1. Introduction

The global corporate responsibility landscape has been and continues to be the subject of profound and wide-ranging changes. Alongside increasing globalization, there is a continuing global dissemination of corporate responsibility tools, practices, and initiatives [

1]. Increasing public awareness of grand challenges such as climate change, biodiversity, corruption, or poverty alleviation is continuing to push social performance further up corporate agendas. As a result, sustainability reporting, eco- and fair trade-labels, or the implementation of standardized social and environmental management systems have become mainstream practices for large multinational companies (MNCs) in particular.

Further, corporate responsibility and corporate sustainability are no longer exclusively the concern of highly visible MNCs based in developed countries. While firms in developing countries have long been seen as lagging behind their developed country counterparts in social responsibility issues, this picture of a fairly neat “North-South divide” [

2] in terms of corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices is changing rapidly. The dramatic rise of emerging economies—and with it, the rise of emerging economy firms—challenges the long-standing assumption that the major business-society fault lines in developing countries lie between northern MNCs and poor, powerless communities in which these companies are operating, or from which they are sourcing. For example, in 2017, the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) economies alone accounted for 413 of the 2000 largest firms worldwide [

3]. Likewise, the number of people constituting the global ‘working middle-class’ has risen threefold between 1991 and 2015 [

4]. Smaller developing country firms are increasingly likely to be part of global value chains led by large MNCs [

5], and thus increasingly exposed to social and environmental responsibility pressures stemming from developed country consumer markets and the ever-expanding range of CSR tools and initiatives.

Many emerging economies have quickly experienced dramatic changes in business-society relations, and Myanmar is a particularly poignant example. Myanmar was almost entirely cut off from the international community before its regime opened up the country’s economy in 2012. Myanmar is therefore one of the newest additions to the international CSR community, and the CSR efforts of its domestic firms could be expected to lag far behind those of their international developing country peers. International CSR infrastructures and knowledge bases aim to help close this gap through the dissemination of new information technologies and application of more well-established CSR practices. But unlike other developing countries, Myanmar has not been subject to a buildup of institutional CSR pressures over time, including initiatives such as the International Organization for Standardization standard ISO 26000. Instead, Myanmar was exposed virtually overnight to a multitude of partially competing CSR discourses linked to different actors and initiatives. Therefore, the question arises, which of these discourses have gained more traction, and how have they shaped concepts and practices of corporate responsibility within Myanmar?

In this paper, we explore the views of domestic and international firms operating in Myanmar in relation to CSR and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). We present the results of a large-scale survey of 1316 corporate practitioners in Myanmar, comprising individuals in both domestic firms and international firms operating in the country. We (1) investigate levels of awareness of CSR and the SDGs, and (2) explore which dimensions of these two conceptual areas are prioritized by domestic and international firms, respectively. Our findings reveal that contrary to our expectations, awareness levels of CSR and the SDGs are not lower among domestic Myanmar firms when compared to their international peers. Crucially, recall of the SDGs is shown to be even higher among domestic firms when compared to their international counterparts. Further, domestic Myanmar firms appear to find it easier to frame their non-financial responsibilities in terms of the newer, more problem-focused set of SDGs rather than the internationally more well-established, but arguably more process-oriented CSR toolset.

Whilst our study provides some indication that domestic firms adapt and “translate” CSR to make it relevant to their own local contexts, resulting in unique Myanmar-specific manifestations of CSR [

6], the extraordinarily high levels of CSR and SDG awareness among domestic firms in Myanmar carry significant implications for both policymakers and corporate practitioners. Our study makes two main contributions to the extant literature. First, we add to the emerging body of literature focusing on CSR and corporate sustainability in non-Western contexts by providing a Myanmar perspective. Second, we shed light on the extent to which recent attempts to promote awareness of the SDGs have fared in a still-fragile, developing economy such as Myanmar.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we introduce Myanmar as the research setting of our study, with particular emphasis on Myanmar’s evolving socio-economic context since the 2012 economic opening. Building on institutional theory and the National Business Systems (NBS) perspective [

7], we then develop a set of hypotheses concerning similarities and differences in the ways in which domestic and international market participants in Myanmar view their companies’ CSR engagement, as well as activities in relation to the SDGs. Following that, we justify and describe our research methods and sample. Subsequently, we present key findings of our analysis and discuss their relevance in light of the extant literature. We conclude by sketching out opportunities for future research based on our study.

2. Economic Opening for Development in Myanmar

We first offer a brief description of the Myanmar business setting (for a more comprehensive discussion of this section, and Myanmar’s unique role in business-conflict dynamics, see [

8]). Myanmar’s celebrated economic opening has led to rapid but uneven economic expansion in a still-fragile society, with positive and negative social consequences. Foreign firms have dramatically expanded investment in nearly all sectors of Myanmar, growing foreign direct investment ten-fold since 2011 [

9]. These ventures are coupled with a similar increase of international economic development projects, which aim to help support economic growth that is presumed to solidify democracy. These dynamics provide an opportunity to study how a rapid influx of new investments and new ideas can impact perceptions of business responsibility in a fragile country setting.

Ranking in the bottom 5% of 189 countries surveyed by the World Bank [

10] in most metrics for ease of doing business, Myanmar’s business environment remains permeated by endemic corruption [

11]. A common assumption was that due to Myanmar’s closed economy, national firms had less sophisticated understandings of the contemporary roles and responsibilities of business in society. To address this, multilateral institutions have prioritized regulation overhaul in an attempt to modernize the playing field, particularly in reform of banking and finance through including contractual certainty, financial fairness, and freedom from corruption and extortion to increase transparency, efficiency, and state stability [

12].

In response, Myanmar’s economy has indeed grown by about 8% per year since 2012 [

9], which by some indicators can be a positive proxy for societal development. However, in Myanmar this growth has increased inequality. Gains have primarily benefitted elite groups that were in power before the country’s opening, as most new initiatives require local partners who hold high-level roles in Myanmar’s political-military nexus. A mandatory joint ventureship structure in Myanmar cements existing economic hierarchies, and blurs the lines of what constitutes an expected social impact by a foreign versus domestic company [

13]. While opening brought optimism that trade and growth would lift Myanmar’s poorest, Myanmar’s military junta took this path not to succumb to foreign pressure, but to consolidate military rule of the country’s power centers [

14].

Of deeper concern, after the opening Myanmar’s military conducted an ethnic cleansing of two million Rohingya Muslims in western Rakhine state, precisely the type of authoritarian action that economic opening was promised to temper. Today, 700,000 Rohingya are refugees in neighboring India and Bangladesh, and another 100,000 persons are in internally displaced persons camps [

15]. The United Nations Human Rights Council proposes that military leaders be tried for genocide, and that one Northern MNC in particular (Facebook) was a key facilitator of the violence by amplifying messages of hatred by Burmese generals, and not acting when confronted with this evidence [

16]. Instead of prioritizing reparation of the Rohingya, the government is instead encouraging Myanmar conglomerates to first pursue new business opportunities in Rakhine as a substitute for development [

17] and as a CSR activity in and of itself.

Myanmar’s neoliberal economic reform model has exacerbated socio-economic grievances. While economic incentives can be beneficial to society [

18], in Myanmar, reforms have prioritized economic elements of development. This corporate peace [

19] entrenched power within a military-political elite at the expense of democracy [

20]. Likewise, Chinese investment in the period preceding the opening, which enriched the military junta but offered little development benefit due to distorted incentives structures, rewarding the very conglomerates that prospered during military rule due to their entrenched cronyism [

21]. The reforms “created significant inequalities and environmental and social challenges, and thus, (an unsustainable) developmental trend” ([

22], p. 340); a trend exacerbated by a focus on large-scale investment in Yangon as a new ‘Smart City’ without comparative development-based investments elsewhere in the country [

23]. Efforts by international actors to expand the existing model of economic liberalization has been interpreted by Burmese officials as tacit approval for ethnic discrimination [

24].

While we can see links between business and conflict in Myanmar, it remains unclear as to what degree businesses attempt to make a positive difference, and the variations of such activities across the business landscape. Outside pushes for firms to contribute to socio-economic development in Myanmar have grown. International NGOs, the UN, and MNCs have all developed projects that publicly aim to support peace, human rights, and development through the private sector. These initiatives stress economic growth, improvement of disadvantaged areas, and importing international regulatory business norms. Some firms have gone further, as when Myanmar head of Norwegian mobile firm Telenor Petter Furberg [

25] proclaimed that their work in creating mobile infrastructure with the support of insurgent groups should be rewarded as nation-building. Such actors see their roles as being at the win-win intersection of social development and business risk mitigation/aversion, even as local government and business actors are less inclined to see such initiatives as beneficial [

26].

The belief that foreign firms can offer moral or practical guidance on CSR is contested. For example, most foreign firms in Myanmar have CSR policies that in principle would exclude their operation in the country for human rights reasons. However, such firms typically argue that they can be a “force for good” in such situations [

27]. It aligns with the assumption that foreign firms can be prescriptive entities in the developing world, a reputable source of knowledge for local firms on societal best practice. To wit, a common claim by proponents of MNC engagement with repressive regimes is that, should they pull out over human rights, their presence would simply be filled by a Global South firm that would not have such concerns [

28]. Yet as conflict and rights abuses continue in Myanmar, nearly all foreign firms have elected to maintain their presence, in many cases partnering with a government that is committing well-documented rights violations.

This puzzle highlights two key assumptions that are worth exploring. First, that foreign firms would be the primary driving forces in developing business as a force for social good in fragile contexts like Myanmar, both through their own actions and/or by applying pressure upon their domestic partners. Second, that companies based in countries where business-development interactions are considered to be less sophisticated, such as in Myanmar, are typically assumed to have less prolific CSR profiles than their more advanced corporate counterparts from the Global North (cf. [

29]). These assumptions form the starting point of our theoretical exploration.

3. Theory Development

Here we compare the CSR activities and perceptions of domestic and multinational firms operating in Myanmar through the analytical lens of institutional theory [

30,

31,

32], and the National Business Systems (NBS) perspective [

7,

33,

34]. Institutionalism has become a dominant strand within organization theory and builds on the assumption that institutions, defined as ‘‘shared rules and typifications that identify categories of social actors and their appropriate activities or relationships’’ ([

35], p. 96), help shape organizational action. This also holds true for corporate social responsibility [

36,

37] where the specific context a company operates in generally determines what corporate responsibility means and entails.

Historically, mainstream CSR can be traced back to its Anglo-American origins [

38]. More recently, however, it has become more global in scope: emerging economy firms are increasingly expected to address the social and environmental impacts of their operations [

39,

40]. From an institutional perspective, different types of isomorphic pressures can be identified that drive the dissemination of CSR practices into developing country contexts. Coercive pressures may for instance stem from focal firms in a supply chain [

41], international NGOs [

42,

43], standard-setting bodies [

44], or also national governments [

45] to force companies to voluntarily adopt CSR practices. Normative isomorphism can be based on the activities of multi-stakeholder initiatives such as the Global Reporting Initiative [

46] or the UN Global Compact (UNGC) [

47,

48], promoting more responsible and/or sustainable practices and the uptake of specific tools that should allow companies to do so. As of 22 January 2019, 164 corporate participants have signed up to the national UNGC network in Myanmar, for example, surpassing corporate membership in countries such as Turkey or Finland [

49]. Finally, mimetic pressures may lead companies to copy the actions of their peers and thus to adopt specific CSR practices [

50].

As a result, the adoption of CSR tools such as standardized environmental management systems [

51], corporate codes of conduct [

52], and social and environmental reporting [

46], has proliferated within non-Western contexts. Yet, the uptake of CSR among developing country firms has been slower and less intensive when compared to their Northern counterparts, possibly even constituting a “North-South divide” [

2]. In many ways, research helping us to understand the dynamics of CSR in developing country contexts has equally been lagging, and only recently gained traction (for an overview of recent studies, see [

1]). Whilst few of these studies have specifically focused on CSR in Myanmar (for exceptions see [

53,

54]), this emerging literature on CSR in developing countries can nevertheless serve to underpin this current study.

One theoretical lens that has frequently been applied in this body of literature is the NBS perspective [

1,

7,

55]. For our analysis, NBS is a useful conceptual lens to identify generic country-level factors that are likely to support or hinder the adoption of CSR activities in Myanmar. Regarding CSR, factors that have been found to hinder its dissemination include low levels of economic development and the absence of a financially and politically independent middle-class that could drive demand for CSR practices [

56], widespread implementation deficits in relation to social and environmental governance [

57], a lack of awareness with regard to underlying social and environmental problems, or dominant country-level cultural [

58] or religious norms [

1]. Given the nature of the Myanmar business environment, characterized by decades of isolation and little exposure to the international business community before 2012, we expect domestic companies to be less exposed to pressures to adopt CSR practices when compared to MNCs. We therefore hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1. MNCs will be more likely to engage in CSR than domestic firms in the Myanmar context.

However, whilst CSR is commonly used as an umbrella term for a wide range of social, environmental, and economic activities [

59], only some types of these feature prominently in the mainstream global CSR agenda. In other words, CSR as commonly conceptualized, can be seen as one specific—albeit, not the only possible—manifestation of corporate responsibility. For example, the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have recently emerged as an influential agenda in corporate responsibility [

60,

61]. As a direct successor to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the SDGs aim to promote more sustainable and inclusive forms of development, bridging the two discourses of environmental protection and international development. They comprise a list of 17 goals and define 169 targets, (mostly) to be reached by the year 2030, that promote more sustainable forms of development. The SDGs thus continue the paradigm shift towards a more partnership-oriented and managerial approach to development that had been started with the MDGs [

62].

Reception of the SDGs has been mixed among policymakers, the academic community, and the general public [

63]. Whilst, like their predecessor, the SDGs were developed from within the UN institutional structures, the process by which the goals and targets were decided upon was highly inclusive [

64]. Consequently, the SDGs appear to lack focus when compared to the MDGs, given the large number of goals and targets to be achieved [

65]. Still, the SDGs have become an important multi-lateral framework for firms to operationalize their social works, and at least 86% of the world’s largest 500 firms have made stated commitments to support the SDGs in their operations [

66]. Further, buy-in across the global South is high [

67]. Ultimately, despite its flaws, the SDG agenda will shape international policy efforts over the next decade.

Business is one of a range of different actors that are expected to contribute to the SDGs [

61]. Conceptually, there are clear links between the SDGs and CSR theorizing, and the private sector can contribute to the SDGs in a range of goals including SDG 1 (Poverty alleviation), SDG 8 (Decent work and economic growth), SDG 9 (Industry, innovation and infrastructure), and SDG 13 (Climate action) [

68]. However, the impact of such activity is not yet clear. If CSR engagement by firms from the global South is indeed under-researched [

69], then this likely also holds true for the SDGs [

68]. Building on our above argument regarding the more mature state of large companies’ CSR programs, we would also expect them to be more active in terms of addressing SDGs than their domestic counterparts. We therefore hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2. MNCs operating in Myanmar will be more likely to engage with the SDGs than domestic Myanmar firms.

Beyond the

extent to which CSR is adopted by developing country firms, previous studies have also shown that the

nature of CSR activities might be different from what is typically found in developed countries [

1]. Rather than a unidirectional dissemination of different CSR practices from developed to developing country contexts, we often see a more complex adaptation and “translation” processes resulting in country-specific manifestations of CSR based on the interplay of a wide range of actors [

6]. Again, taking an NBS perspective in that national institutional contexts to some extent shape the way in which companies approach CSR [

1], we would expect domestic firms to differ from their international peers in relation to the nature of their CSR engagement.

Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in particular could be expected to function differently in this regard. It has long been acknowledged that rather than treating SMEs like “little big companies” [

70], they have unique characteristics and an oftentimes different nature of CSR engagement [

71,

72]. This point is particularly salient in developing country contexts where SMEs typically constitute a far greater share of the economy [

5]. Many conventional CSR practices appear to be geared specifically towards large MNCs operating in foreign contexts rather than their domestic peers. For example, this point has been made in the context of corporate sustainability reporting [

73] or external communication more generally [

74].

However, the absence of mainstream CSR tools such as corporate sustainability reporting, standardized management systems, or corporate codes of conduct does not necessarily indicate the absence of corporate responsibility by a given firm. For example, responsibility can be exercised on the basis of other, commonly more informal approaches, as in values-based approaches of owner-manager firms [

71]. Likewise, since SMEs typically operate in one region, they are usually more deeply embedded into one specific regulatory and societal context, whereas MNCs can often be characterized by more complex yet indirect relationships with local communities. This more informal character of CSR and the more important role of personal relationships within the community may explain why corporate philanthropy has repeatedly been highlighted as widespread practice in developing country contexts [

37,

75]. We thus hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3a. Domestic firms in the Myanmar context engaging in CSR will be more likely to prioritize philanthropic activities than foreign firms.

A bias towards larger companies has also been found with regard to standardized environmental management systems such as ISO 14001 [

76]. Various studies have found a link between company size and corporate environmental performance [

77], not least based on economies of scale and the argument that large MNCs have more slack resources at their disposal to address environmental challenges [

78]. As the Myanmar economy only recently opened up for international trade, domestic firms arguably are only now starting to be exposed to the relatively mature environmental management toolset that has been applied for a much longer time-span by their international peers. This leads us to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3b. Domestic firms in the Myanmar context engaging in CSR will be less likely to prioritize activities aimed at the natural environment than foreign firms.

Differences between (smaller) domestic firms and (larger) MNCs also extend to the wider roles and responsibilities of business in society. Recent conceptualizations such as the extended view of corporate citizenship [

79], political CSR [

80] and Creating Shared Value [

81], all share that companies are increasingly expected to assume explicitly political roles to support broader societal objectives. Large MNCs in particular are encouraged not only to be concerned with their narrow sphere of responsibility, but their wider sphere of influence [

80]. Both ethical and financial arguments have been provided to promote the involvement of large MNCs in the business and human rights agenda [

82]. In Myanmar, the clearest and most direct such action lies in human rights, including advocating for marginalized communities including but not limited to the Rohingya, due process, and other democratic processes. We thus hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3c. Domestic firms in the Myanmar context engaging in CSR will be less likely to prioritize human rights-related activities than foreign firms.

Hypothesis 3d. Domestic firms in the Myanmar context engaging in CSR will be less likely to prioritize political CSR activities than foreign firms.

4. Materials and Methods

We tested our set of hypotheses with a smartphone-based survey of 1316 corporate practitioners operating in Myanmar, implemented by the expert survey firm RIWI. A survey instrument was deemed as particularly appropriate given the industry structure in Myanmar, with a dominance of small and medium-sized firms that tend not to maintain more formalized communication channels such as corporate annual reports or corporate websites. RIWI applied a Random Domain Intercept Technology [

83] in order to minimize sampling bias and aim at a representative sample of the population of corporate practitioners in the Myanmar context. This research technique is a well-established big data approach that has been applied in a variety of different contexts, ranging from surveys on mental health stigma [

84] to opinion-mining of citizen-driven accountability [

85]. Specifically, “RIWI’s proprietary Random Domain Intercept Technology (RDIT) allows for the rapid capture of large samples of broad, truly randomized opinion data, or to expose randomized populations to targeted communications on an ongoing basis in all countries. RDIT intercepts random web users who are surfing online by typing directly into the URL bar. When these users make data input errors by typing in websites that no longer exist, or by mistypes on non-trademarked websites that RIWI owns or controls, RIWI invites these random, non-incentivized users, filtered through a series of proprietary algorithms, to participate in a language-appropriate survey, or are directly exposed to a targeted communication. RIWI automatically geo-targets respondents by country, region, state, city, sub-city, district, or in circles using latitude and longitude coordinates and a radius. RDIT is device-agnostic, rendering with responsive design and working on all web-enabled devices. RDIT cannot be blocked by state surveillance or internet control. RDIT evades firewalls in ‘opaque markets’ by operating on hundreds of rotating domains simultaneously. States can easily shut down individual websites, but they cannot shut down ephermal, scattered, and changing domains [

86].”

While selection bias of a sample weighted towards the more affluent and/or technologically engaged would normally be of concern (Myanmar has less than 50% smartphone penetration, but this statistic is growing rapidly), for the purposes of our study we assumed that any business practitioner with the capability to have societal impact would have such access. This format thus carried a positive selection benefit for the individuals that we wished to reach. The survey was conducted January to February 2018 in Myanmar in both Burmese and English, and was geo-coded to the city level of analysis. We asked 15 closed questions related to our above hypotheses, with three possible additional questions based upon responses. Due to the limitations of the survey format, we restricted our questions to 8 of the 17 SDGs: Goals 1, 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 13, and 16, also providing an “other” option to respondents. We selected these eight based on previous pilot research suggesting these as the most important for firms working in Myanmar [

8,

87].

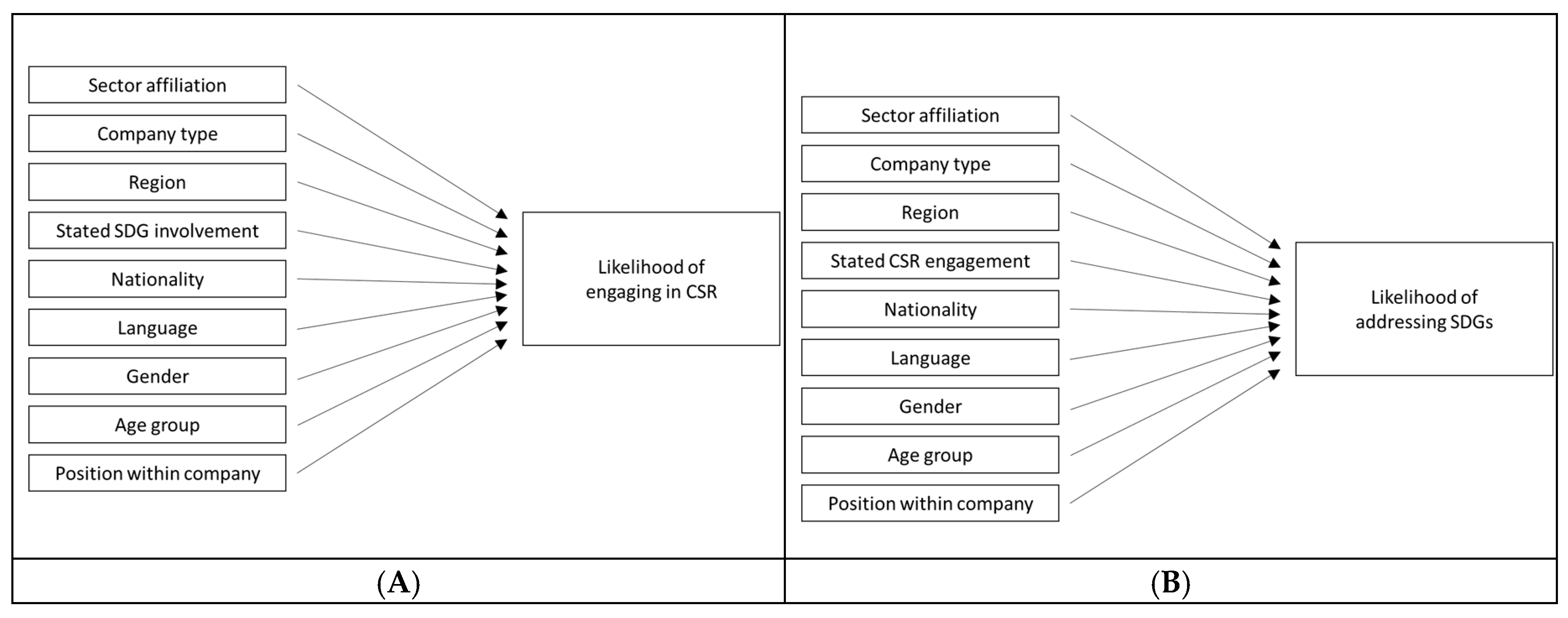

To test hypotheses 1 and 2, we constructed two models focusing on the respondent companies’ likelihood of engaging in CSR (Model A) and addressing any of the SDGs (Model B), respectively (

Figure 1). In both cases, we coded responses as a binary dependent variable (yes = 1; no = 0). Given the dichotomous nature of our dependent variables, we performed binary logistic regression analyses to identify factors that influenced the likelihood of companies to engage with CSR or to address the SDGs. One common limitation of survey-based research is the extent to which non-respondents may have responded differently from those who were willing to participate in our survey [

88]. For this reason, we conducted independent sample T-tests on our two dependent variables to test for statistical differences between the first three quarters and the final quartile of our respondents. This approach is based on the assumption that responses of the final quartile are similar to those of non-respondents, and has repeatedly been adopted in research into corporate responsibility (e.g., [

44]). Results of the independent T-tests suggest that there is no significant non-response bias.

A number of independent variables were included in both models. We distinguished between domestic and international firms operating in Myanmar on the basis of a binary variable. Furthermore, dummy variables were created for the six different sectors included in our sample (retail, manufacturing, agriculture, banking, extractives, technology, and telecommunications) as well as for age groups and position within the company (entry-level, mid-level, manager, director/owner). Given the complexity of ownership structures found in Myanmar—with joint ventures between domestic and international partners as a dominant of the economy—the anonymous nature of the survey made it difficult to reliably establish the country of origin for the international companies the respondents are based in. However, we created dummy variables for the different nationalities of respondents (Myanmar, Southeast Asia except Myanmar, India, China, Europe, North America, and other countries) which should be able to serve as a rough proxy in this context. Likewise, the nature of our sample made it difficult to establish firm size, especially given the difficulties associated with different size measurements in predicting specific firm-level outcomes [

89]. However, given the large sample size (n = 1316) and the industry structure of Myanmar, with an overwhelming majority of SMEs, it is safe to assume that domestic firms were smaller than their multinational peers included in the sample. Finally, we also controlled for gender and language of respondents (Burmese, English), the location of operations within Myanmar (Yangon region versus other regions) and whether the respondent’s company addressed any of the SDGs (in Model A focusing on CSR) or was engaged in CSR (in Model B focusing on the SDGs). Variance inflation factor (VIF) values for all variables included in the two models remain below 1.6 and thus also well below the recommended cut-off value of 10 [

90], suggesting that no multicollinearity issues affected our results.

Initially, we also considered binary regression analysis to test hypotheses 3a–d, i.e., prioritization of different CSR dimensions among corporate practitioners. However, given that (a) model fit measured by Chi-squared values turned out to be insignificant when using individual CSR dimensions as dependent variables turned out as insignificant; (b) pseudo R-squared values did not increase throughout when independent variables were entered stepwise into the model [

91]; and (c) given the largely homogeneous patterns in relation to our set of independent variables when examining the likelihood of addressing CSR more generally, we decided that the most appropriate technique to test hypotheses 3a–d was to perform Chi-squared tests. We used four different CSR dimensions as our dependent variables (philanthropy, environmental sustainability, human rights engagement and political CSR); and the distinction between domestic and international firms as our independent variable for the Chi-squared tests.

As with any corporate responsibility-related survey, social desirability response bias [

92] may have influenced the responses we collected. However, we do not see any apparent reason why social desirability response bias may have influenced specific parts of our sample more than others, for example in relation to company size, sector affiliation, or country of origin. In addition, we are aware that our survey captures CSR- and SDG-related perceptions of corporate practitioners rather than more directly exploring corporate practices in this context. This is not only a common limitation in survey-based CSR research, but it also applies to e.g., analyses of corporate codes of conduct [

52], corporate sustainability reports [

46], and adoption rates of social and environmental management systems [

41] where the implementation of any process could be done in a substantive or symbolic manner [

44]. Thus, it would not necessarily shed light on actual CSR performance of the firm.

5. Results and Discussion

Table 1 summarizes descriptive statistics of our sample. Overall, the sample consists of 1316 respondents, 868 of which answered questions linked to the SDGs. This difference is due to the fact that questions were answered sequentially, with the block of SDG-related questions following those focusing on CSR. On average, 66 per cent of respondents stated that their firm engaged in some sort of CSR activity. A slightly smaller share (60%) of the respondents were aware of their company addressing any of the SDGs. Relatively subtle differences can be observed in relation to CSR and SDGs when comparing coverage in different sectors, with regard to different positions within the company, age group, or gender. Notable differences include that retail firms appear less likely to address any of the SDGs when compared to other sectors; and that respondents from domestic firms show higher awareness of SDG engagement than their international peers.

The results of the two logistic regression analyses are presented in in

Table 2 and

Table 3, respectively.

Table 2 focuses on the firms’ likelihood of engaging in CSR, whereas

Table 3 shows their likelihood of addressing any of the SDGs as part of their operations. Pseudo R-squared values (Hosmer & Lemeshow) are quite low with values of 0.046 (CSR) and 0.070 (SDGs). However, model fit can be difficult to interpret in logistic regression models [

93]. Model fit expressed as Chi-squared is significant both in the case of CSR (χ

2(23) = 46.99,

p < 0.001) and SDGs (χ

2(23) = 55.320,

p < 0.001), and in both cases pseudo R-squared values increase throughout when independent variables are entered stepwise into the model [

91]. Therefore, model fit appears satisfactory in both cases.

Table 2 focuses on the extent to which the respondents state that their companies engage in CSR. We can see that overall, few clear patterns can be identified. Male respondents are more likely to state that their company engages in CSR, as do respondents who have filled in the English language version of the survey. Unsurprisingly, respondents who are aware of their company addressing any of the SDGs are also more likely to state that the company is engaged in some sort of CSR activity. However, no significant relationships can be observed with regard to sector affiliation, levels of experience, age, or nationality of the respondents. With regard to the latter, it is furthermore worth noting that B(SE) values are positive (but insignificant) for all countries and regions of origin except Europe/North America when compared to the control group Myanmar. Finally, no significant difference emerges between domestic firms and MNCs regarding their stated CSR engagement. As a result, hypothesis 1 needs to be rejected.

Logistic regression results for the likelihood of addressing the SDGs are displayed in

Table 3. Here, the pseudo R-squared value is slightly higher than in the previous model. Retail firms are significantly less likely to be associated with SDG engagement when compared to the control group Technology/Telecommunications. Contrary to our expectations, domestic firms are significantly more likely to address any of the SDGs than MNCs. Therefore, hypothesis 2 is rejected. While respondents in the age group 45 to 54 are less likely to find their company to address the SDGs, no notable differences emerge in relation to the respondents’ position within the company. Again, nationality does not appear to impact the likelihood of a company addressing the SDGs. The direction of B(SE) values is less consistent when compared to CSR engagement, with Chinese, Indian, and European/North American respondents showing a positive B(SE) value when compared to the control group Myanmar.

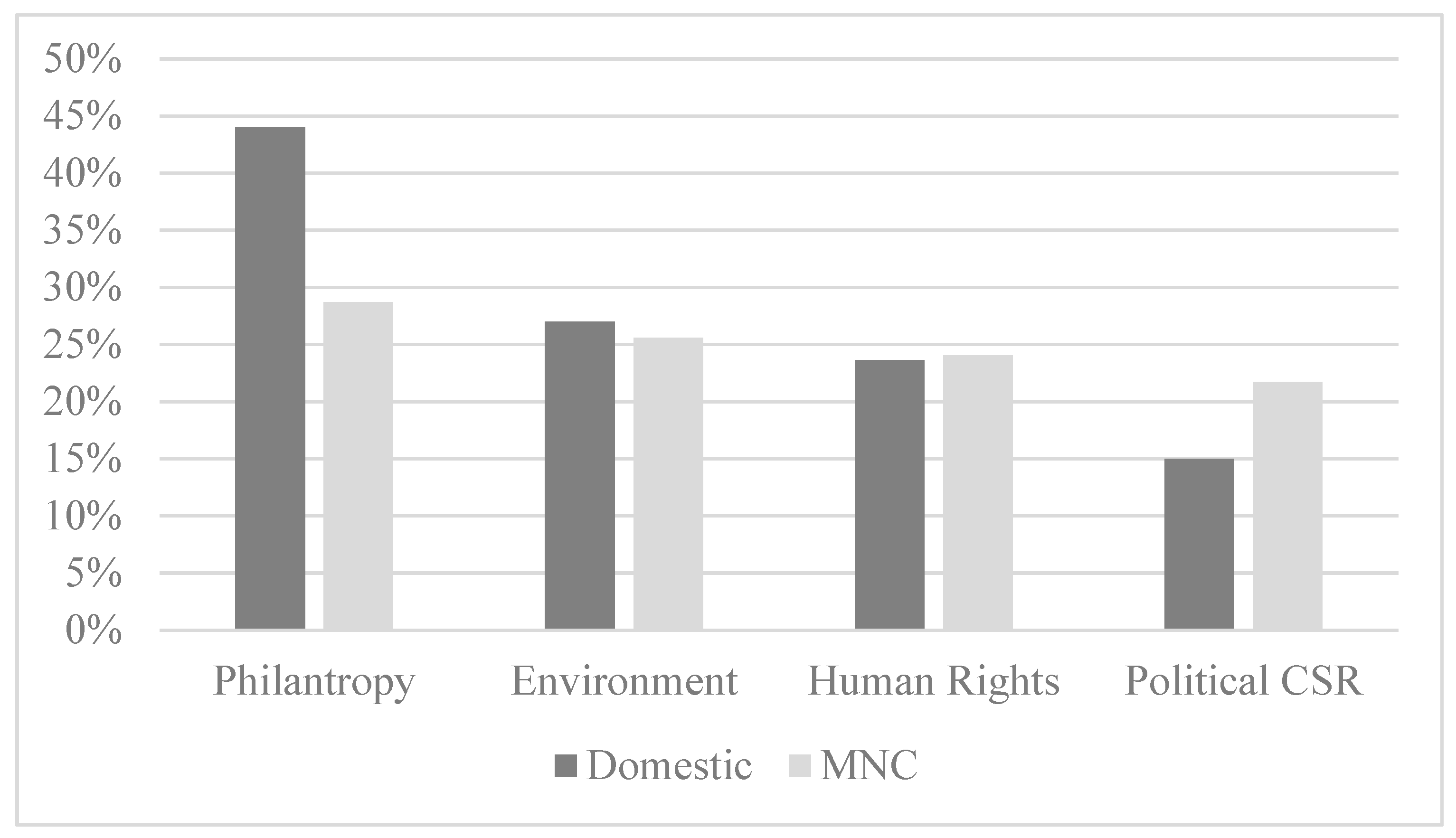

Figure 2 summarizes the likelihood of respondents based in domestic and multinational firms to engage in different CSR dimensions. Whilst domestic firms clearly emphasize philanthropy over other CSR dimensions, no such clear prioritization of any specific dimension can be identified for MNCs. Corresponding Chi-Square tests show that there was a significant association between organization type and the likelihood of engaging in corporate philanthropy (

χ2 (1) = 10.60,

p < 0.001). Based on the odds ratio, domestic firms were 1.95 times more likely to engage in corporate philanthropy. No significant relationships can be identified in the case of environmental sustainability or human rights-related CSR. However, a significant association also emerges between organization type and political CSR (

χ2 (1) = 3.70,

p < 0.05). Looking at the odds ratio, we find that MNCs were 1.57 times more likely to engage in political CSR than domestic firms were. With regard to individual SDGs (

Figure 3), a significant association can only be identified between organization type and SDG 16 (

χ2 (1) = 4.05,

p < 0.05). Here, the odds ratio indicates that MNCs were 2.03 times more likely to address SDG 16. In summary, we find partial support for our hypotheses 3a–3d. Hypotheses 3b and 3c need to be rejected, whereas hypotheses 3a and 3d are supported.

Looking at the main patterns emerging from our analysis, the most striking finding is arguably one that we do not observe, i.e., differences in CSR/SDG adoption between domestic and international firms. Rather than reflecting a North-South divide [

2], awareness levels of domestic Myanmar firms by and large have shown to be at the same level as those of their multinational peers. Evaluating actual corporate social performance dimensions [

94] is beyond the scope of this study and many of the surveyed companies may in fact choose to commit to CSR in a more symbolic rather than substantive manner [

44]. That said, it is nonetheless surprising that similar numbers of—typically smaller—domestic Myanmar firms commit to CSR when compared to their—typically larger—international peers, in particular considering Myanmar’s very recent economic opening. Joint venture relationships with international partner companies and initiatives such as the UN Global Compact network [

48] may have supported this process, promoting awareness of CSR and related concepts.

At the same time, this might not simply be a matter of domestic firms adopting CSR practices along the lines of their international peers. CSR practices and understanding appear to differ between domestic and multinational companies in the Myanmar context. Most notably, respondents from domestic firms prioritize philanthropic activities under the umbrella of CSR, whereas those of multinational firms place more emphasis on corporate political activities. In other words, domestic firms may adapt and “translate” CSR and make it relevant to their own local contexts, which results in unique country-specific manifestations of CSR [

6,

95]. Most surprisingly, and contrary to our hypothesis 2, awareness of the SDG agenda seems to be higher among domestic firms when compared to their international peers. In other words, domestic firms appear to find it easier to frame their social good activities in terms of the SDGs than multinationals. As argued elsewhere, buy-in into the SDG agenda has been particularly high across the global South [

67], which might help explain the high awareness levels among domestic Myanmar firms.

To a certain extent, the popularity of the SDGs might be explained by the significant awareness activities of international development actors operating in the country. However, other factors may have contributed to the relative success of the SDGs—vis-à-vis CSR—among Myanmar firms. The issue orientation of the SDGs might lend itself to the realities of smaller firms when compared to the process orientation of many widespread CSR tools that have often been geared towards very large multinational companies [

5]. Furthermore, the SDGs explicitly include core business dimensions (as, for example, SDG 8 “Decent work and economic growth” [

66]), whereas CSR has long been criticized for its perceived lack of practical relevance, often being detached from a company’s core business activities [

81,

94]. It may not be a coincidence that across our sample, younger respondents are more likely to show awareness of the SDG agenda, whereas older respondents are more likely to frame their companies’ engagement in terms of CSR. Ultimately, domestic firms may find it easier to align their social responsibilities with the SDG agenda rather than adopting the existing CSR toolset.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we presented the results of a large-scale survey of 1316 corporate practitioners in Myanmar. This context provided interesting research opportunities in two different—but complementary—ways. First, the CSR literature has long focused on developed country contexts and firms, but largely ignored emerging and developing country contexts and actors [

69]. This also applies to research focusing on company engagement with the SDGs [

68]. Hence, we are able to add a new perspective to the limited number of existing studies. Second, Myanmar firms had long been operating in isolation from the world economy until its abrupt and rapid economic opening. From a CSR perspective, this also means that Myanmar companies are only now starting to be confronted with expectations regarding their social responsibilities that many international firms have become accustomed to over the last few decades [

48]. Therefore, the research setting provides us with a unique opportunity to examine whether and how domestic Myanmar firms are catching up in terms of meeting stakeholder expectations, and how they frame this type of engagement.

We found that—contrary to our expectations—awareness levels of CSR among domestic Myanmar firms were on par with their international peers. Even more surprisingly, the SDGs appeared to enjoy more widespread awareness among Myanmar firms when compared to multinational firms operating in Myanmar. Whilst there is some indication that CSR implementation of domestic firms follows a different trajectory from those observed in developed economies (for example, a more explicit emphasis on philanthropic or donation-based giving that is in line with what is seen in other developing and emerging economies, see e.g., [

75]), this uptake in terms of awareness of corporate responsibility and sustainability is nevertheless remarkable.

These findings imply that CSR advocacy in the country might need to shift emphasis from awareness-raising towards converting the already relatively high levels of awareness into actual impacts. Furthermore, they underline the need to get a better understanding of the CSR practices that domestic firms are already engaging in. In addition, it appears that the SDGs are likely to be a more effective vehicle to move domestic Myanmar firms towards corporate sustainability than the current set of CSR tools and initiatives. From a corporate perspective, the SDGs also open up opportunities for both domestic developing country firms and Western MNCs. For developing country firms, the SDGs may present opportunities for a fresh start in order to overcome the perceived Northern bias in CSR [

2,

96]. It may also help firms operating in fragile or conflict settings to move towards a CSR agenda that is more cognizant of domestic political calculations and needs, especially as these are the very settings where CSR and SDG engagement by the private sector is most needed [

97,

98]. For Western MNCs with developing country subsidiaries or with values chains extending to developing countries, the SDGs might be more promising vehicles to involve suppliers in these companies’ efforts to improve sustainability performance.

Furthermore, the findings raise questions about the role of ethical decision-making and corporate political activity in relation to the SDGs and CSR. Since 2016, the clearest and most obvious CSR action by a foreign firm would have been to speak out on ethnic cleansing, but none did so. No domestic firms have done such either for fear of punitive consequences. This problem illustrates how CSR in conflict environments is prone to a morality breakdown. Perhaps the SDGs are more attractive to domestic firms precisely because they are more positively-oriented, reducing the potential for hypocrisy in promise and action. By its very nature, CSR implies a moral responsibility to societies, and when choosing to either honour that commitment at the expense of the company’s very existence, the choice becomes easy. Conversely, the very broadness and inclusiveness of the SDGs enables contribution by business without having to face this choice. For example, none of the 169 SDG targets are measured at the participant level, participants can define participation however they choose. This could result in a high percentage of participation by business—as supported by our results—but it may be coming at the expense of depth and impact of said participation.

In the Myanmar case, it is clear that the gaps between foreign and domestic firms about the role of the private sector in social responsibility are not as pronounced as was assumed. Future research should explore differences and similarities further and, to the extent possible, incorporate additional factors such as company size, financial performance, or government and/or stakeholder pressure in order to detect more fine-grained trends and patterns among Myanmar firms. Another promising avenue for future research will also be to move beyond awareness towards the assessment of actual business responsibility practices of firms operating in Myanmar. Thus, another opportunity for future research will also be to move beyond examining the likelihood of adopting CSR practices and to capture the extent to which, as well as the ways in which, CSR practices are carried out, including through the SDGs. Given the scarcity of available sustainability performance information on firms operating in Myanmar, such endeavors are likely to require extensive fieldwork. However, the increasing relevance of sustainability-related business networks in the Myanmar context is likely to facilitate this type of future research.

Taking this research beyond Myanmar to other developing country contexts would help to shed light on the uniqueness of the Myanmar case generally, but more specifically the importance and relevance of the multi-lateral entities that promoted such aims, including in particular the United Nations and UNGC. In other words, international comparative studies will be able to ascertain whether the CSR- and SDG-related patterns spelled out above are specific to the Myanmar case or whether they are indeed a reflection of more recent developments in developing country contexts more generally. These studies could thus help us to better understand the pathways and impact of corporate responsibility knowledge from the developed to developing world, within the developing world, and perhaps most importantly, from the developing to developed world.