Historical Enquiry as a Critical Method in Urban Riverscape Revisions: The Case of Belgrade’s Confluence †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Methodological Framework

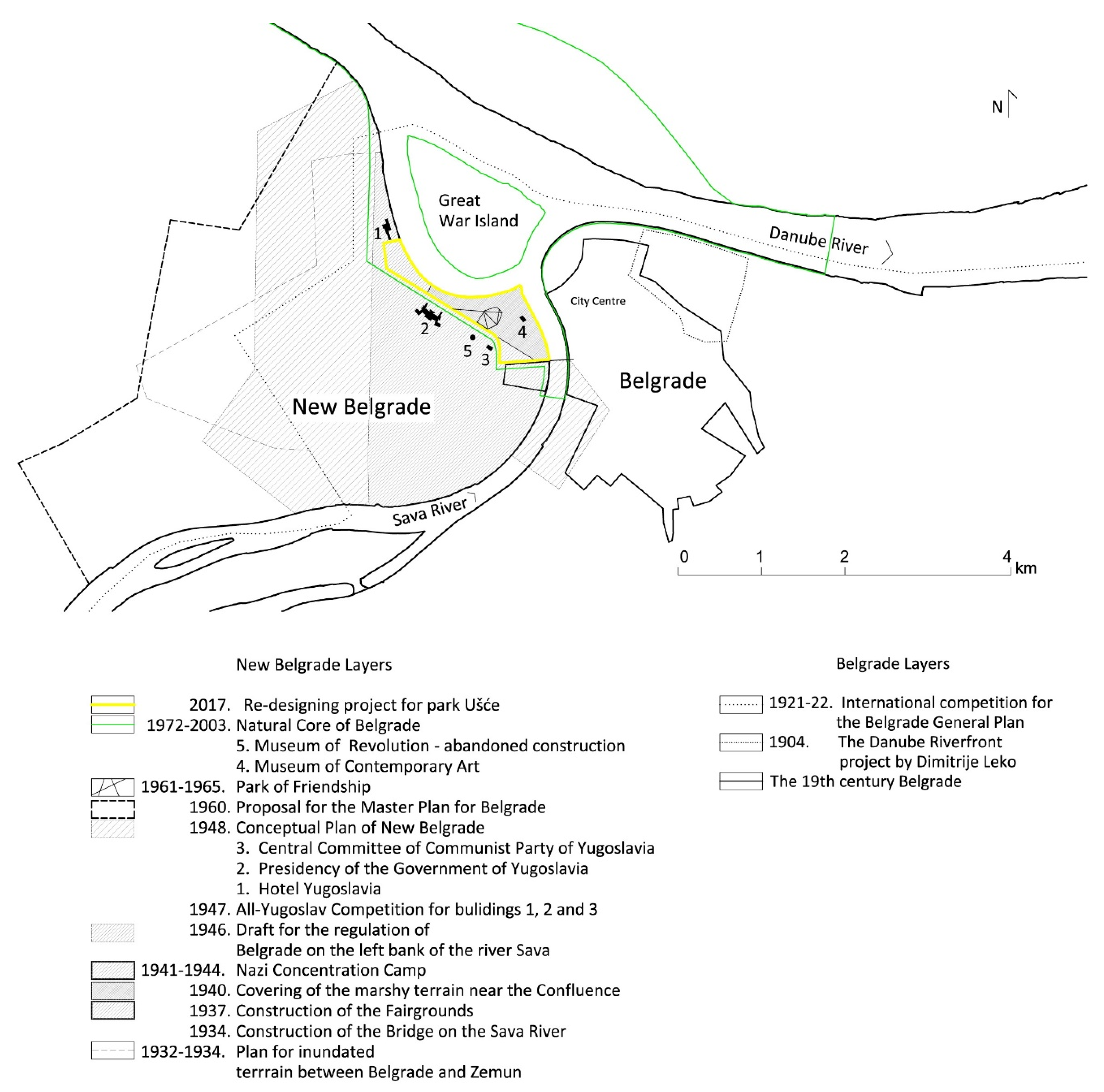

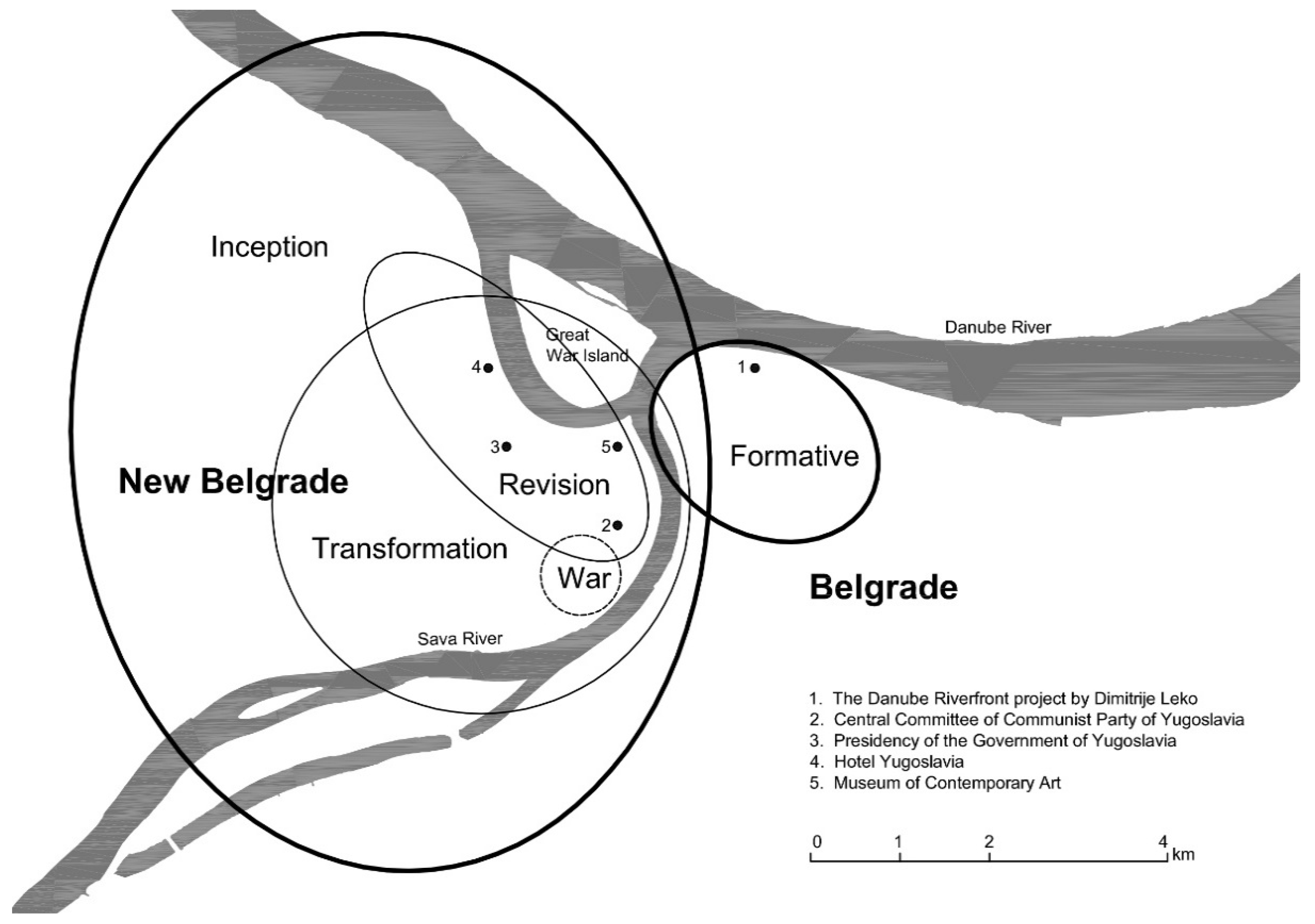

4. The Historical and Cultural Layers of Collective Memory

4.1. Layers of Belgrade Landscape of Modernisation: The Formative Period (1867–1914)

1904: Leko’s Project for the Danube Riverbank

4.2. Layers of New Belgrade Landscape: The Inception (1918–1940)

4.3. The War Landscape (1941–1945)

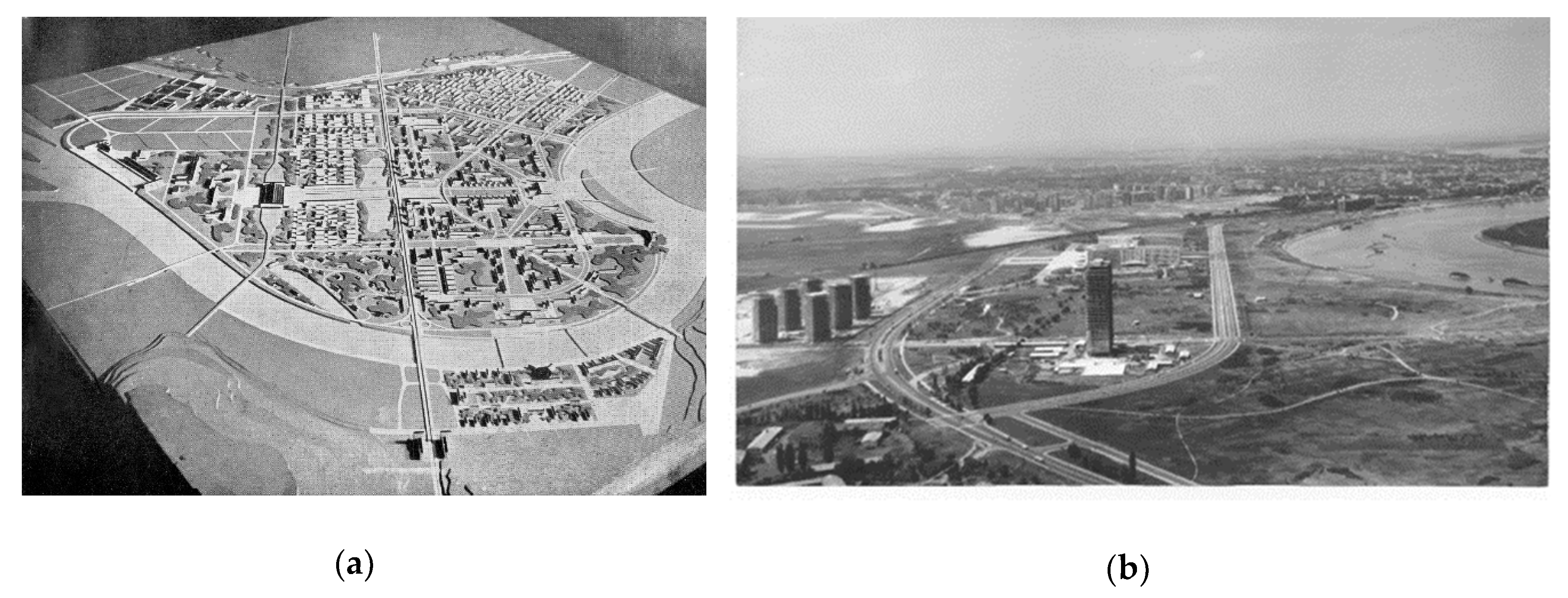

4.4. Post WWII Layers of New Belgrade Landscape: The Transformation (from 1946)

4.4.1. 1946: The Draft

4.4.2. 1947: The all-Yugoslav Competitions

4.4.3. 1948: The Conceptual Plan

4.5. Layers of New Belgrade Landscape: The Danube Riverfront Revisions (from 1960)

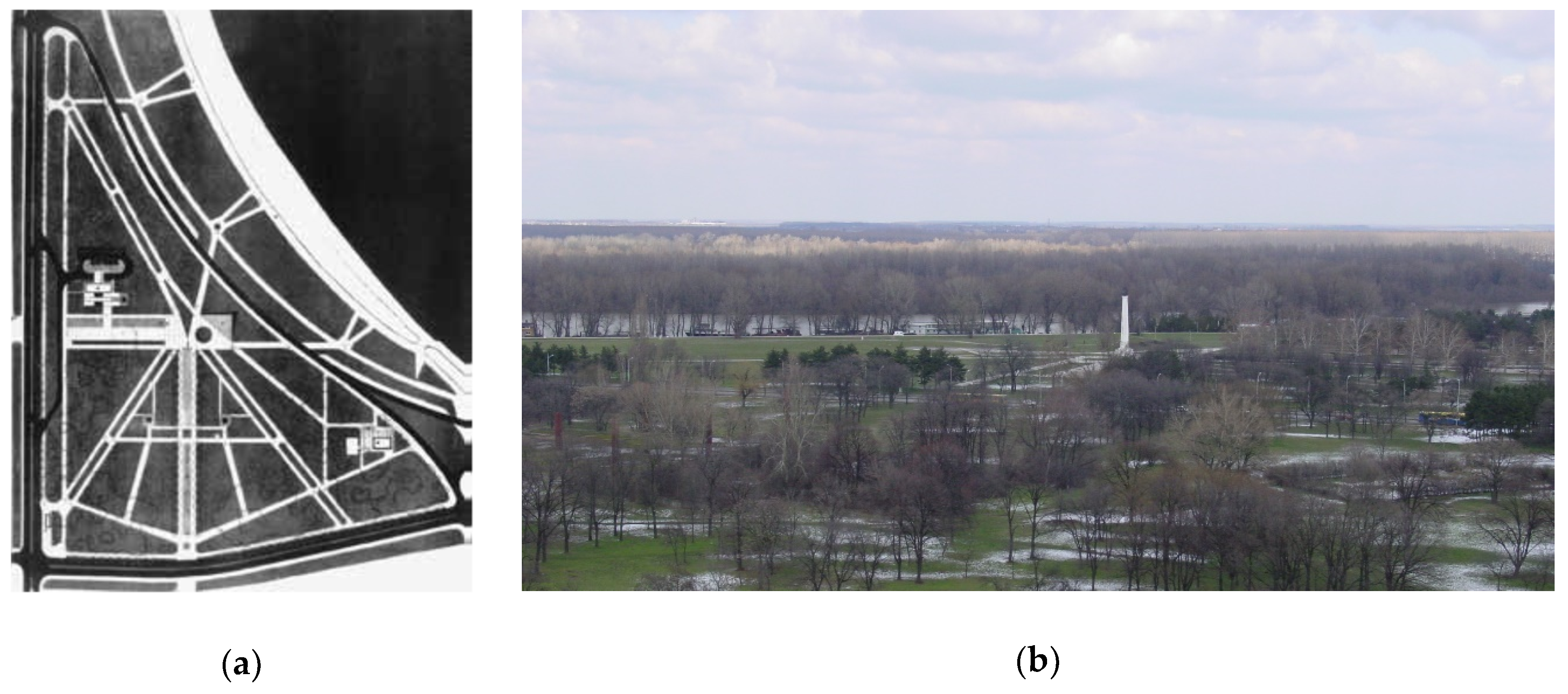

4.5.1. 1960: The Park of Culture, Science and Politics

4.5.2. 1961: The Park of Friendship and the Confluence

4.5.3. 1972–2003: The Natural Core of Belgrade

4.5.4. Epilogue

5. Discussion of the Case of Confluence

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lefebvre, H. Social Space. In The Production of Space, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 68–168. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, W.; Boelens, L. The Interaction of City and Water in the Yangtze River Delta, a Natural/Artificial Comparison with Euro Delta. Sustainability 2018, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, S.M. The Riverscape and the River; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Petričić, B. Ambijenti i prostorne vrednosti Beograda [Ambient and spatial values of Belgrade]. Godišnjak grada Beograda 1977, 24, 319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Ćorović, D.; Blagojević, L. Water, Society and Urbanization in the 19th Century Belgrade: Lessons for Adaptation to the Climate Change. SPATIUM Int. Rev. 2012, 28, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girot, C.H. Four Trace Concepts in Landscape Architecture. In Recovering Landscape, Essays in Landscape Architecture; Corner, J., Ed.; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Djalali, A.; Vollaard, P. The Complex History of Sustainability: An index of Trends, Authors, Projects and Fiction. 2008. Available online: https://rasmusbroennum.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/the-complex-history-of-sustainability-timeline.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Waldheim, C. The Landscape Urbanism Reader; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shennon, K. Landscapes. In The SAGE Handbook of Architectural Theory; Greig Crysler, C., Cairns, S., Heynen, H., Eds.; SAGE Publishing Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 625–638. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, J. Introduction: Recovering Landscape as a Critical Cultural Practice. In Recovering Landscape, Essays in Landscape Architecture; Corner, J., Ed.; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Toward an Urban Landscape. In Columbia Documents; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Berrizbeitia, A. Re-Placing Process. In Large Parks; Czerniak, J., Hargreaves, G., Eds.; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 174–197. [Google Scholar]

- Antrop, M. Why landscapes of the past are important for the future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 1–2, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHarg, I. Design with Nature; Published for the American Museum of Natural History; Natural History Press: Garden City, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Berrizbeitia, A.; M’Closkey, K. Critical Practices in Modernism: Origins in Nineteenth-Century American Landscape Architecture. In Modernism and Landscape Architecture, 1890–1940; O’Malley, T., Wolschke-Bulmahn, J., Eds.; The National Gallery of Art, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J.B. The Word Itself. In Discovering the Vernacular Landscape; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1984; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Antrop, M. A brief History of Landscape Research. In Landscape Reader; Howard, P., Thompson, I., Waterton, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, C.O. The Morphology of Landscape. Univ. Calif. Public. Geogr. 1925, 2, 19–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, J. Introduction. In Landscape (Key Ideas in Geography); Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Deriu, D.; Kamvasinou, K. Critical perspectives on landscape: Introduction. J. Arch. 2012, 1, 659896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćorović, D. Beograd kao evropski grad u devetnaestom veku: transformacija urbanog pejzaža [Belgrade as a European City in the Nineteenth Century: Urban Landscape Transformation]. Ph.D. Dissertation, Faculty of Architecture, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tafuri, M. Theories and History of Architecture; Granada: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Milinković, M. Arhitektonska kritička praksa: teorijski modeli [Architectural Critical Practice: Theoretical Models]. Ph.D. Dissertation, Faculty of Architecture, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leko, D.T. Revizija regulacionog plana prestonice i njenog građevinskog zakona III [The revision of the regulation plan of the capital and related law on construction]. Tehnički Glasnik [Tech. J.] 1901, 10, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, E. Hans Bernhard Reichow and the concept of Stadtlandschaft in German planning. Plan. Perspect. 2003, 2, 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagojević, L.J. Novi Beograd: osporeni modernizam [New Belgrade: Contested Modernism]; Zavod za udžbenike, Arhitektonski fakultet Univerziteta, Zavod za zaštitu spomenika: Belgrade, Serbia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrović, N. Što je gradski pejzaž—Njegova uloga i prednost u savremenom urbanizmu [What is the City Landscape—Its Role and the Advantage in Contemporary Urban Planning]. Čovjek i Prostor [Man Space] 1954, 20, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place, The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ćurčić, S. Period of Turmoil, circa 1250–Circa 1450. In Architecture in the Balkans: From Diocletian to Süleyman the Magnificent; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2010; pp. 507–702. [Google Scholar]

- Josimović, E. Objasnenje predloga za regulisanje onoga dela varoši Beograda, što leži u Šancu: sa jednim litografisanim planom u razmeri 1/3000 [Providing the Explanations of the Proposals Meant for Regulating the Part of Belgrade that Is Situated in the Moat, by a Lithographic Plan Scaled 1/3000]; E. Josimović: Belgrade, Serbia, 1867. [Google Scholar]

- Vuksanović-Macura, Z. San o gradu: međunarodni konkurs za urbanističko uređenje Beograda 1921–1922 [Vision of the City: International Urban Planning Competition for Belgrade 1921–1922]; Orion Art: Belgrade, Serbia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vuksanović-Macura, Z. Generalni plan Beograda 1923: komparacija planiranog i ostvarenog [Belgrade’s General Plan 1923: A Comparison of Planned to Completed]. Ph.D. Dissertation, Faculty of Architecture, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Blagojević, L.J. Realpolitik of Space: Sustenance of the Belgrade Fairground. In Stockholm-Belgrade, Proceedings of the 4th Swedish-Serbian Symposium: Sustainable Development and the Role of Humanistic Disciplines, Belgrade, Serbia, 2–4 October 2008; Palavestra, P., Ed.; Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts: Belgrade, Serbia, 2009; pp. 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- The Open University. Centre for Citizenship, Identities and Governance. Available online: http://www.open.ac.uk/ccig/research/projects/semlin-judenlager-in-serbian-public-memory (accessed on 26 May 2017).

- Dobrović, N.; Marković, V. Železnički problem Beograda [The Railroad Problem of Belgrade]; Urbanistički institut NRS: Belgrade, Serbia, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Obrazloženje [Explication]; document of the Ministry of Construction of Serbia, the Institute of Urban Planning, the Fund of the Ministry of Construction of FNRJ, F 94; Archive of Yugoslavia: Belgrade, Serbia, not dated.

- Stojanović, B.; Martinović, U. Beograd 1945–1975. Urbanizam. Arhitektura [Belgrade 1945–1975. Urbanism. Architecture]; Niro Tehnička Knjiga: Belgrade, Serbia, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Uslovi konkursa [Conditions of the Competition]. Tehnika [Technology] 1946, 11–12, 339–342. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrović, N. Obnova i Izgradnja Beograda. Konture budućeg Grada [Reconstruction and Construction of Belgrade. Contours of the Future City]; Urbanistički Institut NRS: Belgrade, Serbia, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Blagojević, L.J. The residence as a decisive factor: Modern housing in the central zone of New Belgrade. Architektúra & Urbanizmus [Architecture and Urbanism] 2012, 3–4, 228–249. [Google Scholar]

- Ilić, L. Uz izgradnju Novog Beograda [On the Construction of New Belgrade]. Arhitektura [Architecture] 1948, 8–10, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mišić, B. Palata Saveznog izvršnog veća u Novom Beogradu [The Building of the Federal Executive Council in New Belgrade]. Nasleđe [Heritage] 2007, 8, 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Minić, O. Moderna galerija u Beogradu [A modern gallery in Belgrade]. Arhitektura urbanizam [Arch. Urban.] 1962, 16, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Perović, M.; Tomić, V. Elaborat o lokaciji i urbanističko-tehničkim uslovima za Muzej revolucije u bloku 13 na Novom Beogradu [Study on Location and Urbanistic-Technical Conditions for (the Construction of) the Museum of the Revolution in Block 13 in New Belgrade]; Zavod za planiranje razvoja grada Beograda [The Institute for the Developmental Planning of the City of Belgrade]: Belgrade, Serbia, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Vesković, I. Park prijateljstva u Novom Beogradu [The Park of Friendship in Novi Beograd (New Belgrade)]. Nasleđe [Heritage] 2011, 12, 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Generalni urbanistički plan Beograda do 2000 [General Urban Plan of Belgrade to 2000]; Urban Planning Institute of Belgrade: Belgrade, Serbia, 1972.

- Generalni plan Beograda do 2010 [General Plan of Belgrade to 2010]. Službeni list grada Beograda [Official Gazette of the City of Belgrade] 2003, 27, 901–1080.

- Simić, I.; Stupar, A.; Djokić, V. Building the Green Infrastructure of Belgrade: The Importance of Community Greening. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Usce Park to Have Seven Zones—We Present Conceptual Design of Belgrade‘s Green Oasis. eKapija. 16 March 2017. Available online: https://www.ekapija.com/en/real-estate/1699074/KZIN-BUP/usce-park-to-have-seven-zones-we-present-conceptual-design-of-belgrades (accessed on 25 March 2017).

- Generalni urbanistički plan Beograda [General Urban Plan for Belgrade]. Službeni list grada Beograda [Official Gazette of the City of Belgrade] 2016, 60, 1–106.

- Grubbauer, M.; Čamprag, N. Urban Megaprojects, Nation-State Politics and Regulatory Capitalism in Central and Eastern Europe: The Belgrade Waterfront Project. Urban Stud. 2019, 649–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahm, P. In Architecture, Precisely. In Precisions: Architecture between Sciences and the Arts; Moravánszky, A., Fischer, O.W., Eds.; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 166–195. [Google Scholar]

- Blagojević, L.J.; Ćorović, D. Klimatske promene i estetika savremene arhitekture [Climate change and contemporary architecture aesthetics]. In Uticaj klimatskih promena na planiranje i projektovanje [The Impact of Climate Change on Planning and Design]; Djokić, V., Lazović, Z., Eds.; Univerzitet u Beogradu–Arhitektonski fakultet: Belgrade, Serbia, 2011; pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Vasiljević, N.; Radić, B.; Šljukić, B.; Gavrilović, S.; Medarević, M.; Ristić, R. The concept of green infrastructure and urban landscape planning: A challenge for urban forestry planning in Belgrade, Serbia. iForest-Biogeosci. For. 2018, 4, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Milinković, M.; Ćorović, D.; Vuksanović-Macura, Z. Historical Enquiry as a Critical Method in Urban Riverscape Revisions: The Case of Belgrade’s Confluence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041177

Milinković M, Ćorović D, Vuksanović-Macura Z. Historical Enquiry as a Critical Method in Urban Riverscape Revisions: The Case of Belgrade’s Confluence. Sustainability. 2019; 11(4):1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041177

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilinković, Marija, Dragana Ćorović, and Zlata Vuksanović-Macura. 2019. "Historical Enquiry as a Critical Method in Urban Riverscape Revisions: The Case of Belgrade’s Confluence" Sustainability 11, no. 4: 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041177

APA StyleMilinković, M., Ćorović, D., & Vuksanović-Macura, Z. (2019). Historical Enquiry as a Critical Method in Urban Riverscape Revisions: The Case of Belgrade’s Confluence. Sustainability, 11(4), 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041177