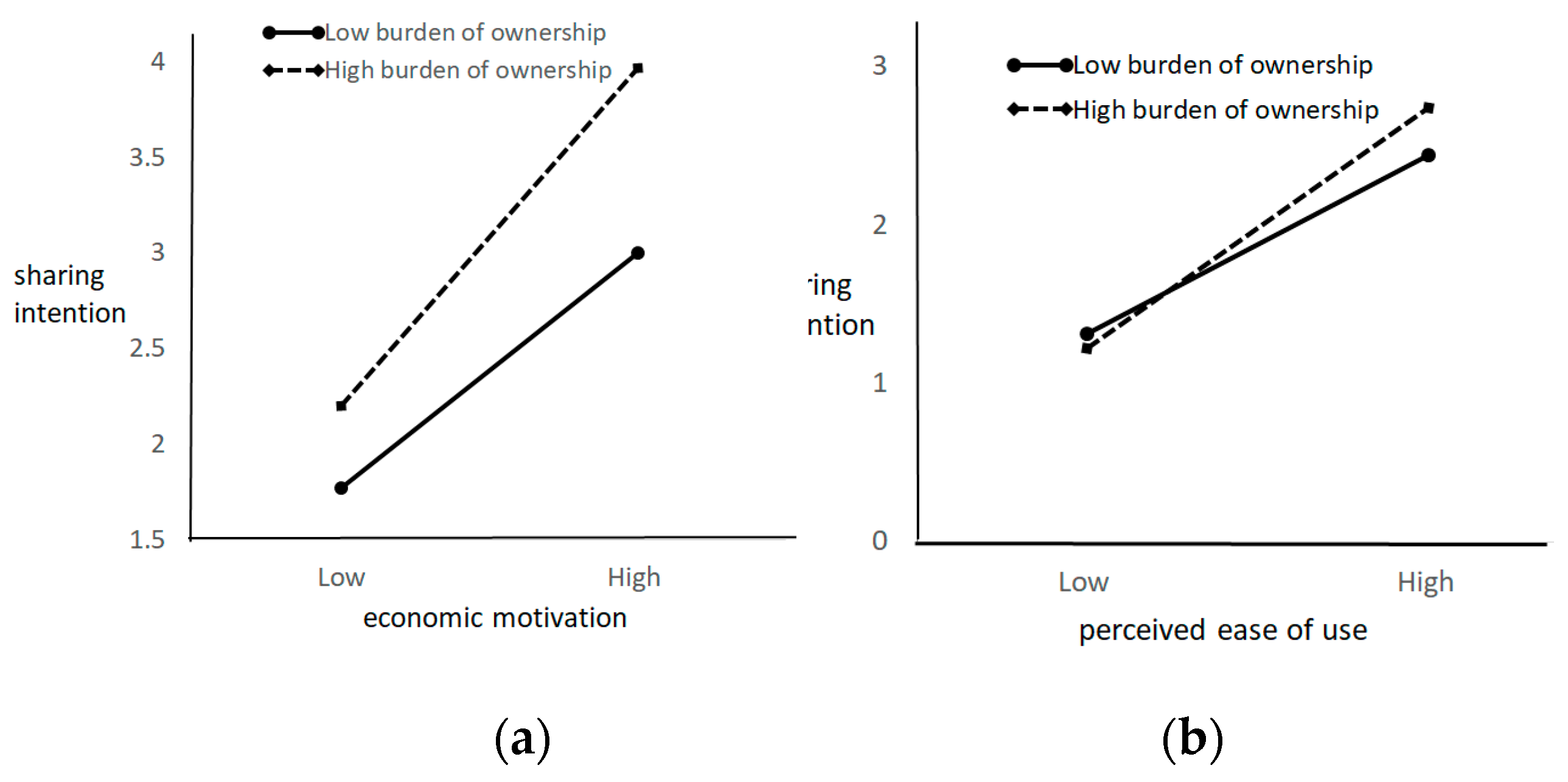

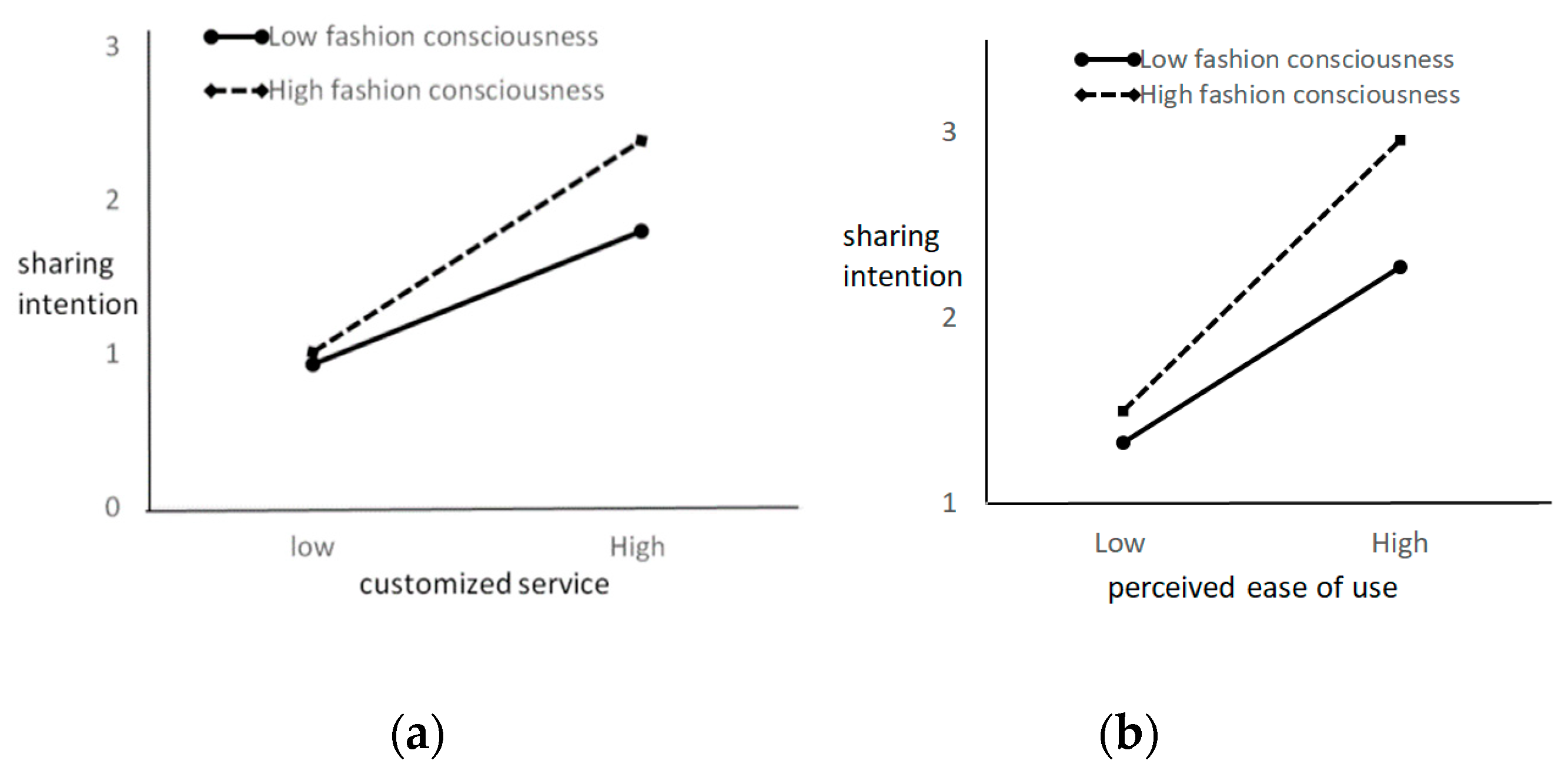

5.4. Regression Analysis

6. Conclusions and Prospects

6.1. Conclusions and Discussion

6.2. Theoretical Contribution and Implications

6.3. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 67–153. [Google Scholar]

- Matzler, K.; Veider, V.; Kathan, W. Adapting to the Sharing Economy. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2015, 56, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lamberton, C.P.; Rose, R.L. When is Ours better than Mine? A Framework for Understanding and Altering Participation in Commercial Sharing Systems. J. Mark. 2012, 6, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. You are What You Can Access: Sharing and Collaborative Consumption Online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G.M. Access-Based Consumption: The Case of Car Sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhlmann, M. Collaborative Consumption: Determinants of Satisfaction and the likelihood of Using a Sharing Economy Option Again. J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 14, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaraboto, D. Selling, Sharing, and Everything In Between: The Hybrid Economies of Collaborative Networks. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 42, 152–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.Q.; Cai, R.L.; Zhu, X.Q. Study of Business Model Innovation for Intelligent Production Sharing. J. China Soft Sci. 2017, 6, 130–139. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C.J. The Sharing Economy: A Pathway to Sustainability or a Nightmarish Form of Neoliberal Capitalism? J. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, B.N.; Burtch, G.; Carnahan, S. Unknowns of the Gig-economy. J. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissinger, A.; Laurell, C.; Öberg, C.; Sandström, C. How Sustainable is the Sharing Economy? On the Sustainability Connotations of Sharing Economy Platforms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, R.; Kozinets, R.V. Lateral Exchange Markets: How Social Platforms Operate in a Networked Economy. J. Mark. 2018, 82, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo, M.; Boyd, C. Mapping Out the Sharing Economy: A Configurational Approach to Sharing Business Modeling. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 125, 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Edbring, E.G.; Lehner, M.; Mont, O. Exploring Consumer Attitudes to Alternative Models of Consumption: Motivations and Barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D.; Smith, S.; Potwarka, L.; Havitz, M. Why Tourists Choose Airbnb: A Motivation-based Segmentation Study. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petriglieri, G.; Ashford, S.; Wrzesniewski, A. Thriving in the Gig Economy. J. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2018, 96, 140–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Yang, S.B.; Koo, C. Exploring the Effect of Airbnb Hosts’ Attachment and Psychological Ownership in the Sharing Economy. J. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Trudel, R. The Effect of Recycling Versus Trashing on Consumption: Theory and Experimental Evidence. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Cacho, P.; Molina-Moreno, V.; Corpas-Iglesias, F.A. Family Businesses Transitioning to a Circular Economy Model: The Case of “Mercadona”. Sustainability 2018, 10, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prothero, A.; Dobscha, S.; Freund, J.; Kilbourne, W.; Luchs, M.G.; Ozanne, L.K.; Thogersen, J. Sustainable Consumption: Opportunities for Consumer Research and Public Policy. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B.; Lunardo, R.; Benoit-Moreau, F. Sustainability of the Sharing Economy in Question: When Second-Hand Peer-to-Peer Platforms Stimulate Indulgent Consumption. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 125, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.C.; Tu, L. User Value Co-creation Mechanism in Travel Sharing: A Case Study Based on Uber. J. Manag. World 2017, 8, 154–169. [Google Scholar]

- Gruen, T.W.; Osmonbekov, T.; Czaplewski, A.J. How E-communities Extend the Concept of Exchange in Marketing: An Application of the Motivation, Opportunity, Ability (MOA) Theory. Mark. Theory 2005, 5, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemsen, E.; Roth, A.V.; Balasubramanian, S. How motivation, Opportunity, and Ability Drive Knowledge Sharing: The Constraining-Factor Model. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 426–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, R.; Torben, P.; Nicolai, J.F. Why a central network position isn’t enough: The role of motivation and ability for knowledge sharing in employee networks. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 1277–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, H.E.; Ozanne, L.K.; Ballantine, P.W. Examining Temporary Disposition and Acquisition in Peer-to-Peer Renting. J. Mark. Manag. 2015, 31, 1310–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, E.; Fieseler, C.; Lutz, C. What’s Mine is Yours (for a nominal fee)—Exploring the Spectrum of Utilitarian to Altruistic Motives for Internet-Mediated Sharing. J. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, S.J.; Gleim, M.R.; Perren, R.; Hwang, J. Freedom from Ownership: An Exploration of Access-Based Consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatokun, W.; Nwafor, C.I. The Effect of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation on Knowledge Sharing Intentions of Civil Servants in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Inf. Dev. 2012, 28, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fremstad, A. Sticky Norms, Endogenous Preferences, and Shareable Goods. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2016, 74, 194–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. Factors of Satisfaction and Intention to Use Peer-to-Peer Accommodation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Cohen, B. A Compass for Navigating Sharing Economy Business Models. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 61, 114–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Dutta, S.; Stremersch, S. Customizing Complex Products: When Should the Vendor Take Control? J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 664–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittendorf, C. Collaborative Consumption: The Role of Familiarity and Trust among Millennials. J. Consum. Mark. 2018, 35, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karen, K.M.; Kamyab, S. Millennials in the Workplace: A Communication Perspective on Millennials’ Organizational Relationships and Performance. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, B.; Kietzmann, J. Ride On! Mobility Business Models for the Sharing Economy. J. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, S.; Baker, T.L.; Bolton, R.N.; Gruber, T.; Kandampully, J. A Triadic Framework for Collaborative Consumption (CC): Motives, Activities and Resources & Capabilities of Actors. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 79, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Dellaert, B.G.C.; Stremersch, S. Marketing Mass-Customized Products: Striking a Balance Between Utility and Complexity. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.G.; Lee, J.K.; Fang, E.; Ma, S. Project Customization and the Supplier Revenue–Cost Dilemmas: The Critical Roles of Supplier–Customer Coordination. J. Mark. 2017, 82, 136–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, D.P.; Srinivasan, A. Networks, Platforms, and Strategy: Emerging Views and Next Steps. J. Strat. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantiou, I.; Marton, A.; Tuunainen, V.K. Four Models of Sharing Economy Platforms. J. MIS Q. Exec. 2017, 16, 231–251. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, N.D.; Shaheen, S.A. Ridesharing in North America: Past, Present, and Future. J. Trans. Rev. 2012, 32, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, S.; Wittkowski, K. The Burdens of Ownership: Reasons for Preferring Renting. J. Manag. Serv. Q. 2010, 20, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Dholakia, U.M.; Chen, X.; Algesheimer, R. Does Online Community Participation Foster Risky Financial Behavior? J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.C.; Goodstein, R.C. The Moderating Effect of Perceived Risk on Consumers’ Evaluations of Product Incongruity: Preference for the Norm. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, G.R.; Staelin, R. A Model of Perceived Risk and Intended Risk-handling Activity. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefers, T.; Lawson, S.; Kukar-Kinney, M. How the Burdens of Ownership Promote Consumer Usage of Access-Based Services. J. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinhee, N.; Hamlin, R.; Hae, J.G.; Ji, H.K.; Jiyoung, K.; Pimpawan, K.; Starr, C.; Richards, L. The Fashion-Conscious Behaviors of Mature Female Consumers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hyun-Joo, L.; Heejin, L.; Jolly, L.D.; Jieun, L. Consumer Lifestyles and Adoption of High-Technology Products: A Case of South Korea. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2009, 21, 153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Kucukemiroglu, O. Market Segmentation by Using Consumer lifestyle Dimensions and Ethnocentrism. Eur. J. Mark. 1999, 33, 470–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, J.O. The Identity of Women’s Clothing Fashion Opinion Leaders. J. Mark. Res. 1970, 7, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cass, A.; McEwen, H. Exploring Consumer Status and Conspicuous Consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2004, 4, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, C.; Sands, S.; Brace-Govan, J. The Role of Fashionability in Second-Hand Shopping Motivations. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967; pp. 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Peng, D.Y.; Xie, F. A Study on the Effects of TAM/TPB-based Perceived Risk Cognition on User’s Trust and Behavior Taking Yu’ ebao, a value-added Payment Product, as an Example. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 28, 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1991; pp. 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- De Brito, M.P.; Carbone, V.; Blanquart, C.M. Towards a Sustainable Fashion Retail Supply Chain in Europe: Organisation and performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 114, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshleifer, D.; Teoh, S.H. Limited Attention, Information Disclosure, and Financial Reporting. J. Account. Econ. 2003, 36, 337–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Reischauer, G. Capturing the Dynamics of the Sharing Economy: Institutional Research on the Plural Forms and Practices of Sharing Economy Organizations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 125, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The Sharing Economy: Why People Participate in Collaborative Consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct and Item Description | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|

| economic motive [27] (α = 0.852, CR = 0.876, AVE = 0.586) | |

| 1. I share because it pays well 2. Sharing helps me pay my bills | 0.774 0.801 |

| 3. Earning extra money is an important factor when sharing | 0.682 |

| 4. Sharing is a good way to supplement my income | 0.778 |

| 5. Sharing allows me to make money from something I own | 0.788 |

| customized service [39] (α = 0.821, CR = 0.851, AVE = 0.656) | |

| 1. I could provide customers with the products/services they need. | 0.771 |

| 2. I extensively customized a range of products/services to meet unique customer needs | 0.864 |

| 3. Products/services provided to this customer has a lot of features that are not available in the standard version | 0.792 |

| perceived ease of use [55] (α = 0.812, CR = 0.852, AVE = 0.658) | |

| 1. The usage steps and operation rules of xx platform are clear and easy to understand | 0.826 |

| 2. It is difficult for me to learn how to use xx platform | 0.844 |

| 3. All in all, I can easily put my underutilized resources on the XX platform | 0.761 |

| the burden of ownership [43] (α = 0.912, CR = 0.922, AVE = 0.748) | |

| 1. underutilized resources may face alteration and or obsolescence risks | 0.889 |

| 2. underutilized resources may face maintenance and repair risks | 0.889 |

| 3. I may have to bear the full cost of goods for which I have only infrequent use | 0.867 |

| 4. The goods (which have passed the guaranteed return period) would be reused after a while, unfortunately, it may be an incorrect selection | 0.811 |

| Fashion Consciousness [50] (α = 0.927, CR = 0.940, AVE = 0.776) | |

| 1. I always try new products or services before my friends, such as sharing underutilized resources with others | 0.877 |

| 2. When choices have to be made, I tend to choose products/services that have a unique style rather than a common one | 0.904 |

| 3. I usually try the latest products and services, such as registering as an Uber owner | 0.905 |

| 4. I often talk to friends about the latest products and services, such as the sharing economy. | 0.883 |

| sharing intention [27] (α = 0.907, CR = 0.903, AVE = 0.650) | |

| 1. If the circumstances allow it, I will also share in the future | 0.787 |

| 2. I may share with others in the future | 0.828 |

| 3. It is likely that I keep sharing in the future | 0.809 |

| 4. I intend to share with others in the future as well | 0.824 |

| 5. I will try to share in the future | 0.783 |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| economic motive | 5.424 | 0.760 | 1.000 | ||||

| customized service | 5.302 | 0.817 | 0.390 ** | 1.000 | |||

| perceived ease of use | 5.506 | 0.801 | 0.270 ** | 0.315 ** | 1.000 | ||

| the burden of ownership | 5.403 | 1.068 | 0.268 ** | 0.222 ** | 0.214 ** | 1.000 | |

| fashion consciousness | 4.562 | 1.37 | 0.208 ** | 0.202 ** | 0.111 | 0.118 * | 1.000 |

| sharing intention | 5.539 | 0.723 | 0.339 ** | 0.369 ** | 0.406 ** | 0.316 ** | 0.269 ** |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Variables | ||||

| Gender | 0.002 | 0.019 | 0.001 | −0.029 |

| Age | −0.971 | −1.042 | −0.982 | −1.502 |

| Monthly income | 0.183 | 0.098 | 0.077 | 0.043 |

| Direct effects | ||||

| Economic motive | 0.107 * | 0.083 | 0.117 * | |

| Customized service | 0.142 ** | 0.149 ** | 0.154 ** | |

| Perceived ease of use | 0.230 *** | 0.209 *** | 0.207 *** | |

| the burden of ownership | 0.154 *** | 0.170 *** | 0.167 *** | |

| Fashion consciousness | 0.086 * | 0.090 ** | 0.104 *** | |

| interaction effects | ||||

| Economic motive x the burden of ownership | 0.167 *** | |||

| Customized service x the burden of ownership | −0.161 ** | |||

| Perceived ease of use x the burden of ownership | 0.114 * | |||

| Economic motive x Fashion consciousness | −0.158 *** | |||

| Customized service x Fashion consciousness | 0.117 *** | |||

| Perceived ease of use x Fashion consciousness | 0.119 *** | |||

| R2 | 0.005 | 0.329 | 0.379 | 0.407 |

| Adjusted R2 | −0.005 | 0.311 | 0.356 | 0.384 |

| F | 0.493 | 28.161 *** | 7.739 *** | 12.546 *** |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Shi, P. Research on Sharing Intention Formation Mechanism Based on the Burden of Ownership and Fashion Consciousness. Sustainability 2019, 11, 992. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040992

Zhang G, Wang L, Shi P. Research on Sharing Intention Formation Mechanism Based on the Burden of Ownership and Fashion Consciousness. Sustainability. 2019; 11(4):992. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040992

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Guangling, Liying Wang, and Pengfei Shi. 2019. "Research on Sharing Intention Formation Mechanism Based on the Burden of Ownership and Fashion Consciousness" Sustainability 11, no. 4: 992. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040992

APA StyleZhang, G., Wang, L., & Shi, P. (2019). Research on Sharing Intention Formation Mechanism Based on the Burden of Ownership and Fashion Consciousness. Sustainability, 11(4), 992. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040992