The analysis of the results will be structured as follows: first the opinions of the social enterprises, both at the European and Spanish level, are showed. The second group of answers correspond to the public employees and, finally, a comparison is performed.

4.1. Social Enterprises

4.1.1. European Social Enterprises

A total of 28 complete answers (representing 0,88% of the total number of entities under the umbrella of ENSIE), from which five corresponded to Spanish entities, and therefore have been included in the national group, were received thanks to the partnership with ENSIE. Geographically, nine countries and 15 regions were covered, with Austria being the country with more respondents.

The first set of questions focused on the legal framework and the perceived collaboration with other agents regarding public procurement. As

Table 2 shows, the entities are on average satisfied with the influence they had on the approval of the current legislation and clearly pointed out that public servants show insufficient knowledge of legislation in public procurement.

Collaboration with the public administration is valued higher than collaboration with the commercial enterprises (the term “commercial” is used to distinguish the ordinary enterprises from the social ones). This is logical considering that social businesses work with the public sector through other ways of funding such as subventions or special programs that aim to tackle employment and inequality problems, while they compete with regular businesses in the open market.

Moreover, social entities have, in general, a good impression of their professionalization, meaning that from their point of view they are ready for a more relevant role in public procurement.

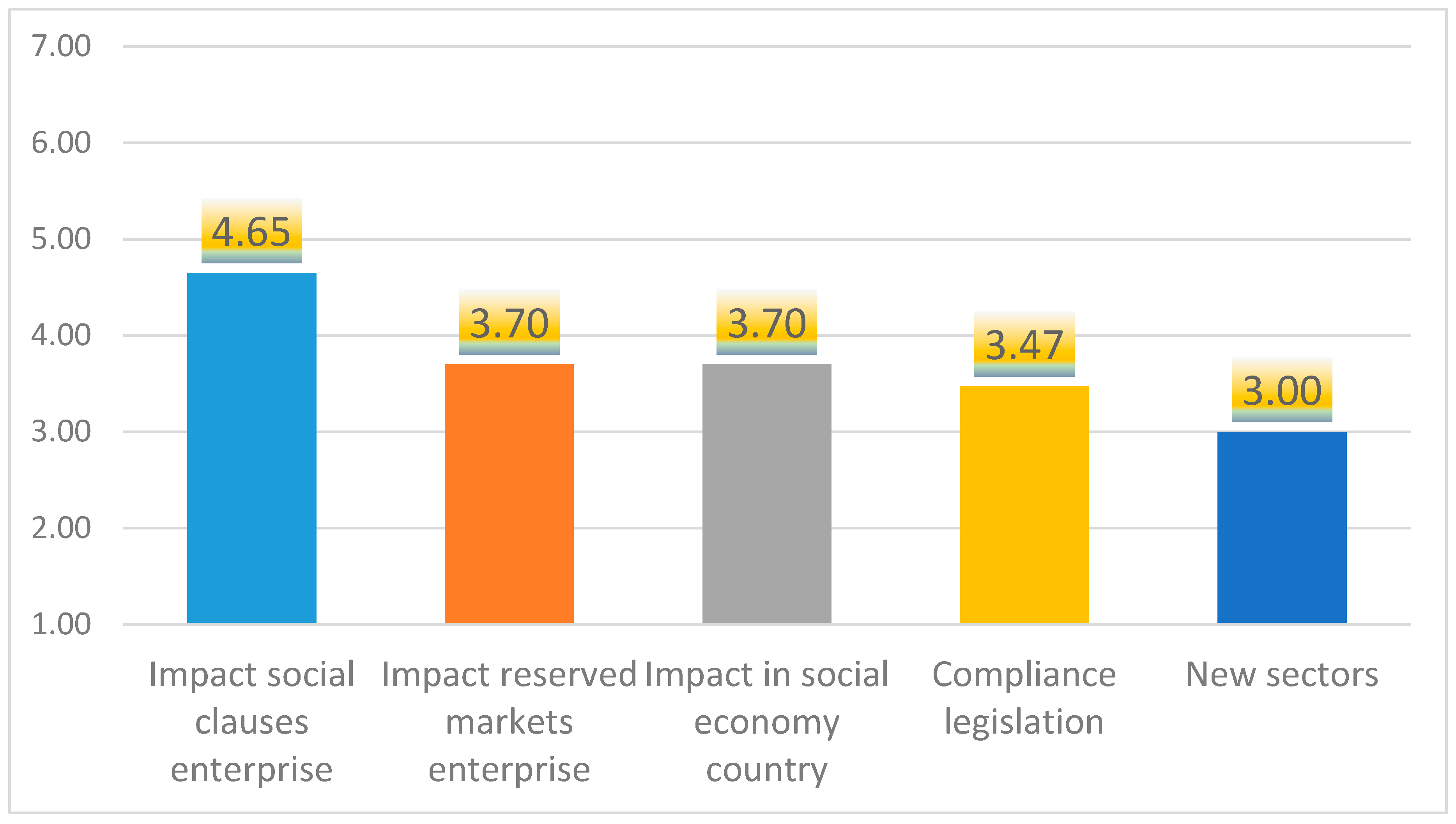

The second set of questions referred to the potential impact of incorporating social and environmental criteria in public procurement procedures. The entities were asked about their perceptions of the impact of social clauses and reserved markets on their own company, the impact of more sustainable procurement in the social economy of their country, their vision of the compliance with the existing legislation and, finally, their opinion on the potential development of new sectors thanks to the introduction of new considerations.

Figure 1 shows the average for each of the considered factors and indicates that, for the European social businesses, the social clauses have more impact at an individual level than on the whole of the social economy and that this impact is more concentrated on the existing activities of the entities, rather than the development of new sectors.

Meanwhile, the reserved markets are perceived to have a lower potential impact than the social clauses, which can be derived from the fact that, in the majority of national legislation, reserved markets have been kept as an option and not as an obligation, unlike in the case of Spain. It is also remarkable that the low degree of legislation compliance is perceived as an obstacle to a bigger impact from the social point of view.

To add qualitative information regarding the development of sustainable procurement, the final section of the survey included two questions about the perceived opportunities and obstacles related to the introduction of social and environmental clauses. The respondents were asked to give a maximum of two opportunities and two obstacles.

The opportunities for the development of the sustainable procurement can be classified into the following three categories: employment, social entities themselves, and the impact on society in general. With regards to employment, social procurement favors the inclusion of people far from the job market, which is consistent with the existing doctrine in the area.

The social entities perceive an opportunity for more visibility and relevance linked with more access to public procurement. The realization of services, work, and supplies could impact positively on the image of professionalization of these type of entities, which are normally perceived as being connected only with caritative and voluntary activities. From the economic point of view, lower dependence on public funding such as subventions (and the uncertainty associated to them) is another of the positive effects that were pointed out, allowing the social entities to have a more structured plan for their business activities.

Another effect mentioned was the increase of collaboration, both with commercial enterprises which could see the social entities as equal players to collaborate with, and with the public sector. A bigger participation in public procurement would benefit the potential lobby activities of the social economy and would also reinforce its role as a regular provider of services and supplies.

Regarding society in general, and in line with what has been expressed in the European legislation, sustainable public procurement is seen as a vehicle to support poverty reduction and inequalities, and to develop more environmentally sustainable practices.

In terms of the obstacles, public administration, public employees, capitalist enterprises, and the social entities received most of the criticism. Their lack of political willingness for the necessary changes for the model, which translates into insufficient application of the law and corruption, was generally mentioned. In addition, the lack of knowledge by public servants and the complexity of the processes are clear examples of the factors hindering a wider application of the legislation.

It is precisely the legislation that was another focus of complaints, since it is considered to be too complex and subjective, thus provoking legal insecurity. The attitude of commercial enterprises against the development of new ways of procurement was expressed by several of the respondents. Lastly, it is important to note the existence of self-criticism among the social entities, which pointed out the lack of lobbying, the risk of devaluation or their social tasks if they had to compete in pricing, and the lack of legalization and market niches for the collectives at risk of exclusion.

4.1.2. Spanish Social Enterprises

A total of 195 personalized questionnaires were sent to social enterprises to gather their opinion on matters similar to those asked by the European ones, with the addition of a new section that focused on the ease or difficulty of implementing the different social and environmental criteria that the Spanish Law 9/2017 offers. Sixty-five complete answers (i.e., a 33.33% response rate) from 13 of the 17 autonomous regions in Spain were received, with Catalonia and the Canary Islands representing the largest share.

The results obtained in the second section, legal framework and governance of public procurement, showed similarities with those enterprises studied at the European level. As shown in

Table 3, the main concern of the social businesses was the low level of knowledge of public servants about the legislation (with a minimum value of 2.42 points on a seven-point scale).

The perceived low level of influence on shaping legislation might be interpreted as a weakness by the social entities and it indicates that they perceive a lack of power as lobbyists. As with the questionnaires at the European level, the most valued collaboration was the relationship between the social economy entities and the public administration, and the relationship with the commercial enterprises was another disturbing point. In addition, the perception of professionalization was lower than at the European level, which could hinder the possibilities of being up to the challenge of having greater participation in public procurement.

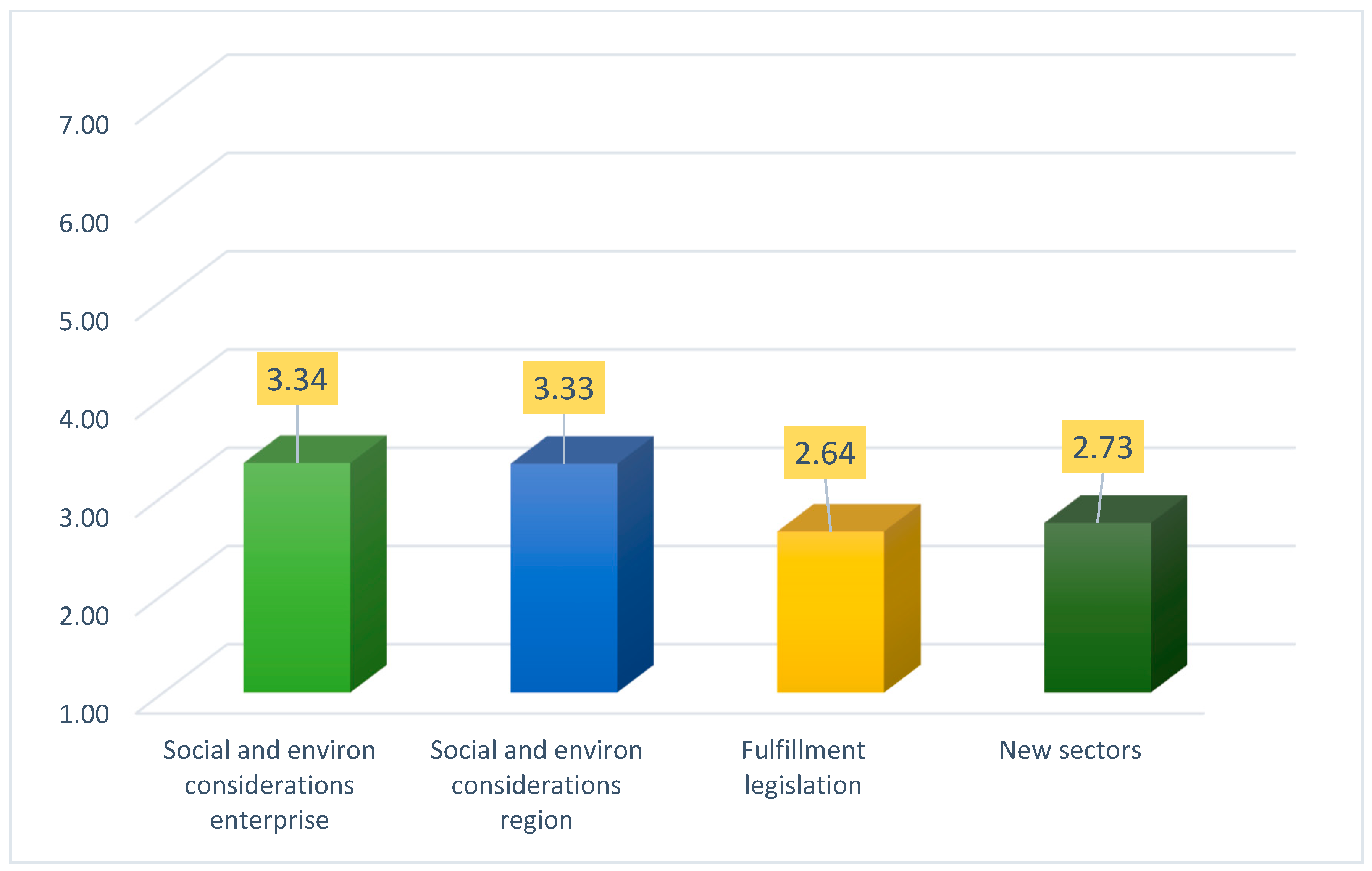

With respect to the potential impacts of social considerations, the Spanish enterprises are less optimistic than the European enterprises. As shown in

Figure 2, there is a lower level for the impact of social and environmental considerations, both in the enterprises and in the region in general, and, especially, a very poor assessment of the compliance with the recently approved legislation concerning sustainable procurement, which is valued as 2.64 points on a seven-point scale.

Therefore, social entities are identified as a greater obstacle than the existence of proper legislation contributing to sustainable procurement. Hence, political willingness could be one of the impediments for the development of such legislation and is further analyzed in depth later in this paper.

Responsible criteria are seen more as a vehicle for consolidation of the existing activities than as a tool to develop new ones. This follows the logic of Law 9/2017, which includes a list of restricted sectors for the reserved procurement based on the traditional activities the social entities carry out in its Annex VI.

A new section of questions was introduced to establish a base of comparison with the opinions of public servants. The aim of the questions was to evaluate the degree of difficulty for introducing a series of social and environmental criteria. To delimit the criteria, the list with the possibilities included in article 145 of Law 9/2017 was used, adding the possibility of reserved procurement.

The results in

Table 4 express a certain homogeneity on the perceived difficulty for implementing the criteria, since the majority of them are between 3.5 and 3.9. In general, it can be asserted that, for social entities, the introduction of such considerations should not be difficult. The results for the variation coefficients were below 50% for most of the variables, and therefore rendered the average obtained a representative value.

In this study, the following three factors were below the average: equal opportunity between women and men, subcontracting with social entities, and reserved procurements. The explanation for the first one might lay in the existence of a consolidated legislation in this field, in Spain, (especially Law 3/2007 for effective equality between women and men) which supports the introduction of these considerations. Moreover, the perception of high professionalization by the social entities reinforces the possibility of establishing subcontracting with them as an award criterion (or even as a condition for the execution of the contract). Additionally, the numerous successful cases for reserved contracts in Spain [

5] could encourage their use.

Among the considered criteria, those perceived to be more difficult to implement were related to employment, both in general and in regard to people at risk of exclusion. This could be due to the tendency of using price criterion as the decisive factor in contracts and the controversy that labor issues as social criteria have had in the tribunals. Finally, environmental criteria were considered less difficult to implement than social criteria (on average), reinforcing the idea that there is less litigation involved.

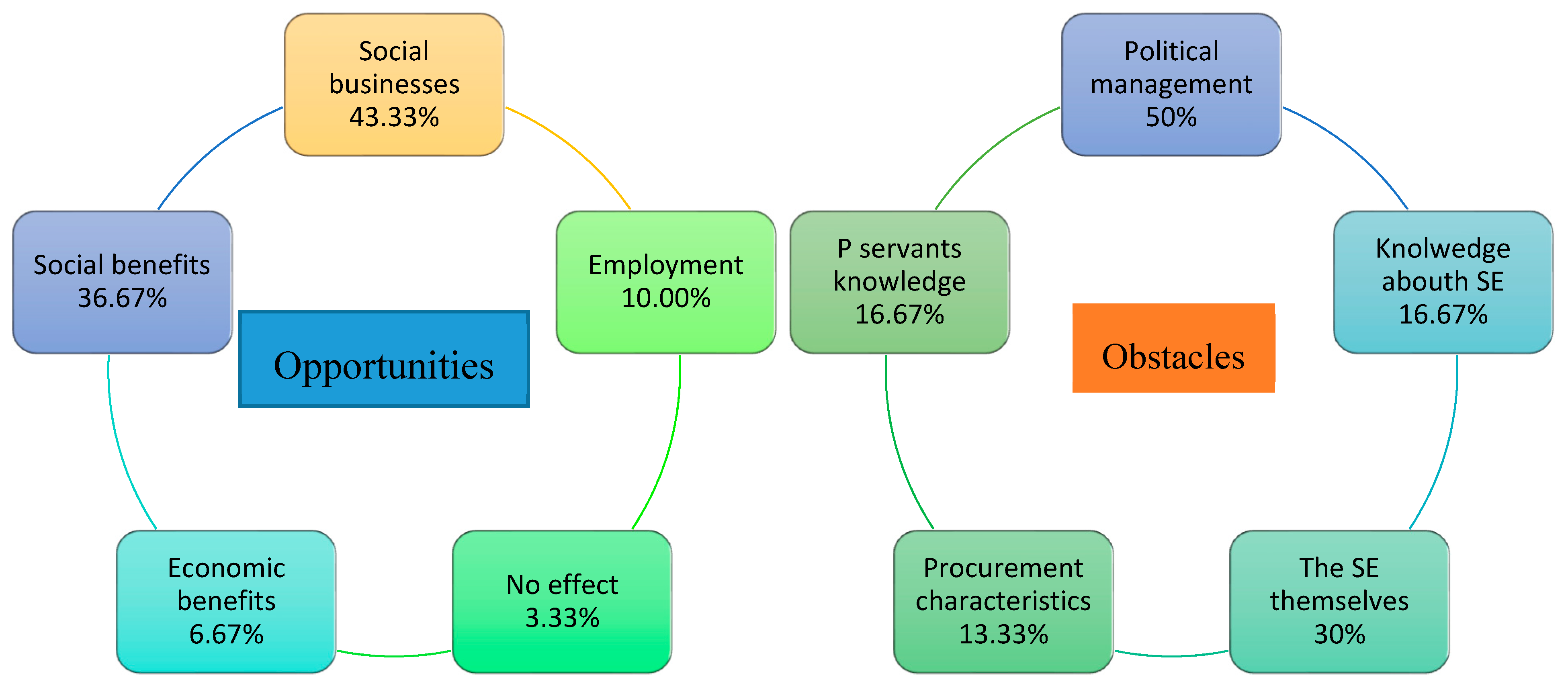

As in the case of the European entities, the questionnaire also included two questions asking about the opportunities and obstacles of a more sustainable public procurement. In comparison to the supranational level, there was a greater variety of answers, both positive and negative, that can be classified into five categories, as shown in

Figure 3.

Benefits for social businesses were the most frequently mentioned. A more positive image, more visibility, bigger financial security, and presence in the market leading to an increase in competitiveness and employment were highlighted as the potential positive effects. In the social benefits category, more stable employment for people at risk of exclusion and growth in opportunities to join the regulated labor market were highlighted.

Regarding employment, two positive effects were expected, creation of job positions and more professionalization of the people at risk of exclusion and already working. This, in turn, shows an advantage in economic terms both in the increase of the economic return of these type of entities, and in a fairer distribution of public expenditure.

No opportunities linked with commercial entities were mentioned, as was the case for social and environmental consideration leading to more sustainable activities, which indicates a lack of trust in commercial entities from social businesses, and the perception of their attitude as an obstacle for the implementation of the legislation.

In terms of obstacles, public management is the greatest threat to the development of sustainable procurement. Most of the critics focus on lack of political willingness, low interest in change, and a lack of sensibility, knowledge, and awareness. In addition, issues previously mentioned at the European level, such as the incorrect application of the law or the complexity of the law itself, are added to new concerns such as prioritization of price, lack of interdepartmental coordination, and lack of knowledge of the social economy, in general.

Again, self-criticism arose among the social entities, when people pointed at themselves as possible obstacles for social procurement due to their lack of motivation and eagerness to participate more actively in public competition.

4.1.3. Social Entities and Personal Interviews

As indicated above, 20 personal interviews were carried out with managers of social entities which were aimed at getting deeper into more qualitative aspects of sustainable public procurement. The aspects addressed through the phone or in person included: preference between social and environmental consideration and reserved procurements, obstacles for sustainable procurement, readiness of social enterprises and public administration, attitude of the commercial businesses, and the forecasted evolution of the sustainable procurement. Managers from six different Spanish regions agreed to personal interviews, with most of them located in Catalonia and the Basque Country.

4.1.4. Preference between Social Clauses and Reserved Procurements

There was a similar number of respondents that choose the first and the second option. The argument in favor of reserved procurements identified the greater advantage that they give to social entities, because they secure that only a certain type of organization can participate.

To support social and environmental considerations, the respondents focused on employment, arguing that it is more beneficial for people far from the job market to be contracted directly by commercial enterprises. In addition, social clauses are seen as a way to push professionalization on social entities and achieve the necessary balance between economic survival and social development.

One group of managers pointed out the complementarity of both tools, with both being necessary to achieve “a protocol of sustainable procurement that combines a percentage of reserved procurements with social clauses”. Moreover, the two options allow, in the opinion of one of the respondents “a bigger visibility of our job and the people we work with”.

4.1.5. Obstacles to Sustainable Public Procurement

Although there was a specific question about this topic in the surveys, to obtain a more detailed description this section was also included in the personal interviews. The answers confirmed the aforementioned concerns from the social side, and therefore lack of knowledge among civil servants, as well as lack of political willingness were mentioned in most of the answers.

In the first group, the non-division in lots (that now is compulsory according to article 99 of Law 9/2017) was highlighted, which “may be caused by the lack of knowledge that the administration shows” and diminishes the “possibilities of working together for the social enterprises”.

Commercial enterprises also appear as an obstacle, due to the oligopolistic practices and the offers with extremely low prices. According to one of the respondents, the businesses “do not agree with the social considerations, although a positive evolution can be seen, linked with the development of the corporate social responsibility”.

4.1.6. Readiness of the Public Administration for Sustainable Procurement

The lack of training was pointed out by the majority of the interviewees as one cause for the slow development of sustainable procurement in Spain. In addition, the “prevalence of the economic criteria in the procurement” was another stumbling block, however, positive cases were also mentioned and “some administrations are making a big effort for the change” which is visible through the editing of different guides and recommendations.

4.1.7. Readiness of Social Businesses

The degree of preparation of social entities to face more participation in procurement was also discussed. In this regard, there was almost unanimity considering that they have “knowledge on the subject” and are mostly “competitive with the added value of being a social enterprise”. Nevertheless, the amount of the contracts can be an obstacle that many entities could not save, due to the fact that they are local and normally small enterprises, which could not reach the threshold for economic and technical solvency.

This raises the question of division in lots as one of the possible points of conflict between public administration and social entities, since it might imply more administrative tasks from the public side and the need for adjustments to coordinate diverse enterprises.

4.1.8. Commercial Enterprises

The influence of commercial enterprises over sustainable public procurement does not have a common answer. Half of the interviewees mentioned them as a potential threat, since they oppose any change in procurement and see the sustainable considerations as a breach to free concurrency because they might favor certain businesses.

This does not preclude the existence of channels of collaboration between social and commercial businesses, and some of the respondents mentioned the creation of working groups and protocols for sustainable development. The establishment of temporal unions as enterprises for participation in some contracts shows the possibilities of professionalization of the sector due to more collaboration. In addition, as the sustainable considerations increase their presence, the commercial enterprises are also aware of their importance and seek a way to introduce them in their offerings.

4.1.9. The Evolution of Sustainable Public Procurement

The last question addressed the impact and future of sustainable procurement. Most of the interviewees were optimistic in that sustainable public procurement could contribute by supporting expansion of the working possibilities for people at risk of exclusion and by strengthening the work of social entities and the development of local, nonprofit entities, avoiding speculation and corruption.

Sustainable procurement is expected to continue to grow in the future, with more administration assuming their central role as a social agent and changing their view of procurement from finalist to strategic. Reserved procurements are the preferred tool to do so, since they secure activities currently going on, but the implementation of sustainable procurement still lacks the training of public servants and more stable channels of communication among the different agents.

4.2. The Opinion of the Public Sector

4.2.1. Analysis of the Surveys

The same structure as the one used to collect information on the social sector was used to gather the opinion of the public employees. The questionnaire included similar questions to favor comparison and was divided into the following four sections: training and knowledge, implementation of sustainable procurement, obstacles and opportunities, and the relation with the social businesses. A total of 152 complete answers were received from seven different regions in Spain, almost equally distributed between administrative levels. The local level, with 40.30% of the answers, was the most represented.

As pointed out previously, the level of knowledge about the implementation a more sustainable public procurement is a key factor for success. In this context, the opinions expressed reflect quite a pessimistic panorama. As

Table 5 shows, the level of knowledge about the legislation among the people who oversee its implementation is relatively low, and so is the knowledge and perceived relationship with the social entities.

Therefore, the following two weaknesses are identified: the lack of knowledge about the new legislation, and the lack of knowledge about social businesses as potential partners. The first is directly related to the lack of training received by public servants. Almost 73% of the respondents expressed that they had not received training courses at the time of answering the survey, although practically all of them responded positively to the possibility of attending specialized courses on the issue.

The second part of the questionnaire was grounded on the opinion about the implementation of the sustainable considerations. A question was added about the difficulty of introducing sustainable criteria in each phase of the procurement. The results show similar levels of assessment between the preparation, the awarding, and the execution phase, ranging from 3.83 to 3.93.

The responses about concrete criteria to be introduced (the same posed for the social businesses) show that the public employees perceive more difficulties in introducing social and environmental criteria than the social enterprises (

Table 6).

The answers are more homogeneous in this case, with variation coefficients that do not pass the 50% threshold for any of the variables. The more remarkable differences between the two groups reside in the criteria related to fair trade and especially regarding the implementation of reserved procurement, which is valued as almost 1.5 times more difficult by the public side. This can be linked to the lack of knowledge about the entities that could benefit from the reserve and it is one of the factors that can harm their participation in procurement.

Although public servants express that they perceive the implementation of the criteria to be more complex in general, the environmental criteria and those related to equality between women and men continue to be the ones considered to be the easiest to implement.

The third segment of the survey inquired about the administrative levels and the productive sectors where the sustainable practices were more likely to be developed. There is no clear conclusion about the first part, because, as

Figure 4 shows, the municipal and provincial levels collect more of the answers in both categories and in many of the cases where the first was considered the easiest level, the second was considered the most difficult, and vice versa.

More unanimity can be found about the sectors in which the sustainable procurement could be more easily implemented. More than half of the respondents considered the tertiary sector as the most ideal contracts. Within the tertiary sector, services that are intensive in work force and have lower requirements for training were mentioned, such as social activities, cleaning, health, gardening, and waste management.

Contrary to this, works and supplies were the activities that respondents expressed as being more difficult to introduce social and environmental criteria. In addition, services that require high specialization such as architecture, consultancy, and those with intense use of technology are also in this group.

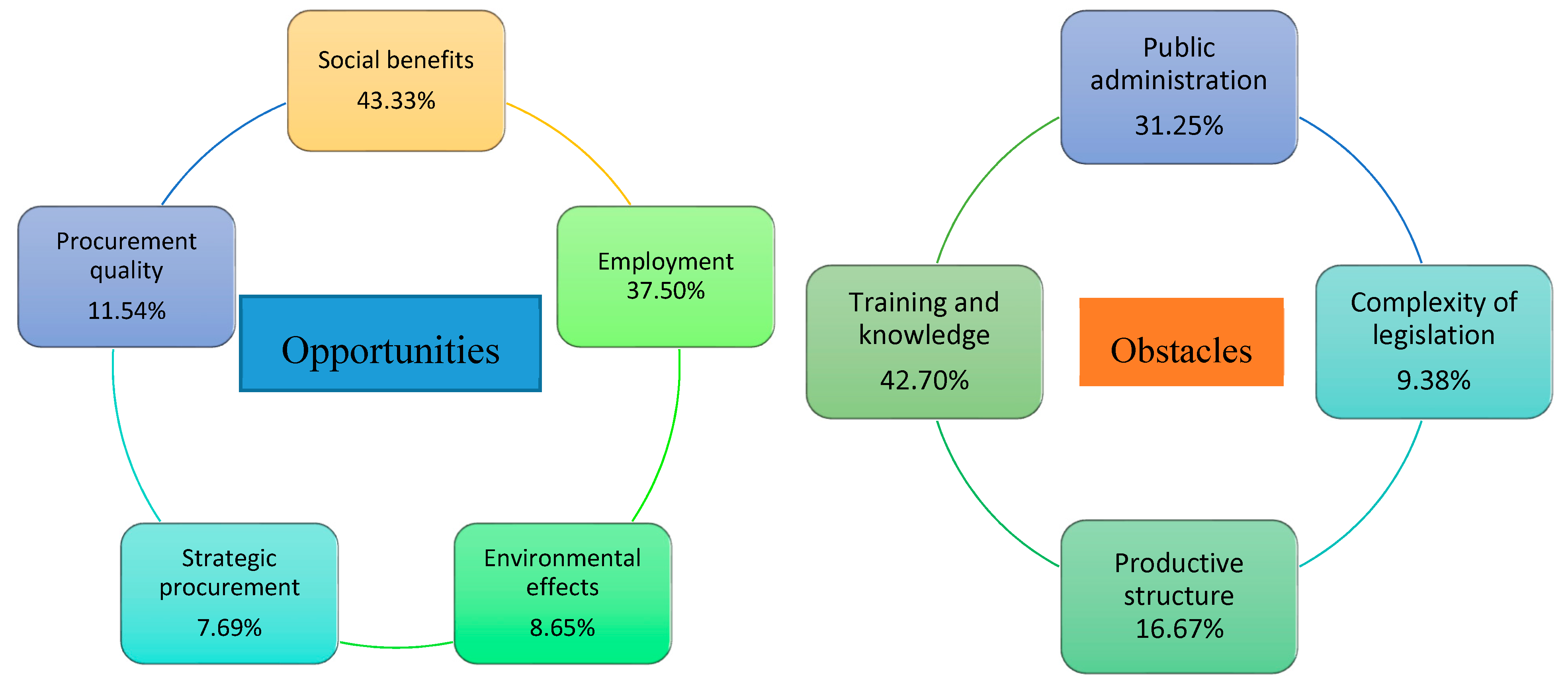

The last group of questions entailed the perceived opportunities and obstacles to implementing a more sustainable procurement. Moreover, respondents were asked their opinion about the attitude of commercial enterprises towards social and environmental criteria. In this case, as

Figure 5 shows, the responses can be classified in different groups.

The majority of answers highlighted the potential of sustainable public procurement in areas such as social justice, equality, and better opportunities for people at risk of exclusion. Employment was especially mentioned as well, since sustainable procurement can help to improve labor conditions, wage equality, and labor dignity. Sustainable procurement is seen as a way to increase the quality of public expenditures, balancing social, environmental, and economic aspects and helping change the traditional mentality that links the cheapest with the best. The strategic vision of public procurement can promote a change of culture where social corporate responsibility (private and public) would have more importance, leading to a more positive perception of the citizens about public procurement practices.

On the side of the obstacles, training arises again (this time from the point of view of the public sector) as one of the “stoppers” for the introduction of new criteria. The lack of knowledge relates to the fear of change, due to the juridical insecurity, and hinders the development of more sustainable practices. Furthermore, as pointed out by the social enterprises, the lack of willingness of the public administrations is frequently mentioned by the respondents, who complain about the immobilism of the public sector and the miss practicing that can lead to corruption and continuation of clientelism.

Nevertheless, factors outside the public sector are also mentioned. The existing productive structure, with a majority of SMEs, a scarce industrial sector, and many businesses which still give low attention to issues beyond the economic ones, are considered barriers to the change. Finally, the legislation itself is said to be complex and unclear, thus, creating insecurity for their application.

4.2.2. Personal Interviews

To complete the information obtained from the surveys a group of people from the public sector was interviewed personally or by phone. The selected people came from different administrative levels, i.e., local, regional, and national and were nationally recognized experts on the topic. In contrast to the social enterprises, there was no structured script for the interview. The characteristics of the interviewees and their role in public procurement are presented in

Table 1.

The questions posed to the experts in the public sector addressed factors related to their personal experience in the development of more sustainable public procurement. The interviewees were asked to express their opinions about the main obstacles to the implementation of the new social and environmental considerations and the key factors that could hinder or foster it.

Javier Tena considered that public procurement should be more similar to the private one and expressed that the public sector “does not know how to negotiate”. Social considerations can help, but there are still many gaps to bridge. For example, the question about the selection and control of the right collective bargain agreement remains unsolved and generates insecurity for public servants.

For Mr. Tena, commercial enterprises “will adapt” to the new obligations if they want to compete in public procurement. In addition, the introduction of social clauses is supportive, but he also recommended performing a previous study on the potential effects they might have and the correct contract to use to introduce them. It is possible that the action would be more efficient if they were implemented, for instance, using the framework of the Social European Fund.

Gustavo Zaragoza highlighted the importance of creating working groups that involve the private and public sectors for the successful implementation of sustainable procurement. In his opinion “social clauses are part of the corporate social responsibility of the public administration in their role to impulse social change with more active social policies”.

Municipalities are in a better position to implement sustainable practices, although there is still a long process ahead. Commercial enterprises “do not have normally a positive attitude and some appeals have been made against social criteria, but in general they are starting to accept them”.

For Luis Bentue, free concurrency has to be present when developing sustainable criteria. Environmental criteria, for instance, can be formulated in terms of “carbon footprint”, favoring proximity alternatives. He recommended establishing a plan for the third sector to improve its visibility and “push the public operators to reserve contracts”.

Lastly, Maria Jesús Serrano was satisfied with Law 9/2017, which “goes further than the directives in social and transparency issues”. The law could allow social and environmental considerations to have a larger role without eliminating the price criteria. The increased requirements on transparency are not an obstacle to good management.

4.3. Comparing Public and Private Sector

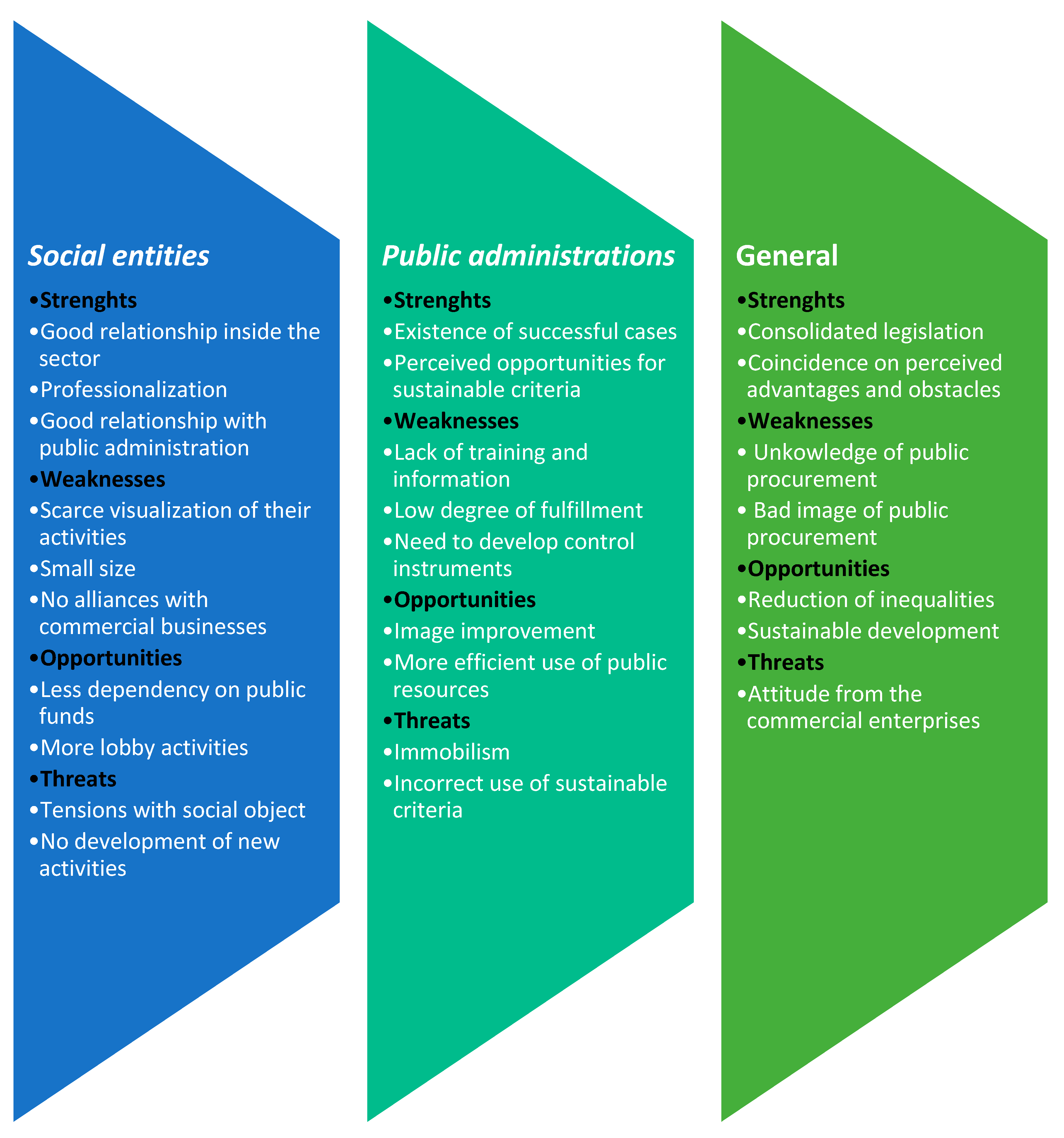

The surveys included common questions to expand the comparisons between the two groups into the following three aspects: knowledge on legislation, the difficulty of implementing certain criteria, and the opportunities and obstacles for sustainable procurement.

The low perception of public servants’ knowledge about existing legislation is common to both groups and shows the need for more training and information in the public sector. Additionally, social entities are generally unknown to the public servants, indicating the need for actions from the social sector that raise awareness and establish collaboration channels.

As for the analysis of the implementation of different criteria in the procurement process,

Table 7 shows that for all the criteria, the public sector perceives them as more difficulty than the social businesses, with an average of 13.65%.

The greatest differences can be found for the criteria directly related to social businesses, the subcontracting with them, and the reserved markets. This is especially worrying, taking into account that the implementation of these considerations is linked directly to the lack of knowledge about these organizations by the public sector, who are still not aware of their activities.

Employment, on the contrary, conceals more similar answers, both, in general, and for certain collectives, as does the equality between women and men. The vast legislation in place can be one of the positive supports for this situation. The environmental criteria are perceived to be easier to implement than the social criteria and are in both cases below the average valuation.

Social benefits are mentioned as one of the main opportunities that sustainable procurement could bring. Similarly, employment is also another positive effect when introducing social criteria, and both groups see an opportunity for their own development and reputation that could be derived by putting quality over price.

Both groups agreed that status quo public administration was an obstacle to the advancement of more sustainable practices. Training and knowledge are cited as two of the necessities to be covered and legislation is mentioned, although for two different reasons. From the point of view of public servants, it is complex and lacks clarity, while the social businesses complain about the inadequate application and that the contracts do not adapt to their characteristics.

The productive structure is also highlighted as an obstacle by both groups. For the public administration, there is an insufficient number of enterprises ready for procurement. This is recognized from the social entities when they point out the need for more professionalization and readiness.

Regarding the results derived from the personal interviews, although the structures were different, both groups are in agreement on their optimism about the future development of sustainable procurement, pointing out the necessity for more professionalization in the public sector.