Rethinking Institutional Knowledge for Community Participation in Co-Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Developments towards Participation in Cameroon

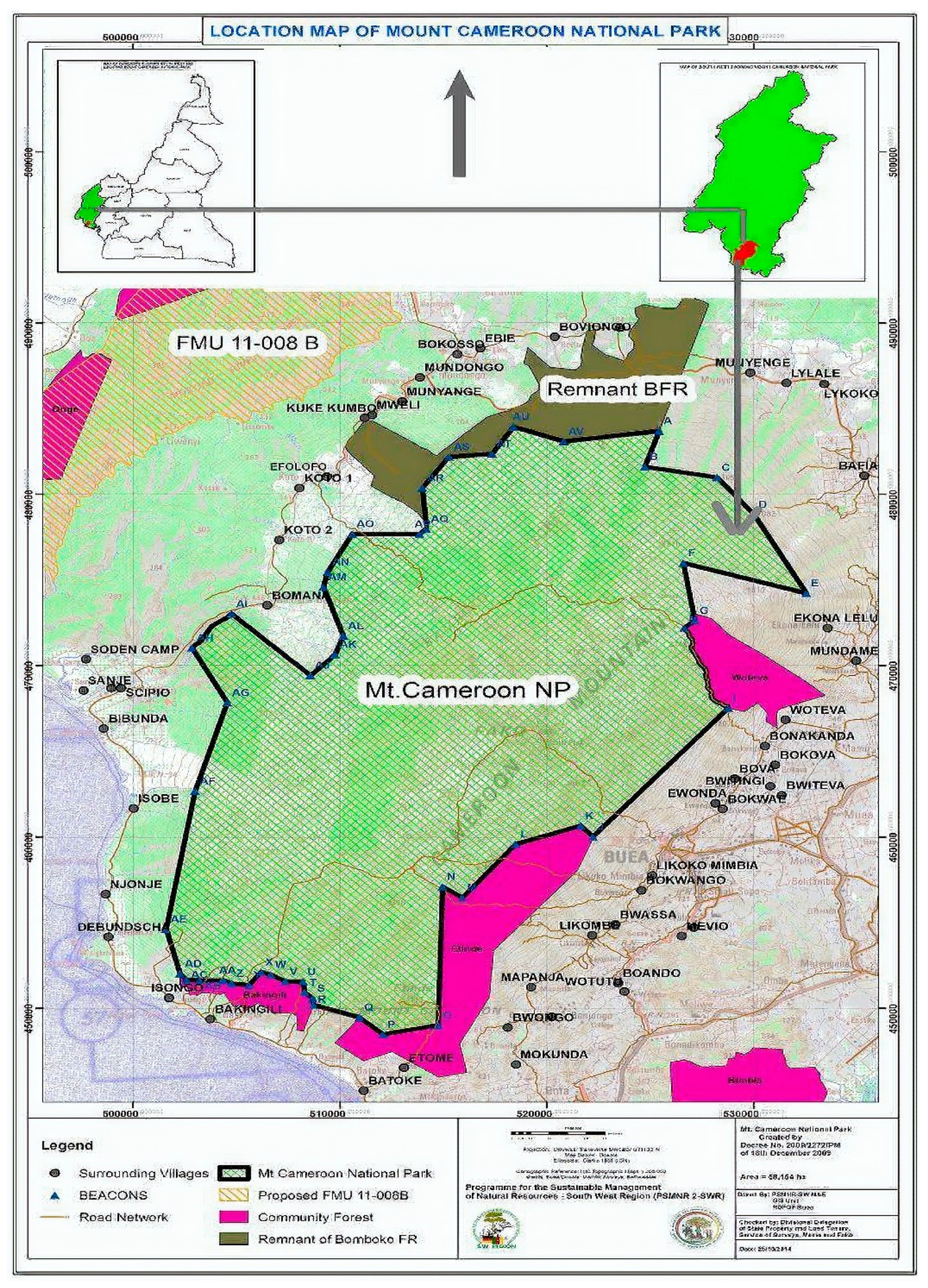

2.1. Study Area and Political Organization

- Subdivisional councils led by mayors corresponding to all five subareas.

- Within the subdivisions are villages led by chiefs who are responsible for dispute settlement, organizing traditional ceremonies, and codifying customary law.

- The MCNP Service leads the development and co-management of MCNP, including adjacent villages, in collaboration with partner organizations.

2.2. Legalities for Institutional Participation in Communities

- Laws for the participation of local communities and co-management institutions (subdivisional councils, NGOs, and state organs).

- The 2014 co-management plan for MCNP and the participation of locals and partner agencies.

2.3. Co-Management Framework

3. Materials and Methods

- Subdivisional councils, NGOs, and state organs actively involved in facilitating co-management and whose head offices are permanently stationed in the southwest region of Cameroon.

- Selecting officials in each institution, whose duties pertain to co-management at community levels of society.

- Experts who provided their informed consent and acceptance for interviews following phone calls and visits to offices.

4. Results

4.1. Local Concerns about Participation

“The park people are slow in acting. I have not seen anything that I would class as development in our community as far as the park is concerned. Not all activities promised by the park authorities have been fulfilled. We get very little help and what we do get cannot fully support village projects. A good number of locals still do not understand the conservation development agreement between the park and the community.”(Field data, 2017)

“I am not happy because the main problem for us, locals, is the lack of drinkable water and sufficient water for our farms. At the beginning of the co-management, the authorities ran the projects well, but they have not seen things through properly. They keep on postponing their plans to act. This is why I am not pleased with the participation system. More is still expected from the park officials.”(Field data, 2017)

“The remoteness of the village makes it hard for farmers to transport cocoa to the market. At times, the farmers have to wait and hope for traders to arrive from far away, which is usually difficult. I am hoping that the government could support the community by maintaining the road conditions. Some of the budget for roads could be used to employ youths who do not have jobs, so as they could assist in renovating the roads for farmers and traders.”(Field data, 2017)

“I am aware that the locals need to help protect wildlife in the park, but it is also important for park officials to respect our farmland that is located close to the park boundary. Despite the support we gave to officials in the past, they take our farms without any dialogue.”(Field data, 2017)

“The population has increased over the years. People cut down trees and do not know which trees the forestry law protects. Some of the locals have trees on their farmland but are told not to cut them down without consulting with park management authorities. The laws are outdated and need to be revised to help the locals know what to do in promoting biodiversity conservation.”(Field data, 2017)

4.2. Institutional Knowledge, Expertise, and Capacity for Action

“In the past, most activities done in cooperation with local communities were centralized. It is only in recent years that we are beginning to have the decentralization laws implemented. Our institutional role of working with locals is still very new. One of our goals is to explore ways of transforming natural resources into avenues of development to serve the communities. The laws are, however, clear and our council tries to comply with them. The council aims at having a common understanding with the locals, making them know the limits of using the forest traditionally. Be it harvesting timber and hunting animals for their cultural needs, we need to ensure that the locals can sustain biodiversity. The council’s tasks are at times limited by a lack of finances. There are many financial constraints against achieving some of its goals. The council intends to collaborate more with various conservation agencies and local communities to develop MCNP resources in ways that can improve the Bomboko road and the wellbeing of people living around MCNP.”(Field data, 2017)

“The villages in the Idenau area have a memorandum of understanding with the MCNP Service and its partners. Since the creation of the park, the locals signed several documents and deposited them at the council. The council, therefore, engages in every activity to do with the locals and the park authorities. One area of interest for us is collaborating with forest management committees, through which we help the locals to understand what animals and trees can be preserved. I must admit that the coming of the park has altered the traditions of the people. There are heritage sites in the park that the locals once freely visited to perform their rituals. Nowadays, the locals have to obtain permission from the park authorities before entry. The council also aims at encouraging the locals on how they can make use of nontimber forest products to generate income. As the park is here to stay, there is an obligation to train the locals in skills they can adopt to be self-reliant, such as the management of beehives and providing social amenities for the communities.”(Field data, 2017)

“The communities around Mount Cameroon now have a protected area. There is a need for regulated approaches to forest exploitation. The lawmakers must take into account the plight of local people so they do not feel left out. MINEPAT comes in at this level to coordinate stakeholders in the southwest region. The aim is to develop a common mapping platform tool in the next five years, to facilitate access to information between villages and agencies in the field. This will make it easier for various actors to understand development needs and act from a common standpoint where everyone is included in decision-making. Both the village chiefs and council mayors have an important role to play in this process.”(Field data, 2017)

“PNDP operates in several sectors involving agriculture, water, mining, administration, and security. One of our aims is helping regional councils realize their community development plans. Through the councils, PNDP can identify what needs the villages have and what represents a priority project for financing. Upon approval of such plans, PNDP directly participates in villages by conducting feasibility studies, designing microprojects, and disbursing funds to help councils realize these projects.”(Field data, 2017)

“As far as co-management is concerned, the local people are part and parcel of the decision-making process. In the past, we have had foreign agencies visiting with pre-conceived ideas, which the locals often find hard to understand. Our focus has been to understand local perceptions about the use of natural resources and what interests they have in the park. A difficulty is that many of the locals still believe biodiversity will be available forever without depletion. Our organization helps to ensure that the locals can continue to rely on certain plants in the forest for traditional healing. We are exploring ways to promote local participation in the sustainable use of forest through the option of access cards that will enable local people to use the park in a controlled manner.”(Field data, 2017)

“One difficulty with preserving the biodiversity of MCNP comes from poaching activities. It is, therefore, an important goal of our capacity-building unit to train and educate locals on wildlife conservation, to reduce the frequent occurrence of illegal activities in protected areas. There is the saying that ‘you can sell an elephant a thousand times when you use a camera and not a bullet.’ One of our future priorities is to develop new educational courses on biodiversity conservation, targeting the basic educational sector in the southwest region.”(Field data, 2017)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Edwards, A.D.; Dorothy, D.J. Community and Community Development; De Gruyter Mouton: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mees, L.P.; Heleen, C.J.U.; Dries, L.T.H.; Peter, P.J.D. From Citizen Participation to Government Participation: An exploration of the roles of local Governments in Community initiatives for Climate Change Adaptation in the Netherlands. Environ. Policy Gov. 2019, 29, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, S.; Mohan, G. (Eds.) Participation-From Tyranny to Transformation?: Exploring New Approaches to Participation in Development; Zed Books: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, F. Participatory Governance: From Theory to Practice; Oxford Handbook of Governance: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor, N. Between Citizenship and Clientship: The Politics of Participatory Governance in Malawi. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2010, 36, 801–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, S.; Buchecker, M. Does Participatory Planning foster the Transformation toward more Adaptive Social-ecological Systems? Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán, A.M.; Duit, A.; Schultz, L. Does Stakeholder Participation increase the Legitimacy of Nature Reserves in Local Communities? Evidence from 92 Biosphere Reserves in 36 countries. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2019, 21, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, D. The Origins and Evolution of the Conservation-poverty Debate: A Review of Key literature, Events and Policy processes. Oryx 2008, 42, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchoungui, B.; Gartlan, S.; Simo, J.A.M.; Youmbi, A.; Ndatsana, M.; Winpenny, J. Structural Adjustment and Sustainable Development in Cameroon; A World Wide Fund for Nature Study, Working Paper 83; Chameleon Press: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ngwoh, V.K. Cameroon: State Policy as Grounds for Indigenous Rebellion. The Bakweri Land Problem, 1946–2014. Confl. Stud. Q. 2019, 27, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, J.; MacKinnon, K.; Child, G.; Thorsell, J. Managing Protected Areas in the Tropics; IUCN: Grang, Switzerland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ballet, J.; Koffi, K.J.M.; Komena, B.K. Co-management of Natural Resources in Developing Countries: The Importance of Context. Econ. Int. 2010, 120, 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Brockington, D.; Duffy, R. Capitalism and Conservation: The Production and Reproduction of Biodiversity Conservation. Antipode 2010, 42, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, K.B.; Pimbert, M.P. Social Change and Conservation: Environmental Politics and Impacts of National Parks and Protected Areas; Earthscan: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholdson, O.; Porro, R. Brokers—A Weapon of the Weak: The Impact of Bureaucrazy and Brokers on a Community-Based Forest Management Project in the Brazilian Amazon; Forum for Development Studies; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, B.; Kothari, U. (Eds.) Participation: The New Tyranny? Zed Books: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brockington, D. Corruption, Taxation and Natural Resource Management in Tanzania. J. Dev. Stud. 2008, 44, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantongo, M.; Vatn, A.; Vedeld, P. All that Glitters is not Gold; Power and Participation in Processes and Structures of Implementing REDD+ in Kondoa, Tanzania. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 100, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. Evaluating Participatory Development: Tyranny, Power and (Re) politicization. Third World Q. 2004, 25, 557–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, M.; Tiffany, H.M.; McAlpine, C. Power, Politics and Policy in the Appropriation of Urban wetlands: The Critical Case of Sri Lanka. J. Peasant Stud. 2019, 46, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, E.A. Participation and accountability in development management. J. Dev. Stud. 2003, 40, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockington, D.; Larsen, P.B. (Eds.) The Anthropology of Conservation NGOs. Rethinking the Boundaries. Palgrave Studies in Anthropology of Sustainability; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brockington, D.; Scholfield, K. The Work of Conservation Organisations in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2010, 48, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosli, M.; Dörfler, T. Why is Change so Slow? Assessing Prospects for United Nations Security Council Reform. J. Econ. Policy Reform 2019, 22, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antweiler, C. Local Knowledge Theory and Methods: An Urban Model from Indonesia. In Investigating Local Knowledge. New Directions, New Approaches; Bicker, A., Sillitoe, P., Pottier, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lemoigne, N. From One Risk to Another: International Projects and Food Risk in Cameroon. A Corrupted Approach? In Risk and Africa. Multi-Disciplinary Empirical Approaches; Bloemertz, L., Doevenspeck, M., Macamo, E., Muller-Mahn, D., Eds.; Deutsche Nationalbibliothek: Leipzig, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reinsberg, B.; Kentikelenis, A.; Stubbs, T.; King, L. How Structural Adjustment Programs Impact Bureaucratic Quality in Developing Countries; Working paper Series 452; Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts Amherst: Amherst, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Cameroon. Law No 94/01 of 20th January 1994 to Lay down Forestry, Wildlife, and Fisheries Regulations. Republic of Cameroon, 1994. Available online: http://www.forestlegality.org/risk-tool/country/cameroon-0 (accessed on 4 July 2019).

- Fon, F. An Analysis of Co-Management on the Development and Preservation of Natural Resources on the Mount Cameroon National Park; Wildlife College: Garoua, Cameroon, 2013; Available online: http://www.ecoledefaune.org/internal_images/rapport-b2-forlemu-fon.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2019).

- Nachmany, M.; Fankhauser, S.; Davidová, J.; Kingsmill, N.; Landesman, T.; Roppongi, H.; Schleifer, P.; Setzer, J.; Sharman, A.; Singleton, S.C.; et al. Climate Change Legislation in Cameroon. An Excerpt from the 2015 Global Climate Legislation Study. A Review of Climate Change Legislation in 99 Countries. 2015. Available online: http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/CAMEROON.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- Republic of Cameroon. Law on Decentralization. Republic of Cameroon. Municipal Development Counseling. MUDEC Group, 2004. Available online: http://mudecgroup.org/?p=784 (accessed on 13 June 2019).

- Numvi, G. Decentralization and Community Participation: Local Development and Municipal Politics in Cameroon; Langaa Research and Publishing Common Initiative Group: Bamenda, Cameroon, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Charlotte, C.N. Management Plan of the Mount Cameroon National Park and Its Peripheral Zone. Cameroon. 2014. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/290571468007177234/Management-plan-of-the-Mount-Cameroon-national-park-and-its-peripheral-zone (accessed on 3 September 2019).

- Cunningham, A.; Anoncho, V.F.; Sunderland, T. Power, Policy and the Prunus Africana Bark Trade, 1972–2015. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 178, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngang, E.N.M. Simple Manual on the Legal Framework, Creation, and Management Principles of Civil Society Organizations in Cameroon. PASOC, EU Support Program for the Structuring of Civil Society, Cameroon. 2015, pp. 1–25. Available online: http://www.academia.edu/11825767/Simple_Manual_on_The_Legal_Framework_Creation_and_Management_Principles_of_Civil_Society_Organisations_in_Cameroon (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2019, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, B.; Aida, H.; Ain, F.; Woollard, J. Collecting data via Instant Messaging Interview and Face-to-face Interview: The Two Authors Reflections. In Proceedings of the INTED 2019: The 13th Annual International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, 11–13 March 2019; University of Southampton Institutional Repository: Southampton, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Loeb, S.; Dynarski, S.; McFarland, D.; Morris, P.; Reardon, S.; Reber, S. Descriptive Analysis in Education: A Guide for Researchers; NCEE 2017-4023; ERIC Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 1–53. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED573325 (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Wibeck, V.; Linnér, B.; Alves, M.; Asplund, T.; Bohman, A.; Boyko, M.T.; Feetham, P.M.; Huang, Y.; Nascimento, J.; Rich, J.; et al. Stories of Transformation: A Cross-Country Focus Group Study on Sustainable Development and Societal Change. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Satsangi, K.; Satsangee, N. Identification of Entrepreneurial Education Contents using Nominal Group Technique. Educ. Train. 2019, 61, 1001–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MCNP Cluster Zone | Village Community | Population | Economic Activities | Dependence on Forest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buea | Bonakanda | 1000–1500 | Farming of cocoyams, plantains, potatoes, and cassava | Timber harvesting, Bee keeping, and animal trapping |

| West Coast | Lower Boando | 500 | Fishing and the sale of fish Palm nut farming, harvesting, and sales Extraction and sale of oil palm | Timber and bamboo harvesting Bee keeping |

| Batoke | >2000 | |||

| Bakingili | >2000 | |||

| Njonje | <1000 | |||

| Bibunde | >2000 | |||

| Sanje | 500–1000 | |||

| Muyuka | Lykoko | >2000 | Fuel wood sales; rearing goats, fowls, and pigs The sale of honey | Timber and bamboo harvesting, bee keeping |

| Munyenge | >2000 | |||

| Bomboko | Bomana | 1000–1500 | Cocoa cultivation and sales; farming corn, cocoyam, plantains, and cassava Rearing cows and goats | Animal trapping, timber harvesting Harvesting of medicinal plants The use of caves for spiritual needs |

| Big Koto I | 1000–1500 | |||

| Efolofo | 500–1000 | |||

| Kuke Kumbo | 1000–1500 | |||

| Munyange | 500–1000 | |||

| Mundongo | 500–1000 | |||

| Bova Bomboko | >2000 | |||

| Boviongo | 500 |

| Subdivisional Councils | State Organs | NGOs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional Division | Expert | Organ | Expert | Organization | Expert |

| Buea | Deputy staff | Programme Nationale pour le Developpement Participatif (PNDP) | Senior Staff | Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) project unit | Project leader |

| Limbe II | Senior staff | Ministère des Forêts et de la Faune (MINFOF) regional delegation | Senior Staff | Environment and Rural Development Foundation (ERUDEF) | Development Expert |

| Mbonge | Deputy staff | Ministère de l’Economie, de la Planification et de l’Aménagement du Territoire (MINEPAT) | Service staff | WWF local unit | Educator |

| Muyuka | Deputy staff | South West Development Authority (SOWEDA) | Technical staff | Mount Cameroon Ecotourism Organization (Mt. CEO) | Senior staff |

| Idenau | Deputy staff | Limbe Wildlife Centre (LWC) | Senior staff | ||

| Limbe Botanical and Zoological Garden | Absent | ||||

| MCNP Service | Staff assistant | ||||

| MCNP Cluster Zone | Study Village | Focus Group No. | No. of Participants | Age Group | Male: Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buea | Bonakanda | 1 | 16 | 16–60+ | 13:3 |

| West Coast | Lower Boando | 2 | 16 | 16–60+ | 12:4 |

| Batoke | 3 | 16 | 26–60+ | 9:7 | |

| Bakingili | 4 | 16 | 26–60+ | 11:5 | |

| Njonje | 5 | 16 | 26–60 | 9:7 | |

| Bibunde | 6 | 14 | 26–60 | 12:2 | |

| Sanje | 7 | 16 | 16–60+ | 15:1 | |

| Muyuka | Lykoko | 8 | 16 | 26–60+ | 12:4 |

| Munyenge | 9 | 16 | 16–60+ | 12:4 | |

| Bomboko | Bomana | 10 | 16 | 26–60+ | 14:2 |

| Big Koto I | 11 | 16 | 26–60 | 13:3 | |

| Efolofo | 12 | 16 | 26–60 | 14:2 | |

| Kuke Kumbo | 13 | 16 | 26–60 | 15:1 | |

| Munyange | 14 | 16 | 26–60+ | 16:0 | |

| Mundongo | 15 | 16 | 16–60+ | 15:1 | |

| Bova Bomboko | 16 | 16 | 16–56 | 14:2 | |

| Boviongo | 17 | 16 | 26–60+ | 13:3 |

| Study Village | Focus Group No. | No. of Participants | Community Needs | No. of Counts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonakanda | 1 | 16 | Youth employment and community halls | 13 |

| Lower Boando | 2 | 16 | Farm equipment and workshop | 10 |

| Batoke | 3 | 16 | Youth employment | 12 |

| Bakingili | 4 | 16 | Water supply | 8 |

| Njonje | 5 | 16 | Funding to fishermen and respecting farm boundary | 9 |

| Bibunde | 6 | 14 | Modifying farm-to-park boundary | 8 |

| Sanje | 7 | 16 | Finding assistance to fishermen | 10 |

| Lykoko | 8 | 16 | Distancing park boundary from farmland | 11 |

| Munyenge | 9 | 16 | Water supply | 8 |

| Bomana | 10 | 16 | Sensitization on conservation, supply farm equipment, and training new techniques for crop cultivation | 10 |

| Big Koto I | 11 | 16 | Supply water, electricity, and telecommunication networks | 9 |

| Efolofo | 12 | 16 | Electricity and water supply | 7 |

| Kuke Kumbo | 13 | 16 | Health center, water supply, and farm tools | 11 |

| Munyange | 14 | 16 | Youth employment and health care | 16 |

| Mundongo | 15 | 16 | Water supply and telecommunication networks | 13 |

| Bova Bomboko | 16 | 16 | Health center, water supply, and improve farm‒market roads | 11 |

| Boviongo | 17 | 16 | Water supply | 14 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akonwi Nebasifu, A.; Majory Atong, N. Rethinking Institutional Knowledge for Community Participation in Co-Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205788

Akonwi Nebasifu A, Majory Atong N. Rethinking Institutional Knowledge for Community Participation in Co-Management. Sustainability. 2019; 11(20):5788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205788

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkonwi Nebasifu, Ayonghe, and Ngoindong Majory Atong. 2019. "Rethinking Institutional Knowledge for Community Participation in Co-Management" Sustainability 11, no. 20: 5788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205788

APA StyleAkonwi Nebasifu, A., & Majory Atong, N. (2019). Rethinking Institutional Knowledge for Community Participation in Co-Management. Sustainability, 11(20), 5788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205788