1. Introduction

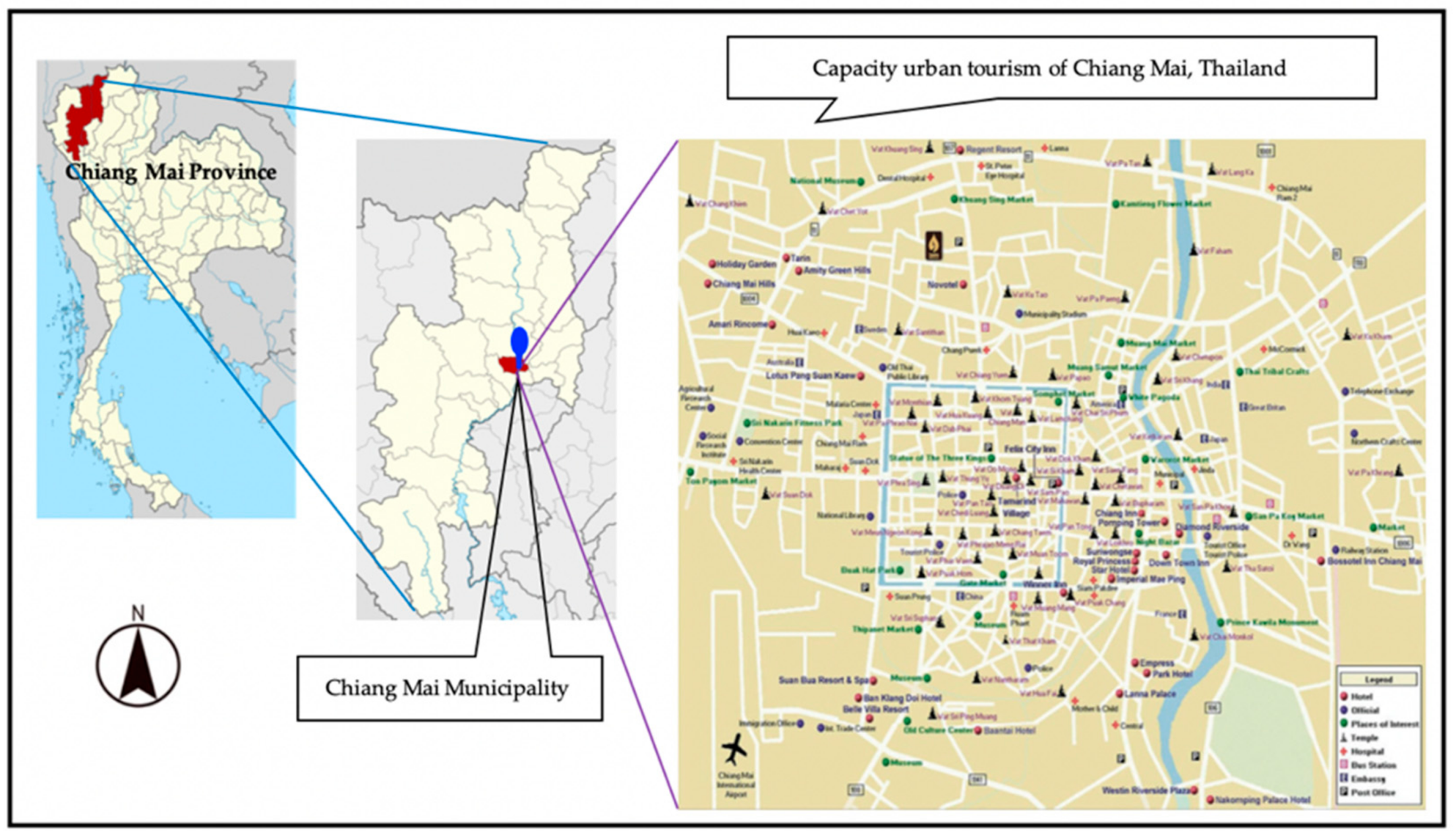

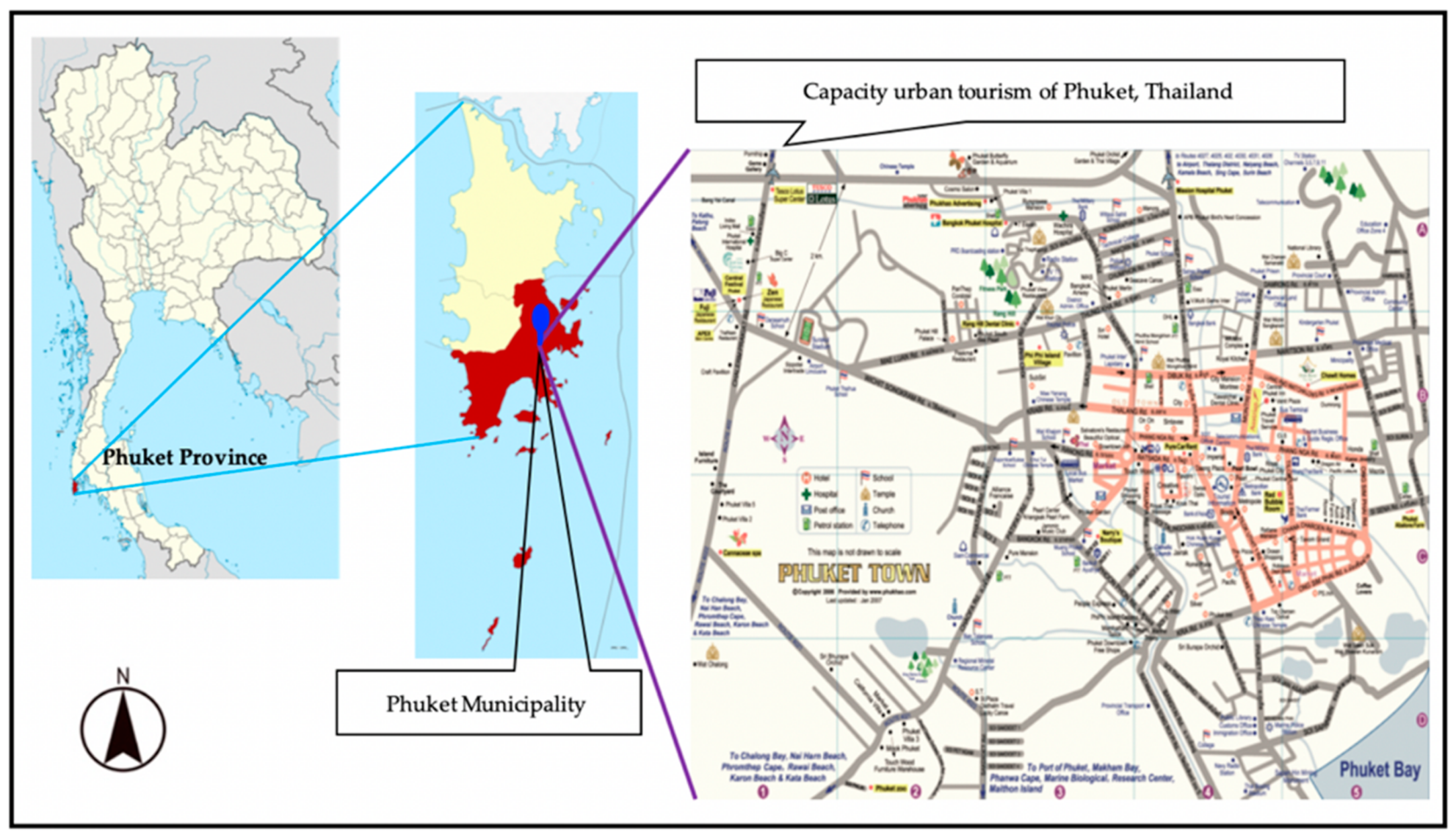

In this article, a focus on a fundamental framework for urban tourism development plan formulation in Thailand, towards sustainability in the local governments of Chiang Mai Municipality and Phuket Municipality—as tourism cities whose urban tourism growth rate was the highest of the cities in Thailand, second only to Bangkok—was emphasized. In recent decades, tourism has been the most rapidly growing industry in the world [

1], an important tool which has made money for cities and other sectors, and the cluster which has been most important to the city’s economy [

2,

3]. Urban tourism has become one of the tourism sectors that has had the most rapid growth in the world [

4] and replaced the traditional industry [

5]. The city requires good management or new urban development to cause urban tourism, which will provide opportunity and cause the city to be more compact. However, urban tourism regeneration involves strategic planning to instigate change through new developments [

2,

6,

7,

8,

9]. When change and regeneration are addressed, they will form an important concept concerning spatial transitions [

10,

11]. While physical regeneration projects may be deemed necessary to support economic development, competitiveness and growth of tourism [

10,

12,

13], it is also important to focus on its intangible results, impacts, legacies and social benefits [

14].

Urban tourism is a complex phenomenon consisting of various activities and depending on many factors [

2,

15,

16]. There are many aspects which closely connect to urban development. However, the impacts of environment and quality of life have been paid attention slightly. Most of the research has focused on economic factors, because tourism has become a motivator of the local economy [

17,

18]. Implementation has been in line with marketing strategies to respond to the tourists’ needs and expectations, which have been the essence of urban tourism development planning [

19]. The city’s residents have not been a significant part of this planning. The urban dynamics and the growth of urban tourism can lead to the immense consumption of all kinds of resources. Urban renewal can also lead to urban sprawl. These processes are the dynamics of tourism industry and cause urban renewal, which will lead to the flow of capital, labour, goods and services. The cities’ importance will be increased in terms of finance, services, entertainment, and facilities. Not just foreign investors, but also tourists, will be attracted to the cities [

20,

21]. If the cities are developed and managed in the appropriate direction, they will be effective cities and cities of opportunities, which have more interactions between the residents and tourists [

22].

Although there have been attempts in academia and in the literature to explain the link between urban tourism, urban renewal/conservation [

23,

24,

25], and sustainable urban tourism development, and develop an indicator for a sustainability assessment of urban tourism [

26], a different sustainability study and analysis of urban tourism will result in a solution gap. The main issue, which indicates the necessity of formulating a holistic conceptual framework of the local governments, communities and residents who can promote sustainability is the participation of the urban residents and stakeholders, which has always been neglected and restricted to protect and design urban development and tourism [

6,

19]. Despite this, they should have roles in [

17] continuous and actual planning. However, the participation process of urban tourism planning is still restricted regarding development.

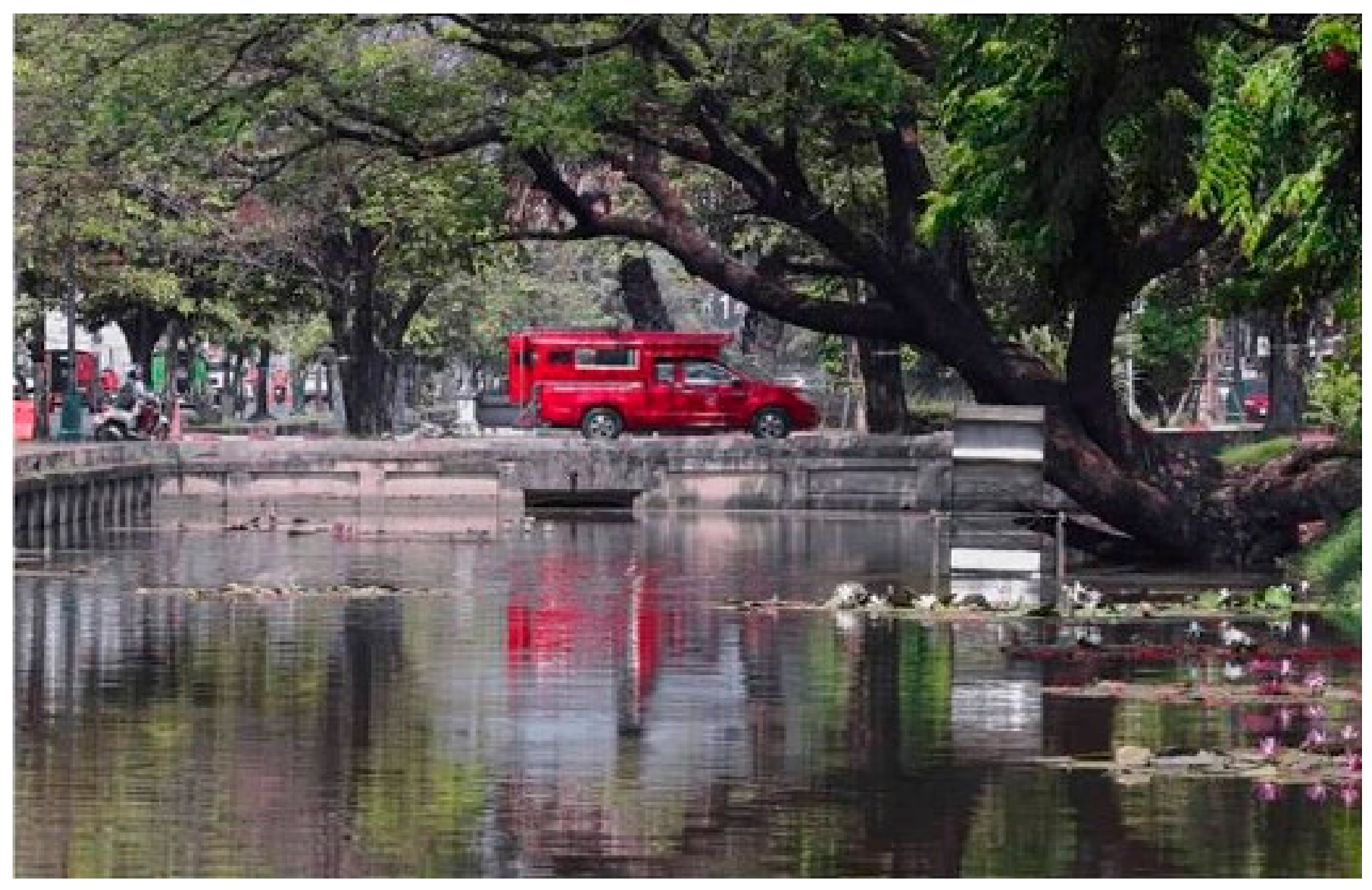

Moreover, a challenge for Chiang Mai and Phuket is the need to stimulate the urban economy by attracting investment from both domestic and foreign investors. "Tourism" is a tool to help the city increase the number of visitors by using its urban foundation and heritage, such as urban history, urban landscape, urban culture, urban identity and tradition, as well as regular and specific tourism activities to attract tourists. However, urban development planning still lacks clear and concrete links between groups of urban stakeholders, because policy is designed and formulated by the central government for implementation by local governments. The gap between central governments, local governments, communities, and academic sectors is also a gap between cities. In order to achieve balance in all dimensions and urban well-being in society, and increase the ability to support tourism and reduce the impact of tourism, the city must be efficiently planned in terms of infrastructure, the construction of buildings, and preservation of urban cultural heritage and history. The way of life of urban citizens and environmental problems must be important issues, which both cities must emphasize. Both cities should also have the urban common goal in urban development and urban tourism of balance in every dimension: society, economy, culture, urban citizens, and tourists.

Hence, in brief, this article aims to focus on analyzing/synthesizing the holistic conceptual framework foundation of urban tourism development plan-making practices towards sustainability, in order to explain how an urban tourism development action plan was made in accordance with the sustainable tourism development policy in Thailand, and the overall participation in the urban tourism development plan-making practice.

The following sections will present the first part of the literature review, “Sustainable development background in Thailand”, which emphasizes the importance of Thailand’s policy development and development plan towards Sustainable Development Goals. The second part mentioned the integration of urban tourism planning towards sustainability. The third explained the important types/activities of a case study area and the research design. The fourth showed the results of the study. After that, the author suggests the possible driving framework of a sustainable urban tourism development plan to promote the stakeholder participation which currently exists, for further research development in the future.

2. Sustainable Development Background in Thailand

“Sustainable development” is not a new issue for the development goals of the world community, but it is a goal that has challenges, aiming to create a balance of social, economic and environmental dimensions, as well as balance among government sectors, private sectors, and community sectors [

26]. Sustainable development was mentioned for the first time in the 1980s, because there was a growing awareness of environmental crises and problems regarding the extravagant usage of resources for continuous development of economic growth policy, and inequality of benefit and capital distribution [

17]. The traditional concept of sustainable development consists of two key dimensions [

27]: ecological and socially equitable sustainable development [

28] and problems related to society, morals, ethics, and the environment [

29]. Local empowerment [

30] was included in the concept of sustainable development. Nowadays, sustainable development is regarded as the process which attempts to improve the living conditions of citizens, including quality of life, such as access to education, fundamental rights and freedom, public services, and general welfare [

31]. The definition of sustainable development was expanded to cover the conduct of development around the world and human resource development by the principal of self-help, which also covers development economics, society, culture, the environment, and ethics [

32].

In September 2016, the United Nations (UN) voted to adopt sustainable development goals (SDGs) in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) as the global development agenda in the next 15 years or, over the period 2017–2023 [

33], under the concept of “ Use of natural resource and environment use for sustainable development to continue the mission which is not achieved yet under Millennium Development Goals and expand the development framework to cover all countries which are both developing and developed countries.” Therefore, development of the world in the new era should have a sustainable balance in economic, social and environmental aspects.

In Thailand, the concept of sustainable development was introduced in 1973. Thailand’s development in the past was influenced by the economic concept of neo-liberalism and the economic policy set, which was called the “Washington Consensus.” It can be indicated that the first to the seventh National Economic and Social Development Plan of Thailand, from 1961 to 1996, focused on economic growth building rather than human resource development, social welfare systems, and equilibration of the ecosystem. Although Thailand’s economy had rapid growth, as the growth rate of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was 7%–8% per year in the era before the economic crisis in 1997, the economic crisis indicates that GDP, although high, did not bring stable happiness to the people in the country [

33]. In addition, it also reflected the weak spots and several obstacles in the country’s development, such as overproduction and overconsumption, overdependency on export and foreign markets, lack of good governance of senior administrators in both public and private sectors, and insufficient welfare management of the government sectors.

Because of the lessons learned during the economic crisis and the influence of the sustainable development concept, Thailand adjusted development to be more balanced and sustainable. The Sufficiency Economy Philosophy (SEP) of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej was introduced to support the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals. Nowadays, the Royal Thai Government specified to carry out reform plans in any areas which are specified in the constitution of The Kingdom of Thailand, B.E. 2560 (2017) [

33], as well as other intermediate-range plans and long-range plans such as The Twelfth National Economic and Social Development Plan (2017–2021) [

34], National Digital Economy and Society Development Plan, and the 20-year National Strategy (2018–2037), in line with the Sufficiency Economy Philosophy and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations, in order to drive the country to be balanced and sustainable in the context of changes which will be faced in the future.

Sustainable development has become an important part of the formulation of policy in the Top-down approach. However, it is also an aspect of development policy in the level of Macro-policy making, which is a wide level and develops practices by considering the local imbalance regarding sustainable integration. Hence, the integration of tourism policy must formulate policy at the level of Bottom-up approach, by shifting the level of micro-policy making towards sustainability, to maintain a balance of resources which will promote the economic, social, environmental, and cultural development of the community. Tourism in the city is one of the economic activities which must compete with other industries for the same resources. However, this negatively affects resident’s perception of tourism. Local governments need to plan and formulate more sophisticated policies, requiring cooperation from both the public and private sectors. Therefore, it is necessary to understand urban tourism development based on maintaining the balance of urban resources.

3. Urban Tourism Integration towards Sustainable Development

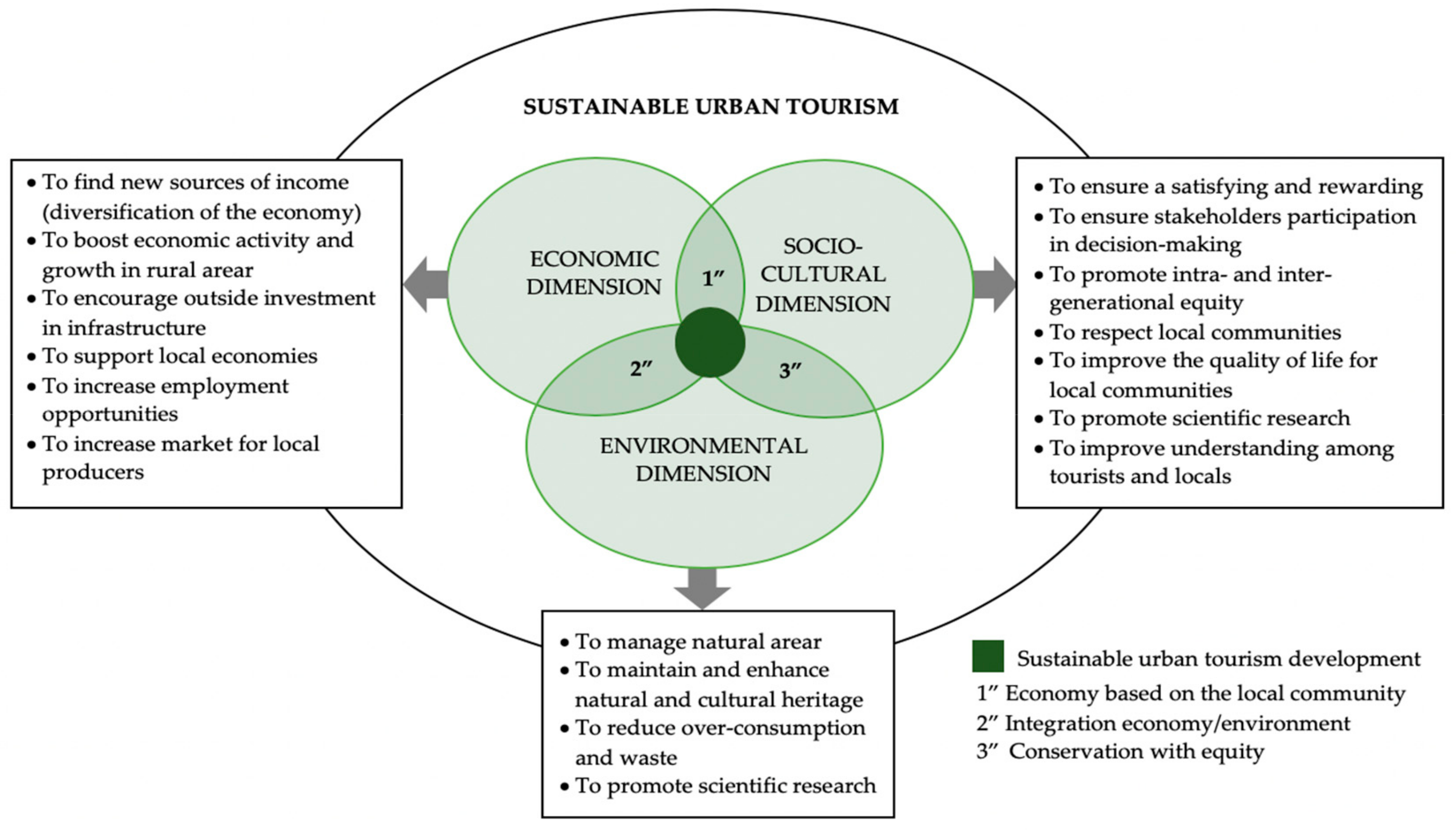

Sustainable tourism poses challenges in three dimensions: environmental, social and economic sustainability [

35]. Tourism is involved in environmental, social and economic sustainable development [

36]. Many approaches, however, tend to focus on only one aspect of a system’s overall sustainability, either environment or economic sustainability [

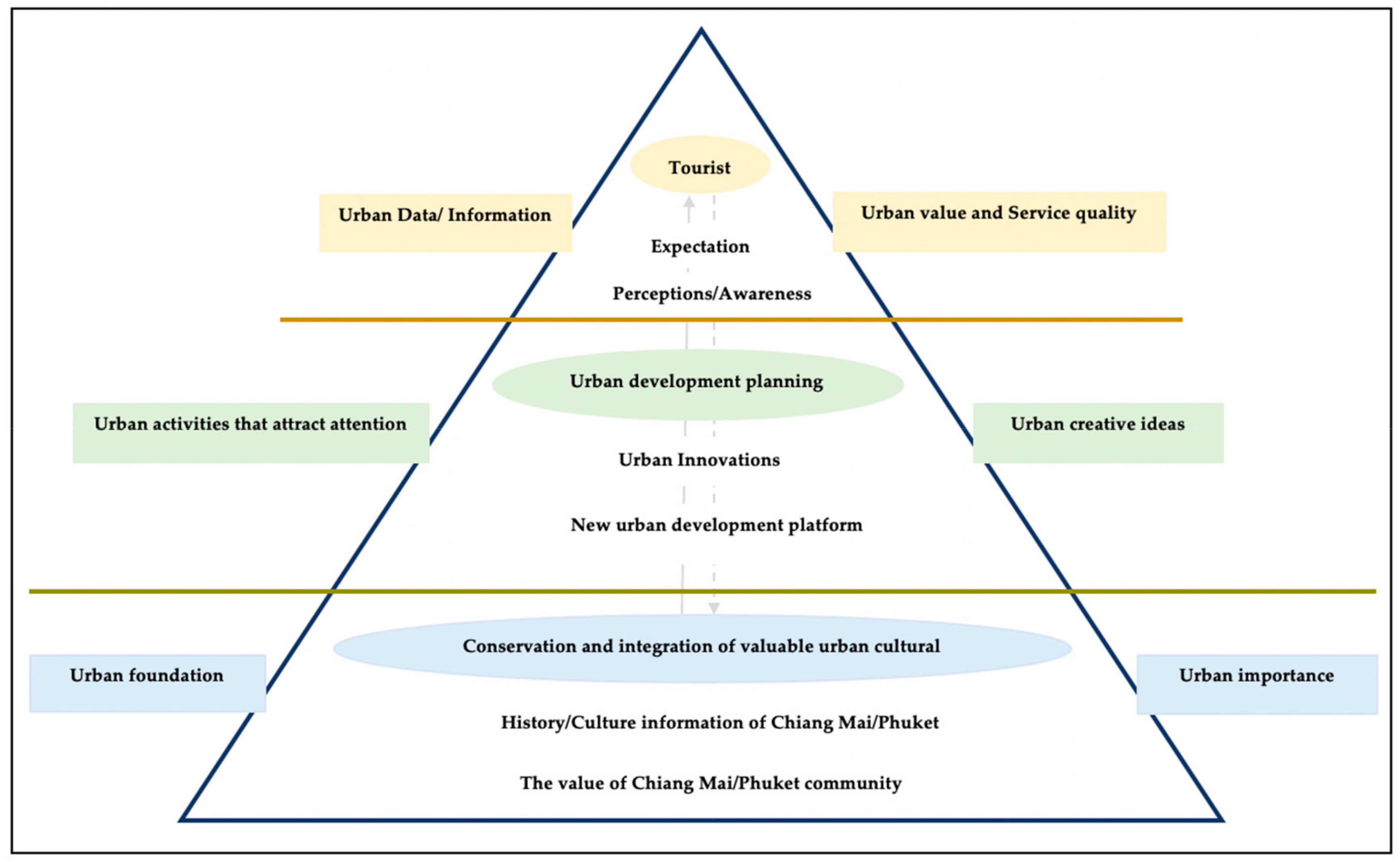

37]. The sustainable tourism development plan consists of three dimensions—1) economically, by increasing service and resource recovery; 2) environmentally, by recycling, avoiding environmental degradation, and the reduction of land removed from agricultural use; and 3) social, by increasing employment, helping the traditional population to attract tourism—as measures of physical and political regeneration (

Figure 1). In the same way, sustainable development in the tourism industry was found to be difficult to specify [

38]. Sustainable tourism occurs in contrast to mass tourism, which negatively affects all dimensions [

39]. It has received wide attention and is accepted by international organizations and the governments of various countries. The concept is then applied in legal forms [

40], including in Thailand.

The basic principles of sustainable tourism development policy are the natural resources, societies, and cultural resources which should be protected [

42]. Tourism policy in Thailand is involved in economic, social, cultural and environmental development through various tourism activities. The dimension of economic development focuses on making money, stimulating the local economy, and creating local jobs. The dimension of social development focuses on restoring lifestyles, creating a social exchange and learning through tourism activities in the community. The dimension of cultural development focuses on restoring culture and traditions as a tourism resource, such as "cultural tourism", and the dimension of environmental development focuses on good environmental conservation as a tourism resource and creates a motivation for environmental conservation, such as "ecotourism".

“Urban tourism development” is necessary for natural, environmental, and cultural heritage protection, conservation of social and culture values, the development of the quality of life of the residents who live in the urban area, and economic development [

43]. However, when looking at the benefits of urban tourism, regarding the use of resources in all three dimensions of sustainability, achievement of these goals is not at the same level. The main target is the economy [

18], although environmental impact and climate change were paid some attention [

44]. Urban tourism development has a multidimensional link, and urban residents, policymakers, and stakeholders must be aware of the complexities of urban tourism and its multifunctional character [

26].

The acceleration of urban tourism’s growth, especially cultural attractions, monuments and museums, has led it to become a very crowded place. [

2] This perspective has a tremendous impact on cultural urban tourism, as culture tourism products are no longer created and marketed for tourists only, but are also thought within a broader context that includes raising the quality of life in the city. [

45] Lack of awareness of comprehensive planning will cause culture, residents and tourists to face problems resulting from the negative impact of careless tourism promotion, because the "urban tourism industry " is unable to clearly identify and restrict itself. [

2] Which the cultural regeneration undertakings and the development of urban creative industries, all aim to address the culture and leisure consumption needs of the local people while providing a competitive advantage to the city for tourism purposes as well [

45]. So, urban tourism whether analysed from the side of uses or users, was so embedded in the city as a whole that the "urban tourist" could only be conceived alongside and overlapping with other "cities" [

2].

Thus, urban tourism planning and management requires a balance of tourism development, and the preservation of culture, environment, and society, as well as transportation, to support urban sustainability in achieving the challenges of all of the dynamic change processes of the city: the protection of natural resources, culture, architecture, environmental management and the city’s physical management, to waste collection and wastewater treatment [

26,

46]. For the tourists, the urban tourism experience appears to be a zero-priced, freely accessible public good. The markets, monuments, museums and general atmosphere of the city are either free public spaces or provided well below cost as a public service [

2].

Even though urban tourism is a form of attraction for the development of urban tourist attractions and residences, the physical rehabilitation of the city through the work carried out on the area, residents and stakeholders [

6], the tourist as a tourist can be seen as a parasitical free-rider on facilities someone else is paying for, although, of course, the tourist is a citizen and taxpayer, and may well be contributing here or elsewhere. This shows that sustainable urban tourism development depends on the views and needs of residents and key stakeholder groups, through the creation of norms and values for the joint development of the stakeholder network, to acknowledge the changes in sustainable urban tourism management approaches towards the formulation of policy and development plans, to decide to use the common strategy and policy [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51].

Furthermore, “Good Governance” is an important principle and practice because it covers the decision scope in the formulation process of policies and plans for urban tourism development towards sustainability [

50]. It is impossible to deny that the direction of tourism policy-making is most likely to seize opportunities to formulate strategies to earn money and increase employment. According to this view, local and central governments play an important role in formulating policies and regulating urban tourism, which changes in a dynamic form and is one of the causes of urban context changes [

52]. In other words, the need for urban tourism development towards sustainability is a long-term perspective, which tries to find solutions and prevent problems caused by tourism and urban growth, especially climate change. The future impact depends on the plans and policies regarding current sustainable urban tourism development, with new technologies and innovations which will increase the participation of urban residents who currently cannot share and access information and need to be more involved in the formulation of solutions [

53].

Moreover, Høyers (2000) [

54] presented a solution and sustainable urban tourism development, as well as forms of congestion reduction and forms of local mobility or public transportation [

55], and gave priority to the dissatisfaction of urban residents towards urban tourism. In addition, Becken and Patterson [

56] indicated that plans or statistical collection methods of emissions from tourism activities should be formulated in a correct and comprehensive way, because most tourism activities use energy in both direct and indirect ways. Notwithstanding, some critics think that implementation in line with the principles of sustainable development in urban tourism is complex and difficult when we compare it to other industries, due to the different needs and interests of key stakeholders [

57]. The government is also hesitant to change the tourism sectors because it focuses on the growth of the urban tourism industry in the economic dimension rather than in others [

58,

59] and is often dominated by administrative and decision-making powers [

60].

Therefore, urban tourism development that leads to sustainability must occur from the integrated process of supporting resources, exact policy making processes, Human Resource Development, and a common and clear perception of tourists.

5. Results of the Study

5.1. The Capacity of the Area for Urban Tourism Development towards Sustainability

The capacity and readiness of the area at present, and the future expectations of urban tourism development towards sustainability, showed that the current capacities and readiness of urban Chiang Mai were at a high level (average = 3.99) and the expectation of the future capacity and readiness for development of urban Chiang Mai was at the highest level (average = 4.84).

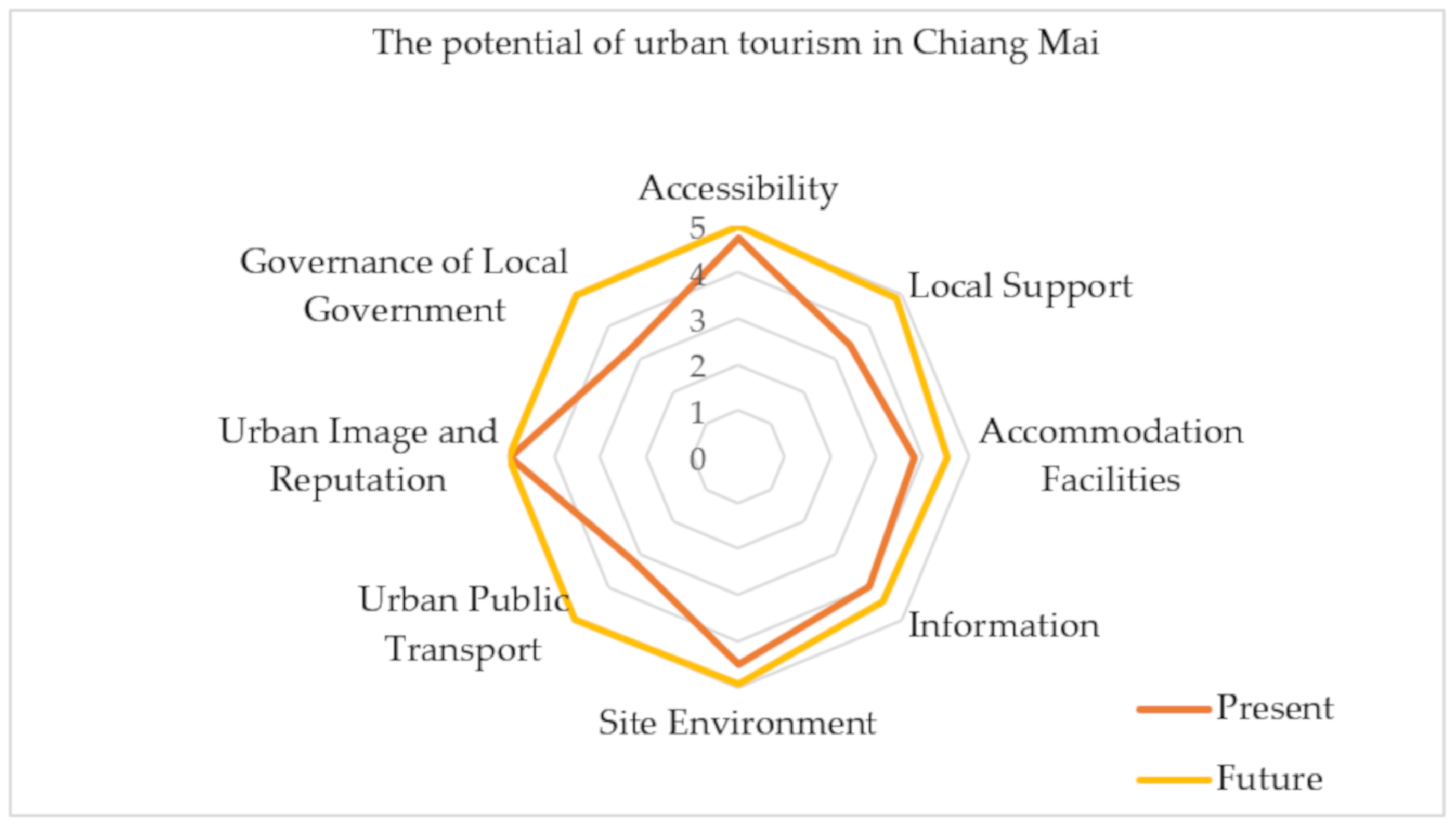

Regarding the current capacity and readiness of urban Chiang Mai (

Figure 12), the most mentioned area by the informants was "urban image and reputation" (average = 4.92, highest), followed by "accessibility" (average = 4.75, highest), "site environment" (average = 4.52, highest). The current capacity and readiness averaged at the level of high; the only current capacity and readiness that had a medium average was "urban public transport" (average = 3.21, medium). The expectation of the future capacity and readiness development of urban Chiang Mai was at the highest level. The future capacity and readiness of urban Chiang Mai with the highest score was "urban image and reputation" (average = 5.00, highest), followed by "accessibility" (average = 5.00, highest) and "urban public transport" (average = 5.00, highest). The other the future capacity and readiness aspects also averaged at the highest level.

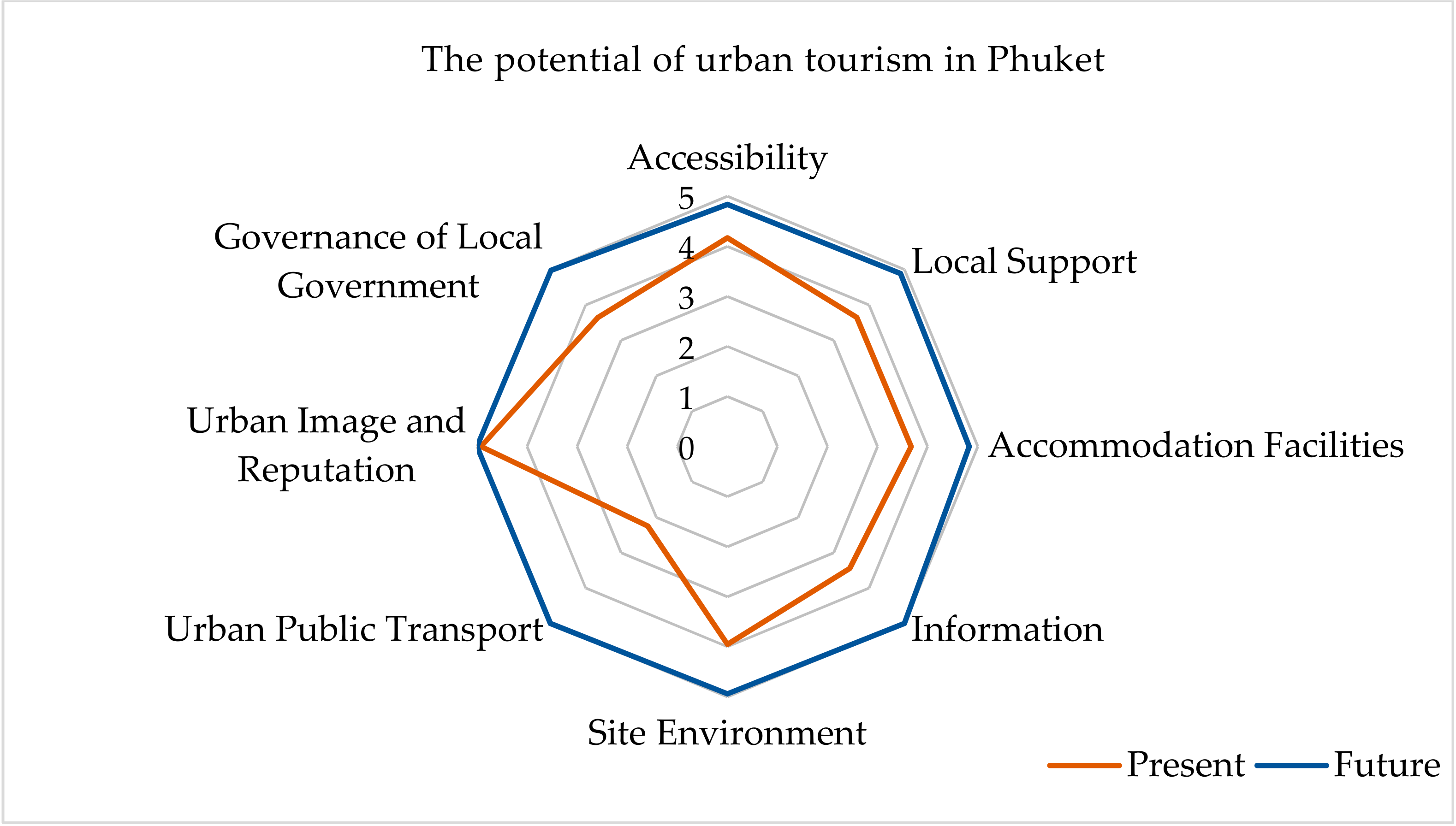

Further, the capacity and readiness of the area at present and the future expectations of urban tourism development towards sustainability found that the current capacity and readiness of urban Phuket were at a high level (average = 3.71), and the expectation of the future capacity and readiness development of urban Phuket was at the highest level (average = 4.93).

Regarding the current capacity and readiness of urban Phuket (

Figure 13) the most common response from the informants was "urban image and reputation" (average = 4.95, highest), followed by "accessibility" (average = 4.71, highest). The other the current capacity and readiness aspects averaged at a high level, and the only current capacity and readiness that had a low average was "urban public transport" (average = 2.21, low). The expectation of the future capacity and readiness development of urban Phuket was at the highest level. The highest score for future capacity and readiness of urban Phuket was "urban image and reputation" (average = 5.00, highest), followed by "urban public transport" (average = 5.00, highest), and "information" (average = 5.00, highest).The other the future capacity and readiness also averaged at the highest level.

5.2. The Five Year Urgent need for Urban Tourism Development towards Sustainability

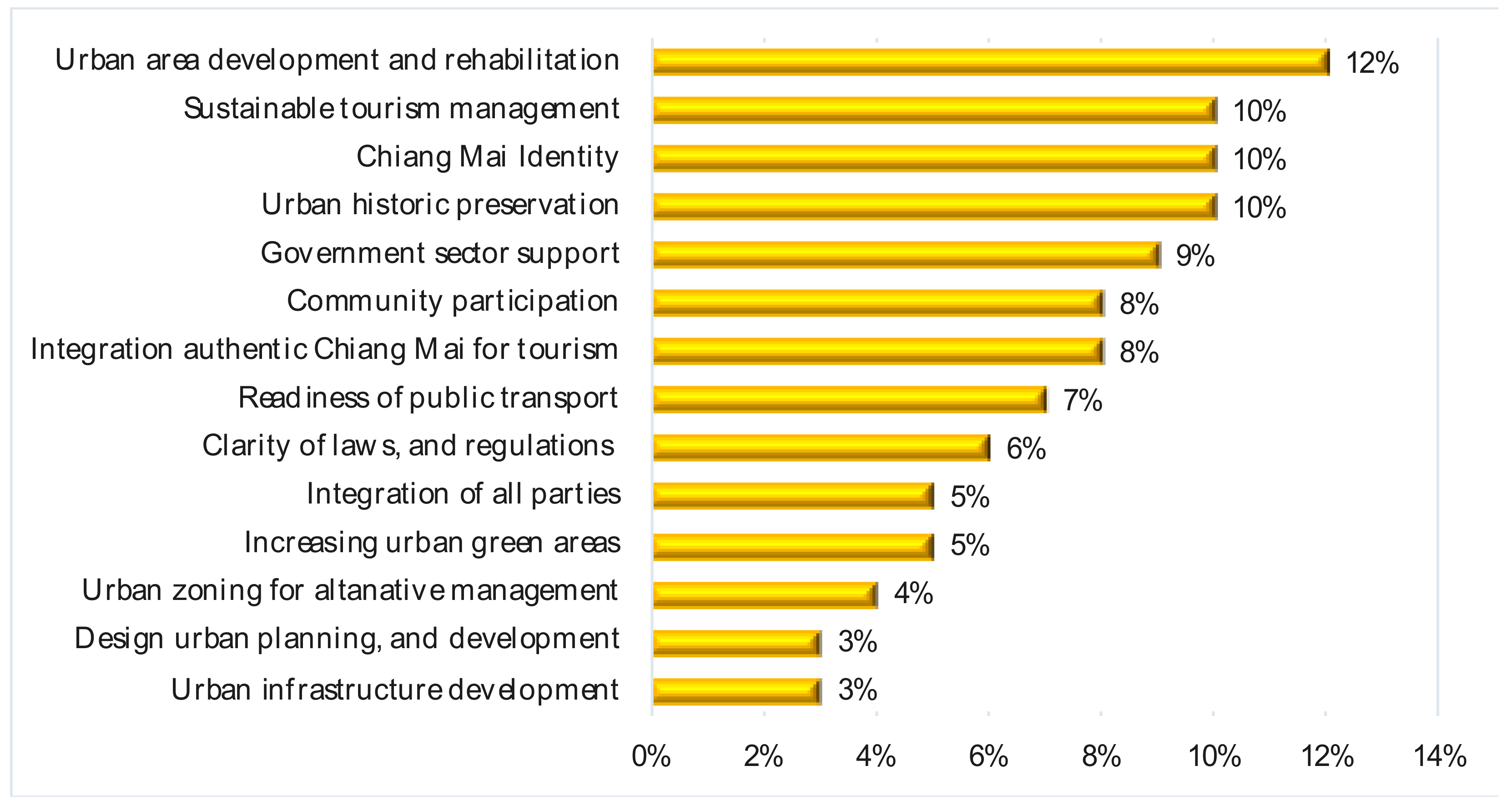

Regarding the Five Year Urgent Need for Urban Tourism Development towards sustainability to the exigency of urban tourism development in Chiang Mai (

Figure 14) the most common response from informants was "urban area development and rehabilitation", mentioned by 12% of informants, followed by "Chiang Mai identity, urban historic preservation, and sustainable tourism management", each accounting for 10% of informants, and "government sector support", with 9% of informants. The "urban zoning for alternative management" was preferred by only 4% of informants.

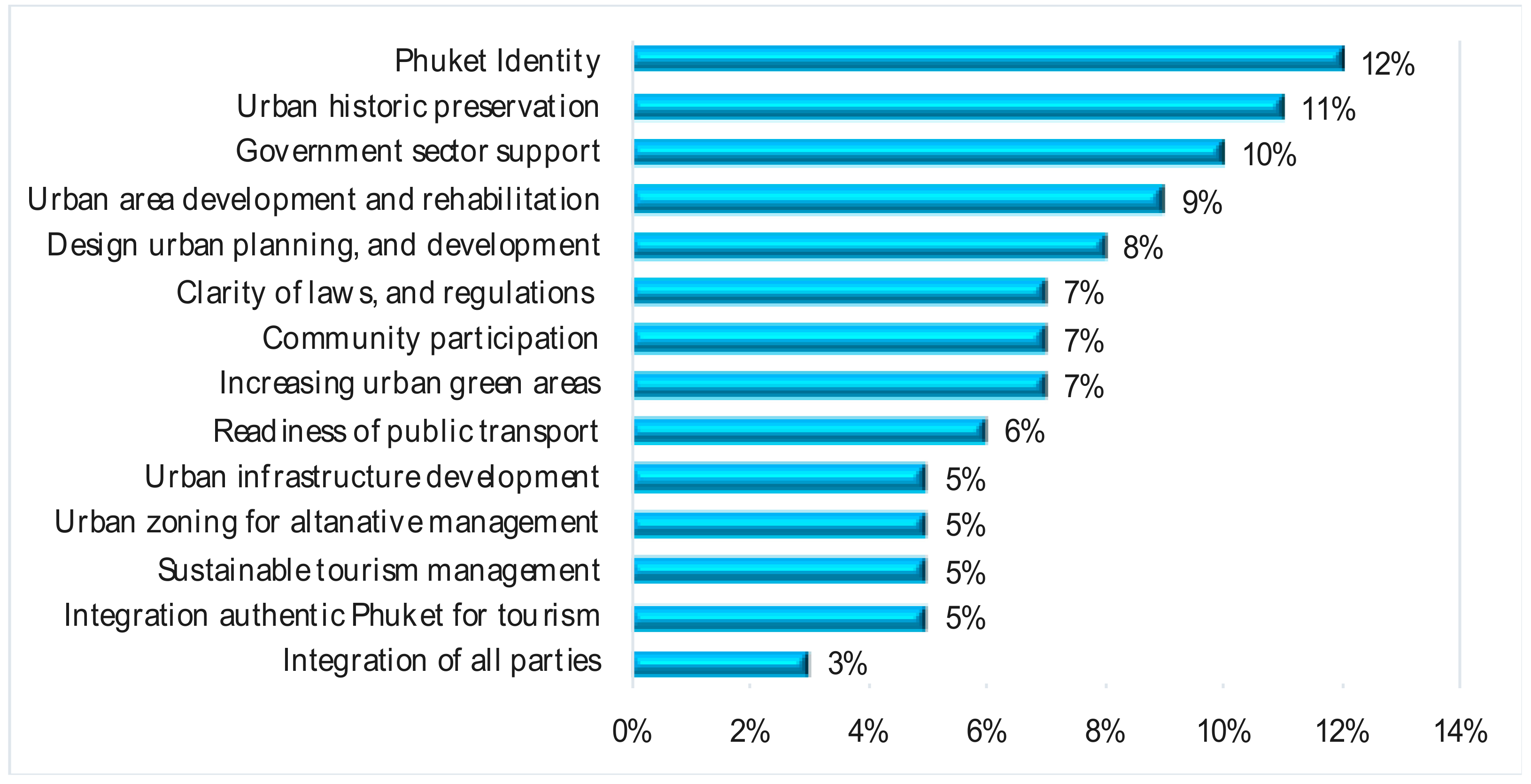

Likewise, regarding the exigency of urban tourism development in Phuket (

Figure 15) the most common response from informants was "Phuket identity", with 12% of all informants, followed by "urban historic preservation", with 11% of informants, and "government sector support", with 10% of informants. The "integration parties" was preferred by only 3% of informants.

5.3. Fundamental Problems of Urban Development and Urban Tourism Development in Thailand

The problems of urban and urban tourism development focused on in the question "What are fundamental problems of urban developing and urban tourism developing in Thailand?"

Urban tourism development in Thailand is a new issue that has attracted the attention of the central government, local government, communities and academics. This article presents the results of an interview showing the integration of tourism development agencies that may not achieve development goals towards sustainability, a living and safe society, and environmentalism, due to a lack of standardized planning, which causes urban development strategies to be directionless. “Lack of common agreement and a common goal, Planning for common development direction specification (3), and “Yes’ the currently it does not have an exchange of data and information between agencies” (5,6).

In addition, government operation is still delayed with regards to changes in global situation, which must be adjusted for all the time. Planning for physical development may not promote and control the direction of urban expansion and the number of tourists— “Most development plans is based on past problems, not from the future development strategies". (3), and "The city lacks innovation or new tools for urban development that are a mechanism to push forward the economy and society to progress and occur creative development.” (6)—or the development of infrastructure, public utility systems, urban traffic and transportation systems.

Moreover, it was found that “Investments which mainly support travel and road transport are urban sprawl promotion that causes the city to grow without direction. Moreover, it lacks support and awareness of the people in the area” (11,13). Social, economic, and environmental sustainability are also strategically important for urban tourism development, which has attracted the attention of policymakers and stakeholders, in the integration of diverse urban development policies in Thailand in order to alleviate problems and prevent the negative impacts of tourism and conflicts about with urban residents. Chiang Mai and Phuket have developed processes and methods of development in area-based management by ordering the various needs of area-based development, to specify area-based strategies regarding the expectations of urban tourism growth.

5.4. The Integration of Sustainability into Urban Tourism Policies

The integration of sustainability issues with tourism plans and area development plans is a new challenge for Thailand and urban tourism, because there are many different aspects to consider. Integration focuses on cross-sectoral integration in three dimensions: the integration of the mission, area-based dimensions, and the cooperation of the government sector, private sector, community, civil society, academic sectors at the provincial level, provincial groups, special areas and other specific capacity areas towards a common goal: “Thailand is stable, prosperous, sustainable, a developed country with development based on the philosophy of the sufficiency economy”. The foundation of sustainable development is society and the economy. Tourism industries and services are both the tools and the mechanism for the management and development of urban areas, in order to drive balance. “Tourism development, especially urban tourism in the city which has direct contact with the community, living and sharing of resources among community members and tourists must be integrated on strategically, area based, mission and budget at both the Ministry level to the local administrative organization”. (3)

Chiang Mai and Phuket evaluated sustainable issues of urban tourism development to see if they were consistent with the community’s, and tourists’, needs. They recognize the need to solve the problems and protect the resources of crowded areas, and areas which have many tourists in determining local provisions and practices in the area. (

Figure 16) “

We formulate development plans by issuing ordinances as a requirement for entrepreneur in the urban areas which are the center of urban tourism, through cooperation with communities in accordance with national strategies, Act and master plans which focuses on the inheritance of artistic, cultural and local wisdom, natural resources and the environments”.(1,2)

The interviewees had a similar view to Chiang Mai and Phuket, believing that integrating urban tourism planning drives sustainability, which is divided into three levels. According to urban tourism activities, the levels of the systematic urban planning were:

First level: Urban foundation/Urban important—reviews of the urban foundation through exploration and surveys, including urban history, urban value, and urban culture and tradition, as well as an urban environmental assessment. The information will lead to the management of the urban area being enshrined in the urban plans, developing urban conservation for the local government, national government and communities;

Second level: Urban creation and innovation—developed using the unique characteristics of the area and the capability to support and promote urban industrial integration, and actively guide social capital through title sponsorship, resource replacement, cooperation and other forms of promotion, to build a large platform for all types of urban tourism-related industry enterprises, associations, and media which increase urban economics in Chiang Mai and Phuket, such as MICE city, Sport city, etc.;

Third level: Tourists—the perception and awareness of tourists through communication of the urban story, from data and information about Chiang Mai and Phuket, such as urban features, urban rules and regulations, etc.

According to

Figure 16, expanding the key findings of the overall conceptual base model of Thailand’s urban tourism development towards sustainability involves several different aspects: firstly, increasing the knowledge of the urban society through urban foundation and wisdom, and sharing the gained pieces of information to inter-organizations; secondly, adding urban values to knowledge and innovation that could lift or enhance quality of life and the standard of living of urban citizens; thirdly, reflecting urban citizen’s (Chiang Mai and Phuket) understanding to innovatively apply their knowledge and information to the planning-making of urban tourism development toward sustainability; finally, to raise the urban communities and their performance using their knowledge.

Furthermore, policies, strategies, plans, and urban tourism development projects in Thailand are divided into three main categories, in line with the way they use sustainable development strategies to develop and maintain a balanced tourism in Chiang Mai and Phuket:

Chiang Mai and Phuket have tourism plans which focus on area-based and mission tourism development, as well as mechanisms and processes to integrate relevant agencies to create unity in sustainable urban tourism management;

Chiang Mai and Phuket have tourism plans that support the development of the capacity to support tourists and tourist attractions at different levels, in order to provide facilities for tourists which are also important measures in conserving and restoring natural resources and the environment, which is important to ensure sustainability;

Chiang Mai and Phuket have tourism plans to connect tourist destinations that are diverse in nature, history, art, culture, way of life, local communities, traditions and local wisdom, as well as products and services that display local identities, by identifying tourism networks that are in line with the tastes and needs of tourists.

The change is evident from the apparent enthusiasm for supervising urban tourism throughout the planning process, and the management of the strategic plan, including cooperation from all sectors involved in the operation, development management in a balanced form of economy, society and environment, by prioritizing public participation, development guidelines from bottom to top (Bottom Up), decentralization, and transparent practice (Transparency). Brainstorming people’s opinions, in accordance with democratic principles, is a framework which can create benefits for people in the area and local communities. This will increase employment, income, and quality of life, which will lead to the standardized quality of the community, strengthen the well-being of local communities, distribute income fairly, develop economic foundations and reduce inequality. At the same time, the production of goods and services must consider the maintenance of natural and cultural resources, in order to deliver as much natural and cultural heritage to the next generation as possible.

5.5. Urban Tourism Development Framework towards Sustainability

5.5.1. Chiang Mai Tourism Development Framework towards Sustainability

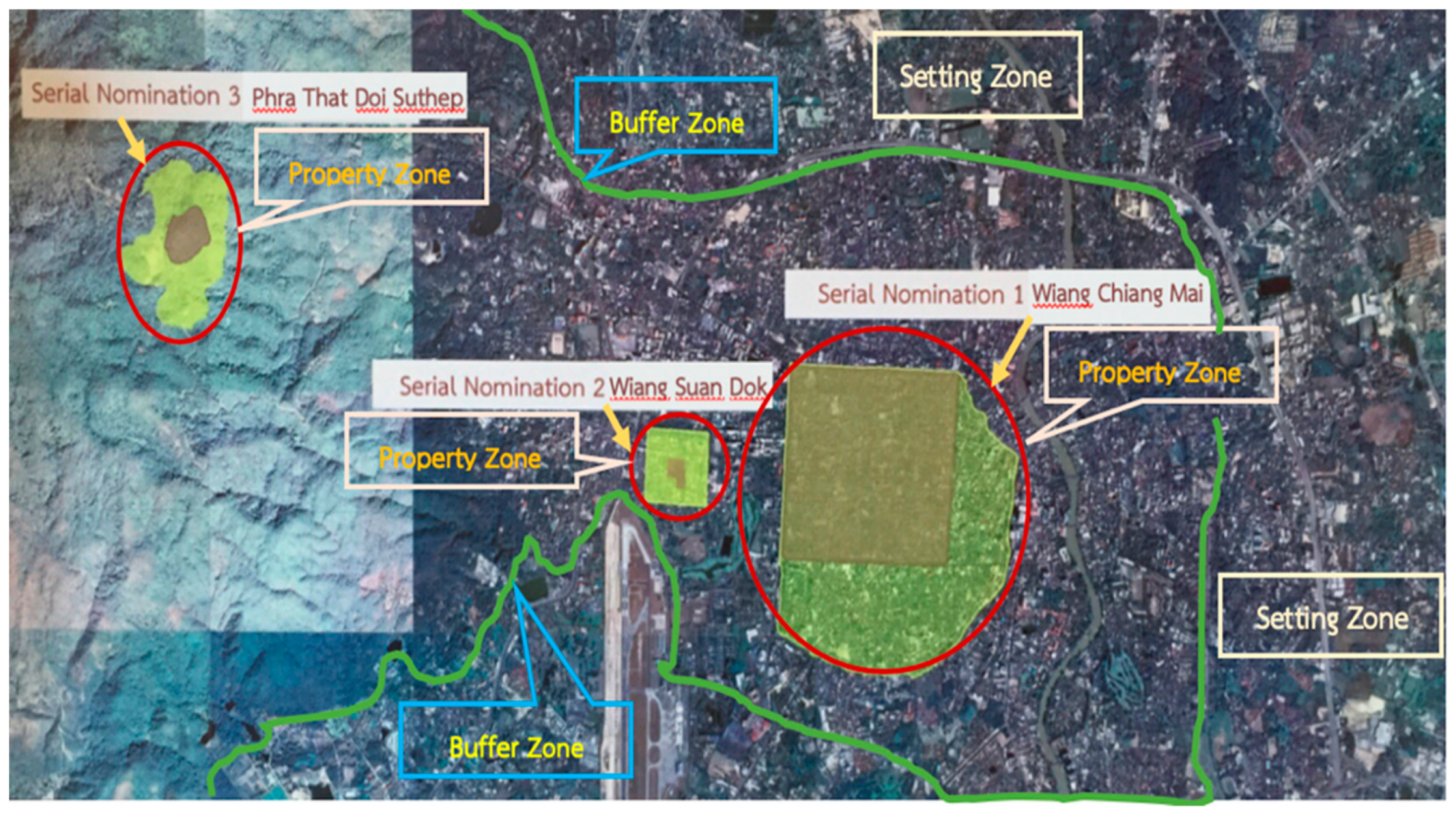

The direction of tourism development in Chiang Mai aims to achieve a balance among society, economy and environment through the conservation of the old city wall, historical area, old town community, areas of belief/spiritual/faith, and green areas/watershed forests, through the inheritance and transfer of culture and urban spirit by government agencies, local government, citizens, networks, communities, private sectors, owners of shops, residences and activities. Chiang Mai supports “Chiang Mai to the World Heritage City” under the concept “Living city”. The development strategy using space-sharing principles (zoning) to divide the area into three zones (

Figure 17). Zone 1 is the Property zone. The World Heritage Area is divided into three areas: Wiang Chiang Mai/Wiang Suan Dok 5.30 km

2, and Phra That DoiSuthep 32.37 km

2. Zone 2 is the Buffer zone, containing surrounding heritage areas and Zone 3 is the setting zone. The surrounding area comprises community areas, districts, and important temples.

This is a place of way of life, communities, and culture. “The story of the world heritage and Chiang Mai is not new but it is a new hope for the people of Chiang Mai. (3) we look backwards as I can remember and find that The effort to push Chiang Mai to be a World Heritage City has existed since 1992 or 37 years before the Chiang Mai Immaculate Conception, (3,6) the 700 year anniversary by the People’s Sector, senior reporters and academics led to propose the initial report to UNESCO. Chiang Mai map was not considered as a Tentative List in accordance with Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage in the early February 2016.”. (3)

Driving development plans is not only good for tourism. To preserve the city of Chiang Mai and its cultural heritage, the history of the city is supported by government agencies, educational institution, civil society and the people in the area in the drafting of heritage area management plans through brainstorming various methods with the city’s residents. They proceeded from the process of knowledge collection about history, architecture, the understanding and interpretation of ancient documents, and knowledge of sociology and ethnicity, including other sciences which are linked to the beliefs of Lanna, in order to ensure Chiang Mai’s original stories are preserved, as they are essential to pass on information to outsiders, so that they also perceive and realize the need for conservation. Although the world has changed over time, the aura of Chiang Mai has not been changed.

This is a sustainable tourism development in Chiang Mai: “Chiang Mai has its own unique identity which is more than 700 years old. (1) It also has a beautiful culture and tradition. If Chiang Mai is a UNESCO World Heritage city, it will become a city that gets more attention from all over the world. This will lead for more social and economic development including and natural resource protection.”. (1,4) “To maintain the balance of natural resources of upstream forests in Doi Suthep which is an important natural water source that lures the lives of people in Chiang Mai” (11).

5.5.2. Urban Tourism Development Framework in Phuket towards Sustainability

The direction of urban tourism development in Phuket town aims to create a balance between society, economy and the environment through the urban conservation of Old Town Phuket through architecture, community lifestyle, local food, and the history of Phuket. In the past, Phuket was a tin mining industry area of two groups of foreigners: Chinese and Westerners. This caused Phuket to develop a multicultural lifestyle, traditions and customs, costumes, languages, local food, and architecture. There was an evolution of houses, commercial buildings, and government buildings with a mixture of cultures called Sino (China)-European (Europe) in accordance with migration and culture adoption [

70,

79,

80,

86]. When the tin mining ended, the area’s economy changed from a mining city to a tourism city. Phuket was well-known due to its tourist attractions, including the sea, beaches and islands. This caused the area to have continuous economic growth and caused a wider relocation of people from the old town communities to the coastal communities.

After that, the importance of the city and its economic prosperity were reduced and tourists know little about the old town in Phuket. “Tourism in Phuket began to be famous from the sea, beaches and islands tourism and was well-known to foreign tourists. Urban Tourism was still not very well-known because, the tourists went to the seaside through bypass road directly from the airport. They did not pass the city areas, so it caused the old economic district of the city to become very sluggish and there were too many relocations and selling of houses and buildings” (2, 7,14,15). Local government and the people in the community were aware of Phuket’s urban regeneration, especially in the old commercial area around Thalang Road or Thalang Community (Talat Yai area) which was extended to connecting areas in the later period. Rehabilitation and development of the old Phuket town (Phuket urban regeneration) started concretely in 1994.

In 1998, information was collected about Phuket town, and its buildings, traditions, food and culture by the local government and central government through various rehabilitation programs. “Conservation and development must be actually based on the history, culture and identity of Phuket. (9) This began to collect data thoroughly which led to the correct preparation of information for tourism. The people in the community must acknowledge and be aware of conservation in the same direction” (13).

The development used the principles of space division or zoning, as in Chiang Mai, but with some differences. The continuation of the Old Town Phuket conservation area started from the center and was not separate like Chiang Mai. The area was divided into three zones [

70] (

Figure 18). Zone 1, is the property zone—the Old Town Phuket conservation area in the center of the city in the Phuket municipality. It was divided into three business districts; Old Town, the Government Center around the foot of Sae Hill and from Bang Niao area to Saphan Hin, with an area of 2.76 sq. Km. Zone 2 is the buffer zone—the area around the Old Town Phuket conservation area and Zone 3 is the setting zone—the surrounding area, comprising the mangrove forest community area, mountains and area of development for various real estate industries. “

The zoning will lead to the protection of the area. It will be easy to maintain, collect information, and do the history and changes of the area in order to provide information to government agencies and tourists’ understanding. Local government ordinance legislation will be operated to control the area in each zone”. (10).

5.6. Participation of Stakeholder for Urban Tourism Development towards Sustainability

The urban tourism development towards sustainability in Chiang Mai and Phuket focuses directly on stakeholders. This includes the residents, local government, community network, private sectors, owners of shops who live and do business in Chiang Mai and Phuket, and indirect stakeholders who do not live in the city area of Chiang Mai and Phuket but have lifestyles and careers which are connected to the city area. The movement for driving sustainable urban tourism development in Chiang Mai and Phuket consists of four procedures (

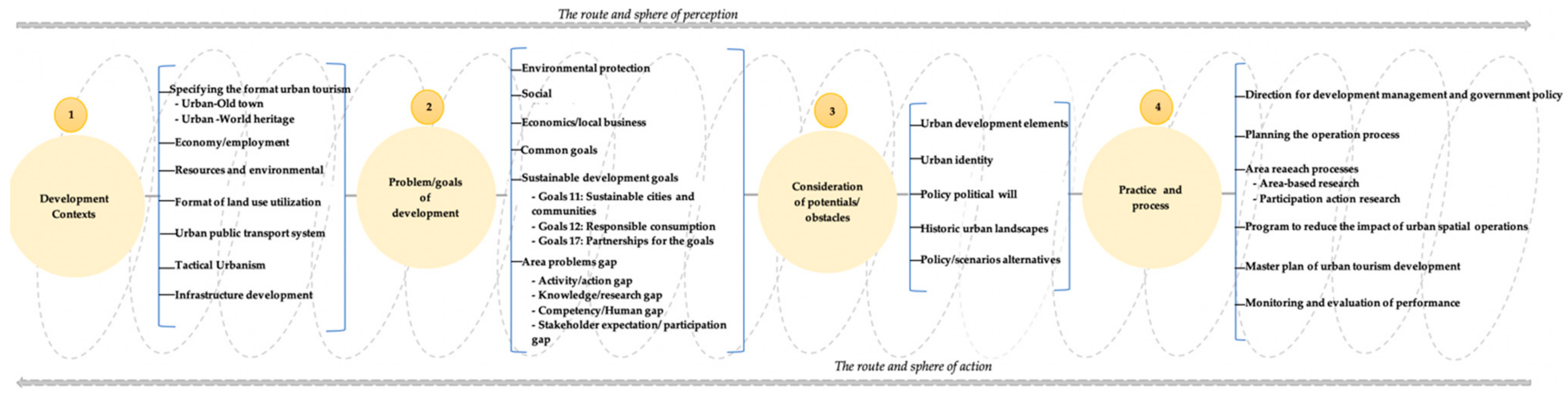

Figure 19) to increase understanding and participation, perceive the problems occurring in the area, and set development goals, considering each area’s context and limitations, which are important to remember when formulating strategies and procedures for implementation.

Procedure 1: Review of the context of area-based development. Stakeholders’ participation in reviewing and specifying the context of area based development of Chiang Mai and Phuket was a result of the central government policy regarding the local governments of Chiang Mai and Phuket, which were two of the 24 cities involved in the preparation of a masterplan for conservation and development in the old city areas of Chiang Mai and Phuket. Although the policy was enforced by the central government (Top-down) with the awareness of all the stakeholders, they emphasized workshop technique to induce participation from other levels (induced participatory action workshop). This involved a combination of top-down development administration approaches (top-down approach), approaches reaching from the bottom to the top (bottom-up approach), and cross-sectoral approaches. This began increase the understanding of stakeholders from all sectors about the urban valuable area development scope (community), in order to ensure the direction of their area-based development was a bottom-up process (bottom-up). They gave precedence to the context of urban and urban tourism development, specifying the format of urban tourism (Old town/World heritage town), economy/employment, resources and environmental impact, the format of land use utilization, the urban public transport system, and tactical urbanism and infrastructures development (water quality, housing planning, wastewater treatment system, etc.).

Procedure 2: Problem Definition and Development Goals. They aimed to build a livable city (city livability) and cities which have the qualities and uniqueness of Chiang Mai and Phuket. This causes them to be aware of the problems the cities are facing, such as an activity/action gap, a knowledge/research gap/competency/local human gap and a stakeholder expectation/participation gap, which led to the determination of the common goal of the area to be "How to make the livable city and the city for all", including issues surrounding environmental protection, social (quality of life) issues and economics/local businesses, with development goals consistent with the sustainable development goals of the UN as follows: Goal 11—Sustainable cities and communities, Goal 12—Responsible consumption, and Goal 17—Partnerships for the goals [

92].

Procedure 3: Consideration of the Capacity and Obstacles of Development. They began to consider the capacity of the area by exploring and understanding the physics and value of the city, including the local human resources, in order to determine the urban identity and urban development and the direction of future development. They considered the support of political policy (policy political will) from the local and central governments, to encourage them to propose policy alternatives based on the capacity of and obstacles facing the area. These were discovered through scenarios analysis, through the participation of urban people (communities), in order to create masterplans based on mutual awareness and a measurement of the true needs of people in the city.

Procedure 4: Practices and Procedures. Our process began with a research process emphasizing area-based research and participation action research (see Procedure 1). The key direct and indirect stakeholders would be required to participate in planning the operation process, the program to reduce the impact of urban spatial operations, and the masterplan of urban tourism development, in order to be consistent with the direction for development management and government policy and the monitoring and evaluation of performance. This responds to the goals of area-based development in Procedure 1.

The four procedure process comprises stakeholders as local governments, government agencies, civil society, private sectors/entrepreneurs, monks, experts in city history, scholars and non-profit groups as the players who need to perceive, comment, and practice (action). The entire process, from Procedure 1 to Procedure 4 would be carried out, and each stakeholder would play a key role in this. The form of stakeholder participation for the determination of the direction of urban and tourism development in Chiang Mai and Phuket arises from the needs and awareness of the area, resulting from tourism activities or other activities which influence both tourists and communities [

22]. Awareness is required awareness to solve the problems and find specific opportunities to manage facilities which are appropriate for people in the community and respond to the needs of tourists. Hence, stakeholders play an important role in determining urban and tourism development goals to reduce the impact of planning and the development of tourism projects on the city and the people who live in the city [

21]. Moreover, city networking and networks among communities, entrepreneurs, and government sectors are important tools for joint development, which will help to strengthen the urban and urban tourism development towards sustainability.

6. Discussion

The results of the study indicated some interesting issues regarding the process of holistic knowledge collection for planning-making for urban and urban tourism development towards sustainability, also known as "Synergy cooperation among stakeholder". Integrated collaboration processes among stakeholder groups-communities, government sectors, private sectors, non-profit organizations and tourists are essential, because urban management should support the creation of a livable city for all, including the people who live in the city. This planning should not preserve the city for tourism marketing only; but the center of planning for urban renewal and conservation is urbanization for people, creating a livable atmosphere and environment and preserving the diverse, traditional ways of life for residents. Hence, the actual participation of stakeholders in the formulation of maps begins with the area, which will lead to building a city with the potential to be a livable and a destination city. This will lead to stable resources, culture, environment, and quality of life for citizens, including security of life and the property of tourists, drawn to the essence of Chiang Mai and Phuket.

In fact, an overview of Thailand, including Chiang Mai and Phuket, does not evidence plans and methods to assess the sustainability of the city, because there are changes in the tourism situation in Chiang Mai and Phuket, resulting in economic growth, and changes in social conditions and urban environment. There has been no mention about the role of vulnerable and marginalized groups in the urban society in discussions of development, to ensure they benefit from the growth of urban tourism, as the number of tourists has been increased significantly. This is consistent with policies and strategies to stimulate urban tourism, which emphasize the competitiveness of urban services (economy) as their first priority, although they are starting to change the direction of policy development, beginning to reduce the negative impact on housing, and the urban development without direction (urban sprawl) that Thailand is currently facing.

On the one hand, the sustainable urban tourism development, in the case of Chiang Mai and Phuket, has many important, related aspects, especially politics and bureaucratic structure, which are important factors for urban and urban tourism development in Thailand (Urban Tourism in Thailand) that lack policy development and continuity of policies from the central and local government over a short period (three years, five years). This is a difficult to change structure which is needs to improve and change to prevent the negative impacts of tourism. Lack of comprehensive decentralization for local governments causes the area-based administration to face legal, power, command and regulation limitations. Moreover, there is a lack of data, information, and holistic integration of policy formulation and development plans that specify project and activity. There is also no budget allocation that covers and is enough for the area’s operation, causing the city to cease development (urban development disruption).

Therefore, crossing the sustainability gap of urban and urban tourism development in Chiang Mai and Phuket through (

Figure 16) the development of a capacity assessment system for handling the environmental impact of carbon emissions, energy uses, waste management, wastewater treatment system, and the number of green spaces in the city is important. This involves the monitoring and collection of data about the impact of urban tourism. Data is publicized broadly and can be easily understood by increasing the public spaces for comment (urban space and urban talk) so that there is a space to listen to the voices of the people who live in the city (every group in the society can express their opinions openly and access conveniently). This would include tourists, training and facilitation, operation technics, and stakeholders, to assist in knowledge building and help create an innovative system, which focuses on solving the problems of the specific sustainability of the city and the determination of tourism activities as responsible economic activities which realize the social responsibility of hospitality and the tourism industry in the city. This would ensure a return to a society which increases the value and identity of the city, as well as changing aspects which have a negative impact on the economy and local employment rates. Although the power structure and administration of the bureaucratic system have not been able to change entirely, the people in the city and the tourists can drive the urban and tourism development with their own heart and the consciousness.

7. Conclusions

In summary, the form and procedure development process of urban tourism in Thailand towards sustainability found that there was a complex relationship of the society, economy and environment in the city. Complex problem solving of complexity must involve collaboration with all stakeholders, including tourists, to determine the direction of urban area based development. This must not only focus on urban preservation, but also include integration processes of policy/plan, mission, and budget, which are linked to the whole system and will lead to the sustainability of the city. The main components of this are communities, buildings, houses, cultural heritage, the urban landscape, trade, investment, and tourist services in Chiang Mai and Phuket. Important factors for conservation and integration, stretch from the foundation and importance of the city, to city design and consistent planning by collecting and storing data to increase urban awareness and the expectations of tourists (

Figure 16).

Analysis and synthesis do not delve into the idea base, methods or indicators of sustainability in the social and economic environment, or history and culture of the city, but the author would like to suggest the Urban Tourism Development Planning Driving Framework towards sustainability, based on these case studies of Thailand. This begins with stakeholder participation through analysis and synthesis of the cities’ values and capacity, urban development needs, problems of urban development, and the procedures of the stakeholders, because the solution and prevention of negative environmental, social, and economic impacts should be integrated into policies, strategies and practices relating to natural resource management, cultural resources and social equality objectives. These range from increasing awareness of the origin of Chiang Mai and Phuket to an overview of Thailand that needs to be acknowledged and applied via recommendations from the area in both qualitative and quantitative ways. It also provides possible recommendations for specification and formulation of national and local policy development frameworks. The work presents an area-based driving model that is easy to understand and apply (

Figure 19).

In addition, we summarize and develop the conceptual base model of Thailand’s urban tourism development (

Figure 16), through the presentation of ideas and empirical data to the public in order to disseminate thought processes and integrated methods. It will be useful to begin the area-based development process to policy formulation with a bottom-up approach, which will benefit the urban tourism development towards sustainability.