Abstract

The fact that the water resource governor has to allocate limited water resources to two competing agricultural water users under the administrative system (AS) leads to a principal-agent issue. Hence, this paper constructs a two-stage performance-based allocation mechanism to motivate two competing water users (referred to as the agents) to act in accordance with the interests of the governor (referred to as the principal). This mechanism is about the interaction between the governor and two water users. The governor aims to improve water resources allocation efficiency and balance economic and environmental development, while each agricultural user focuses on the overall amount of water resources they have to operate and would like to ignore environment protection issues. Besides, the total water resources invested into production or environment is two water users’ private information, which is unknown to the governor. In the first stage, the governor allocates water resources between two users according to their previous performances, including production and environmental aspects. Results indicate that the equilibrium state of this mechanism could encourage two water users to focus on production and environment performances simultaneously and to help the governor transfer the pollution cost to two water users under the external of pollution cost, which motivates them to compete for available water resources. This competition between two users will directly affect users’ behaviors. These results could improve water resources allocation efficiency significantly and realize the sustainability of water resources in the agricultural field under the current AS. This perspective could also provide a new insight for the management of agricultural water resources allocation and offer relative decision support to relative governors.

1. Introduction

Water resources play a crucial role in the agricultural sector, accounting for the largest share of available water resources all over the world [1]. Therefore, maintaining the sustainability of water resources has a great impact on agricultural development, which also requires the joint efforts of the governor and water users under the current water crisis [2]. Currently, the governor has to allocate limited water resources to two competing agricultural water users to realize water resources utility under the administrative system (AS) [3], which leads to the principal-agent issue. This issue is about how the governor (referred to as the principal) motivates the two water users (referred to as the agents) to realize the water resources sustainability, to compete for limited water resources and to improve allocation efficiency under the current water crisis.

Currently, water crisis and the issue of inefficient water usage have become severe challenges to social-economic-environmental sustainability development [4]. The rapidly increasing population increases water demand [5], and climate change, economic growth, and environmental protection also need more water resources, further deteriorating the water crisis [6]. Besides, water markets do not often function efficiently in practice [7] because the features of some water rights are not designed for market transactions and, in particular, the impact of hydrological uncertainty is not adequately considered [8]. Hence, the traditional agricultural water allocation system takes the form of the administrative system [9] where water is allocated mainly according to the experience of the governor, resulting in water allocation inefficiency. Therefore, it is urgent to introduce other mechanisms in combination with AS to improve the efficiency of agricultural water resources allocation and balance economic–environmental development so as to maintain sustainable development of agricultural water resources and ease water crisis.

Until now, many scholars have studied various aspects related to water resources allocation management, covering optimization issue, game theory issue, incentive mechanism issue, and penalty-reward mechanism issue. Studies related to optimization methods mainly focus on decision-making problems [10], addressing issues of the optimal allocation of water quantity or water quality but ignoring multi-party decision-making issues. Studies related to game theory could identify and interpret the behaviors of different parties of water resource problems and describe interactions between different parties [11], which could address conflicts, analyze behaviors of stakeholders and promote cooperation. Madani K [11] uses prisoner’s dilemma for understanding or resolving water conflicts involving multiple criteria and decision-makers. Wenyi Du et al. [12] introduce the two-stage Stackelberg game to develop a chain-to-chain competition model between two water suppliers, which is based on the supply chain to provide insights into the sustainability of water resource management. Said Shakib Atef et al. [13] formulate a mechanism for transforming conflict into cooperation among transboundary water management by enabling upstream and downstream states to negotiate for a win-win situation. Yong Zeng et al. [14] use a hybrid game theory and mathematical programming model to solve trans-boundary water conflicts between two cities in China. Zanjanian H et al. [15] take the governorship as the third party to address the conflict of multi-shareholders based on game theory. These studies differ from those using optimization methods and do not involve asymmetric information issues. Incentive mechanism [16], which considers conflicts of interests and asymmetric information between players, is an important tool for water resources management, which is also used in this paper. In terms of incentive mechanism, Sheng J and Webber M [17] use payments for watershed services to urge all participants to realize appropriate water governance in the south–north water transfer project related to water quality and ecological aspect. Kahn M E et al. [18] introduce political promotion criteria to impel local government to control water pollution along transboundary rivers. J. Novak et al. [19] employ the information and communication technology-system(ICT-system) for behavioral change to stimulate consumers to save water. Besides, economic incentive [20] is also used in this area. Penalty-based mechanism [21], or penalty-reward method, means to reward good performance or punish poor performance respectively, which provides a prospective way to solve multi-agents system (MAS) problems in various areas. Penalty methods have been used to optimize the operation of pumping for water distribution system [22]. Inalhan, G. [23] applies a penalty-based method to solve the coordination problem of interconnected nonlinear discrete-time dynamic systems with multiple decision-makers, an initiative decentralizing optimization framework widely used in many areas. Yang, Y.-C.E. et al. [24] use this optimization method to analyze a MAS problem related to watershed management aspect, developing a better decision-support tool for allocating water between human society and ecosystems. Mohammadnezhad-Shourkaei H [25] introduces this mechanism on the basis of performance-based regulation in the electricity industry, an effective method to improve the service reliability. Zhao J et al. [3] also use a penalty-based mechanism, a so-called cross-subsidy mechanism in the administration system, to analyze agent-based modeling framework related to the water allocation system. Although the penalty-based mechanism takes different forms, minimizes penalty, or maximizes utility, these examples show that the mechanism is an effective method in energy management under competition and MAS.

However, these applications do not cover the key point in this paper, that is, the multi-stage penalty and reward issues. Hence, this paper sets up a two-stage performance-based mechanism based on principal-agent theory [26], which could improve the efficiency of allocation and balance economic–environment development from the governor’s perspective. The mechanism involves the interaction between the governor and two water users. It also considers conflicts of interests and asymmetric information between the governor and two water users, as well as the competition between two water users. The governor aims to maximize the system-level performances, such as system-wide economic benefits, equity, and environmental performances [27,28], while each water user only focuses on their economic revenues and thirsts for water resources as much as possible [29]. To make things worse, the governor cannot directly participate in the exact water decision-making, and cannot fully observe the actions of agents, who may act in line with their own preference rather than the governor’s, which leads to moral hazard [30]. The two-stage performance-based mechanism could help governor boost the allocation efficiency and balance the production and environment protection issues. This perspective could also provide a new insight into water resources allocation management and relative decision support for governors.

The main contributions of our paper are two-fold. First, from the governor’s perspective, this paper sets up a two-stage performance-based allocation mechanism to encourage two water users to act according to the governor’s interests. Second, this paper also shows that this mechanism could improve water resources allocation efficiency and balance economic–environmental development.

The rest of this paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents a brief review of the relevant literature, followed by the basic model and key assumptions in Section 3. Section 3 also illustrates the basic information about the incentive model. In Section 4, we present the results analysis and results comparisons. The final section summarizes some conclusions and some discussions.

2. Methods

Our model best suits those water resources governors adopting principal-agent theory in which a governor oversees two water users. We emphasize the interaction between the governor and two competing water users within one cycle of water resource allocation, and the length of a cycle may be as short as a quarter or a year, as long as five years (five-year plan), or one agricultural production period.

In this section, we formally introduce several aspects about the mechanism during this cycle. To begin with, we provide the problem description, the event timetable, and the whole process of this incentive model; then, we put forward the performance-based mechanism. Note that two concepts are essential to our analysis: (i) externalization of the environmental costs, a key step from the governor’s perspective; (ii) the performance-based concept related to production and environment, which is the main constraint for the pre-determined rules.

2.1. Problem Description

Under AS, the governor has to allocate limited water resources to two competing agricultural water users. Before the allocation process, he proposes the pre-determined allocation rules in the first stage and the second stage. The governor, fully committed to this mechanism, will take responsibility for this allocation mechanism. In the first stage, he allocates water resources based on his experience. By the end of the first stage, he allocates the water resources between these users for the second stage by evaluating the users’ previous performances and comparing their previous performances in production and environment aspects, the basic concept of cross-subsidy mechanism. To be specific, if user I performs better than user (3-i), he will receive more water resources in the second stage at the expense of user (3-i), which can be considered as the penalty–reward mechanism. While the governor aims to maximize the utility in production and environment aspects, each user tries to maximize the overall amount of water resources for operation and does not care about environmental protection. To make things worse, the governor could not observe the exact water allocation program between production and environment as it is the private information of the users. Under these situations, this paper constructs a two-stage performance-based allocation mechanism from the governor’s perspective that determines how to improve allocation efficiency, balance economic and environmental development, and encourage the two competing water users to act according to the governor’s interest based on their own performance and their relative performances.

2.2. Events Timeline

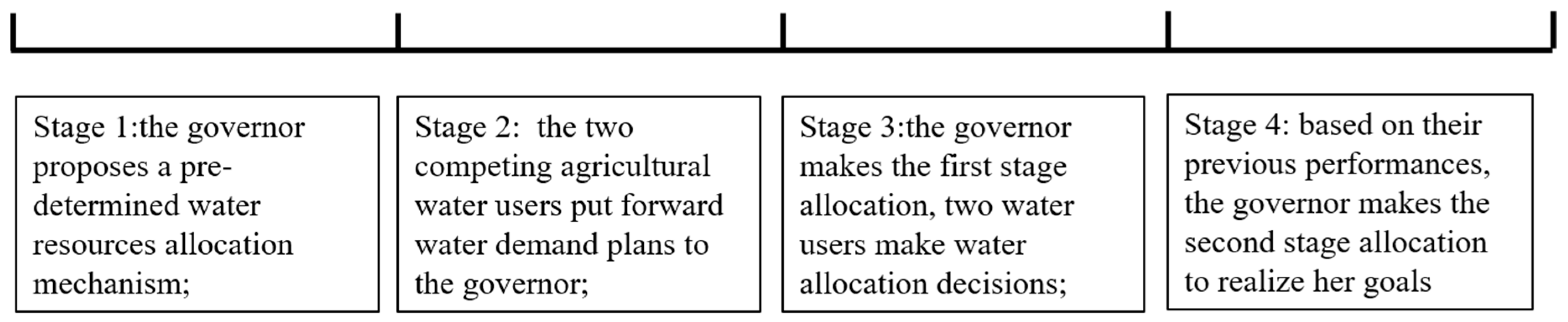

According to the previous analysis, the timeline of the game is as follows (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Timeline of events.

First, the governor proposes the per-determined allocation mechanism to two competing agricultural water users before the allocation process.

Second, the two competing water users put forward water demand plans to the governor according to the production scale in their own region, along with water consumption plans, production targets, and environmental protection targets.

Third, the governor makes the first allocation decisions based on investigation, data collection, and water demand plans.

Last, the governor allocates water resources for the second stage based on the performances, which could realize his primary goals and motivate users to achieve sustainable development and utilization of water resources.

2.3. Basic Assumptions

The assumptions about this performance-based mechanism are as follows: (i) Two competing water departments are both specialists in agricultural and industrial fields, even though they may fail to choose the best strategies sometimes. That is to say, there is no need for the governor to screen out the unskilled one and choose the skilled one. The point is moral hazard issues rather than reverse selection, another research direction. (ii) For the governor, the water resources at disposal do not cover the basic domestic and production water, which means that the basic domestic and production water resources have been satisfied, which is consistent with the reality. (iii) As a rational player, each water user wishes to maximize their own interests, including maximizing the economic interests in the first stage and maximizing the amount of water resources at the second stage. Hence, they both wish to receive more water resources to achieve their current interests, and would like to have a larger share of water resources in the second stage. (iv) From the cost aspect, is increasing and concave, realistically reflecting diseconomy of scale in production and environment protection. (v) All participants are risk-neutral in this paper, with risk-aversion or risk-preference to be studied in the future.

2.4. Basic Information about the Model

2.4.1. Parameters and Function Definition

The basic parameters and notations were defined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters and notations.

2.4.2. Water Resources Allocation Analysis

Suppose that the total amount of water is 1. Let be the share of water resources invested in production at time t for water user j. The cumulative share investment in the production through time T is defined as because the production process requires water resources at t = 0, . Similarly, let be the share of investment in environment protection at time t for water user j. The cumulative share investment in the new product through time T is. .

The governor cannot accurately observe the two users’ resource allocation decisions; instead, she could observe some relative information signals, such as annual reports, production information, and ecological environment factors. However, the two water users’ decisions about and are disturbing for the governor. Even so, the production and environment results will reflect the basic information about their investment information.

As a rational player, each water user wishes to maximize their own interests, including maximizing the economic interests in the first stage and the amount of water resources in the second stage. Hence, they both wish to receive more water resources to achieve their current interests, and they also would like to have a larger share of water resources in the second stage.

2.4.3. Payoff Analysis

Water resources invested into production and environment by each water user could generate corresponding revenues, such as agricultural output and ecological assets output. The revenues generated from agricultural production at time t for the water user j is given by Higher cumulative investment in production results in increased revenues with diminished returns, which means, , and . And the environment program generates a revenue through opportunity cost method, with , and . Meanwhile, it is obvious that the water resources in environment generate further ecological value or environment value beyond the current cycle T. Let be the expected revenue generated by the environment program beyond T, and it also satisfies , and .

2.4.4. Cost Analysis

There are two types of cost during the process of water resources allocation and use. The first one is the cost along with production and environment program from the water users’ perspective, which is denoted by and , including land, personnel, or equipment dedicated to production and environment activities.

The other is the cost for protecting environment from the governor’s perspective, which is denoted by and , where, the is the pollution control costs, is the cost of environment maintain and the ecological environment improvement.

In this paper, we employ the internalization of environmental cost to address the externality issues so as to realize the efficient resources allocation. That is to say, environment issues from the users’ behaviors are referred to as the external effect for the governor, which further influence the governor’s interests. The internalization of environmental cost means adding the cost of protecting environment as a part of the users’ costs and a part of their own and relative performances.

Furthermore, the cost functions () are independent. According to the previous assumption, . and . is increasing and concave, which means, , and . Depending on , is increasing and concave. Meanwhile, depends on . This means that if the users invest more water into environment protection, the governor spends less to maintain the ecological environment. Note that the users must invest some water resources into environment protection according to rules because even though the governor could not observe the exact amount of water resources, he could distinguish whether the users invest water into the environment or not. Besides, the are environmental costs, the internalization of which is the main point for the reallocation rule [29]. It means that the governor wants to transfer the to the users. Under this situation, the users must consider the revenues in both stages, which is consistent with governor’s initial goals.

2.4.5. Information about Performance-Based Mechanism

For the water users, in order to get more water in the second stage, they must improve their own performances and their relative performances, which means that they have to balance water resources in production and water resources in environment, and balance production cost and environment protection cost.

According to the above analysis, the cumulative performance related to water resources allocation at the end of the first period could be written as:. Note that may be positive or negative, which could be a measure of the agent’s environment-conscious performance. To some extent, negative value of implies that the user j performs poorly in environmental protection (a common scenario in practice). A positive value of implies that the agent, who may have a strong awareness of environmental protection, performs well in environmental protection. Except for the absolute value of , the relative value needs to be considered between the two competing users on the basis of the performance-based rule.

We introduce the function as the water users’ performance concerns. To formalize this concept, we define the function as the cost (benefit) of the water user j’ performance at time t. If, the environmental situation will become worse. Conversely, if , the environmental situation will become better. The water user j’s performance is related to the two users’ performances.

2.5. The Objection Function

According to Inalhan et al. [23] and Yang et al. [24], water user j’s behavior can be analyzed by a framework solving the multiple-agent water system problem, in which users maximize their own utility subject to the related constraints. The utility function of the user j can be written as:

In this study, is the user i’s utility function, acts as a local interests factor indicating the selfishness of user j, and is the original objective function. The item is the reward or penalty based on two users’ own performances and their relative performances, which is the key point of the performance-based incentive mechanism based on the competition between two users. For simplicity, this paper sets considering the assumption of rational economic man, who aims to maximize his own interests.

According to the above analysis, the item could be written as:

where is the reward coefficient for , while is the penalty coefficient. Substituting Equation (3) into Equation (2)::

which means, when user j performs better than (3-j), he will receive reward, otherwise, penalty. Reward and penalty are both related to the amount of water resources in the second stage based on their relative performances, which is the so-called penalty-incentive-based system consistent with the governor’s initial goal.

The governor’s utility function is:

which means, from the governor’s perspective, he would like to maximize the subjective utility in economy and environment. The penalty-reward mechanism is cross-subsidy mechanism between the two users.

3. Results Analysis

3.1. Properties of this Objective Function

Based on the utility function, we could get the first-order condition of Equation (4),

and

where means marginal profits of the invested water resources in (i = 1,2; j = 1,2), the Equation (7) contains independent equations and variables .

Besides, the interactions between the two users and between the governor and the water users could be written as:

In Equation (8), user j’s better performance is at the expense of (3-j)’s worse performance, and cross-subsidies mechanism in the AS. This implies that, if user j performs better than user (3-j) from the governor’s perspective, he will get more water resources in the second stage. The performances cover both production and environment aspects. Under this condition, consistent with “rational violation” [28], water user j may invest more water into his preferred actions if the total benefits in the first stage will increase even though he receives less water resources in the second stage based on the penalty–incentive mechanism. Meanwhile, if user j would like to receive more water resources in the second stage, he will choose to act according to the governor’ favorite actions to perform relative better.

In Equation (9), means the administrative cost in the AS, which can also be regard as information costs, decision costs, or enforcement costs [31]. Theorem could be concluded based on Equations (7)–(10):

Theorem 1.

If () is the optimal solution from the governor ‘s perspective, it is the best solution of Equations (7)–(10), where the governor’s original goals will be realized and the two competing users will allocate water resources according with the governor’s interests rather than his expense.satisfies the Equations (7) and (8), and the total benefits from the governor’s perspective is optimal.

This theorem represents the necessary condition for realizing the water allocation sustainability. Under that optimal scheme, on the one hand, the two competing users try their best to maximize their disposable water resources by maximizing their own performances and their relative performances, and on the other hand, the governor will achieve his original goal to improve the allocation efficiency and balance the economic–environmental development.

3.2. Equilibrium Analysis

According to the above analysis, Equations (7)–(10) state an analytical framework that represents the water resources allocation rules under the AS. The existence of the equilibrium solution of Equations (7)–(10) will satisfy the following two conditions: (i) a dominant-strategy equilibrium exists in this mechanism; (ii) in each dominant-strategy equilibrium, E(U*) = max E(U).

For the governor, the optimal incentive mechanism is subject to individual rationality (IR) and incentive compatibility (IC) constraints:

For the governor, the optimal incentive mechanism is subject to individual rationality (IR) and incentive compatibility (IC) constraints:

Note that for the optimal outcome, the governor optimizes and implements a penalty-incentive mechanism so that the two users do not deviate from the governor’s choice of .

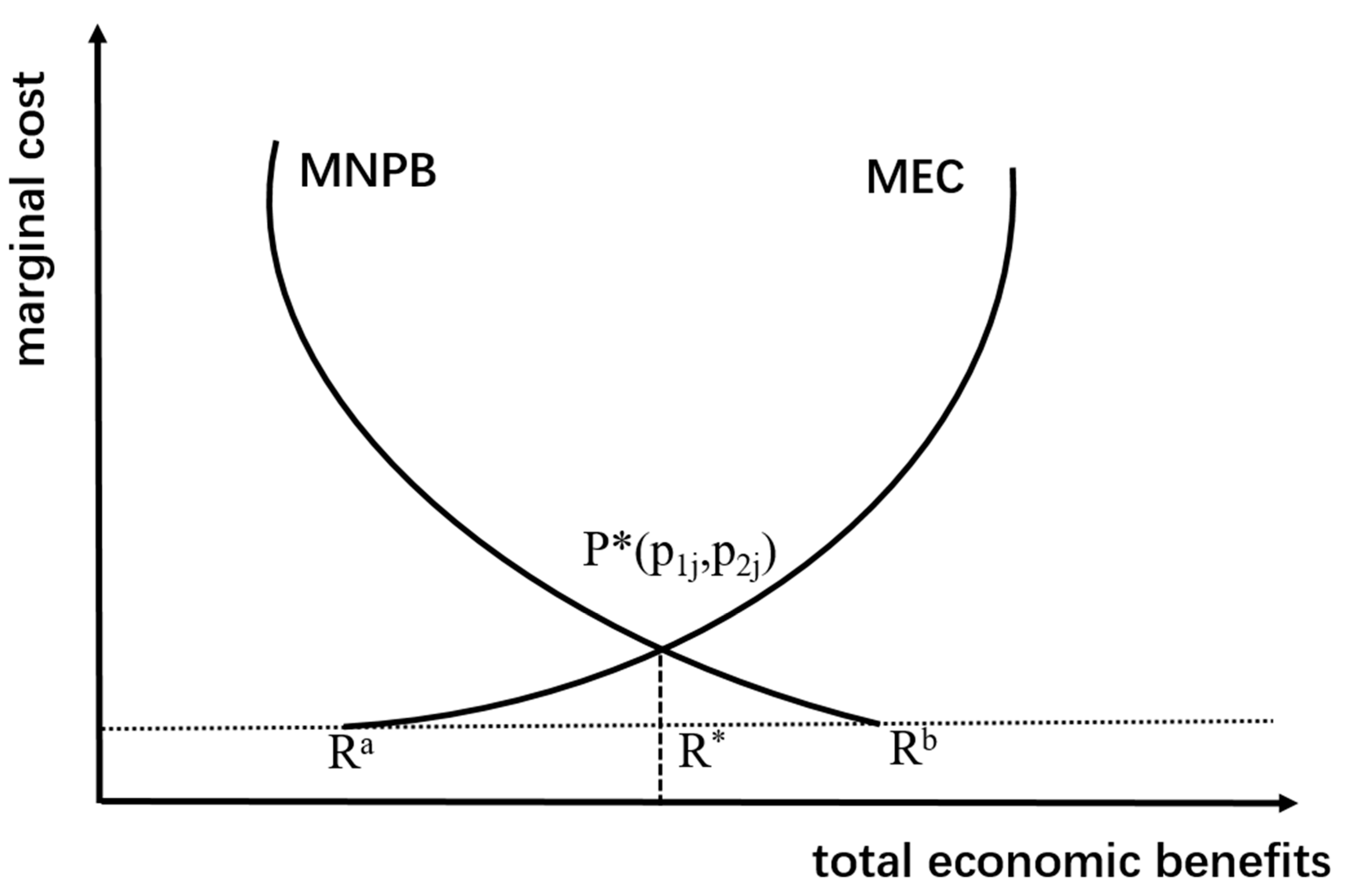

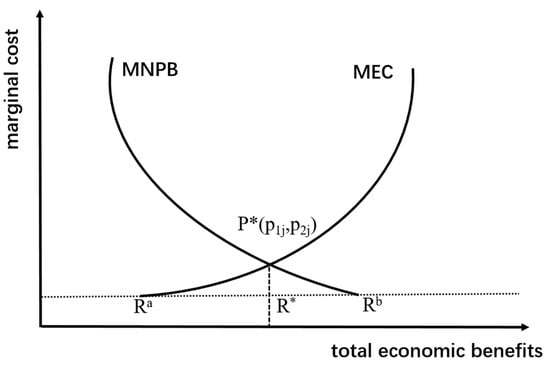

From Equations (7) and (8), users’ marginal benefits equate to marginal costs, which is the best. Throughout the cycle, the marginal benefit consists of the production and environment revenues, and the marginal cost consists of the cost for control environment pollution and for improving the environment. That is to say, for the governor, each user has a threshold point . At this point, the user’ marginal net private benefits (MNPB) equal the marginal external cost (MEC) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The MNPB and the MEC under the optimal outcome situation.

For the governor, the is the equilibrium, where the marginal economic benefit equals the marginal cost, and the corresponding economic point is , where the users’ action is consistent with the governor’s preference. Besides, the environment itself has a certain capacity for self-purification. The point means that the environment has no external environment pollution when economic benefit is . The point means that the user’s marginal benefit is zero. At this point, the users’ revenues are maximized while the governor’s revenue is not.

Note that due to asymmetric information and incomplete information, the perfect ideal scenario could not always be achieved. The optimal allocation decision is achieved by ensuring the users’ incentive compatibility constraint and the signal information (p1j, p2j). Otherwise, the users have no incentive to participate in the allocation game in the next stage.

In this allocation model, not only the revenues of two users are taken into consideration, but also the related costs have been considered. In order to improve the allocation efficiency in agricultural and industrial sectors, the two competing water users need to be aware of the amount of water they invest in corresponding production and environment activities, and the cost thus ensues. This information is essential for the second allocation because the governor can only motivate the two users through water resources flows, which is his only way to restrain the users.

3.3. Water Users’ Behaviors Analysis

The water users’ behaviors are affected by the governor under the AS. Under the performance-based mechanism, the essential step to improve his total benefit is to motivate each user to improve their own performance. During this period, water users choose how much water they invest in production or environment. They also choose to act according to the governor’s interests or to their own interests, which means they will choose to accept a penalty or accept a reward based on their relative performances.

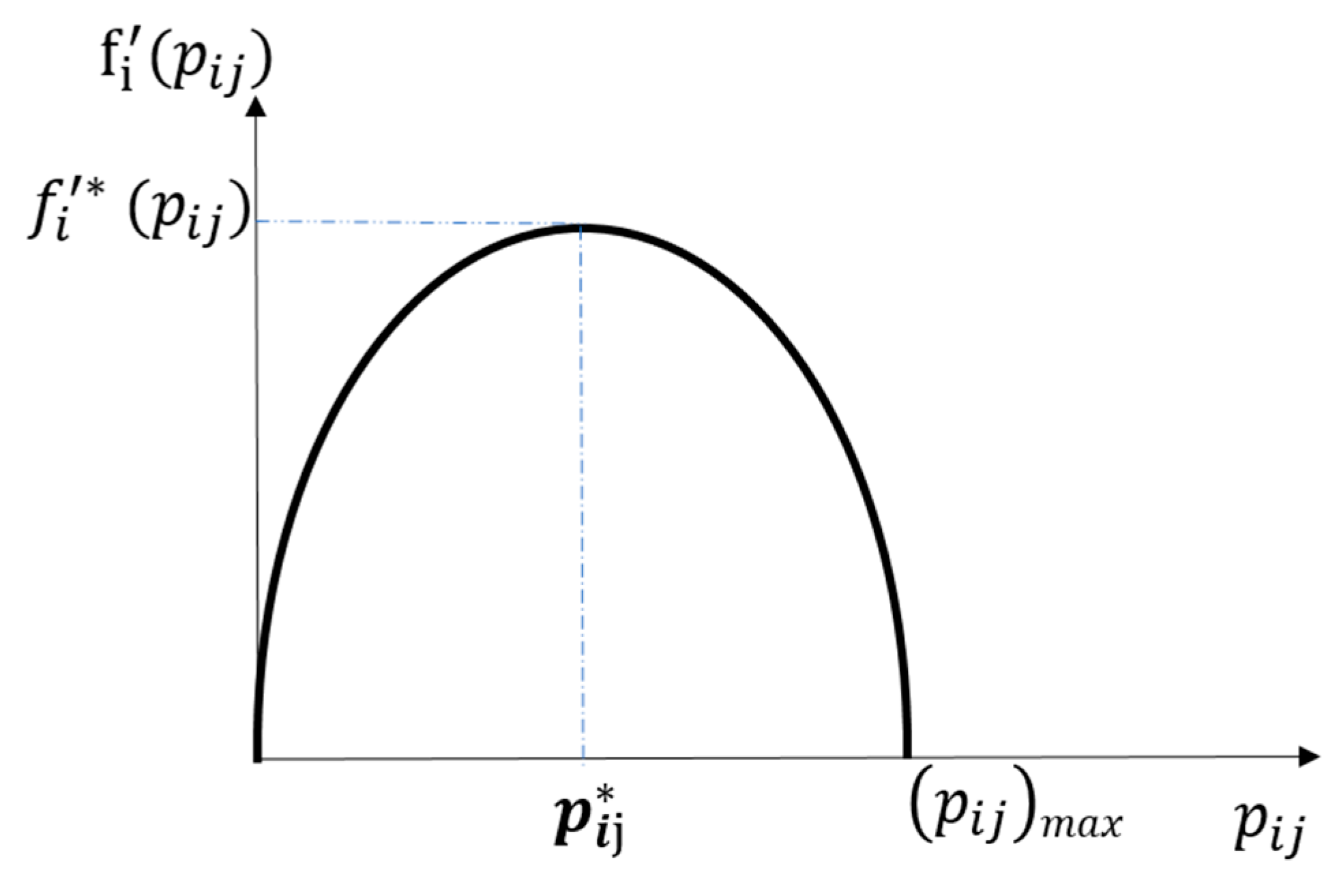

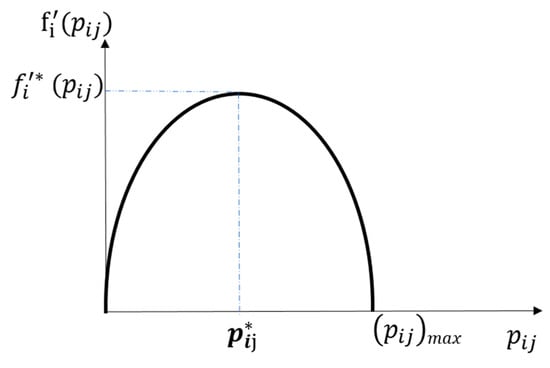

We could further analyze water users’ behavior through a curve description in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Water user i’s behavior analysis.

As shown in Figure 3, from the user i’s perspective, whether investing in production or environment, is their ideal amount of water resources used for these two parts, while is the optimal amount from the governor’s perspective.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

There are three main extensions for future investigation.

First, we can naturally extend this fixed amount of water resources to a variable. In other words, the overall disposable water resources could be more or less in the following step. In case of more disposable water resources, if the hydropower is included, water quantity and water quality will not be reduced. If hydropower is considered, the two water users will also need to consider the secondary distribution of water resources, which makes for another incentive mechanism from the water user j’s point of view. The participants need to balance between making the cake bigger and getting a larger slice of it in the future at the same time, as illustrated by Huck et al. [32]. Under this situation, the three participating parties have a common goal at first, that is, getting more disposable water resources. Then, all the parties try to maximize their own interests. In case of less disposable water resources, due to extreme drought weather, like what happened in Meikong River Basins in 2011, the overall supply water will be less than normal year. Under this situation, the governor will need another incentive mechanism or an emergency mechanism, which will be another interesting research direction.

The second extension is the multi-principal and multi-agent model, including many governors and many water users, existing in transboundary river basins, such as Lancang River, Nu River, Yalu River. There are also competitions between governors whose aims may not be the same. The conflicts of water users involve various agricultural users and industrial users, which will be another complicated model. As this paper only presents a one-principal and two-agent model, we can naturally extend this model to multi-principal or multi-agent (more than two agents). In fact, in addition to the water user j’s allocation, the players could get water resources from various channels, such as water reuse, buying from other players, and so on.

There are also uncertainties of the water allocation process, such as flood or extreme droughts, which affect water allocation substantially. Risk management mechanisms need to address this issue. In fact, the uncertainty of all participants’ behaviors is based on the definition of risk of the water allocation process. It is worth research in the future.

What is left for future research also includes the distribution plan and incentive mechanism under these conditions, and the fact that these water users may have private information, risk-preference, or risk-aversion, which would be left for future research.

4.2. Conclusions

The current paper, based on cross-subsidy mechanism, explores the issue of efficient water resources allocation management between the governor and two competing water users under the AS. The two-stage performance-based allocation mechanism presented in the paper has four novel aspects. First, from the governor’s perspective, we focus on allocation rules covering two stages, including production and environment aspects, which is consistent with sustainability. Even though this two-stage allocation is just a small part of the long-term allocation cycle, it could reflect the real allocation process and reflect the requirement of water resources sustainability under the current social–environmental–economic development. Second, the performance-based incentive mechanism will induce competition between the two users based on the penalty–incentive system to motivate them to act in accordance with the governor’s goals. Users’ payoff depends on their own performances and their relative performances, covering production and environment aspects. Therefore, this mechanism involves not only the interactions between the government and users, but the interactions between two users, which could help the governor balance the economic and environment developments, and balance the short-term development and long-term development. This paper also covers the internalization of the external costs, another innovative aspect in this paper. The internalization of the external costs could help the governor transfer the costs to the users, which could further motivate the two users to act according to the governor’s interests rather than their own interests. At last, these perspectives could also provide a new insight for agricultural water resources allocation management and relative decision support for the governor, such as the sustainable development of water resources, the interactions between the governor and users, competition between users, penalty–reward mechanism, multi-stage multi-agent and multi-objective decision-making, and so on.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and Q.R.; Formal analysis, Q.R. and J.L.; Funding acquisition, Q.R. and J.L.; Investigation, H.Z.; Methodology, H.Z.; Resources, Q.R.; Software, Q.R.; Supervision, H.Z. and J.L.; Validation, H.Z.; Writing—original draft, H.Z.; Writing—review & editing, Q.R. and J.L.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 91647119, 71673210, 71725007).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the funded project for providing material for this research. We would also like to thank editor and reviewers very much for the valuable comments in developing this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wallace, J.S. Increasing agricultural water use efficiency to meet future food production. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2000, 82, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddeland, I.; Heinke, J.; Biemans, H.; Eisner, S.; Flörke, M.; Hanasaki, N.; Konzmann, M.; Ludwig, F.; Masaki, Y.; Masaki, Y.; et al. Global water resources affected by human interventions and climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 3251–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Cai, X.; Wang, Z. Comparing administered and market-based water allocation systems through a consistent agent-based modeling framework. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 123, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, W.; Siqi, L.; Rongrong, L. Evaluating water resource sustainability in Beijing, China: Combining PSR model and matter-element extension method. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Liu, G.; Wang, F.; Ritsema, C.J.; Geissen, V. Domestic water consumption under intermittent and continuous modes of water supply. Water Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelkers, E.H.; Hering, J.G.; Zhu, C. Water: Is there a global crisis? Elements 2011, 7, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, O.P. Fundamental questions about water rights and market reallocation. Water Resour. Res. 2004, 40, W09S08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkkainen, T. Pennies from Heaven: Pricing Irrigation Water; Research Rep. No. 2001; Helsinki Univ. of Technology: Helsinki, Finland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- MWR (Ministry of Water Resources, P.R. China). The 11th Five-Year Plan of National Water Resources Development, the Ministry of Water Resources of the P.R. China; MWR: Beijing, China, 2007; pp. 34–48.

- Sadegh, M.; Mahjouri, N.; Kerachian, R. Optimal Inter-Basin Water Allocation Using Crisp and Fuzzy Shapley Games. Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 24, 2291–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, K. Game theory and water resources. J. Hydrol. 2010, 381, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Fan, Y.; Liu, X.; Park, S.C.; Tang, X. A game-based production operation model for water resource management: An analysis of the South-to-North Water Transfer Project in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1482–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atef, S.S.; Sadeqinazhad, F.; Farjaad, F.; Amatya, D.M. Water conflict management and cooperation between Afghanistan and Pakistan. J. Hydrol. 2019, 570, 875–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Li, J.; Cai, Y.; Tan, Q.; Dai, C. A hybrid game theory and mathematical programming model for solving trans-boundary water conflicts. J. Hydrol. 2019, 570, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanjanian, H.; Abdolabadi, H.; Niksokhan, M.H.; Sarang, A. Influential third party on water right conflict: A Game Theory approach to achieve the desired equilibrium (case study: Ilam dam, Iran). J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 214, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagziel, D.; Lehrer, E. Reward Schemes. Games Econ. Behav. 2018, 107, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.; Webber, M. Incentive-compatible payments for watershed services along the Eastern Route of China’s South-North Water Transfer Project. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 25, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, M.E.; Li, P.; Zhao, D. Water Pollution Progress at Borders: The Role of Changes in China’s Political Promotion Incentives. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2015, 7, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.; Melenhorst, M.; Micheel, I.; Pasini, C.; Fraternali, P.; Rizzoli, A.E. Rizzoli, Integrating behavioral change and gamified incentive modelling for stimulating water saving. Environ. Model. Softw. 2018, 102, 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørum, J.E.; Boesen, M.V.; Jovanovic, Z.; Pedersen, S.M. Farmers’ incentives to save water with new irrigation systems and water taxation—A case study of Serbian potato production. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 98, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luenberger, D.G. Linear and Nonlinear Programming, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sakarya, A.B.A.; Mays, L.W. Optimal operation of waterdistribution pumps considering water quality. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2000, 126, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inalhan, G.; Stipanovic, D.M.; Tomlin, C.J. Decentralized optimization, with application to multiple aircraft coordination. In Proceedings of the 41st IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 10–13 December 2002; pp. 1147–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.-C.E.; Cai, X.; Stipanovic, D.M. A decentralized optimization algorithm for multiagent system-based watershed management. Water Resour. Res. 2009, 45, W08430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadnezhad-Shourkaei, H.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M. Impact of penalty-reward mechanism on the performance of electric distribution systems and regulator budget. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2010, 4, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffont, J.J.; Tirole, J. A Theory of Incentives in Procurement and Regulation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fechete, F.; Nedelcu, A. Performance Management Assessment Model for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza Filho, F.A.; Lall, U.; Porto, R.L.L. Role of price and enforcement in water allocation: Insights from Game Theory. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, W12420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auster, S. Asymmetric awareness and moral hazard. Games Econ. Behav. 2013, 82, 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.; Lei, W.; Sijie, C.; Bo, W. Research on Internalization of Environmental Costs of Economics. IERI Procedia 2012, 2, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carl, D.J. The problem of externality. J. Law Econ. 1979, 21, 141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Huck, S.M.; Hokayem, P.; Chatterjee, D.; Lygeros, J. Stochastic localization of sources using autonomous underwater vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2012 American Control Conference (ACC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 27–29 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).