The Impact of the Quality of Interpersonal Relationships between Employees on Counterproductive Work Behavior: A Study of Employees in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

- to determine how the quality of interpersonal work relationships affects the extent of counterproductive work behavior,

- to determine whether the impact of interpersonal work relationship quality on the extent of counterproductive work behavior is moderated by employees’ demographic features (education, age, sex, length of service and type of work).

2. Quality of Interpersonal Relationships at Work

- the same relationships can be positive at some times and negative at others,

- they may include both positive and negative aspects (interactions),

- their intensity may change.

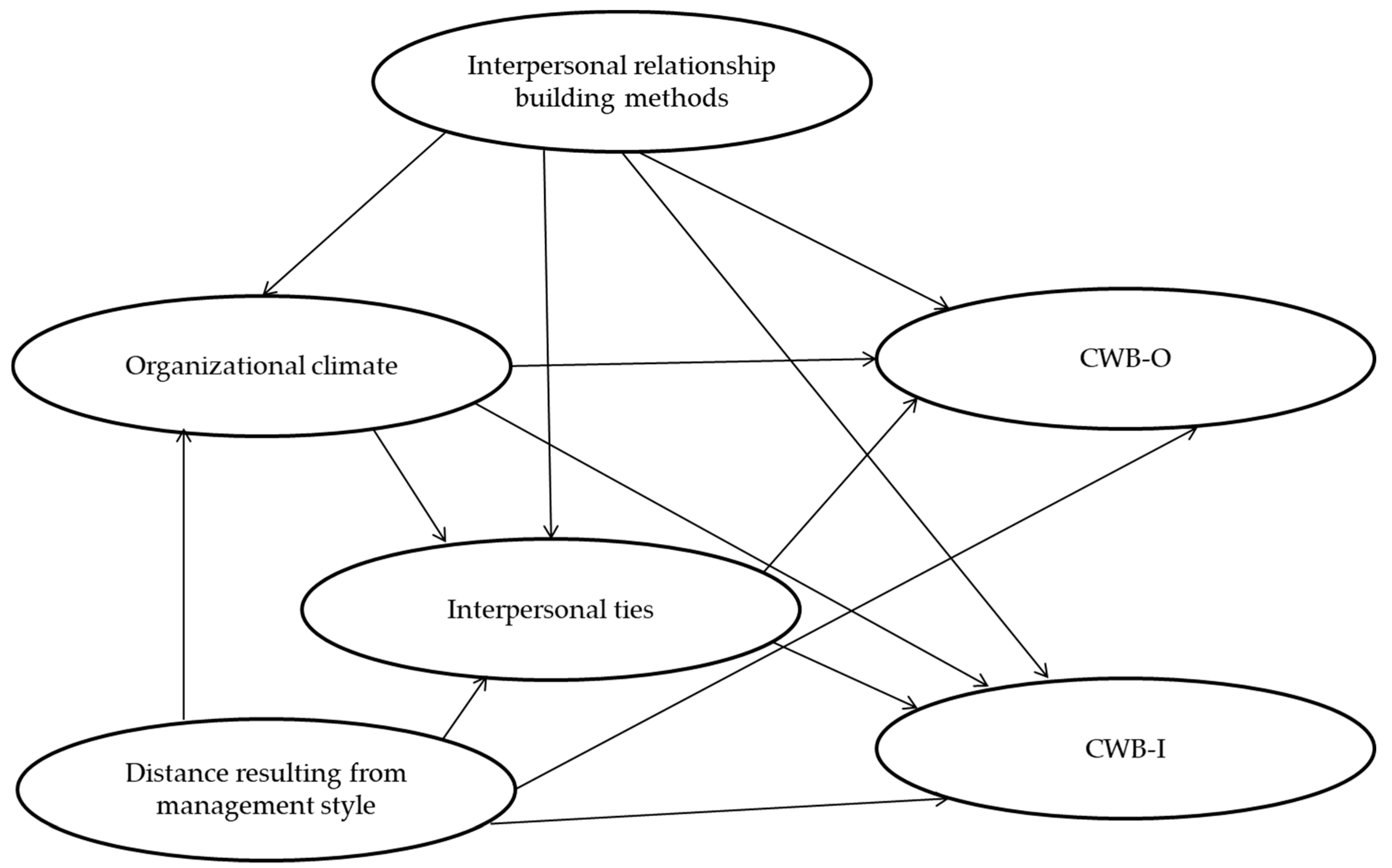

- organizational climate (e.g., atmosphere at work, honesty, trust, how parties treat one another),

- interpersonal ties (e.g., sharing personal information, contact after work, helping each other, celebrating important occasions together),

- interpersonal relationship building methods (e.g., caring for how the workplace is equipped, meetings with employees, surveying their opinions, the holding of company events),

- distance resulting from management style (e.g., fair treatment by the supervisor, the “human approach” of the boss, private contact after work).

3. Counterproductive Work Behavior

- it results in a violation of the standards in force in the organization,

- the conduct was engaged in voluntarily, and

- it harms (including potentially) the organization and/or its stakeholders.

- abuse against others—behavior harmful to other stakeholders of the organization (e.g., lying, gossiping, harassment),

- production deviance—performance of duties by the employee such that the work cannot be properly completed (in terms of quantity and/or quality of results),

- sabotage—deliberate destruction of the organization’s property (not only tangible but also intangible, e.g., its image),

- theft—intentional appropriation of property belonging to the organization or other people,

- withdrawal—limiting working time to below the minimum required to properly achieve the organization’s goals.

4. Methodology

4.1. Sampling Procedures and Participant Characteristics

- all municipal offices in Poland (fewer than 2500),

- the 200 businesses ranking as the 200 largest companies of 2017 by the Wprost weekly [83],

- 26 selected enterprises (from the Kujawsko-Pomorskie region—one of the 16 administrative regions of Poland), including 20 ranked among the 500 largest Polish businesses by the daily Rzeczpospolita for 2016 [84],

- the Faculty of Economic Sciences and Management at the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun (almost 3200 students—in the cover letter with the link to the questionnaire, it was mentioned that it should be completed only by professionally active people),

4.2. Measurement Scales

5. Results

5.1. Reliability Values

5.2. Hypothesis Testing

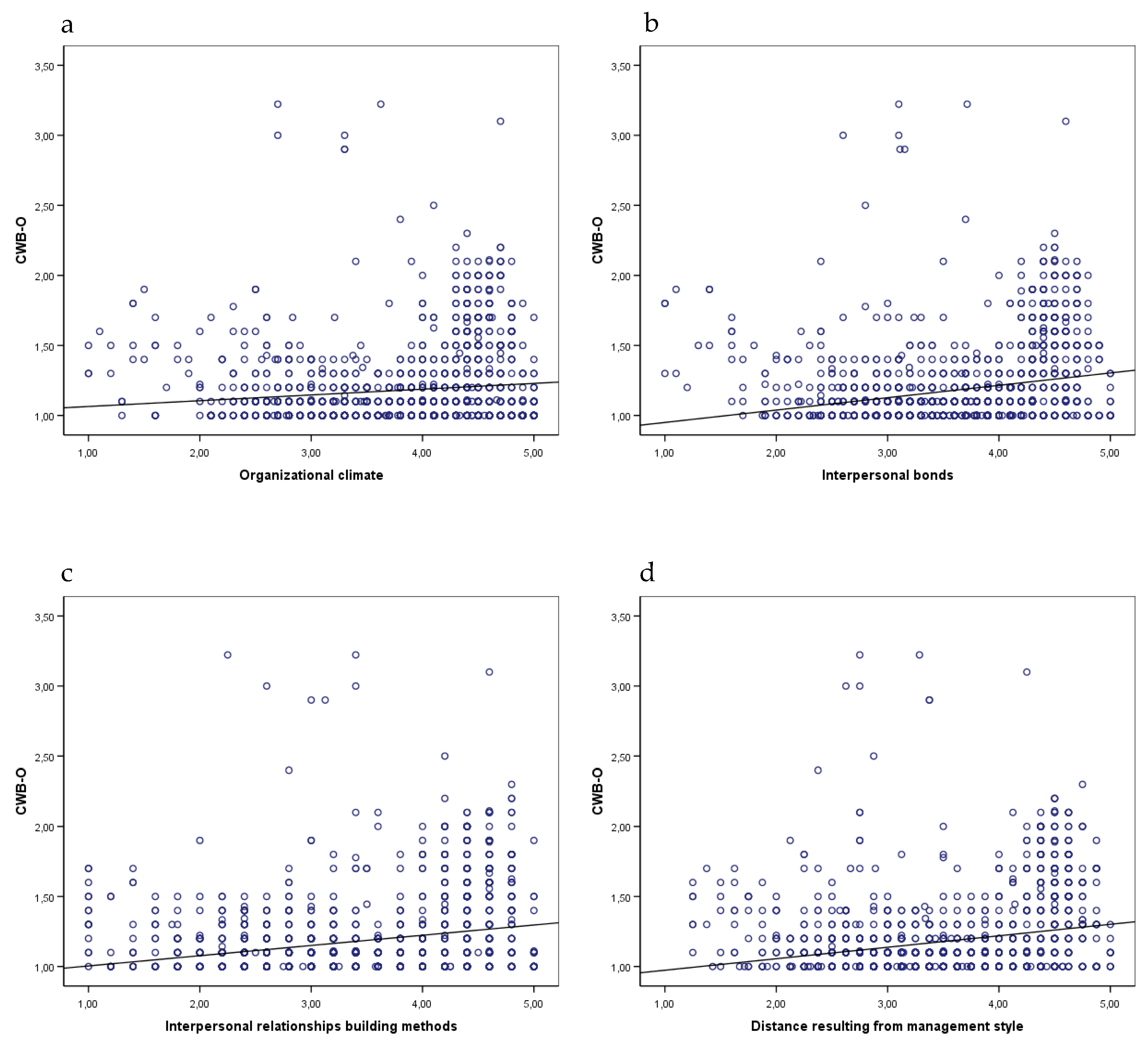

5.2.1. (H1): Quality of Interpersonal Relationships at Work Has a Negative Influence on the Degree of Counterproductive Work Behavior

- <0.05, good fit,

- 0.05–0.08, acceptable fit,

- 0.08–0.10, moderate fit,0.1, unacceptable fit [89].

5.2.2. (H2): The Impact of Interpersonal Work Relationship Quality on the Extent of Counterproductive Work Behavior is Moderated by Employees’ Demographic Features (Education, Age, Sex, Length of Service and Type of Work)

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions and Managerial Implications

- Building high-quality interpersonal relationships at work should be moderated so as not to reorient the employee away from the organization and towards him/herself or the team. Such a reorientation may result in a greater degree of CWB-O (e.g., in the name of solidarity with the team) or of CWB-I (e.g., abuse of colleagues’ trust).

- The organization must not forget that retaliation is one of the main reasons for employees to engage in counterproductive behavior against the employer. Hence, imprudent actions by managers (e.g., non-payment for overtime, undervaluing subordinates) may intensify such staff behavior.

- The organization’s prevailing climate (which should be based on honesty, solidarity, altruism, etc.) is very important for the quality of relationships at work, and thus for employees’ propensity for CWB.

- Of equal importance for the relationship between quality of relationships and CWB are employees’ demographic features. (The relationship is strongest for employees with higher education, those in senior positions, those with longer service, and women. Apart from these, only a few significant differences in the influence of relationship quality on CWB were found between age groups.)

- When recruiting new people, attention should be paid not only to candidates’ knowledge, experience and qualifications, but also to their propensity for CWB, as well as to the impact of a given person on the quality of relationships in the team (in this case, integrity tests or information from former employers or from Facebook can be used).

- The process of socializing employees within the organization should be thought out and balanced in terms of orientating the person towards his/her own interest, and that of the team and the workplace. Open communication and consistency in action play an important role here.

- Employees should be trained in the competences that play a key role in the quality of interpersonal relationships at work and in counterproductive work behavior. These might include not only traditional training, but also atypical activities (e.g., strategy games, going out to play paint ball together).

- The quality of relationships between employees and the degree of CWB should constantly be monitored so as to respond sufficiently early to any disturbing situations. The available measuring scales can be used for this (e.g., those discussed in the article—the CWB-C and the QIRT-S). It is necessary to ensure respondent anonymity, which will increase data reliability. Naturally, after completing a survey, employees should be informed of their results, and the necessary actions should be taken to mold the quality of relationships between employees and to prevent CWB.

6.2. Limitations and Future Study Directions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| How often have you done each of the following things on your present job? (1—never, 2—one or two times, 3—one or two times per month, 4—one or two times per week, 5—every day) | Dimensions of CWB | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | O | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | X | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| To what extent do you think the following statements apply to the work team you belong to? (please respond to each) | Strongly disagree | Somewhat disagree | Hard to say | Somewhat agree | Strongly agree |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

References

- Allen, T.D.; de Tormes Eby, L.T. The Study of Interpersonal Relationships: An Introduction. In Personal Relationships. The Effect on Employee Attitudes, Behavior, and Well-being; de Tormes Eby, L.T., Allen, T.D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J.E. Build High Quality Connections. In How to Be a Positive Leader: Small Actions, Big Impacts; Spreitzer, G., Dutton, J.E., Eds.; Berrett–Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bono, J.E.; Yoon, D.J. Positive Supervisory Relationships. In Personal Relationships. The Effect on Employee Attitudes, Behavior, and Well-Being; de Tormes Eby, L.T., Allen, T.D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A.; Gittel, J.H. High-quality relationships, psychological safety, and learning from failures in work organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 709–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilchert, S. Counterproductive sustainability behaviors and their relationship to personality traits. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2018, 26, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glińska-Neweś, A. Pozytywne Relacje Interpersonalne w Zarządzaniu; Wydawnictwo UMK: Toruń, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B. Positive Coworker Exchanges. In Personal Relationships. The Effect on Employee Attitudes, Behavior, and Well-being; de Tormes Eby, L.T., Allen, T.D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 107–130. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee Green Behavior: A Theoretical Framework, Multilevel Review, and Future Research Agenda. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrat-Guillard, D.; Glińska-Neweś, A. I Respect You and I Help You: Links Between Positive Relationships at Work and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour. J. Posit. Manag. 2014, 5, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M. Personality, Affect, and Behavior in Groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdar, D.; Van Dyne, L. The Joint Effects of Personality and Workplace Social Exchange Relationships in Predicting Task Performance and Citizenship Performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1286–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, R.S. A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Counterproductive Work Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1241–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Diefendorff, J.M. The Relations of Daily Counterproductive Workplace Behavior with Emotions, Situational Antecedents, and Personality Moderators: A Diary Study in Hong Kong. Pers. Psychol. 2009, 62, 259–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Nangia Sharma, P. Bringing Together the Yin and Yang of Social Exchanges in Teams. In Personal Relationships. The Effect on Employee Attitudes, Behavior, and Well-being; De Tormes Eby, L.T., Allen, T.D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- De Tormes Eby, L.T.; Allen, T.D. Preface. In Personal Relationships. The Effect on Employee Attitudes, Behavior, and Well-being; De Tormes Eby, L.T., Allen, T.D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. XVII–XIX. [Google Scholar]

- Brass, D.J.; Butterfield, K.D.; Skaggs, B.C. Relationships and Unethical Behavior: A Social Network Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschan, F.; Semmer, N.; Inversin, L. Work Related and “Private” Social Interactions at Work. Soc. Indic. Res. 2004, 67, 145–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlicki, D.P.; Folger, R. Retaliation in the workplace: The roles of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.M. From Proving to Becoming: How Positive Relationships Create a Context for Self-Discovery and Self-Actualization. In Exploring Positive Relationships at Work. Building a Theoretical and Research Foundation; Dutton, J.E., Ragins, B.R., Eds.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Harrison, D.A. Do peers make the place? Conceptual synthesis and meta-analysis of coworker effects on perceptions, attitudes, OCBs, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1082–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragins, B.R.; Verbos, A.K. Positive Relationships in Action: Relational Mentoring and Mentoring Schemas in the Workplace. In Exploring Positive Relationships at Work. Building a Theoretical and Research Foundation; Dutton, J.E., Ragins, B.R., Eds.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lamm, E.; Tosti-Kharas, J.; Williams, E.G. Read This Article, but Don’t Print It: Organizational Citizenship Behavior Toward the Environment. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 163–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, A.E.; Bono, J.E.; Purvanova, R.K. Flourishing Via Workplace Relationships: Moving Beyond Instrumental Support. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1199–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, M.; Brass, D.J. Relational Correlates of Interpersonal Citizenship Behavior: A Social Network Perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikola-Norrbacka, A.S.R. Trust, good governance and unethical actions in Finnish public administration. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2010, 23, 647–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everton, W.J.; Jolton, J.A.; Mastrangelo, P.M. Be nice and fair or else: Understanding reasons for employees’ deviant behaviors. J. Manag. Dev. 2007, 26, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L.; Bennett, R.J. A Typology of Deviant Workplace Behaviors: A Multidimensional Scaling Study. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galperin, B.L.; Burke, R.J. Uncovering the relationship between workaholism and workplace destructive and constructive deviance: An exploratory study. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 17, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2018).

- Hopwood, B.; Mellor, M.; O’Brien, G. Sustainable Development: Mapping Different Approaches. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 13, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainela, T. Types and functions of social relationships in the organizing of an international joint venture. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, K.A.; Jonsen, K.; Rispens, S. Relationships at Work: Intragroup Conflict and the Continuation of Task and Social Relationships in Workgroups. Curr. Top. Manag. 2014, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- LePine, J.A.; Methot, J.R.; Crawford, E.R.; Buckman, B.R. A Model of Positive Relationships in Team: The Role of Instrumental, Friendship, and Multiplex Social Network Ties. In Personal Relationships. The Effect on Employee Attitudes, Behavior, and Well-being; De Tormes Eby, L.T., Allen, T.D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarro, J.J. The Development of Working Relationships. In Intellectual Teamwork. Social and Technological Foundations Cooperative Work; Galegher, J., Kraut, R.E., Egido, C., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1990; pp. 79–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hinde, R.A. Relationships: A Dialectical Perspective; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McCauley, C.D. Reflection on Integration: Supervisor–Employee Relationships. In Personal Relationships. The Effect on Employee Attitudes, Behavior, and Well-being; De Tormes Eby, L.T., Allen, T.D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Laschober, T.C.; Allen, T.D.; De Tormes Eby, L.T. Negative Nonwork Relational Exchanges and Links to Employees’ Work Attitudes, Work Behaviors, and Well-being. In Personal Relationships. The Effect on Employee Attitudes, Behavior, and Well-being; De Tormes Eby, L.T., Allen, T.D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 325–348. [Google Scholar]

- Heaphy, E.D. Bodily Insights: Three Lenses on Positive Organizational Relationships. In Exploring Positive Relationships at Work. Building a Theoretical and Research Foundation; Dutton, J.E., Ragins, B.R., Eds.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Holliday, W.J. Integrating Positive and Negative Nonwork Relational Exchanges: Similarities, Differences, and Future Directions. In Personal Relationships. The Effect on Employee Attitudes, Behavior, and Well-being; De Tormes Eby, L.T., Allen, T.D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 349–363. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, E.W. Energizing Others in Work Connections. In Exploring Positive Relationships at Work. Building a Theoretical and Research Foundation; Dutton, J.E., Ragins, B.R., Eds.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ragins, B.R.; Dutton, J.E. Positive Relationships at Work: An Introduction and Invitation. In Exploring Positive Relationships at Work. Building a Theoretical and Research Foundation; Dutton, J.E., Ragins, B.R., Eds.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B.; Lundby, K. Service Relationships: Nuances and Contingencies. In Personal Relationships. The Effect on Employee Attitudes, Behavior, and Well-being; De Tormes Eby, L.T., Allen, T.D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 287–300. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, K. Paradox in Positive Organizational Change. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2008, 44, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.; Schmitz, A.; Di Fabio, A.; Daellenbach, U. The Role of Relationships at Work and Happiness: A Moderated Mediation Study of New Zealand Managers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudé, P.; Buttle, F. Assessing Relationship Quality. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2000, 29, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, D.H.; Sandberg, W.R. Friendship Within Entrepreneurial Teams and its Association with Team and Venture Performance. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2000, 25, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaphy, E.D.; Dutton, J.E. Positive Social Interactions and the Human Body at Work: Linking Organizations and Physiology. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szostek, D.; Glińska-Neweś, A. Identyfikacja wymiarów jakości relacji interpersonalnych w organizacji. Organizacja i Kierowanie 2017, 3, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E. Negative and Positive Coworker Exchanges: An Integration. In Personal Relationships. The Effect on Employee Attitudes, Behavior, and Well-being; De Tormes Eby, L.T., Allen, T.D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- Atrek, B.; Marcone, M.R.; Gregori, G.L.; Temperini, V.; Moscatelli, L. Relationship Quality in Supply Chain Management: A Dyad Perspective. Ege Acad. Rev. 2014, 14, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarmeas, D.; Zeriti, A.; Baltas, G. Relationship Value: Drivers and Outcomes in International Marketing Channels. J. Int. Mark. 2016, 24, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storbacka, K.; Strandvik, T.; Grönroos, C. Managing Customer Relationships for Profit: The Dynamics of Relationship Quality. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1994, 5, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The Strength of Weak Ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherony, K.M.; Green, S.G. Coworker Exchange: Relationships between Coworkers, Leader–Member Exchange, and Work Attitudes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinn, K.L. History, Structure, and Practices: San Pedro Longshoremen in the Face of Change. In Exploring Positive Relationships at Work. Building a Theoretical and Research Foundation; Dutton, J.E., Ragins, B.R., Eds.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Tepper, B.J.; Almeda, M. Negative Exchanges with Supervisors. In Personal Relationships. The Effect on Employee Attitudes, Behavior, and Well-Being; De Tormes Eby, L.T., Allen, T.D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 67–93. [Google Scholar]

- Szostek, D. Kontrproduktywne Zachowania Organizacyjne w Kontekście Jakości Relacji Interpersonalnych w Zespołach Pracowniczych; Wydawnictwo Naukowe UMK: Toruń, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ariño, A.; De la Torre, J.; Ring, P.S. Relational Quality: A Dynamic Framework for Assessing the Role of Trust in Strategic Alliances; IESE Research Paper No. 389; IESE: Barcelona, Spain, 1999; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J.E.; Heaphy, E. The Power of High Quality Connections. In Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett–Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 263–278. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J.E. Fostering high quality connections through respectful engagement. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2003, 1, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzhausen, L.; Fourie, L. Employees’ perceptions of company values and objectives and employer–employee relationships: A theoretical model. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2009, 14, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, L.C.; Grunig, J.E. Guidelines for Measuring Relationships in Public Relations, Institute for Public Relations. 1999, pp. 1–40. Available online: http://www.instituteforpr.org/wp-content/uploads/Guidelines_Measuring_Relationships.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2019).

- Palmatier, R.W.; Dant, R.P.; Grewal, D.; Evans, K.R. Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of Relationship Marketing: A Meta-Analysis. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerdinger, F.W. Formen des Arbeitsverhaltens. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225270532_Formen_des_Arbeitsverhaltens (accessed on 4 February 2019).

- Parks, L.; Mount, M.K. The “Dark Side” of Self-Monitoring: Engaging in Counterproductive Behaviors at Work. Acad. Manag. Best Conf. Pap. 2005, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E.; Phillips, B. Measuring Workaholism: Content Validity of the Work Addiction Risk Test. Psychol. Rep. 1995, 77, 657–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.; Spector, P.E.; Miles, D. Counterproductive Work Behavior (CWB) in Response to Job Stressors and Organizational Justice: Some Mediator and Moderator Tests for Autonomy and Emotions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 59, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruys, M.L.; Sackett, P.R. Investigating the Dimensionality of Counterproductive Work Behavior. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2003, 11, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Fox, S.; Penney, L.M.; Bruursema, K.; Goh, A.; Kessler, S. The dimensionality of counterproductivity: Are all counterproductive behaviors created equal? J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, M.A.; Parvez, A. Counterproductive Behavior at Work: A Comparison of Blue Collar and White Collar Workers. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2013, 7, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Thakur, K. Counterproductive Work Behaviour: The Role of Psychological Contract Violation. Int. J. Multidiscip. Approach Stud. 2016, 3, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E.; Fox, S. Counterproductive Work Behavior and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Are They Opposite Forms of Active Behavior? Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2010, 59, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangione, T.W.; Quinn, R.P. Job satisfaction, counterproductive behavior, and drug use at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 60, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, H.N. Punishment theory and industrial discipline. Ind. Relat. 1976, 15, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinger, R.C.; Clark, J.P. Formal and informal social controls of employee deviance. Sociol. Q. 1982, 23, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardi, Y.; Weitz, E. Misbehavior in Organizations; Lawrence Elbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Godkin, L. Mid-Management, Employee Engagement, and the Generation of Reliable Sustainable Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temminck, E.; Mearns, K.; Fruhen, L. Motivating Employees towards Sustainable Behaviour. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyak-Hai, L.; Tziner, A. Relationships between counterproductive work behavior, perceived justice and climate, occupational status, and leader-member exchange. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2014, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, L.M.; Hunter, E.M.; Perry, S.J. Personality and counterproductive work behaviour: Using conservation of resources theory to narrow the profile of deviant employees. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, P.; Sambasivan, M.; Kumar, N. Counterproductive work behavior among frontline government employees: Role of personality, emotional intelligence, affectivity, emotional labor, and emotional exhaustion. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2016, 32, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.; Hur, W.-M.; Kim, M.; Kang, S. Hidden Roles of CSR: Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility as a Preventive against Counterproductive Work Behaviors. Sustainability 2017, 9, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wprost. Ranking 200 Największych Polskich Firm. 2017. Available online: http://rankingi.wprost.pl/200-najwiekszych-firm#pelna-lista (accessed on 16 January 2018).

- Rzeczpospolita. Lista 500–Edycja. 2016. Available online: https://sklep.rp.pl/produkt/lista_500__edycja_2015.php (accessed on 16 January 2018).

- Spector, P.E. Counterproductive Work Behavior Checklist (CWB-C). Available online: http://shell.cas.usf.edu/~pspector/scales/cwbcpage.html (accessed on 30 January 2018).

- Derevianko, O. Reputation stability vs anti-crisis sustainability: Under what Circumstances will Innovations, Media Activities and CSR be in Higher Demand? Oeconomia Copernic. 2019, 10, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilelienė, L.; Grigaliūnaitė, V. Colour temperature in advertising and its impact on consumer purchase intentions. Oeconomia Copernic. 2017, 8, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żurek, M. Inklinacje Behawioralne na Rynkach Kapitałowych w Świetle Modeli SEM; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika: Toruń, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bedyńska, S.; Książek, M. Statystyczny Drogowskaz 3. Praktyczny Przewodnik Wykorzystania Modeli Regresji Oraz Równań Strukturalnych; Wydawnictwo Akademickie Sedno: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, B.; Wuensch, K.L. SPSS and SAS programs for comparing Pearson correlations and OLS regression coefficients. Behav. Res. Methods 2013, 45, 880–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | Concept |

|---|---|

| [52] | Relationship quality is identified with its strength and means the existence of links between the parties that lead to satisfaction and commitment. In turn, the strength of a relationship is “a (probably linear) combination of the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy (mutual confiding), and the reciprocal services which characterize the tie” [53] (p. 1361). |

| [54] | Relationship quality is the level of mutual respect, trust and sense of duty between employees. |

| [55] (p. 265) | “Quality of relationship entails a pervasive, intentional, and constructive focus on mutual support and on members as individuals.” |

| [50] | Relationship quality is an evaluation of how well a relationship meets the parties’ expectations, needs, predictions, goals and aspirations. |

| [56] | Relationship quality is an evaluation of how far a relationship is based on the principles of reciprocity. |

| [36] | Relationship quality is an evaluation of what actions the parties take towards each other, their feelings and attitudes, and the results that the relationship brings them. |

| [6] | High-quality relationships are “relationships built on the interpersonal closeness of employees, as expressed in mutual interest, kindness and willingness to cooperate, contributing to creating a positive organizational climate conducive to effective communication, trust, loyalty and commitment to work”. |

| Source | Definition |

|---|---|

| [67] (p. 292) | “Behaviors [that] are harmful to the organization by directly affecting its functioning or property, or by hurting employees in a way that will reduce their effectiveness.” |

| [68] (p. 30) | “Any intentional behavior on the part of an organization member viewed by the organization as contrary to its legitimate interest.” |

| [69] (p. 447) | “Set of distinct acts that share the characteristics that they are volitional (as opposed to accidental or mandated) and harm or intend to harm organizations and/or organization stakeholders, such as clients, coworkers, customers, and supervisors.” |

| [70] (p. 418–419) | “Set of negative behaviors that are destructive to the organization by disturbing its operational activities or assets, or by hurting workers in such a way that will overcome their efficiency.” |

| [71] (p. 14) | “Problem that violates significant organizational norms and threatens the wellbeing of an organization, its members, or both.” |

| Source. | Classification | |

|---|---|---|

| [73] |

| |

| [74] |

| |

| [75] |

| |

| [27] |

| |

| [68] |

|

|

| [76] |

| |

| Sex | F | 56.8% (844 persons) |

| M | 41.7% (620 persons) | |

| n/a | 1.6% (24 persons) | |

| Age | mean | 40.4 years |

| min. | 18 years | |

| max. | 67 years | |

| SD | 11.9 years | |

| n/a | 70 persons | |

| Education | higher | 55.1% (820 persons) |

| secondary | 22.1% (329 persons) | |

| vocational | 20.9% (311 persons) | |

| middle school | 0.3% (4 persons) | |

| none | 0.3% (4 persons) | |

| n/a | 1.3% (20 persons) | |

| Length of service in current position | mean | 9.5 years |

| min. | 1 month | |

| max. | 48 years | |

| SD | 9.8 years | |

| n/a | 84 persons | |

| Current type of work | office/clerical | 49.2% (731 persons) |

| management | 27.4% (407 persons) | |

| blue collar | 21.7% (323 persons) | |

| n/a | 1.8% (27 persons) | |

| Sector of current employ | private | 53.2% (791 persons) |

| public | 46.6% (693 persons) | |

| n/a | 0.3% (4 persons) |

| Item No. | Item | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | Purposely damaged a piece of equipment or property | 1447 | 97.2 |

| 25 | Took money from your employer without permission | 1462 | 98.3 |

| 32 | Stole something belonging to someone at work | 1460 | 98.1 |

| 35 | Threatened someone at work with violence | 1421 | 95.5 |

| 36 | Threatened someone at work, but not physically | 1425 | 95.8 |

| 41 | Destroyed property belonging to someone at work | 1455 | 97.8 |

| 43 | Hit or pushed someone at work | 1418 | 95.3 |

| Factor | Measurable Variable | Factor Loading | % of Variance | % of Cumulative Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational climate | Q25 | 0.93 | 51.89 | 51.89 |

| Q27 | 0.711 | 7.15 | 59.04 | |

| Q29 | 0.678 | 6.84 | 65.88 | |

| Q30 | 0.670 | 5.89 | 71.77 | |

| Q35 | 0.661 | 5.83 | 77.59 | |

| Q38 | 0.684 | 5.17 | 82.77 | |

| Q50 | 0.692 | 4.96 | 87.73 | |

| Q51 | 0.693 | 4.55 | 92.28 | |

| Q52 | 0.662 | 4.17 | 96.44 | |

| Q58 | 0.677 | 3.56 | 100.00 | |

| Interpersonal ties | Q2 | 0.621 | 42.50 | 42.50 |

| Q3 | 0.582 | 8.53 | 51.03 | |

| Q4 | 0.621 | 7.76 | 58.79 | |

| Q6 | 0.599 | 7.04 | 65.83 | |

| Q7 | 0.580 | 6.56 | 72.38 | |

| Q9 | 0.603 | 6.24 | 78.62 | |

| Q10 | 0.622 | 5.82 | 84.44 | |

| Q11 | 0.573 | 5.53 | 89.97 | |

| Q13 | 0.619 | 5.21 | 95.18 | |

| Q16 | 0.587 | 4.82 | 100.00 | |

| Distance resulting from management style | Q17 | 0.645 | 42.84 | 42.84 |

| Q18 | 0.665 | 11.53 | 54.37 | |

| Q20 | 0.612 | 10.09 | 64.46 | |

| Q21 | 0.739 | 8.66 | 73.12 | |

| Q22 | 0.474 | 7.75 | 80.87 | |

| Q23 | 0.501 | 7.00 | 87.87 | |

| Q28 | 0.596 | 6.30 | 94.17 | |

| Q46 | 0.447 | 5.83 | 100.00 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods | Q39 | 0.629 | 51.35 | 51.35 |

| Q40 | 0.677 | 15.65 | 67.00 | |

| Q41 | 0.667 | 12.32 | 79.32 | |

| Q42 | 0.559 | 11.12 | 90.44 | |

| Q43 | 0.596 | 9.56 | 100.00 | |

| Individual-oriented CWB (CWB-I) | C26 | 0.780 | 57.02 | 57.02 |

| C27 | 0.829 | 10.89 | 67.91 | |

| C28 | 0.660 | 7.24 | 75.15 | |

| C29 | 0.791 | 6.47 | 81.62 | |

| C30 | 0.845 | 4.21 | 85.83 | |

| C31 | 0.682 | 4.13 | 89.96 | |

| C33 | 0.727 | 2.97 | 92.93 | |

| C34 | 0.742 | 2.71 | 95.64 | |

| C37 | 0.552 | 2.31 | 97.94 | |

| C38 | 0.630 | 2.06 | 100.00 | |

| Organization-oriented CWB (CWB-O) | C1 | 0.504 | 28.57 | 28.57 |

| C5 | 0.767 | 12.53 | 41.10 | |

| C7 | 0.442 | 11.06 | 52.16 | |

| C8 | 0.370 | 9.24 | 61.40 | |

| C9 | 0.515 | 8.01 | 69.43 | |

| C13 | 0.358 | 7.59 | 77.01 | |

| C15 | 0.452 | 6.98 | 84.00 | |

| C16 | 0.382 | 6.37 | 90.37 | |

| C19 | 0.431 | 5.41 | 95.78 | |

| C24 | 0.423 | 4.22 | 100.000 |

| Factor (Relationship Quality Category, Counterproductive Behavior Dimension) | Measurable Variables | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational climate | Q25, Q27, Q29, Q30, Q35, Q38, Q50, Q51, Q52, Q58 | 0.897 |

| Interpersonal ties | Q2, Q3, Q4, Q6, Q7, Q9, Q10, Q11, Q13, Q16 | 0.849 |

| Distance resulting from management style | Q17, Q18, Q20, Q21, Q22, Q23, Q28, Q46 | 0.806 |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods | Q39, Q40, Q41, Q42, Q43 | 0.759 |

| CWB-I | C26, C27, C28, C29, C30, C31, C33, C34, C37, C38 | 0.914 |

| CWB-O | C1, C5, C7, C8, C9, C13, C15, C16, C19, C24 | 0.707 |

| Relationship | Parameter | Evaluation of Parameter | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q 25 ← Organizational climate | 0.654 | ||

| Q 27 ← Organizational climate | 0.670 | 0.000 | |

| Q 29 ← Organizational climate | 0.668 | 0.000 | |

| Q 30 ← Organizational climate | 0.635 | 0.000 | |

| Q 35 ← Organizational climate | 0.646 | 0.000 | |

| Q 38 ← Organizational climate | 0.653 | 0.000 | |

| Q 50 ← Organizational climate | 0.664 | 0.000 | |

| Q 51 ← Organizational climate | 0.664 | 0.000 | |

| Q 52 ← Organizational climate | 0.631 | 0.000 | |

| Q 58 ← Organizational climate | 0.631 | 0.000 | |

| Q 2 ← Interpersonal ties | 0.582 | 0.000 | |

| Q 3 ← Interpersonal ties | 0.541 | 0.000 | |

| Q 4 ← Interpersonal ties | 0.600 | 0.000 | |

| Q 6 ← Interpersonal ties | 0.560 | 0.000 | |

| Q 7 ← Interpersonal ties | 0.574 | 0.000 | |

| Q 9 ← Interpersonal ties | 0.573 | 0.000 | |

| Q 10 ← Interpersonal ties | 0.610 | 0.000 | |

| Q 11 ← Interpersonal ties | 0.545 | 0.000 | |

| Q 13 ← Interpersonal ties | 0.655 | 0.000 | |

| Q 16 ← Interpersonal ties | 0.560 | ||

| Q 39 ← Interpersonal relationship building methods | 0.661 | ||

| Q 40 ← Interpersonal relationship building methods | 0.694 | 0.000 | |

| Q 41 ← Interpersonal relationship building methods | 0.637 | 0.000 | |

| Q 42 ← Interpersonal relationship building methods | 0.546 | 0.000 | |

| Q 43 ← Interpersonal relationship building methods | 0.581 | 0.000 | |

| Q 17 ← Distance resulting from management style | 0.655 | ||

| Q 18 ← Distance resulting from management style | 0.669 | 0.000 | |

| Q 20 ← Distance resulting from management style | 0.623 | 0.000 | |

| Q 21 ← Distance resulting from management style | 0.730 | 0.000 | |

| Q 22 ← Distance resulting from management style | 0.461 | 0.000 | |

| Q 23 ← Distance resulting from management style | 0.487 | 0.000 | |

| Q 28 ← Distance resulting from management style | 0.603 | 0.000 | |

| Q 46 ← Distance resulting from management style | 0.463 | 0.000 | |

| C26 ← CWB-I | 0.792 | ||

| C27 ← CWB-I | 0.836 | 0.000 | |

| C28 ← CWB-I | 0.621 | 0.000 | |

| C29 ← CWB-I | 0.798 | 0.000 | |

| C30 ← CWB-I | 0.852 | 0.000 | |

| C31 ← CWB-I | 0.627 | 0.000 | |

| C33 ← CWB-I | 0.710 | 0.000 | |

| C34 ← CWB-I | 0.726 | 0.000 | |

| C37 ← CWB-I | 0.523 | 0.000 | |

| C38 ← CWB-I | 0.592 | 0.000 | |

| C1 ← CWB-I | 0.488 | ||

| C5 ← CWB-I | 0.546 | 0.000 | |

| C7 ← CWB-I | 0.439 | 0.000 | |

| C8 ← CWB-I | 0.391 | 0.000 | |

| C9 ← CWB-I | 0.542 | 0.000 | |

| C13 ← CWB-I | 0.402 | 0.000 | |

| C15 ← CWB-I | 0.504 | 0.000 | |

| C16 ← CWB-I | 0.423 | 0.000 | |

| C19 ← CWB-I | 0.411 | 0.000 | |

| C24 ← CWB-I | 0.471 | 0.000 |

| Relationship | Parameter | Evaluation of Parameter | Evaluation of Standardized Parameters | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Organizational climate | 0.234 | 0.244 | 0.000 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Organizational climate | 0.630 | 0.705 | 0.000 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Interpersonal ties | 0.200 | 0.267 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Interpersonal ties | −0.028 | −0.034 | 0.145 | |

| Organizational climate → Interpersonal ties | 0.556 | 0.663 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-O | 0.101 | 0.312 | 0.000 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-O | −0.182 | −0.537 | 0.000 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-O | 0.016 | 0.052 | 0.382 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB-O | 0.231 | 0.575 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-I | −0.070 | −0.087 | 0.002 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-I | −0.134 | −0.159 | 0.010 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-I | −0.273 | −0.362 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB-I | −0.140 | −0.139 | 0.028 |

| Model | IFI | PNFI | RMSEA | CMIN/DF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated | 0.827 | 0.729 | 0.054 | 5.294 |

| Saturated | 1 | 0.000 | ||

| Independent | 0 | 0.000 | 0.123 | 23.635 |

| Interpersonal Relationship Building Methods | Distance Resulting from Management Style | Organizational Climate | Interpersonal Ties | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational climate | 0.244 | 0.705 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Interpersonal ties | 0.127 | 0.735 | 0.663 | 0.000 |

| CWB-O | 0.254 | 0.095 | −0.157 | 0.575 |

| CWB-I | −0.143 | −0.576 | −0.251 | −0.139 |

| Relationship | Parameter | Group I—Higher Education | Group II—Middle School, Vocational or Secondary Education | T Statistic | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Parameter Value | P Value | Standardized Parameter Value | P Value | ||||

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Organizational climate | 0.150 | 0.000 | 0.414 | 0.000 | −3.196 | 0.002 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Organizational climate | 0.707 | 0.000 | 0.691 | 0.000 | 0.254 | 0.800 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Interpersonal ties | 0.062 | 0.133 | 0.614 | 0.000 | −7.155 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Interpersonal ties | −0.044 | 0.110 | 0.067 | 0.163 | −0.988 | 0.326 | |

| Organizational climate → Interpersonal ties | 0.845 | 0.000 | 0.325 | 0.000 | 10.207 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-O | 0.277 | 0.000 | 0.299 | 0.000 | −0.128 | 0.898 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-O | −0.541 | 0.000 | −0.445 | 0.000 | −1.324 | 0.189 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-O | −0.131 | 0.057 | 0.395 | 0.008 | −3.774 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB-O | 0.547 | 0.000 | 0.366 | 0.017 | 3.209 | 0.002 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-I | −0.111 | 0.000 | −0.078 | 0.191 | −0.361 | 0.719 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-I | −0.263 | 0.004 | −0.064 | 0.469 | −5.033 | 0.000 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-I | −0.321 | 0.000 | −0.319 | 0.007 | −0.033 | 0.974 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB-I | −0.175 | 0.041 | −0.147 | 0.227 | −0.956 | 0.341 | |

| Assessment of level of fit | CMIN/DF = 3.668 IFI = 0.825 RMSEA = 0.057 | CMIN/DF = 3.320 IFI = 0.790 RMSEA = 0.059 | |||||

| Relationship | Parameter | Group I—35 or Younger | Group II—over 35 | T Statistic | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Parameter Value | P Value | Standardized Parameter Value | P Value | ||||

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Organizational climate | 0.198 | 0.000 | 0.263 | 0.000 | −0.782 | 0.436 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Organizational climate | 0.700 | 0.000 | 0.718 | 0.000 | −0.296 | 0.768 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Interpersonal ties | 0.207 | 0.000 | 0.297 | 0.000 | −1.195 | 0.235 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Interpersonal ties | −0.021 | 0.558 | −0.042 | 0.168 | 0.186 | 0.853 | |

| Organizational climate → Interpersonal ties | 0.691 | 0.000 | 0.652 | 0.000 | 0.743 | 0.459 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-O | 0.293 | 0.000 | 0.306 | 0.000 | −0.082 | 0.935 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-O | −0.372 | 0.003 | −0.613 | 0.000 | 3.151 | 0.002 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-O | 0.083 | 0.324 | 0.034 | 0.686 | 0.411 | 0.682 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB-O | 0.272 | 0.023 | 0.767 | 0.000 | −7.411 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-I | −0.074 | 0.081 | −0.084 | 0.024 | 0.132 | 0.895 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-I | −0.146 | 0.109 | −0.167 | 0.047 | 0.634 | 0.528 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-I | −0.271 | 0.000 | −0.424 | 0.000 | 3.601 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB-I | −0.255 | 0.005 | −0.067 | 0.449 | −8.480 | 0.000 | |

| Assessment of level of fit | CMIN/DF = 3.163 IFI = 0.794 RMSEA = 0.060 | CMIN/DF = 3.893 IFI = 0.809 RMSEA = 0.057 | |||||

| Relationship | Parameter | Group 1—Women | Group II—Men | T Statistic | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Parameter Value | P value | Standardized Parameter Value | P Value | ||||

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Organizational climate | 0.154 | 0.000 | 0.276 | 0.000 | −1.417 | 0.160 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Organizational climate | 0.691 | 0.000 | 0.738 | 0.000 | −1.446 | 0.151 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Interpersonal ties | 0.169 | 0.000 | 0.279 | 0.000 | 2.789 | 0.006 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Interpersonal ties | −0.026 | 0.269 | 0.008 | 0.810 | −0.391 | 0.697 | |

| Organizational climate → Interpersonal ties | 0.536 | 0.000 | 0.543 | 0.000 | 1.168 | 0.246 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-O | 0.097 | 0.000 | 0.109 | 0.000 | −1.227 | 0.223 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-O | −0.193 | 0.000 | −0.149 | 0.002 | 0.311 | 0.756 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-O | 0.008 | 0.742 | 0.019 | 0.559 | −0.412 | 0.681 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB-O | 0.279 | 0.000 | 0.164 | 0.004 | 1.230 | 0.222 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-I | −0.114 | 0.000 | −0.040 | 0.313 | −1.447 | 0.151 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-I | −0.178 | 0.003 | −0.037 | 0.715 | −4.276 | 0.000 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-I | −0.208 | 0.000 | −0.409 | 0.000 | 3.259 | 0.002 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB−I | −0.187 | 0.020 | −0.085 | 0.471 | −2.918 | 0.004 | |

| Assessment of level of fit | CMIN/DF = 3.899 IFI = 0.813 RMSEA = 0.059 | CMIN/DF = 2.968 IFI = 0.801 RMSEA = 0.056 | |||||

| Relationship | Parameter | Group I—Service of Fewer than 8 Years | Group II—Service of 8 Years or More | T statistic | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Parameter Value | P value | Standardized Parameter Value | P value | ||||

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Organizational climate | 0.400 | 0.000 | 0.100 | 0.003 | 3.629 | 0.000 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Organizational climate | 0.683 | 0.000 | 0.728 | 0.000 | −0.723 | 0.471 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Interpersonal ties | 0.278 | 0.000 | 0.263 | 0.000 | 0.199 | 0.843 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Interpersonal ties | 0.032 | 0.433 | −0.083 | 0.007 | 1.072 | 0.286 | |

| Organizational climate → Interpersonal ties | 0.665 | 0.000 | 0.639 | 0.000 | 0.489 | 0.626 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-O | 0.333 | 0.000 | 0.300 | 0.000 | 0.222 | 0.825 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-O | −0.615 | 0.000 | −0.412 | 0.000 | −2.914 | 0.004 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-O | 0.160 | 0.092 | −0.062 | 0.446 | 1.934 | 0.056 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB-O | 0.573 | 0.000 | 0.511 | 0.000 | 1.103 | 0.273 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-I | −0.081 | 0.108 | −0.100 | 0.005 | 0.211 | 0.833 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-I | −0.083 | 0.426 | −0.192 | 0.011 | 2.570 | 0.012 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-I | −0.321 | 0.000 | −0.365 | 0.000 | 0.734 | 0.465 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB-I | −0.193 | 0.075 | −0.158 | 0.041 | −1.018 | 0.311 | |

| Assessment of level of fit | CMIN/DF = 3.553 IFI = 0.797 RMSEA = 0.058 | CMIN/DF = 3.462 IFI = 0.813 RMSEA = 0.059 | |||||

| Relationship | Parameter | Group I—blue collar employees | Group II—Office/Clerical Staff | Group III—Management | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Parameter Value | P Value | Standardized Parameter Value | P Value | Standardized Parameter Value | P Value | ||

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Organizational climate | 0.382 | 0.000 | 0.131 | 0.000 | 0.375 | 0.000 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Organizational climate | 0.799 | 0.000 | 0.568 | 0.000 | 0.637 | 0.000 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Interpersonal ties | 0.441 | 0.000 | 0.072 | 0.016 | 0.382 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Interpersonal ties | −0.041 | 0.451 | −0.021 | 0.385 | 0.053 | 0.252 | |

| Organizational climate → Interpersonal ties | 0.450 | 0.000 | 0.648 | 0.000 | 0.379 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-O | 0.120 | 0.010 | 0.063 | 0.000 | 0.169 | 0.000 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-O | −0.192 | 0.044 | −0.180 | 0.000 | −0.116 | 0.044 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-O | 0.081 | 0.385 | 0.003 | 0.827 | 0.123 | 0.040 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB−O | 0.226 | 0.056 | 0.223 | 0.000 | 0.029 | 0.778 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-I | −0.261 | 0.000 | −0.044 | 0.108 | −0.053 | 0.365 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-I | −0.056 | 0.716 | −0.251 | 0.000 | 0.150 | 0.175 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-I | 0.016 | 0.919 | −0.293 | 0.000 | −0.121 | 0.272 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB-I | −0.328 | 0.098 | −0.106 | 0.176 | −0.450 | 0.029 | |

| Assessment of level of fit | CMIN/DF = 2.292 IFI = 0.778 RMSEA = 0.063 | CMIN/DF = 3.473 IFI = 0.817 RMSEA = 0.058 | CMIN/DF = 2.763 IFI = 0.740 RMSEA = 0.066 | ||||

| Relationship | Parameter | Group I/II | Group I/III | Group II/III | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T Statistic | P Value | T statistic | P Value | T Statistic | P Value | ||

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Organizational climate | 3.573 | 0.001 | 1.142 | 0.256 | −2.630 | 0.010 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Organizational climate | 0.362 | 0.718 | −0.288 | 0.774 | −0.536 | 0.593 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → Interpersonal ties | 4.471 | 0.000 | −1.208 | 0.230 | −4.833 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → Interpersonal ties | −0.262 | 0.794 | −1.171 | 0.244 | −0.753 | 0.453 | |

| Organizational climate → Interpersonal ties | −5.310 | 0.000 | 1.270 | 0.207 | 5.848 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-O | 0.292 | 0.771 | −1.524 | 0.131 | −1.275 | 0.205 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-O | 3.773 | 0.000 | −0.935 | 0.352 | −4.778 | 0.000 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-O | 0.937 | 0.351 | −4.128 | 0.000 | −2.591 | 0.011 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB-O | −5.510 | 0.000 | 8.429 | 0.000 | 11.705 | 0.000 | |

| Interpersonal relationship building methods → CWB-I | −2.932 | 0.004 | −3.531 | 0.001 | 0.133 | 0.894 | |

| Organizational climate → CWB-I | 6.026 | 0.000 | −6.923 | 0.000 | −11.397 | 0.000 | |

| Distance resulting from management style → CWB-I | 6.779 | 0.000 | 5.407 | 0.000 | −3.464 | 0.001 | |

| Interpersonal ties → CWB-I | −6.223 | 0.000 | 8.146 | 0.000 | 12.572 | 0.000 | |

| No. | Limitation | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Non-random selection of employee samples | This limitation is mitigated by the fact that the sample in the study was relatively large in number and demographically diverse, including in terms of education, age, sex, length of service and type of work, but also employment sector (private vs. public). |

| 2 | Partial application of face-to-face survey methods in CWB measurement | Face-to-face surveys reduce employees’ sense of anonymity. Therefore, only 10% of the total data was collected in this way, and the rest using an online survey (guaranteeing anonymity). Furthermore, about 20% of data collected by face-to-face survey had zero variance (practically the only answer was “never”). It was therefore right to use a triangulation of measurement methods, including indirect methods. The analysis excluded those questionnaires for which variance of CWB was 0. |

| 3 | The quantitative nature of scales for measuring quality of interpersonal relationships at work and counterproductive behaviors | Quantitative research has certain limitations, particularly for such complex and dynamic issues as the quality of relationships and CWB. Nevertheless, validated scales were used in the measurement, making the collected data highly reliable, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szostek, D. The Impact of the Quality of Interpersonal Relationships between Employees on Counterproductive Work Behavior: A Study of Employees in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215916

Szostek D. The Impact of the Quality of Interpersonal Relationships between Employees on Counterproductive Work Behavior: A Study of Employees in Poland. Sustainability. 2019; 11(21):5916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215916

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzostek, Dawid. 2019. "The Impact of the Quality of Interpersonal Relationships between Employees on Counterproductive Work Behavior: A Study of Employees in Poland" Sustainability 11, no. 21: 5916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215916

APA StyleSzostek, D. (2019). The Impact of the Quality of Interpersonal Relationships between Employees on Counterproductive Work Behavior: A Study of Employees in Poland. Sustainability, 11(21), 5916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215916