Family Business Succession in Different National Contexts: A Fuzzy-Set QCA Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Individual Characteristics

2.2. Motivation for Succession

2.3. Family Business Characteristics

2.4. Succession Plan

3. Methods

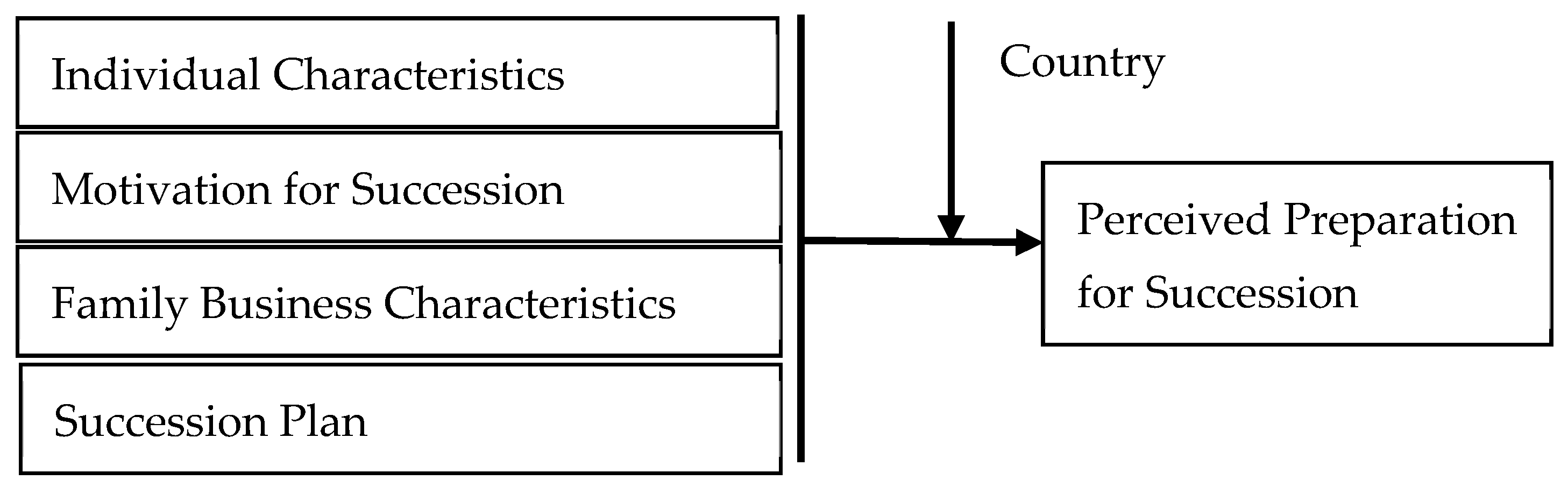

3.1. Research Model and Propositions

3.2. Methodology, Conditions, and Outcome

3.3. Sample

4. Results and Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Contributions

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Magazine, T. The Economic Impact of Family Business. Tharawat Mag. 2014, 22. Available online: https://www.tharawat-magazine.com/magazine/issue-22-economic-impact-family-business/#gs.fh55hl (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- Adjei, E.K.; Eriksson, R.H.; Lindgren, U. Social proximity and firm performance: The importance of family member ties in workplaces. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2016, 3, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.; Fattoum, S.; Thébauld, S. A suitable boy? Gendered roles and hierarchies in family business succession. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2018, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilding, M.; Gregory, S.; Cosson, B. Motives and outcomes in family business succession planning. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Suárez, M.K.; Martín-Santana, J.D. Successor’s commitment and succession success: Dimensions and antecedents in the small Spanish family firm. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 2736–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, F.; Bernhard, F.; Nacht, J.; McCann, G. The relevance of a whole-person learning approach to family business education: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2015, 14, 322–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork, D. Family Business, Risky Business; AMACON: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Nelton, S. Love and in Business: How Entrepreneurial Couples Are Changing the Rules of Business and Marriage; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Salganicoff, M. Women in family business: Challenges and opportunities. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1990, 3, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Williams, R.W.; Nel, D. Factors influencing family business succession. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 1996, 2, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, E.; Boshoff, C.; Maas, G. The influence of successor-related factors on the succession process in small and medium-sized family businesses. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2005, 18, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barach, J.A.; Gantisky, J.B. Successful succession in family business. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1995, 8, 131–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.S.; Schenkel, M.T.; Kim, J. Examining the impact of inherited succession identity on family firm performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2014, 52, 246–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, J.J., III; Justis, R.T. The development of successors from followers to leaders in small family firms: An exploratory study. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2009, 22, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagne, M.; Sharma, P.; De Massis, A. The study of organizational behavior in family business. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatak, I.R.; Roessl, D. Relational competence based knowledge transfer within intrafamily succession: An experimental study. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2015, 28, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Irving, P.G. Four bases of family business successor commitment: Antecedents and consequences. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.-N.; Luo, X.R. Leadership succession and firm performance in an emerging economy: Successor origin, relational embeddedness, and legitimacy. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, J.; Palmberg, J.; Wiberg, D. Inherited corporate control and returns on investment. Small. Bus. Econ. 2013, 41, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, P.; Marchisio, G.; Astrachan, J. Strategic planning in family business: A powerful developmental tool for the next generation. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2008, 21, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNoble, A.; Ehrlich, S.; Singh, G. Toward the development of a family business self-efficacy scale: A resource-based perspective. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2007, 20, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyromalis, V.D.; Vozikis, G.S. Mapping the successful succession process in family firms: Evidence from Greece. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2009, 5, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, I.; Lubinski, C. Crossroads of family business research and firm demography—A critical assessment of family business survival rates. J. Fam. Bus. Strateg. 2011, 2, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, C. Framed by Gender: How Gender Inequality Persists in the Modern World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN-13 9780199755776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, S.J.; Ridgeway, C.L. Expectation States Theory. In Handbook of Social Psychology; Delamater, J., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, J.; Conner, T.L.; Fisek, M.H. Expectation States Theory: A Theoretical Research Program; Winthrop: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, J.; Fisek, M.H.; Norman, R.; Zelditch, M. Status Characteristics and Social Interaction; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, J.; Zelditch, M. Status, Power, and Legitimacy: Strategies and Theories; Transaction: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Barach, J.A.; Gantisky, J.; Carson, J.A.; Doochin, B.A. Entry of the next generation: Strategic challenge for family business. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1988, 26, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Brockhaus, R.H. Family business succession: Suggestions for future research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2004, 17, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Suárez, K.; De Saá-Pérez, P.; García-Almeida, D. The succession process from a resource and knowledge-based view of the family firm. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2001, 14, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampa, D.; Watkins, M. The successor’s dilemma. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1999, 77, 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, K. Is succession such a sweet dream? Fam. Bus. Rev. 1999, 10, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J.L. Keeping the Family Business Healthy: How to Plan for Continuing Growth, Profitability and Family Leadership; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H. Predictors of satisfaction with the succession process in family firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Zacharakis, A. Structuring family business succession: An analysis of the future leader’s decision making. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2000, 24, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audet, J.; Berger-Douce, S.; St-Jean, E. Perceptual barriers preventing small business owners from using public support services: Evidence from Canada. Int. J. Entrep. 2007, 11, 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, H.E. Networking among women entrepreneurs. In Women-Owned Businesses; Hagan, O., Rivchum, C., Sexton, D.L., Eds.; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 13–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cuba, R.; Decenzo, D.; Anish, A. Management practices of successful female business owners. Am. J. Small Bus. 1983, 2, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harveston, P.D.; Davis, P.S.; Lyden, J.A. Succession planning in family business: The impact of owner gender. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1997, 10, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, C. Daughters in Family-Owned Businesses: An Applied Systems Perspective; Fielding Institute: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 1989; Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, C. Preparing the new CEO: Managing the father-daughter succession process in family business. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1990, 3, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, C.F.; Dean, M.A. An examination of the challenges daughters face in family business succession. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2005, 18, 321–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.; Constantinidis, C. Sex and gender in family business succession research: A review and forward agenda from a social construction perspective. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2017, 30, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottardo, P.; Moisello, A.M. Family firms, risk-taking and financial distress. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2017, 15, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansberg, I.S. The succession conspiracy. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1988, 1, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.; Lambrechts, F. Investigating the actual career decisions of the next generation: The impact of family business involvement. J. Fam. Bus. Strateg. 2015, 6, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doescher, W.F. How to shake the family tree. D B Rep. 1993, July/August, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fenn, D. Are your kids good enough to run your business? INC 1994, August, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt, J. Fathers and sons. INC 1992, May, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, R.L. Second-generation entrepreneurs: Passing the baton in the privately-held company. Manag. Decis. 1991, 29, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberly, J.R.; Evanisko, M.J. Organizational innovation: The influence of individual, organizational and contextual factors on hospital adoption of technological and administrative innovations. Acad. Manag. J. 1981, 24, 689–713. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, D.K.; Guthrie, J.P. Executive succession: Organizational antecedents of CEO characteristics. Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, S.; Simons, R.; Boyd, B.; Rafferty, A. Promoting family: A contingency model of family business succession. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2008, 21, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H.; Sharma, P. Important attributes of successors in family businesses: An exploratory study. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1998, 11, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Rao, S. Successor attributes in Indian and Canadian family firms: A comparative study. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2000, 13, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cespedes, F.V.; Galford, R.M. Succession and Failure. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Chrisman, J.J.; Pablo, A.L.; Chua, J.H. Determinants of initial satisfaction with the succession process in family firms: A conceptual model. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2001, 25, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, W.C. Succession in family business: A review of the research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1994, 7, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, E. Succession in family businesses: Exploring the effects of demographic factors on offspring intentions to join and take over the business. J. Small. Bus. Manag. 1999, 37, 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, J.H.; Chrisman, J.J.; Sharma, P. Succession and nonsuccession concerns of family firms and agency relationship with nonfamily managers. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2003, 16, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molly, V.; Laveren, E.; Deloof, M. Family business succession and its impact on financial structure and performance. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2010, 23, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucculelli, M.; Micucci, G. Family succession and firm performance: Evidence from Italian family firms. J. Corp. Financ. 2008, 14, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrachan, J.H.; Kolenko, T.A. A neglected factor explaining family business success: Human resource practices. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1994, 7, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumentritt, T. The relationship between boards and planning in family businesses. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2006, 19, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, J.E., III; Leon-Guerrero, A.Y.; Haley, J.D., Jr. Strategic goals and practices of innovative family businesses. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2001, 39, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H.; Steier, L. Sources and consequences of distinctive familiness: An introduction. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella-Carrubi, M.D.; González-Cruz, T.F. Context as a provider of key resources for succession: A case study of sustainable family firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Steier, L.; Le Breton-Miller, I. Lost in time: Intergenerational succession, change, and failure in family business. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helin, J.; Jabri, M. Family business succession in dialogue: The case of differing backgrounds and views. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arregle, J.-L.; Duran, P.; Hitt, M.A.; van Essen, M. Why is family firms’ internationalization unique? A meta-analysis. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 801–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, G. Cross-country differences in intergenerational earnings mobility. J. Econ. Perspect. 2002, 16, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturelli, A.; Caputo, F.; Leopizzi, R.; Pizzi, S. The state of art of corporate social disclosure before the introduction of non-financial reporting directive: A cross country analysis. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 15, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Jiang, Y. Institutions behind family ownership and control in large firms. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.Q.; Wageman, C. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roig-Tierno, N.; Huarng, K.-H.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Qualitative comparative analysis: Crisp and fuzzy sets in business and management. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1261–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Richter, C.; Brem, A.; Cheng, C.-F.; Chang, M.-L. Strategies for reward-based crowdfunding campaigns. J. Innov. Knowl. 2016, 1, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenes, E.R.; Ciravegna, L.; Woodside, A.G. Constructing useful models of firms’ heterogeneities in implemented strategies and performance outcomes. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 62, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, D.; Zollo, M.; Hansen, M.T. Faking it or muddling through? Understanding decoupling in response to stakeholder pressures. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1429–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliadis, S.; Vassiliadis, A. The Greek family businesses and the succession problem. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 9, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howorth, C.; Zahra Assaraf, A. Family business succession in Portugal: An examination of case studies in the furniture industry. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2001, 14, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Marcelo, J.L.; Miralles-Quirós, M.D.M.; Lisboa, I. The impact of family control on firm performance: Evidence from Portugal and Spain. J. Fam. Bus. Strateg. 2014, 5, 56–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrachan, J.H.; Klein, S.B.; Smyrnios, K.X. The F-PEC Scale of Family Influence: A proposal for solving the Family Business Definition Problem. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2002, 55, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Minichilli, A.; Corbetta, G. Is Family Leadership always beneficial? Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, J.; Amann, B.; Jaussaud, J.; Kurashina, T. Impact of Family Control on the performance and Financial Characteristics of Family versus Nonfamily Businesses in Japan: A Matched-Pair Investigation. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2008, 21, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghee, W.Y.; Ibrahim, M.D.; Abdul-Halim, H. Family business succession planning: Unleashing the key factors of business performance. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 20, 103–126. [Google Scholar]

| Aggregate | Conditions | Description | Original Scale | References | Calibration | Descriptive Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Characteristics | Gender | Gender of the family business successor | Male or female | [9,37,38,39,40,41,42] | Female = 1 Male = 0 | Females account for 37.5% of the sample |

| Age | Age of the family business successor | 18–25; 26–30; 31–35; 35+ | [46,47] | >35 (older) = 1 18–35 (younger) = 0 | Older family business successors account for 62.5% of the sample | |

| Education | Maximum level of formal or informal instruction reached by the family business successor | High school; university level; post-graduate; and vocational education training | [10,48,49,50,51,52,53] | University level or post-graduate (high) = 1 High school or vocational education (low) = 0 | University level or post-graduate account for 84.4% of the sample | |

| Motivation for Succession | Motivation | Perceived motivation of successors for the “announced” succession | (1) I had no alternative; (2) My family expected me to inherit the business; (3) It seemed to be the natural course of events; (4) It seemed a good career opportunity; or (5) I thought it would be an opportunity to put innovative ideas to practice. Answers (1), (2), and (3) were classified as not proactive, and answers (4) and (5) were classified as proactive toward succession | [4,5,15,16,55,56] | Non-proactive (low) = 0 Proactive (high) = 1 | Proactive motivation accounts for 50.8% of the sample |

| Family Business Characteristics | Maturity | Maturity of the family business based on the number of family generations so far | 2nd generation; 3rd generation; older than 3rd generation | [13,31] | 2nd generation = 0 3rd generation or more (high) = 1 | 3rd generation or more account for 29.7% of the sample |

| Size | Number of employees of the family business | 1–9; 10–49; 50–99; 100–249; 250+ | [11,14,60] | 1–9 (micro) = 0 10–249 (SMEs) = 1 | SMEs account for 58.6% of the sample | |

| Succession Plan | Plan | Does a plan exist for succession in the family business? | Yes or no | [4,20,35,66,67] | No = 0 Yes = 1 | 17.2% of the family businesses in the sample have a succession plan |

| Context | Country | Country of origin and where the family business operates | Portugal or Greece | [5,81,82,83] | N/A | 47 Portuguese and 87 Greek family businesses included in the sample |

| Successors’ Perceived Preparation for Succession | Perceived Preparation for Succession | (1) I lack the skills and knowledge to manage the family business; (2) I am not yet ready and well prepared to run the business; (3) I do not have the required knowledge about the family business; (4) I am not able to take over all the functions that the previous leader held; (5) The process of succession is very demanding in terms of family relations and the sentimental burden is high; (6) Family and business matters are complex and intertwined; and (7) We are facing family related issues that I cannot manage and discuss with others | Average of the 7 items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85): low/v. low importance = 4; moderate importance = 3; high importance = 2; v. high importance = 1. Missing values were imputed as the average of the available variables | [15,56] | Average = 2.20 Percentile 10 = 1.24 Percentile 90 = 3.20 |

| Aggregate | Conditions | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Characteristics of Successors | Gender | ○ | ● | ● | |

| Age | ● | ● | ○ | ● | |

| Education | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | |

| Motivation for Succession | Motivation | ● | ● | ○ | ● |

| Family Business Characteristics | Maturity | ○ | ● | ○ | ● |

| Size | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Succession Plan | Plan | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Consistency | 0.95 | 0.75 | 0.92 | 0.92 | |

| Raw Coverage | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.06 | |

| Unique Coverage | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.06 | |

| Overall Solution Consistency | 0.91 | ||||

| Overall Solution Coverage | 0.34 | ||||

| Aggregate | Conditions | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | S11 | S12 | S13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual characteristics of successors | Gender | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ||

| Age | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ● | |

| Education | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ||||

| Motivation for succession | Motivation | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | |

| Family business characteristics | Maturity | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | |

| Size | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | |

| Succession plan | Plan | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | |

| Consistency | 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.82 | |

| Raw coverage | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | |

| Unique coverage | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Overall solution consistency | 0.85 | |||||||||||||

| Overall solution coverage | 0.48 | |||||||||||||

| Aggregate | Conditions | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual characteristics of successors | Gender | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Age | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ||

| Education | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Motivation for succession | Motivation | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | |

| Family business characteristics | Maturity | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| Size | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | |

| Succession plan | Plan | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Consistency | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.89 | |

| Raw coverage | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.11 | |

| Unique coverage | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.11 | |

| Overall solution consistency | 0.83 | |||||||

| Overall solution coverage | 0.66 | |||||||

| Aggregate | Conditions | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual characteristics of successors | Gender | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | |

| Age | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | |

| Education | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| Motivation | Motivation | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ||

| Family business characteristics | Maturity | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Size | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||

| Succession plan | Plan | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Consistency | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.98 | 0.88 | |

| Raw coverage | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Unique coverage | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Overall solution consistency | 0.89 | ||||||||||

| Overall solution coverage | 0.40 | ||||||||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Porfírio, J.A.; Carrilho, T.; Hassid, J.; Rodrigues, R. Family Business Succession in Different National Contexts: A Fuzzy-Set QCA Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6309. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226309

Porfírio JA, Carrilho T, Hassid J, Rodrigues R. Family Business Succession in Different National Contexts: A Fuzzy-Set QCA Approach. Sustainability. 2019; 11(22):6309. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226309

Chicago/Turabian StylePorfírio, José António, Tiago Carrilho, Joseph Hassid, and Ricardo Rodrigues. 2019. "Family Business Succession in Different National Contexts: A Fuzzy-Set QCA Approach" Sustainability 11, no. 22: 6309. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226309

APA StylePorfírio, J. A., Carrilho, T., Hassid, J., & Rodrigues, R. (2019). Family Business Succession in Different National Contexts: A Fuzzy-Set QCA Approach. Sustainability, 11(22), 6309. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226309