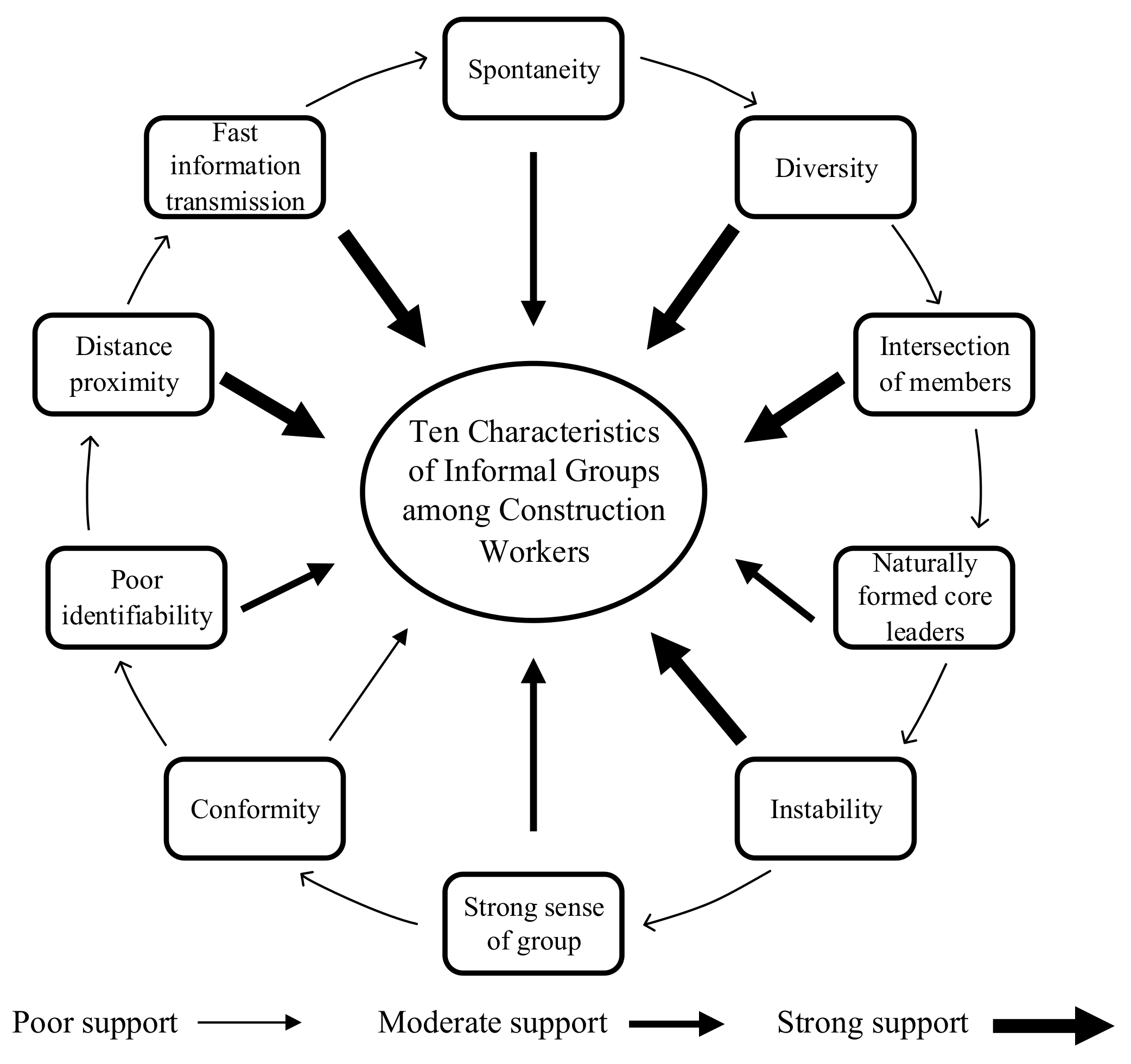

4.1. Types of IGCWs

As is shown in

Figure 4, five subcategories of types were initially identified, and the number decreased. Generally, kin groups and geopolitical groups were formed when workers came to a site, while hobby groups, friendship groups, and interest groups were formed after that. As Barnard has indicated, informal organizations are formed in two ways: spontaneously before formal organizations come into being or spontaneously after that based on normal operations [

8]. A detailed analysis of the five subcategories is presented in the following paragraphs.

4.1.1. Geopolitical Groups

There is no doubt that geopolitical informal groups were the most common among Chinese construction workers. Almost all of the interviewees expressed that workers came out to work at the construction sites together with other villagers. As Worker I-1 revealed, there were many of his fellow villagers at the construction site, either from a village or a town. In addition, the majority of workers stated that their boss was from their home region: they came to the site with the boss. Manager II-1 responded that there exists such a phenomenon in the Chinese construction industry. Namely, first, the workers go to the construction site with a boss from the same town. Then, if the construction site still lacks workers, the boss will ask the workers to introduce him/her to people they know. Most of these people are from their hometown. In short, geography is the premise and root of the formation of groups of construction workers. The expansion of construction workers groups and the formation of other types of informal groups are all based on geographical groups. Geo-features are a synonym for Chinese construction workers.

4.1.2. Kin Groups

It was also very common for construction workers to have their own relatives at the site. One reason, revealed by Worker III-4, was that when men come to construction sites to work, their wives follow because they cannot grow crops by themselves. Manager V-1 pointed out that it is quite widespread for a husband and wife to work together in bricklaying and plastering. This is less common in other types of work due to restrictions in the nature of the work. As was demonstrated by Manager IV-1, most jobs on construction sites are not suitable for women workers. Nevertheless, Manager III-2 also indicated that as long as the workers are willing to bring their wives, they will try to arrange work. As a result, husband–wife relationships abound at the sites. In addition, a son following his father to a construction site to learn some technical skills is now the main way to absorb the new generation of labor force in the construction industry. Manager V-1 responded that there had been a shortage of workers in recent years, with few workers onsite post-1990s. Worker II-2 also stated that young people prefer to go to factories rather than to construction sites because they think it is too hard. In other words, as long as there are relatives in the family who engage in the construction industry, wherever there is work to be done, relatives are called in whenever possible. For example, Worker IV-4 emphasized that he had come to the construction site with his three brothers. In other words, various close and distant family relationships exist at the sites, such as couples, brothers, and cousins.

4.1.3. Hobby Groups

Because of the limitations of their working environment, workers have few activities in their spare time. Worker III-2 expressed that he goes to work at 07:00, gets off work at 18:00, and has to get up at 6:00 in the morning every day. In addition, Worker V-2 said, “I work about 10 hours a day, and if the schedule is tight, I may work overtime in the evening.” The response of managers also confirmed this point. Worse, there are few recreational facilities built on the site, and workers cannot relax when they are free, as Worker IV-3 indicated. Thus, the group activities that appear the most at construction sites are eating and drinking and playing mahjong (a game of chance for four players that originated from China) or cards. Particularly, manager V-2 manifested that when it was time to leave work, several workers who liked drinking would meet for dinner. Worker I-1 also stated that eating and drinking were the conditions that brought the workers together the most because they are quite tired after a day’s work and do not have much energy to do other activities, as was expressed by Worker IV-1. A mahjong or cards group is another informal group that exists among construction workers. They either play poker in the bedroom or play mahjong in the mahjong hall. However, some interviewees said the activity is rare at construction sites. Responses such as “the happiest thing every day is to fall asleep in bed”, “I often play on my mobile phone during the break”, and “the workload during the whole day is too heavy and very tiring” were obtained. However, some participants also demonstrated that workers who like playing mahjong or cards get together as much as possible whenever they have free time. For example, Worker IV-2 indicated that if he had a rest the next day and did not have to work, he would make an appointment with his workmates to play mahjong. Worker III-3 and Manager V-1 both emphasized that some workers will go to play mahjong when there is no water or electricity on the site or when the rain makes it impossible to work. It is worth mentioning that a fee-paying mahjong parlor was set up on the site for workers’ entertainment, according to Manager V-1.

4.1.4. Friendship Groups

The majority of workers are completely willing to make friends (based on the responses of the participants). They make a few good friends with whom they can talk onsite, as was revealed by Worker II-3. Worker III-3 also suggested that friends are a must when you are away from home. As is well-known, everyone has their own personality characteristics. Similar workers thus naturally flock together to form a friendship-type informal group. An example was cited by Worker IV-4: “Workers of a comparable age usually get together and talk more.” In addition, construction workers come to the sites for the simple purpose of doing their own work. There is not much suspicion and defensiveness between them, which allows them to make friends more quickly in a short time. Thus, friendship-type informal groups are widespread among construction workers, and they often gossip over teacups at the break as well as help each other in times of need. More importantly, Worker V-6 pointed out that the more friends you make, the more job opportunities you have. That is, if you have a lot of friends who work in the construction industry, they will recommend you when there is a vacancy at their construction site.

4.1.5. Interest Groups

In the Chinese construction industry, there is a kind of pervasive interest-type informal group. This is commonly known as “small subcontracting”. Manager I-1 indicated that “small subcontracting” means that several workers organize together to complete a certain amount of work designated by Party A. Accordingly, there is an organizer in this small group who assembles members to complete the subcontracting task and hand over to Party A. After the workers complete the task together, Party A will pay money to the organizer, and then the workers will divide up the money together. Worker V-2 presented that these members are basically composed of relatives, friends, or fellow villagers, which greatly reduces the conflicts of interest. An example was raised by Manager II-1: “When Party A has a tight demand for time and a relatively high price, an interest informal group can be formed quickly, such as putting up canopy.” Another example, cited by Worker III-5, was that they often organize masons to contract the building of a wall, and then the boss calculates the amount for them. Other types of work, such as supporting formwork, binding steel, and plastering, all exist within “small subcontracting”. In addition, there is also a sort of interest group on the site occasionally. Several workers will immediately form a group to cause trouble in the project department if they are not paid on time or for other reasons, namely “claiming back salaries”. Manager III-2 illustrated that sometimes extreme measures are taken, such as blocking doors or roads and pulling banners. At this time, a key point was raised by Manager II-1, “Sharing a bitter hatred for the enemy is perfectly reflected among workers.” There are basically no other interest groups among the workers, given the responses of almost all interviewees.

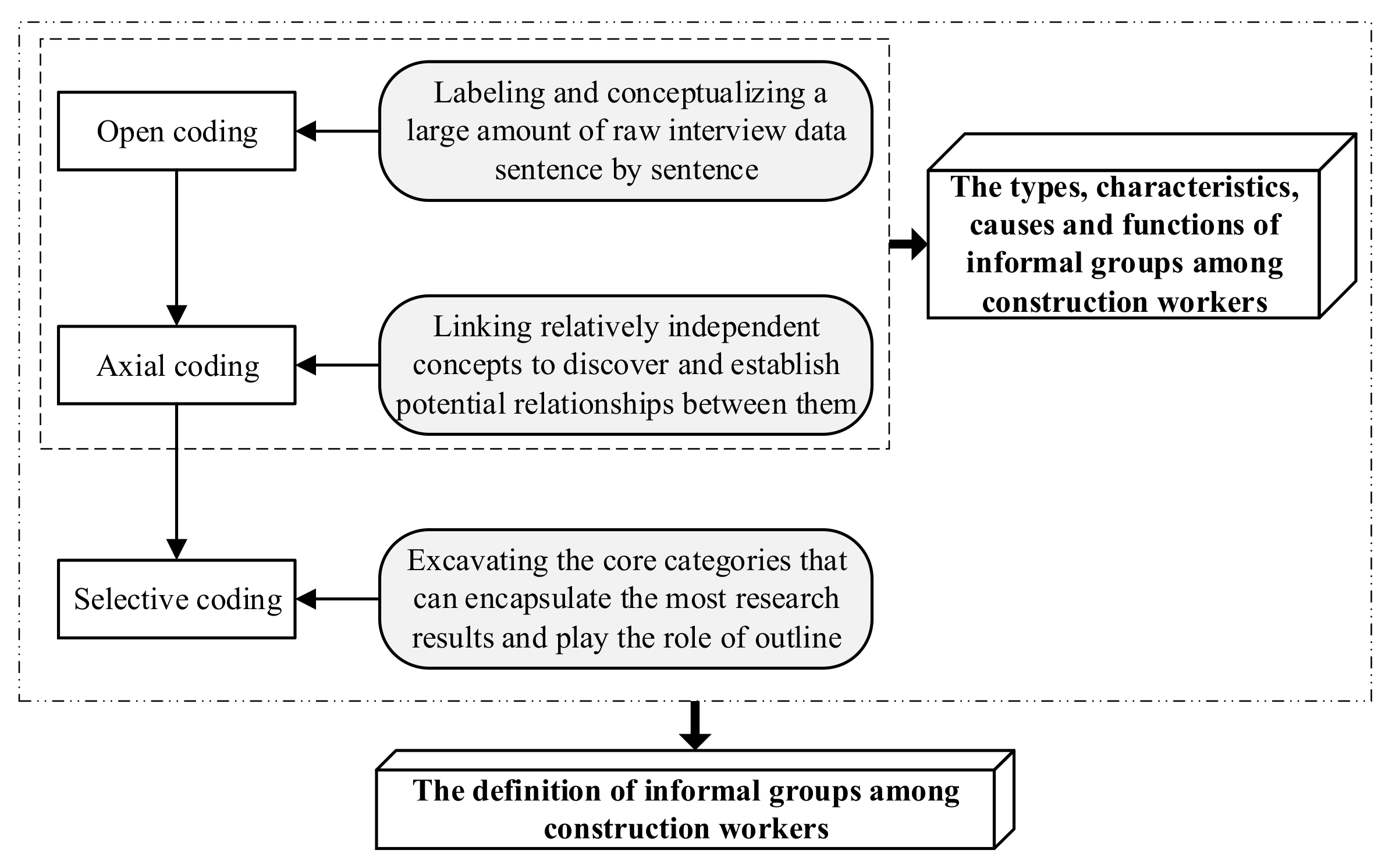

4.2. Characteristics of IGCWs

According to the interview data, 10 characteristics were encoded based on grounded theory, and the support strength of the characteristics was calculated, as shown in the

Figure 5. We evaluated supportive strength as follows: strong support, where more than 75% of interviewees responded; moderate support, where 50–75% of interviewees agreed; and poor support, where less than 50% of interviewees agreed [

48].

First, like employee groups in most industries, IGCWs are characterized by spontaneity and diversity. Construction workers spontaneously form informal groups without the approval of the organization and a clearly defined formal structure. Moreover, there are various informal groups, as is described in

Section 4.1. Second, members of informal groups intersect, that is, a worker may join several types of informal groups. Among construction workers, the intersection between interest informal groups and the other four groups was particularly obvious. In other words, geography, kinship, hobby, and friendship are the premise and foundation of the formation of interest groups. Seven other features are detailed in the following paragraphs.

4.2.1. Naturally Formed Core Leaders

Managers and workers who participated in the interview alike said there are always “petty leaders” in the informal groups where workers are located. The members of informal groups are very convinced by them and listen to them. In particular, as was revealed by Manager II-1, there are several informal leaders when a crew of workers is large, while the “petty leaders” and the foreman are usually the same person when there are fewer workers. It is worth mentioning that there are many reasons why some workers can become informal leaders. One of the most immediate reasons indicated by the majority of workers was, “He brought me to work on this construction site, so I must listen to him.” In other words, the respondents reported that the worker who introduces them to the job often becomes the informal leader he believes in. As Manager III-2 expressed, the “petty leaders” who workers trust can bring them benefits and help, at the very least. Moreover, responses such as the following were mentioned: “the chief attribute of petty leaders is their ability to find work and look for workers”; “petty leaders usually know a lot of bosses, have resources, and the boss trusts them”; “it is necessary to have affinity and be considerate to informal leaders”; “being infectious, being very talkative, and team management ability are extra points”; and “they have long working hours and rich experience and are known as veterans, and these are reasons why someone can be a ‘petty leader’”. This implied that different types of “petty leaders” can be created for different reasons at construction sites. For someone to become an informal leader, he must have a lot of traits. Accordingly, Manager I-1 added that some informal leaders with the above features will gradually become a formal foreman after a period of time: at the beginning, he is convinced by the workers because of some virtues or idiosyncrasies, and gradually he takes a group of workers to pick up the work, thus becoming the leader of the construction crew. Worker V-4 confirmed that standpoint. He emphasized that people who were charismatic and had construction workers under them in the 1980s and 1990s are now basically bosses.

4.2.2. Instability

The instability of informal groups is particularly evident in the construction industry. Unlike factories, construction projects are temporary, and members of informal groups are bound to change after a project is completed. Moreover, construction workers are highly mobile, and workers in different jobs are rotated as the project progresses. This results in members of informal groups being in constant flux. Worker V-1 demonstrated that new workers can quickly integrate into a collective and form their own friendships, hobby groups, etc. There is so much uncertainty on the job site that any adjustment in work may result in a reorganization of informal group members. It could be seen that the particularity of the workers’ work further highlights the characteristics of informal groups with a loose structure and no obvious organizational structure. It should be emphasized that interest groups among construction workers are especially unsteady, and they form and dissolve instantly. “When the wall we contracted was finished, our group disbanded automatically,” was pointed out by Worker III-5. “We will disband when the project department solves our problems,” was illustrated by Worker V-3. Furthermore, conflicts of interest or contradictions between members can also lead to some changes in the members of informal groups. One typical and widespread example cited by Worker V-5 was unequal or unreasonable distributions of wages. Almost all the interviewees agreed with this situation.

4.2.3. A Strong Sense of Group

Members have a strong sense of group regardless of the types of informal groups described in

Section 4.1. Most participants indicated that members are willing to help each other when needed whether at work or in life. Worker III-4 emphasized that whoever can do the work will do it. Next, cooking, washing dishes, and sweeping the floor are chores that help in daily life. When members of informal groups encounter problems, other members will be very anxious and will try to find solutions together. One example given by Manager V-2 was that, “As soon as one of the workers suffers a minor injury at work, the group members all stop working, either going to the hospital or to the boss.” Another example was that some workers cannot count, so in a wage settlement, his relatives, friends, or fellows will help to calculate if the amount is right, something illustrated by Manager I-1. Worker IV-2 also raised the point that as long as there are problems at the construction site, the relatives and friends who come together are anxious. Worker IV-3 added that, “We are a collective, so I am responsible for all of the members.” When members are punished or their interests are violated, they tend to cling together to help speak and find reasons to fight for their peers. Manager II-1 said that if the problem is slightly serious, they will organize to make trouble within the company. To sum up, the group consciousness of the five types of groups is distinctly stronger compared to official teams.

4.2.4. Conformity

In the context of Chinese culture, conformity has always been especially serious in the minds of Chinese people. The low cultural quality of construction workers leads to a more obvious herd mentality. Manager III-1 sighed, saying that construction workers have a severe copycat attitude, and many people do not have their own ideas. They see what acquaintances do and how they do it. Responses such as, “When confronted with disagreement, we usually adopt the solution of minority subordination to the majority (internally)” were expressed by the workers interviewed. Manager V-2 also indicated that workers usually keep in line with their workmates in terms of instructions or orders from their superiors. Whether they comply depends on whether most people do it or not. Interestingly, some of the workers do not want to do certain tasks, but they do them if they see other coworkers do them, as Manager IV-1 demonstrated. In conclusion, construction workers have a strong sense of the code of brotherhood: many of them are “uncouth fellows”, so there is a rendering power in informal groups that cannot be underestimated.

4.2.5. Poor Identifiability

Predictably, IGCWs are hard to identify. The main reasons are as follows. First, they involve the social and emotional needs of workers, while managers do not consciously pay attention to the emotional facets of workers. One response was given as follows by Worker IV-1: “The leaders don’t understand which workmates we usually get together with: they just focus on us doing a good job.” Secondly, current construction workers are basically labor subcontractors. The workers belong to the labor company where they work. This means the managers of project departments have less direct control over the workers. As was revealed by Manager II-1, when they encounter problems or have instructions to convey to workers, they will first find the person in charge of the labor company or the job foreman. Manager I-1 also stated that he has more contact with the owners of labor companies and safety officers and less contact with workers. More importantly, construction sites are large and workers are constantly on the move, making it difficult for managers to keep track of workers. In brief, the vague boundaries of informal groups cause them to have unrecognizable features.

4.2.6. Distance Proximity

According to the interview data, forming IGCWs is characterized by distance proximity. The formation of informal groups is influenced by geographic distance and the length of contact time. Labor is usually subcontracted to several construction teams. Accordingly, the work is divided into different sections, and workers brought by each foreman work and live together. There is basically no intersection between each contractor team, especially between those who build roads and tunnels. For example, Manager III-3 indicated that the New Shui Cao Railway (constructed by his company) reaches a length of 40 km. Manager III-1 also indicated that the members of informal groups are almost like a construction team, and they have more contact with each other. Therefore, there are all kinds of informal groups within every construction team. Manager II-2 reported that informal groups are often found in a dormitory because workers are close. Meanwhile, some participants emphasized that workers in the same occupation are more likely to form informal groups because they work in the same area. This enables them to work at the same pace, which creates an advantage in terms of conditions for the emergence of informal groups. However, it was noted that proximity has a greater impact on the formation of the latter three types of informal groups and a smaller impact on the former two types.

4.2.7. Fast Information Transmission

Undoubtedly, informal communication spreads faster than formal communication in most cases. Whether this is work-related information or what has happened to a workmate, information can quickly propagate among members of informal groups. Moreover, informal communication has more avenues than formal communication does, such as face-to-face communication and making a phone call. Worker II-1 also suggested that he has a “WeChat group” with other workers. An example illustrated by Manager III-1 was that when a worker injured his finger while working, he immediately called his relatives. This response implied that the first thing that comes to mind when a construction worker encounters trouble is his family members, relatives, friends, or fellow townsmen rather than his supervisors. The closer the relationship is, the more he considers it first. Furthermore, numerous interviewees indicated that if an informal group is formed at the site and does not work in one place afterwards, they will still introduce work to one another. The existence of informal groups not only promotes the dissemination of information onsite, but also has a time delay, which is probably one of the reasons why workers are happy to make friends.

4.3. Causes of IGCWs

The root cause of informal groups is due to the sociality of human beings, and the construction industry is no exception. People are generally gregarious, with less emphasis on individuality. Individuals tend to join certain informal groups to obtain a psychological sense of belonging and security. As an old Chinese saying goes, birds of a feather flock together. Worker III-4 said, “I need to make good workmates to eliminate loneliness.” Manager III-2 also expressed that only a handful of introverted and unspoken workers play alone, and most of them come and go together in a small group. Given the characteristics of the construction industry, four subcategories of causes of informal groups were extracted through the axial coding of grounded theory.

Table 7 lists the four main reasons and some informants’ narrations. These subcategories are illustrated in detail below.

Cause 1: According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, human needs are multilayered and multifaceted. Enterprises can only meet the needs of workers at the second level, that is, job security. The psychological needs and emotional needs of workers at the third level are often difficult to satisfy, and they include hobbies, friendships, and private conversations. Since workers are highly mobile and there exists a “traveler mentality”, they do not feel like they belong in their companies. Consequently, they can only form their own informal groups to meet their emotional needs.

Cause 2: As everyone knows, the construction industry has been known for its tough conditions and heavy workload. Workers will go wherever the construction site is, leaving them adrift far from home. When going to a strange place, a person will inevitably be afraid of being deceived and bullied. Therefore, workers will go to construction sites as much as possible with their relatives, friends, and fellow villagers. In addition, on the one hand, the work of the construction industry is complicated and has many variable factors. It is desirable that workers can have their own small groups to coordinate with each other and solve problems together. On the other hand, the work is so intense every day that workers need to relax after work, chatting and drinking with good workmates and complaining about the hard work of the day. In short, if workers have their own informal groups, they can commute to work together and help each other when needed so as to avoid loneliness when working outside.

Cause 3: In China, the construction industry absorbs a large amount of the labor force due to the low threshold for jobs and various types of work. These workers come from different parts of the country, whether they have been engaged in the construction industry before or not, and regardless of age, they can find corresponding jobs. For instance, there will be skilled old masters on the site, such as masonry plasterers, carpenters, and welders, and there will be newcomers who can do nothing. Hence, there is an obvious clubbing phenomenon, i.e., workers with similar backgrounds and common topics will naturally form informal groups: some exchange work, some go out drinking, and some play cards together.

Cause 4: At a construction site, the workers’ scope of activities is small and there are few outside temptations and choices. What they face most is work and workmates. Although workers are mobile and do not stay long at a construction site, living and eating together create opportunities for them to fully understand each other. These objective conditions prompt them to get acquainted with chatty workers and form informal groups with them.

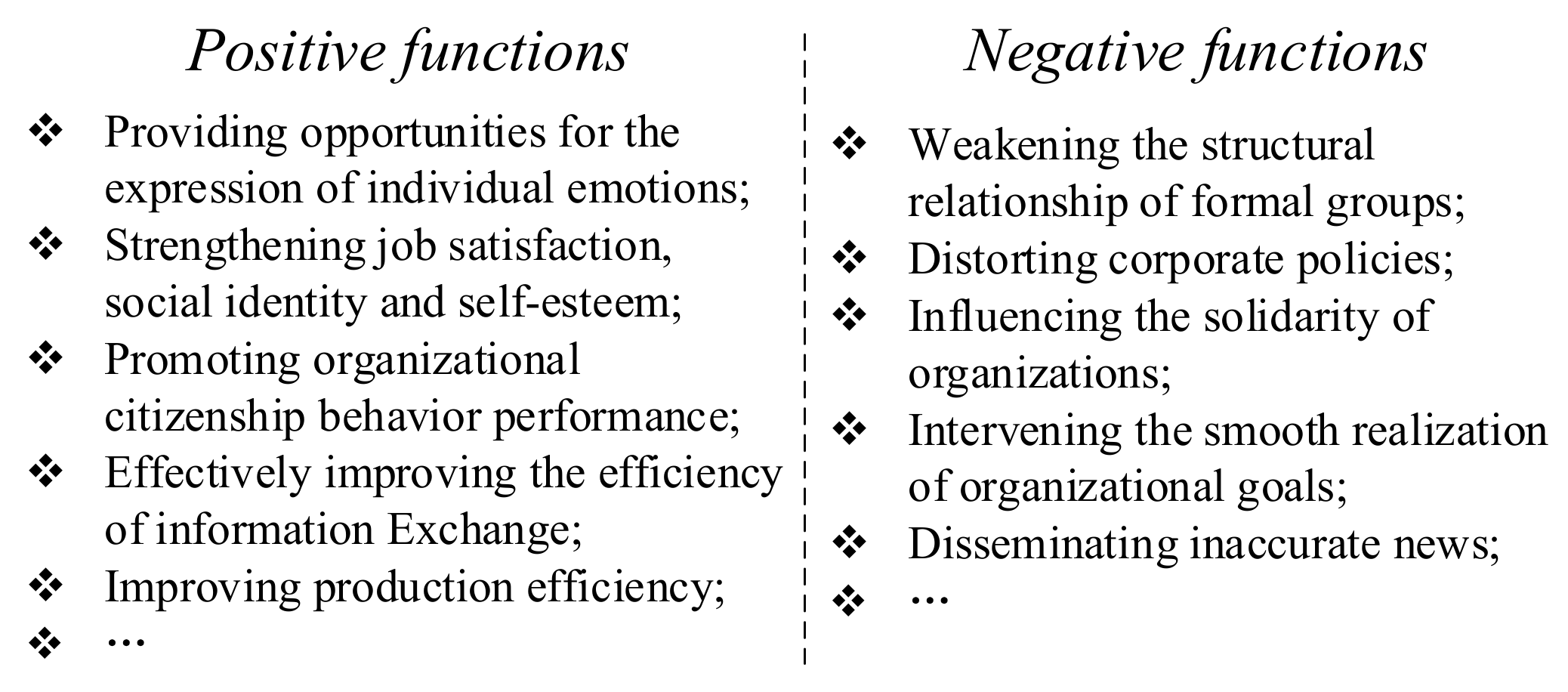

4.4. Functions of IGCWs

In line with the grounded theory method, the interview information was analyzed repeatedly. Ultimately, three levels of incidence that included six positive effects and the corresponding negative effects on companies or workers were identified from high to low. In general, IGCWs have a great positive effect on both enterprises and workers themselves. However, in some cases, these positive effects can spill over into negative ones. The encoded results are shown in

Figure 6. All subcategories in the diagram are described as follows. In addition, the functions of “petty leaders” within informal groups of workers are also expounded upon.

The first level: In this high-risk industry, most workers are far from their homes and relatives, which causes certain mental stress. Informal groups provide a channel for workers to release their feelings, such as irritability and depression. In these groups, workers are given a certain status and identity, which meets the social needs of workers and becomes the spiritual pillar of workers working outside. For example, all of the interviewees responded that forming informal groups with coworkers can make them feel dependent. When they encounter difficulties in work or in life and feel upset, the first people they think about are the members in their informal groups, as was stated by the majority of the interviewees. Manager I-1 also reported that chatting with members of informal groups is a major way for workers to relieve stress, relax, and reduce loneliness. Unfortunately, it is the presence of these informal groups onsite that allows workers to quickly form an interest group that can cause trouble. However, this only happens when workers’ interests are infringed upon, such as when wages are not paid on time.

In addition, since there are many variables in the construction industry, the existence of informal groups can solve plenty of the specific problems that are encountered onsite. First, workers and their relatives, friends, and fellow townsmen come to the construction sites in groups, which can quickly meet the needs of project construction. Manager III-1 and Worker IV-3, for example, cited that “informal groups are good for project completion and can help in obtaining workers”. Next, informal groups have high execution, high efficiency, and fast progress due to their strong cohesion. Almost all of the managers indicated that these two points are the greatest benefits of informal groups. Third, when sites need to meet an urgent task, the informal group formed can rapidly organize to solve the problem and save the construction period. The informal groups based on interests were introduced in

Section 4.1.5. This is a win–win situation for workers and project departments. Nevertheless, it is precisely because they exist as a group that when they are not satisfied, they will strike en masse. This has a huge impact on the progress of projects and is a potential hidden danger for enterprises, as was mentioned by Manager V-2.

The second level: The presence of workers in informal groups reduces the burden on managers. Manager IV-1 emphasized that scattered workers are difficult to manage, which increases the difficulty of virtual management. Meanwhile, informal groups can make up for managers’ lack of work. An obvious example revealed by the participants was that “when working with well-connected coworkers, their moods are pleasant, the working atmosphere is harmonious, and working efficiency will improve accordingly”. Manager II-2 supplemented that it is excellent for enterprises to form informal groups because there is not much contradiction within them and problems can be solved internally. Worker I-1 also added that “when my work style is different from that of other workers, members will advise me on how to be efficient”. Moreover, this does not have a negative impact on the implementation of the project. However, this may weaken the power of managers to some extent. In other words, workers listen more to the “petty leaders” of their informal groups than to managers when opinions diverge.

In addition, informal groups have a strong appeal to their members. Workers comply with the opinions of members of informal groups and tend to act consistently with them as much as possible. A simple example was cited by Manager III-3: “Some workers do not like to wear safety helmets, but if members advise him to wear one, he will choose to wear one.” Another example was cited by Manager III-1: “Some workers do not operate according to standards in order to be quick or because they have formed bad habits. Good workmates persuade them to follow normal operations, and the workers will try to correct their bad habits.” Unfortunately, some bad habits, such as ignoring quality problems of engineering or wasting materials for the sake of ease, are also easy to imitate, and one person’s negative emotions can easily affect other members, thus reducing the work enthusiasm of the whole group. Hence, the role of informal groups in restraining members’ behavior is a double-edged sword.

The third level: As was stated in

Section 4.2.7, the existence of informal groups absolutely promotes the dissemination of information within enterprises. For instance, the vast majority of workers said they would discuss their work problems with close colleagues in private. However, it is exactly because of the extensiveness and permeability of informal communication that some information will be distorted in the process of dissemination, which will eventually damage the interests of enterprises. Manager V-2 illustrated a practical example: if workers heard that the design of Party A had been changed and that they had no work to do, they would immediately contact other relatives and friends and go to another construction site. This would seriously affect the construction schedule. Other managers also pointed out that sometimes misinformation can cause quality defects.

In addition, the mobility of workers makes them have little sense of belonging to the enterprise, but the presence of informal groups on the site can alleviate this situation to some extent. Some workers stated that it is precisely the presence of these informal groups that makes him feel like he belongs here slightly. Informal groups have strong cohesion because of effective internal communication and emotional cultivation. Unfortunately, this is not conducive to solidarity between informal groups. In severe cases, this may lead to the evil practice of cliques and gangs. Manager III-1, for instance, cited that at their construction sites, workers from Chongqing, Sichuan Province, looked down upon local workers, thinking they were poor at their job.

To sum up, informal groups will influence the construction period, cost, quality, and safety of projects (especially safety and the construction period) through influencing workers from many aspects, such as construction behavior, construction efficiency, and information dissemination channels. Therefore, managers should consciously consider the role of informal groups to facilitate organizational goals.

The functions of “petty leaders” in terms of workers: As was described in

Section 4.2.1, there are naturally formed core leaders in informal groups, and we call them “petty leaders”. Through coding, we found that “petty leaders” can influence workers in many ways. The concrete impacts and the informants’ narrations are displayed in

Table 8.