The Effect of the Corporate Social Responsibility of Franchise Coffee Shops on Corporate Image and Behavioral Intention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility

2.2. Corporate Image

2.3. Behavioral Intention

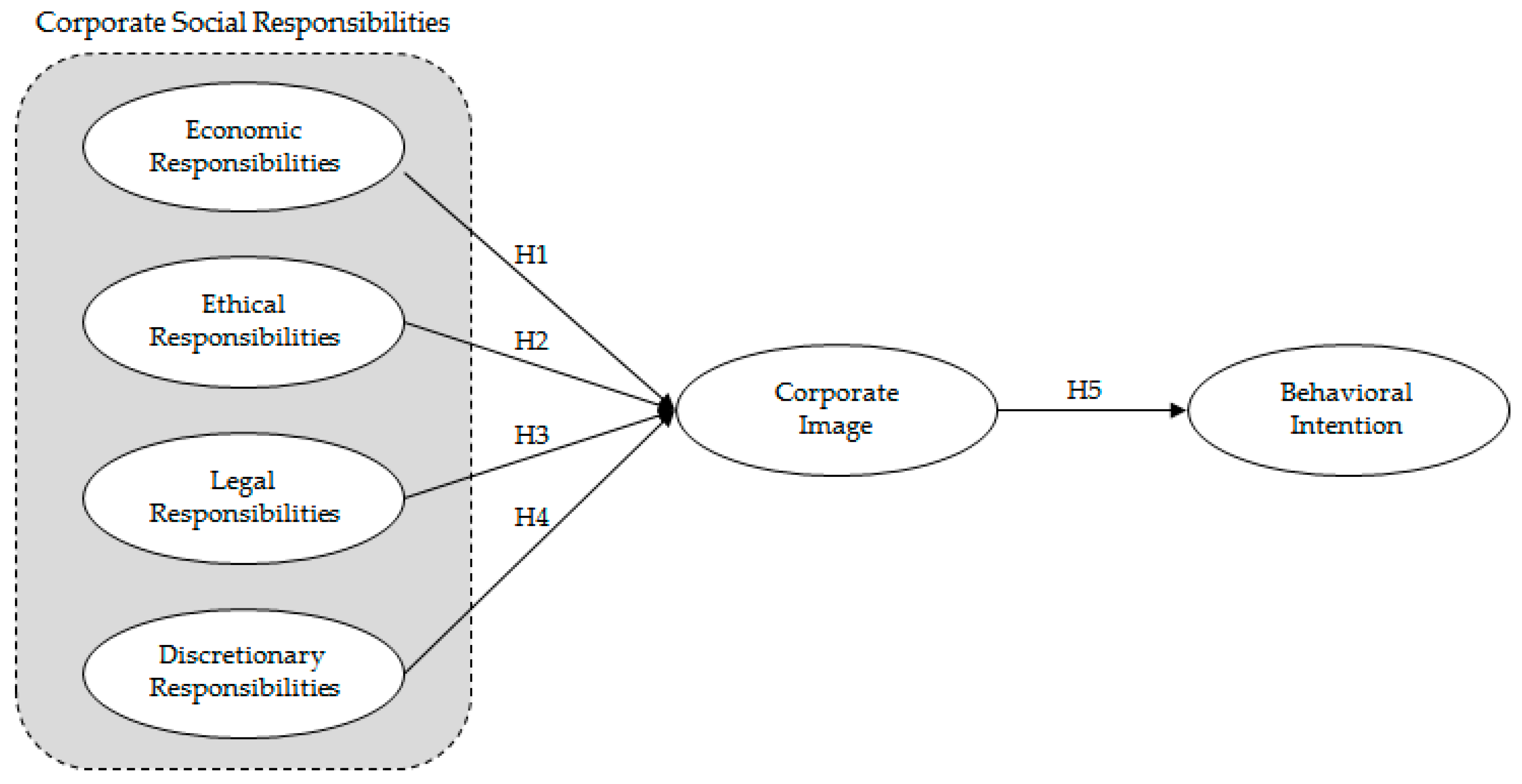

2.4. The Research Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Participant Characteristics

3.2. Measurement Scales

4. Results

4.1. Reliability, Validity, and Common Method Bias

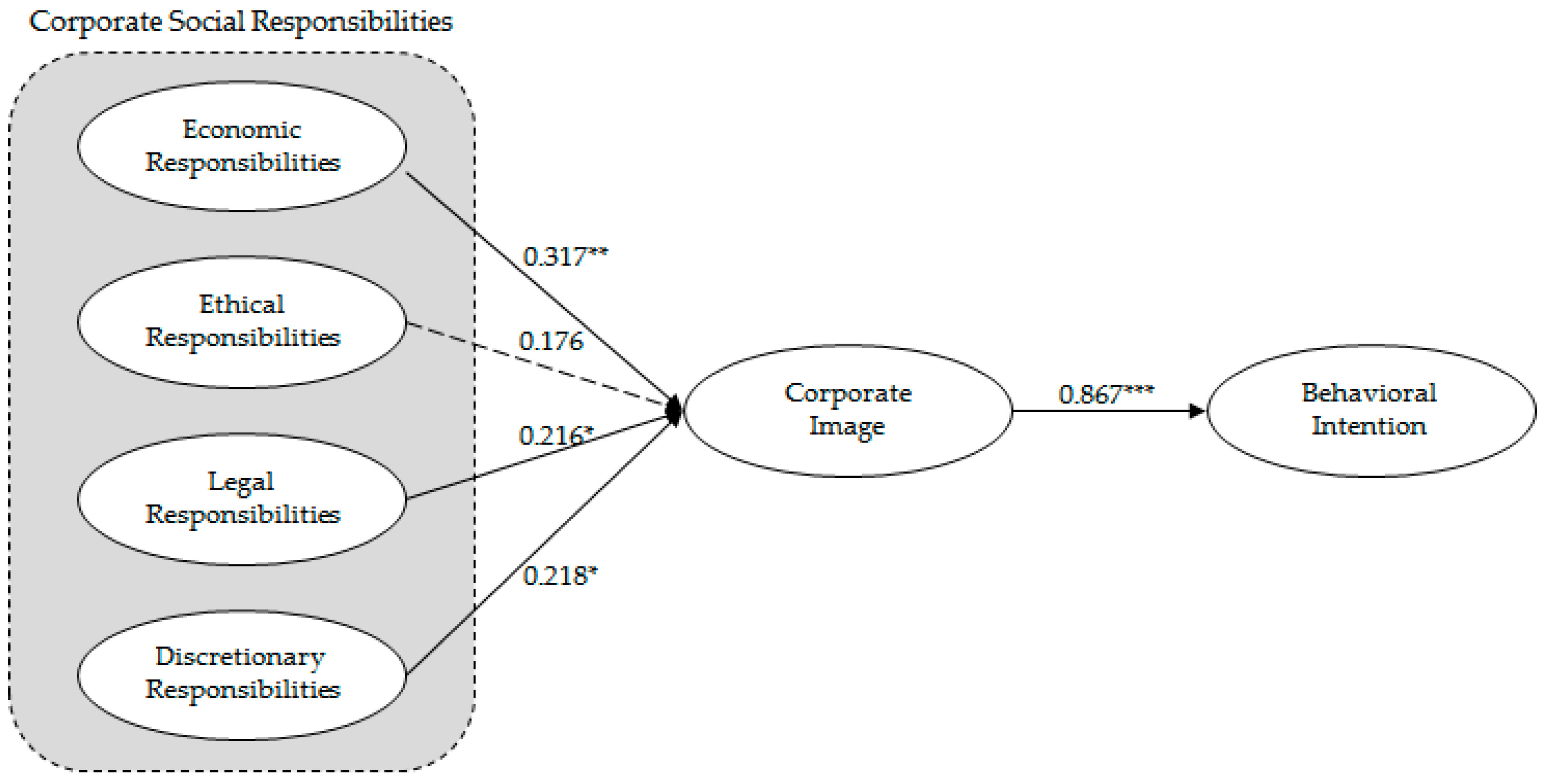

4.2. Hypothesis Test

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

References

- Korea Customs Service Report. 2016 Coffee Import Status. 2017. Available online: http://www.customs.go.kr/kcshome/cop/bbs/selectBoard.do?layoutMenuNo=294&bbsId=BBSMSTR_1018&nttId=3899 (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Kim, H.M.; Cha, S.B. The analysis of customers’ price sensitivity of Americano in Roastery Coffeehouses. J. Tour. Sci. 2013, 37, 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Sunday Seoul Daily Newspaper Home Page. Available online: http://www.ilyoseoul.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=216667 (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Barone, M.J.; Miyazaki, A.D.; Taylor, K.A. The influence of cause-related marketing on consumer choice: Does one good turn deserve another. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.R.; Johnson, F.E. Social Responsibility of the Businessman; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Conference on Trade; Conférence des Nations Unies sur le commerce et le développement; United Nations Conference; Development Staff. Economic Development in Africa: Trade Performance and Commodity Dependence; United Nations Publications: Herndon, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kolk, A. Corporate social responsibility in the coffee sector: The dynamics of MNC responses and code development. Eur. Manag. J. 2015, 23, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starbucks Homes Page. Available online: http://www.starbucks.com/responsibility (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- The Federation of Korean Industries. FKI Issue Paper: 2016 CSR Report. 2016. Available online: http://csr.fki.or.kr/issue/csr/data/list.aspx (accessed on 31 October 2018).

- Lee, S.M. The social construction of the East Asian corporate social responsibility: Focused on global economic recession. Korean J. Sociol. 2012, 46, 141–176. [Google Scholar]

- Alpert, F.H.; Kamins, M.A. Pioneer brand advantage and consumer behavior: A conceptual framework and propositional inventory. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1994, 22, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Shin, S.H.; Kim, S.J. The influence of consistency and distinction attribution of corporate’s cause-related behavior on attitude toward corporate. Korean J. Consum. Advert. Psychol. 2015, 6, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, K.W.; Jin, Y.J. The Influence of the CSR Type on Corporate Reputation, Social Connectedness, and Purchase Intention: An Empirical Study of University Students. Korean J. Advert. 2008, 19, 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Assael, H. Consumer Behavior and Marketing Action, 6th ed.; South-Western Pub: Nashville, TN, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, J.K.; Paterson, L.T.; Stuffs, M.A. Consumer perceptions of organizations that use cause related marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1992, 20, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, C. Corporate Social Responsibilities; Wadsworth Publishing Company: Wadsworth, OH, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Doh, E.J. The strategy of philanthropy for Korean companies. POSRI Bus. Econ. Res. 2005, 5, 203–229. [Google Scholar]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Corporate citizenship as a marketing instrument: Concepts, evidence and research directions. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 35, 457–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumwright, M.E. Company advertising with a social dimension: The role of noneconomic criteria. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, P.R.; Menon, A. Cause-related marketing: A coalignment of marketing strategy and corporate philanthropy. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creyer, E.H.; Ross, W.T. The influence of firm behavior on purchase intention: Do consumers really care about business ethics? J. Consum. Mark. 1997, 14, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, P.; Kline, S.; Dai, Y. Corporate social responsibility practices, corporate identity, and purchase intention: A dual process model. J. Public Relat. Res. 2005, 17, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.I.; Choi, H.S. The relation between corporate social responsibility and financial performance. Korean J. Bus. Adm. 2010, 23, 633–648. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.Y.; Lee, H.R.; Kim, J.M. Effects of corporate social responsibility on company-consumer identification, consumer’s attitude and repurchase intention: Focusing on national coffee franchise. Korean J. Tour. Res. 2011, 26, 239–260. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.I.; Lee, S.H. The effects of corporate social responsibilities of foodservice industry on consumer trust and behavioral intention. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 25, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, T.H. Investigating the influence of corporate philanthropy by franchise coffee brands on corporate image, brand attitude, and behavior intension: The case of Starbucks. J. Tour. Sci. 2016, 40, 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization Home Page. Available online: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/standards/iso26000.htm (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Davis, K. Can business afford to ignore social responsibilities? Calif. Manag. Rev. 1960, 2, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrick, W. The growing concern over business responsibility. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1960, 2, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J. Business and Society; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Falck, O.; Heblich, S. Corporate social responsibility: Doing well by doing good. Bus. Horiz. 2007, 50, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartick, S.L.; Cochran, P.L. The evolution of the corporate social performance model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eells, R.S.F.; Walton, C.C. Conceptual Foundations of Business; RD Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, S.P. Dimensions of corporate social performance: An analytical framework. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1975, 17, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkus, E., Jr.; Robert, B.W. A model of the socially responsible decision-making process in marketing: Linking decision makers and stakeholders. Am. Mark. Assoc. 1992, 3, 154–161. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, M.O.; Shin, J.I.; Chung, K.H. The Relationship among the factors of corporate social responsibility, corporate image, relationship quality, and customer loyalty. Korea Nonprofit Res. 2008, 7, 161–202. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, K.B.; Vogel, C.M. Using a hierarchy-of-effects approach to gauge the effectiveness of corporate social responsibility to generate goodwill toward the firm: Financial versus nonfinancial impacts. J. Bus. Res. 1997, 38, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelman, J.M.; Arnold, S.J. The role marketing actions with a social dimension: Appeals to the institutional environment. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barich, H.; Kotler, P.A. Framework for marketing image management. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1991, 32, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, B.B.; Levy, S.J. The product and the brand. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1955, 33, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, R.O. The nature of corporate images. In The Corporation and Its Publics; John, W.R., Jr., Ed.; John Wiley & Sone: New York, NY, USA, 1963; pp. 24–47. [Google Scholar]

- Enis, B.M. An analytical approach to the concept of image. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1967, 9, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristol, L.H., Jr. Why develop your corporate image? In Developing the Corporate Image; Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1960; pp. xiii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, K.G. Whatever happened to image? Bus. Q. 1970, 35, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R. The measurement of corporate images. In The Corporation and Its Publics; John, W.R., Jr., Ed.; John Wiley & Sone: New York, NY, USA, 1963; pp. 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pharoah, N. Corporate image research in the brewing industry or from red revolution to country goodness in ten years. J. Mark. Res. Soc. 1982, 24, 240–256. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.J. Reputation: Realizing Value from the Corporate Image; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, J.R. Marketing corporate image. In The Company as Your #1 Product; NTC Business Books: Lincolnwood, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, R.N.; Drew, J.H. A multistage model of customers’ assessments of service quality and value. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C. A national customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Fornell, C. A framework for comparing customer satisfaction across individuals and product categories. J. Econ. Psychol. 1991, 12, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L.; Desarbo, W.S. Processing of the satisfaction response in consumption: A suggested framework and research propositions. J. Consum. Satisf. Dissatisfaction Complain. Behav. 1989, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen, T.W.; Lindestad, B. Customer loyalty and complex services: The impact of corporate image on quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty for customers with varying degrees of service expertise. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1998, 9, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, L.C. The effect of brand advertising on company image: Implications for corporate advertising. J. Advert. Res. 1986, 26, 58–81. [Google Scholar]

- Marken, G.A. Corporate image: We all have one, but few works to protect and project it. Public Relat. Q. 1990, 35, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.J.; Ju, S.H.; Xu, Y.Z. The impact of image and attitude toward the Ad on Chinese consumers’ digital camera brand attitude. J. Mark. Manag. Res. 2014, 19, 44–65. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, G.R. Creating corporate reputation. In Identity, Image and Performance; Oxford Univ. Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 25–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, H.M. The structural relationship among consumer perception, corporate, image, brand image and loyalty on corporate philanthropy of foodservice firm: Focused on the fit. J. Foodserv. Manag. Soc. Korea 2015, 18, 215–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesely: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Manfredo, M.J. A theory of behavior change. Influ. Hum. Behav. 1992, 24, 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Boulding, W.; Kalra, A.; Staelin, R.; Zeithaml, V.A. A dynamic process model of service quality: From expectations to behavioral intentions. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Park, H.J. A Study on the differences of family restaurant selection attributes and behavioral intention by lifestyle. J. Foodserv. Manag. Soc. Korea 2011, 14, 125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.S. A Study on Chinese customers’ selection attribute and their behavioral intention at coffee shop: Focusing on the comparative analysis by frequency and purpose of visit. J. Hotel Resort 2013, 12, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S. The role of corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Greening, D.W. Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 658–672. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, S.; Kahn, B.E. Corporate sponsorships of philanthropic activities: When do they impact perception of sponsor brand? J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Yoon, H.H. The influence of corporate social responsibility of family restaurants on image, preference and revisit intention: Based on the university students in Seoul. Korean J. Culin. Res. 2008, 14, 138–152. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; Liedtka, J. Corporate social responsibility: A critical approach. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, N. Marketing with a passion. Sales Mark. Manag. 1994, 146, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Carringer, P.T. Not just a worthy cause: Cause-related marketing delivers the goods and the good. Am. Advert. 1994, 10, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Caudron, S. Forget image: It’s reputation that matters. Ind. Week 1997, 3, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Alcorn, D. Cause marketing: A new direction in the marketing of corporate social responsibility. J. Consum. Mark. 1991, 8, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S.; Mohr, A.L.; Webb, D.J. Charitable programs and the retailer: Do they mix. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reaction to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.; Goldsmith, R.E. Corporate credibility’s role in consumer attitudes and purchase intentions when high versus a low credibility endorser is used in the ed. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, R. The role of corporate associations in new product evaluation. Adv. Consum. Res. 2000, 27, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.W.; Namgung, Y. The effects of self-congruity and functional congruity on brand attitude and behavioral intention in the coffee shop industry. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2013, 22, 233–252. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.J. The relationship among culture marketing of coffee shop franchises, brand image and brand loyalty. GRI Rev. 2013, 15, 157–183. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.C.; Kim, K.J.; Lee, H.J. Developing a scale for measuring the corporate social responsibility activities of Korea corporation: Focusing on the consumers’ awareness. Asia Mark. J. 2010, 12, 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommendation two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medsker, G.J.; Williams, L.J.; Holahan, P.J. A review of current practices for evaluating causal models in organizational behavior and human resources management research. J. Manag. 1994, 20, 439–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Cameron, G. Conditioning effect of prior reputation on perception of corporate giving. Public Relat. Rev. 2006, 32, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | λ | α | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Responsibilities | The product quality (or service) seems to be improving constantly. | 0.524 | 0.695 | 0.775 | 0.465 |

| Seems to have a system that reacts to customer complaints. | 0.644 | ||||

| Contributes to national economic growth through profit maximization. | 0.569 | ||||

| Puts much effort into employment. | 0.686 | ||||

| Ethical Responsibilities | Has high overall ethics standards and protocols. | 0.683 | 0.814 | 0.855 | 0.596 |

| There are no excessive ads or false ads. | 0.641 | ||||

| Conducts transparent business. | 0.699 | ||||

| Carries out fair transactions with business partners. | 0.691 | ||||

| Legal Responsibilities | Products meet legal standards. | 0.693 | 0.834 | 0.870 | 0.626 |

| Contributes to social welfare systems as mandated by law. | 0.770 | ||||

| Seems to fulfill the responsibilities indicated on their contracts with other partners. | 0.771 | ||||

| Management seems to put effort into ethical business management, complying with the product related regulations. | 0.754 | ||||

| Discretionary Responsibilities | Encourages collaboration of business with the regional community and other institutions. | 0.765 | 0.819 | 0.863 | 0.612 |

| Sponsors sports and cultural events. | 0.693 | ||||

| Encourages charity services supporting regional communities. | 0.705 | ||||

| Gives back to society. | 0.712 | ||||

| Corporate Image | Have good impressions of the company. | 0.766 | 0.914 | 0.924 | 0.671 |

| Perceive the company in a positive way. | 0.757 | ||||

| I like the company. | 0.854 | ||||

| The company is trustworthy. | 0.802 | ||||

| The company puts much effort into customer satisfaction. | 0.736 | ||||

| The company is an excellent company. | 0.802 | ||||

| The company is beneficial to society. | 0.742 | ||||

| Behavioral Intention | I will try to revisit the shop. | 0.785 | 0.907 | 0.919 | 0.654 |

| This company will be on my priority list. | 0.828 | ||||

| I will still visit the brand even if their prices increase. | 0.710 | ||||

| I will come to this brand even if there is another brand nearby. | 0.833 | ||||

| I will provide positive comments about this brand to others. | 0.857 | ||||

| I will actively recommend this brand to my family or acquaintances. | 0.830 | ||||

| χ2(302) = 252.131; p > 0.05, GFI = 0.944, AGFI = 0.920, NFI = 0.955, RFI = 0.935, TLI = 1.000, CFI = 1.000, RMSEA = 0.000, RMR = 0.023 | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Economic Responsibilities | 0.465 | |||||

| 2. Ethical Responsibilities | 0.560 ** | 0.596 | ||||

| 3. Legal Responsibilities | 0.571 ** | 0.638 ** | 0.626 | |||

| 4. Discretionary Responsibilities | 0.524 ** | 0.533 ** | 0.617 ** | 0.612 | ||

| 5. Corporate Image | 0.613 ** | 0.634 ** | 0.657 ** | 0.571 ** | 0.671 | |

| 6. Behavioral Intention | 0.521 ** | 0.552 ** | 0.593 ** | 0.527 ** | 0.806 ** | 0.654 |

| Mean | 3.074 | 2.961 | 3.115 | 2.782 | 3.134 | 3.008 |

| SD | 0.594 | 0.647 | 0.712 | 0.665 | 0.726 | 0.797 |

| Hypotheses | Standardized Coefficient | SE | CR | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 Economic Responsibilities → Corporate Image | 0.317 ** | 0.132 | 3.134 | Supported |

| H2 Ethical Responsibilities → Corporate Image | 0.176 | 0.115 | 1.737 | Not Supported |

| H3 Legal Responsibilities → Corporate Image | 0.216 * | 0.119 | 1.974 | Supported |

| H4 Discretionary Responsibilities → Corporate Image | 0.218 * | 0.106 | 2.362 | Supported |

| H5 Corporate Image → Behavioral Intention | 0.867 *** | 0.075 | 12.936 | Supported |

| χ2(308) = 234.668; p > 0.05, GFI = 0.947, AGFI = 0.925, NFI = 0.955, RFI = 0.941, TLI = 1.000, CFI = 1.000, RMSEA = 0.000, RMR = 0.022 | ||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cha, J.-B.; Jo, M.-N. The Effect of the Corporate Social Responsibility of Franchise Coffee Shops on Corporate Image and Behavioral Intention. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236849

Cha J-B, Jo M-N. The Effect of the Corporate Social Responsibility of Franchise Coffee Shops on Corporate Image and Behavioral Intention. Sustainability. 2019; 11(23):6849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236849

Chicago/Turabian StyleCha, Jae-Bin, and Mi-Na Jo. 2019. "The Effect of the Corporate Social Responsibility of Franchise Coffee Shops on Corporate Image and Behavioral Intention" Sustainability 11, no. 23: 6849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236849

APA StyleCha, J.-B., & Jo, M.-N. (2019). The Effect of the Corporate Social Responsibility of Franchise Coffee Shops on Corporate Image and Behavioral Intention. Sustainability, 11(23), 6849. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236849