Culture and Tourism in Porto City Centre: Conflicts and (Im)Possible Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Culture and Tourism: Dependencies and Conflicts

- Intergenerational equity: do not compromise the capacities of future generations to access cultural resources and meet their cultural needs;

- Intragenerational equity: provide equity in the access to cultural production, participation and enjoyment to all members of the community on a fair and non-discriminatory basis;

- Importance of diversity: the value of cultural diversity in the processes of economic, social and cultural development should be considered;

- Precautionary principle: a risk-averse position should be adopted to avoid decisions with irreversible consequences for cultural capital, such as the destruction of cultural heritage or the extinction of valued cultural practices; and

- Interconnectedness: a holistic approach that recognizes the interconnectedness between social, environmental, economic and cultural development should be adopted.

3. Materials and Methods

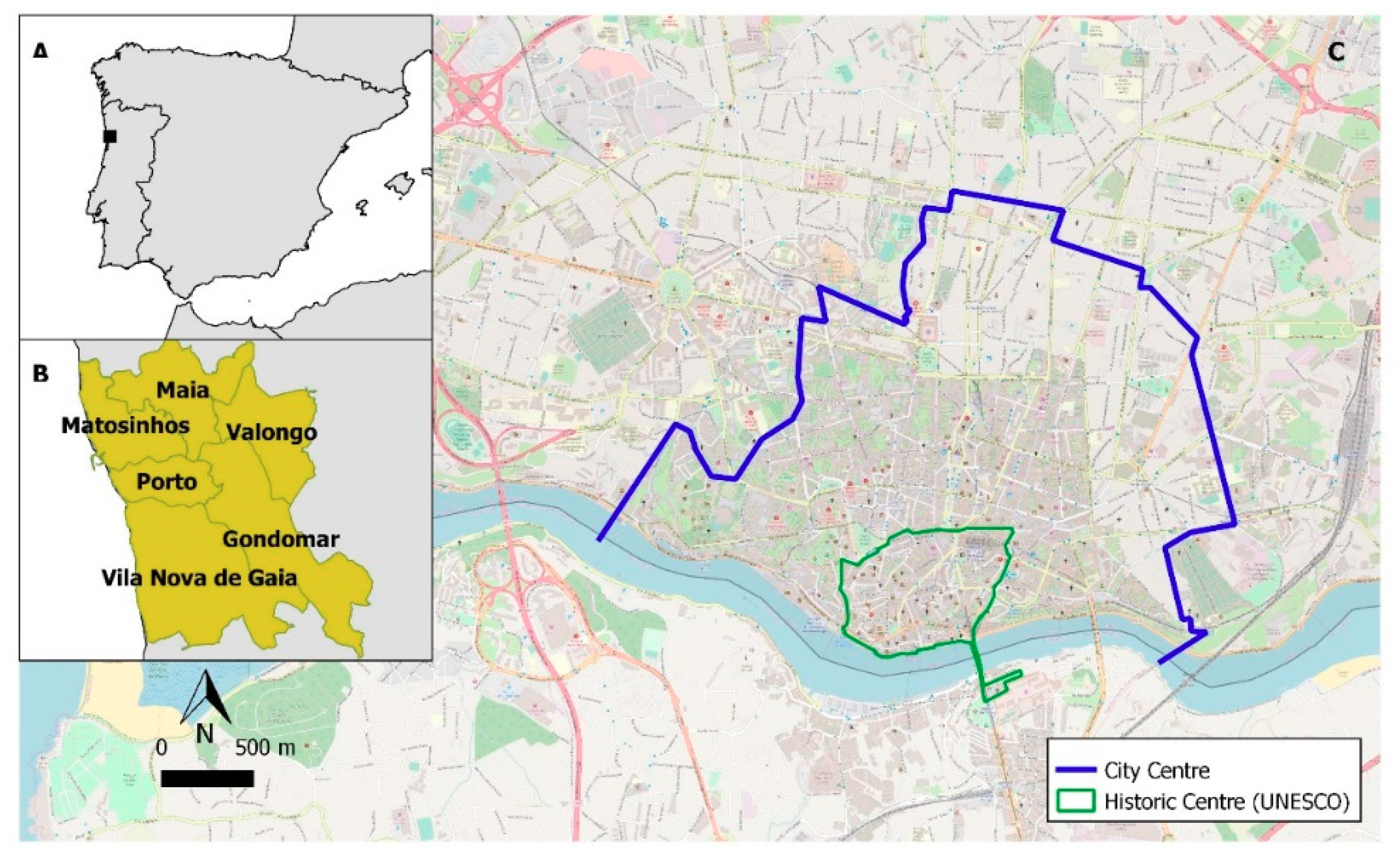

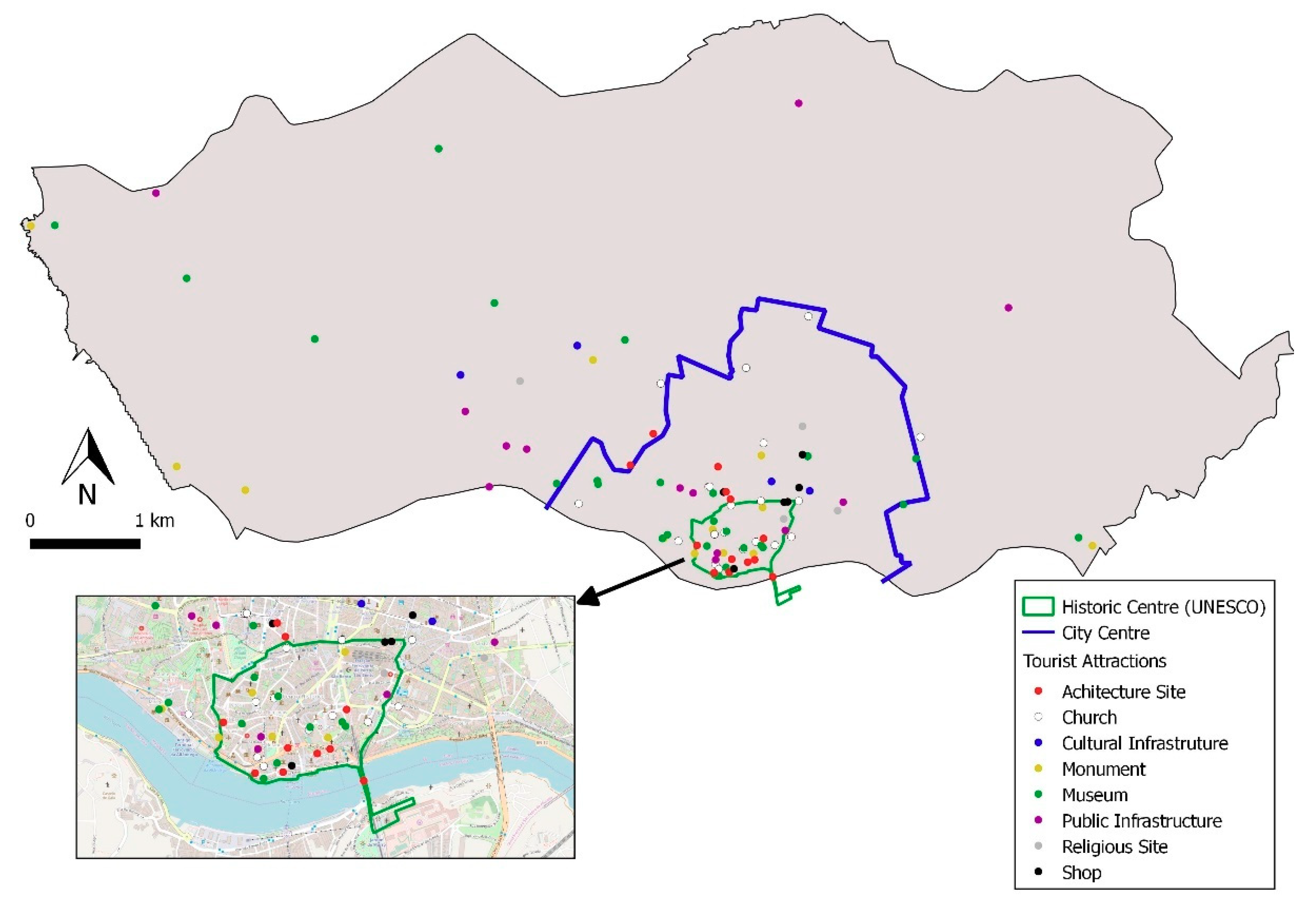

3.1. Case Study

3.2. Research Methodology

4. Results

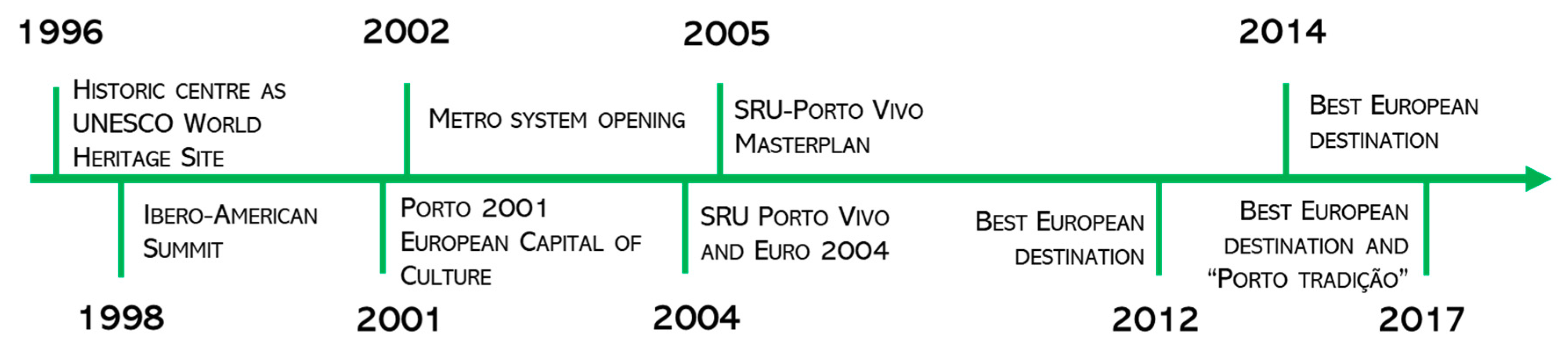

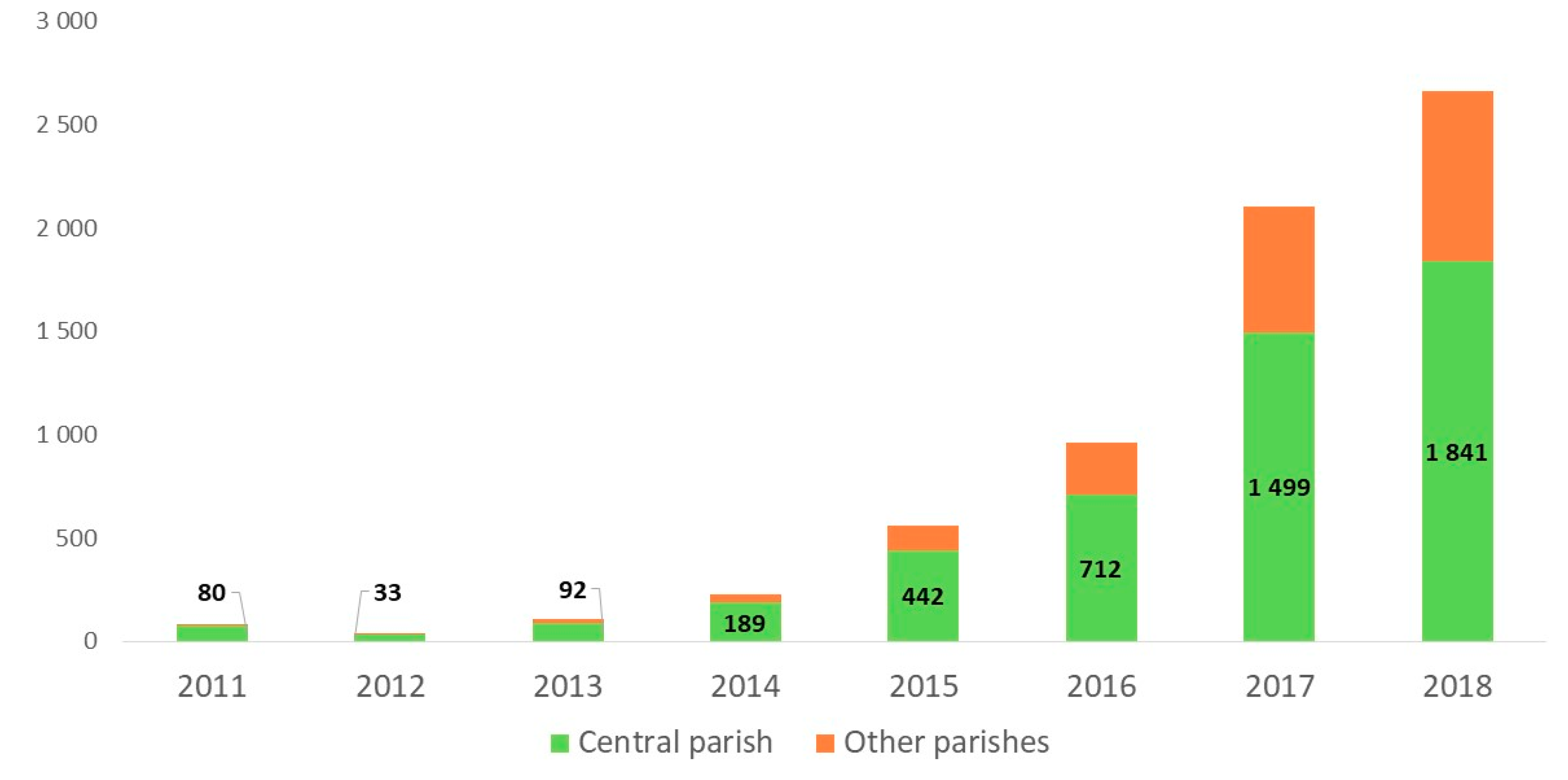

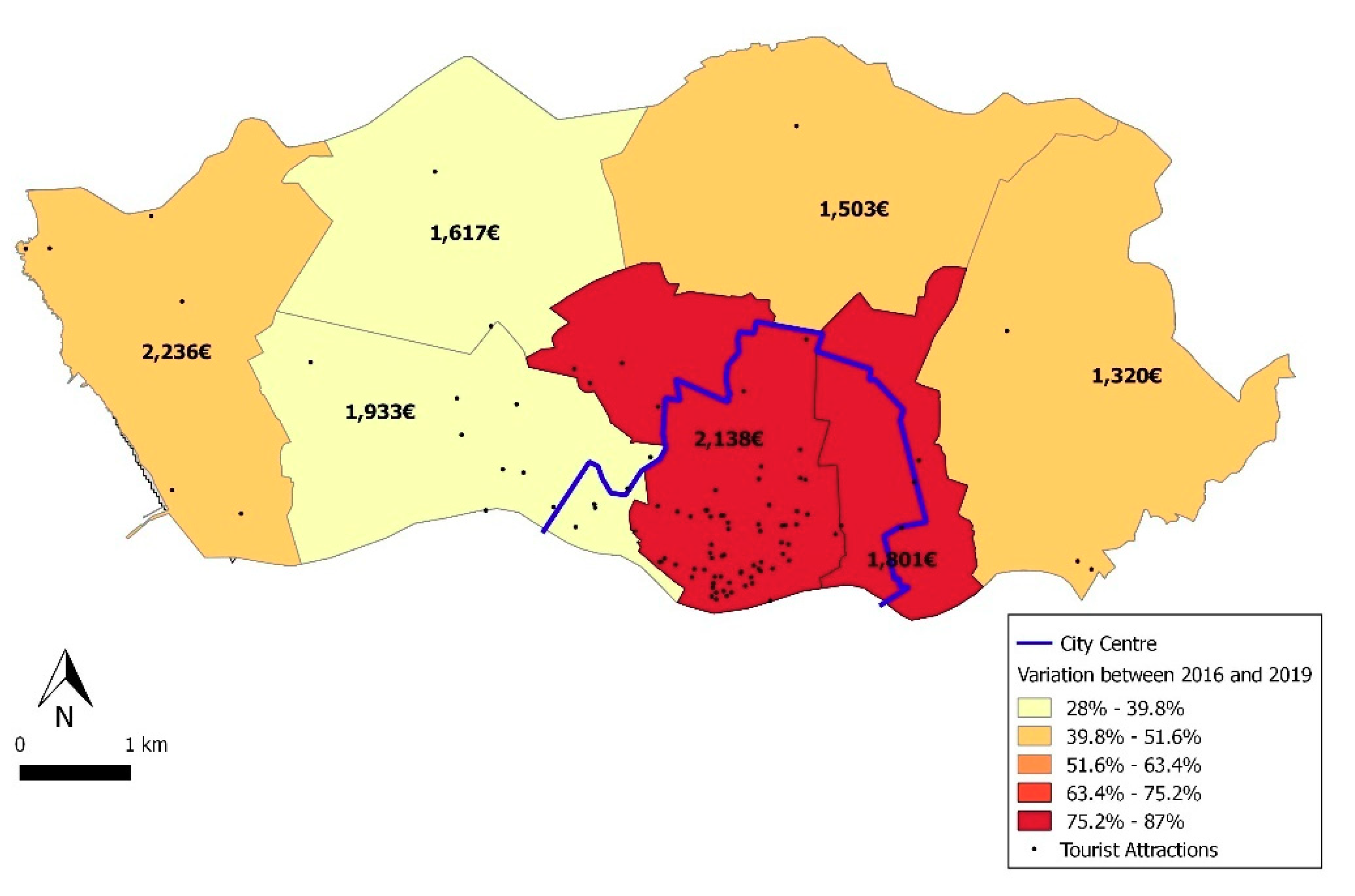

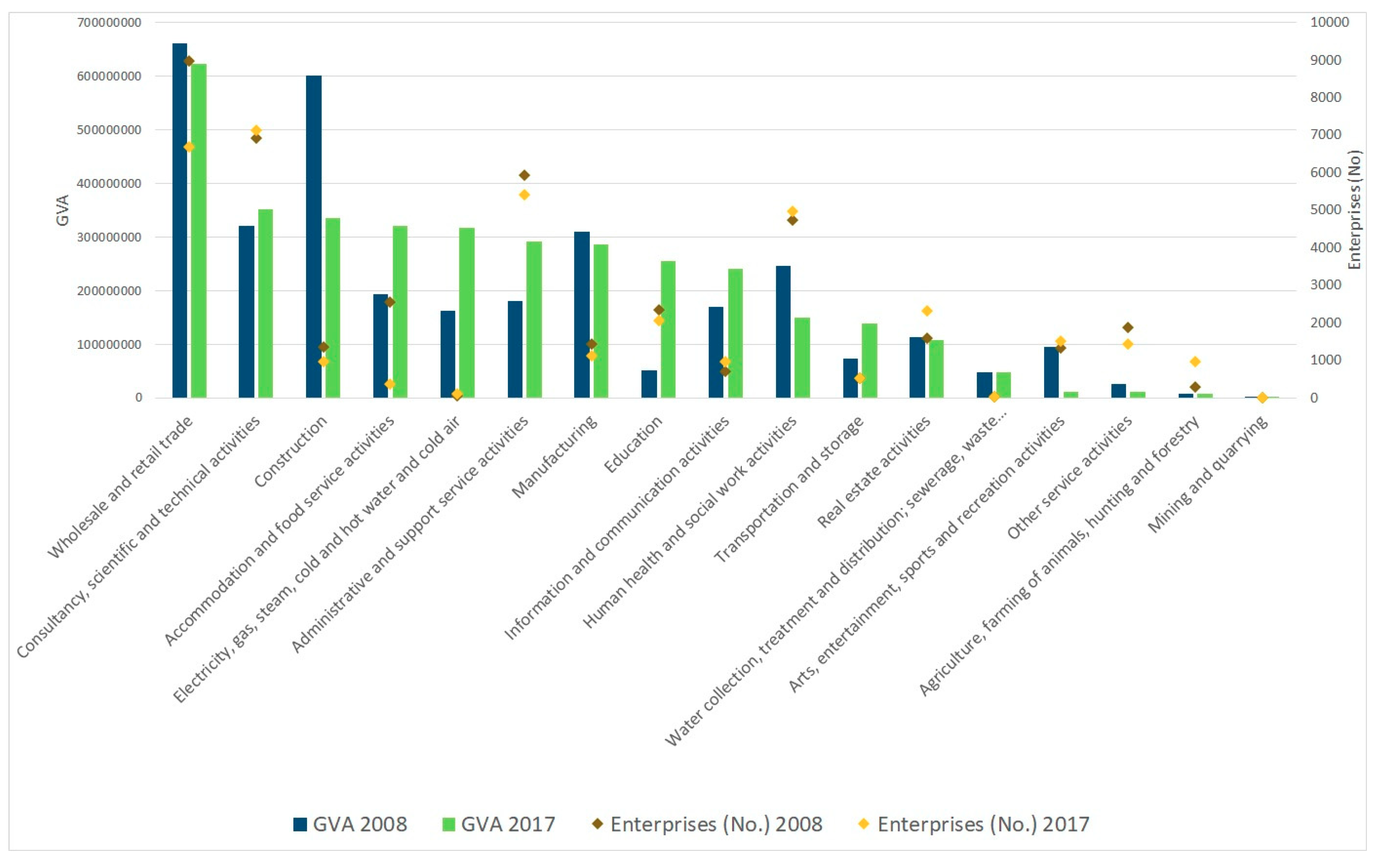

4.1. The Transformations of Porto’s City Centre

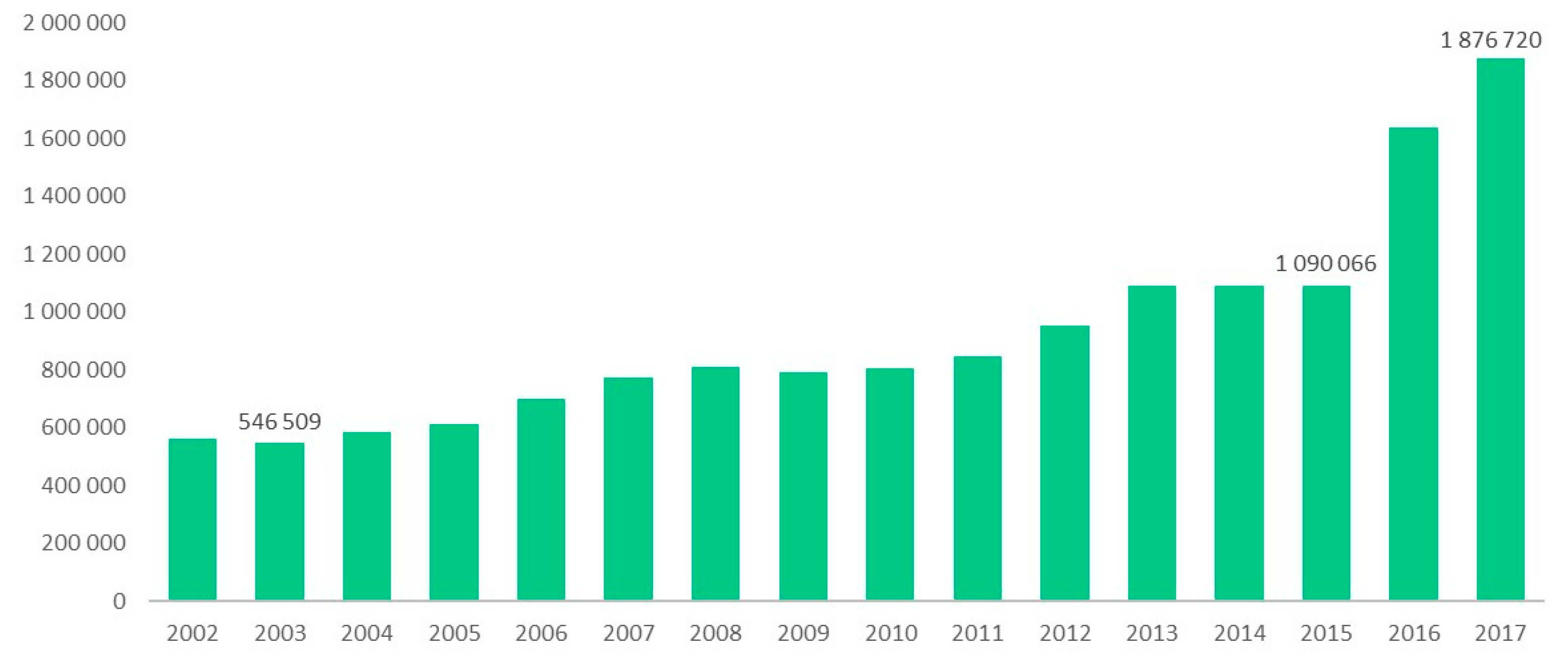

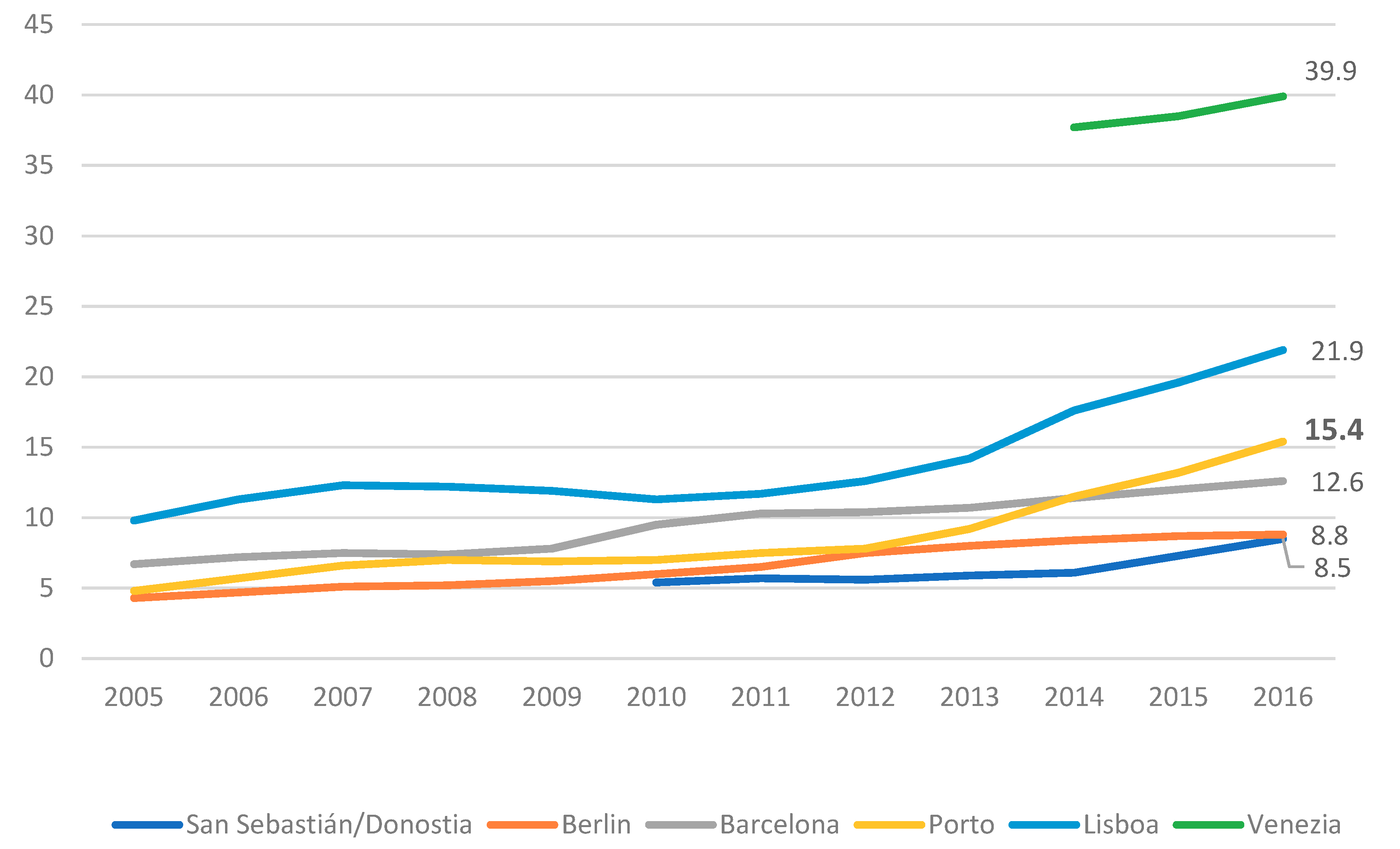

4.2. Tourism in Porto

5. Discussion: The Risks of Unsustainability and the Conflicts between Culture and Tourism

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gospodini, A. European cities in competition and the new ‘uses’ of urban design. J. Urban Des. 2002, 7, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. New State Spaces: Urban Governance and the Rescaling of Statehood; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R.L. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, T. The New Economy of the Inner City: Restructuring, Regeneration and Dislocation in the 21st Century Metropolis. Cities 2009, 21, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J. Cultural economy and the creative field of the city. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2010, 92, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, G.D. The ‘Bilbao effect’ from poor port to must-see city. Art Newsp. 2007, 184, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, B. Cultural Policy and Urban Regeneration in Western European Cities: Lessons from Experience, Prospects for the Future. Local Econ. 2004, 19, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. Hard-Branding the Art Museum—from Prado to Prada. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst & Young. Creating Growth: Measuring Cultural and Creative Markets in the EU; Ernst & Young: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, J.; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the Experience Economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rius Ulldemolins, J. Culture and authenticity in urban regeneration processes: Place branding in central Barcelona. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 3026–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, C.; Bianchini, F. The Creative City; Demos: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, A.P.; Scarnato, A.; Russo, A.P. “Barcelona in common”: A new urban regime for the 21st-century tourist city? tourist city? J. Urban Aff. 2017, 40, 455–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hernández, M.; de la Calle-Vaquero, M.; Yubero, C. Cultural heritage and urban tourism: Historic city centres under pressure. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W. Contribution of urban precincts to the urban economy. In City Spaces-Tourist Places; Hayllar, B., Griffin, T., Edwards, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 169–200. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.J. The Cultural Economy of Cities. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1997, 21, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troitiño Vinuesa, M.Á. El turismo en las ciudades históricas. Polígonos 1995, 5, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.; Chamusca, P.; Fernandes, J.; Pinto, J.; Chamusca, P. Gentrification in Porto: Floating city users and internationally-driven urban change. Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Impact of Culture on Tourism. 2009. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/tourism/theimpactofcultureontourism.htm (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- Richards, G. Cultural Tourism in Europe; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pred, A. Place as historically contingent process: Structuration and the time-geography of becoming places. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1984, 74, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, M.D.A. Sobre a memória das cidades. Rev. Territ. 1998, 3, 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, D. Possessed by the Past: The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.K. Tourism, Culture and Regeneration; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Paulauskaite, D.; Powell, R.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.; Morrison, A.M. Living like a local: Authentic tourism experiences and the sharing economy. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidon, E.S. The Fantasy of Authenticity: Touring with Lacan. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Future Foundation. Millennial Traveller Report. Why Millennials Will Shape the Next 20 Years of Travel. 2016. Available online: https://www.foresightfactory.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Expedia-Millennial-Traveller-Report-Final.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Judd, D.R.; Fainstein, S.S. The Tourist City; Yale University Press: New Haven, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Novy, J.; Colomb, C. Urban tourism and its discontents: An introduction. In Protest and Resistance in the Tourist City; Colomb, C., Novy, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- McCann, E.; Ward, K. Mobile Urbanism: Cities and Policymaking in the Global Age; University of Minnesota Press: Minnesota, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannides, D.; Petridou, E. Contingent neoliberalism and urban tourism in the United States. In Neoliberalism and the Political Economy of Tourism; Mosedale, J., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau, P.; François, H.; Bensahel, L. Fin (?) et Confins du Tourisme: Interroger le Statut et les Practiques de la Récréation Contemporaine; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). Princípios de Valletapara a Salvaguarda Gestão das Cidades Históricas e Áreas Urbanas; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, J.; Pine, J. Authenticity: What Consumers Really Want; Harvard Business Press: Harvard, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkster, F.M. When the spell is broken: Gentrification, urban tourism and privileged discontent in the Amsterdam canal district. Cult. Geogr. 2017, 24, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Economics and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Cultural Capital. J. Cult. Econ. 1999, 23, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, K.; Cros, H.; Li, W. The search for World Heritage brand awareness beyond the iconic heritage: A case study of the Historic Centre of Macao. J. Herit. Tour 2012, 7, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capello, R.; Perucca, G. Cultural Capital and Local Development Nexus: Does the Local Environment Matter? In Socioeconomic Environmental Policies and Evaluations in Regional Science. New Frontiers in Regional Science: Asian Perspectives; Shibusawa, H., Sakurai, K., Mizunoya, T., Uchida, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Licciardi, G.; Amirtahmasebi, R. The Economics of Uniqueness: Investing in Historic City Cores and Cultural Heritage Assets for Sustainable Development; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, N.; Kangas, A.; Beukelaer, C. Cultural policies for sustainable development: Four strategic paths. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2017, 23, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Culturally sustainable development: Theoretical concept or practical policy instrument? Int. J. Cult. Policy 2017, 23, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Global Report on Culture for Sustainable Urban Development Heritage and Creativity Culture. Available online: http://openarchive.icomos.org/1816/1/245999e.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2019).

- Sans, A.A.; Quaglieri, A. Unravelling Airbnb: Urban Perspectives from Barcelona. In Reinventing the Local in Tourism: Producing, Consuming and Negotiating Place; Russo, P., Richards, G., Eds.; Channel View: London, UK, 2016; pp. 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- Minoia, P. Venice reshaped? Tourist gentrification and sense of place. In Tourism in the City; Bellini, N., Pasquinelli, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gant, A.C. Holiday Rentals: The New Gentrification Battlefront. Sociol. Rese. Online 2016, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestegás, I.; Lois-González, R.C.; Seixas, J. The global rent gap of Lisbon’s historic centre. Sustain. City 2018, 13, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gant, A.C. Tourism and commercial gentrification. In The Ideal City: Between Myth and Reality, Representations, Policies, Contradictions and Challenges for Tomorrow’s Urban Life, Proceedings of the RC21 International Conference, Urbino, Italy, 27–29 August 2015; Urbino University: Urbino, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sequera, J.; Nofre, J. Urban activism and touristification in Southern Europe. In Contemporary Left-Wing Activism Vol. 2: Democracy, Participation and Dissent in a Global Context; Roberts, J.M., Ibrahim, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Tunbridge, J.E. The Tourist-Historic City; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Troitiño Vinuesa, M.Á.; Troitiño Torralba, L. Visión territorial del patrimonio y sostenibilidad del turismo. Boletín la Asoc. Geógrafos Españ. 2018, 78, 212–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, M. From overtourism to sustainability: A research agenda for qualitative tourism development in the Adriatic, Heidelberg University. MPRA Paper No 92213. 2019. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/92213/ (accessed on 24 August 2019).

- Duignan, M. ‘Overtourism’? Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions: Cambridge Case Study: Strategies and Tactics to Tackle Overtourism. In ‘Overtourism’? Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions; United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). População Residente (N.o) por Local de Residência (NUTS–2013), Sexo e Grupo Etário; Anual. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&contecto=pi&indOcorrCod=0008273&selTab=tab0> (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- Balsas, C.J.L. Local Economy City Centre Regeneration in the Context of the 2001 European Capital of Culture in Porto, Portugal. Local Econ. 2004, 18, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.A.R. A cidade, os municípios e as políticas. Sociol. Rev. Fac. Let. Univ. Porto 2017, 13, 227–251. [Google Scholar]

- Balsas, C.J.L. City Centre Revitalization in Portugal: A Study of Lisbon and Porto City Centre Revitalization in Portugal: A Study of Lisbon and Porto. J. Urban Des. 2007, 12, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, N.; Burns, M. The impacts of urban regeneration companies in Portugal: The case of Porto Vivo SRU. Adv. Urban Rehabil. Sustain. 2010, 9, 104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Porto Vivo Sociedade de Reabilitação Urbana da baixa Portuense. Porto Vivo Masterplan. Available online: http://www.portovivosru.pt/pt/area-de-atuacao/enquadramento (accessed on 24 March 2019).

- Fernandes, J.; Chamusca, P. Novos tempos, dinâmicas e desafios no centro do Porto. In Brasil e Portugal Vistos Desde as Cidades. As Cidades Vistas Desde o seu Centro; Sposito, M.E., Rio Fernandes, J.A., Eds.; Cultura Académica: São Paulo, Brazil, 2018; pp. 265–291. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, J.A. Area-based initiatives and urban dynamics. The case of the Porto city centre. Urban Res. Pract. 2011, 4, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, R.; Alves, S. Models of urban requalification under neoliberalism and austerity: The case of Porto. In Spaces of Dialogue for Places of Dignity: Fostering the European Dimension of Planning, Proceedings of the AESOP Annual Congress’1; Marques da Costa, E., Morgado, S., Cabral, J., Eds.; Universidade de Lisboa: Lisbon, Potugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Historic Centre of Oporto, Luiz I Bridge and Monastery of Serra do Pilar. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/pg.cfm?cid=31&id_site=755&l=en (accessed on 6 May 2019).

- Ritzer, G.; Liska, A. “McDisneyization” and “Post-tourism”. In Touring Cultures: Transformations of Travel and Theory; Rojek, C., Urry, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 96–109. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS-PORTUGAL. Comissão Nacional Portuguesa do Conselho Internacional dos Monumentos e Sítios. In Technical Evaluation Report on the Conservation State of UNESCO; Historical Centre of Oporto, Luiz I Bridge and Monastery of Serra do Pilar: Lisboa, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Turismo do Porto e Norte de Portugal. Estratégia de Marketing Turístico do Porto e Norte de Portugal. Horizonte 2015–2020. Available online: https://estrategia.turismodeportugal.pt/content/plano-de-marketing-tur%C3%ADstico-porto-e-norte (accessed on 6 May 2019).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Passageiros Embarcados (N.o) nos Aeroportos por Localização Geográfica, Tipo de Tráfego e Natureza do Tráfego, Mensal. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&contecto=pi&indOcorrCod=0000861&selTab=tab0 (accessed on 6 May 2019).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Capacidade de Alojamento nos Estabelecimentos Hoteleiros por 1000 Habitantes (N.o) por Localização Geográfica (NUTS—2013). Anual. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&indOcorrCod=0008784&contexto=bd&selTab=tab2 (accessed on 26 May 2019).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE) Hóspedes (N.o) nos Estabelecimentos Hoteleiros por Localização Geográfica (NUTS—2013) e Tipo (Estabelecimento Hoteleiro), Mensal. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&indOcorrCod=0001817&contexto=bd&selTab=tab2> (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- PORDATA. Average Stay in Tourist Accommodations: Total, Residents and Non-Residents. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/en/Municipalities/Average+stay+in+tourist+accommodations+total++residents+and+non+residents-758 (accessed on 26 May 2019).

- Eurostat. Culture and Tourism—Cities and Greater Cities. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/urb_ctour (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Porto’s Official Tourism Plan. Available online: http://www.visitporto.travel/Lists/ISSUUDocumentos/mapa_por.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Fernandes, J.A.R.; Carvalho, L.; Chamusca, P.; Mendes, T. O Porto e a Airbnb; Book Cover Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Valor Médio dos Prédios Transaccionados (€/N.o) por Localização Geográfica (NUTS—2013) e Tipo de Prédio, Anual. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&indOcorrCod=0008760&contexto=bd&selTab=tab2&xlang=pt (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Turismo de Portugal. Registo Nacional do Alojamento Local. Available online: https://www.alesclarecimentos.pt/legal/registo-nacional-do-al/> (accessed on 6 May 2019).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Valor Mediano das Vendas por m2 de Alojamentos Familiares (€) por Localização Geográfica (Cidade) e Categoria do Alojamento Familiar, Trimestral—INE, Estatisticas de Preços da Habitação ao Nível Local. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&contecto=pi&indOcorrCod=0009492&selTab=tab0&xlang=en (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Valor Acrescentado Bruto (€) das Empresas por Localização Geográfica (NUTS—2013) e Atividade Económica (Subclasse—CAE Rev. 3); Anual—INE, Sistema de Contas Integradas das Empresas. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&indOcorrCod=0008485&contexto=bd&selTab=tab2&xlang=PT (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Sequera, J.; Nofre, J. Shaken, not stirred: New debates on touristification and the limits of gentrificatio. City 2018, 22, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei n.º 42/2017 de 14 de Junho. Diário da República n.º 114/2017 Série I de 2017-06-14, 2993–2996. Available online: https://data.dre.pt/eli/lei/42/2017/06/14/p/dre/pt/html (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Der Spiegel. How Tourists Are Destroying the Places They Love. Available online: https://www.spiegel.de/international/paradise-lost-tourists-are-destroying-the-places-they-love-a-1223502.html (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- The Guardian “No One Likes Being a Tourist”: The Rise of the Anti-Tour. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/jan/28/no-one-likes-being-a-tourist-the-rise-of-the-anti-tour (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Manuel Sousa. Casa Oriental. Available online: https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ficheiro:Casa_Oriental_(Porto).JPG (accessed on 10 June 2019).

- Hitters, E. Porto and Rotterdam as European Capitals of Culture: Toward the festivalization of urban cultural policy. In Cultural Tourism: Global and Local Perspectives; Richards, G., Ed.; The Haworth Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 281–301. [Google Scholar]

- Mota Santos, P. Tourism and the critical cosmopolitanism imagination: “The Worst Tours” in a European World Heritage city. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 25, 943–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is Overtourism Overused? Understanding the Impact of Tourism in a City Context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novy, J. Urban tourism as a bone of contention. Four explanatory hypotheses and a caveat. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Guardian. “We Must Act Now”: Netherlands Tries to Control Tourism Boom. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/may/06/we-must-act-now-netherlands-tries-to-control-tourism-boom (accessed on 24 August 2019).

- Público. Câmara do Porto só travará Alojamento Local Quando Houver Regulamento. Available online: https://www.publico.pt/2019/06/04/local/noticia/camara-porto-so-travara-alojamento-local-regulamento-1875339 (accessed on 23 August 2019).

- Bhandari, K. Touristification of cultural resources: A case study of Robert Burns. Tourism 2008, 56, 283–293. [Google Scholar]

- NBTC Holland Marketing, Intell & Insight. Tourism in Perspective. Available online: https://nbtcmagazine.maglr.com/en_US/15394/217245/tourism_in_perspective_july_2019.html (accessed on 24 May 2019).

| Type of Unit | July ‘12 | July ‘14 | July ‘16 | July ‘18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food products | 94 | 100 | 99 | 98 |

| Personal products | 480 | 466 | 461 | 399 |

| Home products | 123 | 119 | 97 | 86 |

| Beauty and personal care products | 87 | 97 | 92 | 79 |

| Sports and culture | 201 | 247 | 218 | 196 |

| Professional equipment | 27 | 35 | 37 | 33 |

| Non-specialized retail | 102 | 91 | 93 | 95 |

| Hybrids | 16 | 19 | 31 | 36 |

| Construction and bricolage | 70 | 47 | 38 | 31 |

| Fuel and transports | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Retail (total) | 1202 | 1222 | 1167 | 1053 |

| Coffeehouses and restaurants | 406 | 454 | 523 | 568 |

| Accommodation/hotels | 79 | 102 | 141 | 196 |

| Hotel/Catering (Total) | 485 | 556 | 664 | 764 |

| Retail/Hotel/Catering (Total) | 1687 | 1778 | 1831 | 1817 |

| Shopping centres | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Other services | 269 | 272 | 280 | 277 |

| Retail and services (Total) | 1964 | 2058 | 2119 | 2102 |

| Empty | 829 | 734 | 657 | 707 |

| Total | 2793 | 2792 | 2776 | 2809 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gusman, I.; Chamusca, P.; Fernandes, J.; Pinto, J. Culture and Tourism in Porto City Centre: Conflicts and (Im)Possible Solutions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205701

Gusman I, Chamusca P, Fernandes J, Pinto J. Culture and Tourism in Porto City Centre: Conflicts and (Im)Possible Solutions. Sustainability. 2019; 11(20):5701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205701

Chicago/Turabian StyleGusman, Inês, Pedro Chamusca, José Fernandes, and Jorge Pinto. 2019. "Culture and Tourism in Porto City Centre: Conflicts and (Im)Possible Solutions" Sustainability 11, no. 20: 5701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205701

APA StyleGusman, I., Chamusca, P., Fernandes, J., & Pinto, J. (2019). Culture and Tourism in Porto City Centre: Conflicts and (Im)Possible Solutions. Sustainability, 11(20), 5701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205701