Consequences of Cultural Leadership Styles for Social Entrepreneurship: A Theoretical Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

“the nature of the influencing process – and its resultant outcomes – that occurs between a leader and followers and how this influencing process is explained by the leader’s dispositional characteristics and behaviors, follower perceptions and attributions of the leader, and the context in which the influencing process occurs [italics added].”[41] (p. 5)

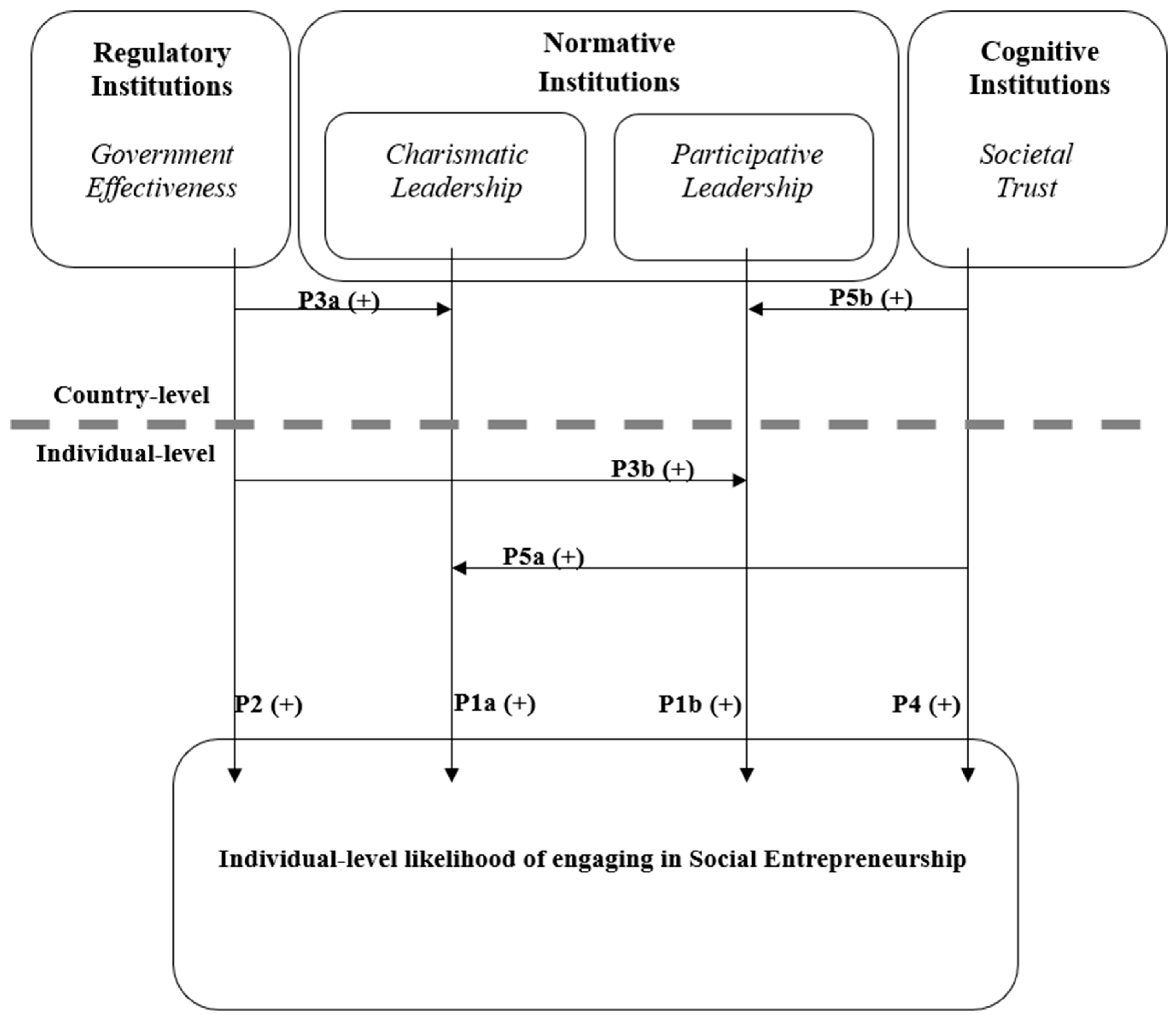

2. Conceptual Framework and Proposition Development

2.1. Social Entrepreneurship

2.2. National-level Institutions

2.3. Leadership, Culturally Endorsed Implicit Leadership, and Social Entrepreneurship

2.4. Normative Institutional Context: Charismatic and Participative CLTs

2.5. Regulatory Institutional Context: Government Effectiveness

2.6. CLTs, Governmental Effectiveness, and Social Entrepreneurship

2.7. Cognitive Institutional Context: Societal Trust

2.8. CLTs, Societal Trust, and Social Entrepreneurship

3. Discussion

3.1. Contributions

3.2. Implications for Practice and Future Research

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mulgan, G. The process of social innovation. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2006, 1, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.; Lee, H.; Ghobadian, A.; O’Regan, N.; James, P. Social innovation and social entrepreneurship: A systematic review. Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 40, 428–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chell, E. Social enterprise and entrepreneurship: Towards a convergent theory of the entrepreneurial process. Int. Small Bus. J. 2007, 25, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chell, E.; Nicolopoulou, K.; Karatas-Özkan, M. Social entrepreneurship and enterprise: International and innovation perspectives. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J.G.; Anderson, B.B. Framing a theory of social entrepreneurship: Building on two schools of practice and thought. In Research on Social Entrepreneurship: Understanding and Contributing to an Emerging Field; Mosher-Williams, R., Ed.; ARNOVA Occasional Paper Series 1(3); ARNOVA: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2006; pp. 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- Estrin, S.; Mickiewicz, T.; Stephan, U. Entrepreneurship, Social Capital, and Institutions: Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship Across Nations. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.; Lee, J.; Chung, Y. Value Creation Mechanism of Social Enterprises in Manufacturing Industry: Empirical Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, R.; Schulz, S.; Richter, L.; Schreck, M. Following Gandhi: Social Entrepreneurship as a NonViolent Way of Communicating Sustainability Challenges. Sustainability 2014, 6, 1018–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perényi, Á.; Losoncz, M. A Systematic Review of International Entrepreneurship Special Issue Articles. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.D.; Swanson, L.A. Linking social entrepreneurship and sustainability. J. Soc. Entrep. 2014, 5, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.M.S.; Sousa, C.A.A. Is Psychological Value a Missing Building Block in Societal Sustainability? Sustainability 2018, 10, 4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, S.; Janssen, F. The Multiple Faces of Social Entrepreneurship: A Review of Definitional Issues based on Geographical and Thematic Criteria. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2011, 23, 373–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Drencheva, A. The person in social entrepreneurship: A systematic review of research on the social entrepreneurial personality. In The Wiley Handbook of Entrepreneurship; Ahmetoglu, G., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Klinger, B., Karcisky, T., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 205–229. [Google Scholar]

- Rusu, V.D.; Roman, A. Entrepreneurial Activity in the EU: An Empirical Evaluation of its Determinants. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B.; Kujinga, L. The institutional environment and social entrepreneurship intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 638–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G.; Ahlstrom, D. An Institutional View of China’s Venture Capital Industry: Explaining the Differences Between China and the West. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, A. The Social and Institutional Context of Entrepreneurship. In Crossroads of Entrepreneurship; Corbetta, G., Huse, M., Ravasi, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 58–74. [Google Scholar]

- Heilbrunn, S.; Itzkovitch, Y.; Weinberg, C. Perceived feasibility and desirability of entrepreneurship in institutional contexts in transition. Entrep. Res. J. 2017, 7, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, E.; Pathak, S. Informal institutions and international entrepreneurship. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.; Muralidharan, E. Informal Institutions and Their Comparative Influences on Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: The Role of In-Group Collectivism and Interpersonal Trust. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousafzai, S.Y.; Saeed, S.; Muffatto, M. Institutional theory and contextual embeddedness of women’s entrepreneurial leadership: Evidence from 92 countries. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.; Muralidharan, E. Economic Inequality and Social Entrepreneurship. Bus. Soc. 2018, 57, 1150–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F.; Smallbone, D. Institutional perspectives on entrepreneurial behaviour in challenging environments. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar Jahanshahi, A.; Brem, A.; Shahabinezhad, M. Does Thinking Style Make a Difference in Environmental Perception and Orientation? Evidence from Entrepreneurs in Post-Sanction Iran. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, E.; Pathak, S. Sustainability, Transformational Leadership, and Social Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2018, 10, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newth, J. Social enterprise innovation in context: Stakeholder influence through contestation. Entrep. Res. J. 2016, 6, 369–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newth, J.; Woods, C. Resistance to social entrepreneurship: How context shapes innovation. J. Soc. Entrep. 2014, 5, 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoutre, J.; Justo, R.; Terjesen, S.; Bosma, N. Designing a Global Standardized Methodology for measuring Social Entrepreneurship Activity: The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Social Entrepreneurship Study. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, B. The Prevalence and Determinants of Social Entrepreneurship at the Macro Level. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Uhlaner, L.M.; Stride, C. Institutions and social entrepreneurship: The role of institutional voids, institutional support, and institutional configurations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 46, 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.C.; Moss, T.W.; Lumpkin, G.T. Research in social entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future opportunities. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2009, 3, 161–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felício, J.A.; Martins Gonçalves, H.; da Conceição Gonçalves, V. Social value and organizational performance in non-profit social organizations: Social entrepreneurship, leadership, and socioeconomic context effects. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2139–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.P. Entrepreneurship and leadership: Common trends and common threads. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2003, 13, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogliser, C.C.; Brigham, K.H. The intersection of leadership and entrepreneurship: Mutual lessons to be learned. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 771–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; Mort, G.S. Investigating social entrepreneurship: A multidimensional model. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, G.N. Social entrepreneurial leadership. Career Dev. Int. 1999, 4, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman-Storen, R. Leadership in sustainability: Creating an interface between creativity and leadership theory in dealing with “Wicked Problems”. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5955–5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Pathak, S. Beyond cultural values? Cultural leadership ideals and entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liu, H.; Chin, T.; Hu, D. The Continuous Mediating Effects of GHRM on Employees’ Green Passion via Transformational Leadership and Green Creativity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, D.; Lyu, C.; Zhang, H. Does Seeing “Mind Acts Upon Mind” Affect Green Psychological Climate and Green Product Development Performance? The Role of Matching Between Green Transformational Leadership and Individual Green Values. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J.; Gianciolo, A.T.; Sternberg, R.J. Leadership: Past, present, and future. In The Nature of Leadership; Antonakis, J., Gianciolo, A.T., Sternberg, R.J., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakis, J.; Autio, E. Entrepreneurship and leadership. In The Psychology of Entrepreneurship; Baum, J., Frese, M., Baron, R.A., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 189–208. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaventura, L.; Caserta, M. The social dimension of entrepreneurship: The role of regional social effects. Entrep. Res. J. 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Transformational Leadership: Industrial, Military, and Educational Impact; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- House, R.J.; Dorfman, P.; Javidan, M.; Hanges, P.J.; Sully De Luque, M. Strategic Leadership Across Cultures: GLOBE Study of CEO Leadership Behaviour and Effectiveness in 24 Countries; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Crossan, M.; Vera, D.; Nanjad, L. Transcendent leadership: Strategic leadership in dynamic environments. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lado-Sestayo, R.; Neira-Gómez, I.; Chasco-Yrigoyen, C. Entrepreneurship at regional level: Temporary and neighborhood effects. Entrep. Res. J. 2017, 7, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levie, J.; Autio, E. Regulatory burden, rule of law, and entry of strategic entrepreneurs: An international panel study. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1392–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puffer, S.M.; McCarthy, D.J.; Boisot, M. Entrepreneurship in Russia and China: The Impact of Formal Institutional Voids. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutional theory: Contributing to a theoretical research program. In Great Minds in Management: The Process of Theory Development; Smith, K.G., Hitt, M.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Understanding the Process of Economic Change; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei-Skillern, J. Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different or Both? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noruzi, M.R.; Westover, J.R.; Rahimi, G.R. An exploration of social entrepreneurship in the entrepreneurship Era. Asian Soc. Sci. 2010, 6, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Conceptions of social enterprise and social entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: Convergences and divergences. J. Soc. Entrep. 2010, 1, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, S.; Hartog, C.; Hoogendoorn, B. A quantitative comparison of social and commercial entrepreneurship: Toward a more nuanced understanding of social entrepreneurship organizations in context. J. Soc. Entrep. 2013, 4, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierhoff, H.W. Prosocial Behaviour; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S.E.; Gedajlovic, E.; Neubaum, D.O.; Shulman, J.M. A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I. Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, O.M.; Kansikas, J. Opportunity recognition in social entrepreneurship: A thematic meta analysis. J. Entrep. 2012, 21, 25–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, S.A.; De Clercq, D. Entrepreneurs’ individual-level resources and social value creation goals: The moderating role of cultural context. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrin, S.; Mickiewicz, T.; Stephan, U. Human capital in social and commercial entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachlami, H.; Yazdanfar, D.; Öhman, P. Regional demand and supply factors of social entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 714–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gras, D.; Lumpkin, G.T. Strategic Foci in Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: A Comparative Analysis. J. Soc. Entrep. 2012, 3, 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Domenico, M.; Tracey, P.; Haugh, H. The Dialectic of Social Exchange: Theorizing Corporate-social Enterprise Collaboration. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 887–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sud, M.; VanSandt, C.V.; Baugous, A.M. Social Entrepreneurs: The Role of Institution. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A. Social Entrepreneurship: The Emerging Landscape. In Financial Times Handbook of Management, 3rd ed.; FT Prentice-Hall: Harlow, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.; Anheier, H. The Sociology of Nonprofit Organizations and Sectors. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1990, 16, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.W.; DiMaggio, P.J. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dacin, M.T.; Dacin, P.A.; Tracey, P. Social entrepreneurship: A critique and future directions. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Wright, M. Entrepreneurship’s next act. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2011, 25, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Toledano, N.; Sorian, D.R. Analyzing social entrepreneurship from an institutional perspective: Evidence from Spain. J. Soc. Entrep. 2010, 1, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, F.M. A positive theory of social entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlaner, L.M.; Thurik, R. Postmaterialism influencing total entrepreneurial activity across nations. J. Evol. Econ. 2007, 17, 2–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, C.E.; Holtschlag, C. Postmaterialist values and entrepreneurship: A multilevel approach. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2013, 19, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidan, M.; House, R.J.; Dorfman, P.; Hanges, P.J.; Sully De Luque, M. Conceptualizing and measuring cultures and their consequences: A comparative review of GLOBE’s and Hofstede’s approaches. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, K.; Kostova, T. Organizational coping with institutional upheaval in transition economies. J. World Bus. 2003, 38, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D.; Gundry, L.K.; Kickul, J.R. The social political, economic and cultural determinants of social entrepreneurship activity. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2013, 20, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelos, C.; Mair, J.; Battilana, J.; Dacin, M. The embeddedness of social entrepreneurship: Understanding variation across local communities. Res. Sociol. Organ. 2011, 33, 333–363. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, B. Social entrepreneurship in an emerging economy: A focus on the institutional environment and SESE. Manag. Glob. Transit. Int. Res. J. 2013, 11, 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, U.; Uhlaner, L.M. Performance-based vs. socially supportive culture: A cross-national study of descriptive norms and entrepreneurship. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 1347–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G.D.; Ahlstrom, D.; Li, H.-L. Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: Where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenitz, L.W.; Gomez, C.; Spencer, J.W. Country Institutional Profiles: Unlocking Entrepreneurial Phenomena. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 994–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez, M.E.; Richardson, J. Institutional determinants of macro–level entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 1149–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, T. Country Institutional Profile: Concept and Measurement; Best Paper Proceedings of the Academy of Management; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Sine, W.D.; David, R.J. Institutions and Entrepreneurship; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: West Yorkshire, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, B. Social entrepreneurship in South Africa: Delineating the construct with associated skills. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2008, 14, 346–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Riggio, R.E.; Lowe, K.B.; Carsten, M.K. Followership theory: A review and research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairhurst, G.T.; Uhl-Bien, M. Organizational discourse analysis (ODA): Examining leadership as a relational process. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 1043–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D.V.; Fleenor, J.W.; Atwater, L.E.; Sturm, R.E.; McKee, R.A. Advances in leader and leadership development: A review of 25 years of research and theory. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, J.E.; Lord, R.G.; Gardner, W.L.; Meuser, J.D.; Liden, R.D.; Hu, J. Leadership theory and research in the new millennium: Current theoretical trends and changing perspectives. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 36–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionne, S.D.; Gupta, A.; Sotak, K.L.; Shirreffs, K.A.; Serban, A.; Hao, C.; Kim, D.H.; Yammarino, F.J. A 25-year perspective on levels of analysis in leadership research. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 6–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epitropaki, O.; Martin, R. Implicit leadership theories in applied settings: Factor structure, generalizability, and stability over time. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schyns, B.; Meindl, J.R. An overview of implicit leader- ship theories and their application in organization practice. In The Leadership Horizon Series: Implicit Leadership Theories—Essays and Explorations; Schyns, B., Meindl, J.R., Eds.; Informati: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2005; pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, R.G. An information processing approach to social perceptions, leadership and behavioral measurement in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 1985, 7, 87–128. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, R.G.; Foti, R.J.; De Vader, C.L. A test of leadership categorization theory: Internal structure, information processing, and leadership perceptions. Organ. Behav. Hum. Performance 1984, 34, 343–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R.G.; Maher, K.J. Leadership and Information Processing: Linking Perceptions and Performance; Unwin Hyman: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Epitropaki, O.; Sy, T.; Martin, R.; Tram-Quon, S.; Topakas, A. Implicit Leadership and Followership Theories “in the wild”: Taking stock of information-processing approaches to leadership and followership in organizational settings. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 858–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Javidan, M.; Dorfman, P.W.; Gupta, V. Culture, Leadership and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; House, R.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Ruiz-Quintanilla, S.A.; Dorfman, P.W. Culture specific and cross-culturally generalizable implicit leadership theories. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 219–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, R.L.; Walls, J.; Frese, M. Cross-cultural entrepreneurship: The case of China. In The Psychology of Entrepreneurship; Baum, J.R., Frese, M., Baron, R., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 265–286. [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman, P.; Javidan, M.; Hanges, P.; Dastmalchian, A.; House, R. GLOBE: A twenty-year journey into the intriguing world of culture and leadership. J. World Bus. 2012, 47, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Jones, F.F. Entrepreneurship in established organizations: The case of the public sector. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1999, 24, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.B. Managing innovation: Controlled chaos. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1985, 63, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Muralidharan, E.; Pathak, S. Culturally Endorsed Leadership Styles and Entrepreneurial Behaviors in Asia. In The Palgrave Handbook of Leadership in Transforming Asia; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 333–348. [Google Scholar]

- Hanges, P.J.; Dickson, M.W. The development and validation of the GLOBE culture and leadership scales. In Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies; House, R.J., Hanges, P.J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P.W., Gupta, V., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbert, S.A.; Hogg, G.; Quinn, T. Consumer response to social entrepreneurship: The case of the Big Issue in Scotland. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2001, 7, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermerhorn, J.; Hunt, J.; Osborn, R. Organizational Behaviour, 9th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nurmi, R.; Darling, J. International Management Leadership: The Primary Competitive Advantage; International Business Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dees, J. Enterprising nonprofits. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1988, 76, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Frese, M.; Gielnik, M.M. The psychology of entrepreneurship. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E.; Carter, S. Social entrepreneurship: Theoretical antecedents and empirical analysis of entrepreneurial processes and outcomes. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2007, 14, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Sorenson, R.L. Collective Entrepreneurship in Family Firms: The Influence of Leader Attitudes and Behaviours. N. Engl. J. Entrep. 2003, 6, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, V.H.; Yetton, P.W. Leadership and Decision Making; University of Pittsburg Press: Pittsburg, PA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J. An empirical examination of the interactive effects of goal orientation, participative leadership and task conflict on innovation in small business. J. Dev. Entrep. 2011, 16, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.; Weingart, L.R. Task versus relationship conflict, team performance and team member satisfaction: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, M. Challenging tensions: Critical, theoretical and empirical perspectives on social enterprise. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2008, 14, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastruzzi, M. The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. Hague J. Rule Law 2011, 3, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.N.; Danis, W.M. Country institutional context, social networks, and new venture internationalization speed. Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyskens, M.; Carsrud, A.L.; Cardozo, R.N. The symbiosis of entities in the social engagement network: The role of social ventures. Entrep. Reg. Dev 2010, 22, 425–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G.D.; Fried, V.H.; Manigart, S. Institutional influences on the worldwide expansion of venture capital. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 737–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcock, M.; Narayan, D. Social capital: Implications for development theory, Research and policy. World Bank Res. Obs. 2000, 15, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafo, A.; Sagiv, L. Values and work environment: Mapping 32 occupations. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2004, 19, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noseleit, F. The entrepreneurial culture: Guiding principles of the self-employed. In Entrepreneurship and Culture; Freytag, A., Thurik, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Roccas, S.; Sagiv, L.; Schwartz, S.H.; Knafo, A. The Big Five personality factors and personal values. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. A theory of cultural value orientations: Explication and applications. Comp. Sociol. 2006, 5, 137–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, M.; Traunnlüller, R. Spheres of trust: An empirical analysis of the foundations of particularised and generalised trust. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2009, 48, 782–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhey, J.; Newton, K.; Welzel, C. How general is trust in “most people”? Solving the radius of trust problem. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 76, 786–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. Trust; Penguin: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Banfield, E. The Moral Basis of Backward Society; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, R. Trust; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, R.M. Trust and Distrust in Organizations: Emerging Perspectives, Enduring Questions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1999, 50, 569–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Cummings, L.L.; Chervany, N.L. Initial Trust Formation in New Organizational Relationships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muethel, M.; Bond, M.H. National Context and Individual Employees’ Trust of the Out-group: The Role of Societal Trust. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2013, 44, 312–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetto, Y.; Farr-Wharton, T. The Moderating Role of Trust in SME Owner/Managers’ Decision-Making about Collaboration. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2007, 45, 362–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H. Entrepreneurial Strategies in New Organizational Populations. In Entrepreneurship: The Social Science View; Swedberg, R., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Morales, F.X.; Martínez-Fernández, M.T. Social networks: Effects of social capital on firm innovation. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2010, 48, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S.D.; Dew, N.; Velamuri, S.R.; Venkataraman, S. Three views of entrepreneurial opportunity. In International Handbook of Entrepreneurship; Audretsch, D., Acs, Z., Eds.; Kluwer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, J.H.; Chu, W.J. The role of trustworthiness in reducing transaction costs and improving performance: Empirical evidence from the United States, Japan, and Korea. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Moss, T.W.; Gras, D.M.; Kato, S.; Amezcua, A.S. Entrepreneurial Processes in Social Contexts: How are they different, if at all? Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 761–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.-W.; Arenius, P. Nations of entrepreneurs: A social capital perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayob, A.H. Diversity, Trust and Social Entrepreneurship. J. Soc. Entrep. 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. Leadership in Organizations, 6th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Tsai, C.H.; Tsai, F.S.; Huang, W.; de la Cruz, S. Antecedent and Consequences of Psychological Capital of Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarniawska-Joerges, B.; Wolff, R. Leaders, managers, entrepreneurs on and off the organisational stage. Organization Studies 1991, 12, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, C.M.; McDougall, P.P.; Covin, J.G. Governance and strategic leadership in entrepreneurial firms. J. Manag. 2002, 28, 387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D.V. The nature of leadership development. In The Nature of Leadership, 2nd ed.; Day, D.V., Antonakis, J., Eds.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 108–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hayton, J.C.; Cacciotti, G. Is there an entrepreneurial culture? A review of empirical research. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2013, 25, 708–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.C.; Payne, G.T.; Ketchen, D.J. Research on organizational configurations: Past accomplishments and future challenges. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 1053–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Pathak, S.; Wennberg, K. Consequences of cultural practices for entrepreneurial behaviours. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2013, 44, 334–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.; Muralidharan, E. GLOBE Leadership Dimensions: Implications for Cross-Country Entrepreneurship Research. Acad. Int. Bus. Insights 2018, 18, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Schyns, B.; Kiefer, T.; Kerschreiter, R.; Tymon, A. Teaching implicit leadership theories to develop leaders and leadership: How and why it can make a difference. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2011, 10, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Avery, G. Sustainable leadership practices driving financial performance: Empirical evidence from Thai SMEs. Sustainability 2016, 8, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayton, J.C.; George, G.; Zahra, S.A. National culture and entrepreneurship: A review of behavioural research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 26, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, H.; Stephan, U. Moving on from nascent entrepreneurship: Measuring cross-national differences in the transition to new business ownership. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 41, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muralidharan, E.; Pathak, S. Consequences of Cultural Leadership Styles for Social Entrepreneurship: A Theoretical Framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040965

Muralidharan E, Pathak S. Consequences of Cultural Leadership Styles for Social Entrepreneurship: A Theoretical Framework. Sustainability. 2019; 11(4):965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040965

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuralidharan, Etayankara, and Saurav Pathak. 2019. "Consequences of Cultural Leadership Styles for Social Entrepreneurship: A Theoretical Framework" Sustainability 11, no. 4: 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040965

APA StyleMuralidharan, E., & Pathak, S. (2019). Consequences of Cultural Leadership Styles for Social Entrepreneurship: A Theoretical Framework. Sustainability, 11(4), 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040965