Partner Strategic Capabilities for Capturing Value from Sustainability-Focused Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

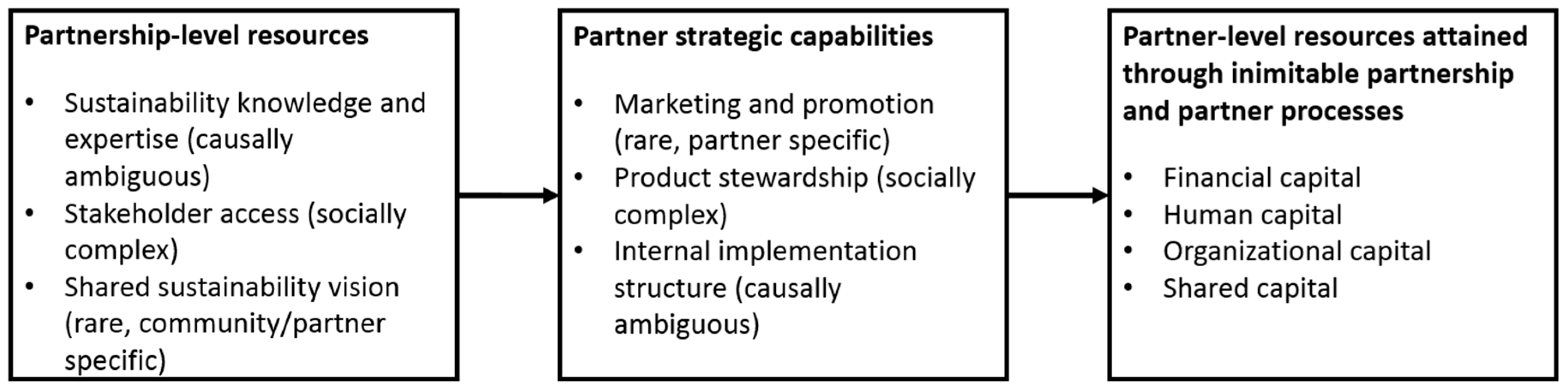

2.1. A Strategic Perspective of Partnership and Partner Outcomes

2.2. Strategic Capabilities for Capturing Value from Partnership-Level Resources

2.2.1. Marketing and Promotion

2.2.2. Product Stewardship

2.2.3. Internal Implementation Structures

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Marketing and Promotion (Marketing)

3.2.2. Product Stewardship (Stewardship)

3.2.3. Internal Implementation Structure (Structure)

3.2.4. Financial Capital (Financial)

3.2.5. Human Capital (Human)

3.2.6. Organizational Capital (Organizational)

3.2.7. Shared Capital (Shared)

3.2.8. Control Variables

3.3. Analysis

4. Results

Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Partner-Level Strategic Capabilities and Resource Outcomes

5.2. Implications for Research

5.3. Implications for Practice

5.4. Areas for Future Research and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reed, A.M.; Reed, D. Partnerships for development: Four models of business involvement. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 90 (Suppl. S1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, J.; Woodhill, A.; Hemmati, M.; Verhoosel, K.; van Vugt, S. The MSP Guide; Practical Action Publishing Ltd.: Warwickshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, A.; Clarke, A.; Huang, L.; Roseland, M.; Seitanidi, M.M. Multi-stakeholder partnerships (SDG# 17) as a means of achieving sustainable communities and cities (SDG# 11). In Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, P. Local Agenda 21: Practical experiences and emerging issues from the South. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1996, 16, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, A.; Clarke, A.; Huang, L. Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainability: Designing decision-making processes for partnership capacity. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, D.; Jotkowitz, B. Local Agenda 21 and barriers to sustainability at the local government level in Victoria, Australia. Aust. Geogr. 2000, 31, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selsky, J.W.; Parker, B. Cross-sector partnerships to address social issues: Challenges to theory and practice. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 849–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, K. The Purist’s Partnership: Debunking the Terminology of Partnerships; The Copenhagen Centre: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003; pp. 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Overseas Development Institute; Foundation for Development Cooperation. Multi Stakeholder Partnerships Issue Paper; Global Knowledge Partnership: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, A. Key structural features for collaborative strategy implementation: A study of sustainable development/Local Agenda 21 collaborations. Manag. Avenir 2011, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.C.; Harvey, J.B.; Aseyev, D.; Alexander, J.A.; Beich, J.; Scanlon, D.P. Approaches to improving healthcare delivery by multistakeholder alliances. Am. J. Manag. Care 2012, 18, S156–S162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kihl, L.A.; Tainsky, S.; Babiak, K.; Bang, H. Evaluation of a cross-sector community initiative partnership: Delivering a local sport program. Eval. Program Plan. 2014, 44, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, A.; MacDonald, A. Outcomes to partners in multistakeholder cross-sector partnerships a resource-based view. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 298–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rok, A.; Kuhn, S. Local Sustainability 2012: Taking Stock and Moving Forward; International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives—Local Governments for Sustainability: Bonn, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, A.; Crane, A. Cross-Sector Partnerships for Systemic Change: Systematized Literature Review and Agenda for Further Research. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, C.; Phillips, N.; Lawrence, T.B. Resources, knowledge and influence: The organizational effects of interorganizational collaboration. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, B.; Lin, Z. Understanding collaboration outcomes from an extended resource-based view perspective: The roles of organizational characteristics, partner attributes, and network structures. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 697–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Erickson, T.A.; Aguilar-González, B.; Loeser, M.R.R.; Sisk, T.D. A framework to evaluate ecological and social outcomes of collaborative management: Lessons from implementation with a Northern Arizona collaborative group. Environ. Manag. 2009, 45, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vurro, C.; Dacin, M.T.; Perrini, F. Institutional antecedents of partnering for social change: How institutional logics shape cross-sector social partnerships. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 94, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, I.; Patton, D.; Lindley, I. Local authorities, business and LA21: A study of East Midlands sustainable development partnerships. Local Gov. Stud. 2003, 29, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, K.; Thibault, L. Challenges in multiple cross-sector partnerships. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2009, 38, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, E.T. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acedo, F.J.; Barroso, C.; Galan, J.L. The resource-based theory: Dissemination and main trends. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Looking inside for competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1995, 9, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 969–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.; Pisano, G. The dynamic capabilities of firms: An introduction. Ind. Corp. Chang. 1994, 3, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Res. Policy 1986, 15, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.K.; Teng, B.-S. A resource-based theory of strategic alliances. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 31–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worley, C.G.; Mirvis, P.H. Studying networks and partnerships for sustainability: Lessons learned. In Building Networks and Partnerships; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; Volume 3, pp. 261–291. [Google Scholar]

- Den Hond, F.; de Bakker, F.G.; Doh, J. What prompts companies to collaboration with NGOs? Recent evidence from the Netherlands. Bus. Soc. 2015, 54, 187–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Bromiley, P. Critical factors affecting the planning and implementation of major projects. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koontz, T.M.; Thomas, C.W. Measuring the performance of public-private partnerships: A systematic method for distinguishing outputs from outcomes. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2012, 35, 769–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The big idea: Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, R.; Moles, R. The development of Local Agenda 21 in the Mid-West Region of Ireland: A case study in interactive research and indicator development. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2002, 45, 889–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Stone, M.M. The design and implementation of cross-sector collaborations: Propositions from the literature. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörby, S.A. Local Agenda 21 in Four Swedish municipalities: A tool towards sustainability? J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2002, 45, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaziji, M. Turning gadflies into allies. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Ko, W.-W. An analysis of cause-related marketing implementation strategies through social alliance: Partnership conditions and strategic objectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J.; Ye, C. How social partnerships build brands. In Social Partnerships and Responsible Business; Seitanidi, M.M., Crane, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, M.K.; Meinhard, A.G. A contingency view of the responses of voluntary social service organizations in Ontario to government cutbacks. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2002, 19, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B. Creating sustainable value. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2003, 17, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westley, F.; Vredenburg, H. Strategic bridging: The collaboration between environmentalists and business in the marketing of green products. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1991, 27, 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.; MacDonald, A.; Ordonez-Ponce, E. Implementing community sustainability strategies through cross-sector partnerships: Value creation for and by businesses. In Business Strategies for Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 402–416. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, T.; Holtbrügge, D. Benefits of cross-sector partnerships in markets at the base of the pyramid. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, M.; Kale, P.; Corsten, D. What really is alliance management capability and how does it impact alliance outcomes and success? Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 1395–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, P.; Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H. Alliance capability, stock market response, and long-term alliance success: The role of the alliance function. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 747–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitanidi, M.M.; Crane, A. Implementing CSR through partnerships: Understanding the selection, design and institutionalisation of nonprofit-business partnerships. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitanidi, M.M. The Politics of Partnerships: A Critical Examination of Nonprofit-Business Partnerships; Springer: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cropper, S. Collaborative working and the issue of sustainability. In Creating Collaborative Advantage; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1996; pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Koontz, T.M.; Thomas, C.W. What do we know and need to know about the environmental outcomes of collaborative management? Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Melo, A.; Mansouri, S.A. Stakeholder engagement: Defining strategic advantage for sustainable construction. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, P.; Robinson, R.B., Jr. New venture strategies: An empirical identification of eight ‘archetypes’ of competitive strategies for entry. Strateg. Manag. J. 1990, 11, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriauciunas, A.; Parmigiani, A.; Rivera-Santos, M. Leaving our comfort zone: Integrating established practices with unique adaptations to conduct survey-based strategy research in nontraditional contexts. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 994–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karros, D.J. Statistical methodology: II. Reliability and validity assessment in study design, Part B. Acad. Emerg. Med. 1997, 4, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. Handbook of Psychological Testing, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Waddock, S.A. Understanding social partnerships: An evolutionary model of partnership organizations. Adm. Soc. 1989, 21, 78–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A. Building successful social partnerships. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1988, 29, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Le Ber, M.J.; Branzei, O. Towards a critical theory of value creation in cross-sector partnerships. Organization 2010, 17, 599–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Neter, J.; Wasserman, W.; Kutner, M.H. Applied Linear Regression Models; Irwin: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie, E.R. The Practice of Social Research, 10th ed.; Wadsworth Publishing Company: Belmont, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Provan, K.G.; Kenis, P. Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2007, 18, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provan, K.G.; Milward, H.B. Do networks really work? A framework for evaluating public-sector organizational networks. Public Adm. Rev. 2001, 61, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.E.; Seitanidi, M.M. Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses: Part 1. Value creation spectrum and collaboration stages. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 726–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.E.; Seitanidi, M.M. Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses: Part 2. Partnership processes and outcomes. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 929–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzei, O.; Le Ber, M.J. Theory-method interfaces in cross-sector partnership research. In Social Partnerships and Responsible Business; Seitanidi, M.M., Crane, A., Eds.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2014; pp. 229–266. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, M.; Arenas, D.; Batista, J.M. Value creation in cross-sector collaborations: The roles of experience and alignment. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, J. Collective action and the group size paradox. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2001, 95, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Lin, H.; Clarke, A. Cross-Sector Social Partnerships for Social Change: The Roles of Non-Governmental Organizations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, S.; Wohlgezogen, F.; Zajac, E.J. Strategic alliance structures: An organization design perspective. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 582–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes, M. Inter-organizational relationships in local and regional development partnerships. In The Oxford Handbook of Inter-Organizational Relations; Cropper, S., Ebers, M., Huxham, C., Ring, P.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 203–230. [Google Scholar]

- Huxham, C.; Vangen, S.E. Managing to Collaborate: The Theory and Practice of Collaborative Advantage; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Googins, B.K.; Rochlin, S.A. Creating the partnership society: Understanding the rhetoric and reality of cross-sectoral partnerships. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2000, 105, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smardon, R.C. A comparison of Local Agenda 21 implementation in North American, European and Indian cities. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2008, 19, 118–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthill, M. The contribution of human and social capital to building community well-being: A research agenda relating to citizen participation in local governance in Australia. Urban Policy Res. 2003, 21, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Marketing | 3.50 | 1.13 | 1 | |||||

| 2. Stewardship | 2.96 | 1.21 | 0.427 ** | 1 | ||||

| 3. Structure | 2.80 | 1.37 | 0.491 ** | 0.469 ** | 1 | |||

| 4. Financial | 2.80 | 1.13 | 0.630 ** | 0.651 ** | 0.520 ** | 1 | ||

| 5. Human | 3.84 | 0.86 | 0.653 ** | 0.404 ** | 0.630 ** | 0.500 ** | 1 | |

| 6. Organizational | 3.85 | 0.92 | 0.595 ** | 0.560 ** | 0.542 ** | 0.629 ** | 0.725 ** | 1 |

| 7. Shared | 3.80 | 0.88 | 0.407 ** | 0.394 * | 0.582 ** | 0.453 ** | 0.619 ** | 0.665 ** |

| Private | Public | Civil Society | Partner for under 7 Years | Partner for 7+ Years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Marketing | 3.17 | 1.21 | 3.83 | 0.69 | 3.44 | 1.28 | 3.43 | 1.24 | 3.60 | 0.66 |

| Stewardship | 3.16 | 1.03 | 2.96 | 1.16 | 2.83 | 1.40 | 3.00 | 1.16 | 2.85 | 1.43 |

| Structure | 2.86 | 1.39 | 3.26 | 1.25 | 2.38 | 1.38 | 2.70 | 1.40 | 3.00 | 1.31 |

| Financial | 2.81 | 0.83 | 3.21 | 1.24 | 2.44 | 1.17 | 2.74 | 1.18 | 2.82 | 1.01 |

| Human | 3.72 | 0.81 | 4.10 | 0.47 | 3.76 | 1.07 | 3.73 | 0.92 | 4.20 | 0.47 |

| Organizational | 3.88 | 0.68 | 4.13 | 0.64 | 3.67 | 1.18 | 3.72 | 0.10 | 4.30 | 0.39 |

| Shared | 3.97 | 0.98 | 3.94 | 0.79 | 3.57 | 1.12 | 3.55 | 0.97 | 4.57 | 0.19 |

| B | SE B | β † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −0.20 | 0.43 | |

| Marketing | 0.38 ** | 0.13 | 0.38 |

| Stewardship | 0.41 *** | 0.12 | 0.45 |

| Structure | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.62 |

| Duration | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.03 |

| Private sector | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.31 |

| Public sector | 0.52 | 0.29 | 0.08 |

| Adjusted R2 = 0.56; ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 | |||

| † Standardized coefficient | |||

| B | SE B | β † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.90 | 0.34 | |

| Marketing | 0.32 ** | 0.10 | 0.41 |

| Stewardship | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Structure | 0.24 ** | 0.09 | 0.38 |

| Duration | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.19 |

| Private sector | −0.13 | 0.23 | −0.07 |

| Public sector | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.01 |

| Adjusted R2 = 0.52; ** p < 0.01 | |||

| † Standardized coefficient | |||

| B | SE B | β † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.61 | 0.37 | |

| Marketing | 0.27 * | 0.11 | 0.33 |

| Stewardship | 0.27 ** | 0.10 | 0.36 |

| Structure | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

| Duration | 0.56 * | 0.24 | 0.26 |

| Private sector | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.04 |

| Public sector | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.13 |

| Adjusted R2 = 0.50; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 | |||

| † Standardized coefficient | |||

| B | SE B | β † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.17 | 0.38 | |

| Marketing | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Stewardship | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.19 |

| Structure | 0.24 * | 0.10 | 0.38 |

| Duration | 0.80 ** | 0.25 | 0.39 |

| Private sector | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.04 |

| Public sector | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.13 |

| Adjusted R2 = 0.44; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 | |||

| † Standardized coefficient | |||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

MacDonald, A.; Clarke, A.; Huang, L.; Seitanidi, M.M. Partner Strategic Capabilities for Capturing Value from Sustainability-Focused Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships. Sustainability 2019, 11, 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030557

MacDonald A, Clarke A, Huang L, Seitanidi MM. Partner Strategic Capabilities for Capturing Value from Sustainability-Focused Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships. Sustainability. 2019; 11(3):557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030557

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacDonald, Adriane, Amelia Clarke, Lei Huang, and M. May Seitanidi. 2019. "Partner Strategic Capabilities for Capturing Value from Sustainability-Focused Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships" Sustainability 11, no. 3: 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030557

APA StyleMacDonald, A., Clarke, A., Huang, L., & Seitanidi, M. M. (2019). Partner Strategic Capabilities for Capturing Value from Sustainability-Focused Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships. Sustainability, 11(3), 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030557