Teachers’ Transgressive Pedagogical Practices in Context: Ecology, Politics, and Social Change

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Teachers, Education, and the Environment

1.2. An Approach to the Chilean Neoliberal Context in the Framework of Education and the Environment

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Theory: Convergence between Pragmatism and Phenomenology: Knowledge, Meanings, and Action

2.2. Method

2.3. Analysis and Interpretation

3. Results

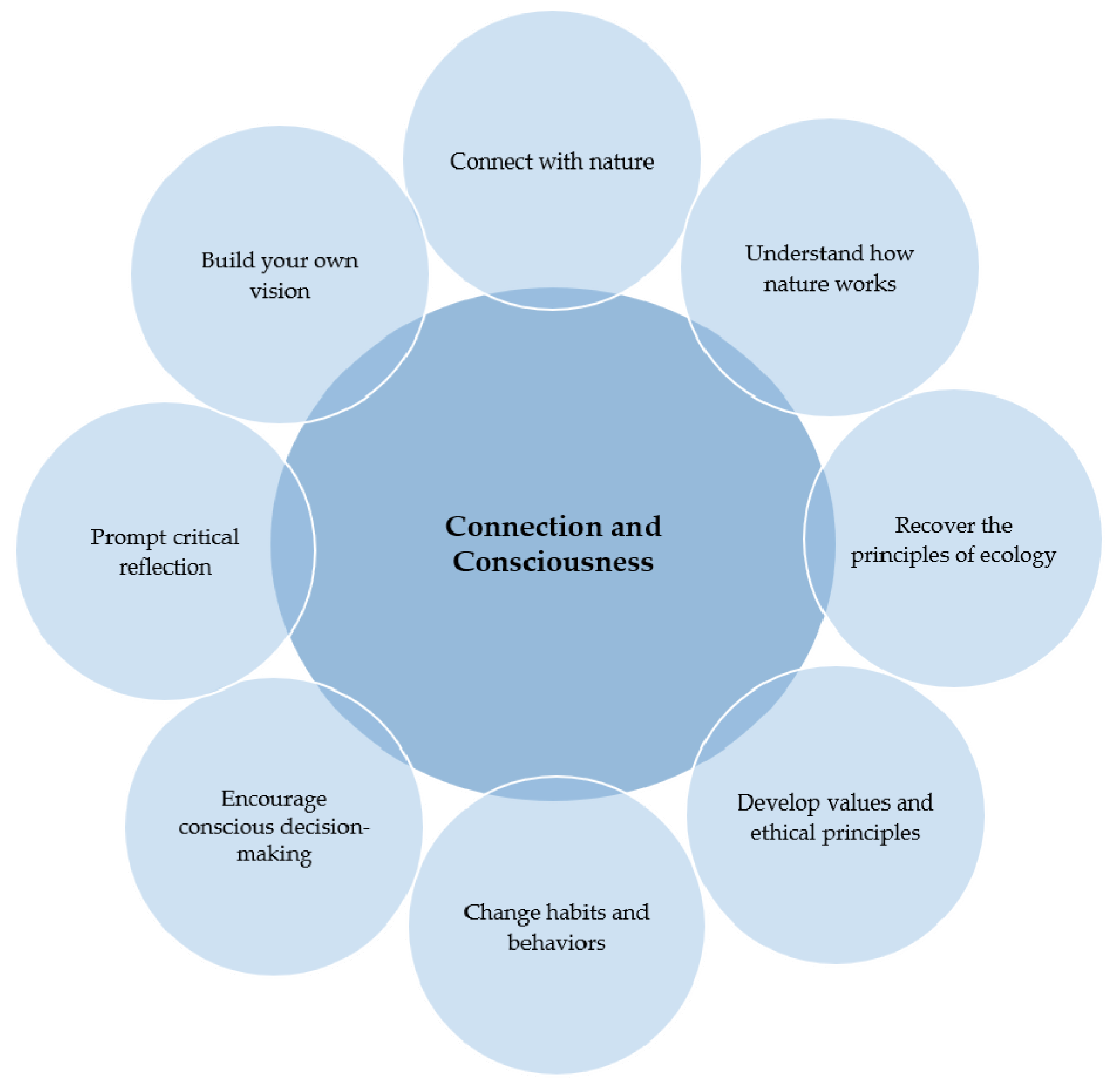

3.1. ‘Connection and Consciousness’

“...appreciation of nature, a deep connection with nature, being passionate about it, becoming conscious that what you are seeing is not external, but also part of you. I believe that is a quite spiritual component.”

Interviewer: “What do you think it is important for students to learn about the environment?”

Diana: “On the environment, one can develop a lot of skills with the student that will be useful for developing your life as an integral being (...) a powerful formation in the sphere of values, in the sphere of conservation. (...). That student is going to behave in a friendly way towards the environment and is going to want to live in a much fairer society with more social justice.”

(...)

Interviewer: “And what actions go ‘beyond’ as you mentioned?”

Diana: “It has to do with reflection; a child, however small, can be taught to reflect critically about the environment, and, on reaching maturity (...) has to have the capacity to think about why the environment is the way it is. What happens? (...) Then the child, or the young person, has to reach a stage where he or she definitively says ‘Hey, there’s a mess on the planet with the mechanisms of production, this capitalist system or whatever you want to call it. (...) It definitely makes inequity increase and precisely the segregated continue to be segregated (...) green areas are not distributed equally across different neighborhoods.’”

“…to break with certain cultural traditions (…) and take a different view that is simple, humble, seeks equity and justice, looks at things in a different way (...) different types of leadership and that finally is a matter of consciousness and then it is more relevant to do what we do.”(Nicanor)

“But let it be nature that makes you reflect and finally empowers you and makes you say ‘look, I can collaborate with this action, I can activate here and connect with others because, ultimately, alone, it would only be activism.’”(Diana).

“When I was at the academy, I was on the level of criticism and did not have the tools or practical methodologies to be able to find what the real change was going to be. For me, everything that has to do with ecology, with these changes of habits, with valuing ancestral traditions (...) I find that, in those moments, they make more sense. They are really educational experiences that can be replicated in schools, in universities.”(Danissa).

“I have to see biogeochemical cycles, how boring! (...) As concepts, they are very dry. So we said, ‘Let’s see the cycles, but from the standpoint of environmental problems (...) together with language’.”(Nicanor)

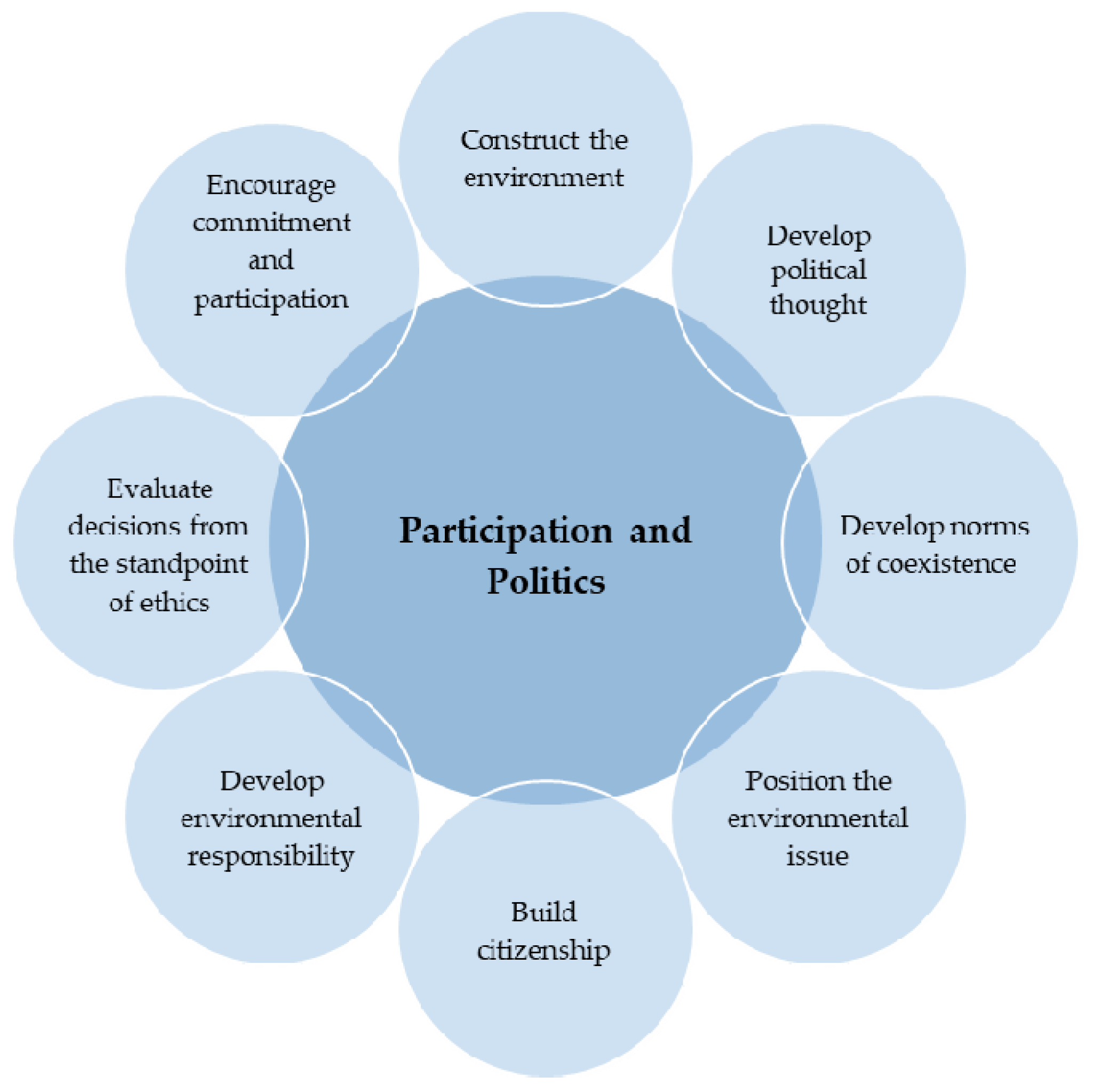

3.2. ‘Participation and Politics’

“Last year, I relied a lot on the proposals of ecology and sustainable development; it’s easy to find material from the Ministry and in the literature. Obviously, the idea was to create consciousness (…) in other words, care for water, electricity (…) and I tell them that these actions should be common sense by now, it’s not as if we need to be saying it all the time. (...) I took that liberty because the school already has an eco-monitors program (…) so I think that instance is already there.”(Luis)

Interviewer: “How do you approach environmental issues?”

Juan: “... from the standpoint of participation and especially opinion, from what an individual can do to evaluate their surroundings and be able to say ‘what do I do to contribute to generating my surroundings?’ (...) I seek to form (...) students committed to a cause, really committed to a cause, regardless of whether that cause is purely environmentalist or may be of another type. (...) I always appeal to the capacity for organization, participation, and information.”

“They would be working with a syllabus that, in the first place, has to do with their interests. Second, they would be making use of a healthy democratic exercise within the school space. Third, it would no longer be exclusively the adult-centric approach of saying, ‘Hey, I demand you learn this and I don’t care what you want to learn; you have to learn this?’”(Juan)

“This space seems strange to the students. (...) In this oasis, I can think and then not, it’s weird for them and for me; I was very accustomed to working with the content of the curriculum (...) test, grades. (...) What I did at the beginning of this year was to leave a unit of topics proposed by them (...) This year, I left it for the end of the year because I realized that, by the end of the process, they were more accustomed and had more confidence to put forward ideas.”(Luis)

“We are going to register with the local Town Hall (…) with the idea of always trying to work with the clear idea of the assembly. I have tried to put a lot of emphasis on what an assembly or horizontality mean. (…) I don’t know what will come of this. I hope that only good things. But I don’t know, I don’t know.”

“We have to think about how caring for nature is related to education, which is very similar to the formal education that other people had before, but not everyone is receiving now.”

"When I took on the vegetable garden workshop, I did not have much experience of planting and I told the girls ‘Here we are going to explore together’.”

4. Discussion

5. Final Comments

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morin, E. Los Siete Saberes Necesarios Para La Educación Del Futuro; Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Condeza-Marmentini, A.; Flores-González, L.M. Configurations and meanings of environmental knowledge: Transitions from the subjective experience of students towards the intersubjective experience of us. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, D. Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sund, P.; Lysgaard, J.G. Reclaim “Education” in Environmental and Sustainability Education Research. Sustainability 2013, 5, 1598–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jickling, B.; Wals, A.E.J. Normative Dimensions of Environmental Education Research Conceptions of Education and Environmental Ethics; AERA: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Le Grange, L. Why We Need a Language of (Environmental) Education. In International Handbook of Research on Environmental Education; Stevenson, R.B., Brody, M., Dillon, J., Wals, A.E.J., Eds.; AERA: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Assambly, G., Ed.; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, D.A. A Critical Theory of Place-Conscious Education. In International Handbook of Research on Environmental Education; Stevenson, R.B., Brody, M., Dillon, J., Wals, A.E.J., Eds.; AERA: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013; pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, D.A. Why Place Matters Environment, Culture, and Education. In Handbook of Research in the Social Foundations of Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 632–640. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, D.A. A critical pedagogy of place: From gridlock to parallax. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, D.A. Foundations of Place: A Multidisciplinary Framework for Place-Conscious Education. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 4, 619–654. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, M. The places of pedagogy: Or, what we can do with culture through intersubjective experiences. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, E.; McKenzie, M.; McCoy, K. Land education: Indigenous, post-colonial, and decolonizing perspective on place and environmental education research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyer, A.; Kelsey, E. Environmental Education in a Cultural Context. In International Handbook of Research on Environmental Education; Stevenson, R.B., Brody, M., Dillon, J., Wals, A.E.J., Eds.; AERA: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Tilbury, D.M.; Mulà, I. A Review of Education for Sustainable Development Policies from a Cultural Diversity and Intercultural Dialogue Perspective: Identifying Opportunities for Future Action; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nurse, K. Culture as the fourth pillar of sustainable development. In Proceedings of the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, London, UK, 16–20 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, N. Thinking Globally in Environmental Education: Implications for Internationalizing Curriculum Inquiry. In International Handbook of Curriculum, Pinar, W.F., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA; London, UK, 2003; pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- González-Gaudiano, E.J.; Lorenzetti, L. Trends, Junctures, and Disjunctures in Latin American Environmental Education Research. In International Handbook of Research on Environmental Education; Stevenson, R.B., Brody, M., Dillon, J., Wals, A.E.J., Eds.; AERA: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013; pp. 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- González-Gaudiano, E.J. Schooling and environment in Latin America in the third millennium. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Wals, A.B.J.; Kronlid, D.; McGarry, D. Transformative, transgressive social learning: Rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 16, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H. Reviewing strategies in/for ESD policy engagement: Agency reclaimed. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 47, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G.J.J. The Beautiful Risk of Education; Paradigm: Boulder, CO, USA; London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G.J.J. Against learning. Reclaiming a language for education in an age of learning. Nord. Pedagog. 2005, 25, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G.J.J. Good Education in an Age of Measurement: Ethics, Politics, Democracy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G.J.J. Good education in an age of measurement: On the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 2009, 21, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P. Teachers’ Thinking in Environmental Education: Consciousenes and Responsability; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Öhman, J. Moral Perspectives in Selective Traditions of Environmental Education—Conditions for environmental moral meaning-making and students’ constitution as democratic citizens. In Learning to Change Our World? Swedish Research on Education & Sustainable Development; Wickenberg, P.E.A., Ed.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2004; pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sund, P.; Wickman, P.O. Teachers’ objects of responsibility: Something to care about in education for sustainable development? Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sund, P.; Wickman, P.O. Socialization content in schools and education for sustainable development—I. A study of teachers’ selective traditions. Environ. Educ. Res. 2011, 17, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikel, J. Making sense of education ‘responsibly’: Findings from a study of student teachers’ understanding(s) of education, sustainable development and Education for Sustainable Development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, R.B. Schooling and environmental education: Contradictions in purpose and practice. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.; Nolan, K. A critical analysis of research in enviromental education. Stud. Sci. Educ. 1999, 34, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S. Teachers’ environmental education as creating cracks and ruptures in school education: A narrative inquiry and an analysis of teacher rhetoric. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castoriadis, C. El Campo de lo social histórico. Estud. Filos. -Hist. -Let. 1986, 4, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G.J.J. Freeing Teaching from Learning: Opening Up Existential Possibilities in Educational Relationships. Stud. Phil. Educ. 2015, 34, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.; Gough, S. Sustainable Development and Learning: Framing the Issues; RoutledgeFalmer: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, R.T. Teachers’ Views about What to do about Sustainable Development. Environ. Educ. Res. 1998, 4, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corney, G.; Reid, A. Student teachers’ learning about subject matter and pedagogy in education for sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, M.; Corney, G.; Childs, A. Teaching Sustainable Development in Primary Schools: An empirical study of issues for teachers. Environ. Educ. Res. 2003, 9, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, C.; Gericke, N.; Hoglund, H.O.; Bergman, E. The barriers encountered by teachers implementing education for sustainable development: Discipline bound differences and teaching traditions. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2012, 30, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, C.; Gericke, N.; Hoglund, H.O.; Bergman, E. Subject- and experience-bound differences in teachers’ conceptual understanding of sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 526–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarnio-Linnanvuori, E. How do teachers perceive environmental responsibility? Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasslöf, H.; Malmberg, C. Critical thinking as room for subjectification in Education for Sustainable Development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Lam, C.-C.; Wong, N.-Y. Developing an Instrument for Identifying Secondary Teachers’ Beliefs About Education for Sustainable Development in China. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 41, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raselimo, M.; Wilmot, D. Geography teachers’ interpretation of a curriculum reform initiative: The case of the Lesotho Environmental Education Support Project (LEESP). S. Afr. J. Educ. 2013, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.; Halse, C.M. Environmental attitudes of pre-service teachers: A conceptual and methodological dilemma in cross-cultural data collection. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2005, 6, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waktola, D.K. Challenges and opportunities in mainstreaming environmental education into the curricula of teachers’ colleges in Ethiopia. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketlhoilwe, M.J. Governmentality in environmental education policy discourses: A qualitative study of teachers in Botswana. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2013, 22, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, H. Negotiating managerialism: Professional recognition and teachers of sustainable development education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gaudiano, E.J. Otra lectura a la historia de la educación ambiental en América Latina y el Caribe. Tópicos En Educ. Ambient. 1999, 1, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Pedreros, A. La educación ambiental en Chile, una tarea aún pendiente. Ambiente Soc. 2014, 17, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squella, M.P. Environmental Education to Environmental Sustainability. Educ. Phil. 2001, 33, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, D.; Fernández, M.B.; Ossa Parra, M.; Berger, A.; Borba, G. The Fourth Way of Leadership and Change in Latin America: Prospects for Chile, Colombia, and Brazil. Pensam. Educ. Rev. De Investig. Educ. Latinoam. 2013, 50, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, A. Mecanismos performativos de la institucionalidad educativa en Chile: Pasos hacia un nuevo sujeto cultural. Obs. Cult. 2013, 15, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- MMA. Bases Generales del Medio Ambiente; Ministerio de Medio Ambiente Chile: Santiago, Chile, 1993.

- Gonzáles-Muñoz, M.C. Principales tendencias y modelos de la Educación Ambiental en el sistema escolar. Rev. Iberoam. De Educ. —Educ. Ambient. Teoría Y Práctica 1996, 11, 13–68. [Google Scholar]

- MMA. Diagnóstico de Compromiso en Sustentabilidad de las Universidades Chilenas; Ministerio de Medio Ambiente Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2017.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phénoménologie de la Perception; Gallimard, É., Ed.; Librairie Gallimard: Paris, France, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F.J. El Fenómeno de la Vida; Dolmen: Santiago, Chile, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G.J.J.; Burbules, N. Pragmatism and Educational Research; Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Experience and Nature. The Later Works of John Dewey; Boydston, J.A., Ed.; Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale, IL, USA; Edwardsville, IL, USA, 1988; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J.; Bentley, A. Knowing and the known. In John Dewey: The Later Works, 1949–1952; Boydston, J.A., Ed.; SIU Press: Carbondale, IL, USA, 1991; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Art as Experience; Perigee Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F.J.; Thompson, E.; Rosh, E. The Embodied Mind. Cognitive Science and Human Experience; MIT: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, Y.; Valois, P. École et Sociétés; Éditions Agence d’Arc: Montreal, QC, Canada, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sandell, K.; Öhman, J.; Östman, L. Education for Sustainable Development: Nature, School and Democracy; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvé, L. Una cartografía de corrientes en Educación Ambiental. In A Pesquisa em Educação Ambiental: Cartografias de uma Identidade Narrativa em Formação; Sato, M., Carvalho, I., Eds.; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvé, L. Exploración de la Diversidad de Conceptos y de Prácticas en la Educación Relativa al Ambiente. Seminario Internacional: La Dimensión Ambiental y la Escuela, Bogotá, Colombia. Available online: http://koha.ideam.gov.co/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=40541&shelfbrowse_itemnumber=39650 (accessed on 26 October 2019).

- Sterling, S. Higher Education, Sustainability, and the role of Systemic Learning. In Higher Education and the Challenge of Sustainability; Corcoran, P.B., Wals, A.E.J., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D. Experiential Learning as the Science of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mouffe, C. The Return of the Political; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mouffe, C. On the Political; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leff, E. La ecología política en América Latina. Un campo en construcción. Polis Rev. Académica Univ. Boliv. 2003, 1, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, E. Pensamiento Ambiental Latinoamericano: Patrimonio de un Saber para la Sustentabilidad. In Proceedings of the VI Congreso Iberoamericano de Educación Ambiental, San Clemente de Tuyú, Argentina, 16–19 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, A. Encountering Development. The Making and Unmaking of the Third World; Priceton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gudynas, E. Desarrollo, extractivismo y postextractivismo. In Proceedings of the Seminario Andino: Transiciones, postextractivismo y alternativas al extractivismo en los países andinos, Lima, Peru, 16–18 May 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gudynas, E. Diez tesis urgentes sobre el nuevo extractivismo. Contextos y demandas bajo el progresismo sudamericano actual. In Extractivismo, Política y Sociedad; Centro Andino de Acción Popular (CAAP) y Centro Latino Americano de Ecología Social (CLAES): Quito, Ecuador, 2009; pp. 187–225. [Google Scholar]

- Alier, J.M. El Ecologismo de los Pobres. Conflictos Ambientales y Lenguajes de Valoración, 3rd ed.; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvé, L. Environmental Education and Sustainable Development: A Further Appraisal. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 1996, 1, 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H.A. Introduction. In La Naturaleza Política de la Educación: Cultura, Poder y Liberación; Paidos: Barcelona, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa Santos, B. Construyendo las Epistemologías del Sur. Antología Escencial; Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvé, L.; Berryman, T. Language and Discourses of Education, Environment and Sustainable Development. In International Handbook of Research on Environmental Education; Stevenson, R.B., Brody, M., Dillon, J., Wals, A.E.J., Eds.; AERA: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

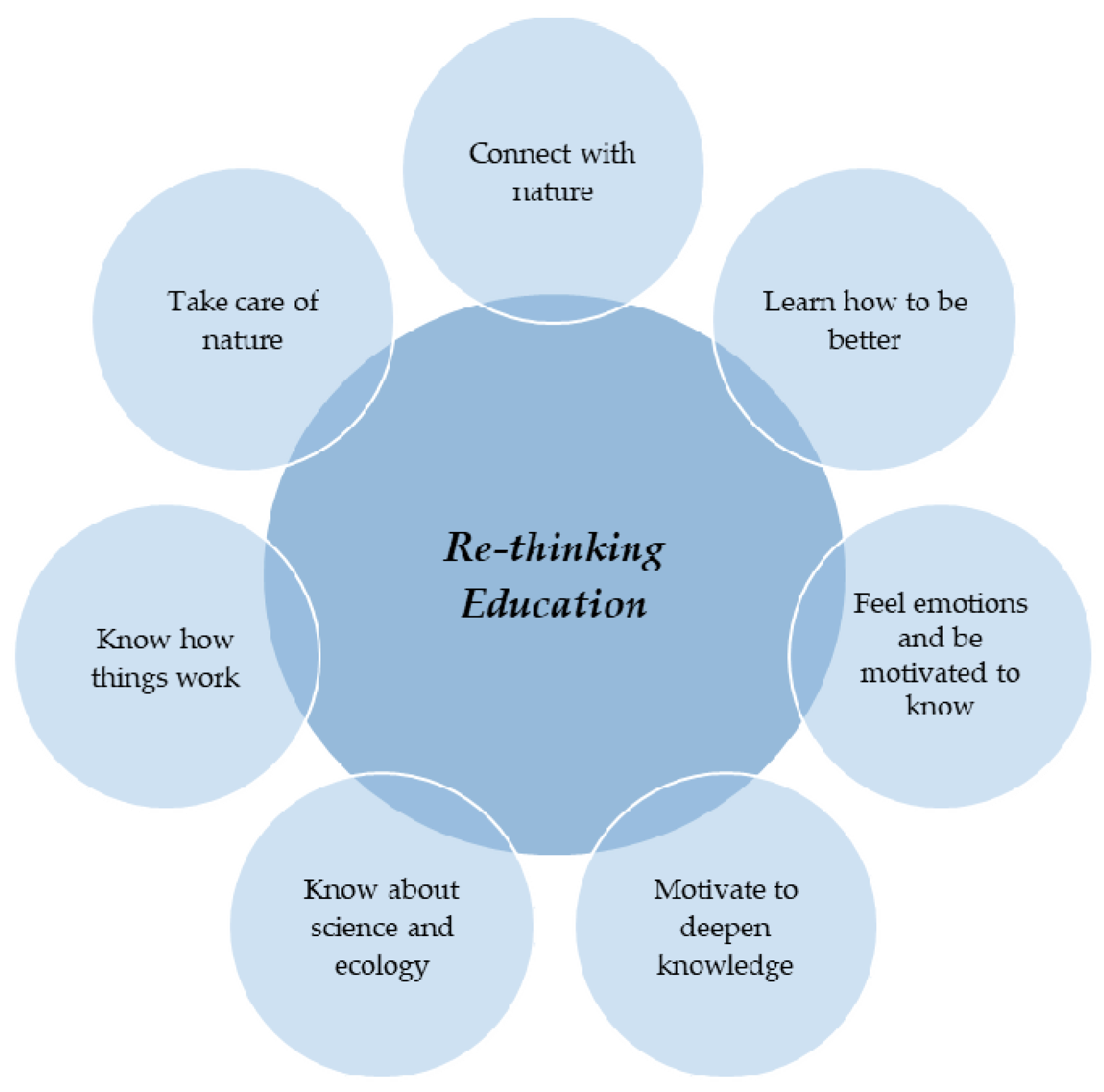

| Dimensions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-Term Purposes | ‘Connection and Consciousness’ | ‘Participation and Politics’ | ‘Re-thinking Education’ |

| Approaches to the environment Perspective of environmental problems What are they and how are they resolved? | Crisis of values that extends to the economy and politics Re-connect with principles of nature | Lack of adjustment of the ways of life and interests of different groups with respect to the planet’s limitations Reflection and action | Problems arising from “lack of information” Scientific information for informed decision-making |

| Causes of environmental problems | Crisis caused by human action without consciousness of tie with nature | Indifference and lack of empathy and participation | Weaknesses in formal education as regards scientific and ecological knowledge |

| Relation of humanity with the natural world | Principles of nature must guide human action towards a paradigm that is more reflexive and critical with respect to nature and society | Human decisions about the planet have catastrophic consequences for the environment and society | Important implications of our actions for our well-being and that of ecosystems |

| Teaching methods Ethical and political point of reference | Importance of the development of values and ethics for a change of paradigm | Ethics and political criticism | Ethics is key to the process but politics is not considered relevant at this level of education |

| Key subjects | Biology, ecology, and ethics | Social sciences, ethics and some elements of ecology | Biology, ecology, and ethics |

| Principal teaching method | Transition to co-construction based on scientific knowledge and experiential approach | Debates and projects related to topics agreed with students | Transition to co-construction based on scientific knowledge and experiential approach |

| Students | Transition to active critics seeking social change | Active critics seeking social change | Passive in transition to active co-construction |

| Planning and democracy | Central planning by teacher in transition to co-construction | Co-construction Teachers and students propose topics of interest for debate | Central planning by teacher in transition to co-construction |

| Goal/long-term objective. What is the purpose of my pedagogical practice for environmental education? | To re-connect the human being with nature and foster consciousness and change | To incorporate environmental issues to foster students’ participation with a view to social change | Re-thinking education |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Condeza-Marmentini, A.; Flores-González, L. Teachers’ Transgressive Pedagogical Practices in Context: Ecology, Politics, and Social Change. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6145. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216145

Condeza-Marmentini A, Flores-González L. Teachers’ Transgressive Pedagogical Practices in Context: Ecology, Politics, and Social Change. Sustainability. 2019; 11(21):6145. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216145

Chicago/Turabian StyleCondeza-Marmentini, Antonia, and Luis Flores-González. 2019. "Teachers’ Transgressive Pedagogical Practices in Context: Ecology, Politics, and Social Change" Sustainability 11, no. 21: 6145. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216145

APA StyleCondeza-Marmentini, A., & Flores-González, L. (2019). Teachers’ Transgressive Pedagogical Practices in Context: Ecology, Politics, and Social Change. Sustainability, 11(21), 6145. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216145