Abstract

The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between teachers’ organizational commitment, job satisfaction and whistleblowing behaviors and to evaluate their contribution to sustainability in education. The study consisted of a total of 4108 teachers who worked at primary and secondary schools during the 2018–2019 academic year in the Çankaya district of the Ankara province. The sample comprised of 601 teachers who were selected through a simple random sampling method. The organizational Commitment Scale (OCS), the Job Satisfaction Scale (JSS) and the Whistleblowing Scale were used as the data collection tools in the study. For the analysis of the data, SPSS 18.0 and LISREL 8.80 statistical package programs were used. Descriptive statistics on variables were performed on SPSS program and the testing of the model in which the effects of job satisfaction on whistleblowing and organizational commitment on job satisfaction were studied was carried out using path analysis technic in LISREL 8.80 program. According to the results of the study, there was a moderate level of positive and significant relationship between organizational commitment and job satisfaction. There was also a moderate level of positive and significant relationship between organizational commitment and whistleblowing behaviour. A low level of negative significant relationship was found between job satisfaction and whistleblowing. As the teachers’ organizational commitment increased, their job satisfaction and whistleblowing behaviours also increased. However, as their job satisfaction levels increased, their whistleblowing behaviours decreased. In this regard, it can be concluded that sustainability in educational institutions can be ensured by increasing the level of organizational commitment.

1. Introduction

Organizations are social structures that gather in order to achieve certain goals. Organizations should take care of their internal environment as much as their external environment in order to reach their goals to adapt to the conditions changing and improving day by day, to be able to compete and to increase their performance and activities. Organization employees are one of the most important factors that affect the internal environment of an organization. In this respect, employees’ positive organizational behaviours would contribute to the organization’s achievement of goals and success. One of the positive organizational behaviours is organizational commitment. It can be stated that the existence of employees who adopt their organization’s goals and aims as their own is a condition which promotes the organizational survival. Among the goals of an organization are to enable the employees’ job satisfaction and to assure their organizational adoption. By these means organizations can have highly adopted employees. Research in this area proves that the importance of organizational commitment for organizations gradually increases [1].

It is clear that organizational commitment has an impact on many organizational behaviours and it is also affected by other organizational behaviours. It is also seen that the concepts of job satisfaction and whistleblowing have recently entered the field of interest among organizations and researchers. In particular, whistleblowing takes place among the new topics which the discipline of organizational behaviour is interested in. In this study, the relationship between organizational commitment, job satisfaction and the whistleblowing behaviours of teachers as employees of educational organization was analysed in terms of the sustainability of organizational commitment.

2. Conceptual Framework

In this part of the study, the concepts of organizational commitment, job satisfaction and whistleblowing were evaluated.

2.1. Organizational Commitment

Recently, the concept of “organizational commitment” has become one of the most interesting and emphasized topics.

Some of the most commonly used concepts among these are Protestant business ethics based on the Christian faith, suggested by Mirels and Garrett [2], Greenhaus and Simon’s [3] description of prioritizing the career (the importance of a job or a career in a person’s life), description of binding strictly to one’s job by Lodahl and Kejner [4], Dubin’s [5] approach of seeing one’s business as the center of life (the place where the individual prefers to perform his/her business) and the description of organizational commitment suggested by Mowday, Steers and Porter [6] in 1974.

According to the significant descriptions in the literature, organizational commitment can be defined in the following ways:

Porter et al. [7]: “Having positive attitudes supported by feelings of hard work and making these attitudes permanent on behalf of the organization being included”. Porter et al. also described organizational commitment in another way: “the voluntary high effort of the employee, the strong desire s/he has to stay in the organization and her/his adoption of the basic rules and values of the organization.”

Morrow [8]: “A multidimensional perception that is seen as the employee’s desire to stay in the organization and to strive for it and to internalize the goals and values of the organization.”

Salancik [9]: “Having an affection towards what is done and the desire to continue doing it even the reward is unclear.”

Wiener’e [10]: “The total of normative pressures internalized in order to act to meet organizational goals and interests.”

Sheldon [11]: “Attitudes and tendencies of a person which connect him to the organization or which tailors his/her identity to the organization.”

In the current age of achieving success and profit, job satisfaction and the sustainability of these concepts are some of the most important goals of organizations. In order to accomplish their goals, organizations and researchers are striving to understand the cognitive and sensual concepts about organizations and put these findings into practice. One of the most vital concepts about organizations is organizational commitment.

Organizational commitment is defined as the employee’s loyalty to the organization s/he is included in. It is related with some concepts such as performance, productivity, personal turnover and satisfaction [12].

Porter et al. [7] have stated that “organizational commitment is the relative strength of an individual’s identity in a particular organization”. According to Meyer and Allen [13], “individuals who have strong emotional commitment stay in the organization because they want, others need to have stronger normative commitment because they have strong commitment since they need it”. Emotional commitment is the psychological bonding towards organization. Organization means “a positive feeling towards organization which is reflected in the desire of seeing the organization reach its goals and feeling proud of being a part of that organization” [14]. Continued commitment is a situation related with disengagement from the organization. It means “the awareness of the individual towards the cost of leaving the organization” [15].

An employee who has continued commitment finds it difficult to leave his/her organization because of the fear of “opportunity costs” which has few or no alternatives when leaving the organization. Individuals who have high levels of such kind of commitment stay members of the organization because they need it. The perceived engagement of normative commitment has impacts on the individual’s continual involvement in the organization [15]. In other words, it can be stated that emotional commitment occurs when one wants to stay as an employee while continued commitment is when the employee needs to stay within the organization. Normative commitment occurs when the employee feels the need to stay in the organization [15,16].

Studies on commitment have suggested evidence on the negative relationship between performance and organizational results, such as citizenship behaviour and continued commitment, while emotional commitment and normative commitment have positive relationship [17]. The study also proves that employees with a higher level of emotional commitment show higher levels of continuity and normative commitment to their jobs and careers [18].

2.2. Job Satisfaction

One of the most important aspects of organizational sustainability is to include the employee in the organization. The adoption of organizational aims and goals by the employees carries the organization a step further. At this point, job satisfaction of the employees is a critical aspect.

Upon studying the literature, it is not possible to talk about a common attitude about the description of job satisfaction. There are various definitions of job satisfaction.

- Hackman and Oldman [19] defined job satisfaction as feeling glad about the job done.

- Job satisfaction is one of the most important factors for the productivity and activity of business organizations. The rationale behind job satisfaction is the happiness of a satisfied employee; a happy employee is a successful employee [20].

- Job satisfaction is the financial gain and happiness in which the employee produces an output together with his colleagues with whom s/he likes working [21].

- Job satisfaction is a condition related with the level of meeting the expectations of attitudes towards various aspects of work and the outputs gained [22].

- Job satisfaction is the feeling of contentment as a result of positive attitudes towards factors such as business and social environment, wages, working conditions, opportunities of improvement [23].

- Job satisfaction is the total satisfaction of a job with all its aspects [24].

- The fact that job satisfaction is related to conditions such as commitment to the job and organization, alienation to the job, performance, being punctual and leaving work on time, highlights the importance of this concept for organizations [25].

With the neoclassical management approach, the idea of satisfying the employees has gained importance.

The individual is seen as the most important resource in management understanding. The organizations which improve the levels of satisfaction of their employees are able to create a sustainable environment while increasing their productivity [26].

Internal dynamics have a greater effect on the success of organizations, in the conjuncture where competition is at a high level. One of the most prominent factors among internal dynamics is job satisfaction. Being the most important factor of production, satisfaction of the individual creates a positive impact on organizational performance and provides a basis for a successful structure. Moreover, organizational activities like harmony between colleagues, a fair payment system, opportunities for promotion and employee-centered management structure increase the satisfaction levels of employees. The increase in satisfaction positively affect the organizational development, function, success and stability [27].

There are some points on which organizations should pay greater attention to while creating job satisfaction. These points are job enrichment, job rotation, uncovering the talent of staff, increasing emotional support, improving performance characteristics, involving more employees in the solution of problems, increasing commitment to organizational goals and increasing motivational elements [28].

There is a difference between the satisfaction felt by accomplishing a job and the satisfaction felt during the work. Satisfaction, according to when it is felt, can be classified as internal and external satisfaction. Satisfaction felt by external rewards on accomplishing a job is called “external satisfaction”, while satisfaction felt internally during the job is called “internal satisfaction” [29]. The employee starts working considering that their needs will be met and he agrees to achieve the goals of the organization. Dissatisfaction occurs when the employee starts thinking that there is no balance between his efforts and fulfillment of his expectations. The organizations which can exist with their employees can face difficulties in surviving due to the absenteeism and abandonment of work on low job satisfaction. The most important mission of managers is to ensure job satisfaction of the employees along with production. The employee compares his/her expectations from work and the output s/he obtains. S/he also compares his/her own labour and the things s/he gets with other employees whom s/he considers as his/her own equivalent. As a result of this comparison, s/he feels satisfied if s/he has the same level or more acquisition. The equivalent status as a result of this comparison is the basic essential emotion required for job satisfaction [30]. Internal or external sources and self-made obstacles which prevent the individual from obtaining his goals can sometimes lead to complex feelings and thoughts in the employee. Such conditions can also affect job satisfaction and organizational commitment as well. The psychological and physical well-being of employees should not be ignored in order to enable a healthy growth, development and achievement of an organization [31] (p. 41).

2.3. Whistleblowing

Whistleblowing is a process by which third parties are informed about damaging actions. There are various definitions of whistleblowing [32,33,34,35,36]. Near and Miceli [34] have a commonly held definition about whistleblowing. Before setting the definition, the concept was discussed socially, morally and legally; then, it was defined as the disclosure of immoral, illicit and unlawful actions of the employees under the control of the employers by other organization members. This definition of whistleblowing is accepted by the empirical researchers [36,37,38,39]. According to this commonly accepted definition, whistleblowing (a) shows that there are wrongdoings in an organization, (b) provides motivation with the desire to prevent other organization members from getting harmed, (c) expresses worries about misconduct in the organization or in an independent structure connected to that organization, (d) mostly informs the authorities about malpractice, and (e) transmits information about malpractice to the press [40].

While defining whistleblowing, some of the factors that lead to this action should be emphasized. First, the whistleblower witnesses or is exposed to immoral actions or procedures in the organization. Thus, s/he is in a struggle for the welfare of the organization and the employees, which sets whistleblowing apart from any espionage behaviour [36]. Another factor is that whistleblowing has a moral and ethical basis. It is a critical action in order to stop an unfavourable action [40]. Whistleblowing behaviour is thought to have a connection with personal morality and virtue. People who show this behaviour are featured to react to unethical illegitimate actions anywhere and anytime, to reject wrongdoings because they are conscientiously disturbed by malpractices in the organization and fall into disagreement with their managers or colleagues. The ethical and moral side of whistleblowing is emphasized and organizational development is supported by this behaviour while preventing unethical, unlawful actions in an organization [38]. As a result, whistleblowing is taking action, depending on individual ethical principles and moral development, considering the organizational benefits rather than individual interests.

Whistleblowers are the people who reveal malpractices or unethical actions in an organization. A whistleblower may be a current or a former employee of an organization. Whistleblowers believe that the organization is aware that it gives harm to third parties or it engages in activities that violate human rights [41]. Therefore, the whistleblower should decide whether the acts s/he observes are a mistake. Robinson and Bennett [42] have put forth a typology of perverted workplace behaviour. The focus of whistleblowers is negative or wrong behaviours, decisions or instructions even to the organization or the members of the organization. The wrongdoings mentioned here are stated to change within the scope of two dimensions and to have four types. The first dimension of wrongdoings is the Minor and Severe dimension. This dimension expresses the severity of perverted behaviours. The second dimension is the interpersonal and organizational dimension. This dimension represents the target of perverted behaviours. It is seen that misconfiguration in the organization has an influence on the intention of whistleblowing.

According to Miceli and Near [43], employees are the most influential elements that can diminish malpractices in an organization; the response they show about malpractices is denouncement. However, the witness of malpractice may not prefer whistleblowing due to fear of retaliation. Greene and Latting [44] and Zhang et al. [45] expressed that 90% of whistleblowers do this by hiding their identities. Moreover, denunciation is accepted as a taboo in most countries. For instance, it is perceived as a negative action in Türkiye [46]. Verschoor’s [47] research revealed that 44% of the witnesses of a crime do not report their observations to anybody.

Dozier and Miceli [48] stated that the decision of whistleblowing is influenced by the person’s characteristic features and his/her environment. Miceli et al. [49] expressed the possible connection between employees’ emotions and whistleblowing intentions.

A person can whistleblow without giving any names. Park et al. [50] have introduced a whistleblowing type based on three dimensions. Each dimension is reported to represent the individual’s whistleblowing choice, either officially or informally, internally or externally, declared or anonymously. Whistleblowing refers to the act of informing people about insecurity while denunciation means false accusation of people via official organizational communication channels [50]. Denunciation is misinforming an institutional inspector internally, whereas whistleblowing is reporting misinformation to the outsiders, who are believed to have the power, in order to fix something.

Observers tend to whistleblow more when they believe that there are effective internal denunciation/complaint channels in the organization. On the other hand, when society or the employees are harmed, the malpractice is denounced externally [50]. When the observer gives his/her true identity or any information about him/herself, s/he has started to whistleblow. Nevertheless, the observer may anonymously whistleblow using a code name or without giving any information [50]. Among the factors that affect whistleblowing are the organization’s legal regulations to encourage whistleblowing and the employees’ having no retaliation concerns. The encouraging attitudes of the management or the employees may decrease the risk of retaliation. The power range and the cultural background in a community and dominant bureaucratic culture are believed to block whistleblowing. On the other hand, since cultures with collectivist values hold organizational interests above personal interests, they encourage whistleblowing [45]. In addition to organizational culture, cultural values of the employees are also influential on whistleblowing behaviour. In this respect, having an encouraging organizational culture and policy is essential for denouncing unethical and unlawful actions, which encourages employees toward whistleblowing and contributes to organizational improvement.

Disclosure of the practices which prevent organizations to reach their goals by sharing this with management, other organizations and colleagues in the organization, is individually, organizationally and socially essential.

Whistleblowing is considered as an important tool for increasing the effectiveness and sustainability of organizations. Therefore, ways to increase effectiveness of organizations by whistleblowing have been searched for since 1990s. Some of these investigations are mentioned above. However, whistleblowing is not known enough by either managers nor employees in Türkiye. With this study, managers of business and public institutions in Türkiye are expected to gain awareness on whistleblowing. When the managers fully understand how internal whistleblowing contributes to organizational climate and productivity, they will use it for organizational sustainability. Managers of organizations will tend to support internal whistleblowing, which will make employees see themselves as important elements in the organization and contributing to the organizational productivity by internally whistleblowing. Thus, the correction of mistakes in the organization will be possible without harming anybody, and the employees will adopt the organization.

2.4. The Correlation between Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction and Whistleblowing

The models explaining whistleblowing emphasize commitment as a personal trait which influence job satisfaction, commitment and the power of decision-making [35]. Therefore, organizational commitment and job satisfaction are the two most important points to improve organizational behaviours.

Organizational commitment refers to the devotion of an employee to his/her institution while job satisfaction expresses the positive emotions of an employee towards his/her business role [51]. Job satisfaction creates positive emotions for a certain job, whereas organizational commitment shows the level of devotion to an organization [52]. While some researchers suggest a connection between job satisfaction and organizational commitment [52], Currivan [51] found no significant correlation between these two concepts.

According to Near and Miceli [34], whistleblowers consider themselves as very loyal employees and try to whistleblow internally. If they are punished for this, they use external whistleblowing. Whistleblowers believe that they act loyally and help managers by attracting their attention to the malpractices in the organization. According to Micelli et al. [35], whistleblowers are seen as employees who have a high level of organizational loyalty.

The aim of this study was to detect the correlation between teachers’ organizational commitment, job satisfaction and whistleblowing behaviours. In order to reach this aim, answers to the questions below were sought:

- According to teachers’ perception, what is the realization level of organizational commitment, job satisfaction and whistleblowing behaviours?

- According to teachers’ perception, what is the level of correlation between organizational commitment, job satisfaction and whistle blowing?

- According to teachers’ perception, do the behaviours of organizational commitment, job satisfaction and whistleblowing behaviours have a significant difference according to

- 3.1.

- Gender,

- 3.2.

- Age,

- 3.3.

- Seniority,

- 3.4.

- Marital Status,

- 3.5.

- Educational Status,

- 3.6.

- Training Level,

- 3.7.

- Branch?

3. Method

In this part of the study, information on research model, universe and sample, data collection tools, data collection and data analysis took place.

3.1. Research Model

The study was designed using a relational scanning model. A relational scanning model is a research model which aims to define the presence and/or degree of a large number of variables between two or more variables [53].

The event, subject or object of the research was defined in that present condition and was not changed, by any means [53] (p.33).

There are three variables in the research model, two of which are dependent/internal (job satisfaction and whistleblowing) and one of which is independent/external (teachers’ organizational commitment levels). The job satisfaction variable can also be expressed as a mediator in the structural model. One of the most important advantages of path analysis is being able to define a mediator variable between the predictive variable and the predicted variable [54] (p.340).

3.2. Universe and Sample

The study consisted of a total of 4108 teachers who worked at primary and secondary schools in the Çankaya district of the Ankara province during the academic year 2018–2019.

A simple random sampling method was used to detect the sample. In this method, all the units in the universe have an equal and independent chance to be selected for the sample. Random sampling is the best and the most valid way to select a representative sample [55], (p.84). A total of 601 teachers could be reached after determining which schools would be included in the sample.

Gender, age, seniority, marital status, educational status, training level and branch variables of the teachers are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Gender, age, seniority, marital status, educational status, training level and branch variables of the teachers in the study.

Upon examination of Table 1, it is seen that of the teachers who participated in the study, approximately one out of five were male,, nearly half were between 41 and 50 years of age, nearly half had a teaching experience of 21–30 years, four-fifths were married and at graduate level, two-thirds taught at secondary school and one third taught social sciences.

3.3. Data Collection Tools

As data collection tools, the Organizational Commitment Scale (OCS), the Job Satisfaction Scale (JSS) and the Whistleblowing Scale were used in this study.The necessary consent for using the determined measuring tools was obtained. The item numbers in these scales were determined as 18, 5 and 16, respectively, and the scale form for the participants was prepared. In addition to these scales, the research form had a section containing gender, age, seniority, marital status, educational background, level of education and personal information of the participants. Detailed information on measurement tools is also included below. Before starting the path analysis, measurement tools that were planned to be included in the model were tested one by one by a confirmatory factor analysis in order to provide a significant assumption of the relational scanning model. This process contributes to the validity and reliability of a path model [54] (p.339).

3.4. Collection and Analysis of Data

Legal permissions to apply the scales for collecting data were obtained from the General Directorate of Innovation and Technologies of the Ministry of National Education in Ankara. The scales were applied on a voluntary basis. The data were collected between December 2018 and March 2019. The scale forms were taken to and then collected from the sampling schools by the researcher himself in order to contribute effectively to the purpose of the research.

Validity and reliability studies were performed for the OCS, JSS and Whistleblowing Scale.

For the analysis of the data, SPSS 18.0 and LISREL 8.80 statistics package programs were used. Descriptive statistics for the variables were obtained using SPSS and the model on which the effect of job satisfaction on whistleblowing and organizational commitment on job satisfaction was studied was tested in LISREL 8.80 by using a path analysis technique.

3.5. Results

According to the perceptions of the teachers, organizational commitment, job satisfaction and whistleblowing behaviours and path analysis findings related to these levels and the differences between variables according to gender, age, seniority, marital status, educational status, training level and branches are included.

Findings Related to the First Sub-Problem

According to the perceptions of the teachers, the results of the organizational commitment levels are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Commitment levels of the teachers.

When Table 2 is examined, it is seen that the teachers’ commitment to continuity (= 3.31) was higher than their emotional (= 3.14) and normative commitment (= 2.79). In addition, it can be said that the emotional commitment (S = 0.55) has a more homogeneous distribution than continuity (S = 0.67) and normative commitment (S = 0.90). In other words, the teachers’ commitment to attendance is higher than the emotional and normative commitment. It can also be said that the teachers’ organizational commitment is at a moderate level.

According to the perceptions of the teachers, the findings related to the job satisfaction levels are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Job satisfaction levels of the teachers.

When Table 3 is examined, it is seen that the teachers’ high score was given to “I enjoy my job a lot” (= 4.01) and the lowest score was given to “My job is like a hobby to me.” (= 3.27)

It is seen that the most homogenous distribution took place in “I enjoy my job a lot.” (S = 1.03) and the most heterogeneous distribution took place in “My job is like a hobby to me.” (S = 1.43) when the standard deviation values were examined. In other words, the job satisfaction of the teachers was at the mostly level.

According to the teachers’ perceptions, findings related to whistleblowing levels are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Whistleblowing levels of the teachers.

When Table 4 is examined, it is seen that the supportive whistleblowing behaviours of the teachers (x = 3.33) are higher than internal (X = 2.50), secret (X = 2.62) and external (X = 2.50) whistleblowing behaviours. In addition, it can be said that the most homogenous distribution occurs for whistleblowing (S = 0.94) and the most heterogenous distribution occurs for secret whistleblowing behavior (S = 1.07). In other words, teachers react to the most supportive and least external whistleblowing behaviour. Additionally, the whistleblowing behaviours of the teachers actualize at a “moderate” level.

Findings Related to Second Sub-Problem

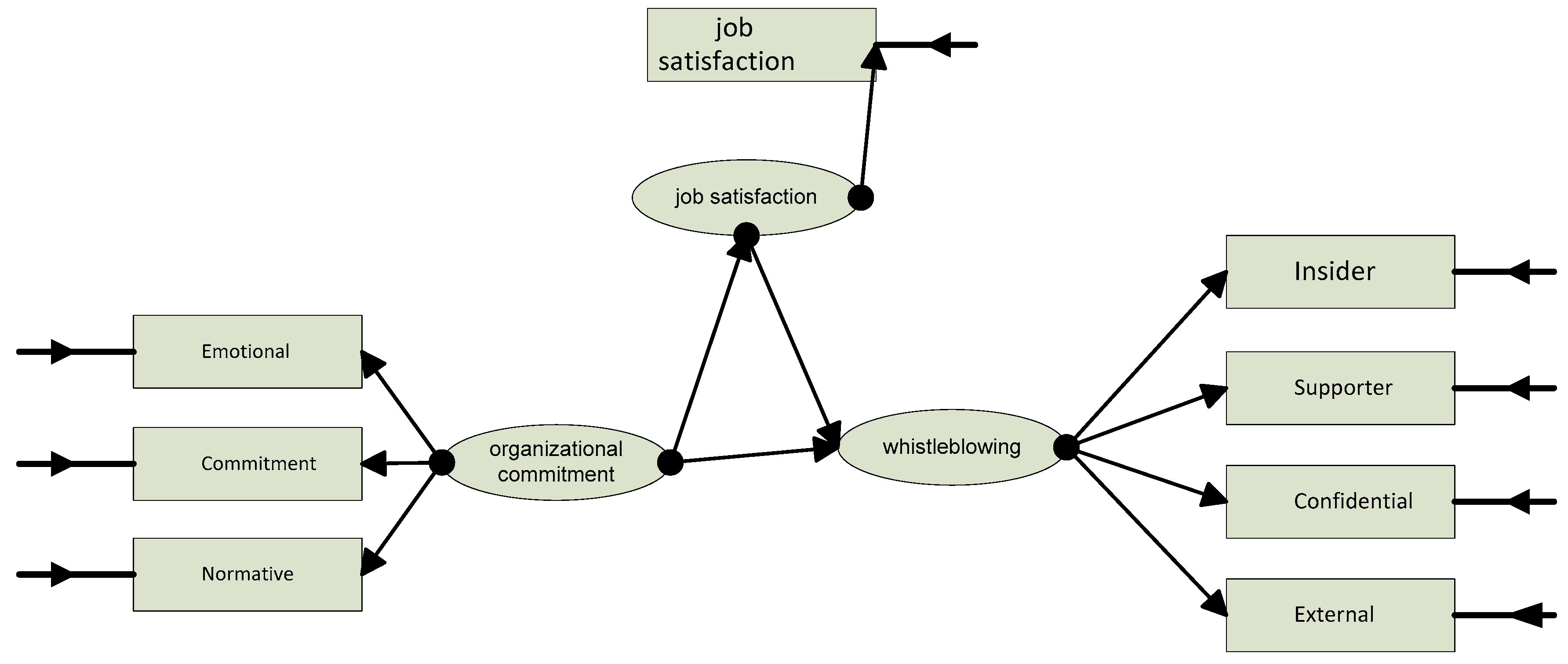

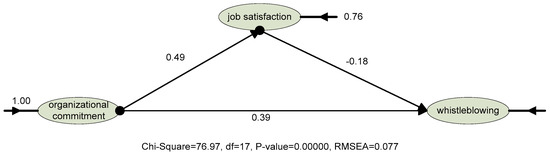

In order to determine the level and direction in which teachers’ organizational commitment levels affect job satisfaction and whistleblowing behaviours, a path analysis was carried out. The path analysis reveals the direct and indirect effects of the predictor variables on the predicted variables. The conceptual model is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

In the conceptual model in Figure 1, it is assumed that the teachers’ perceptions of organizational commitment affect job satisfaction and whistleblowing levels and that job satisfaction predicts the whistleblowing levels. In addition, it is predicted that the organizational commitment of the teachers has indirect effects on whistleblowing behaviours. In the model, one latent variable is defined as external (organizational commitment) and two latent variables are defined as internal (job satisfaction and whistleblowing).

In this study, organizational commitment was determined by an independent latent variable; emotional, continuity and normative commitment indicators. It is assumed that the job satisfaction dependent latent variable will be explained by the indicators that are obtained with IDDO and constitute the job satisfaction score. It is accepted that the whistleblowing dependent latent variable is explained by internal, supportive, confidential and external whistleblowing indicators.

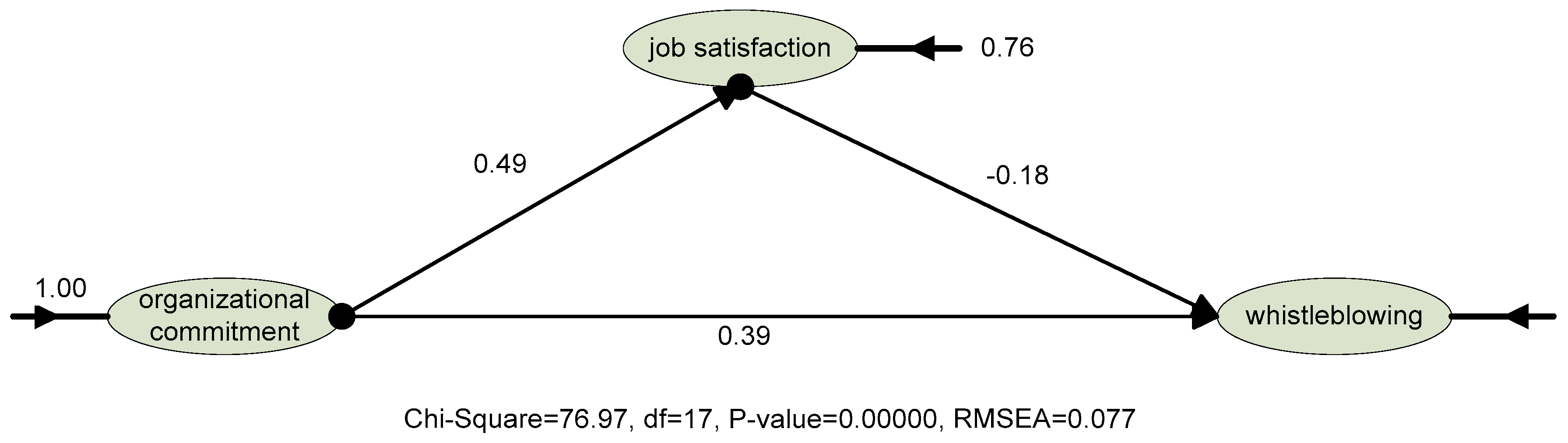

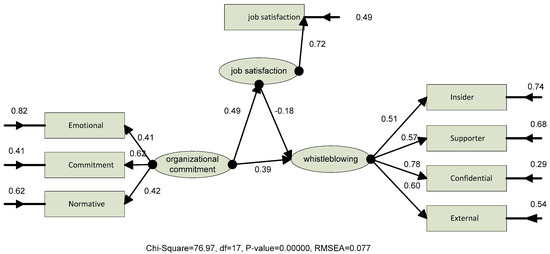

Then, it was found that the data set does not provide the assumption of multivariate normality (p ≤ 0.05). Therefore, it was decided to use the Robust Unweighted Least Squares estimation method, which is recommended to be used in cases where the data is not normally distributed [56]. The structural model obtained as a result of the analysis is given in Figure 2 and the representation of SEM is given in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structural model of research.

First, the findings of the statistical convenience of YEM were examined. Kline [56] (p. 204) recommended a x2/sd ratio, where the x2 value is examined with sd, to be used as a criterion for adequacy when evaluating the convenience of the model. In this study, the x2/sd value was obtained as 4.53. In other words, the data set is in accordance with the model [57].

Later, alternative accordance indices related to the model were examined.

When Table 5 is examined, it is seen that the model generally shows good compliance values; these values are acceptable and it is confirmed as a model.

Table 5.

Compliance values of the model to path analysis.

The critical N-CN value, where the adequacy of the research sample was evaluated, was calculated as 261.44. This value shows that the 601 unit samples used in the research are sufficient.

The results corelated with the YEM results are given in Table 6.

Table 6.

The YEM results related with the research.

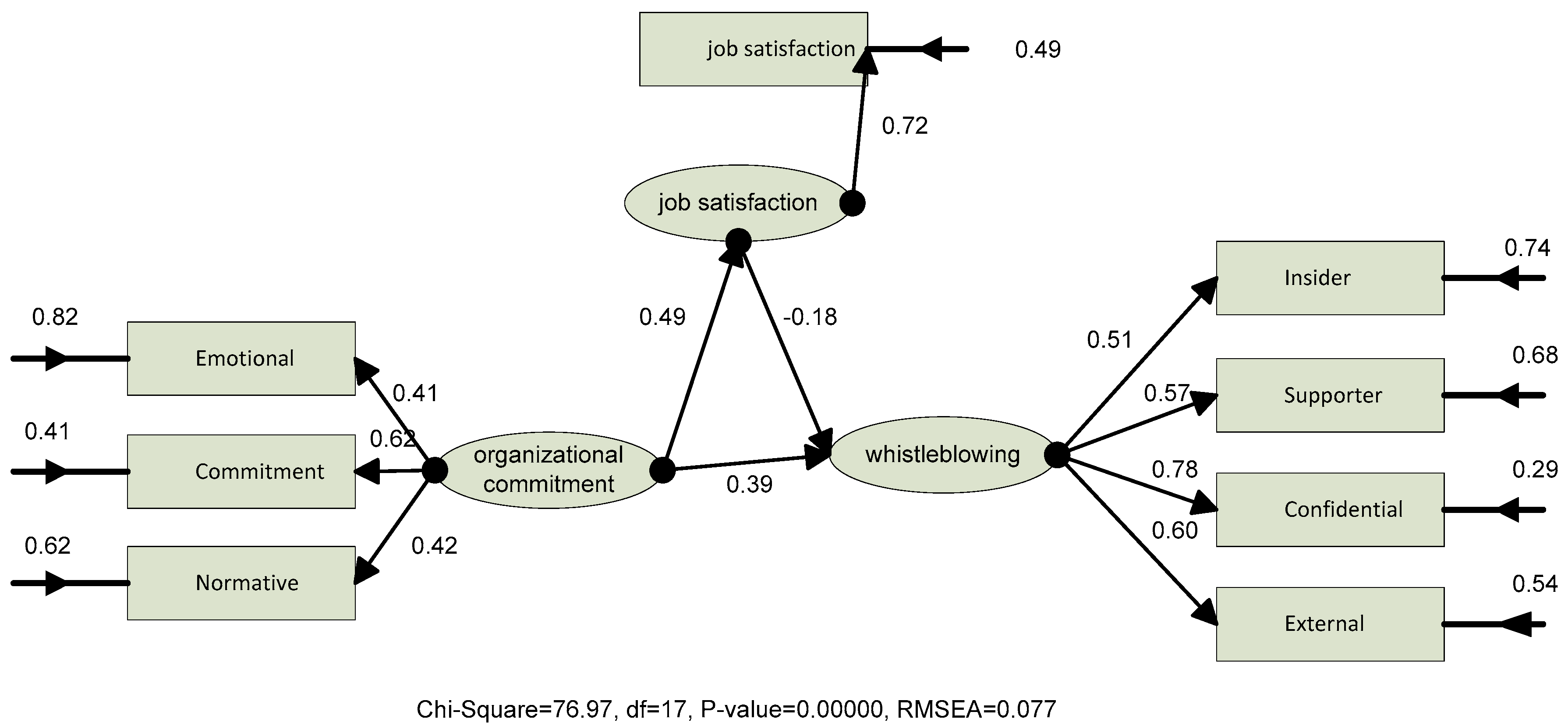

Related to LISREL, beta (β) is the regression of a dependent (internal) latent variable over another dependent latent variable; gamma (γ) is the correlation coefficient of a regression of an independent latent variable on a dependent latent variable. Furthermore, the coefficient of determination which is defined as the variance described (R2), indicates how much the variables involved in structural equation explain the observed changes. The factor loads between the latent variable and the observed variable are indicated by lambda (λ) (Çelik and Yılmaz, 2013, s.17). When the findings of the model are examined, continuity commitment (λ = 0.62; t = 3.27) is the best indicator of whistleblowing (λ = 0.78; t = 8.05) seems to indicate secret whistleblowing (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Structural equation model established for research.

There is a positive and significant relationship between organizational commitment and job satisfaction at a moderate level (γ = 0.49; t =3.14). This value indicated that a 1point increase in organizational commitment leads to a 0.49-point increase in job satisfaction and vice versa, a 1-point decrease in organizational commitment leads to a 0.49-point decrease in job satisfaction. In other words, job satisfaction level increased as long as the organizational commitment of the teachers increased.

There was a positive and significant relation between organizational commitment and whistleblowing. This value indicates that a 1 point increase in organizational commitment leads to a 0.39 point increase in whistleblowing, and vice versa, a 1 point decrease in organizational commitment leads to a 0.39 point decrease in whistleblowing.

A negative and significant relationship between job satisfaction and whistleblowing at a low level was found (γ = 0.39; t = 3.08). This value indicates that a 1-point increase in job satisfaction will result in a 0.18% point decrease in whistleblowing, and vice versa, a 1 = point decrease in job satisfaction will result in a 0.18% point increase in whisleblowing. In other words, as the teachers’ job satisfaction increased, whistleblowing decreased.

Organizational commitment explains 24% of job satisfaction. In other words, 24% of the total change in teachers’ job satisfaction is explained by the level of organizational commitment.

It is seen that organizational commitment and job satisfaction together explain 12% of whistleblowing. This finding can be interpreted as 12% of the total change in whistleblowing variable bring explained by the direct effect of organizational commitment and the job satisfaction variable. In addition, organizational commitment has a stronger predictive effect on whistleblowing than job satisfaction. As the organizational commitment of the teachers increased, job satisfaction and whistleblowing behaviours increased.

However, as job satisfaction levels increased, whistleblowing decreased.

Findings Related to Third Sub-Problem

According to teachers’ perceptions, organizational commitment levels, gender, age, seniority, marital status and branch variables were examined.

According to Table 7, the levels of organizational commitment of teachers, gender (t (599) = 1.60; p > 0.05] and the training level [t (599) = 0.16; p > 0.05]. In other words, teachers’ organizational commitment did not differ according to gender and training level.

Table 7.

t-test results of organizational commitment scale according to gender and education level.

According to Table 8, the organizational commitment of the teachers [F (3597) = 1.14; p > 0.05] do not show significant difference related to age, marital status [F (2,598) = 0.14; p > 0.05], education level [F (3597) = 0.89; p > 0.05] and area [F (3597) = 1.25; p > 0.05]. However, there was a difference related to seniority [F (3597) = 4.01; p < 0.05].

Table 8.

ANOVA results of organizational commitment scale scores by age, seniority, marital status, training level and area.

In other words, the organizational commitment levels of teachers vary according to their seniority According to the results of the Scheffe test, the organizational commitment levels of teachers with 31 years or more (= 3.19) were found to be more positive than teachers with 11–20 years (= 2.99).

According to Table 9, teachers’ job satisfaction levels do not show a significant difference related to seniority [t (599) = 0.06; p > 0.05]. The job satisfaction of teachers working in primary schools is more positive than teachers working in secondary schools. In other words, the job satisfaction of the teachers varies according to the education level [t (599) = 2.31; p < 0.05].

Table 9.

T-Test results of job satisfaction scale scores according to gender and education level.

According to Table 10, teachers’ job satisfaction levels did not show a significant difference according to age [F (3597) = 2.57; p > 0.05, marital status [F (2598) = 0.08; p > 0.05] and area [F (3597) = 2.19; p > 0.05. However, there was a significant difference according to seniority [F (3597) = 6.96; p <0.05]. According to the results of the Scheffe test, the job satisfaction level of the teachers with 31 years of seniority was found to be more positive than teachers with less seniority. In other words, the job satisfaction levels of the teachers varried depending on their seniority. In addition, the job satisfaction levels of the teachers showed a significant difference according to their education level.

Table 10.

ANOVA results of job satisfaction scale scores by age, seniority, marital status, training level and branch.

According to the results of the Scheffe test, it was determined that the job satisfaction levels of teachers with associate degree were more positive than teachers with undergraduate graduation. In other words, teachers’ job satisfaction levels vary depending on their education.

According to Table 11, the levels of whistleblowing of teachers did not differ significantly according to gender [t (599) = 0.79; p > 0.05] and education level. In other words, teachers’ whistleblowing did not differ according to gender and educational level (t (599) = 1.39; p > 0.05].

Table 11.

Whistleblowing scale according to gender and educational level by t-test.

According to Table 12, the level of whistleblowing of teachers does not show a significant difference according to age [F (3597) = 2.65; p > 0.05], seniority [F (3597) = 0.97; p > 0.05], marital status [F (2598) = 1.06; p > 0.05] and area [F (3597) = 1.06; p > 0,05]. However, a significant difference in educational status [F (3597) = 3.54; p < 0.05] is seen. According to the results of the Scheffe’s test, it is determined that the whistleblowing levels of the teachers with bachelors’ degree (= 2.97) were higher than teachers with associate degree (= 2.61). In other words, teachers’ whistleblowing behaviours varies depending on their educational background.

Table 12.

ANOVA results according to age, seniority, marital status, education level and area.

4. Discussion

According to the results of Gökçe’s study [58] “Whistleblowing in Schools: The Correlation between Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment”, most common actions witnessed by teachers were evaluated. Whistleblowing was found out to have a significant positive correlation with the teachers’ seniority. This result does not support the study. Among the results of the study is the fact that teachers still prefer whistleblowing informally. The fact that there is no significant difference on account of job satisfaction does not support the results. Near and Michelin [59] argued that there is a correlation between job satisfaction and whistleblowing although they cannot suggest the effect of job satisfaction on whistleblowing clearly. The results of this study support their argument because according to the results, there is a low level of negative significant correlation between job satisfaction and whistleblowing. The results show that teachers show a supportive whistleblowing attitude the most and an external whistleblowing attitude the least; studies in the literature support these results [46,58,59]. The conclusion that seniority has no correlation with whistleblowing does not support the literature [44,46,48,58,59].

There was a moderate level of positive significant correlation between organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Previous studies support this research [60,61,62,63,64].

A moderate level of positive significant correlation between organizational commitment and whistleblowing was also found. However, upon reviewing the literature, it was found that studies investigating these two concepts are limited [58]. The fact that there is a limited number of studies on the relationship between positive organizational behaviours and whistleblowing emphasizes the importance of this research.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to detect the relationship between teachers’ organizational commitment, job satisfaction and whistleblowing behaviours and to evaluate their contribution to sustainability in education. The concepts of organizational commitment, job satisfaction and whistleblowing, whose importance in organizational discipline is undeniable, were attempted to be explained after reviewing the literature. It was found that there is a limited number of studies in the literature which use these three concepts together and therefore, this subject is thought to enrich the literature. Its contribution to later studies is also considered important. The results found in the light of the findings of this study are given in this section.

Regarding the perception of teachers, when the findings on the level of organizational commitment were studied, it was seen that teachers’ commitment to continuity is at a higher level than their emotional and normative commitment. In addition, emotional commitment has a more homogenous distribution compared to continuity and normative commitment. Moreover, teachers’ organizational commitment was found to be at a ‘moderate’ level.

Regarding the perception of teachers, when the findings on job satisfaction levels were examined, it was seen that the highest score was given to the items ‘I enjoy my job a lot’ and the lowest score to ‘My job is like a hobby to me’. When the standard deviation values were examined, the most homogenous distribution was seen to be on the item ‘I enjoy my job a lot’, and the most heterogeneous distribution was found on the item ‘my job is like a hobby for me’. In other words, teachers’ job satisfaction was on a ‘generally’ level.

Regarding the perception of teachers, when the findings on whistleblowing behaviours were examined, it was seen that teachers’ supportive whistleblowing behaviours were at a higher level than internal, secret and external whistleblowing behaviours. In addition, the most homogenous distribution occurred in internal whistleblowing and the most heterogenous distribution occurred in secret whistleblowing behaviour. In other words, teachers perform supportive whistleblowing behaviour the most and external whistleblowing the least. Moreover, they have a ‘moderate’ level of whistleblowing.

A positive significant correlation at a moderate level was found between organizational commitment and job satisfaction, which means that as teachers’ organizational commitment increased, their job satisfaction levels rose.

A moderate level of positive significant correlation was found between organizational commitment and whistleblowing behaviour. That is to say, as the level of organizational commitment rose, the teachers’ whistleblowing degrees increased.

It was found that there was a low level of negative significant correlation between job satisfaction and whistleblowing. In other words, as level of job satisfaction rose, whistleblowing behaviours tended to cease.

Organizational commitment accounted for 24% of job satisfaction. That is to say that 24% of the total variance in teachers’ job satisfaction can be explained with organizational commitment levels. In addition, organizational commitment accounted for 9% of whistleblowing, which means that 9% of the total variance in whistleblowing can be explained with organizational commitment.

Organizational commitment and job satisfaction are seen to account for 12% of whistleblowing. This finding can be interpreted as 12% of the total change in whistleblowing variable and can be explained by the direct effect of organizational commitment and job satisfaction latent variables and the indirect effect of the job satisfaction variable. Furthermore, organizational commitment had a stronger precursor effect on whistleblowing compared to job satisfaction. In other words, the higher organizational commitment the teachers have, the more job satisfaction and whistleblowing behaviours they perform. However, as the job satisfaction levels increased, the whistleblowing behaviours decreased.

There was no significant difference between the teachers’ organizational commitment levels and gender and training levels, which means that teachers’ organizational commitment did not change according to their gender the level at which they teach. The level of organizational commitment did not show a significant difference according to age, marital status, educational status and branch. However, there was a significant difference according to seniority. According to the results of the Scheffe test, which was carried out in order to find out which groups had unit-based differences, teachers who had more than 31 and more years of seniority had a more positive organizational commitment compared those who had a seniority of 11–20 years. In other words, teachers’ organizational commitment levels differed according to their seniority in their jobs.

The job satisfaction levels of teachers had no significant difference according to gender. However, it differed significantly according to the level at which the teacher worked. Teachers who worked at primary school had a more positive job satisfaction compared to those who worked at a secondary school. That is to say, the job satisfaction levels of teachers change according to the level of school they work in. The level of job satisfaction had no significant difference according to age, marital status and branch of the teacher. However, there was a significant difference according to seniority. The Scheffe test results show that teachers who had more than 31 years of seniority had a more positive job satisfaction level compared to the teachers who were less experienced. In other words, job satisfaction levels differ according to seniority. In addition to this, job satisfaction levels have a significant difference according to educational status. The Scheffe test results showed a more positive job satisfaction level for associate degree graduate teachers compared to undergraduate teachers. That is to say, the job satisfaction levels of teachers differed according to educational status.

The whistleblowing levels of teachers did not show a significant difference according to gender and the level of schools at which they worked. In other words, teachers’ whistleblowing behaviours did not differ depending on gender and the training levels. Whistleblowing behaviours did not indicate any significant difference according to age, seniority, marital status and branch. However, there was a significant difference depending on the educational status. Depending on the results of the Scheffe test, undergraduate teachers had a higher level of whistleblowing behaviour compared to associate degree teachers. This means that teachers’ whistleblowing behaviours differ depending on their educational status.

As organizational commitment increased, job satisfaction and whistleblowing behaviours also increased. Within this scope, it can be concluded that sustainability in educational institutions can be obtained by increasing the organizational commitment levels.

6. Recommendations

In order to ensure sustainability in educational institutions, to support life-long learning, to pave the way for leadership, entrepreneurship and creativity, the recommendations below should be implemented:

- Present managers should be able to analyze the expectations of employees very well and make an effort to help them feel emotional organizational commitment rather than normative and continuity commitment.

- Managers should develop some practices that would increase emotional commitment.

- Managers should give the employees autonomy and responsibility in their jobs.

- Managers should increase job satisfaction and organizational commitment using some incentive rewards such as salaries, bonuses and premiums.

- Managers should give feedback and performance assessments regularly, on time and impartially.

- Managers should perform some motivating activities.

- The effect of psychological and structural factors should be evaluated in whistleblowing.

- Managers should always keep communication channels open with their stakeholders.

- In order to gain awareness about ethical values in the organization, all the employees should be provided with an effective training.

- Taking whistleblowing rate in our country into account, this behaviour should be encouraged in organizations by making it perceived as a positive behaviour and making it work in the organizations.

- Whistleblowing behaviour should be transformed into an internal auditing mechanism; misbehaviours could be settled before making it known externally.

- The relationship between organizational commitment, job satisfaction and whistleblowing should light the way for sustainability and the relationship between education and management.

- The relationship between organizational commitment, job satisfaction and whistleblowing should ensure organizational aims are reached and resources effectively used and play an effective role in carrying out the economical process of life-long learning in the institution and in detecting and solving the problems in the institution for the sustainability of the organization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.Ö.; methodology, M.E.Ö.; software, M.E.Ö.; validation, M.E.Ö., U.A. and N.C.; formal analysis, M.E.Ö.; investigation, U.A.; resources, N.C.; data curation, M.E.Ö.; writing—original draft preparation, U.A.; writing—review and editing, N.C.; visualization, U.A.; supervision, U.A.; project administration, N.C.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Erdoğan, D. Resmi İlköğretim Okullarındaki Sınıf Öğretmenlerinin Örgütsel Bağlılık Düzeylerinin İncelenmesine Yönelik Bir Araştırma. Master’s Thesis, Beykent Üniversitesi, İstanbul, Turkey, 2009. in press (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Mirels, J.E.; Garrett, D.M. A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates and consequences of organizational commitment. Physcological Bull. 1976, 108, 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, M.W.; Simon, P.E. Principals and job satisfaction. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 1977, 12, 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Lodahl, R.; Kejner, E.R. Age, education, job tenure, salary, job characteristics, and job satisfaction: A multivariate analysis. Hum. Relat. 1965, 38, 781–791. [Google Scholar]

- Dubin, A. Antecedents of organizational commitment across occupational groups: A Meta-Analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 1956, 13, 539–554. [Google Scholar]

- Mowday, R.; Steers, R.; Porter, L. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 12, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.; Steers, R.; Mowday, R.; Boulian, P. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 13, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, D.J. Occupational commitment, education, and experience as a predictor of ıntent to leave the nursing profession. Nurs. Econ. 2006, 24, 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Salancik, G.R. Commitment and The Control of Organization Behaviorand Belief, New Directions in Organization Behavior; İllionis St. Clair Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1977; pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener, Y. Commitment in organizations: A normative view. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, C.R. Information, cognitive biases and commitment to a course of action. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 300–310. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, J.E.; ve Hamel, D. A Cause Model of the Antecedents of Organizational Commitment among Professionals and Non-Professionals. J. Vocat. Behav. 1989, 34, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A. Multiple Commitments in the Workplace; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.; Smith, C. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 8, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suma, S.; Lesha, J. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment: The case of shkodra municipality. Eur. Sci. J. 2013, 9, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, R.D.; Bycio, P.; Hausadorf, P. Further assessment of Meyer and Allen’s 1991 three components model of organizational commitment. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 17, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. On the discriminant validity of the Meyer and Allen measure of organizational commitment: How does ıt fit with the work commitment construct. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1996, 56, 494–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.; Oldham, G. Development of the job diagnostic survey. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziri, B. Job satisfaction: A litarature review. Manag. Res. Pract. 2011, 3, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Şimşek, M.Ş.; Akgemci, T.; Çelik, A. Davranış Bilimlerine Giriş ve Örgütlerde Davranış; Adım Matbaacılık: Konya, Turkey, 2003; pp. 18–22. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Eren, E. Örgütsel Davranış ve Yönetim Psikolojisi; Beta Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 2014; pp. 18–22. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Çetin, F.; Basım, N. Psikolojik dayanıklılığın iş tatmini ve örgütsel bağlılık tutumlarındaki rolü. İş Güç Endüstri İlişkileri Ve İnsan Kaynakları Derg. 2011, 13, 79–94. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, Y.K. Eğitim Yönetimi: Kuram Ve Türkiye’deki Uygulama; Bilim Yayınları: Ankara, Turkey, 2011; pp. 33–38. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Eryılmaz, C. Bir iş doyumu ölçümü olarak iş betimlemesi ölçeği geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. Türk Psikol. Derg. 2017, 12, 25–55. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Telman, N.; Ünsal, P. Çalışan Memnuniyeti; Epsilon Yayıncılık: İstanbul, Turkey, 2004; p. 55. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Güven, S.; Bakan, D.; Yeşil, H. İlköğretim okulu öğretmenlerinin iş tatmini ile örgütsel bağlılığı arasındaki ilişki. Uşak Üniversitesi Sos. Bilimler Derg. 2005, 3, 74–89. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Çetin, B. İlköğretim Okulu Öğretmenlerinin Performansları Ve İş Doyum Düzeyleri. Master’s Thesis, Yeditepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, İstanbul, Turkey, 1999. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Şimşek, M.; Çelik, A.; Akgemci, T. Davranış Bilimlerine Giriş ve Örgütlerde Davranış; Eğitim: Konya, Turkey, 2016; pp. 22–26. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Başaran, İ. Örgütsel Davranış İnsansın Üretim Gücü; Siyasal Basın: Ankara, Turkey, 2008; pp. 56–57. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Samadov, S. İş Doyumu Ve Örgütsel Bağlılık: Özel Sektörde Bir Uygulama. Master’s Thesis, Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, İzmir, Turkey, 2006. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, T. A Preliminary investigation of the relationship between organizational characteristics and external whistle-blowing by employees. J. Bus. Ethics 1992, 11, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, E.S.; Collins, J.W. Employee attitudes toward whistleblowing: Management and public policy implications. J. Bus. Ethics 1992, 11, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Near, J.; Miceli, M. Organization dissidance the case of whistle blowing. J. Bus. Ethics 1985, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, M.P.; Near, J.P.; Schwenk, C.R. Who blows the whistle and Why? Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 1991, 45, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, M.P.; Near, J.P. Relationships among Value Congruence, Perceived Victimization, and Retaliation against Whistleblowers: The Case of Internal Auditors’. J. Manag. 1994, 20, 773–794. [Google Scholar]

- Miceli, M.P.; Rehg, M.; Near, J.P.; Ryan, K.C. Can laws protect whistle-blowers? Results of a naturally occurring field experiment. Work Occup. 1999, 26, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, J. Comparing Indian and American managers on whistleblowing. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2002, 14, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Near, J.P.; Rehg, M.T.; Scotter, J.R.V.; Miceli, M.P. Does type of wrongdoing affect the whistleblowing process? Bus. Ethics Q. 2004, 14, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneweg, S. Three Whistleblower Protection Models: A Comparative Analysis of Whistleblower Legislation in Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom; Public Service Commision of Canada: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2001; pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vinten, G. Whistleblowing in the Health-Related Professions. Indian J. Med. Ethics 1996, 4, 108–111. Available online: http://www.issuesinmedicalethics.org (accessed on 1 January 2011).

- Robinson, S.; Bennett, R. A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 555–572. [Google Scholar]

- Miceli, M.P.; Near, J.P. Standing up or standing by: What predicts blowing the whistle on organizational wrongdoing? Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 24, 95–136. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, A.D.; Latting, J.K. Whistleblowing as form of advocacy: Guidelines for the practitioner and organization. Soc. Work. 2004, 49, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Chiu, R.; Wei, L. Decision-making process of internal whistleblowing behavior in China: Empirical evidence and implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayir, D.; Herzig, H. Value orientations as determinants of preference for external and anonymous whistleblowing. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschoor, C. Is this the age of whistleblowers? Strateg. Financ. 2005, 86, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier, J.B.; Miceli, M.P. Potential predictors of whistle-blowing: A prosocial behavior perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, M.P.; Scotter, J.R.V.; Near, J.P.; Rehg, M.T. Individual Differences and Whistle-blowing. 2001. Available online: https://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/apbpp.2001.6133834 (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- Park, H.; Blenkinsopp, J.; Oktem, M.K.; Omurgonulsen, U. Cultural orientation and attitudes toward different forms of whistleblowing: A comparison of South Korea, Turkey, and the U.K. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currivan, D. The causal order f job satisfaction and organizational commıtment in models of employee turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1999, 9, 495–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C.; Wallace, J.; Price, J. Employee commitment resolving some issues. Work Occup. 1992, 19, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasar, N. Bilimsel Araştırma Yöntemi; Nobel Yayınevi: Ankara, Turkey, 2014; pp. 32–36. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Çokluk, Ö.; Şekercioğlu, G.; Büyüköztürk, Ş. Sosyal Bilimler İçin Çok Değişkenli İstatistik, SPSS ve LISREL Uygulamaları; Pegem: Ankara, Turkey, 2012; pp. 15–16. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Büyüköztürk, Ş.; Çakmak, E.K.; Akgün, Ö.E.; Karadeniz, Ş.; Demirel, F. Bilimsel Araştırma Yöntemleri; Pegem: Ankara, Turkey, 2011; p. 25. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 38–42. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Sümer, Ü. İşgörenlerin örgütsel bağlılıklarının meyer ve allen tipolojisiyle analizi: Kamu ve özel sektörde karşılaştırmalı bir araştırma. Anadolu Üniversitesi Sos. Bilimler Derg. 2007, 7, 224–247. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Gökçe, A. Okullarda bilgi uçurma: Iş doyumu ve örgütsel bağlılık ilişkisi. Dicle Üniversitesi Ziya Gökalp Eğitim Fakültesi Derg. 2014, 22, 261–282. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Near, J.P.; Miceli, M.P. Effective Whistle-blowing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 679–708. [Google Scholar]

- Celep, C. Eğitimde Örgütsel Adanma ve Öğretmenler; Anı Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2000; p. 15. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Erdaş, Y. Denizli İl Merkezinde Çalışan İlköğretim Öğretmenlerinin Örgütsel Bağlılık Düzeyleri. Master’s Thesis, Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Denizli, Turkey, 2009. in press (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Poyraz, K.; Kama, B. Algılanan iş güvencesinin, iş tatmini, örgütsel bağlılık ve işten ayrılma niyeti üzerindeki etkilerinin incelenmesi. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi İktisadi Ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Derg. 2008, 13, 143–164. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, J.P.; Bajpai, N. Organizational commitment and ıts ımpact on job satisfaction of employees: A comperative study in public and private sector in India. Int. Bull. Bus. Adm. 2010, 9, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmudoğlu, A. Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı Merkez Örgütünde İş Doyumu ve Örgütsel Bağlılık. Ph.D. Thesis, Abant İzzet Baysal Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Bolu, Turkey, 2007. in press (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).