Abstract

This paper aims to adapt the social network analysis method to explore the characteristics of 59 cross-border e-commerce policies promulgated by the Chinese government from January 2013 to July 2018. On this basis, the paper quantitatively analyzes the internal structure and dynamic layout characteristics of sustainable cross-border e-commerce policy documents focusing on three dimensions: policy service contents, policy regulatory targets, and policy measures. The results suggest that policies involving service contents lack long-term strategic planning, especially those related to taxation and warehousing. In addition, policies regarding service system construction and demonstration construction follow an upward trend, whereas policies related to international cooperation and risk monitoring are less prevalent. Finally, it is suggested that the government pays attention to the supervision of payments, transactions, and goods in the early stage of development, but began conducting comprehensive supervision over all aspects of the cross-border e-commerce supply chain in 2015. Thus, there has been a relatively mature regulatory system established in China with particular attention to the aspects of quality and safety.

1. Introduction

The rapid development of cross-border e-commerce has become a new momentum driving the growth of China’s foreign trade. What is more, these trends have stimulated the transformation and upgrading of traditional foreign trade modes in multiple dimensions of sustainability [1,2,3]. Therefore, promoting the sustainable development of cross-border e-commerce has become an important goal pursued by policymakers in China [4,5,6,7]. The government’s intervention in cross-border e-commerce development has primarily occurred in the form of cross-border e-commerce policies. Due to structural and macro characteristics of these policies, they are less effective in promoting e-commerce if applied in a single- or one-sided manner [8]. At present, the supervision of cross-border e-commerce involves more than 10 government agencies, such as customs, inspection and quarantine, tax, and industry and commerce offices. This requires developing a collaboration mechanism among the agencies, especially in terms of excessive supervision and negligence [9,10,11,12]. In particular, on 31 August 2018 the Fifth Session of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People’s Congress adopted the “e-commerce law”, proposing the establishment of a supervisory and management system that would address the needs of cross-border e-commerce activities. Indeed, the functioning of the e-commerce system involves economic, social, institutional and environmental issues that need to be addressed in the policy guidelines. Looking at the internal and external environment, sustainability needs to be maintained within the cross-border e-commerce system as well as in interactions with the external agents (e.g., regulatory agencies). As regards dynamics in sustainability, the changes in the markets and institutions require corresponding shifts in regulatory policies. Obviously, establishing and improving the cross-border e-commerce policy system is a prerequisite for a sustainable e-commerce and the economy in general.

Research on China’s cross-border e-commerce policy has mainly focused on the two aspects: First, there have been studies which summarized and compared China’s cross-border e-commerce policies. For example, Lai (2016) argued that the Chinese government has gradually established a policy system adapted to the characteristics of cross-border e-commerce by carding out important node policies of cross-border e-commerce [13]. Gao (2017) focused on the existing cross-border e-commerce legal policies and outlined the evolution of cross-border e-commerce policies in China [14]. Zhang and Yang (2017) summarized cross-border e-commerce policies and analyzed the characteristics of cross-border e-commerce supervision policy [15]. Second, there have been papers addressing the problems existent in the current cross-border e-commerce policies. For example, the taxation of cross-border e-commerce is related to tax evasion and tax reimbursement [16,17,18,19,20]; the costs of customs clearance of cross-border e-commerce tend to be high, yet the efficiency of customs clearance remains low [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]; and cross-border e-commerce foreign exchange administrations face foreign exchange and third-party payment supervision dilemmas [30,31,32]. The inspection and quarantine of cross-border e-commerce suffer from a lack of laws regulating quality supervision, information asymmetry, and discrepancies in product coding information [33,34,35,36].

Since cross-border e-commerce policies directly affect the cross-border e-commerce market, many studies have also considered the impact of policy formulation on cross-border e-commerce enterprises and industries. For example, Kan (2016) has established a government incentive supervision mechanism model to study the effects of government-supported policies on cross-border e-commerce companies [37]. Chen et al. (2017) used data from 203 foreign trade companies to study the impact of cross-border e-commerce policies on corporate performance and e-commerce development [38]. Yang et al. (2018) established a new SIR model for cross-border e-commerce policies based on the Holling-II model, to study the new policies’ influence on e-commerce transactions and its transmission mechanisms [39].

In summary, the literature on cross-border e-commerce policies has mainly focused on theoretical analysis, and only a handful of studies have quantitatively analyzed the design and possible impact of cross-border e-commerce policies. Indeed, the quantitative analysis of the policies can help to reveal the advantages and disadvantages of them and direct the government in formulating and adjusting these policies. The objective of this paper is to identify the major trends in regulation of cross-border e-commerce in China by applying robust quantitative methodology. Therefore, based on the quantitative analysis of cross-border e-commerce policies, this paper establishes a three-dimensional structural framework covering policy service contents, policy regulatory targets, and policy measures, and then depicts the structural characteristics of cross-border e-commerce policies.

2. Literature Review on Research of Policy Structure

In terms of policy structure research, early studies primarily divided innovative policy tools according to different perspectives. For example, Rothwell and Zegveld classified innovation policy tools into supply, demand, and environmental types, drawing on the perspective of policy impact [40]. Lowi classified innovation policy tools into regulatory and non-regulatory ones according to the degree of government involvement [41]. Howlett and Ramesh categorized the policy tools into mandatory tools, voluntary tools, and hybrid tools [42]. McDonnell and Elmore divided innovation policy tools into four categories defined by their different goals: command tools, incentive tools, capacity building tools, and system change tools [43]. Subsequently, the complexity of the policy structure analysis has increased, involving different research fields. For example, Huang et al. established an analytical framework for China’s wind energy policy system by focusing on the dimensions of policy instruments and industrial value chains [44]. Huang et al. quantitatively analyzed the documents on preferential tax policies for high-tech industries from 1987 to 2008 considering four dimensions: year, policy preferential targets, preferential tax types, and preferential measures [45]. Wu and Liu conducted quantitative research and a bibliometric analysis of the policy contents from China’s pension service policy texts taking the dimensions of policy tools and the pension service system into consideration [46].

Obviously, the research based on policy structure is primarily related to different perspectives and policy tools. Although some studies build multidimensional structural frameworks based on the characteristics of specific research fields, the following problems exist: (1) Classification of policy contents is time- and resource-consuming. Generally, to ensure the scientific classification of policy contents, experts must process policy documents individually based on the policy structure. However, policy documents are complicated and this becomes a burdensome task. (2) Classification of policy structure is rather subjective and researchers may rely on different research perspectives that could lead to a lack of scientific rationale. (3) Assigning the same importance to different policy documents may be misleading as the impact of policy strength varies depending on the issuing authority and nature of the documents. (4) The analysis of policy structure is often limited to the number of different policy tools used and, therefore, lacks dynamic analysis. The aforementioned problems can be addressed by combining qualitative and quantitative research tools. The social network analysis method can use UCINET software to quantitatively extract hidden, potential, and unknown internal structures from a large quantity of policy text data to help reduce the cost of processing policy texts [47,48,49,50]. For example, Weishaar, Varone, Zhang, and Yan and Huang applied social network analysis to quantitatively analyze the internal structures of European smoke-free policies, policy initiatives, transformation policies of scientific and technological achievements, and educational policies [51,52,53,54].

This paper uses a social network analysis method based on the above literature to quantitatively analyze the cross-border e-commerce policy structure in China. The research framework presented in the next section addresses the problems enumerated in Section 2. Therefore, we look into the characteristics and structural problems of China’s cross-border e-commerce policies in a more robust manner.

3. Research Framework

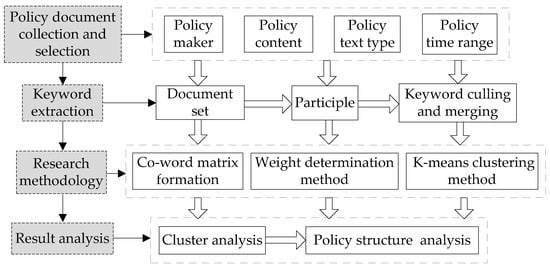

In social network analysis, social systems can be represented by a relationship diagram comprising nodes and connections (flows). In this setting, the nodes represent agents, such as social organizations and groups, and the connections between the nodes represent the relationships among individuals, such as kinship, rights, and affiliation [55,56]. Considering that the keyword network in the cross-border e-commerce policy context can be regarded as a special type of social network, the nodes of the network represent keywords, and the lines among the nodes represent relationships in which keywords appear simultaneously in the policy documents. Therefore, this paper follows the social network analysis approach to quantitatively analyze cross-border e-commerce policy structure (see Figure 1 for the research framework).

Figure 1.

Research framework.

As shown in Figure 1, we started by collecting and selecting the cross-border e-commerce policy documents issued by the central government, and used ROSTCM6 software to extract high-frequency keywords from various policy documents. The latter software was chosen as its Chinese vocabulary is comprehensive, and the operation of word segmentation is flexible and convenient. Our next step was to compile the co-word matrix based on the extracted keywords and used UCINET software for cluster analysis. (UCINET software is suitable for processing medium-sized datasets and allows for statistical analysis [57].) Finally, according to the results of the cluster analysis, we constructed a structural framework of China’s cross-border e-commerce policy and analyzed its dynamic structure. This section further discusses these steps in a more detailed manner.

3.1. Data Collection

This paper considers the cross-border e-commerce policy documents released by the Chinese government. Specifically, 81 cross-border e-commerce policy documents were preliminarily retrieved by screening the relevant lists on the official websites of Peking University Center for Legal Information (pkulaw.cn), the State Council, and the appropriate ministries and commissions. Due to the large number of policy documents on cross-border e-commerce, we filtered policy documents based on the following four principles in order to ensure integrity of the research: (1) the sample is limited to national bodies; (2) the documents must be directly or indirectly related to cross-border e-commerce; (3) the type of the policy document must be opinion, letter, affiche, notice, etc.; and (4) the policy document must have been issued in between January 2013 and July 2018. As the contribution of cross-border e-commerce to the total trade volume exceeded 10% in 2013, the Chinese government began to pay more attention to it and issued a number of policy documents [58,59]. Following the above-mentioned principles, 59 effective policy documents were finally selected for analysis (see Table 1). The distribution of the policy documents in regards to their types is shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

China’s cross-border e-commerce policy documents.

Table 2.

Summary of the policy documents regulating cross-border e-commerce.

The 59 cross-border e-commerce policy documents include opinions, affiches, notices, approvals, letters, notes, points, plans, and others (see Table 2). Among these, the number of opinions, affiches, and notices is the highest, with frequencies of 15, 12, and 10, respectively, accounting for 76% of the policy documents. The numbers of approvals and letters are the next-highest and equal 8 and 5, respectively, while notes, points, plans, and others are the least frequent. This demonstrates that the government focuses on adopting policy documents in the form of opinions, affiches, and notices to manage cross-border e-commerce and related matters, which are mainly considered by lower-level agencies. The major issues addressed in these documents include asymmetry in quality supervision information, customs clearance, and difficulties related to tax refunds. In addition, the government also issues approvals, letters, notes, and points, which are often used by higher authorities to guide subordinates to conduct cross-border e-commerce in pilot areas, among other issues. This shows that the upper and lower levels of the government have formed a linkage in regulation of cross-border e-commerce. In contrast, there are just a few policy documents on in-depth guidance. For instance, the National E-commerce Logistics Development Special Plan (2016–2020) proposes that e-commerce logistics enterprises should strengthen international competitiveness. Still, there is no specific plan for the overall development of cross-border e-commerce and other supply chain links, which causes a lack of clarity in the development direction of the cross-border e-commerce industry in China.

3.2. Keyword Extraction

The extraction of keywords included the following three steps: First, we put 59 cross-border e-commerce policy documents into text files and formed a document set; second, we used ROSTCM6 text mining software to segment the document set and count the frequency of keyword occurrences for the given word segmentation; and third, we excluded duplicate keywords and merged similar ones. Specifically, keywords unrelated to the research topic were excluded. For instance, “expansion”, “acceleration”, “promotion”, and similar keywords were merged; keywords such as “tax refund” and “exemption” were replaced with the keyword “taxation”. Finally, 17 key cross-border e-commerce policy keywords were identified. The frequency of each keyword is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cross-border e-commerce policy keywords.

3.3. Weighted Co-word Matrix

According to the frequency of the keywords related to cross-border e-commerce policy presented above, we counted the number of occurrences of these terms in each policy document considered. Appearance of one or more times in a policy document was recorded as 1. Therefore, matrix containing binary elements, with rows representing keywords and columns representing the documents, was established.

In addition, considering that the higher the level of leadership, the higher the legal effect of the policy it promulgates, we used policy strength to weight the keywords. When setting the weights, we followed the State Council’s Regulations on the Formulation of Regulations classification in regards to regulation intensity by [8] and the actual distribution of cross-border e-commerce policy types in China. Thus, we divided the policy intensity of cross-border e-commerce into levels 1 to 3, based on the policy types when describing policy intensity (see Table 4). The weighted matrix is set as follows:

where are the elements of and are the weights from Table 4.

Table 4.

The weights for cross-border e-commerce policy documents.

Finally, we performed an orthogonal transformation on the weighted matrix to obtain a co-word matrix B.

3.4. K-Means Clustering Method

As K-means clustering is simple and effective, it is one of the most commonly used methods for identifying similar groups of observations. Therefore, this paper adopts K-means clustering to identify clusters of keywords defining the cross-border e-commerce policies. We assumed that the cross-border e-commerce policy keywords should be divided into K categories (different values were tested). Therefore, we first performed the initial division of the elements represented by the rows of into categories and calculated the mean vector (centroid) for each of these categories, , and then allocated each remaining sample to the category closest to its category mean according to the Euclidean distance:

The centroids were re-calculated and assignments made for each iteration until convergence in theory values was achieved.

4. Results

In this section, we first present the classification of the keywords representing the cross-border e-commerce regulation in China. This leads into a content analysis of the major policy directions, which is based on quantitative analysis rather than speculative patterns. Then, the dynamics in the number of manifestations of different policy elements is presented.

4.1. Cluster Analysis

To determine the policy structure in a quantitative manner, we used UCINET software to identify the clusters within the cross-border e-commerce policy keyword network. The four clusters were identified. The results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of the cluster analysis for the cross-border e-commerce policy keyword network.

Cluster 1 comprises the service-oriented issues including customs clearance, logistics, taxation, and warehousing. In combination with the policy contents, the Chinese government has focused on the development of an “Internet + Customs” integrated online service platform for customs clearance services. For logistics services, the government has adopted the strategy of combining regulation and development, and the government has supported logistics enterprises in establishing a global logistics supply chain and overseas logistics service system, thus enhancing their competitiveness. What is more, the government has encouraged large e-commerce logistics enterprises to implement international development strategy and expand China’s cross-border e-commerce international logistics market through network connections with important hubs in developed countries.

Cluster 2 comprises regulatory targets, primarily involving cross-border e-commerce goods, data, articles, transactions, and payments. Combining this with specific policy contents, we can note that, in regards to the payment link, the government has primarily regulated cross-border internet payment business to prevent cross-border capital flow risks in internet channels. In the transaction link, the government has proposed the verification of authenticity of elements such as the name, quantity, amount, transaction parties, transaction time, and other information comprising the subject matter of the transaction, and has required the retention of relevant information for five years for future reference. In the links related to goods and articles, the government has primarily supervised orders, logistics information, packaging, labeling, and other aspects of goods and articles. In the data link, the government has emphasized the analysis and monitoring of cross-border bonded imported goods data, e-commerce companies, and consumer information data.

Cluster 3 comprises specific measures, including international cooperation, demonstration construction, service system construction, and risk monitoring. In combination with relevant policy contents, we observe that the government has continued to increase the number of pilots related to the cross-border e-commerce online purchase bonded import model and foreign exchange payment business, as well as launching a cross-border e-commerce service pilot and comprehensive pilot area and clarifying the implementation plan and regulatory rules of the above pilot. In terms of risk monitoring, the government has explored the ways in which a risk monitoring system could be established, formulated a supervisory list of key commodities and projects, and established a quality risk information collection mechanism, a risk assessment and analysis mechanism, and an early risk warning and disposal mechanism. In terms of international cooperation, the government actively initiated or participated in negotiation, exchange, and cooperation with multilateral countries regarding e-commerce rules, and examined ways to establish a mutual recognition mechanism between China and internationally recognized organizations.

Cluster 4 comprises the basic support capability, including product quality and safety and technical standards. Further combining specific policy contents, the government implemented a record-keeping management system for cross-border e-commerce business entities and commodities, clarified the responsibility of enterprises in terms of quality and safety, and realized quality and safety traceability, thereby ensuring that responsibility can be investigated. In terms of the technical aspect, the government has supervised technical requirements, risks, and infrastructure.

In summary, clusters 2 and 4 comprise the main targets used by the government to regulate the development of cross-border e-commerce with different focuses. Therefore, this paper combines these two clusters into one category, and then integrates the cross-border e-commerce policy keyword network into three categories, namely (1) service contents, (2) regulatory targets, and (3) policy measures. Thus, a three-dimensional framework of cross-border e-commerce policies can be constructed. In the next section, the contents of the policy documents are analyzed with regards to those three categories in a dynamic setting.

4.2. Policy Structure Analysis

Based on the three-dimensional framework of cross-border e-commerce policy constructed in the previous sub-section, we will further explore the sustainability of cross-border e-commerce policy structure in China. Specifically, the manifestations of specific policy elements (contents) are analyzed with time for the given sample of the policy documents. Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 present the results for each category of the policy elements.

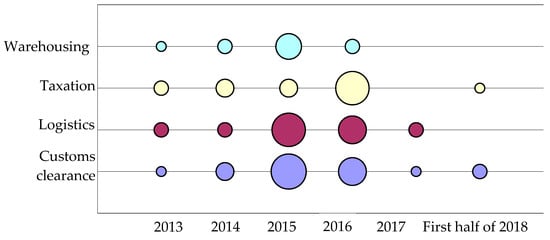

Figure 2.

Dynamic distribution of China’s cross-border e-commerce policy documents in terms of service contents.

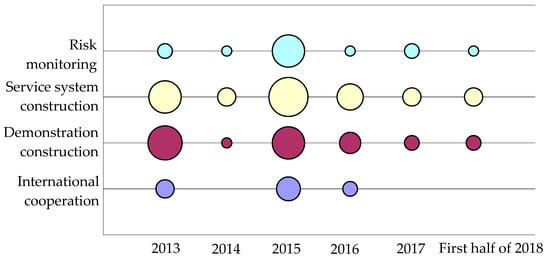

Figure 3.

Dynamic distribution of China’s cross-border e-commerce policy documents in terms of policy measures.

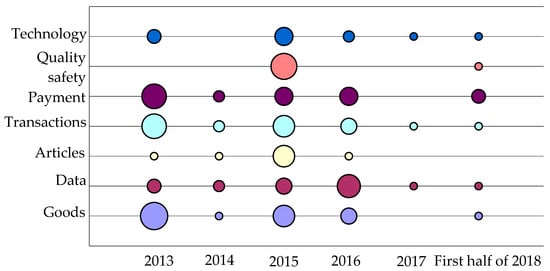

Figure 4.

Dynamic distribution of China’s cross-border e-commerce policy documents in terms of regulatory targets.

According to the dynamics in the number of service-related contents in the cross-border e-commerce policy documents (see Figure 2), the four policy elements show an upward trend from 2013 to 2015, when the number of policies related to warehousing, logistics, and customs clearance reach a peak. This suite is followed by a peak in the number of taxation-related policies in 2016. Subsequently, all of the policy elements followed a downward trend, yet the decline in the number of logistics and customs clearance policies was significantly slower than that in policies related to taxation and warehousing. The number of cross-border e-commerce policy documents involving service contents declined from 2017 onwards because of the difficulties associated with the existing service system’s in meeting the needs of cross-border e-commerce development. In 2014, the State Council issued policy documents requiring government authorities to optimize and improve customs clearance, logistics, warehousing, taxation, and other services. In 2015 and 2016, the General Administration of Customs, the Foreign Exchange Administration, the Ministry of Commerce, and other agencies formulated a number of cross-border e-commerce policies. These policies focused on improving customs clearance efficiency, combating illegal import and export, regulating customs clearance procedures, facilitating tax refunds (exemption), and establishing overseas warehousing facilities. It should be pointed out that the logistics link was the biggest constraint for cross-border e-commerce. Although the government had formulated some policies to encourage and support the development of cross-border e-commerce logistics, a few policies were particularly effective for its development, including management rules, regulatory requirements, support programs, and others. As a result, China’s cross-border e-commerce logistics companies still face environmental risks, market risks, transportation risks. This seriously restricts the development of cross-border e-commerce logistics [60,61]. Given the observations above, we argue that although the Chinese government has been increasingly focused on cross-border e-commerce services, regulations have mainly affected higher-level departments in the policymaking process, which is not sufficient for the further optimization and improvement of cross-border e-commerce services in China.

According to the dynamics in the documents on cross-border e-commerce defining the policy measures (see Figure 3), 2013 saw large numbers of the documents related to demonstration construction and service system construction, totaling to 10 and 9, respectively. These figures decreased in the following year, with an upswing in 2015. Obviously, the policies related to service system construction and demonstration construction demonstrate a steady growth trend (in cumulative terms), primarily because the General Administration of Customs and the State Council launched “cross-border e-commerce pilot cities” and a “cross-border e-commerce comprehensive pilot area,” in 2013 and 2015, respectively. In order to facilitate the smooth development of the demonstration construction, each department has since issued more supporting policies for cross-border e-commerce. In contrast, the number of international cooperation and risk monitoring policies only reached its peak in 2015, and remained low in subsequent years. This is because the State Council promulgated the “Opinions on Vigorously Developing E-commerce to Accelerate the Cultivation of New Economic Power” in 2015, requiring the Ministry of Commerce and the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine (AQSIQ) to strengthen international cooperation in e-commerce, and explore the establishment of a blacklist of cross-border e-commerce goods and a risk monitoring system. In response to the State Council’s request, the two agencies formulated a series of corresponding policies. However, duplicate supervision problems still exist in both agencies. In terms of a service system, each order for information needs to be submitted repeatedly to the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine, the General Administration of Customs and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange. In terms of demonstration construction, the General Administration of Customs and the State Council initiated the establishment of pilots in cities with good economic and foreign trade conditions. This rendered a certain overlap in urban planning and cross-border e-commerce promotion.

In contrast, international cooperation is the least exploited option among the four policy measures and has not been mentioned in documents from 2014, 2017, and the first half of 2018. This is in line with Lai and Wang [62,63]. Since cross-border e-commerce entails trade among countries, and each country has different legal systems and regulatory mechanisms, it is necessary to establish a unified trade cooperation mechanism through exchange and mutual cooperation. Currently, it is necessary for the government to initiate and lead the establishment of the supervision mechanism for multilateral dialogue and cooperation related to cross-border e-commerce. This would allow increasing opportunities for cross-border e-commerce enterprises to expand globally. Therefore, the Chinese government should pay more attention to international cooperation in cross-border e-commerce.

In regards to the China’s cross-border e-commerce policy measures, it is obvious that the government focused on the implementation of the service system and the demonstration construction policy in the early stage of development, and then began to emphasize the coordinated implementation of multiple measures in 2015. This suggests that China’s cross-border e-commerce policy shifted from a reliance on a single measure to the comprehensive utilization of various policy measures. This allowed a promotion of the development of cross-border e-commerce through the synergy among cross-border e-commerce policy measures.

Turning to the dynamics in cross-border e-commerce policy regulatory targets (Figure 4), the number of policies related to payment, transactions, and goods reached a peak in 2013 and decreased in the following year. In 2015, except for the number of policies related to data (which reached a peak in 2016), the number of policies for the other regulatory objects reached a peak and then showed a downward trend. It is clear that the number of policies related to payments, transactions, and goods follow a cyclical trend. Indeed, the degree of centrality in these keywords is high and rather similar, indicating that the government has formed a regulatory system focused on payments, transactions, and goods. This is because transaction, payments, and goods are the key links in the cross-border e-commerce supply chain, and problems related to these links would lead to serious systemic risks. It should be noted that the General Administration of Customs promulgated the “Affiche on Regulatory Issues Concerning Import and Export Goods and Articles of Cross-border Trade E-Commerce” in 2014, which defined the scope and requirements for the regulation of inbound and outbound goods. The AQSIQ promulgated the “Opinions Related to Further exerting the Role of Inspection and Quarantine Functions to Promote the Development of Cross-border E-commerce” in 2015 which also established a goods management system. It can be seen that there was a lack of effective communication among the regulatory authorities, resulting in repeated supervision and inconsistent systems.

The number of policy documents regarding the quality and safety reached its peak in 2015 and remained low in subsequent years. Because the rate of unqualified cross-border e-commerce commodities was as high as 33% in 2015, quality and safety problems have become more serious [64]. In order to solve this, the AQSIQ issued the “Opinions on Further Exerting the Role of Inspection and Quarantine Functions to Promote the Development of Cross-border E-commerce”, “Guiding Opinions on Strengthening the Inspection and Supervision of Cross-border E-commerce Import and Export Consumer Goods”, and “Rules on Supervision and Administration of Imported Food Safety in Cross-border E-commerce Bonded Online Mode (Draft for Comments)”, establishing a risk monitoring and quality traceability system for cross-border e-commerce. This system allows the traceability of quality, safety, and accountability measures, and also marks the maturity and systematization of the quality safety supervision system.

In summary, in the early stage of development of cross-border e-commerce, the government paid much attention to the supervision of payments, transactions, and goods. Later on, the focus was put on comprehensive supervision over all aspects of the cross-border e-commerce supply chain (beginning in 2015). Although the structure of policy targets was not balanced across different time periods with significant fluctuations, the number of regulatory targets and corresponding policies has been gradually increasing in general.

5. Research Limitations and Future Research

The research presented in this paper has the following limitations: First, this paper quantitatively analyzes the structural characteristics of China’s cross-border e-commerce policies, but does not systematically study (or compare) cross-border e-commerce policies of the other countries. Indeed, it is difficult to provide international experience in cross-border e-commerce policy formulation. In the future, we can opt for a comparative analysis of the characteristics of international cross-border e-commerce policies [65] and provide a basis for China to initiate and lead the establishment of a cross-border e-commerce multilateral dialogue cooperation supervision mechanism.

Second, in the process of research, this paper only considered the internal structure of the policy documents without considering the final implementation effect of the policy. In the future, we will look into the effects of different types of cross-border e-commerce policies. This will allow us to provide decision support for the government (by proposing more reasonable policy targets, for example).

Third, this paper only discusses the dynamic changes of policy service contents, policy regulatory targets, and policy measures. In fact, a study of the synergy among the three dimensions is meaningful for the country to formulate a support platform for cross-border e-commerce policies.

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

In this paper, we used the social network analysis method to explore the characteristics of 59 cross-border e-commerce policy documents promulgated by the Chinese government from January 2013 to July 2018. The weighted co-word matrix and cluster analysis were applied in order to ensure robustness of the analysis. The research quantitatively analyzed the internal structure and dynamic layout characteristics of sustainable cross-border e-commerce policy documents from three dimensions: policy service contents, policy regulatory targets, and policy measures. Among these, the service contents primarily included customs clearance, logistics, taxation, warehousing, and other comprehensive services for cross-border e-commerce trading enterprises. The regulatory targets included goods, data, articles, transactions, payments, quality and safety, and technical standards. The policy measures included international cooperation, demonstration construction, service system construction, and risk monitoring.

In terms of the dynamic sustainability, the cross-border e-commerce policy documents on service contents lacked long-term strategic planning, especially in regards to taxation and warehousing policies. Looking at the measures for promotion of cross-border e-commerce, the service system construction and demonstration construction policies follow a steady growth trend, whereas policies related to international cooperation and risk monitoring only peaked in 2015 and remained low in subsequent years. As regards the regulatory targets for cross-border e-commerce, the policy documents paid attention to the supervision of payments, transactions, and goods in the early stage of development, yet began conducting comprehensive supervision over all aspects of the cross-border e-commerce supply chain in 2015. Thus, a relatively mature regulatory system has been established with a particular focus on quality and safety.

The following policy implications can be derived: The macro-level and long-term policies on cross-border e-commerce should be maintained in China. While policy is both a norm and a guarantee, it is also a guidance direction. The Chinese government should play a leading role in market regulation. Specifically, it should conduct overall planning for different aspects and levels of cross-border e-commerce, balance the interests of all parties, and establish a mechanism of interest sharing. These could be achieved by simultaneously providing directions for participants and institutionalizing protection and supervision activities. Second, international cooperation in cross-border e-commerce should be strengthened. Government agencies should actively promote cross-border e-commerce rules and treaties among relevant countries. Furthermore, management systems and standards related to cross-border e-commerce customs clearance services, inspection and quarantine supervision mechanisms, and product quality safety supervision and traceability mechanisms should be proposed. In general, establishing a cross-border e-commerce international cooperation mechanism is required to create the necessary conditions for domestic enterprises to successfully carry out cross-border e-commerce activities. Third, the government should pay attention to the coordinated development of cross-border e-commerce services. Since cross-border e-commerce services involve different regulatory departments, and each government agency develops its own service system according to its responsibilities, poor coordination is imminent. This could negatively affect sustainability of the cross-border e-commerce regulation system. The Chinese government must evaluate and supervise service policies on a regular basis, according to the needs of cross-border e-commerce, and ensure monitoring of the effectiveness of these policies.

Author Contributions

Investigation, S.Z. and T.B.; Methodology, Y.W.; Supervision, W.S.; Writing—original draft, L.Q.; Writing—review & editing, T.B. and D.S.

Funding

This paper is supported by the Projects of National Social Science Fund of China (No. 16ZDA053, No. 18BTJ027).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X. The development trend of cross-border e-commerce and the promotion of China’s foreign trade transformation and upgrading. Commer. Times 2015, 23, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Su, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zeng, S. The economic effect of cross-border e-commerce technology shocks. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2018, 17, 549–566. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, X. Research on cross-border e-commerce driving innovation and development of China’s foreign trade. Mod. Manag. Sci. 2018, 298, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H. Analysis on the role of cross-border e-commerce in the development of small and medium-sized foreign trade enterprises. Commer. Time 2014, 31, 61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, W.; Zhong, X. Study on the Cross-border EC of China’s Foreign Trade Export Enterprises. Prices Mon. 2015, 12, 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X. Analysis on the transformation and upgrade strategy of small and medium-sized agricultural products foreign trade enterprises under the background of cross-border e-commerce. Agric. Econ. 2016, 11, 138–139. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y. The development status and operation mode of cross-border e-commerce development in China in the network age. Commer. Times 2017, 2, 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Zhong, W.; Sun, W. The measurement and the coordinated evolution of policies, and economic performance: A case study on the policy for innovation. Manag. World 2008, 9, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Xiong, C.; Xu, H.; Liu, N. The security issues and regulatory advice of cross-border e-commerce. China Bus. Trade 2014, 32, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Tang, W. Study on the topic of cross-border e-commerce development and its government regulation in China. Shanghai J. Econ. 2014, 9, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Du, G. Research on the development status and supervision countermeasures of cross-border e-commerce in China. Study China Adm. Ind. Commer. 2015, 10, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B. The development of cross-border e-commerce in China and the government regulation-Taking small cross-border e-commerce as example. Reform. Strateg. 2017, 1, 133–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y. The development trend and development policy of cross-border e-commerce in China. Dev. Res. 2016, 4, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Li, W.; Li, Y. Research and analysis on cross-border e-commerce legal policies. E-Bus. J. 2017, 11, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, J. A Probe into the Development of Cross-border E-commerce Policy in China. E-Bus. J. 2017, 9, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- E, L.; Huang, Y. New ways in international trade: The latest research on cross-border e-commerce. J. Dongbei Univ. Financ. Econ. 2014, 2, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, R. The innovation and implementation measures of Fujian free trade zone on Taiwan’s cross-border e-commerce. Econ. Relat. Trade 2016, 1, 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Xu, D. Analysis on the development strategy of cross-border e-commerce in Guangdong province. J. Commer. Econ. 2016, 6, 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z. The development status and improvement strategy of cross-border retail e-commerce under the “Internet +” environment. Commer. Times 2017, 6, 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Zhu, L. New developments and new issues of China’s cross-border e-commerce exports in the new situation—Thoughts based on WTO multilateral trade rules. Econ. Relat. Trade 2017, 6, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Discussion on the development trend of cross-border e-commerce in China under the development trend of international e-commerce. Business 2013, 13, 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, N.; Liu, D. The development status and innovation path of cross-border e-commerce in China. Commer. Times 2015, 31, 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Guo, J. Legal issues concerning the supervision of cross-border electronic payment services by third-party payment agencies. Law Sci. 2015, 3, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Wei, J.; Wei, N. Research on building China’s cross-border e-commerce and payment foreign exchange management system. J. Reg. Financ. Res. 2013, 6, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Jiang, J. The current situation and countermeasures of cross-border e-commerce in China. Macroecon. Manag. 2015, 4, 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Wang, F. The current situation of cross-border e-commerce in China and the countermeasures. China Bus. Mark. 2015, 3, 110–111. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y. Research on flexible optimization strategy of supply chain for cross border electricity supplier in China. Reform. Strateg. 2017, 8, 142–145. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, H. Analysis of the prospects of China and Russia cross-border e-commerce trade development. Pract. Foreign Econ. Relat. Trade 2017, 4, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X. Discussion on supply chain flexible optimization strategy of cross-border e-commerce. Commer. Times 2018, 4, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. Discussion on the countermeasures of foreign exchange statistics monitoring under the situation of high foreign exchange surplus. J. Reg. Financ. Res. 2006, 3, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. Research on the legal supervision of third-party cross-border electronic payment services. J. Reg. Financ. Res. 2016, 2, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, C. The dilemma and solution ideas of third-party payment in expanding cross-border e-commerce. Commer. Times 2017, 8, 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, F. Construction strategy of cross-border e-commerce commodity quality supervision system under quality traceability. Commer. Times 2016, 9, 98–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Dai, J.; Ye, Y. Cross-border e-commerce: A new model for China’s foreign trade development. Mod. Bus. Trade Ind. 2016, 11, 37–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Hu, L. Problems and perfecting paths of China’s cross-border e-commerce supervision system. Econ. Relat. Trade 2017, 6, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Analysis on the development of cross-border e-commerce under the background of new economic normality. Commer. Times 2018, 7, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kan, N. Research on the effectiveness of government supporting policies in promoting the development of cross-border e-commerce—Based on complex network perspective. Zhejiang Soc. Sci. 2016, 10, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Yang, J. Mechanism of government policies in cross-border e-commerce on firm performance and implications on m-commerce. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2017, 15, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X. Research on the influence spreading model of policies and regulations in the cross-border e-commerce trade. China Bus. Mark. 2018, 1, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, R.; Zegveld, W. Industrial Innovation and Public Policy: Preparing for the 1980s and the 1990; Frances Printer: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Lowi, T.J. Four systems of policy, politics, and choice. Public Adm. Rev. 1972, 32, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Ramesh, M. Studying Public Policy: Policy Cycles and Policy Subsystems; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonnell, L.M.; Elmore, R.F. Getting the job done: Alternative policy instruments. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1987, 9, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Su, J.; Shi, L.; Cheng, X. Textual and quantitative research on Chinese wind energy policy system from the perspective of policy tools. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2011, 29, 876–882. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Su, J.; Shi, L.; Cheng, X. Textual and quantitative research on China’s tax preferential policies for high-tech industries. Sci. Res. Manag. 2011, 32, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Liu, W. Quantitative research on the policy texts of China’s pension service industry (1994~2016). Reform Econ. Syst. 2017, 4, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kan, Z.; Zhang, G. Study on the text mining and Chinese text mining framework. Inf. Sci. 2007, 25, 1046–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, C.C.; Zhai, C.X. Mining Text Data; Springer Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaki, T.; Okazaki, M.; Matsuo, Y. Tweet analysis for real-time event detection and earthquake reporting system development. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2013, 25, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, E.W.T.; Lee, P.T.Y. A review of the literature on applications of text mining in policy making. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Chiayi, Taiwan, 27 June–1 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weishaar, H.; Amos, A.; Collin, J. Best of enemies: Using social network analysis to explore a policy network in European smoke-free policy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 133, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varone, F.; Ingold, K.; Jourdain, C.; Schneider, V. Studying policy advocacy through social network analysis. Eur. Political Sci. 2016, 16, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, J. Research on the internal structural relation and macro layout of scientific and technological achievements transformation policies based on text mining. J. Intell. 2016, 35, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Wang, S.; Su, J.; Zhao, P. A social network analysis of changes in China’s education policy information transmission system (1978–2013). High. Educ. Policy 2018, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Social Network Analysis; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Ren, W.; Wu, G. The characteristics of agricultural trade network and its effects on the global value chain division: A study based on social network analysis. Manag. World 2016, 3, 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Ma, X.; Bi, Q. Comparative study of the social network analysis tools: Ucinet and gephi. Inf. Stud. Theory Appl. 2014, 8, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- E, L.; Liu, Z. Research on the sunshine customs clearance of cross-border e-commerce. Int. Trade 2014, 9, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Create a green channel for cross-border e-commerce in the Silk Road Economic Belt. China Post 2015, 7, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, T. Difficulties and countermeasures about China’s cross-border e-commerce logistics. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2015, 5, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Sun, X. A study of cross-border e-commerce risk management model based on the SD method. Commer. Res. 2017, 12, 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y.; Wang, K. Cross-border electronic commerce’s development characteristics, obstacle factors and the next step in China. Reform 2014, 5, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. On international harmonization of rules on cross-border e-commerce. Rev. Cust. Law 2015, 5, 36–55. [Google Scholar]

- AQSIQ Released the Quality Inspection of Cross-Border E-Commerce Imported Consumer Goods in 2015, the Unqualified Rate Was 33%. Available online: http://www.cqn.com.cn/news/zgzlb/diyi/1131786.html (accessed on 16 March 2016).

- Georgescu, C.E.; Spatariu, E.C. The Informational and Decisional Approach in Management Accounting. The Case of Romania. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2017, 16, 367–386. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).