Abstract

Tourism in inner areas, especially in the mountains, is a complex phenomenon due to the different tourist’s needs and to the specific local features that vary considerably from one destination to another. Consequently, a unique tourism development strategy cannot be defined and adopted anywhere. When considering tourism-based territorial development in mountain areas, it is crucial to take the vision of local stakeholders into consideration. To drive different and/or unexpressed opinions towards shared tools, this study analyses the local stakeholder’s point of view using a mixed method consisting of a Delphi method followed by a Group Nominal Technique. The research was performed in Soana Valley, a small mountain community in the Northwestern Italian Alps. It involved 17 local stakeholders divided into three main groups—local administrators (n = 3), hospitality operators (9) and retailers (5). Results show how operators converge on three common aspects—local food product offering, territorial promotion and collaboration among operators, on which the community should focus to build a territorial integrated tourism offering.

1. Introduction

Mountains are very popular tourism destinations in the world, second only to coast and island resorts [1], accounting for about 15% of worldwide tourism and with an economic impact between 70 and 90 billion U.S. Dollars per year [2]. Moreover, mountains are all over the world, covering 24% of the land surface [3]. Their characteristics vary widely based on climate and vegetation as well as animal species and human activities. Europe alone, for instance, accounts for seven mountain chains [1]—the most important is probably the Alps—which exist in different countries with peculiarities in terms of biodiversity, natural constraints and opportunities as well as culture, traditions and economic activities.

When considering tourism in mountain areas, therefore, the complexity of this sector has to be taken into account—mountain tourism largely depends on specific features of the area and involves a huge range of activities as influenced by environment and cultural heritage. Tourists have different need, for instance relaxation, sports, leisure, wellness [4,5], and a mountain destination may not always be able to provide all the desired responses [4].

The ability of a mountain destination to cope with tourists’ requests, thus, depends on several factors—natural and geographical constraints, local policy and legislation, cultural heritage and local entrepreneurship. Consequently, mountain tourism varies among destinations, sometimes specialising in a single characteristic or activity—mountaineering in the Himalaya range, skiing in the Alps and so forth.

Moreover, mountain tourism has recently become vulnerable to climate changes, which affects seasonal tourism. Indeed, over the last two decades, snow-cover duration changes impacted on winter tourism calling for new adaptation strategies that involved inhabitants, institutions, entrepreneurs and tourists [6,7,8,9]. Some authors suggested activities to galvanise winter tourism and/or support the summer season on the basis of economic sustainability, for example, considering the snowmaking issues [10,11,12] or defining adaptation strategy plans [13,14,15]. Some others underlined that eco-tourism and natural heritage in mountain areas can be considered important alternatives to incoming sources and stimulate new opportunities [16,17].

When taking into account the Alps, tourism is an outstanding phenomenon—with about 120 million tourists per year [18], the Alps are one of the most visited mountain ranges in the world.

Arrivals and presences in the Alps, however, vary from destination to destination; in some alpine valleys, tourism is so developed that is starting to create concerns around its environmental and social implications due to over tourism [19,20]. On the other hand, some alpine valleys, which do not have renewed hallmarks, are not popular even if the local context would be able to provide guests with an interesting tourist offer. This is the case for Soana Valley, an inner mountain region in Piedmont Alps (Northwest of Italy), located 60 km from Torino—its state capital—and within the border of Gran Paradiso National Park (GPNP)—the first ever-established Italian national park—that aims at relying on the natural and cultural heritage for local development. In the Valley there are three municipalities—Ingria, Ronco Canavese and Valprato Soana—for a total population of about 455 inhabitants, living on a very vast area (the overall surface is about 182,870 km2). Ranging from about 600 m to 3000 m a.s.l., the territory is completely mountainous.

Being a small community—as already mentioned—the Valley is trying to define its offering in order to attract new forms of tourism, based on its two main economic sectors—agriculture and tourism. The former basically relies on livestock breeding, which accounts for 400 bovine heads and 500 small ruminants exploiting pastures. Furthermore, even if the tourism sector in this area has been showing dynamism in the last few years, some concerns have been raised due to the attractiveness of the Valley. In order to better identify the Valley’s tourism offer, the stakeholders’ opinion and vision are the basis on which a tourism strategy can take shape and evolve. This is the reason why the first step of a tourism plan should assess the stakeholders’ opinions, to be discussed among all the local operators and to identify a common and shared tourism strategy. Even if some former studies in the area focused on the historical or natural aspects [21,22], tourism being a relatively new phenomenon for the local community, research has never considered the local actors’ point of view. This study tries to fill that gap.

This paper, therefore, presents the results gathered with a mixed approach, which combines the Delphi method with the Nominal Group Technique for stimulating a shared tourism strategy in the area, which should improve its economic development.

The analysis here presented is organized into 6 sections: Section 2 presents the conceptual framework, deals with mountain tourism and sustainable tourism with a specific focus on protected areas; Section 3 contains the case study description and the methodology, whereas in Section 4 results are shown and discussed. Finally, the Conclusions present both the strong points and limitations of the study and suggest new possible avenues of research.

2. Literature Review

The competitiveness of tourist destinations and, more generally, the success of a devoted area passes through the identification of specific discriminating factors determined by a series of variables. Among them, some authors point out that the distinctive features of the study area are the most important [23,24,25]. In this context, elements such as the quality of food products and their links with the production area are capable of characterizing a territory as a tourist destination [26,27,28]. Indeed, food and wine heritage can be considered an essential resource to create appeal and support the tourism offering. Several authors indicate local food as an element of tourist attraction either in terms of consumption [29,30], heritage and territorial characterization [31,32,33], and, in some cases, it is identified as a travel motivation [34] in mountain areas [35]. Food and wine are also elements of attraction for specific population classes, significant from the point of view of consumption levels, such as the Millennials [29,34,35].

As aforementioned, the territory and its promotion can be enhanced through the identification of distinctive characters, such as local products, but at the same time, they should be made easily recognizable. The implementation and use of territorial trademarks can lead to an easier recognition of the considered area with the improvement of tourism promotion and territorial visibility and with the increase of the attractiveness of capitals to invest in local productive activities [24,26,36,37,38].

In this sense, the presence of a protected area, characterized by a strong recognition, can be of value for territorial promotion. In many cases, the relationship between protected areas and tourism destinations is mutual. Tourism is an important resource for natural parks because the modern mountain tourist tends to positively assess landscapes, symbiotic nature-agricultural activities, nature-based life style and natural heritage [39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. The first studies linking protected areas and mountains focused on ecosystem protection [46]. Dixon and Sherman [47] enriched the relationship with the economic repercussions of tourism for the protected areas, which have great tourism potential because of their natural and cultural heritage. For these reasons, these areas have been opened to tourism worldwide [48]. Two interesting contributions by Nepal [49,50] include one on the Himalaya Mountains, one of the most visited mountain areas in the world, which highlighted that tourism, especially ecological tourism, can generate development in mountain areas, but it must be carefully governed [51,52,53,54]. Ioan [55] stressed that “ignoring the local mountaineering culture built up during the century old exploration could alter the relation with mountaineers, although these stakeholders are most likely to volunteer for various actions needed in conservation or monitoring.”

A current topic in the scientific debate is the role of sustainability in the choice of tourist destinations [56]. Weaver [57,58] realized a management model to assess the sustainability of tourist destinations. Duglio and Letey [59] applied this model at the Gran Paradiso National Park (GPNP), in the North West of Italy, and concluded that “a protected area does not necessarily contrast the tourism industry but instead may boost local development by driving it within the borders of the sustainable development, switching from the area’s only preservation function to a flywheel for the local communities.” Some research highlighted the touristic importance of protected areas such as UNESCO sites, where, however, a very large number of visitors could make tourism unsustainable [60,61].

Hammer and Siegrist [62] have identified environmental protection as the most relevant factor for the development of naturalistic tourism in marginal areas, which however must be supported by effective policies by local stakeholders. Knowledge of the local stakeholders’ opinion and needs is essential to develop effective territorial development policies in protected areas. Some scholars agreed that stakeholders who have economic activities such as agriculture must play an active role in the local economic development [63,64,65,66]. Indeed, several studies reported that the success of an area as a tourism destination could pass through an improved management of the agricultural land using development tools, such as a Land Consolidation Association [67,68,69].

Since tourism is becoming increasingly important among the activities in the parks, the knowledge of the opinion of both tour operators and protected area visitors is needed [70,71,72]. Moreover, local operators should collect the suggestions of the residents living in the protected area, who could offer useful elements for local development actions [73].

Taking the role of protected areas, agriculture, tour operators, visitors, and residents into consideration would boost the development of eco-friendly tourism, going in the directions of a new equilibrium with the Earth’s environment, which the tourist sector is looking for [10,74,75,76,77] and answering tourists’ requests for sustainable activities [78,79,80,81].

This attitude is also evident in the mountain areas where landscapes [39,40,41], climate change [82], development of the eco-tourism [42,43] and natural heritage [44] are taken into account and can be embodied in a new dimension of the tourism concept. Indeed, the mountain tourism industry needs some transformations.

Finally, local communities and local stakeholders that is, public and private operators, are very important elements for enhancing the territorial area and improving the knowledge and promotion of the territory. As already mentioned, several studies showed that the involvement of local communities in tourism topics is a useful strategy to improve service and hospitality such as, for example, guaranteeing participation equity and recognition equity in protected areas [83], managing natural and cultural heritage [84,85] and improving the value of attractions [86].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Area of Investigation

The study was carried out in Soana Valley, an alpine inner area in the northwestern Italian Alps, Piedmont Region, located about 60 km from the main town of Torino. Soana Valley has three municipalities—Ingria, Ronco Canavese and Valprato Soana—with an overall surface of about 182,870 km2 and a population of 455 inhabitants, with a density of 2.49 in/km2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The area of investigation.

From a geomorphological point of view, the valley is North–South oriented and develops along the Soana stream at an altitude ranging from about 3,000 m to 600 m a.s.l.

The valley is part of Gran Paradiso National Park (GPNP), which has allowed the valley to maintain a high level of biodiversity according to its institutional scope. The park encroaches on two out of the three municipalities (Ronco Canavese and Valprato Soana), for about two thirds of their territories (71% and 69% respectively).

Socio-economic indicators show this area has a medium–high level of marginality. Its index of marginality ranges between –0.384 and –0.556 [87,88], among the lowest in the Piedmont Region. Such an index, elaborated by IRES (Istituto di Ricerche Economico Sociali del Piemonte—Piedmont Institute for economic and social researches), took into consideration four main dimensions, each of them analysed thanks to devoted indicators—demography (3 indicators), income (3 indicators), level of services (3 indicators) and economic fabric (2 indicators) for a total of 11 indicators.

Table 1 contains the demographic trend of the three municipalities, as expressed by “Old-age Index” and “Structural dependency index.” The first index represents the ratio between old population—more than 65 years old—and young population—between 0 and 14 years old—whereas the second is the ratio between the not active population—more than 65 years old and between 0 and 14 years old— and the active population—between 15 and 64 years old, in percentage.

Table 1.

Demography indexes.

These data clearly show how the population structure may result in severe limitations for development, as most of the population is old and about half are not of working age. As a consequence, each action proposed by local administrators should attract, or at least maintain, the human capital represented by the young generations.

As far as the economic sector is concerned, Table 2 reports the number of farms and the Utilized Agricultural Area (UAA) from the last census of agriculture [89]. The UAA is very limited: 684 ha, corresponding to 3.7% of overall surface, of which 99% is represented by permanent meadows and pastures. Occurring over an area of just 1.2 hectares, crops are a residual land use, which nowadays has little or no economic relevance. Conversely, livestock breeding is still an important agricultural activity; approximately 400 bovine heads and 500 small ruminants graze pastures at the highest altitudes during summer.

Table 2.

Number of farms and Utilized Agricultural Area (UAA).

As far as the tourism sector is concerned, the most recent data report two hotels (40 beds), a guesthouse (8 beds), a Mountain bivouac for the Great Crossing of the Alps (6 beds) and a Mountain hut (restaurant of 80 places and bivouac of 8 beds). Tourism trends during the last few years are reported in Table 3. Tourist presence has constantly increased in the last five years, passing from 12 to 1204, but tourist arrivals are fluctuating, especially when considering foreign tourists. Furthermore, the analysis of Average Length of Stay (ALS) shows the area is not able to attract tourists for more than one night. The data on the tourism sector show lights and shadows—on the one hand, tourism in the area exhibits some dynamism in terms of both the increasing number of accommodation facilities and tourist presence. On the other hand, the tourism offering is not able to keep tourists in the area, as showed by the low values of the ALS indicator. Starting from the consideration that, due to the presence of Gran Paradiso National Park, which represents a hallmark for this territory [59], tourism offering may rely on natural capital, the data justify the need to use stakeholders’ viewpoints on the strengths and weaknesses of the Valley tourism, offering a base for speculating a development strategy.

Table 3.

Tourists’ arrivals and presences.

3.2. Methodology

This study uses the Delphi method and the Nominal Group Technique to gather the data needed to improve the economic and social development of Soana Valley in terms of agriculture and tourism.

The Delphi method has been used in several sectors, for example, agriculture [90,91], energy [92], tourism [93,94,95,96] and hospitality [97,98,99]. Previous studies proved that the Delphi method is more effective than other methods [100,101,102] in reaching goals and generating solutions.

Since stakeholders are often not willing to share their own ideas with others, the Delphi method was a useful tool to bypass their diffidence and collect stakeholders’ needs. In this context, the Delphi technique was used to identify assets and weaknesses of the territory, and identify practical solutions to improve the services.

Moreover, the Delphi method was used alone [90,98,99,103,104,105,106] or with other quantitative and/or qualitative investigative instruments, for example, Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) [91,94,95,107], Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) [94,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114], cluster analysis [92,115,116] or Nominal Group Technique (NGT) [117,118,119,120,121]. NGT aims at building consensus among different stakeholders belonging to a group [114] and it is useful when difficulties in identifying problems and their solution within a community or group occur [122]. It allows to overcome group decision-making related issues [123] and stimulates the participation of all interested subjects, including the inhibited ones [122]. This technique involves several steps to reach the consensus—to bring out ideas to be shared later, the first phase is dedicated to individual reflection on topics identified by a facilitator; the second phase involves sharing ideas and the identification of priorities for the collective good [122]. Therefore, NGT allows individual and group working at two subsequent stages, which conclude with a list of priorities [124,125]. Even if there are some examples of implementation of the NGT tool in the tourism sector [126,127,128], to the authors’ knowledge a lack in its application when considering the inner mountain area still exists.

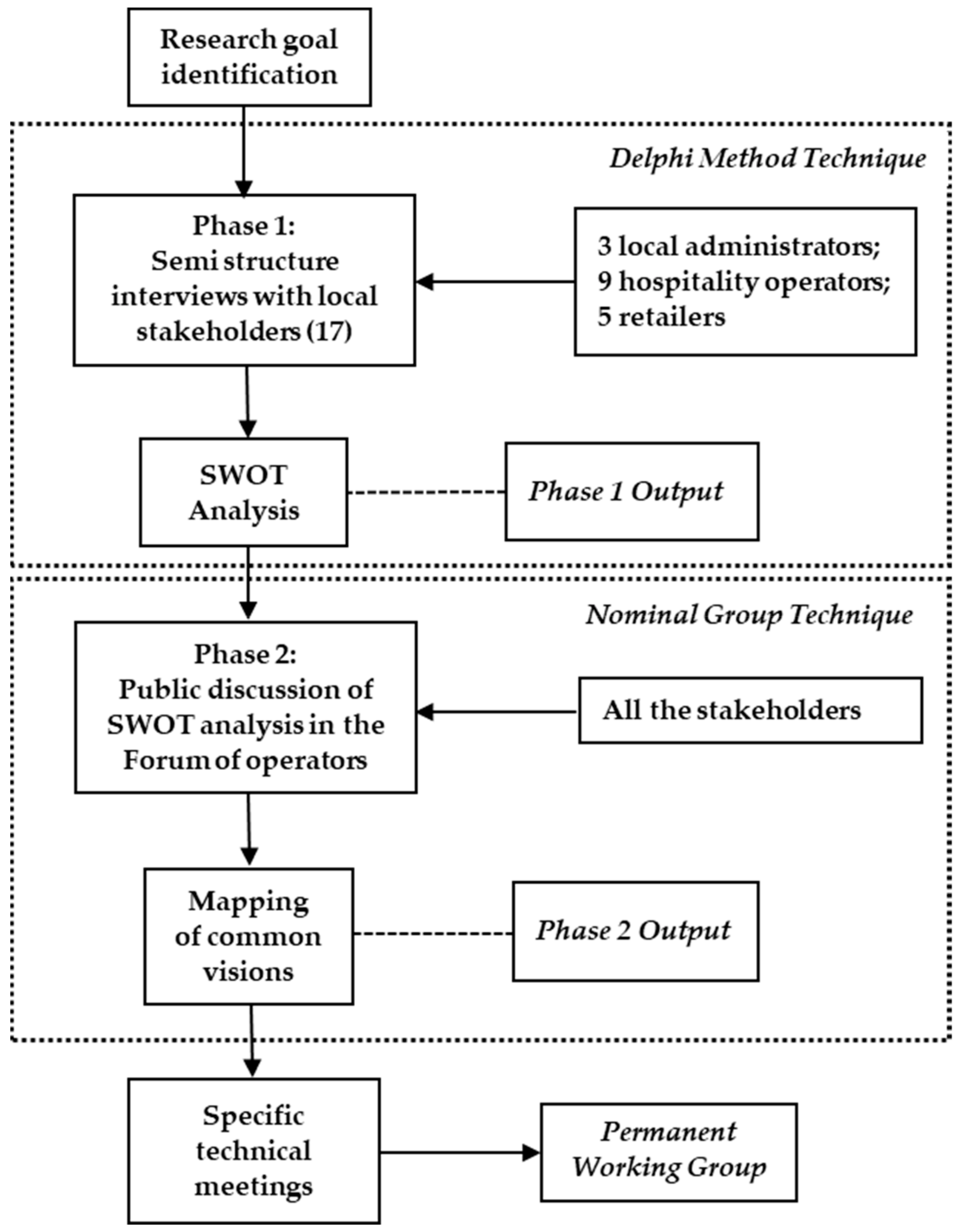

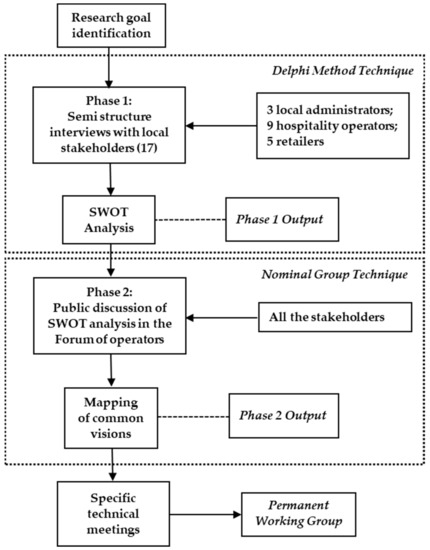

Our study was structured in two stages—one-round Delphi survey, to collect information from different stakeholders from the valley on its productive activities, followed by one-round with the Nominal Group Technique, to consolidate the stakeholders’ ideas, identify the strategy to improve the touristic appeal and classify the main tools to implement such strategies (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Research phases and methodology adopted in the study.

This hybrid method was chosen to involve all the stakeholders gaining their confidence with the two-step analysis (individual interview by Delphi and two-phase trail from ideas to priorities by NGT). This methodology was proposed by a panel of experts with various backgrounds [129], selected on the basis of their knowledge and closeness to the topic of the study [130] to investigate the main objectives and share consensus on the activities to implement [118,121]. Different kinds of closeness were considered, that is, subjective, objective and compulsory, where the first class identifies individuals that have deep experiential knowledge (e.g., Soana Valley stakeholders), the second identifies the researchers on the topic and the third the public operators [131]. Moreover, the competency requirements [132] were considered, namely experience and knowledge on the topics of this study, time availability and interest to participate, communication skills and efficiency [131]. Local public administrators, hospitality managers, restaurateurs, business owners and retailers operating in the three municipalities of the valley and other operators made up the expert panel.

The first step of the Delphi was carried out with an individual semi-structured interview. To collect information, detect discrepancies and assess any structural weaknesses, a first version of the questionnaire was drawn and tested on a sample of interviewees (five) [31,133,134]. A final version was produced subsequently, which was divided into three parts—the first to gather data on strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats; the second related to tourism; the third related to stakeholders and their role in improving the appeal of the territory.

A total of 17 stakeholders replied to the semi-structured interview [135] during summer 2017 and winter 2017–2018. The interviews lasted from 60 to 150 minutes. The interviews were recorded and the interviewers noted the main topics. The collected data and information were polled and equally divided up between the authors, who analysed them separately so as not to influence each other [136]. The results of the analysis were then compared, and the main achievements identified.

The second step with NGT was implemented on the basis of the results obtained at the first Delphi stage. Since our study was carried out from the very beginning with the local community, that is, involving all the tourism stakeholders, the phenomenon known as “panel attrition” [96] was limited to one stakeholder between the Delphi and the NGT step. NGT started with some indications from Delphi that the facilitator proposed to stakeholders. The stakeholders worked individually to output some reflections on the topics and wrote them on some sticky notes. Then, the facilitator collected all reflections and shared them with the group to stimulate the debate and identify priorities. The stakeholders participated to NGT summit in March 2018. Each stakeholder contributed to generating ideas and reflections and identified the main priorities. The meeting lasted three hours.

To the authors’ knowledge, the presented hybrid method has never been applied for analyses in inner mountain areas.

4. Results

4.1. Phase 1: Delphi Method

Seventeen interviews were carried out and were split into three groups—Hospitality operators (9), Local administrators (3) and Retailers (5). The answers provided by the local stakeholders were ascribable to 26 macro-topics (Table 4), each attributed to four categories: Strengths, Weakness, Opportunities and Threats. Sometimes macro-topics were placed in two or more categories deepening on the point of view of the stakeholders and some topics were sometimes widely shared among different groups.

Table 4.

Stakeholders’ responses categorized in Strengths, Weakness, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT).

Among the Strength aspects, the natural environment (water quality and availability, high flora and fauna biodiversity) was relevant for all the groups. Local Administrators pointed out the link between this aspect and the presence of the protected area with its role in nature conservation [59]. It is worth noting that among the “environmental” positive aspects they also included the local food products, essentially dairy productions and liqueurs. The strong cultural heritage of local population was perceived as relevant in generating the link with the territory and as a main factor in counteracting depopulation in the area [137].

When analysing Weaknesses, all the three groups highlighted the lack of accommodation facilities, that is, reduced offering of beds, as well as the obsolescence of some of them. Furthermore, the seasonality of tourism, with its presence concentrated mainly in the summer season, was considered an issue. All groups agreed that the valley seems to be little known not only by foreign tourists, but also by domestic ones, even at a regional level. Some concerns related to the lack of basic services (medical, banking, postal), infrastructures (electricity supply unreliable) and accessibility were also stressed, even if the same operators realize these problems are common to all the inner mountain areas.

The valley offers many Opportunities for developing a sustainable tourism offering in the area. All operators agreed that the presence of GPNP, its structures and its network can act as a flywheel for promoting the area. Among the other opportunities, operators insisted on holiday houses, nowadays little used by the owners, that might be converted into a new form of hospitality [138]. Similarly, an organized and well-directed promotion of territory, which is undeveloped at present, represented an often-shared opinion.

As far as the Threats are concerned, over tourism due to excessive tourism development was considered as the main concern, being responsible for the depletion of the abovementioned environmental and cultural heritage.

The output of the first stage was a categorization of macro themes in the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) matrix of Figure 3.

Figure 3.

SWOT Matrix.

4.2. Phase 2: Nominal Group Technique

At the second stage, the research team drove the stakeholders in their reflections, using NGT. Based on the Delphi results, the facilitators proposed three nominal questions, asking the local stakeholders to respond individually and anonymously by writing their reflections on sticky notes. According to the adopted technique, first the facilitator attributed answers to the corresponding question. Then, each response was analysed and the debate stimulated by interacting with stakeholders. Priorities, strategies and tools identified at this stage are reported in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 clustered into some main categories.

Table 5.

Priorities.

Table 6.

Strategies.

Table 7.

Tools.

There are several priorities to be pursued for the sustainable development of the valley, and tourism plays the essential role (Table 5). Some aspects concerning the local community are also important, as collaboration and dialogue among local actors.

Thanks to the second question, to identify strategies participants were asked to reflect on the creation of relations between different operators, in particular between three categories—restaurateurs, retailers and farmers. Together with the need for better promotion and valorisation of the local heritage, the rediscovery and diversification of local food productions emerged as key factors (Table 6).

Different tools were identified by the participants in order to achieve priority goals and implement the strategies (Table 7), of which most relate to the promotion of productions.

5. Discussion

With a mixed method approach applied to all the actors in the area, we better understood the stakeholders’ opinions on current local development. The adoption of NGT subsequently allowed the re-elaboration of the information for identifying the priorities and the tools useful for developing tourism in the valley.

Although stakeholders all belong to the same area, discussions involving all actors are infrequent; the management of conflicts due, for instance, to the concomitance of many events in a short period would be avoided by increasing the collaboration among local actors. Moreover, local networking would improve the promotion of available resources. Being recognized by all the stakeholders the essential role of all territorial operators for the development of the area, the lack of dialogue and coordination amongst local operators was perceived as the main barrier to successful tourism and local development.

All the stakeholders’ groups (Local Administrators, Retailers and Hospitality operators) recognized the environmental heritage, especially the uncontaminated nature with its flora and fauna, as the main important aspect on which a tourism strategy should rely. This asset derives from the presence of a protected area, the national park, which guaranteed the preservation of the landscape. For this reason, the protected area is recognized as an opportunity for future development in a tourism perspective. According to Gios et al. [139], natural resources are central in tourist development of mountain areas and protected areas specifically have an important role in terms of tourism attractions [46,59]. The conservation of the landscape, as well as its management, was considered of remarkable importance. In order to improve it, stakeholders requested the support to create a Land Consolidation Association and restore the “unused” land. This institute, created by a regional regulation of Piedmont Region in 2016, is a suitable tool for the restoration, the enhancement and the protection of environment and landscape and may contrasts land fragmentation and natural hazards (for instance, fires) by implementing a cooperative management of agri-pastoral land.

With regard to tourism organization, stakeholders focused their attention on the lack of accommodation structures in the Valley and their inadequacy. Soana Valley was affected by remarkable emigration fluxes in the past. However, the next generations returned to the valley as tourists during holidays and in the summer period. This meant that a number of second homes were built. Nowadays, these homes, partly unused or underused, can be a valid opportunity to be taken into consideration and to enlarge the offering of the area. New forms of hospitality, like house sharing, are an interesting perspective, in a specific context such as the one of the valley, characterised by a high number of second homes [59] and the presence of several young inhabitants, more likely to use house sharing platforms to convert their properties into hospitality facilities. Better real estate management could develop tourism and consequently improve the creation of opportunities for the local community. This would also result in a reduction of the risk of mass tourism, which local stakeholders perceive as a limit to the appreciation of the specificities of the territory, and a risk of depleting the environment, local tradition and culture.

Moreover, the development of a valley, in particular for touristic purposes, passes through its promotion; it was acknowledged that the area is little known and targeted promotion actions could contribute to its development. Hence, as main priorities, the local stakeholders identified a targeted promotion of the territory, dedicated to tourists who seek nature and local values (traditional productions, history and culture). As highlighted by several authors, the agricultural heritage, of which the valley is rich, is an important resource to construct territorial appeal and to support tourism offering [30,31,32]. A way for the promotion of the area could be an enhanced exposure of local agricultural products, which are available but not yet promoted. Several livestock farms produce dairy products (cheese, butter) and meat during summer, whose value is not sufficiently recognized even on the local market. The local products, mainly cheese, require some sort of quality “standardization,” as highlighted by the operators themselves, but also could be more easily identified and recognized. A common brand identifying products and certifying their quality on the basis of a strong link to the territory could boost tourism in the area [26,38].

In conclusion, mountain institutions, mountain stakeholders and research centres should analyse the tourist market demand and its changes and identify the strategic tools to meet tourist and local operators’ needs. These tools have to comply with the needs of the environment, reinforce the cultural and social sustainability and improve the local proactivity [140,141,142]. Moreover, it is appropriate to focus on the promotion of the valley, with an offering that takes into account tourists’ demands, particularly the ones of future generations [34,35], but that enhances also the territory and local productions, for example, through a local brand implementation.

6. Conclusions

Because of its nature, mountain tourism is a complex phenomenon that does not allow the identification and implementation of standard strategies that can be adopted everywhere. Moreover, when considering small mountain areas, as the area here studied, not only should the stakeholders’ opinions represent the starting point for shaping a tourism strategy, but it is also important to devise with locals a shared vision and related tools.

The present contribution, thanks to the adoption of a mixed method approach for involving the local community in a shared development strategy, shows how local stakeholders are willing to contribute to the debate, offering their viewpoints. Regardless of the group (tourism operators, retailers and local administrators), all the local stakeholders’ converge on some common tools and strategies for boosting the local economy with a particular focus on local food products and territorial promotion, stressing in the meantime the possible interconnections with the agricultural sector.

Taking into account the tourism dimension of the studied area as a flywheel for the economic development, this contribution represents a first attempt to analyse inner mountain area related issues with a mixed method combining Delphi and NGT. To our knowledge, in fact, no other studies have been carried out in this area involving the local community directly and taking its viewpoint into consideration, nor has the proposed methodology been used with a specific focus on inner mountain areas.

As most research projects, however, this contribution has some limitations that may represent in the mean time possible new avenues of research. A first limitation was the area of investigation itself; Soana Valley is a small mountain community. Its size allowed a high level of stakeholder involvement—3 out of 3 municipalities, 5 out of 6 retailers and 9 out of 11 hospitality sector operators—and the methodologies are replicable in larger areas, but some of the results and consideration of the discussion session could be biased by the small sample size. A second limitation, which is in the meantime a possible new avenue of research, was the citizens’ engagement for having an opinion on what they expect from tourists [143]. In the current study, in fact, and in consideration of its size, we considered the point of view of local administrators as representative of citizens’ viewpoint. Nevertheless, future research may directly involve citizens in the process, as individuals or through local associations, by proposing specific technical meetings and permanent working groups.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed fully and equally to this work.

Funding

This study has been carried out thanks to participation in the Research Project, EMERITUS -Eco-ManagemEnt of agRI-Tourism in moUntain areaS, with the economic support of Compagnia di San Paolo di Torino.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all Soana Valley operators for their collaboration and their suggestions. Heartfelt thanks are due to the local administrators of the Municipalities of Ingria, Ronco Canavese and Valprato Soana for their support during the analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations Environment Programme. Tourism and Mountains: A Practical Guide to Managing the Environmental and Social Impacts of Mountain Tours; UNEP: Paris, France; Conservation International: Arlington, VA, USA; Tour Operators’ Initiative: Madrid, Spain, 2007; ISBN 978-92-807-2831-6. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Program. Tourism in Mountain Regions: Hopes, Fears and Realities; Department of Geography and Environment, University of Geneva: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; ISBN 978-2-88903-027-9. [Google Scholar]

- Richins, H.; Johnsen, S.; Hull, J.S. 1 Overview of Mountain Tourism: Substantive Nature, Historical Context, Areas of Focus. In Mountain Tourism: Experiences, Communities, Environments and Sustainable Futures; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2016; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Duglio, S.; Beltramo, R. Mountain tourism in Europe. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 22, 129. [Google Scholar]

- Cater, C. Management perspectives of mountaineering tourism. In Mountaineering Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 339–353. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J.; Tervo, K. Perceptions and adaptation strategies of the tourism industry to climate change: The case of Finnish nature-based tourism entrepreneurs. IJISD 2006, 1, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauch, R.L.; Raymond, C.L.; Rochefort, R.M.; Hamlet, A.F.; Lauver, C. Adapting transportation to climate change on federal lands in Washington State, U.S.A. Clim. Chang. 2015, 130, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocolas, N.; Walters, G.; Ruhanen, L. Behavioural adaptation to climate change among winter alpine tourists: An analysis of tourist motivations and leisure substitutability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 846–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, I. Climate Change Impacts on Ecosystem Services in High Mountain Areas: A Literature Review. MRED 2017, 37, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, C.; Pickering, C.M. Perceptions of climate change impacts, adaptation and limits to adaption in the Australian Alps: The ski-tourism industry and key stakeholders. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rixen, C.; Teich, M.; Lardelli, C.; Gallati, D.; Pohl, M.; Pütz, M.; Bebi, P. Winter Tourism and Climate Change in the Alps: An Assessment of Resource Consumption, Snow Reliability, and Future Snowmaking Potential. MRED 2011, 31, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pütz, M.; Gallati, D.; Kytzia, S.; Elsasser, H.; Lardelli, C.; Teich, M.; Waltert, F.; Rixen, C. Winter Tourism, Climate Change, and Snowmaking in the Swiss Alps: Tourists’ Attitudes and Regional Economic Impacts. MRED 2011, 31, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.M.; Castley, J.G.; Burtt, M. Skiing Less Often in a Warmer World: Attitudes of Tourists to Climate Change in an Australian Ski Resort. Geogr. Res. 2010, 48, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervo-Kankare, K.; Hall, C.M.; Saarinen, J. Christmas Tourists’ Perceptions to Climate Change in Rovaniemi, Finland. Tour. Geogr. 2013, 15, 292–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornier, R.; Mauri, C. Overview: Tourism sustainability in the Alpine region: The major trends and challenges. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basora Roca, X.; Romero-Lengua, J.; Sabatéi Rotés, X.; Segues Marco, M. The forest as an eco-touristic resource in mountain areas: The case of Mig Pallars and the Alt Pirineu Natural Park (Catalonia, Spain). Ager. Revista Estudios Sobre Despoblación Desarrollo Rurales 2010, 9, 31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, M.C.; Martín, M.B.G.; López, X.A.A. La apuesta por el patrimonio histórico-artístico en el turismo de montaña. El caso del Pirineo Catalán. Scripta Nova. Rev. Electrón. Geogr. Ciencias Soc. 2018, 22, 588. [Google Scholar]

- WWF. The European Alps. Available online: https://wwf.panda.org/knowledge_hub/where_we_work/alps/problems/tourism/ (accessed on 28 August 2019).

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Pierotti, M.; Amaduzzi, A. Capocchi Overtourism: A Literature Review to Assess Implications and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.S.; Li, L.-H. Understanding visitor-resident relations in overtourism: Developing resilience for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1197–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, F. Valle Soana, Guida Storica-Descrittiva Illustrata; Corsac: Cuorgnè, Italy, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Janin, B. Un dépérissement socio-économique général. Revue de Géographie Alpine 1985, 73, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazanec, J.A.; Wöber, K.; Zins, A.H. Tourism Destination Competitiveness: From Definition to Explanation? J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, P. Strategic Planning of Territorial Image and Attractability. In Advances in Modern Tourism Research: Economic Perspectives; Matias, Á., Nijkamp, P., Neto, P., Eds.; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 233–256. ISBN 978-3-7908-1718-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzini, E.; Calzati, V.; Giudici, P. Territorial brands for tourism development: A statistical analysis on the Marche region. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M. Place branding: A review of trends and conceptual models. Mark. Rev. 2005, 5, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoz, E.M.; Melewar, T.C.; Dennis, C. The Value of Region of Origin, Producer and Protected Designation of Origin Label for Visitors and Locals: The Case of Fontina Cheese in Italy. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadonna, A.; Duglio, S. A Mountain Niche Production: The Case of Bettelmatt Cheese in the Antigorio and Formazza Valleys (Piedmont–Italy). Qual. Access Success 2016, 17, 150. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Morgan, M.; Song, P. Students’ travel behaviour: A cross-cultural comparison of UK and China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Eves, A. Construction and validation of a scale to measure tourist motivation to consume local food. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1458–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peira, G.; Bollani, L.; Giachino, C.; Bonadonna, A. The Management of Unsold Food in Outdoor Market Areas: Food Operators’ Behaviour and Attitudes. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grybovych, O.; Lankford, J.; Lankford, S. Motivations of wine travelers in rural Northeast Iowa. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2013, 25, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Beltrán, J.; López-Guzmán, T.; Santa-Cruz, F.G. Gastronomy and tourism: Profile and motivation of international tourism in the city of Córdoba, Spain. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2016, 14, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rita, P.; Brochado, A.; Dimova, L. Millennials’ travel motivations and desired activities within destinations: A comparative study of the US and the UK. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2034–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachino, C.; Truant, E.; Bonadonna, A. Mountain tourism and motivation: Millennial students’ seasonal preferences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Aguilar, A.; Yagüe Guillén, M.J.; Villaseñor Roman, N. Destination brand personality: An application to Spanish tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E. Place branding as a strategic spatial planning instrument. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2015, 11, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.; Rahman, Z. Place branding research: A thematic review and future research agenda. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2016, 13, 289–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.-L.; Cheng, S.; Guo, Y.; Ma, J.; Sun, J. The impact of the cognition of landscape experience on tourist environmental conservation behaviors. J. Mt. Sci. 2015, 12, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Qiu, Z.; Nakamura, K. Tourist preferences for agricultural landscapes: A case study of terraced paddy fields in Noto Peninsula, Japan. J. Mt. Sci. 2016, 13, 1880–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, F.; Sánchez, I. The landscape as a tourist resource and its impact in mountain areas in the South of Castilla-La Mancha (Spain). Int. J. SDP 2016, 11, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, A.; Teichmann, K.; Peters, M. Do mountain tourists demand ecotourism? Examining moderating influences in an Alpine tourism context. Turizam Međunarodni Znanstveno-Stručni Časopis 2015, 63, 383–398. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, Y.-N. A study on the ecotourism cognition and its factors. Appl. Ecol. Env. Res. 2017, 15, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nössing, L.; Forti, S. Important geosites and parks in the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Dolomites. Boletín Geológico y Minero 2016, 127, 693–702. [Google Scholar]

- Baláž, B.; Štrba, L.; Lukáč, M.; Drevko, S. Geopark development in the Slovak Republic-alternative possibilities. In Proceedings of the SGEM 2014-International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConferences: Ecology and Environemntal Protection, Albena, Bulgaria, 17–26 June 2014; Volume 2, pp. 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos-Lascurain, H. Tourism, ecotourism, and protected areas: The state of nature-based tourism around the world and guidelines for its development. In Tourism, Ecotourism, and Protected Areas: The State of Nature-Based Tourism around the World and Guidelines for Its Development; International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Gland, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, J.A.; Sherman, P.B. Economics of Protected Areas. Ambio 1991, 20, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Birinci, S. An example of a protected area which has been opened to tourism: Tunca Valley Natural Park (NE Turkey). Eco. Mt. J. Prot. Mt. Areas Res. 2018, 10, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, S.K. Tourism in protected areas: The Nepalese Himalaya. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 661–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, S.K. Mountain Ecotourism and Sustainable Development. Mt. Res. Dev. 2002, 22, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, N. Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories; International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Gland, Switzerland, 2008; ISBN 978-2-8317-1086-0. [Google Scholar]

- Eagles, P.F.J.; McCool, S.F.; Haynes, C.D. Sustainable Tourisum. in Protected Areas: Guidelines for Planning and Management; Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series; IUCN—The World Conservation Union: Gland, Switzerland, 2002; ISBN 978-2-8317-0648-1. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer, R.; Fennell, D.A. Managing protected areas for sustainable tourism: Prospects for adaptive co-management. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D. The distinctive dynamics of exurban tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2005, 7, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioan, I. Protected Areas, Mountains and Tourism. Qual. Access Success 2015, 16, 300–305. [Google Scholar]

- Laurens, L.; Cousseau, B. La valorisation du tourisme dans les espaces protégés européens: Quelles orientations possibles? The enhanced value of tourism in Europe’s protected areas: Which possible directions? In Proceedings of the Annales de Géographie; JSTOR: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 240–258. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, D.B. A broad context model of destination development scenarios. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B. Organic, incremental and induced paths to sustainable mass tourism convergence. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duglio, S.; Letey, M. The role of a national park in classifying mountain tourism destinations: An exploratory study of the Italian Western Alps. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 1675–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Lucia, M.; Franch, M. The effects of local context on World Heritage Site management: The Dolomites Natural World Heritage Site, Italy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1756–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, I.; Pardo, M. Tourism versus nature conservation: Reconciliation of common interests and objectives —An analysis through Picos de Europa National Park. J. Mt. Sci. 2018, 15, 2505–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, T.; Siegrist, D. Protected Areas in the Alps: The Success Factors of Nature-Based Tourism and the Challenge for Regional Policy. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2008, 17, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzmann, E.; Job, H. Developing a typology of sustainable protected area tourism products. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1736–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinica, V. The environmental sustainability of protected area tourism: Towards a concession-related theory of regulation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, D.; Bonnelame, L.K. Nature-based tourism and nature protection: Quality standards for travelling in protected areas in the Alps. Eco. Mt. J. Prot. Mt. Areas Res. 2017, 9, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B.; Lawton, L.J. A new visitation paradigm for protected areas. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramo, R.; Rostagno, A.; Bonadonna, A. Land Consolidation Associations and the Management of Territories in Harsh Italian Environments: A Review. Resources 2018, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, G.; Cavallero, A. Rispondenza e Significato Delle Metodologie Applicate alla Realizzazione di Catasti Pastorali Sulle Alpi Occidentali; SIA Società Italiana Agronomia: Foggia, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Probo, M.; Cavallero, A.; Lonati, M. Gestione Associata delle Superfici Agro-Pastorali del Comune di Pragelato (TO); DISAFA, Università Degli Studi di Torino: Torino, Italy, 2016; ISBN 978-88-99108-07-6. [Google Scholar]

- McNicol, B.; Rettie, K. Tourism operators’ perspectives of environmental supply of guided tours in national parks. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2018, 21, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkayali, N.; Kesimoğlu, M.D. The stakeholders’ point of view about the impact of recreational and tourism activities on natural protected area: A case study from Kure Mountains National Park, Turkey. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2015, 29, 1092–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Gilli, M.; Bollani, L. Analysis and Segmentation of Visitors in a Natural Protected Area: Marketing Implications. Manag. Sustain. Tour. Resour. 2018, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, M.; Zeren, I.; Sevik, H.; Cakir, C.; Akpinar, H. A study on the determination of the natural park’s sustainable tourism potential. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swim, J.K.; Clayton, S.; Howard, G.S. Human behavioral contributions to climate change: Psychological and contextual drivers. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, A. From Sublime Landscapes to “White Gold”: How Skiing Transformed the Alps after 1930. Environ. Hist. 2014, 19, 78–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Unsustainable consumption: Basic causes and implications for policy. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonzanigo, L.; Giupponi, C.; Balbi, S. Sustainable tourism planning and climate change adaptation in the Alps: A case study of winter tourism in mountain communities in the Dolomites. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, M.; Mohamed, B.; Omar, S.I. The Influence of Perceived Environmental Impacts of Tourism on the Perceived Importance of Sustainable Tourism. e-Rev. Tour. Res. 2015, 12, 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecka, M.; Boley, B.B.; Strzelecka, C. Empowerment and resident support for tourism in rural Central and Eastern Europe (CEE): The case of Pomerania, Poland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvenegaard, G.T. Visitors’ perceived impacts of interpretation on knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions at Miquelon Lake Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groulx, M.; Lemieux, C.J.; Lewis, J.L.; Brown, S. Understanding consumer behaviour and adaptation planning responses to climate-driven environmental change in Canada’s parks and protected areas: A climate futurescapes approach. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 1016–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavaglia, V.; Diolaiuti, G.; Smiraglia, C.; Pasquale, V.; Pelfini, M. Evaluating Tourist Perception of Environmental Changes as a Contribution to Managing Natural Resources in Glacierized Areas: A Case Study of the Forni Glacier (Stelvio National Park, Italian Alps). Environ. Manag. 2012, 50, 1125–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Innes, J.L. Conservation equity for local communities in the process of tourism development in protected areas: A study of Jiuzhaigou Biosphere Reserve, China. World Dev. 2019, 124, 104637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Smith, L. Bonding and dissonance: Rethinking the Interrelations among Stakeholders in Heritage Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberghien, G. Managing the Planning and Development of Authentic Eco-Cultural Tourism in Kazakhstan. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 494–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-L.; Lin, C.; Lin, C.-W.R.; Wu, K.-J.; Sriphon, T. Ecotourism development in Thailand: Community participation leads to the value of attractions using linguistic preferences. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescimanno, A.; Ferlaino, F.; Rota, F.S. Classificazione della marginalità dei piccoli comuni del Piemonte. 2008. Available online: http://www.anci.piemonte.it/sito2016/attachments/article/222/Studio%20IRES.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2019).

- IRES, P. Piemonte Rurale 2016 Dati sul Settore Primario e Principali Tendenze Nelle Aree Rurali; IRES: Turin, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT VI Censimento Agricoltura. Available online: http://dati-censimentoagricoltura.istat.it/Index.aspx (accessed on 28 August 2019).

- Ilic, S.; LeJeune, J.; Ivey, M.L.L.; Miller, S. Delphi expert elicitation to prioritize food safety management practices in greenhouse production of tomatoes in the United States. Food Control 2017, 78, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Lin, M.; Shieh, C.-J. Performance evaluation of basic-level farmers’ associations introducing customer relationship management. Custos Agronegocio Line 2018, 14, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Tapio, P.; Rintamäki, H.; Rikkonen, P.; Ruotsalainen, J. Pump, boiler, cell or turbine? Six mixed scenarios of energy futures in farms. Futures 2017, 88, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.P.W. Role of components of destination competitiveness in the relationship between customer-based brand equity and destination loyalty. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Chi, X. Application of Delphi-AHP-DEA-FCE Model in Competitiveness Evaluation of Sports Tourism Destination. Int. J. Simulation Syst. Science Tech. 2015, 16, 20.1–20.5. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, S.; Kuo, Y.-H. Study on performance evaluation of service design in tourism industry with data envelopment analysis. Actual Probl. Econ. 2013, 2, 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Garrod, B. Applying the Delphi method in an ecotourism context: A response to Deng et al.’s Development of a point evaluation system for ecotourism destinations: A Delphi method. J. Ecotour. 2012, 11, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Cebador, M.; Rubio-Romero, J.C.; Pinto-Contreiras, J.; Gemar, G. A model to measure sustainable development in the hotel industry: A comparative study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.-H.; Hsu, Y.-S.; Wong, J.-Y.; Liu, S.-H. Sustainable international tourist hotels: The role of the executive chef. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1873–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun Wang, J.; Wang, Y.-C.; Tai, Y.-F. Systematic review of the elements and service standards of delightful service. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1310–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lateh, N.; Yaacob, S.E.; Rejab, S.N. Applying the Fuzzy Delphi Method (FDM) to Analyze the Expert Consensus Values for Instrument of Shariah-Compliant Gold Investment. Soc. Sci. Hum. 2017, 25, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, B. Predicting the Future: Have you considered using the Delphi Methodology? J. Ext. 1997, 35, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ulschak, F.L. Human Resource Development: The Theory and Practice of Need Assessment; Reston Pub. Co.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1983; ISBN 978-0-8359-2996-7. [Google Scholar]

- Đogić, I.; Cerjak, M. Local stakeholders perception on development possibilities of Croatian islands—Example of the island of Cres. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2015, 16, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguí-Mas, E.; Marí-Vidal, S.; del Mar Marín-Sánchez, M. Business Failure Prediction in Agricultural Cooperatives through Non Financial Variables. An Approach through the Delphi Method. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), Valencia, Spain, 13–14 May 2014; IBIMA: Valencia, Spain, 2014; pp. 1418–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Bender, M.; Selin, S. Development of a point evaluation system for ecotourism destinations: A Delphi method. J. Ecotour. 2011, 10, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, Q.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Y. The application of Delphi method in improving the score table for the hygienic quantifying and classification of hotels. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2009, 43, 287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wu, N.; Xu, R.; Li, L.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, X. Empirical analysis of pig welfare levels and their impact on pig breeding efficiency—Based on 773 pig farmers’ survey data. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0190108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ng, E.; Huang, S.-C.; Fang, W.-T. A Self-Evaluation System of Quality Planning for Tourist Attractions in Taiwan: An Integrated AHP-Delphi Approach from Career Professionals. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-B.; Kim, K.-H.; Choo, H. The Development of Quality Standards for Rural Farm Accommodations: A Case Study in South Korea. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 673–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, L.; Ye, Y.; Zhao, X.; Guo, X.; Xie, W. Evaluation on Influence of Land Consolidation Project on Cultivated Land Quality Based on Agricultural Land Classification Correction Method. Available online: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/tcsae/tcsae/2016/00000032/00000017/art00027# (accessed on 22 July 2019).

- Jiang, M.; Yu, M.; Li, H. Construction and application of evaluation index system of agricultural scientific and technological progress under the background of modern agriculture—An empirical research based on statistical data of Ningbo City. In Proceedings of the 2014 21th Annual International Conference on Management Science Engineering, Helsinki, Finland, 17–19 August 2014; pp. 1698–1706. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.; Chen, W.; Li, M.; Bai, Y.; Pan, Y. GIS-based study of the spatial distribution suitability of livestock and poultry farming: The case of Putian, Fujian, China. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2014, 108, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.J.; Shi, L. Evaluation index system of sustainable livelihoods ecotourism strategy: A case study of wangjiazhai community in baiyangdian wetland nature reserve, Hebei. Shengtai Xuebao Acta Ecol. Sin. 2014, 34, 2388–2400. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Zhao, G.; Wang, J.; Cheng, J.; Meng, Y.; Dong, C.; Lei, T. Restoration and Reutilization Evaluation of Coastal Saline-Alkaline Degraded Lands in Yellow River Delta. Available online: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/tcsae/tcsae/2009/00000025/00000011/art00057 (accessed on 22 July 2019).

- Kaufmann, P.R. Scenario making and analysis in spatial planning: Scenarios of spatial development for Dalmatia until 2031. Ann. Anali za Istrske Mediter. Stud. Ser. Hist. Sociol. 2017, 27, 581–598. [Google Scholar]

- Rikkonen, P.; Tapio, P. Future prospects of alternative agro-based bioenergy use in Finland—Constructing scenarios with quantitative and qualitative Delphi data. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2009, 76, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sabek, L.M.; McCabe, B.Y. Framework for Managing Integration Challenges of Last Planner System in IMPs. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugé, J.; Mukherjee, N. The nominal group technique in ecology & conservation: Application and challenges. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Crovato, S.; Pinto, A.; Arcangeli, G.; Mascarello, G.; Ravarotto, L. Risky behaviours from the production to the consumption of bivalve molluscs: Involving stakeholders in the prioritization process based on consensus methods. Food Control 2017, 78, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeta, J.; Barrutia, J.; Lertxundi, A. Hybrid Delphi: A methodology to facilitate contribution from experts in professional contexts. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2011, 78, 1629–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabbe, M.J.C. Sustainable Tourism and Management for Coral Reefs: Preserving Diversity and Plurality in a Time of Climate Change. JSSM 2010, 03, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harvey, N.; Holmes, C.A. Nominal group technique: An effective method for obtaining group consensus. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2012, 18, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, H.A.; Rapport, F.L.; Wright, S.; Doel, M.A. Obtaining Consensus from Mixed Groups: An Adapted Nominal Group Technique. J. Adv. Med. Med. Res. 2013, 1, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, J.; Castiglioni, A.; Stanford Massie, F.; Russell, S.W.; Shaneyfelt, T.; Willett, L.L.; Estrada, C.A.; Kraemer, R.R.; Morris, J.L.; Rodriguez, M. Evaluation of an Advanced Physical Diagnosis Course Using Consumer Preferences Methods: The Nominal Group Technique. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 347, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankin, N.M.; McGregor, D.; Butow, P.N.; White, K.; Phillips, J.L.; Young, J.M.; Pearson, S.A.; York, S.; Shaw, T. Adapting the nominal group technique for priority setting of evidence-practice gaps in implementation science. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, D.M. Facilitating public participation in tourism planning on American Indian reservations: A case study involving the Nominal Group Technique. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formica, S.; Kothari, T.H. Strategic destination planning: Analyzing the future of tourism. J. Travel Res. 2008, 46, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfeld, Y.; Jonas, A. Evaluating the socio-cultural carrying capacity of rural tourism communities: A ‘value stretch’approach. Tijdschrift Voor Economische Sociale Geografie 2006, 97, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, P.-J.; Lin, S.-Y. Research Note: Resort Hotel Location. Tour. Econ. 2011, 17, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, H.M.; Needham, R.D. Moving best practice forward: Delphi characteristics, advantages, potential problems, and solutions. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konu, H. Developing nature-based tourism products with customers by utilising the Delphi method. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 14, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, M.; Ziglio, E. Gazing into the Oracle: The Delphi Method and Its Application to Social Policy and Public Health; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 1996; ISBN 978-1-85302-104-6. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchio, R.; Annunziata, A. Consumers’ attitudes towards sustainable food: A cluster analysis of Italian university students. New Medit 2013, 12, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Clonan, A.; Holdsworth, M.; Swift, J.; Wilson, P. Awareness and Attitudes of Consumers to Sustainable Food. In Ethical Features: Bioscience and Food Horizons; Millar, K., Hobson West, P., Nerlich, B., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publisher: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M. Methodology for close up studies—Struggling with closeness and closure. High. Edu. 2003, 46, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.A.; Shaffir, W. Standards for Field Research in Management Accounting. J. Manag. Account. Res. 1998, 10, 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R.; McDonald, C.D.; Riden, C.M.; Uysal, M. Community attachment, regional identity and resident attitudes toward tourism. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Travel and Tourism Research Association Conference; Travel and Tourism Research Association: Wheat Ridge, CO, USA, 1995; pp. 424–428. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold, S.; Dolnicar, S. How Airbnb Creates Value. In Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Networks; Dolnicar, S., Ed.; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-911396-51-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gios, G.; Goio, I.; Notaro, S.; Raffaelli, R. The value of natural resources for tourism: A case study of the Italian Alps. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2006, 8, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuščer, K. Determining factors of mountain destination innovativeness. J. Vacat. Mark. 2013, 19, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Shi, H.; Yang, D.; Ren, X.; Cai, Y. Analysis of core stakeholder behaviour in the tourism community using economic game theory. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 1169–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duglio, S.; Beltramo, R. Environmental management and sustainable labels in the ski industry: A critical review. Sustainability 2016, 8, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presenza, A.; Del Chiappa, G.; Sheehan, L. Residents’ engagement and local tourism governance in maturing beach destinations. Evidence from an Italian case study. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).