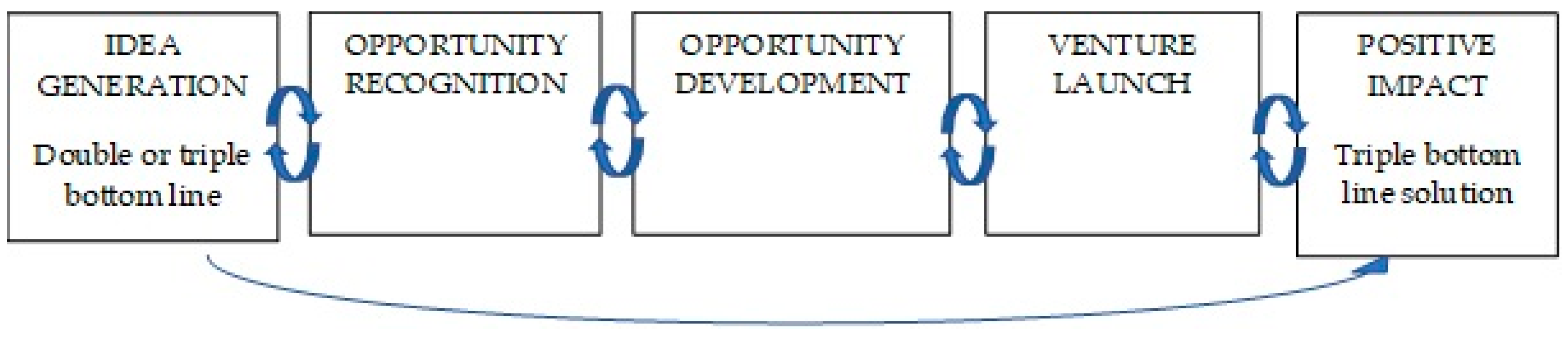

Sustainable Entrepreneurial Process: From Idea Generation to Impact Measurement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Idea Generation

2.2. Opportunity Recognition

2.3. Opportunity Development

2.4. Venture Launch and Business Exploitation

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

“However, maybe a reason why the sustainable thing came up was that these [marketing] events [in her previous work experience] produce a lot of waste of products and food. In this field, the waste is a big thing, because you have this one event, where it is like maybe 500 people, and they all get t-shirts, which they wear maybe once and throw it away. Many products used in these events go to waste just after it happens. There is no recycling or reuse. There is also the food waste. […] like one third or even sometimes, half is thrown away.”

“By 2012, every fruit my father’s farm harvested was automatically delivered to the industry. At that time, there was an excess of supply. [...] The industry did not buy our fruit and it was perfect in terms of quality. Donating food in Brazil is very difficult. So, in the farm, I started to see tons of fruit on the ground. It bothered me deeply [...] I asked my father ‘Can we think of a way to market this fruit also outside the industry?’ My dad said, “’You can try, there’s no problem.’ So, I announced a 27 kg fruit bag on a Facebook sales page. By the time I woke up, I already had 20 requests.”

“In 2014, I started a post graduate degree in business, focusing on sustainability. [...] I began to see several businesses based on conscious capitalism, i.e., you do not have to do something just to profit; you can help an entire supply chain, the ecosystem, everything around you. Then we thought about it. So, as my parents are small farmers, I already knew the dynamics of these small producers, how much they are exploited by food supply chain, so we decided to work with solutions to them, helping society with a business that is also profitable.”

“In the beginning, we were just a partner in a governmental program distributing the food parcels for poor people, but after some years we started expanding a lot, as we started to work more on the food waste issues […] by that time [in the beginning], food waste wasn’t kind of a popular theme, actually no one cared about it. Nowadays, things change and our purpose is a two-fold mission, like combat the food waste by combating the poor or combat the poor by fighting the food waste. Is there any part more important than that? Here we agreed as a team that social issues are more important. It is ok, because all those motivations are here also.”

“For example, last year we saved 1500 tons of textiles from the landfill, so we can measure our impact directly […] we also try to help homeless people. For example, we organize for them, many times a year, something like a shopping night. All the homeless people come here one evening and they can shop free. They can choose anything from our shop for free.”

“We saved more than 1,100,000 portions of food to go to waste since our begging. We have a few ways to measure it in kilograms and in CO2 saved, based on published studies in Finland. We estimate it to be approximately 430 tons of food and 2.7 million kilograms of CO2 emission reduced. Of course, the number of portions of food saved from waste is based on our operations. The kilograms and CO2 saved are based on an estimative.”

“We have rescued more than five tons of food in this year of operation. [...] The farmer was also a layman in that. At first, it was very difficult to buy from them, they just wanted to donate the food to us. They did not want to sell, but we try to work with a fairer and transparent market, so not selling would be unfair to them. We had to “educate” the farmer too, so today it’s easier. We now decide the value of the food together. We provide education campaigns also to consumers. I think both social and environmental are our social impact, at the same time, because we are reducing food waste.”

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Govindan, K. Sustainable consumption and production in the food supply chain: A conceptual framework. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 195, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fors, P.; Lennerfors, T.T. The individual-care nexus: A theory of entrepreneurial care for sustainable entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregori, P.; Wdowiak, M.A.; Schwarz, E.J.; Holzmann, P. Exploring value creation in sustainable entrepreneurship: Insights from the institutional logics perspective and the business model lens. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H. A conceptual model for social entrepreneurship directed toward social impact on society. Soc. Enterp. J. 2011, 7, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelos, C.; Mair, J.; Battilana, J.; Dacin, M.T. The embeddedness of social entrepreneurship: Understanding variation across local communities. In Communities Organ; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; pp. 333–363. [Google Scholar]

- Belz, F.M.; Binder, J.K. Sustainable entrepreneurship: A convergent process model. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Smith, B.; Mitchell, R. Toward a sustainable conceptualization of dependent variables in entrepreneurship research. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F. Entrepreneurship: Theory, Process, and Practice; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yitshaki, R.; Kropp, F. Motivations and opportunity recognition of social entrepreneurs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drencheva, A.; Folmer, E.C.; Renko, M.; Tunezerwe, S.; Williams, T.A. Social change and social ventures: Emerging developments in social entrepreneurship. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 2018, p. 1156. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, K.; Wilson, J.; Tonner, A.; Shaw, E. How can social enterprises impact health and well-being? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margiono, A.; Zolin, R.; Chang, A. A typology of social venture business model configurations. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 626–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renko, M. Early challenges of nascent social entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 1045–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mets, T.; Raudsaar, M.; Summatavet, K. Experimenting social constructivist approach in entrepreneurial process-based training: Cases in social, creative and technology entrepreneurship. In The Experimental Nature of New Venture Creation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Dimov, D. Grappling with the unbearable elusiveness of entrepreneurial opportunities. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, P. From venture idea to venture opportunity. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 943–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.F.; Husted, B.W.; Aigner, D.J. Opportunity discovery and creation in social entrepreneurship: An exploratory study in Mexico. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 81, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.; Majumdar, S. Social entrepreneurship as an essentially contested concept: Opening a new avenue for systematic future research. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E.; Carter, S. Social entrepreneurship: Theoretical antecedents and empirical analysis of entrepreneurial processes and outcomes. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2007, 14, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, A.C.O.; Guenster, N.; Vanacker, T.; Crucke, S. A longitudinal comparison of capital structure between young for-profit social and commercial enterprises. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanohov, R.; Baldacchino, L. Opportunity recognition in sustainable entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, N.M.; Parida, V.; Lahti, T.; Wincent, J. A systematic literature review of entrepreneurial opportunity recognition: Insights on influencing factors. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 12, 309–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, F.; Vurro, C.; Costanzo, L.A. A process-based view of social entrepreneurship: From opportunity identification to scaling-up social change in the case of San Patrignano. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filser, M.; Kraus, S.; Roig-Tierno, N.; Kailer, N.; Fischer, U. Entrepreneurship as catalyst for sustainable development: Opening the black box. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P. Researching Entrepreneurship; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kornish, L.J.; Ulrich, K.T. The importance of the raw idea in innovation: Testing the sow’s ear hypothesis. J. Mark. Res. 2014, 51, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorio, A.M.; Puumalainen, K.; Fellnhofer, K. Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions in sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mets, T. Creative business model innovation for globalizing SMEs. In Entrepreneurship-Creativity and Innovative Business Models; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, J.A.; Ramankutty, N.; Brauman, K.A.; Cassidy, E.S.; Gerber, J.S.; Johnston, M.; Balzer, C. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 2011, 478, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karhunen, P.; Arvola, K.; Küttim, M.; Venesaar, U.; Mets, T.; Raudsaar, M.; Uba, L. Creative Entrepreneurs’ Perceptions about Entrepreneurial Education; Paper Report; University of Tartu: Tartu, Estonia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, S. Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 448–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlmeier, R.; Rombach, M.; Bitsch, V. Making food rescue your business: Case studies in Germany. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guclu, A.; Dees, J.G.; Anderson, B.B. The process of social entrepreneurship: Creating opportunities worthy of serious pursuit. Cent. Adv. Soc. Entrep. 2002, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.; Park, J. How social entrepreneurs’ value orientation affects the performance of social enterprises in Korea: The mediating effect of social entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.; Pesci, C. Social impact measurement: Why do stakeholders matter? Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2016, 7, 99–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, S.; Ventresca, M.J. Crescive entrepreneurship in complex social problems: Institutional conditions for entrepreneurial engagement. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Social Expenditure Database (SOCX); January 2019: Social Expenditure Update; OECD: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/social/expenditure.htm (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- Reis, R. Strengths and Limitations of Case Studies; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Case | Country | Industry | Type | Observation on Site | Interview Length | Secondary Data |

| C1 | Estonia | Hotel | Not-for profit | Yes | 58 min | 8 |

| C2 | Estonia | Recycle | Not-for-profit | Yes | 35 min | 14 |

| C3 | Finland | Food sector | For-profit | Yes | 34 min | 12 |

| C4 | Finland | Food sector | For-profit | Yes | 1 h 2 min | 15 |

| C5 | Finland | Recycle | Not-for-profit | Yes | 1 h 4 min | 9 |

| C6 | Lithuania | Food sector | Not-for-profit | Yes | 1 h 31 min | 13 |

| C7 | Latvia | Food sector | Not-for-profit | Yes | 45 min | 10 |

| C8 | Denmark | Food sector | For-profit | Yes | 1 h 8 min | 21 |

| C9 | Brazil | Food sector | For-profit | Yes | 59 min | 14 |

| C10 | Brazil | Food sector | For-profit | Yes | 47 min | 6 |

| C11 | Brazil | Food sector | For-profit | Yes | 52 min | 9 |

| Propositions → Idea Generation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cases | Where Did the Idea Come from? | Prior Experience in Entrepreneurship | Prior Experiences and Skills in the Area(s) | Prior Knowledge of Product, Service or Tech | Prior Networks | |||||||||||||||||||

| C1 | One of the owners has always had an interest in themes related to nature since childhood. She and her partner decided to travel for a year to find inspiration for the business. Along the way, they visited different eco-hostels and found the idea interesting. They thought this would also help by raising awareness of the issue in the local population towards sustainable living possibilities. As the owner worked some years in marketing events, she attributes this experience also as the reason why the sustainable thing came up, since at these events people generated a lot of waste and she was always looking for solutions for this. | No | Yes, studied tourism management. Worked for four years on marketing events. | No | No | |||||||||||||||||||

| C2 | The idea came from a similar organization in another country, which inspired the whole mission of the organization, since the country was facing the same problem that could be solved in the same way. | No | Yes, one of them studied business and marketing. The other works in an environmental protection agency. | No | Yes, related to charities | |||||||||||||||||||

| C3 | The idea came from a company that already works with waste and recycling. The managers realized that the food waste is no longer a threat, but a market opportunity, since 10% to 25% of the food offered in buffet restaurants in the country is going to waste. | Yes | Yes, business management in the recycling and waste sector | No | Yes | |||||||||||||||||||

| C4 | Almost all founders knew each other beforehand. They were willing to start a business, and some of them had a special focus on sustainability issues. They saw some initiatives dealing with the core of their business elsewhere and thought they could improve it and do better. In addition, society was beginning to discuss the subject more, which would make it easier to have clients. | Yes | Yes, education in computer science, which is the core of the business | Yes, experience in information technology and digital business industry. | Yes, with angel investors, who participated in the expansion process | |||||||||||||||||||

| C5 | A similar initiative, that took place in another country facing the same situation, inspired the idea. | No | Yes, education on environmental conservation | Yes, on nature conservation association | No | |||||||||||||||||||

| C6 | During a trip abroad, the founder discovered an organization and thought he could make an equal initiative in the country. Initially, the idea was to make a unique, charitable event, to help people in the community, during the cold winter season. As the initiatives were recurring, the formal organization naturally emerged. | No | Yes, manager in a multinational company in the food sector for six years. | Knowledge related to the food sector and corporate social responsibility. | No | |||||||||||||||||||

| C7 | The organization emerged as an answer to the economic crisis faced in the country. Many people lost their jobs and did not have any money for food. As the social care system was overloaded, people started to go to charity organizations to ask for help. In this context, two big NGOs decided to come together and funded a new organization to help these people. | Yes | Yes, education in economics | No | No | |||||||||||||||||||

| C8 | The founders were having dinner in a restaurant at the time of closing and saw the employees cleaning the place and discarding food that was not consumed. They realized that it was a very large amount of food and that it was tasty. That bothered them, so they began to think in ways to solve it. | No | Yes, education in programming and business | No | No | |||||||||||||||||||

| C9 | The founder was doing a postgraduate degree in business management when he was first exposed to the idea of conscious capitalism in entrepreneurship, i.e., that he could make a business to both profit and help society. He decided to start a business to reduce food waste, mostly based on his personal history and after meeting producers who faced this problem. He began to read about other businesses. | No | Yes, studied business management with focus on sustainability (post-graduation) | No | No | |||||||||||||||||||

| C10 | The founder realized that supermarkets have some commercial practices of accepting or rejecting fresh food based on its aesthetic standard in terms of size and symmetry. This is usually called “imperfect produce”. She talked about this problem with her grandfather, who has experience in planting food. Her grandfather’s response influenced her to work on promoting solutions to this problem through entrepreneurship: “I asked the nearest person that had knowledge in these issues. ‘Okay, but what is imperfect in your garden?’ He told me: ‘Nature does not have imperfections.’ Whatever I get in my garden, I consume. Nothing is rubbish because it is bigger, smaller or looks different”. | No | Yes, education in business | No | No | |||||||||||||||||||

| C11 | Due to an oversupply, the industry rejected the product from her father’s farm. Although perfect for consumption, the fruits were thrown on the farm floor to rot. The founder saw tons of food wasted and was deeply dissatisfied with the problem. Then, she began to think of solutions to this problem. | No | Yes, her father owns a farm and she help in the marketing process | Yes, knowledge related to the food sector | No | |||||||||||||||||||

| Idea Development → Opportunity Recognition | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cases | Social Needs/Target Group | Goal | Market Orientation | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C1 | Tourists and students from local university | To provide a more sustainable living, by coming up with more affordable prices accommodations and based on environmentally friendly process | Domestic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C2 | Citizens of different social classes that seek to reuse/recycle for environmental, social or financial reasons | To make reuse and recycling as a normal everyday habit in the country, i.e., to take out of the garbage those things that are still usable and put them in circulation again | Domestic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C3 | Food sector companies that have a commercial kitchen and produce some food waste | To give concrete solutions for the food waste problem in commercial kitchens by promoting the wise use of resources | Domestic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C4 | Retail, restaurants, coffee shops or grocery stores with surplus food and consumers concerned with environmental issues and or with less economic condition | To develop and maintain digital marketplace for surplus food | International | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C5 | Citizens of different social classes that seek to reuse/recycle for environmental or financial reasons | To make reuse and recycling as a purpose of preserving the environment | Domestic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C6 | Socially disadvantaged people | To work as a mediator, collecting donated food from retailers, producers, public and providing them to the poor people. | Domestic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C7 | Socially disadvantaged people | To work as a mediator, collecting donated food from retailers, producers, public and providing them to the poor people. | Domestic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C8 | Retail, restaurants, coffee shops or grocery stores with surplus food and consumers concerned with environmental issues and/or less economic condition | To develop and maintain digital and physical marketplace for surplus food | International | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C9 | Consumers concerned with environmental and social issues | To develop and maintain digital marketplace for the delivery of baskets containing non-standard compliance and surplus food from producers | Domestic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C10 | Consumers or companies seeking convenience by receiving food at home/workplace and/or consumers concerned with environmental and social issues | To develop and maintain digital marketplace for the delivery of baskets containing general food, including non-standard compliance and surplus food from producers | Domestic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C11 | Consumers or companies seeking convenience by receiving food at home/workplace | To develop and maintain digital marketplace for the delivery of fruits, including non-standard compliance and surplus food from one producer | Domestic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Concept Development → Opportunity Development | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cases | Business Plan | Business Model | Value Proposition X Triple-Bottom Approach | Product/Service | Market and Target Group; Accessibility | Price | Promotion | Available Resources | Environmental and Social Aspects | |||||||||||||||

| C1 | No | Mix of regular business model with NGO, since it is a not-for-profit hostel; business to consumer | Sharing of intangible values, lower prices, engage multiple stakeholders, consumer education. | Hostel that promotes the concept of sustainable living, operating based on environmental solutions with a more affordable price. It also offers sustainability-related workshops | Tourists or students of the local university | More affordable price than regular hostels | Informal disclosure by friends and customers and also in the hotel booking platform | Without financial resources, they set up the place by recycling furniture taken from garbage or donations. The owner of the building gave 6 months of rent exemption. | Both dimensions were integrated, since the beginning, at the same time, however, the focus is on the environmental dimension since they began. | |||||||||||||||

| C2 | No | Mix of regular business model with NGO, since the company does not receive external resources; business to consumers | Sharing of intangible values, lower prices, consumer education | Collection of products that are no longer used, repaired if necessary, and resold | Citizens of different social classes in the country | Cheaper price for second-hand products | Posters and public campaigns, with voluntary work of marketing agencies | Only a small shop place rented with three months of rent exemption and volunteer work in the beginning | Both dimensions were integrated, since the beginning, at the same time, however, the organization exists exclusively for environmental purposes. | |||||||||||||||

| C3 | No | Regular business model, business to business | Decreasing operational costs, increasing reputation, employee’s awareness and education | Digital platform that helps kitchens to measure the food waste, understand what it is, why it has occurred, and to find possible solutions. | Restaurants, hotels, schools, other commercial kitchens | Confidential information | As the service is quite new, the company made a strong investment on a marketing campaign with possible customers | The business is part of a larger company, from which it uses the physical structure, expertise and network | Both dimensions were integrated, since the beginning, at the same time, however, the focus is only on the environmental dimension. | |||||||||||||||

| C4 | No | Classic market placement, purely commission driven; Both business to business and business to consumer | Sharing of intangible values, lower prices, convenience, engage multiple stakeholders, consumer education | A digital platform to connect sellers that have food surplus with consumers, providing food at lower costs. | Businesses such as retail, restaurants, coffee shops or grocery stores; and final consumers | Commission for every transaction, no fixed fees | Educational campaigns, social media, regular media | Knowledge, since most of the solutions provided by the company is virtual and knowledge intensive | Both dimensions were integrated, since the beginning, at the same time, however, the focus is on the environmental dimension. | |||||||||||||||

| C5 | No | Mix of regular business model with NGO, since it is not-for-profit; business to consumers | Sharing of intangible values, lower prices, consumer education | Collection of products that are no longer used, repaired if necessary, and resold. They also promote training and consulting in the environmental field | Citizens of different social classes in the country | Cheaper price for second-hand products | In the beginning, word of mouth, now, integrated social media | Partnerships and volunteer work | Both social and environmental aspects started at the same time, but the organization exists for environmental reasons | |||||||||||||||

| C6 | No | Charity NGO | Sharing of intangible values, convenience, engage multiple stakeholders, consumer education | Recovery and redistribution of food that would be wasted by actors in the food supply chain or which were harvested in campaigns to socially disadvantaged people. | People or organizations dealing with socially disadvantaged people | Free | Social networks, retail campaigns, media campaigns, donor events, and marathons in the country. | Agreements with different suppliers, venture capital, social and community volunteer work | Started only with the social dimension. Environmental aspects were integrated after. Nowadays, both dimensions are intertwined, however, the priority is the social aspect. | |||||||||||||||

| C7 | No | Charity NGO | Sharing of intangible values, convenience, engage multiple stakeholders, consumer education | Recovery and redistribution of food that would be wasted by actors in the food supply chain or which were harvested in campaigns to socially disadvantaged people. | People or organizations dealing with socially disadvantaged people | Free—now they are organizing to charge a small fee | Campaigns in the city for food donations, contact with retail and social media | Infrastructure, expertise, contacts and also, partially, the money of the “umbrella” NGO | Started only with the social dimension. Environmental aspects were integrated after. Nowadays, both dimensions are intertwined, however, the priority is the social aspect. | |||||||||||||||

| C8 | No | Classic market placement, purely commission driven; Both business to business and business to consumer | Sharing of intangible values, lower prices, convenience, engage multiple stakeholders, consumer education | A digital platform to connect sellers that have food surplus with consumers, providing food at lower costs. Also, a physical and virtual store where they sell surplus or close to expire food from producers and industry, and also food with small packaging errors | Businesses such as retail, restaurants, coffee shops or grocery stores, flower shops and final consumer | Commission for every transaction. No fixed fees | Educational campaigns, social media, regular media, educational personal projects in schools and events | Knowledge, since most of the initial solutions provided by the company is virtual and knowledge intensive. | Both dimensions were integrated, since the beginning, at the same time, however, the focus is mostly on the environmental dimension. | |||||||||||||||

| C9 | No | Regular business model, business to consumer | Sharing of intangible values, lower prices, convenience, engage multiple stakeholders, consumer education | A digital platform that sells monthly food baskets subscription to consumers for a lower price. These products would be discarded by producers for non-standard compliance or absence of a market | Final consumers of different social classes | Cheaper price, because these are products that would be discarded | Word of mouth, social media, regular media, educational personal projects in schools, companies, and food events | Without financial resources, the business started at the founders’ home, with a website developed by them and using their personal car for deliveries | Both dimensions were integrated, since the beginning, at the same time with the same focus. | |||||||||||||||

| C10 | Yes | Regular business model, business to consumer and business to business | Sharing of intangible values, lower prices, convenience, engage multiple stakeholders, consumer education | A digital platform that sells monthly food baskets subscription to consumers for a lower price. These products would be discarded by producers for non-standard compliance or absence of a market | Final consumers of different social classes and companies buying for their employees | Cheaper price, because the baskets include products that would be discarded | Social media, posters in restaurants, regular media, and food events | Without financial resources, the business started at the founders’ home | Both dimensions were integrated, since the beginning, at the same time, however, the focus is mostly on the environmental dimension. | |||||||||||||||

| C11 | No | Regular business model, business to consumer and business to business | Sharing of intangible values, lower prices, convenience, engage multiple stakeholders, consumer education | A digital platform that sells single purchases or monthly subscription to consumers for a lower price. These products would be discarded by producers for non-standard compliance or absence of a market | Final consumers of different social classes and restaurants or commercial kitchens | Cheaper price because the baskets include products that would be discarded | Word of mouth, social media, and regular media | Without financial resources, the business started by selling the product on a Facebook sales page and making deliveries with the personal car | Both dimensions were integrated, since the beginning, at the same time, however, the focus is mostly on the environmental dimension. | |||||||||||||||

| Business Development → Venture Launch | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cases | Start Year | Legal Form | Initial Team | Actual Team | Strategy | Resources: Intangible and Tangible | Financial Resources, Support | |||||||||||||||||

| C1 | 2010 | NGO | 2 owners | 2 owners and 2 employees | To reach people who are more concerned about environmental aspects and want a simpler life. Also, to integrate with them through workshops in the hostel | Creativity and time available to recycle resources rather than buying them in the market | They did not have any financial support to start the business, only received a grant to expand their activities | |||||||||||||||||

| C2 | 2004 | NGO | 2 founders and 7 volunteers | 2 founders and 100 employees | To make these second-hand centers look like normal shops (the lights, the good smell, the clothes, etc.) to attract not only poor people, but also a broader population, in order to make second-hand shopping a normal habit | Knowledge, volunteers, and donator that did not have any better options to throw away things | They did not have any financial support to start the business | |||||||||||||||||

| C3 | 2016 | Private company | 4 founders | 4 owners and 3 employees | The company usually calls potential clients, sets up a meeting and introduces the service, explaining its benefits and giving successful examples. They try to show that their service is not only about tracking the problem and reporting it, but also providing solutions with the information. | Knowledge | Funding of initiatives to support new business | |||||||||||||||||

| C4 | 2015 | Private company | 5 founders | 5 owners and 12 employees | In the business-to-business (B2B) part, the strategy was an individual approach, presenting the service offered. The initial focus was on small and medium businesses, considered easier to accept. After the initial moment, the most effective way was to show just examples. To the final consumer, it was through campaigns in social media and conventional media, with the environmental appeal and cost reduction. | Mainly intangible resources such as knowledge, dissemination of the theme in the media and society, and the ability to promote good experiences for customers | The business started with no financial resources and working in a home office. The only cost was the website’s maintenance. | |||||||||||||||||

| C5 | 1989 | Private company | 3 founders and 7 volunteers | 3 founders, 300 full-time or part-time employees and 100 volunteers | Efforts to educate the population and trying to make recycle and reusing things more common, initially word of mouth. | Knowledge and partnerships | Yes, from the government | |||||||||||||||||

| C6 | 2001 | NGO | 2 founders and 4 employers (full-time) | 2 founders, 25 full-time employees and 378 volunteers | First, search for partnerships with companies that sought to carry out corporate social responsibility actions. More recently, it has used successful cases in the same industry to recruit new donors, using an image linked to corporate responsibility and tax deductions provided by the government. | Partnerships and volunteer work | Initially, campaigns carried out in society. Nowadays, campaigns carried out in society, partnerships with the government, partnerships with the private sector, projects in partnership with municipalities and grants, and small fees from beneficiaries. | |||||||||||||||||

| C7 | 2009 | NGO | 3 founders | 3 founders, 6 full-time employees and 200 volunteers | In the beginning, collecting money donations in charity, concerts, and charity campaign donation boxes in stores. Nowadays, the money collection is a very small part of the business and they work mostly with food leftovers from the supply chain and with consumers. | Partnerships and volunteer work | Campaigns carried out in society and grants. | |||||||||||||||||

| C8 | 2016 | Private company | 2 founders | 2 owners and 208 employees | In the business-to-business (B2B) part, the strategy was an individual approach, presenting the service offered, without focusing on the company size. To the final consumer, it was through campaigns in social media and conventional media, with environmental appeal and cost reduction | Mainly intangible resources such as knowledge and dissemination of the theme in the media. | The business started with no financial resources. Then they received funding from angel investors. | |||||||||||||||||

| C9 | 2015 | Private company | 2 founders | 2 owners and 6 employees | It began with an individual approach in events and consumer fairs related to food, being disseminated after disclosure in the regular media | Partnerships and dissemination of the theme in the media, as part of a social movement | The business started with no financial resources. | |||||||||||||||||

| C10 | 2018 | Private company | 2 founders | 2 owners. Other services are outsourced | The first clients were from an incubator test base. After, the insertion in the market occurred through social media posts and media reports. | Mainly intangible resources such as knowledge and dissemination of the theme in the media. | The business started with no financial resources from the owners, but with some financial help of the incubator. | |||||||||||||||||

| C11 | 2012 | Private company | 1 founder | 2 owners and 10 employees | The first customer was through a Facebook sales page | Mainly intangible resources such as knowledge and dissemination of the theme in the media. | The business started with no financial resources. | |||||||||||||||||

| Business Exploitation → Impact Measurement | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cases | Social and Environmental Impact | Problems Facing | Future Plans | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C1 | Pioneers in the city in the process of separation and final destination of different types of waste. They pressed the city government to introduce more sustainable systems to deal with waste. All furniture is recycled, and the sheets, towels, and blankets are second-hand, bought from luxury hotels that periodically exchange their items. Offers a more affordable and fairer price. Promotes educational workshops and recycling activities in the community with guests on various topics related to sustainability. | They would like to be more active in terms of promoting sustainability, but the business routine requires too much dedication in communicating with guests. | To find mechanisms that enable the operation with solar energy, to increase the reach of the workshops, and to find strategies to attract more concerned with sustainability clients | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C2 | In environmental terms, recycling and reusing, since the past year the company saved 1500 tons of textiles from the landfill. In the social aspect, a cheaper price and social charity. For example, they organize a “shopping night”, many times a year, for homeless people, when they can choose anything from the shop for free. | The destination of clothing leftovers that people did not want, since nowadays, it is donated to a long-distance organization and they understand that it is not a very sustainable solution. | To cover all the country (currently they have 11 stores) in order to provide, in every place, conditions for people to have the opportunity of giving things away. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C3 | Environmentally, a total of 217,920 kg of food was saved from being wasted in 2017, translating into over 400,000 lunch meals. It represents almost 500,000 euros in cost savings. Socially, they promote a more critical perception in society about waste. Some restaurants, after beginning measurements, realized that the value of wasted useful food is more than twice as great as estimated. In addition, they participate in the discussion about food waste with other stakeholders. | To raise awareness of some restaurants about the problem, because they often do not realize the relevance of the issue | To expand operations in the country and in other Nordic countries through international chains. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C4 | They save more than 67,000 portions of food from being thrown away every month, which corresponds to saving 167 tons of CO2 emissions every month. Consumers are able to obtain food with a 50% discount, which makes it affordable for people that have a low income. They also carry out educational campaigns and workshops, promoting more awareness of the food waste problem. | The costs of starting operations in new countries | To find a way to scale the business | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C5 | Environmentally, promotion of reusing and recycling. Socially, in addition to education, as a social enterprise, more than 70% of the team who train and qualify for the professional market consists of people in situations of social vulnerability, such as unemployed, alcoholics in treatment, and people with minor convictions. | Training and qualification of people, in vulnerability situations, are often not fit or the training time is not sufficient | To expand operations in the country and other countries | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C6 | Promotes efficient use of resources and public solidarity in reducing responsible consumption of food. In 2017, a total of 7456 tons of food were recovered and donated. The company was responsible for initiating a roundtable discussion with different institutions to discuss solutions to food waste. | To manage volunteer work, especially in recruitment and long-term retention issues | To expand operations and the network capacity | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C7 | In 2017, they donated 40 tons of food, providing assistance to 23,000 people in total, generally families with an average income of 350 euros. | The regional partners do not have transport or enough money for all operations. In addition, there is no national regulation about how to deal with the waste. It affects the donation of food best-before and use by date, even if it is suitable for consumption. There is a lack of knowledge about this issue and society does not understand the difference, among other things. | To organize conferences to put together all donators and partners, from the ministry and the government, to discuss new solutions to food waste issues | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C8 | They calculated that they saved 13 million meals from being wasted, which corresponded to approximately a 27 million CO2 reduction. Consumers are able pay lower prices for food, which makes it affordable for people that have a low income. They also carry out educational campaigns and workshops, promoting more awareness of the food waste problem. | Find the best cultural approach to campaigns with consumers in each country | To expand operations in other countries | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C9 | In addition to the environmental aspect, based on sales data, the company saved 600 tons of fruits and vegetables from wasting since the beginning of the operation. They help producers have better living conditions in Brazil and promote several awareness campaigns about food waste issues, which are disseminated to their 1500 weekly customers, and to the public through the news. | Manage the logistics of buying from small producers who have small amounts of food and live in areas that are more isolated. | To better organize the management and logistics structure in order to expand activities | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C10 | The company helped prevent more than 5 tons of food waste by educating producers that there are alternative markets for these products and promoting consumer awareness. | Some vegetables are rejected by consumers and they need to make more of an effort to share recipes to prepare food and remind consumers that the business proposal is to accept these rejected food. | To expand operations in the city | |||||||||||||||||||||

| C11 | The company avoids 170 tons of fruit from being wasted per month, in addition to decreasing the grower’s dependence on the industry, | To deal with the fruit off season | To increase the number of sales | |||||||||||||||||||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matzembacher, D.E.; Raudsaar, M.; de Barcellos, M.D.; Mets, T. Sustainable Entrepreneurial Process: From Idea Generation to Impact Measurement. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5892. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215892

Matzembacher DE, Raudsaar M, de Barcellos MD, Mets T. Sustainable Entrepreneurial Process: From Idea Generation to Impact Measurement. Sustainability. 2019; 11(21):5892. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215892

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatzembacher, Daniele Eckert, Mervi Raudsaar, Marcia Dutra de Barcellos, and Tõnis Mets. 2019. "Sustainable Entrepreneurial Process: From Idea Generation to Impact Measurement" Sustainability 11, no. 21: 5892. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215892

APA StyleMatzembacher, D. E., Raudsaar, M., de Barcellos, M. D., & Mets, T. (2019). Sustainable Entrepreneurial Process: From Idea Generation to Impact Measurement. Sustainability, 11(21), 5892. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215892