The Influence of Consumers’ Perceived Risks towards Eco-Design Packaging upon the Purchasing Decision Process: An Exploratory Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Eco-Design Packaging

- Design: All the stakeholders of the conceptualization of packaging (design, packaging industry, supply, logistics, research and development, and marketing) are taken into consideration from the beginning, to enable a comprehensive vision of the issues involved.

- Procurement: Eco-friendly materials are used (easy to disassemble, recyclable, and degradable).

- Manufacturing: The whole packaging system is optimized: Primary packaging (encouraging the end users/consumers), secondary packaging (filling the displays at points of sale), and tertiary packaging (facilitating the transport of a number of products).

- Consumption or usage: Consumer expectations are integrated: The convenience of use (rate of a refund, rate of opening/closing), the visualized information (brand name, country of manufacture, etc.), and the volume and the weight.

- End-of-life: The components of packaging should be easy to disassemble, recyclable, and degradable.

2.2. Effects of Packaging on Purchasing Decisions

2.3. Perceived Risk

2.4. Value in the Purchasing Decision Process

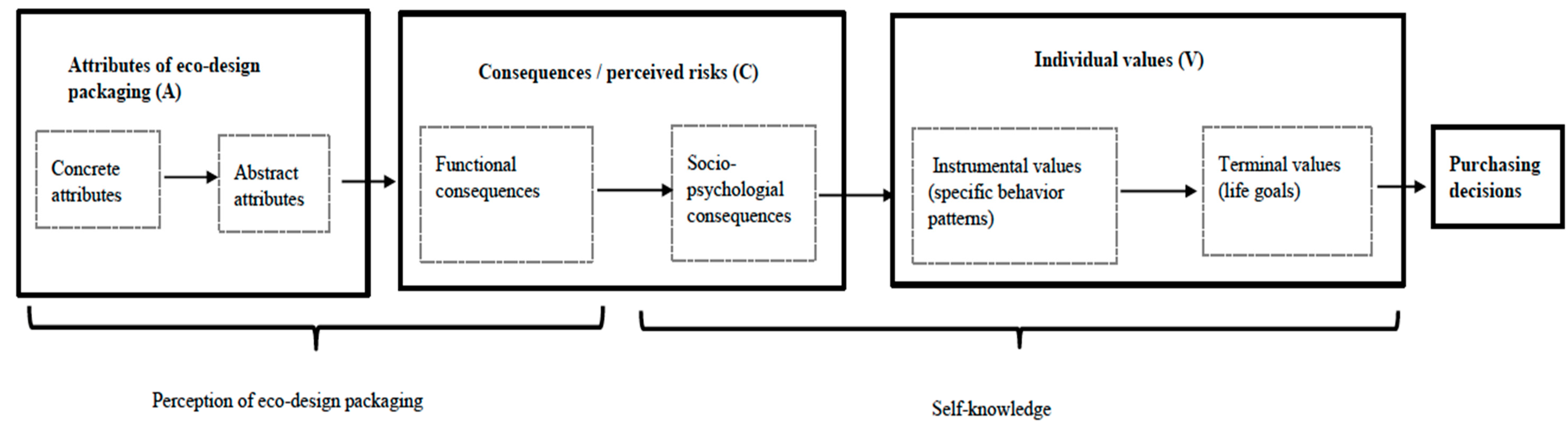

3. Conceptual Framework: The Means–End Chain Theory

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Data Analysis

5. Results

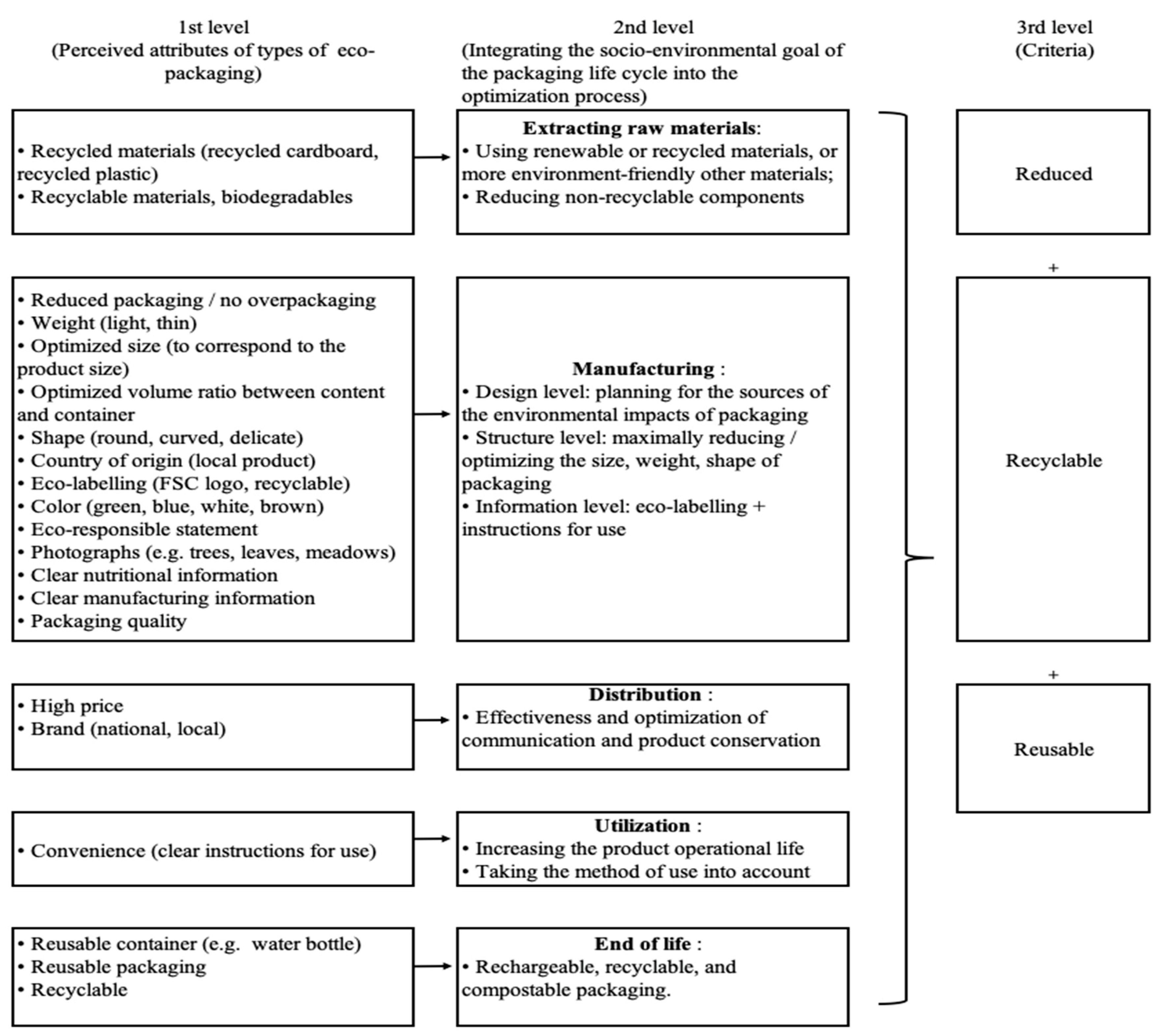

5.1. Perceptions of Eco-Design Packaging

- Some attributes are common to both perspectives:

- The packaging is made from recyclable materials or materials that are more environmentally friendly.

- The weight of the packaging ought to be lighter.

- The size is optimized (i.e., the content/container ratio is improved).

- The packaging’s color is green, blue, or transparent.

- The packaging shows an eco-label or other environmental label.

- Other attributes appeared in the consumers’ lists because of their lack of knowledge of some new concepts:

- From the consumers’ perspective, environmentally friendly materials comprise materials such as cardboard, paper, recycled plastic, and biodegradable materials.

- An optimized size and structure are incorporated into the optimization process, the content/container (product/packaging) ratio (such as an improved closing system), and the weight and/or volume optimization of the packaging components/elements.

- Some abstract attributes (i.e., attributes not necessary to describe the physical characteristics of eco-design packaging), such as the high price of eco-packaged products relative to the price of products in conventional packaging or brand images appearing to be significant to consumers.

5.2. Perceived Risks towards Eco-Design Packaging

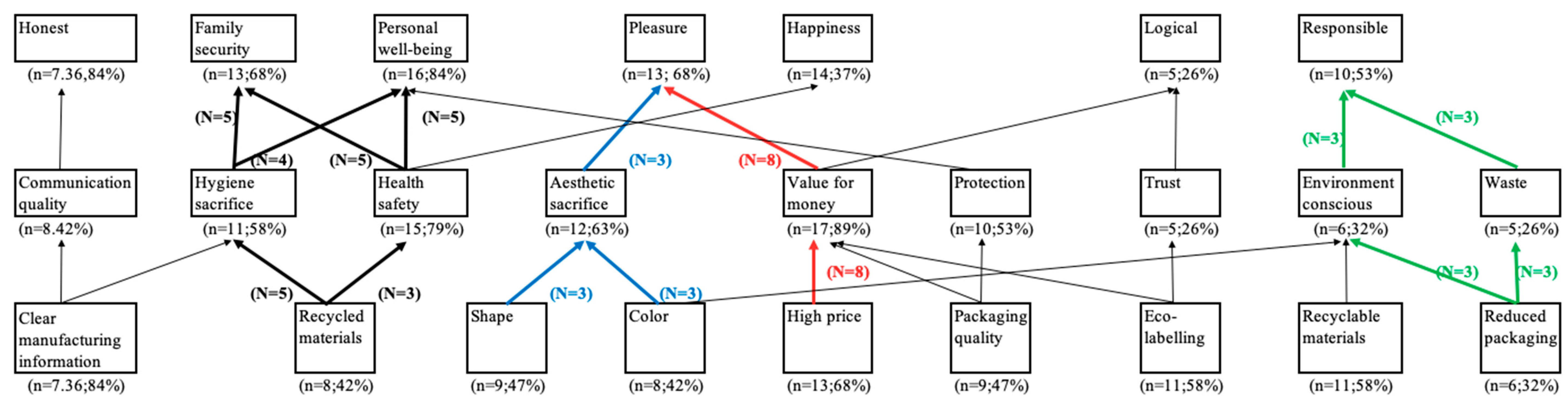

5.3. Major Orientations and Perceived Risks towards Eco-Design Packaging

- Segment 1—Eco-conscious consumers: The first segment includes consumers highly concerned by the socio-environmental risks of eco-design packaging (i.e., food waste, trust towards the product and the brand, practicality, respect for the environment). More precisely, two attributes of eco-design packaging distinguish Segment 1 from another: Recycled materials, reduce packaging/no overpackaging.

- Segment 2—Utilitarian-minded consumers: The second segment views as significant financial and functional risks of eco-design packaging. These consumers take value for money into account; they tend to find a compromise between the key packaging functions, the product price and life standard.

- Segment 3—Skeptical consumers: Segment 3 consumers are skeptics. They stress the communication function of eco-design packaging and link it with the protection function of packaging.

5.4. Impacts of the Perceived Risks towards Eco-design Packaging in the Decision-Making Process

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Methodological Contributions

6.3. Managerial Implications

6.4. Political Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 3 | 38% |

| Female | 5 | 63% | |

| Average age | 36 | ||

| Marital status | Single, never married | 2 | 25% |

| In a domestic partnership or civil union | 2 | 25% | |

| Married | 3 | 38% | |

| Divorced | 0 | ||

| Widowed | 1 | 13% | |

| Origin | Quebec | 4 | 50% |

| Other Provinces in Canada | 0 | ||

| Other Countries | 4 | 50% | |

| Education | No diploma | 0 | |

| High school graduate | 1 | 13% | |

| Certificate | 2 | 25% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 2 | 25% | |

| Master’s degree | 2 | 25% | |

| Ph.D. | 1 | 13% | |

| Number of Children | No child | 5 | 63% |

| 1 | 1 | 13% | |

| 2 | 1 | 13% | |

| More than 2 | 1 | 13% | |

| Total | 8 | 100% | |

Appendix B. Guide of the Focus Group

- A cheese bag made of 100% recycled plastic that is easy to reclose

- A water bottle that improves content/container (product/packaging) ratio (i.e., using the same quantity of 100% recycled rPET plastic contains more water).

- A box of granola bars that use less cardboard.

| Topics | Open–End Questions | Complementary Questions |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceptions regarding eco-design packaging attributes | What are your impressions regarding these packs? | |

| 2. Consequences relating consumption of eco-design packaging | What do you think about the initiative of eco-design packaging? | |

| 3. Evaluation criteria in purchasing decisio | Can eco-design packaging change your mind when you are shopping? |

|

Appendix C

| Variable | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 8 | 42% |

| Female | 11 | 58% | |

| Age | 18–24 | 6 | 32% |

| 25–34 | 10 | 53% | |

| 35–44 | 1 | 5% | |

| 45–54 | 2 | 11% | |

| Martial status | Single, never married | 10 | 53% |

| In a domestic partnership or civil union | 4 | 21% | |

| Married | 5 | 26% | |

| Divorced | 0 | 0% | |

| Widowed | 0 | 0% | |

| Origin | Quebec | 8 | 42% |

| Other Provinces in Canada | 0 | 0% | |

| Other Countries | 11 | 58% | |

| Education | No diploma | 0 | 0% |

| High school graduate | 2 | 11% | |

| Certificate | 1 | 5% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 2 | 11% | |

| Master’s degree | 13 | 68% | |

| Ph.D. | 1 | 5% | |

| Total | 19 | 100% | |

Appendix D

| A-C-V’s | Orientations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Attributes | Recycled materials (e.g., recycled cardboard, recycled plastic, biodegradable plastic, wood) | 0.047 | 1.213 | 0.091 |

| Recyclable materials | 0.099 | 0.063 | 0.013 | |

| Reduced packaging/no overpackaging | 0.205 | 0.6 | 0.293 | |

| Shape (round, curved, delicate) | 0.268 | 0.229 | 0.029 | |

| Eco-labeling (FSC logo, recyclable) | 0.008 | 0.035 | 0.272 | |

| Color (green, blue, transparent, white, brown) | 0.11 | 1.169 | 0.146 | |

| Clear manufacturing information | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.231 | |

| High price | 0.535 | 0.014 | 0.009 | |

| Packaging quality | 0.011 | 0.02 | 0.743 | |

| Consequences | Value for money | 0.002 | 0.087 | 0.085 |

| Protection effectiveness | 0 | 0.075 | 1.385 | |

| Communication quality (difficult to understand the information presented on the packaging) | 0.065 | 0.027 | 0.051 | |

| Hygiene/cleanliness sacrifice | 0.054 | 1.389 | 0.767 | |

| Health/health safety | 0.636 | 1.195 | 0.414 | |

| Pleasure during the consumer experience (hedonism) | 0.003 | 0.84 | 0 | |

| Practicality | 0.361 | 0.157 | 0.182 | |

| Respect for the environment | 0.736 | 0.708 | 0.11 | |

| Food waste | 0.026 | 0.648 | 0.405 | |

| Aesthetic sacrifice | 0.012 | 0.505 | 0.117 | |

| Trust/credibility towards the product and the brand | 0.496 | 0.438 | 0.51 | |

| Values | Capable (competent, effective) | 0.328 | 0.069 | 0.003 |

| Logical (coherent, rational) | 0 | 0.001 | 0.286 | |

| Intellectual (intelligent, thoughtful) | 0.003 | 1.018 | 0.241 | |

| Honest (sincere, frank) | 0.019 | 1.847 | 0.807 | |

| Responsable (accountable, reliable) | 0.033 | 5.858 | 0.498 | |

| Enjoyment and excitement/pleasure (pleasant unhurried life) | 1.427 | 0.084 | 0.003 | |

| Happiness (satisfaction) | 0.271 | 0.28 | 0.025 | |

| Family security (taking good care of loved ones) | 0.229 | 1.774 | 0.112 | |

| Inner harmony (for personal well-being/security) | 0.181 | 1.299 | 0.065 | |

Appendix E

| Term | Explanation | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Means–end chain (or cognitive chaining) | The term “Means–end chain” is used to describe the theoretical framework and research method. However, the term “cognitive chaining” is used to presented research method and results. Cognitive chaining describes the connection between product attributes (the “means”), the consequences consumers derive from those, and the potential links with consumers’ values (the “end”). More precisely, cognitive chaining links three successive levels of abstraction: Attributes, consequences, and values (A-C-V′s structure). Cognitive chaining can identify the consumer purchasing decision process and behavior patterns associated with a product (i.e., eco-design packaging). | Figure 1 |

| Consequence | The term “consequence” only refers to second a level variable (A-C-V’s). It is measured by 17 items. | Table 1 |

| Risk | The term “risks” refers to the aggregated concept from the findings. The authors use the term “risks” to describe the consumer segments (Table 6) and their risk-oriented consumption patterns (Figure 3). | Table 6 Figure 3 |

| Orientation | The term “orientation” refers to the typology of A-C-V’s structure. For instance, the orientation A3-C3-V3 in the 3rd line of Table 6 corresponds to: A (Clear manufacturing information)–C (Hygiene/cleanliness sacrifice, Communication quality)–V (Honest, Responsible). | Table 6 |

| Consumption segment | The term “consumption segment” describes a group of consumers who share the common characteristics. This study identifies three consumer segments based on their perceived risk associated with eco-design packaging: (1) Eco-conscious consumers, (2) Utilitarian-minded consumers, and (3) Skeptical consumers. | Table 6 |

| Consumption pattern | The term “consumption pattern” describes consumer consumption A-C-V structure based on the perceived risks associated with eco-design packaging. This study revealed four consumption patterns: (1) a functional and physical risks-oriented consumption pattern, (2) a life standard risk-oriented consumption pattern, (3) a financial risk-oriented consumption pattern, and a (4) socio-environmental risk-oriented consumption pattern. | Figure 3 |

References

- Rundh, B. Packaging design: Creating competitive advantage with product packaging. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 988–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brach, S.; Walsh, G.; Shaw, D. Sustainable consumption and third-party certification labels: Consumers’ perceptions and reactions. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polito, T. Éco-conception des emballages. Techniques de L’ingénieur; L’Entreprise Industrielle: Saint-Denis, France, 2000; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Magnier, L.; Crié, D. Communicating packaging eco-friendliness. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F. L’impact d’un Packaging Simple sur la Perception du Produit. In Proceedings of the 14ième Colloque Doctoral de l’Association Française de Marketing, 13 et 14 mai 2014 à Montpellier, Montpellier, France, 13 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, J.-C.; Chang, H.-T.; Chen, S.-B. Factor Analysis of Packaging Visual Design for Happiness on Organic Food—Middle-Aged and Elderly as an Example. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnier, L.; Schoormans, J. Consumer reactions to sustainable packaging: The interplay of visual appearance, verbal claim and environmental concern. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 44, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzan, G.; Cruceru, A.; Bălăceanu, C.; Chivu, R.-G. Consumers’ Behavior Concerning Sustainable Packaging: An Exploratory Study on Romanian Consumers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnier, L.; Schoormans, J.; Mugge, R. Judging a product by its cover: Packaging sustainability and perceptions of quality in food products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 53, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleim, M.; Smith, J.; Andrews, D.; Cronin, J. Against the Green: A Multi-method Examination of the Barriers to Green Consumption. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ogden, D.T. To buy or not to buy? A social dilemma perspective on green buying. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaoikonomou, E.; Ryan, G.; Ginieis, M. Towards a Holistic Approach of the Attitude Behaviour Gap in Ethical Consumer Behaviours: Empirical Evidence from Spain. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2011, 17, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett-Baker, J.; Ozaki, R. Pro-environmental products: Marketing influence on consumer purchase decision. J. Consum. Mark. 2008, 25, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, K.; Petersen, L.; HöRisch, J.; Battenfeld, D. Green thinking but thoughtless buying? An empirical extension of the value-attitude-behaviour hierarchy in sustainable clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rayp, G. Do Consumers Care about Ethics? Willingness to Pay for Fair-Trade Coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.; Potter, S. The adoption of cleaner vehicles in the UK: Exploring the consumer attitude–action gap. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; Devinney, T. Do What Consumers Say Matter? The Misalignment of Preferences with Unconstrained Ethical Intentions. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T. Impacts des Perceptions de L’éco-Packaging sur les Achats de Produits Éco-Emballés. Master’s Thesis, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- GreenUXlab ESG UQAM. Baromètre Greenuxlab/MBA Recherche des Nouvelles Tendances de Consommation en Commerce de Détail; GreenUXlab ESG UQAM: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, C.; Durif, F.; Roy, J. Buying Socially Responsible Goods: The Influence of Perceived Risks Revisited. World Rev. Bus. Res. 2011, 1, 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Luchs, M.G.; Naylor, R.W.; Irwin, J.R.; Raghunathan, R. The sustainability liability: Potential negative effects of ethicality on product preference. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, T.J.; Gutman, J. Laddering theory, method, analysis, and interpretation. J. Advert. Res. 1988, 28, 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Valette-Florence, P. Introduction à l’analyse des chaînages cognitifs. Rech. Appl. Mark. 1994, 9, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, J. Analyzing consumer orientations toward beverages through means–end chain analysis. Psychol. Mark. 1984, 1, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauer, E.; Wohner, B.; Heinrich, V.; Tacker, M. Assessing the Environmental Sustainability of Food Packaging: An Extended Life Cycle Assessment including Packaging-Related Food Losses and Waste and Circularity Assessment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesen, S.; Bey, N.; Niero, M. Environmental sustainability of liquid food packaging: Is there a gap between Danish consumers’ perception and learnings from life cycle assessment? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, S.; Beckenuyte, C.; Butt, M.M. Consumers’ behavioural intentions after experiencing deception or cognitive dissonance caused by deceptive packaging, package downsizing or slack filling. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; François, J.; Durif, F. How Consumers React to Environmental Information: An Experimental Study. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2017, 29, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaiman, K.; Ortega, D.L.; Garnache, C. Perceived barriers to food packaging recycling: Evidence from a choice experiment of US consumers. Food Control 2017, 73, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Wikström, F.; Wetter-Edman, K.; Kristensson, P. Decisions on recycling or waste: How packaging functions affect the fate of used packaging in selected Swedish households. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Giorgi, S.; Sharp, V.; Strange, K.; Wilson, D.C.; Blakey, N. Household waste prevention—A review of evidence. Waste Manag. Res. 2010, 28, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Predicting household food waste reduction using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 101, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Monetary Incentives and Recycling: Behavioural and Psychological Reactions to a Performance-Dependent Garbage Fee. J. Consum. Policy 2003, 26, 197–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagnano, G.A.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. Influences on Attitude-Behavior Relationships: A Natural Experiment with Curbside Recycling. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Karakas, F.; Sarigöllü, E. Exploring pro-environmental behaviors of consumers: An analysis of contextual factors, attitude, and behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3971–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiesser, P. Eco-efficience, analyse du cycle de vie & éco-conception: Liens, challenges et perspectives. In Annales des Mines—Responsabilité et Environnement; Cairn: Paris, France, 2012; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, T.; Ertz, M.; Durif, F. Examination of a Specific Form of Eco-design. Int. J. Manag. Bus. 2017, 8, 50–74. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.R. Marketing Communications: An Integrated Approach, 4th ed.; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P. Marketing Management, 14th ed.; Pearson France: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, R.L. The Communicative Power of Product Packaging: Creating Brand Identity via Lived and Mediated Experience. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2003, 11, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettie, R.; Brewer, C. The verbal and visual components of package design. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2000, 9, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantin-Sohier, G.; Bree, J. L’influence de la couleur sur la perception des traits de personnalité de la marque. In Revue Française du Marketing; Sage: Paris, France, 2004; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pantin-Sohier, G. L’influence du packaging sur les associations fonctionnelles et symboliques de l’image de marque. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2009, 24, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B. Can package size accelerate usage volume? J. Mark. 1996, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Van Ittersum, K. Bottoms Up! The Influence of Elongation on Pouring and Consumption Volume. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, M. The influence of shape on product preferences. Adv. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 559. [Google Scholar]

- Raghubir, P.; Greenleaf, E.A. Ratios in proportion: What should the shape of the package be? J. Mark. 2006, 70, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Raghubir, P. Les bouteilles peuvent-elles être transcrites en volumes? L’effet de la forme de l’emballage sur la quantité à acheter. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2006, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.-P. Vers une clarification du concept de packaging: Nécessité d’une approche interdisciplinaire. In Proceedings of the 16ème Colloque National de la Recherche dans les IUT, Angers, France, 9 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt, G.M.; Dobscha, S. L’efficacité de la participation consciente à promouvoir la durabilité sociale. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2014, 29, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François-lecompte, A.; Valette-florence, P. Mieux connaitre le consommateur socialement responsable. Décis Mark. 2006, 41, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, J.; Johns, N.; Kilburn, D. An Exploratory Study into the Factors Impeding Ethical Consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volle, P. Le concept de risque perçu en psychologie du consommateur: Antécédents et statut théorique. Rech. Appl. Mark. 1995, 10, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valette-Florence, P. Analyse structurelle comparative des composantes des systèmes de valeurs selon Kahle et Rokeach. Rech. Appl. Mark. 1988, 3, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, L.R.; Kennedy, P. Using the List of Values (LOV) to Understand Consumers. J. Consum. Mark. 1989, 6, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, L.B.; Szybillo, G.J.; Jacoby, J. Components of perceived risk in product purchase: A cross-validation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pin, A.-C.; Picot-Coupey, K.; Droulers, O. Mesurer le risque perçu à <jouer responsable>. Journal de Gestion et D’économie Médicales 2014, 32, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlena, W.J.; Desarbo, W.S. On the Measurement of Perceived Consumer Risk. Decis. Sci. 1991, 22, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ferran, F. Différentiation des Motivations à la Consommation de Produits Engagés et Circuits de Distribution Utilisés, Application à la Consommation de Produits Issus du Commerce Équitable; Ecole Dotorale d’Economie et de Gestion: Aix-en-Provence, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Young, S.; Feigin, B. Using the benefit chain for improved strategy formulation. J. Mark. 1975, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, J. A means-end chain model based on consumer categorization processes. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.C.; Reynolds, T.J. Understanding consumers’ cognitive structures: Implications for advertising strategy. Advert. Consum. Psychol. 1983, 1, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gengler, C.E.; Klenosky, D.B.; Mulvey, M.S. Improving the graphic representation of means-end results. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valette-Florence, P.; Ferrandi, J.-M.; Roehrich, G. Apport des chaînages cognitifs à la segmentation des marchés. Décis. Mark. 2003, 32, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973; Volume 438. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, T.J.; Gutman, J. Advertising is image management. J. Advert. Res. 1984, 24, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Brieu, M.; Durif, F.; Roy, J.; Prim-Allaz, I. Valeurs et risques perçus du tourisme durable-le cas du SPA Eastman. Rev. Fr. Mark. 2011, 232, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rundh, B. The multi-faceted dimension of packaging: Marketing logistic or marketing tool? Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoluci, G.; Trystram, G. Eco-concevoir pour l’industrie alimentaire: Quelles spécificités ? Marché Organ. 2013, 17, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berneman, C.; Lanoie, P.; Plouffe, S.; Vernier, M.-F. Démystifier la mise en place de l’écoconception. Gestion 2013, 38, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conseil National de l’emballage. Eco-Design of Packaged Products: Methodological Guide; Conseil National de l’emballage: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kahle, L.R.; Beatty, S.E.; Homer, P. Alternative measurement approaches to consumer values: The list of values (LOV) and values and life style (VALS). J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.; Birks, D. Marketing Research: An Applied Approach, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, D.; Birtwistle, G.; Macedo, N. Food retail positioning strategy: A means-end chain analysis. Br. Food J. 2003, 105, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Wiedenfeld and Nicholson: London, UK, 1967; Volume 24, pp. 288–304. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Thomas, J.B.; Clark, S.M.; Chittipeddi, K. Symbolism and strategic change in academia: The dynamics of sensemaking and influence. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, K.G.; Gioia, D.A. Identity Ambiguity and Change in the Wake of a Corporate Spin-off. Adm. Sci. Q. 2004, 49, 173–208. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. Corp SPSS Statistics for Windows, 23.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roullet, B.; Droulers, O. Pharmaceutical Packaging Color and Drug Expectancy. Adv. Consum. Res. 2004, 32, 164–171. [Google Scholar]

- Krider, R.E.; Raghubir, P.; Krishna, A. Pizzas: π or square? Psychophysical biases in area comparisons. Mark. Sci. 2001, 20, 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkes, V.; Matta, S. The effect of package shape on consumers’ judgments of product volume: Attention as a mental contaminant. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, J.F.; Stone, E.R. Risk appraisal. Risk-Tak. Behav. 1992, 92, 49–85. [Google Scholar]

- Einhorn, H.J.; Hogarth, R.M. Decision making: Going forward in reverse. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1987, 65, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, S. The Measurement of the Effect of a New Packaging Material Upon Preference and Sales. J. Bus. Univ. Chic. 1950, 23, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, C.; Baker, R.C. Convenience Food Packaging and the Perception of Product Quality. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoormans, J.P.L.; Robben, H.S.J. The effect of new package design on product attention, categorization and evaluation. J. Econ. Psychol. 1997, 18, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, N.; Ampuero, O. The Role of Packaging in Positioning an Orange Juice. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2007, 13, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ. Behav. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model and Personal Health Behavior; Slac:k: Thorefare, NJ, USA, 1974; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R.W. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change1. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, R.W. Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. Soc. Psychophysiol. 1983, 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kassarjian, H.H. Incorporating ecology into marketing strategy: The case of air pollution. J. Mark. 1971, 35, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuca, L.B.; Montréal, H.E.C. L’importance Accordée au Prix du Produit en Relation Avec ses Attributs Écologiques: Une Analyse Conjointe de Préférences; HEC Montreal: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Couégnas, N.; Bertin, E. Solutions Sémiotiques; Editions Lambert-Lucas: Limoges, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley, R.P.; Harkins, L.E. Functional and attention-getting effects of color on graphic communications. Percept. Motor Skills 1970, 31, 851–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaen, V.; Chumpitaz, C.R. L’impact de la responsabilité sociétale de l’entreprise sur la confiance des consommateurs. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2008, 23, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, T.J.; Olson, J.C. Understanding Consumer Decision Making: The Means-End Approach to Marketing and Advertising Strategy; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wikström, F.; Williams, H.; Venkatesh, G. The influence of packaging attributes on recycling and food waste behaviour—An environmental comparison of two packaging alternatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Éco Entreprises Québec. Quebecers’ Relationship with Packaging: Importance Attached to Environmental Criteria for Consumer Product Purchasing; GreenUXlab ESG UQAM: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, H.; Wikström, F. Environmental impact of packaging and food losses in a life cycle perspective: A comparative analysis of five food items. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikström, F.; Williams, H.; Trischler, J.; Rowe, Z. The Importance of Packaging Functions for Food Waste of Different Products in Households. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanes, E.; Oestergaard, S.; Hanssen, O. Effects of Packaging and Food Waste Prevention by Consumers on the Environmental Impact of Production and Consumption of Bread in Norway. Sustainability 2019, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Research Question | Objective of Each Step | Data Collection | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Generating the relevant attributes, consequences, and values associated with eco-design packaging in terms of six levels of cognitive chaining: Concrete attributes, abstract attributes, functional consequences, socio-psychological consequences, instrumental values, and terminal values. |

| Generate an initial list of A-V-C’s from existing literature. This initial list was complemented by focus group. | Literature Review | |

| Focus group (n = 8) | |||

| Step 2: Constructing the individual cognitive chains associated eco-design packaging. | To answer research question 3: Segment consumers based on their perceived risks of eco-design packaging. | Identify the dominant items of Attributes, Consequences, and Values. | Face-to-face individual, laddering interviews with pre-coded cards (n = 19) | Table 6. Consumer segments according to perceived risks. |

| Step 3: Constructing an aggregated hierarchical map. | To answer research question 4: Explore the potential eco-packed product consumption patterns based on perceived risks. | Clarify the linkage between Attributes, Consequences, and Values. | Figure 3. Aggregated hierarchical map of risk-oriented consumption patterns. |

| Item | Concrete Attributes | Item | Functional Consequences | Item | Instrumental Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC1 | Recycled materials (recycled cardboard, recycled plastic, biodegradable plastic, wood, etc.) | CF1 | Value for money | VI1 | Capable (competent, effective) |

| AC2 | Recyclable materials | CF2 | Protection effectiveness | VI2 | Logical (coherent, rational) |

| AC3 | Biodegradable materials | CF3 | Communication quality (difficult to understand the information presented on the packaging) | VI3 | Intellectual (intelligent, thoughtful) |

| AC4 | Reduced packaging/no overpackaging | CF4 | Not easy to consume the product | VI4 | Honest (sincere, frank) |

| AC5 | Weight (light, thin) | CF5 | Food waste | VI5 | Environment-friendly |

| AC6 | Optimized size (to correspond to the product size) | CF6 | Hygiene/cleanliness sacrifice | VI6 | Responsible (accountable, reliable) |

| AC7 | Optimized volume ratio between content and container | CF7 | Health/health safety | VI7 | Open-minded |

| AC8 | Shape (round, curved, delicate) | CF8 | Lack of time to become used to the new packaging | ||

| AC9 | Country of origin (local product) | CF9 | Aesthetic sacrifice | ||

| AC10 | Eco-labeling (FSC logo, recyclable) | ||||

| AC11 | Color (green, blue, transparent, white, brown) | ||||

| AC12 | Eco-responsible statement | ||||

| AC13 | Photographs (e.g., trees, leaves, meadows) | ||||

| AC14 | Clear nutritional information | ||||

| AC15 | Clear manufacturing information | ||||

| AC16 | Reusable container (e.g., water bottle) | ||||

| AC17 | Reusable packaging | ||||

| AC18 | Recycled | ||||

| AC19 | Recyclable | ||||

| Item | Abstract Attributes | Item | Psycho-Sociological Consequences | Item | Terminal Values |

| AA1 | High price | CP1 | Trust/credibility towards the product and the brand | VT1 | Feeling of accomplishment (sustainable contribution) |

| AA2 | Brand (national, local) | CP2 | Pleasure during the consumer experience (hedonism) | VT2 | Enjoyment and excitement/pleasure (pleasant unhurried life) |

| AA3 | Packaging quality | CP3 | Way of life/quality of life | VT3 | Happiness (satisfaction) |

| AA4 | Convenience (clear instructions for use) | CP4 | Practicality | VT4 | Family security (taking good care of loved ones) |

| CP5 | Self-concept | VT5 | Inner harmony (for personal well-being/security) | ||

| CP6 | Respect for the environment | VT6 | Sense of belonging | ||

| CP7 | Variety | ||||

| CP8 | Collective well-being (collective satisfaction) |

| Life-Cycle | Industry View | Consumer View |

|---|---|---|

| Raw material acquisition and preprocessing | Recycled cardboard or Fiber | Recycled materials (recycled cardboard, recycled plastic) |

| Clear indication of disposing | Recyclable or biodegradable materials | |

| Partially recycled cardboard | ||

| 100% Recycled cardboard | ||

| Cardboard or paper with certification FSC, SFI, CSA, PEFC | ||

| Recycled plastic | ||

| Bamboo | ||

| Multi-layer Cardboard | ||

| Styrofoam (e.g., tray for meat) | ||

| Molded pulp (e.g., egg carton) | ||

| Degradable plastics | ||

| Woods | ||

| Packaging with a reduced number of non-Recyclable components | ||

| Manufacturing | Packaging that reduces the volume by compaction or vibration | Reduced packaging/no Overpackaging |

| Reduced packaging of the length of the seals | Weight (light, thin) | |

| Reduce or eliminate waste generated by closure and tamper evident systems | Optimized size (correspond to the product size) | |

| Packaging that reduces or eliminates waste generated by closure and tamper evident systems | Optimized volume ratio between content and container | |

| Weight optimization of the packaging components/elements | Shape (round, delicate) | |

| Volume optimization of the packaging components/elements | Country of origin (local product) | |

| Shape (round, curved, delicate) | Eco-labeling (FSC logo, recyclable) | |

| Optimized volume ratio content/container | Color (green, blue, transparent, white, brown) | |

| Eco-responsible statement | ||

| Optimized volume ratio of palletization | Photographs (e.g., trees, leaves, meadows) | |

| Eco-labeling for fabrication process | Clear nutritional information | |

| Clear nutritional information | Clear manufacturing information | |

| Clear manufacturing information | Packaging quality | |

| Clear user manual | ||

| Distribution | Protecting the product components in transportation | High price |

| Efficient reclosing function to protect the product | Brand (national, local) | |

| Utilization | Increasing the product operational life | Convenience (clear instructions for use) |

| Integrating the need of the consumer into packaging design process | ||

| User-friendly | ||

| End of life | Primary packaging by accepting refills for reuse | Reusable container |

| Composable | Reusable packaging | |

| Recyclable | Recyclable | |

| Reducing or avoiding waste |

| Functional Risks | Verbatim Statements |

|---|---|

| (1) Value for money | Participant #7: Cost is important to me and the extra cost is constraining, but the bottle of water, I’m going to buy it. But I’m not buying it because it’s recyclable but because it’s the cheapest in my grocery store. Participant #4: Me too, what’s important is the product price, if there’s a two-dollar difference, I’ll buy the cheapest of the two. Participant #3: Price first and packaging last. |

| (2) Protection effectiveness | Participant #2: Yes, it’s really annoying to throw away, so the next time, I buy smaller quantities or when I understand that a product does not keep well, the next time I go to the store, I’ll buy another brand. |

| (3) Communication (difficult to understand the information presented on the packaging) | Participant #1: It’s hard to understand the definition of rPET (...), it’s hard to know what standard is used. |

| (4) Food waste | Participant #8: Sometimes I throw away almost half of what I buy, lots of bread, but also cheese and sometimes meat. It often happens because I plan large quantities or else I buy on special but I don’t eat everything. |

| (5) Sacrifice of hygiene/cleanliness | Participant #7: [Packaging] does not really influence my decision to buy, they should indicate more clearly the efforts they make to make packaging cleaner. |

| (6) Health/health safety | Participant #1: They say we should not reuse water bottles. Participant #7: I also look for the sell-by-date when I buy. Participant #6: I take packaging that’s not harmful to the product (...) |

| (7) Lack of time to become used to the new packaging | Participant #8: It depends on whether it’s an emergency purchase or when I go shopping, if I have time, I then look at the products and the packaging, but if it’s an emergency, I go straight to a brand I know. Participant #7: We did it last winter with my flat mates, but we stopped quickly because it’s too time-consuming; I prefer buying small quantities even if it means going shopping more often. Participant #4: Even if you plan in advance, in fact you never manage it, you never have the time to do what you’ve planned. Participant #1: I don’t read the labels, I often take the product because I know it. Participant #7: Sometimes I switch products, particularly with the new products, but then there are brands I will never change or else just once so I can compare. |

| (8) Aesthetic sacrifice | Interviewee: I think that the water bottle is not very pretty, [the shape] is not feminine. |

| Psycho-Sociological Risks | Verbatim Statements |

| (9) Trust/credibility towards the product and the brand | Participant #3: I’m suspicious of all this marketing related to environmental products. Participant #7: I’m a little suspicious of all this (eco-packaged products/green products) and then there’s the price, but with equal products and equal price, then I can try this product. |

| (10) Way of life/quality of life | Participant #6: (...) I often buy organic food, but the problem is it doesn’t keep so well. I slice my vegetables and I pop them into the freezer. |

| (11) Respect for the environment | Participant #1: For me, the environmental impact is important. |

| Orientations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impairment Index | Score | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Attributes | 0.145 | 0.030 | 0.046 | 0.068 |

| Consequences | 0.132 | 0.022 | 0.026 | 0.084 |

| Values | 0.179 | 0.019 | 0.028 | 0.132 |

| Mean | 0.152 | 0.024 | 0.034 | 0.095 |

| Adequacy index | 2.848 | |||

| Eigenvalues | 0.976 | 0.966 | 0.905 | |

| Consumer Segment * | Attributes | Consequences | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eco-conscious consumers: Socio-environmental risks | • Recycled materials (recycled cardboard, recycled plastic, biodegradable plastic, wood, etc.) | • Food waste | • Capable (competent, effective) |

| • Reduced packaging/no overpackaging | • Trust/credibility towards the product and the brand | • Logical (coherent, rational) | |

| • Practicality | • Intellectual (intelligent, thoughtful) | ||

| • Respect for the environment | • Environment-friendly | ||

| Utilitarian-minded consumers: Functional, financial, and life-standard risks | • Recyclable materials | • Value for money | • Open-minded |

| • Shape (round, curved, delicate) | • Protection effectiveness | • Enjoyment and excitement/pleasure (pleasant unhurried life) | |

| • Eco-labeling (FSC logo, recyclable) | • Health/health safety | • Happiness (satisfaction) | |

| • Color (green, blue, transparent, white, brown) | • Aesthetic sacrifice | • Family security (taking good care of loved ones) | |

| • High price | • Inner harmony (for personal well-being/security) | ||

| • Packaging quality | |||

| Skeptical consumers: Physical risks | • Clear manufacturing information | • Hygiene/cleanliness sacrifice | • Honest (sincere, frank) |

| • Communication quality (difficult to understand information presented on the packaging) | • Responsible (accountable, reliable) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, T.; Durif, F. The Influence of Consumers’ Perceived Risks towards Eco-Design Packaging upon the Purchasing Decision Process: An Exploratory Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216131

Zeng T, Durif F. The Influence of Consumers’ Perceived Risks towards Eco-Design Packaging upon the Purchasing Decision Process: An Exploratory Study. Sustainability. 2019; 11(21):6131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216131

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Tian, and Fabien Durif. 2019. "The Influence of Consumers’ Perceived Risks towards Eco-Design Packaging upon the Purchasing Decision Process: An Exploratory Study" Sustainability 11, no. 21: 6131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216131

APA StyleZeng, T., & Durif, F. (2019). The Influence of Consumers’ Perceived Risks towards Eco-Design Packaging upon the Purchasing Decision Process: An Exploratory Study. Sustainability, 11(21), 6131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216131