Designing Powerful Learning Environments in Education for Sustainable Development: A Conceptual Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

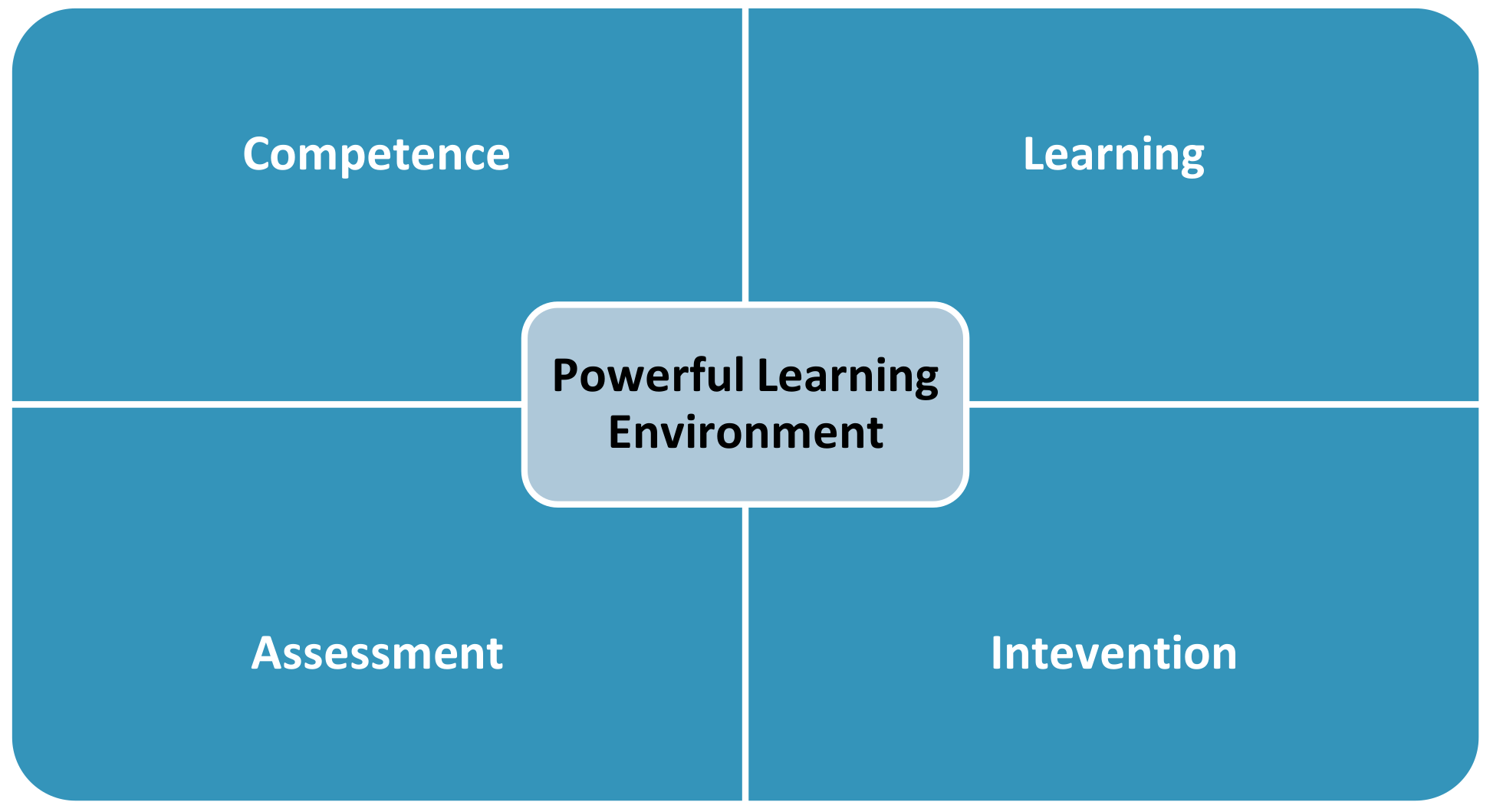

2. Powerful Learning Environments

2.1. Competence

2.2. Learning

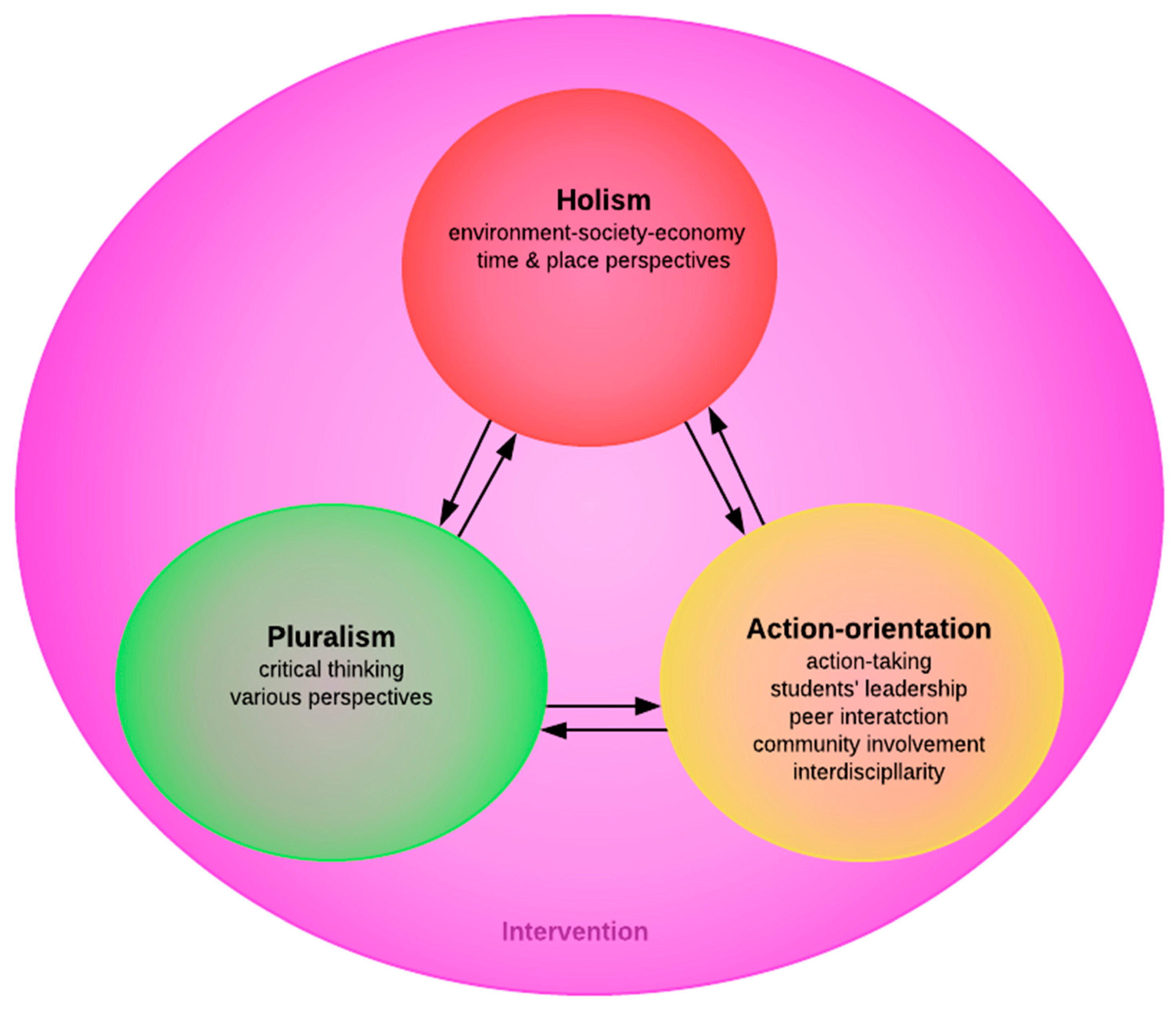

2.3. Intervention

2.3.1. Holistic Approaches to SD in ESD

2.3.2. Pluralistic Approaches in ESD

2.4. Assessment

3. Purpose and Aim of the Study

- What are the components of an action–oriented framework in Education for Sustainable Development according to the literature?

- What are the components of an integrated framework in Education for Sustainable Development developing a powerful learning environment according to the literature?

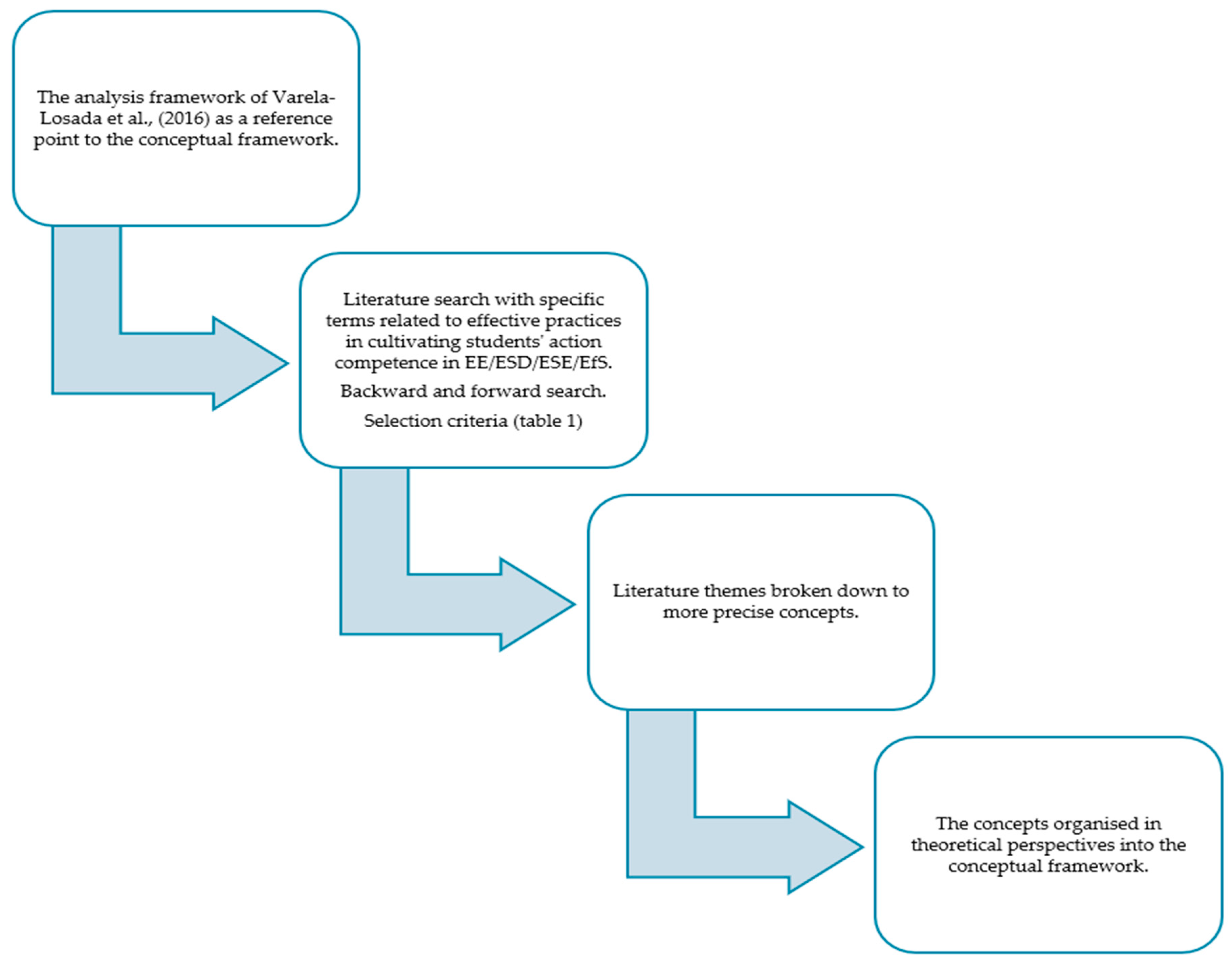

4. Methodology

5. Results

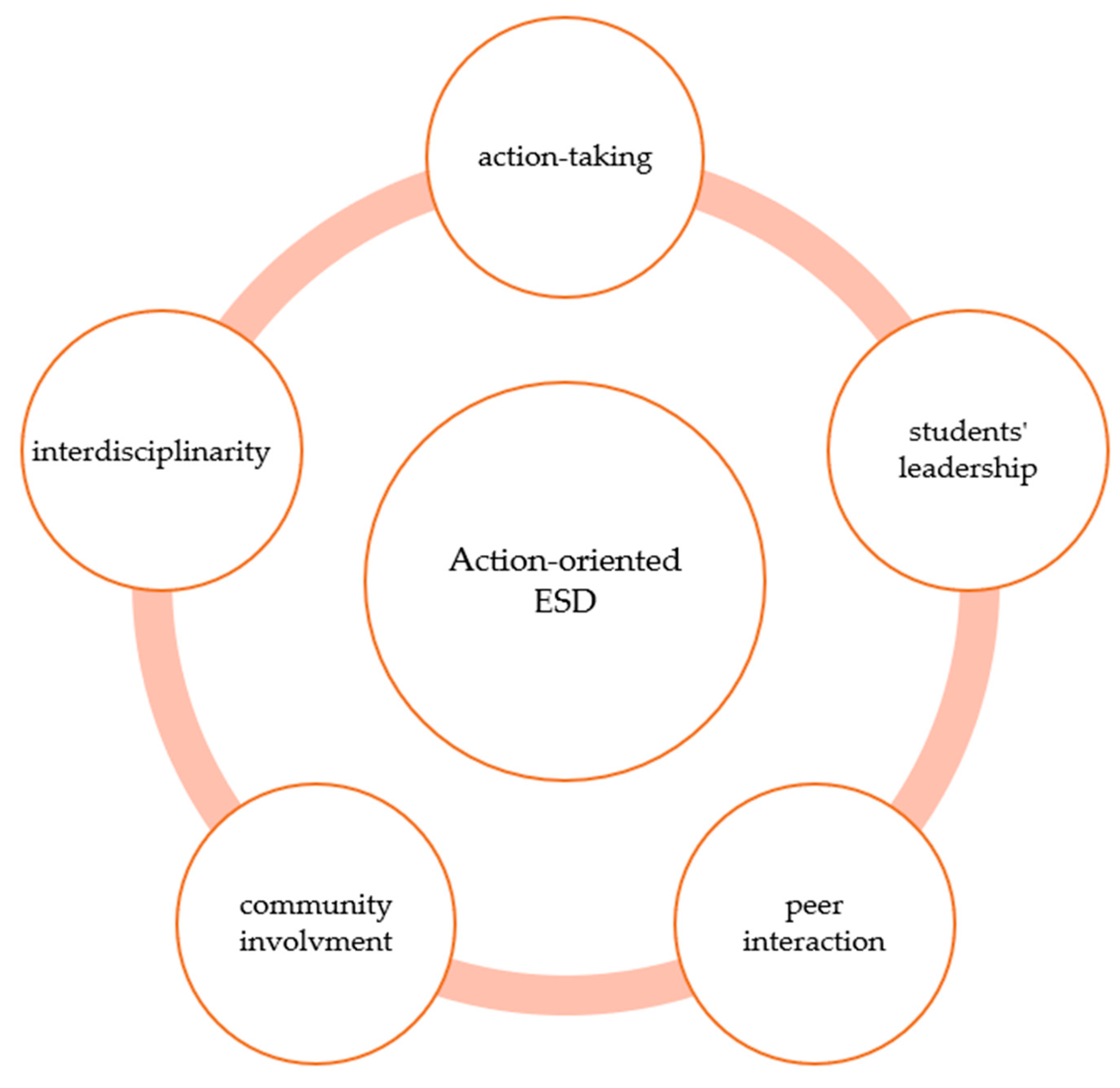

5.1. Action-Oriented ESD Framework

5.1.1. Action-Taking

Impact of Action

Context of Action

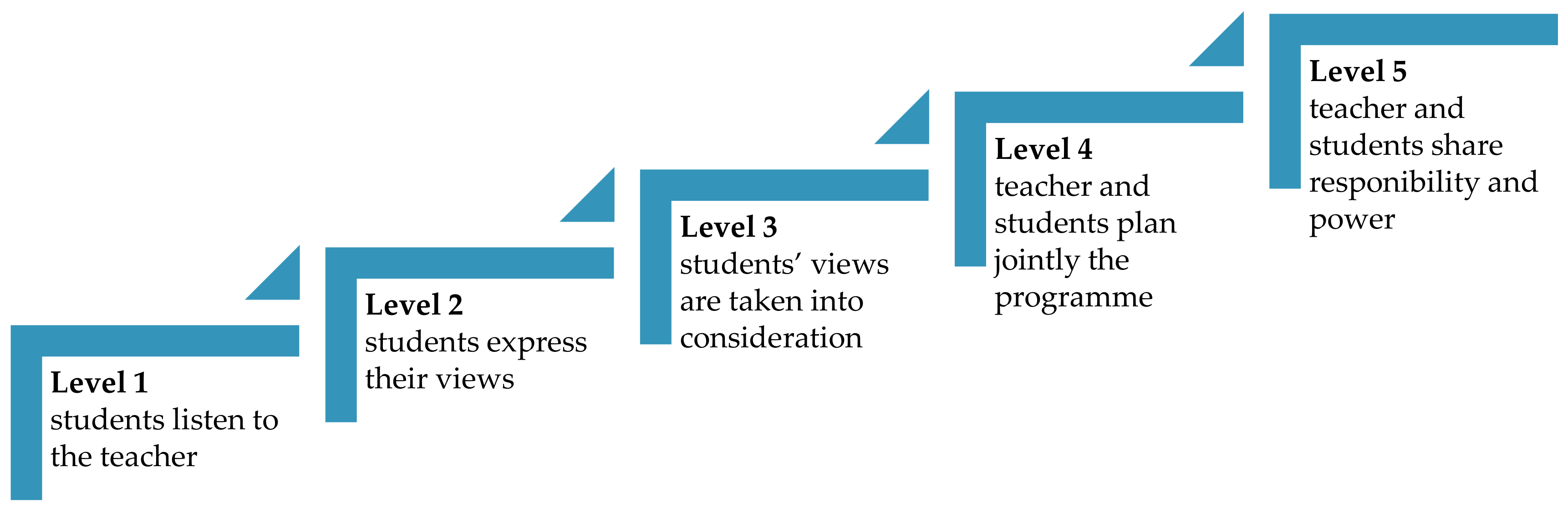

5.1.2. Students’ Leadership in Learning and Teaching

5.1.3. Peer Interaction

5.1.4. Community Involvement

5.1.5. Interdisciplinarity

5.2. The Need for the Development of the Action-Oriented Framework

6. Discussion

6.1. Implications for ESD Teaching Practice

6.2. Implications in ESD Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wals, A.E. Learning Our Way to Sustainability. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 5, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, M.; De Baz, T.; Alshawa, H. Assessing the Infusion of Sustainability Principles into University Curricula. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2016, 18, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carban, E.; Fisher, D. Sustainability reporting at schools: Challenges and benefits. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2017, 19, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, B.; Hopwood, B.; O’Brien, G. Environment, economy and society: Fitting them together into sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2002, 10, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED. Our Common Future: A Report from the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development; WCED: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Corney, G.; Reid, A. Student teachers’ learning about subject matter and pedagogy in education for sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinakou, E.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Van Petegem, P. Exploring the concept of sustainable development within education for sustainable development: Implications for ESD research and practice. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubrich, H. Geography Education for Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the Symposium: Geographical Views on Education for Sustainable Development, Lucerne, Switzerland, 29–31 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Makrakis, V. ICT-enabled reorienting teacher education to address sustainable development: A case study. In Proceedings of the 7th Pan-Hellenic Conference with International Participation: ICT in Education, Korinthos, Greece, 23–26 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wuelser, G.; Pohl, C.; Hirsch Hadorn, G. Structuring complexity for tailoring research contribution to sustainable development: A framework. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, L. Change, Uncertainty, and Futures of Sustainable Development. Futures 2006, 38, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, T.; Gericke, N.; Rundgren, S.-N.C. The implementation of education for sustainable development in Sweden: Investigating the sustainability consciousness among upper secondary students. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2014, 32, 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, H.R. Environmental Education (EE) for 21st century: Where have we been? Where are we now? Where are we headed? J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 41, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N.; Chang Rundgren, S.N. The effect of implementation of education for sustainable development in Swedish compulsory schools—Assessing pupils’ sustainability consciousness. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 176–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Corte, E.; Verschaffel, L.; Masui, C.; Corte, E. The CLIA-model: A framework for designing powerful learning environments for thinking and problem solving. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2004, 19, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Corte, E. Instructional Psychology: Overview. In International Encyclopedia of Developmental and Instructional Psychology; De Corte, E., Weinert, F.E., Eds.; Wheatons: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen, F.; Schnack, K. The action competence approach and the ‘new’ discourses of education for sustainable development, competence and quality criteria. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.B. Knowledge, Action and Proenvironmental Behaviour. Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littledyke, M. Science education for environmental awareness: Approaches to integrating cognitive and affective domains. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandell, K.; Öhman, J.; Östman, L.; Billingham, R.; Lindman, M. Education for Sustainable Development: Nature, School and Democracy; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, S. Increasing the Value of the Environment: A ’real options’ metaphor for learning. Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauw, J.B.-D.; Gericke, N.; Olsson, D.; Berglund, T. The Effectiveness of Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15693–15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, M.; Childs, A. Student science teachers’ conceptions of sustainable development: An empirical study of three postgraduate training cohorts. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2007, 25, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohman, J. Values and Democracy in Education for Sustainable Development; Contributions from Swedish Research; Liber: Malmo, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Walshe, N. Exploring and developing student understandings of sustainable development. Curric. J. 2013, 24, 224–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshe, N. An interdisciplinary approach to environmental and sustainability education: Developing geography students’ understandings of sustainable development using poetry. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 23, 1130–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, T.; Gericke, N. Separated and integrated perspectives on environmental, economic, and social dimensions—An investigation of student views on sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 22, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, M.; Corney, G.; Childs, A. Student teachers’ conceptions of sustainable development: The starting-points of geographers and scientists. Educ. Res. 2004, 46, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsall, S. Measuring student teachers’ understandings and self-awareness of sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 814–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinç, A.; Aydin, A. Turkish Student Science Teachers’ Conceptions of Sustainable Development: A phenomenography. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 35, 731–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, C.; Gericke, N.; Höglund, H.O.; Bergman, E. Subject- and Experience-bound Differences in Teachers’ Conceptual Understanding of Sustainable Development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 526–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiropoulou, D.; Antonakaki, T.; Kontaxaki, S.; Bouras, S. Primary Teachers’ Literacy and Attitudes on Education for Sustainable Development. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2007, 16, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, C.; Gericke, N.; Höglund, H.-O.; Bergman, E. The barriers encountered by teachers implementing education for sustainable development: Discipline bound differences and teaching traditions. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2012, 30, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, A.; Sporre, K.; Ottander, C. Mapping What Young Students Understand and Value regarding the Issue of Sustainable Development. Int. Electron. J. Environ. Educ. 2013, 3, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Walshe, N. Understanding students’ conceptions of sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 537–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Emotional Awareness: On the Importance of Including Emotional Aspects in Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 7, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, S.; Scott, W. Higher Education and Sustainable Development: Paradox and Possibility; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.J. Epilogue: Creating networks of conversations. In Social Learning towards a Sustainable World: Principles, Perspectives and Praxis; Wals, A.E.J., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 497–506. [Google Scholar]

- Rudsberg, K.; Öhman, J. Pluralism in practice—Experiences from Swedish evaluation, school development and research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.B.; Schnack, K. The Action Competence Approach in Environmental Education. Environ. Educ. Res. 1997, 3, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiting, S. Issues for environmental education and ESD research development: Looking ahead from WEEC 2007 in Durban. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóhannesson, I.Á.; Norðdahl, K.; Óskarsdóttir, G.; Pálsdóttir, A.; Pétursdóttir, B. Curriculum analysis and education for sustainable development in Iceland. Environ. Educ. Res. 2011, 17, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, F. School initiatives related to environmental change—Development of action competence. In Research in Environmental and Health Education; Jensen, B.B., Ed.; Forskningscenter for Miljø-og Sundhedsundervisning, Danmarks Lærerhøjskol: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1995; pp. 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hasslof, H.; Malmberg, C. Critical Thinking as Room for Subjectification in Education for Sustainable Development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harness, H.; Drossman, H. The environmental education through filmmaking project. Environ. Educ. Res. 2011, 17, 829–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Losada, M.; Vega-Marcote, P.; Pérez-Rodríguez, U.; Álvarez-Lires, M. Going to action? A literature review on educational proposals in formal Environmental Education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 390–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincheloe, J.L. Knowledge and Critical Pedagogy: An Introduction; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Uzzell, D.; Räthzel, N. Transforming environmental psychology. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotti, V. Soft versus critical global citizenship education. Policy Pract. Dev. Educ. Rev. 2006, 3, 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Van Poeck, K.; Vandenabeele, J. Education as a response to sustainability issues. Eur. J. Res. Educ. Learn. Adults 2014, 5, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englund, T.; Öhman, J.; Östman, L. Deliberative Communication for Sustainability? A Habermas-Inspired Pluralistic Approach. In Sustainability and Security within Liberal Societies; Gough, S., Stables, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Englund, T. Deliberative communication: A pragmatist proposal. J. Curric. Stud. 2006, 38, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.R. Civil Passions: Moral Sentiments and Democratic Deliberation; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsall, S. Empowering Students to Act: Learning About, Through and From the Nature of Action. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 26, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fien, J. Learning to care: A focus for values in health and environmental education. Health Educ. Res. 1997, 12, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E. Between knowing what is right and knowing that is it wrong to tell others what is right: On relativism, uncertainty and democracy in environmental and sustainability education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. High. Educ. 1996, 32, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijsmans, D.M.A.; Prins, F.J.; Martens, R.L. The Design of Competency-Based Performance Assessment in E-Learning. Learn. Environ. Res. 2006, 9, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyolo, O.E.K.; Karkaaien, S.; Keinonen, T. Implementing Education for Sustainable Development in Namibia: School Teachers’ Perceptions and Teaching Practices. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2018, 20, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egne, R.M. Representations of the Ethiopian multicultural society in secondary teacher education curricula. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2004, 16, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J.; Gupta, R.; Krasny, M.E. Practitioners’ perspectives on the purpose of environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 777–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Somerville, M. Sustainability education: Researching practice in primary schools. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimaryo, L.A. Åbo Akademi University Press; Åbo Akademi University Press: Åbo, Finland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sund, L. Facing global sustainability issues: Teachers’ experiences of their own practices in environmental and sustainability education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 788–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uitto, A.; Saloranta, S. Subject Teachers as Educators for Sustainability: A Survey Study. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.B.; Schnack, K. Assessing action competence? In Key Issues in Sustainable Development and Learning: A Critical Review; Gough, S., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004; pp. 164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, S.; Förster, R.; Zimmermann, A.B. Implementing Competence Orientation: Towards Constructively Aligned Education for Sustainable Development in University-Level Teaching-And-Learning. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M.; Mitcham, C. Exploring Qualitatively-Derived Concepts: Inductive—Deductive Pitfalls. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2002, 1, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, R.; Hopkins, C. EE ≠ ESD: Defusing the worry. Environ. Educ. Res. 2003, 9, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vowless, K. Education for the environment—What is it and how to do it. N. Z. J. Geogr. 2002, 113, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zint, M.; Kraemer, A.; Northway, H.; Lim, M. Evaluation of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s Conservation Education Programs. Conserv. Boil. 2002, 16, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. Human Nature and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 56, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D. Significant Life Experiences Revisited: A Review of Research on Sources of Environmental Sensitivity. Environ. Educ. Res. 1998, 29, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J. Action Research and Community Problem Solving: Environmental Education in an Inner-city. Educ. Action Res. 1994, 2, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colás-Bravo, P.; Magnoler, P.; Conde-Jiménez, J. Identification of Levels of Sustainable Consciousness of Teachers in Training through an E-Portfolio. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumler, M.L. Students of Action? A Comparative Investigation of Secondary Science and Social Studies Students’ Action Repertoires in a Land Use Context. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 42, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Harvard, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson, D. Looking to the Future: Building a Curriculum for Social Activism; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, G.T.; Stern, P.C. Environmental Problems and Human Behavior; Pearson Custom Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, S.; Fien, J.; Sykes, H.; Yencken, D. Young People and the Environment in Australia: Beliefs, Knowledge, Commitment and Educational Implications. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 1998, 14, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagell, U.; Almers, E.; Askerlund, P.; Apelqvist, M. What Kind of Actions are Appropriate? Eco-School Teachers’ and Instructors’ Ranking of Sustainability—Promoting Actions as Content in Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). Int. Electron. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 4, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasia, D. Environmental Education: Environment, Sustainability, Theoretical and Pedagogical Approaches; Epikentro: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Segalàs, J.; Ferrer-Balas, D.; Mulder, K. What do engineering students learn in sustainability courses? The effect of the pedagogical approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flogaitis, E. From Environmental Education to Education for Sustainable Development, Concerns, Trends, Recommendations; Nisos: Athens, Greece, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, W. Learning about Action, Learning from Action, Learning through Action. Clearing 1997, 99, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, B.B. Environmental and health education viewed from an action—Oriented perspective: A case from Denmark. J. Curric. Stud. 2004, 36, 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClaren, M.; Hammond, W. Integrating Education and Action in Environmental Action. In Environmental Education and Advocacy: Changing Perspectives of Ecology and Education; Johnson, E., Mappin, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 267–291. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, I.; Brockbank, A. The Action Learning Handbook; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kyburz-Graber, R. Environmental Education as Critical Education: How teachers and students handle the challenge. Camb. J. Educ. 1999, 29, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrecht, C.; Bruckermann, T.; Harms, U. Students’ Decision-Making in Education for Sustainability-Related Extracurricular Activities—A Systematic Review of Empirical Studies. Sustainability. 2018, 10, 3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Penguin: Munchen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, K. Deep learning and education for sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2003, 4, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S. Integrating sustainable development in TVET curriculum. In Proceedings of the 11th UNESCO-APEID International Conference on ‘Reinventing Higher Education: Toward Participatory and Sustainable Development’, Bangkok, Thailand, 12–14 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schelly, C.; Cross, J.E.; Franzen, W.; Hall, P.; Reeve, S. How to Go Green: Creating a Conservation Culture in a Public High School through Education, Modeling, and Communication. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 43, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shier, H. Pathways to participation: Openings, opportunities and obligations. Child. Soc. 2001, 15, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme in Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Uitto, A.; Pauw, J.B.-D.; Saloranta, S. Participatory school experiences as facilitators for adolescents’ ecological behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.J.; Van der Leij, T. Introduction. In Social Learning towards a Sustainable World: Principles, Perspectives and Praxis; Wals, A.E.J., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, U.E. How might Participation in Primary School Eco Clubs in England Contribute to Children’s Developing Action-Competence-Associated Attributes? Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bath, Bath, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.; Rodela, R. Social learning towards sustainability: Problematic, perspectives and promise. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2014, 69, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, G.; Posch, A. Higher education for sustainability by means of transdisciplinary case studies: An innovative approach for solving complex, real-world problems. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, K. Small groups’ ecological reasoning while making an environmental management decision. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2002, 39, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, J.; Angus, B. The Role of Civic Environmentalism in the Pursuit of Sustainable Communities. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2003, 46, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascopé, M.; Perasso, P.; Reiss, K. Systematic Review of Education for Sustainable Development at an Early Stage: Cornerstones and Pedagogical Approaches for Teacher Professional Development. Sustainablity 2018, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzell, D.L.; Davallon, J.; Jensen, B.B.; Gottensdiener, H.; Fontes, J.; Kofoed, J.; Uhrenholdt, G.; Vognsen, C. Children as Catalysts of Environmental Change; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Uzzell, D. Education for Environmental Action in the Community: New roles and relationships. Camb. J. Educ. 1999, 29, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stables, A.; Scott, W. The Quest for Holism in Education for Sustainable Development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimenäs, J.; Alexandersson, M. Crossing Disciplinary Borders: Perspectives on Learning About Sustainable Development. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2012, 14, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- UNECE. UNECE Strategy for Education for Sustainable Development. 2005. Available online: http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/documents/2005/cep/ac.13/cep.ac.13.2005.3.rev.1.e.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- NEEAC. Setting the Standard, Measuring Results, and Celebrating Successes: A Report to Congress on the Status of Environmental Education in the United States (EPA240-R-05-001); Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Hacking, E.B.; Barratt, R.; Scott, W. Engaging children: Research issues around participation and environmental learning. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisk, E.; Larson, K. Educating for Sustainability: Competences and Practices for Transformative Action. J. Sustain. Educ. 2011, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen, F.; Mayer, M. Comparative Study on Ecoschool Development Process; ENSI/SEED: Wien, Austria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Shaping the Future We Want. UN Decade of Escuation for Sustainable Development (2005–2014); Final Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton, D.R.E.; Warren, M.F.; Maiboroda, O.; Bailey, I. Sustainable development, higher education and pedagogy: A study of lecturers’ beliefs and attitudes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 579–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, J. Moral Perspectives in Selective Traditions of Environmental Education. In Learning to Change Our World; Wickenburg, P., Axelsson, A., Fritzén, L., Helldén, G., Öhman, J., Eds.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2004; pp. 33–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sund, P. Experienced ESD-schoolteachers’ teaching—An issue of complexity. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 21, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K. Starting the pluralistic tradition of teaching? Effects of education for sustainable development (ESD) on pre-service teachers’ views on teaching about sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corney, G. Education for Sustainable Development: An Empirical Study of the Tensions and Challenges Faced by Geography Student Teachers. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2006, 15, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulton, C.; Day, V.; Grace, M. Controversial issues—Teachers’ attitudes and practices in the context of citizenship education. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2004, 30, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.; Whitehouse, H.; Gooch, M. Barriers, Successes and Enabling Practices of Education for Sustainability in Far North Queensland Schools: A Case Study. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 43, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennelly, J.; Taylor, N.; Maxwell, T.; Serow, P. Education for Sustainability and Pre-Service Teacher Education. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 28, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Per, S. Discerning Selective Traditions in the Socialization Content of Environmental Education: Implications for Education for Sustainable Development; Mälardalen University: Västerås, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.-H.; Anderson, R.C.; Nguyen-Jahiel, K.; Archodidou, A. Discourse Patterns During Children’s Collaborative Online Discussions. J. Learn. Sci. 2007, 16, 333–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Woo, H.L. Comparing asynchronous online discussions and face-to-face discussions in a classroom setting. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2007, 38, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiller, J.; Durndell, A.; Ross, A. Peer Interaction and Critical Thinking: Face-to- Face or Online Discussion? Learn. Inst. 2018, 18, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallert, D.L.; Chiang, Y.-H.V.; Park, Y.; Jordan, M.E.; Lee, H.; Cheng, A.-C.J.; Chu, H.-N.R.; Lee, S.; Kim, T.; Song, K. Being polite while fulfilling different discourse functions in online classroom discussions. Comput. Educ. 2009, 53, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckle, J. Education for Sustainable Development: A Briefing Paper for the Training and Development Agency for School; Earthscan: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ketlhoilwe, M.J. Genesis of Environmental Education Policy in Botswana: Construction and Interpretation; Rhodes University: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Sustainable Education: Re-Visioning Learning and Change; Green Books: Dartington, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jabareen, Y. Towards a Sustainability Education Framework: Challenges, Concepts and Strategies—The Contribution from Urban Planning Perspectives. Sustainability 2012, 4, 2247–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, P.; Bradbury, H. Introduction: Inquiry and Participation in Search of a world Worthy of Human Aspiration. In Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice; Reason, P., Bradbury, H., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sinakou, E.; Pauw, J.B.-D.; Goossens, M.; Van Petegem, P. Academics in the field of Education for Sustainable Development: Their conceptions of sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participation | It encourages the participation of students, which includes from formulation of questions or making suggestions to decision-making in solving the problems or in the process of teaching and learning, where students are involved actively, they express their opinions and take part in the decision-making, individually and collectively, in the process. |

| Involvement of the student body | It arises from students’ needs and concerns, aiming to connect with their interest. |

| Social learning | It uses learning in groups and cooperating teams. |

| Real issues | It practices relations with the real world (through real experiences, hands-on learning, outdoors, etc.). |

| Interdisciplinary perspective | Issues are dealt from different inter-connected disciplines. |

| Complexity | It is based on the culture of complexity, that is, students tackle their own understanding of problems/complex situations and look for relationships, interactions, different points of view and consider possible actions. |

| Criticalthinking | It encourages critical analysis through different perspectives, reflecting on conflicts of interest. This approach can range from the critical handling of information to the analysis of the complexity of situations and be aware of their role in society. |

| Actions | They deal explicitly with the study of possible actions/solutions targeted at effecting real change regarding the environment, the analysis of student lifestyles, behaviour, decision-making and actions. |

| Community | It involves the community, different members of the educational community (not just the students), or even groups outside the educational community, and uses an approach based on social change. |

| Source: Varela-Losada et al. (2016) [47] | |

|

| Journals | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| Environmental Education Research | 11 |

| Sustainability | 5 |

| The Journal of Environmental Education | 4 |

| Journal of Environmental Psychology. | 3 |

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 2 |

| Cambridge Journal of Education | 2 |

| Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability | 2 |

| Australian Journal of Environmental Education | 2 |

| Educational Researcher | 1 |

| Development Education Policy and Practice | 1 |

| Research in Science and Technological Education | 1 |

| Research in Environmental and Health Education | 1 |

| Children and Society Volume | 1 |

| Clearing | 1 |

| Electronic Journal of Environmental Education | 1 |

| Journal of 1Curriculum Studies | 1 |

| Journal of Environmental Planning and Management | 1 |

| NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences | 1 |

| Books Publishers | |

| Routledge | 2 |

| Cambridge University Press | 2 |

| Springer | 1 |

| Sense Publishers: Rotterdam/Boston/Taipei | 1 |

| Pearson Custom Publishing. | 1 |

| Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers | 1 |

| Lund: Studentlitteratur | 1 |

| Athens: Nisos | 1 |

| Brussels: International Academy of Education | 1 |

| Thessaloniki: Epikentro | 1 |

| Theses | |

| PhD thesis | 1 |

| Master thesis | 1 |

| Action-Oriented ESD Framework | Sources Used for the Framework of Varela- Losada et al a | Sources Used for the Action-Oriented ESD Framework b |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Action- taking | ||

| 1.1. Impact of action | Mogensen and Schnack 2010; UNECE 2005 [110]; NEEAC 2005 [111]; Wals 2007 | Jensen and Schnack, 1997; Hodson, 2011; Gardner and Stern, 2002; Jensen, 2002; Connell and colleagues, 1998; Stagel, Almers, Askerlund and Apelqvist, 2014; Colás-Bravo, Magnoler, Conde-Jiménez, 2018 |

| 1.2. Context of action | Mogensen and Schnack 2010; UNECE 2005; NEEAC 2005; Wals 2007 | Flogaitis, 2007; Dimitriou, 2009; Hammond 1997; Jensen 2004; McClaren and Hammond 2005; McGill and Brockbank, 2004; Kyburz- Graber, 1999 |

| 2. Students’ leadership in learning and teaching | Mogensen and Schnack 2010; Barratt-Hacking, Barratt and Scott 2007 [112] | Mogensen and Schnack 2010; Sandell et al., 2005; Schelly, Cross, Franzen, Hall and Reeve 2012; Shier 2001; UNESCO, 2014b; Uitto, Boeve-de Pauw and Saloranta, 2015; Garrecht, Bruckermann and Harms, 2018 |

| 3. Peer interaction | Frisk and Larson 2011 [113]; Wals 2007; Lave and Wenger 1991 | Lave and Wenger 1991; Wals 2007; Lee, 2014; Wals and Tore van der Leij, 2009; Wals and Rodela, 2014; Jensen and Schnack, 1997 |

| 4. Community involvement | Frisk and Larson 2011; Wals 2007; Hart 1992 | Lave and Wenger, 1991; Hogan 2002; Uzzell, Davallon, Jensen, Gottensdiener, Fontes, Kofoed, Uhrenholdt and Vognsen, 1994; Uzzell 1999; Green and Somerville 2014; Bascopé et al, 2018 |

| 5. Interdisciplinarity | Mogensenand Mayer 2005 [114]; Hungerford et al. 2003; Wals 2007; | Dimitriou, 2009; Walshe 2016; Borg, Gericke, Höglund and Bergman, 2012; Stables and Scott, 2002; Anyolo, Karkaaien and Keinonen, 2018; Dimenas and Alexandersson 2012; Wilhelm, Förster and Zimmermann, 2019 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sinakou, E.; Donche, V.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Van Petegem, P. Designing Powerful Learning Environments in Education for Sustainable Development: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215994

Sinakou E, Donche V, Boeve-de Pauw J, Van Petegem P. Designing Powerful Learning Environments in Education for Sustainable Development: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability. 2019; 11(21):5994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215994

Chicago/Turabian StyleSinakou, Eleni, Vincent Donche, Jelle Boeve-de Pauw, and Peter Van Petegem. 2019. "Designing Powerful Learning Environments in Education for Sustainable Development: A Conceptual Framework" Sustainability 11, no. 21: 5994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215994

APA StyleSinakou, E., Donche, V., Boeve-de Pauw, J., & Van Petegem, P. (2019). Designing Powerful Learning Environments in Education for Sustainable Development: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability, 11(21), 5994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215994