User Acceptance of Mobile Apps for Restaurants: An Expanded and Extended UTAUT-2

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology

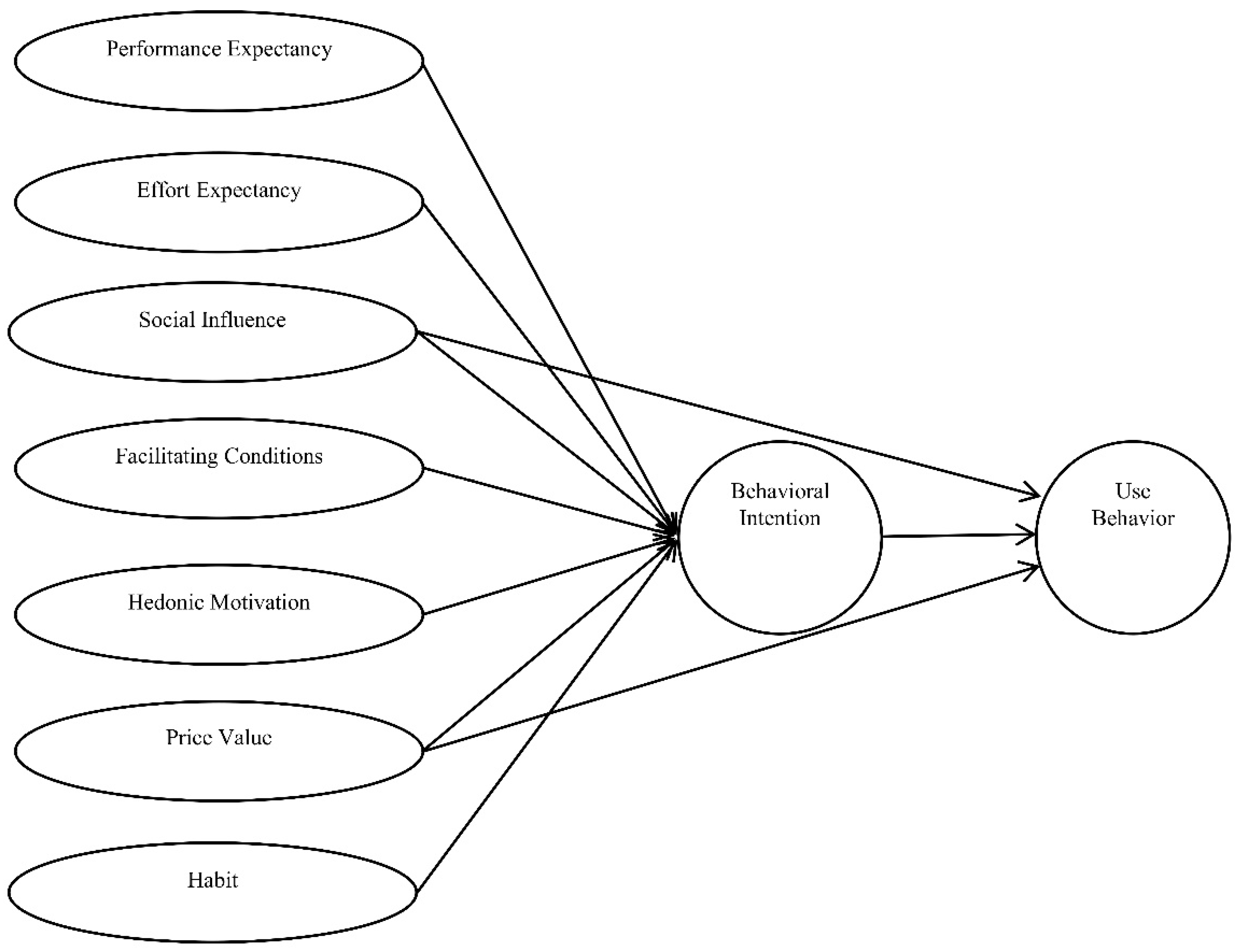

2.2. Research Model

2.3. Hypotheses Development

2.4. The Expanded and Extended UTAUT-2

3. Methodology

3.1. Instrument Development

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Method of Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Results

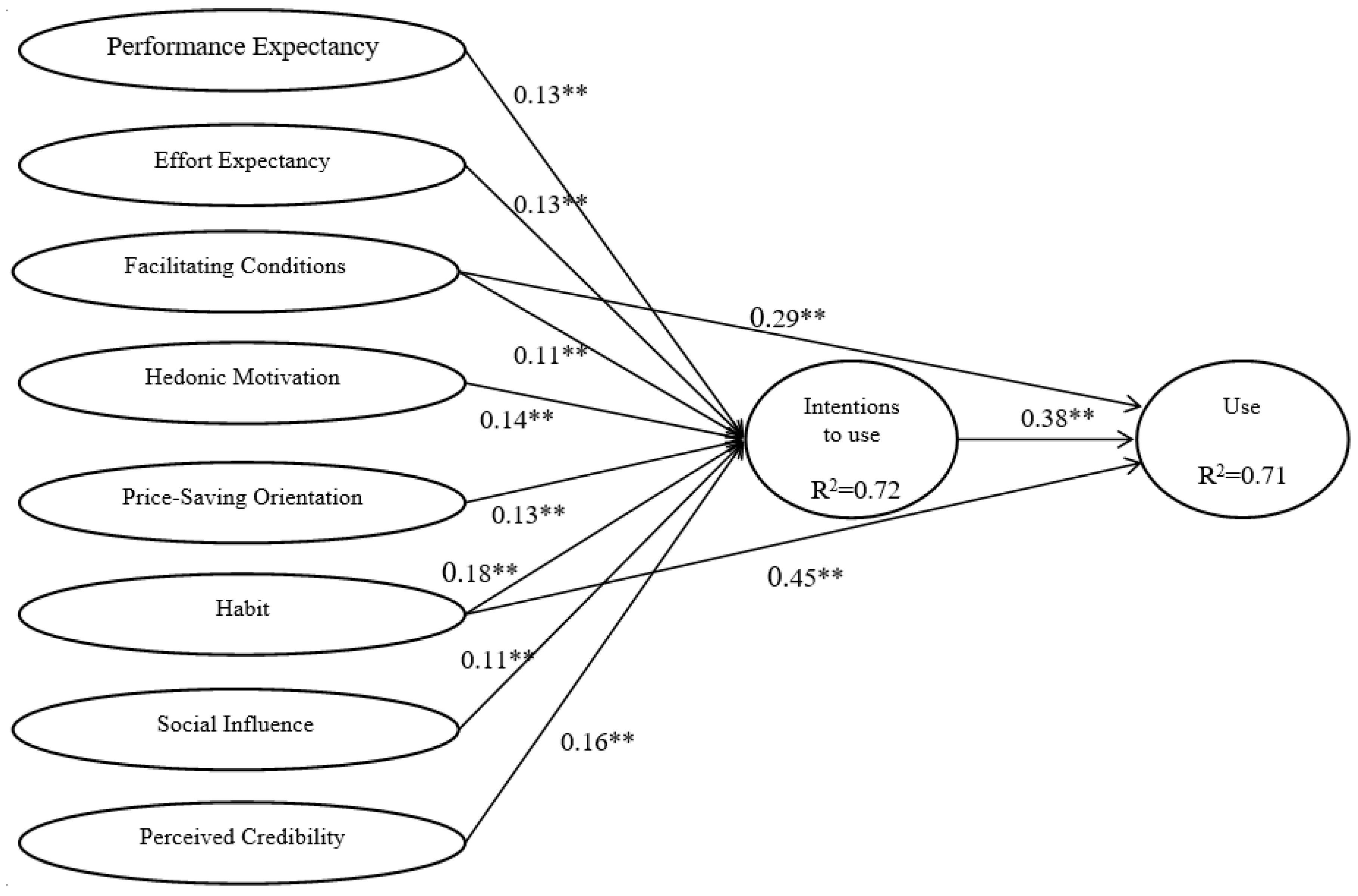

4.2. Structural Model Results

4.3. The Moderating Effects Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusion

6. Practical Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statista. Smartphone Users Worldwide 2014–2020. 2018. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-of-smartphone-users-worldwide/ (accessed on 17 October 2018).

- Statista. Annual Number of Global Mobile App Downloads 2017–2022. 2018. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/271644/worldwide-free-and-paid-mobile-app-store-downloads/ (accessed on 17 October 2018).

- Statista. Pre-Dining Smartphone Usage in the U.S. 2016. 2018. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/609812/activities-carried-out-by-diners-on-their-smartphones-us/ (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Dickinson, J.E.; Ghali, K.; Cherrett, T.; Speed, C.; Davis, N.; Norgate, S. Tourism and the smartphone app: Capabilities, emerging practice and scope in the travel domain. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinch, T.; Higham, J. Sport Tourism Development, 2nd ed.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pareigis, J.; Edvardsson, B.; Enquist, B. Exploring the role of the service environment in forming customer’s service experience. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2011, 3, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Cheng, C.C.; Ai, C.H. A study of experiential quality, experiential value, trust, corporate reputation, experiential satisfaction and behavioral intentions for cruise tourists: The case of Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim (Sunny), J. An extended technology acceptance model in behavioral intention toward hotel tablet apps with moderating effects of gender and age. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1535–1553. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.B.; Kim, T.T.; Shin, S.W. Modeling roles of subjective norms and eTrust in customers’ acceptance of airline B2C eCommerce websites. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Xiong, L.; Hu, C. The effect of Facebook users’ arousal and valence on intention to go to the festival: Applying an extension of the technology acceptance model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Wang, S.H. Predicting mobile hotel reservation adoption: Insight from a perceived value standpoint. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrier, T.; Erdem, M.; Brewer, P. Merging task-technology fit and technology acceptance models to assess guest empowerment technology usage in hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2010, 1, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, A.B.; Nusair, K.; Okumus, F.; Hua, N. The role of utilitarian and hedonic values on users’ continued usage intention in a mobile hotel booking environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; So, K.K.F.; Hudson, S. Inside the sharing economy Understanding consumer motivations behind the adoption of mobile applications. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2218–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Li, H.T.; Li, C.R.; Zhang, D.Z. Factors affecting hotels’ adoption of mobile reservation systems: A technology-organization-environment framework. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Rodríguez, T.; Carvajal-Trujillo, E. Online purchasing tickets for low-cost carriers: An application of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) model. Tour. Manag. 2014, 43, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.K.V. Traveler acceptance of an app-based mobile tour guide. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 401–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, K.; Shin, H.; Hwang, J. Acceptance Factors of Appropriate Technology: Case of Water Purification Systems in Binh Dinh, Vietnam. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, F.; Ali, F.; Bilgihan, A.; Ozturk, A.B. Psychological factors influencing customers’ acceptance of smartphone diet apps when ordering food at restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 72, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. Understanding mobile Internet continuance usage from the perspectives of UTAUT and flow. Inf. Dev. 2011, 27, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín, H.; Herrero, A. Influence of the user’s psychological factors on the online purchase intention in rural tourism Integrating innovativeness to the UTAUT framework. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.S. Factors affecting individuals to adopt mobile banking: Empirical evidence from the UTAUT Model. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 13, 104–121. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L.Y.; Chang, S.C.; Sun, C.C. A three-stage model for smart phone use antecedents. Qual. Quant. 2014, 48, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Locke, S.-P.; Ooi, K.-B. Mobile TV: A new form of entertainment? Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 1050–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, E.L.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Piercy, N.C.; Williams, M.D. Modeling consumers’ adoption intentions of remote mobile payments in the United Kingdom: Extending UTAUT with innovativeness, risk, and trust. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 860–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosan, C.; DeFranco, A. It’s about time: Revisiting UTAUT2 to examine consumers’ intentions to use NFC mobile payment in hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 53, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coves Martínez, A.L.; Sabiote-Ortiz, C.M.; Rey-Pino, J.M. The influence of cultural intelligence on intention of internet use. Span. J. Mark. 2018, 22, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Tseng, T.H.; Wang, W.T.; Shiyh, Y.W.; Chan, P.Y. Developing and validating a mobile catering app success model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, A.; Laumer, S.; Weitzel, T. Computer self efficacy: Development of a measure and initial test. J. Inf. Technol. 2009, 24, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganthi, B. Internet banking patronage: An empirical investigation of Malaysia. J. Internet Bank. Commer 2001, 6, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, B.; Dasgupta, S.; Gupta, A. Adoption of ICT in a government organization in a developing country: An empirical study. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2008, 17, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Faria, M.; Thomas, M.A.; Popovic, A. Extending the understanding of mobile banking adoption: When UTAUT meets TTF and ITM. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, M. New media and the changing face of information technology use: The importance of task pursuit, social influence, and experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: A synthesis and the road ahead. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 17, 328–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1111–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azjen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Inf. Syst. Res. 1995, 6, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.; Higgins, C.; Howell, J. Personal computing: Toward a conceptual model of utilization. MIS Q. 1991, 15, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.C.; Benbasat, I. Development of an instrument to measure the perceptions of adopting an information technology innovation. Inf. Syst. Res. 1991, 2, 192–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compeau, D.R.; Higgins, C.A. Computer self-efficacy: Development of a measure and initial test. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, I.; Hong, S.; Kang, M.S. An international comparison of technology adoption. Testing the UTAUT model. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrero, J.D.; Yousafzai, S.Y.; Javed, U.; Page, K.L. Expressive participation in Internet social movements: Testing the moderating effect of technology readiness and sex on students SNS use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abroud, A.; Choong, Y.V.; Muthaiyah, S.; Fie, D.Y.G. Adopting e-finance: Decomposing the technology acceptance model for investors. Serv. Bus. 2015, 9, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-S.; Wang, Y.-M.; Lin, H.-H.; Tang, T.-I. Determinants of user acceptance of internet banking: An empirical study. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2003, 14, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.; Maruping, L.; Bala, H. Predicting different conceptualizations of system use: The competing roles of behavioral intention, facilitating conditions, and behavioral expectation. MIS Q. 2008, 32, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallivan, M.J.; Spitler, V.K.; Koufaris, M. Does information technology training really matter? A social information processing analysis of coworkers’ influence on IT usage in the workplace. J. Manag. Inform. Syst. 2005, 22, 153–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua, A.J.; Koshy, M.P. Usage patterns of electronic banking services by urban educated customers: Glimpses from India. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2011, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.; Venkatesh, V. Model of Adoption of Technology in Households: A Baseline Model Test and Extension Incorporating Household Life Cycle. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chtourou, M.S.; Souiden, N. Rethinking the TAM model: Time to consider fun. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Chan, H.; Gupta, S. Value-based adoption of mobile internet: An empirical investigation. Decis. Support Syst. 2007, 43, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanudin, A.; Rostinah, S.; Masmurniwati, M.A.; Ricardo, B. Receptiveness of mobile banking by Malaysian local customers in Sabah: An empirical investigation. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2012, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of price, brand and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Punj, G. Income effects on relative importance of two online purchase goals: Saving time versus saving money? J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Cho, Y.C.; Lee, S. Online shoppers’ response to price comparison sites. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2079–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.M. Shopping orientation and online travel shopping: The role of travel experience. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limayem, M.; Hirt, S.; Cheung, C. How Habit Limits the Predictive Power of Intention: The Case of Information Systems Continuance. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 705–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Attitude and Attitude Change; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, A.D. From reactive to proactive prevention: Promoting an ecology of health on campus. In Substance Abuse on Campus: A Handbook on Substance Abuse for College and University Personnel; Rivers, P.C., Shore, E., Eds.; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 1997; pp. 120–139. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, H.W. The emergence and evolution of the social norms approach to substance abuse prevention. In The Social Norms Approach to Preventing School and College Age Substance Abuse; Perkins, H.W., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, M.; Gerard, H.B. A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgement. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1955, 51, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kelman, H.C. Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change. J. Confl. Resolut. 1958, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.M. Norms: The concept of norms. In International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences; Sills, D.I., Ed.; McMillan: Mahwah, NJ, USA; New York, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 204–208. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; Terry, D.J.; Manstead, A.S.R.; Louis, W.R.; Kotterman, D.; Wolfs, J. The attitude–behavior relationship in consumer conduct: The role of norms, past behavior, and self-identity. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 148, 311–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 24, 201–234. [Google Scholar]

- Lapinski, M.K.; Rimal, R.N. An explication of social norms. Commun. Theory 2005, 15, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.W.; Park, H.S. Distinctiveness and influence of subjective norms, personal descriptive and injunctive norms, and societal descriptive and injunctive norms on behavioral intent: A case of two behaviors critical to organ donation. Hum. Commun. Res. 2007, 33, 194–218. [Google Scholar]

- Soroa-Koury, S.; Yang, K.C.C. Factors affecting consumers’ responses to mobile advertising from a social norm theoretical perspective. Telemat. Inform. 2010, 27, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luarn, P.; Lin, H.-H. Toward an understanding of the behavioral intention to use mobile banking. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2005, 21, 873–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, T.-T.; Sun, S. Exploring gender differences in Islamic mobile banking acceptance. Electron. Commer. Res. 2014, 14, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, S.; Chau, P.Y.K.; Cao, Y. Dynamics between the trust transfer process and intention to use mobile payment services: A cross-environment perspective. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambourakis, G.; Martínez, G.; Mármol, F.G. Editorial: Special issue on advances in security and privacy for future mobile communications. Electron. Commer. Res 2015, 15, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforet, S.; Li, X. Consumers’ attitudes towards online and mobile banking in China. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2005, 23, 362–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A.; Hone, K.; Liu, X. Measuring the moderating effect of gender and age on e-learning acceptance in England: A structural equation modeling approach for an extended technology acceptance model. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2014, 51, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, J.A.; Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Luque, T. Web Acceptance Model (WAM): Moderating effects of user experience. Inf. Manag. 2007, 44, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, P.; Morahan-Martin, J. Gender, Internet and computer attitudes and experiences. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2000, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, P.D.; Gilkeson, J.H.; List, J.A. Gender differences in revealed risk taking: Evidence from mutual fund investors. Econ. Lett. 2002, 76, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín, S.; Jiménez, N.H. Online buying perceptions in Spain: Can gender make a difference? Electron. Mark. 2011, 21, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Guo, Y. Antecedents of trust and continuance intention in mobile payment platforms: The moderating effect of gender. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 33, 100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y. The privacy–personalization paradox in mHealth services acceptance of different age groups. Electron. Commer. Res. 2016, 16, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netquest. Available online: https://www.netquest.com/online-surveys-investigation (accessed on accessed on 17 October 2018).

- Bentler, P.M. EQS Structural Equations Program Manual; Multivariate Software Inc.: Encino, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bandalos, D.L.; Finney, S.J. Item parceling issues in structural equation modelling. In Advanced Structural Equation Modeling: New Developments and Technique; Marcoulides, G.A., Schumacker, R.E., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 269–296. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, T. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equations models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkzadeh, G.; Koufteros, X.A.; Pflughoeft, K. Confirmatory analysis of a computer self-efficacy instrument. Struct. Equ. Model. 2003, 10, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson New International Edition Macmillan: Harlow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. PRELIS 2 User’s Reference Guide: A Program for Multivariate Data Screening and Data Summarization: A Preprocessor for LISREL; Scientific Software International: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Lu, Y.; Gupta, S.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, R. Mobile payment services adoption across time: An empirical study of the effects of behavioural beliefs, social influences, and personal traits. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K. Determinants of US consumer mobile shopping services adoption: Implications for designing mobile shopping services. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouthuysen, K.; Teunis, I.; Reusen, E.; Slabbinck, S. Initial trust and intentions to buy: The effect of vendor-specific guarantees, customer reviews and the role of online shopping experience. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 27, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palau-Saumell, R.; Forgas-Coll, S.; Sánchez-García, J.; Prats-Planagumà, L. Managing dives centres: SCUBA divers’ behavioural intentions. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 422–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgas-Coll, S.; Palau-Saumell, R.; Matute, J.; Tárrega, S. How do service quality, experience and enduring involvement influence tourists behavior: An empirical study in the Picasso and Miró museums in Barcelona. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor Loading | t | |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptive Personal Norm (AVE = 0.85; CR = 0.94) | ||

| I believe that many people who are important to me use MARSR. | 0.89 | 42.49 ** |

| I believe that many people whose opinions I value use MARSR. | 0.94 | 46.18 ** |

| I believe that many people who are important to me search for restaurants using MARSR. | 0.92 | 44.31 ** |

| Descriptive Social Norm (AVE = 0.74; CR = 0.88) | ||

| I believe that many people in my country use MARSR. | 0.88 | 36.79 ** |

| I believe that many people in my country express their desire to use MARSR. | 0.73 | 27.17 ** |

| I believe that many people in my country search for restaurants using MARSR. | 0.90 | 36.09 ** |

| Injunctive Personal Norm (AVE = 0.86; CR = 0.95) | ||

| I believe that many people whose opinions I value approve of my using MARSR. | 0.91 | 42.52 ** |

| I believe that many people who are important to me support my using MARSR. | 0.93 | 42.69 ** |

| I believe that many people who are important to me support my searching for restaurants using MARSR. | 0.93 | 44.36 ** |

| Injunctive Social Norm (AVE = 0.85; CR = 0.94) | ||

| I believe that many people in my country approve of the use of MARSR. | 0.92 | 40.11 ** |

| I believe that many people in my country support the use of MARSR. | 0.91 | 37.23 ** |

| I believe that many people in my country are in favor of searching for restaurants using MARSR. | 0.92 | 38.86 ** |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive Personal Norm | 0.92 a | |||

| Descriptive Social Norm | 0.51 **b | 0.86 | ||

| Injunctive Personal Norm | 0.61 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.93 | |

| Injunctive Social Norm | 0.47 ** | 0.83 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.92 |

| Factor Loading | t | |

|---|---|---|

| Use (AVE = 0.88; CR = 0.88) | ||

| How much time do you spend using MARSR when you are looking for restaurants? | 0.85 | 22.17 ** |

| Intentions to use (AVE = 0.74; CR = 0.90) | ||

| I will always try to use MARSR. | 0.88 | 39.70 ** |

| I plan to continue to use MARSR frequently. | 0.82 | 38.16 ** |

| I intend to continue using MARSR in the future. | 0.88 | 38.23 ** |

| Performance Expectancy (AVE = 0.67; CR = 0.89) | ||

| I find MARSR useful in my daily life when searching for restaurants. | 0.76 | 29.37 ** |

| I believe that using MARSR helps me search for restaurants more quickly. | 0.84 | 33.84 ** |

| I believe that using MARSR increases my productivity when searching for restaurants. | 0.85 | 36.05 ** |

| I believe I can save time using MARSR when searching for restaurants. | 0.83 | 32.93 ** |

| Effort Expectancy (AVE = 0.72; CR = 0.91) | ||

| I believe that learning how to use MARSR is easy for me. | 0.84 | 32.12 ** |

| I believe that my interaction with MARSR is clear and understandable. | 0.88 | 36.56 ** |

| I find MARSR easy to use. | 0.91 | 39.82 ** |

| I believe it is easy for me to become skillful at using MARSR. | 0.76 | 28.83 ** |

| Facilitating Conditions (AVE = 0.59; CR = 0.85) | ||

| I believe that I have the necessary smartphone to use MARSR. | 0.73 | 21.24 ** |

| I believe that I have the necessary knowledge to use MARSR. | 0.83 | 28.21 ** |

| I feel comfortable using MARSR. | 0.80 | 30.51 ** |

| I believe MARSR are compatible with other technologies I use. | 0.71 | 24.67 ** |

| Hedonic Motivation (AVE = 0.75; CR = 0.90) | ||

| I believe that using MARSR is fun. | 0.85 | 34.62 ** |

| I believe that using MARSR is enjoyable. | 0.90 | 37.12 ** |

| I believe that using MARSR is very entertaining. | 0.86 | 37.01 ** |

| Price-Saving Orientation (AVE = 0.60; CR = 0.81) | ||

| I can save money by examining the prices of different restaurants when using MARSR. | 0.77 | 27.88 ** |

| I like to search for cheap restaurant deals when using MARSR. | 0.82 | 32.95 ** |

| I believe MARSR offer better value for my money. | 0.72 | 26.67 ** |

| Habit (AVE = 0.62; CR = 0.87) | ||

| The use of MARSR has become a habit for me. | 0.82 | 40.76 ** |

| I am in favor of using MARSR. | 0.77 | 30.51 ** |

| I feel the need to use MARSR. | 0.71 | 30.56 ** |

| Using MARSR on my smartphone has become natural to me. | 0.84 | 40.84 ** |

| Social Influence (AVE = 0.65; CR = 0.88) Items parceling | ||

| Personal Descriptive Norms | 0.75 | 25.71 ** |

| Societal Descriptive Norms | 0.84 | 33.21 ** |

| Personal Injunctive Norms | 0.78 | 27.22 ** |

| Societal Injunctive Norms | 0.85 | 33.53 ** |

| Perceived Credibility (AVE = 0.75; CR = 0.92) | ||

| When using MARSR on my smartphone, I believe that my information is kept confidential. | 0.82 | 37.16 ** |

| I believe that my searches are secure. | 0.87 | 41.21 ** |

| I believe that my privacy will not be breached. | 0.86 | 41.11 ** |

| I believe that the environment is safe. | 0.90 | 43.98 ** |

| Use | Intentions to use | Performance Expectancy | Effort Expectancy | Facilitating Conditions | Hedonic Motivations | Price-Saving Orientation | Habit | Social Influence | Perceived Credibility | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use | 0.94 a | |||||||||

| Intentions to use | 0.62 **b | 0.86 | ||||||||

| Performance Expectancy | 0.55 ** | 0.72 ** | 0.82 | |||||||

| Effort Expectancy | 0.30 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.70 ** | 0.85 | ||||||

| Facilitating Conditions | 0.36 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.74 ** | 0.77 | |||||

| Hedonic Motivations | 0.57 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.87 | ||||

| Price-Saving Orientation | 0.53 ** | 0.76 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.59 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.77 | |||

| Habit | 0.71 ** | 0.74 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.70 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.79 | ||

| Social Influence | 0.52 ** | 0.78 ** | 0.75 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.66 ** | 0.71 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.70 ** | 0.81 | |

| Perceived Credibility | 0.22 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.87 |

| H | Path | Path Coefficient | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Intentions to use → Use | 0.38 | 4.96 ** |

| H2 | Performance Expectancy → Intentions to use | 0.13 | 36.81 ** |

| H3 | Effort Expectancy → Intentions to use | 0.13 | 36.81 ** |

| H4 | Facilitating Conditions → Use | 0.29 | 4.96 ** |

| H5 | Facilitating Conditions → Intentions to use | 0.11 | 36.81 ** |

| H6 | Hedonic Motivation → Intentions to use | 0.14 | 36.81 ** |

| H7 | Price-Saving Orientation → Intentions to use | 0.14 | 36.81 ** |

| H8 | Habit → Intentions to use | 0.18 | 36.81 ** |

| H9 | Habit → Use | 0.45 | 4.96 ** |

| H10 | Social Influence → Intentions to use | 0.11 | 36.81 ** |

| H11 | Perceived Credibility → Intentions to use | 0.16 | 36.81 ** |

| Gender | Age | Experience | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Men (597) | Women (605) | 18–39 (605) | Over 40 (597) | 3 Years or Less (484) | More than 3 Years (718) |

| Intentions to use → Use | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.41 * |

| Performance Expectancy→Intentions to use | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| Effort Expectancy → Intentions to use | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| Facilitating Conditions → Use | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.38 ** |

| Facilitating Conditions→Intentions to use | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Hedonic Motivation → Intentions to use | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

| Price-Saving Orientation→Intentions to use | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| Habit → Intentions to use | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.19 |

| Habit → Use | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.52 *** |

| Social Influence → Intentions to use | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Perceived Credibility → Intentions to use | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.17 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palau-Saumell, R.; Forgas-Coll, S.; Sánchez-García, J.; Robres, E. User Acceptance of Mobile Apps for Restaurants: An Expanded and Extended UTAUT-2. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041210

Palau-Saumell R, Forgas-Coll S, Sánchez-García J, Robres E. User Acceptance of Mobile Apps for Restaurants: An Expanded and Extended UTAUT-2. Sustainability. 2019; 11(4):1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041210

Chicago/Turabian StylePalau-Saumell, Ramon, Santiago Forgas-Coll, Javier Sánchez-García, and Emilio Robres. 2019. "User Acceptance of Mobile Apps for Restaurants: An Expanded and Extended UTAUT-2" Sustainability 11, no. 4: 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041210

APA StylePalau-Saumell, R., Forgas-Coll, S., Sánchez-García, J., & Robres, E. (2019). User Acceptance of Mobile Apps for Restaurants: An Expanded and Extended UTAUT-2. Sustainability, 11(4), 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041210