Are People Ready to Entrust Their Safety to an Autonomous Ambulance as an Alternative and More Sustainable Transportation Mode?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

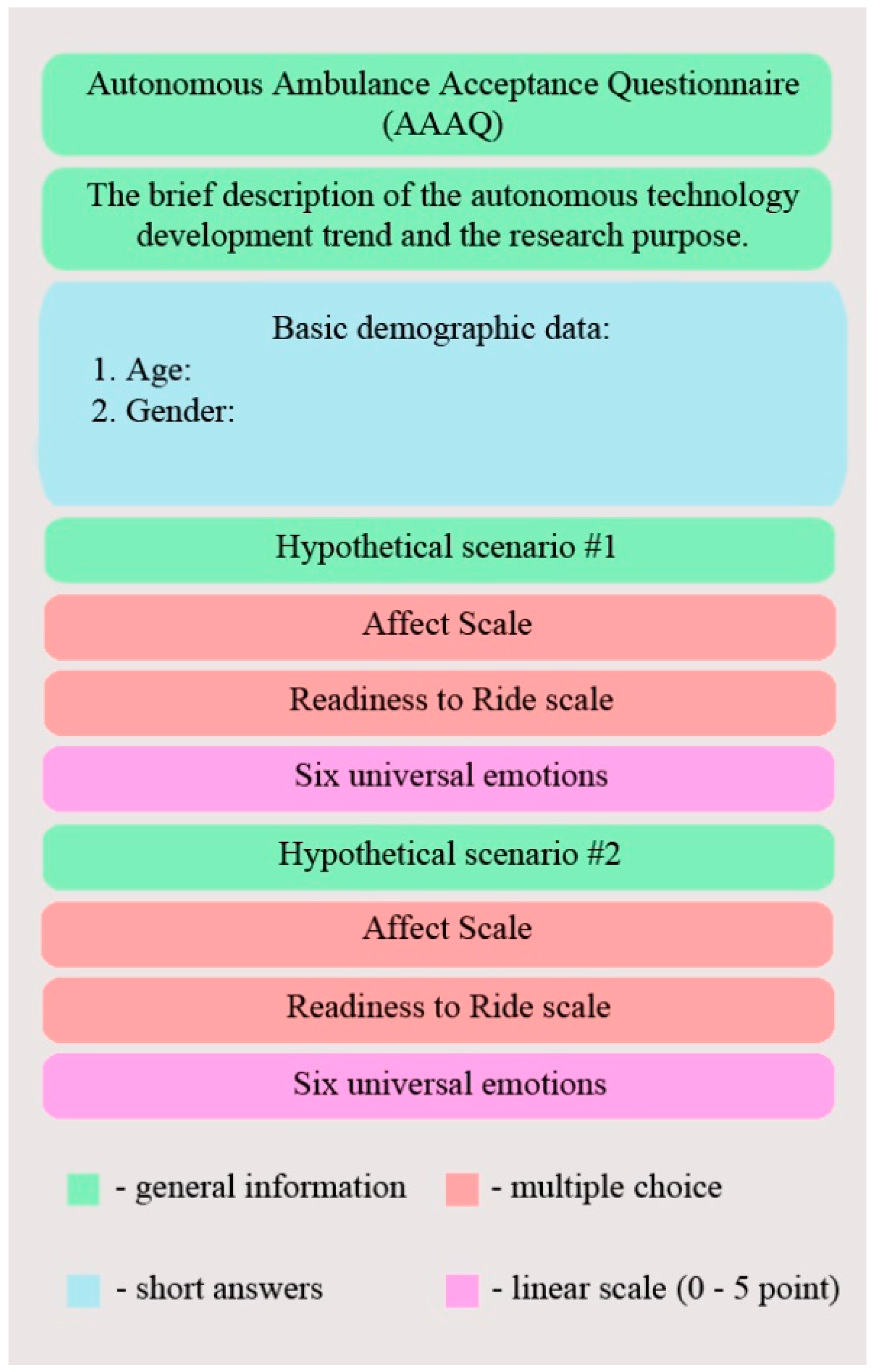

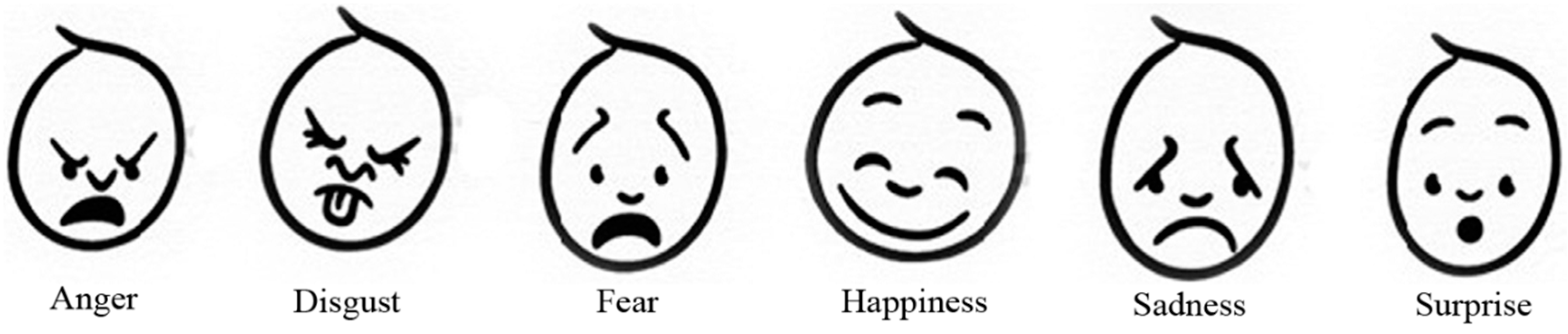

3.2. Materials and Procedure

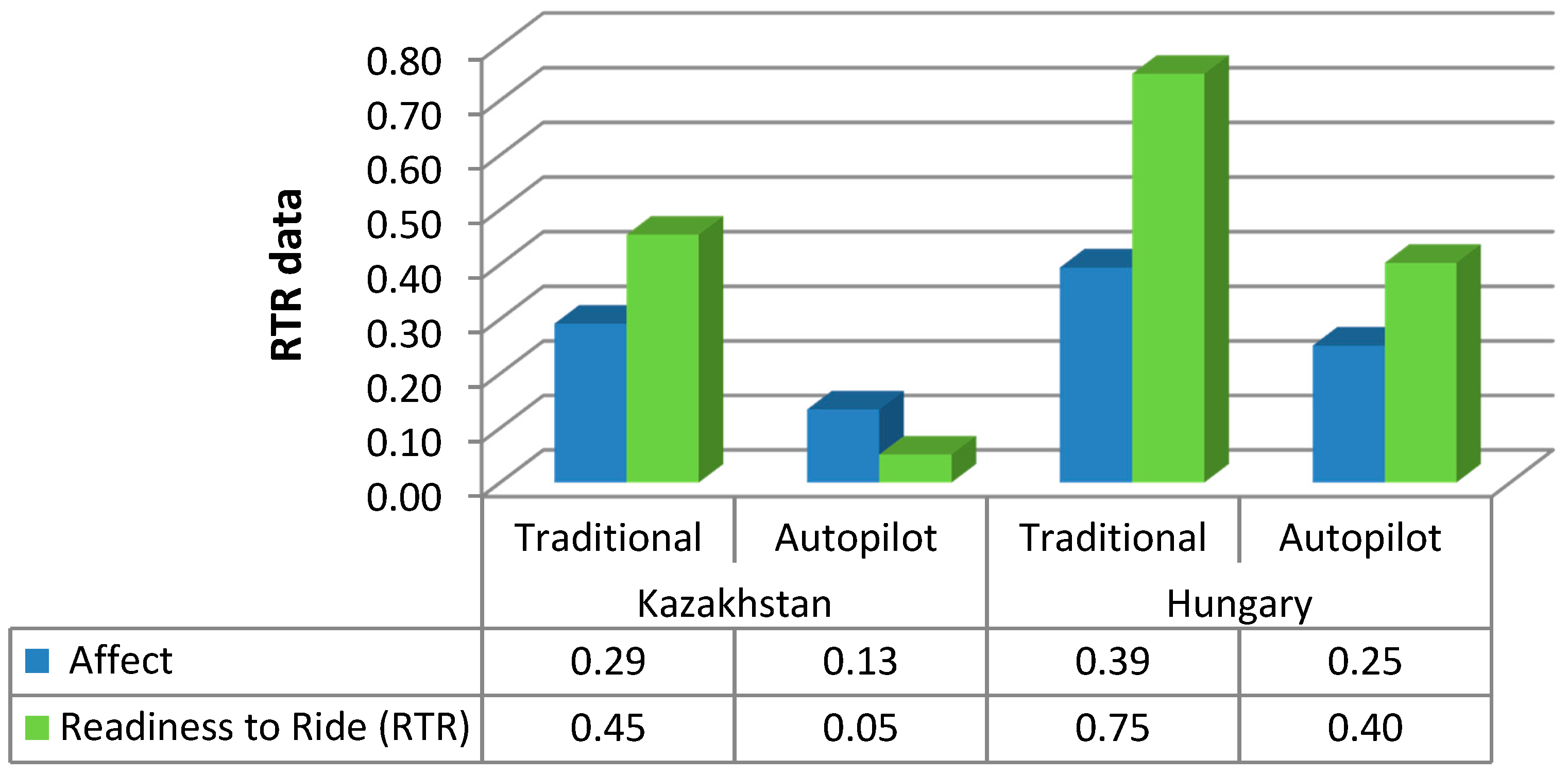

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. ‘t-Test’: Paired Two Samples for Mean Values (Hungary)

4.2. ‘t-Test’: Paired Two Samples for Mean Values (Kazakhstan)

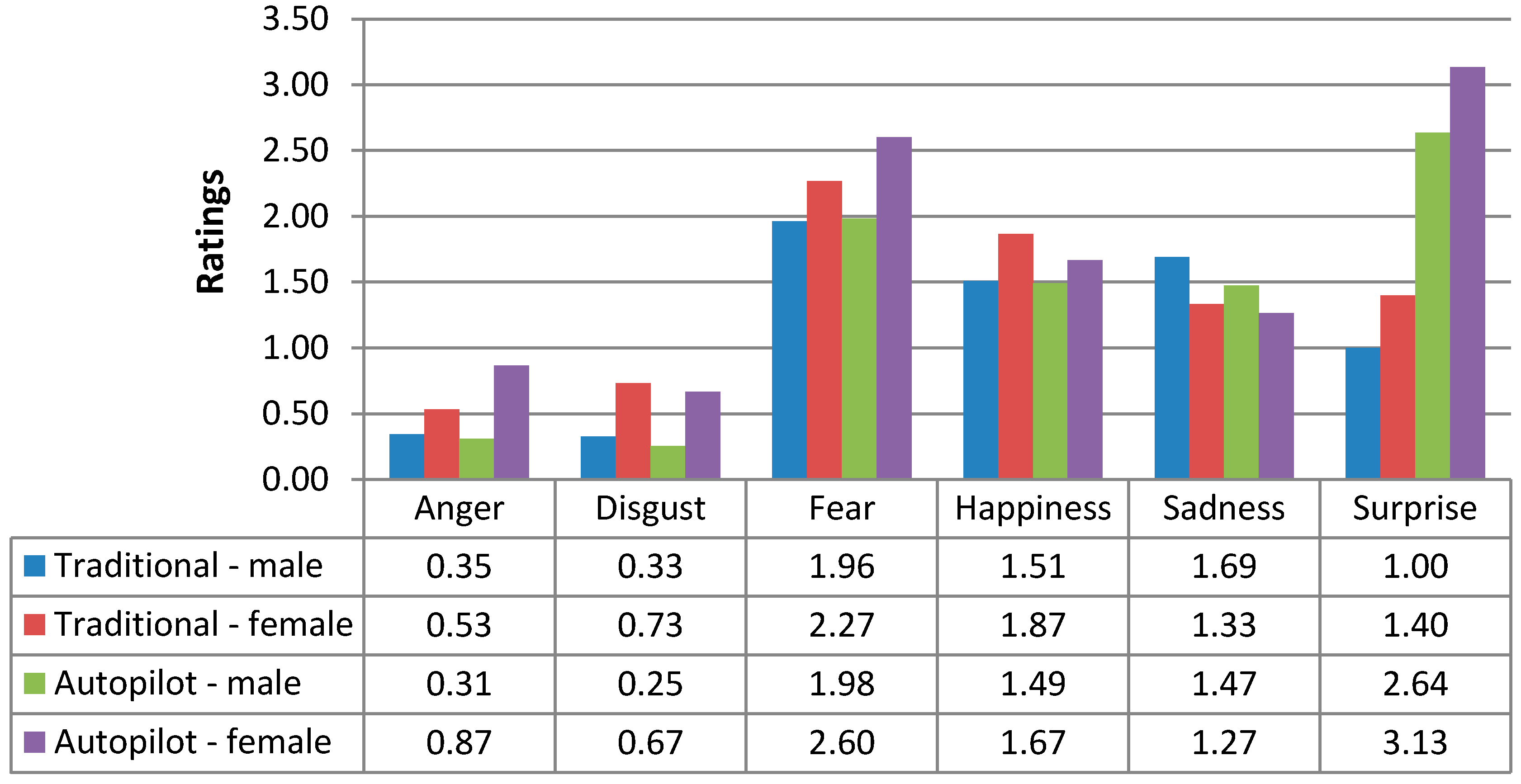

4.3. Two-Way ‘ANOVA’ Analysis (Hungary)

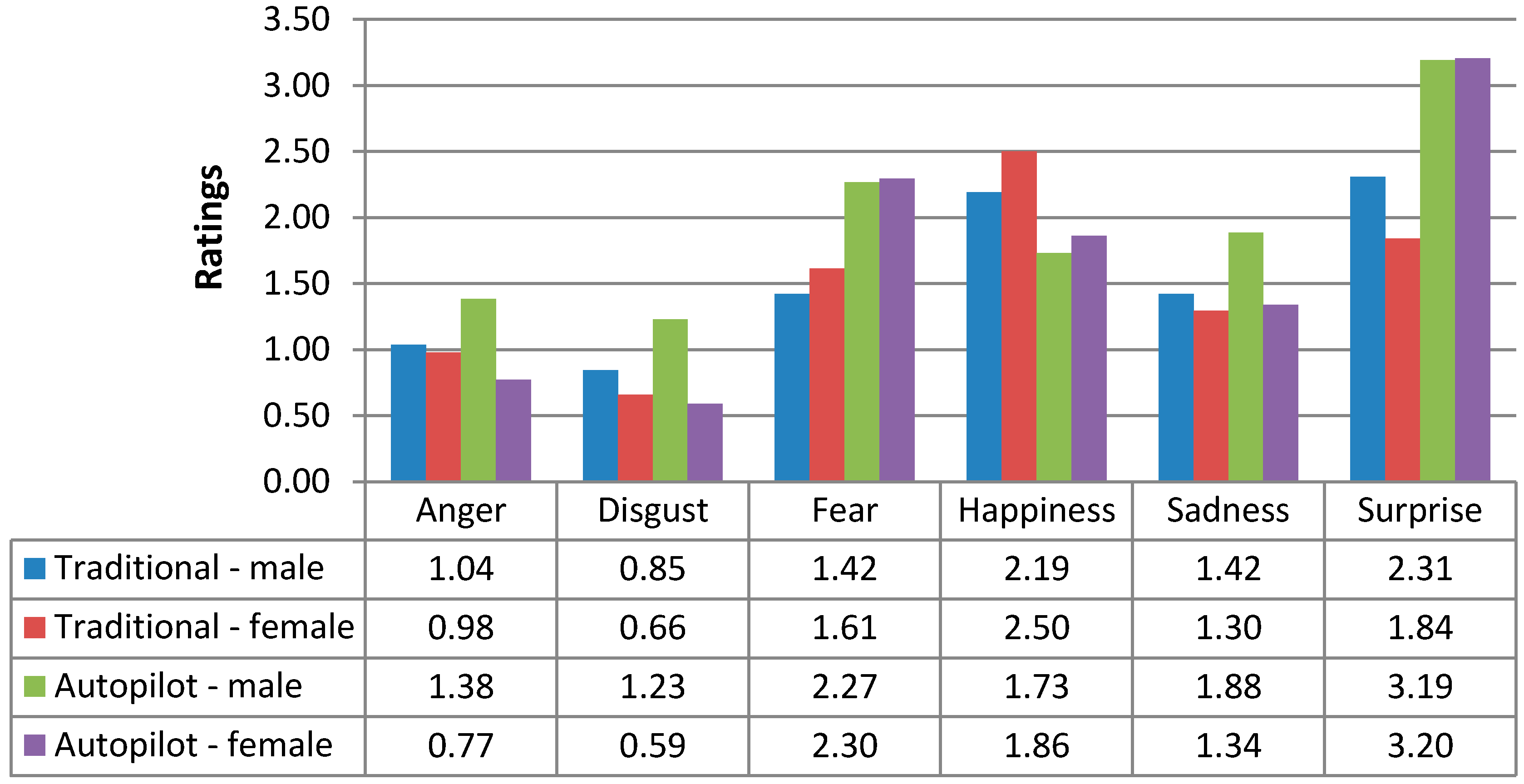

4.4. Two-Way ‘ANOVA’ Analysis (Kazakhstan)

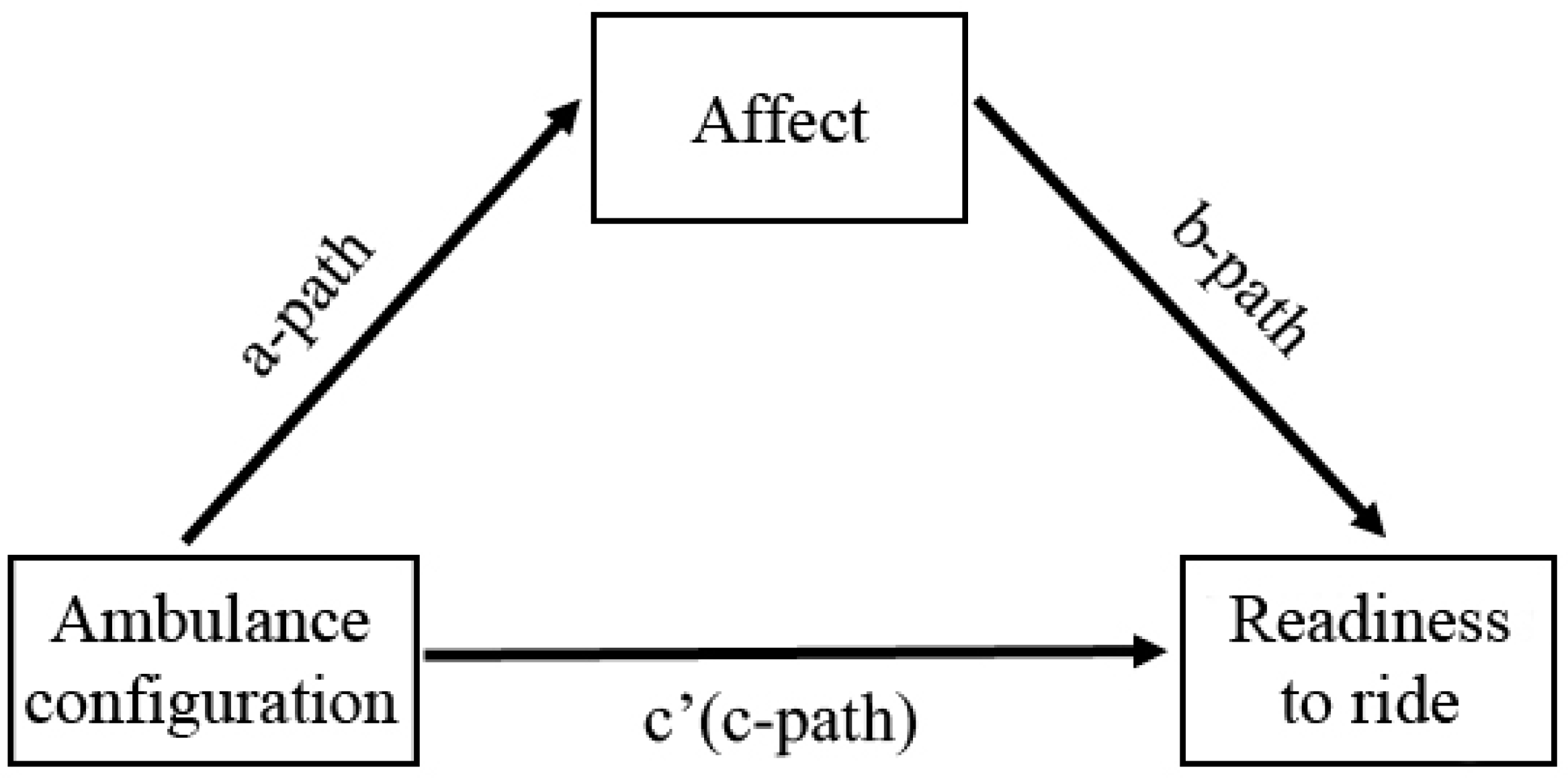

4.5. Mediation Analysis (Hungary)

4.6. Mediation Analysis (Kazakhstan)

4.7. General Discussion

5. Release of Limitations, Outlook

6. Conclusions

- A questionnaire survey to measure users’ readiness to ride in self-driving ambulances.

- Analysis of the data received from respondents according to several aspects.

- People are obviously less ready to ride in, and have more negatory feelings toward an autonomous vehicle in contrast to a traditional one.

- Participants from Kazakhstan are less ready to travel in both traditional and driverless ambulance modes than Hungarian consumers.

- Participants from Kazakhstan demonstrated more negative emotions towards both conditions than Hungarian consumers.

- There is a statistically substantial distinction in readiness to ride according to mode and a nonsignificant one in readiness to ride according to gender.

- The variance in the dependent variable (RTR) cannot be attributed to the interaction between mode and gender.

- Consumers’ emotions did not play a key role in their responses regarding their readiness to ride.

- None of the six universal emotions were found as a mediator during the mediation analysis, neither for males nor females.

- Extend and replicate the study involving participants with different ages and occupations to figure out whether results are the same or what the differences are.

- Study the Emergency Medical Service (EMS) providers applying the same approach.

- Proceed with the research by elaboration and investigation of more complex scenarios.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szél, D. Hungarian Ambulance Service Forces Drivers to Perform Nurse Duties. Daily News Hungary. 2018. Available online: https://dailynewshungary.com/hungarian-ambulance-service-forces-drivers-to-perform-nurse-duties/ (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Tettamanti, T.; Varga, I.; Szalay, Z. Impacts of Autonomous Cars from a Traffic Engineering Perspective. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2016, 44, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szalay, Z.; Nyerges, Á.; Hamar, Z.; Hesz, M. Technical Specification Methodology for an Automotive Proving Ground Dedicated to Connected and Automated Vehicles. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2017, 45, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalay, Z.; Tettamanti, T.; Esztergár-Kiss, D.; Varga, I.; Bartolini, C. Development of a Test Track for Driverless Cars: Vehicle Design, Track Configuration, and Liability Considerations. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2018, 46, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.M.; Kalra, N.; Stanley, K.D.; Sorensen, P.; Samaras, C.; Oluwatola, O. Autonomous Vehicle Technology: A Guide for Policymakers; Rand Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.-H.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Malmborg, C.J. Design models for unit load storage and retrieval systems using autonomous vehicle technology and resource conserving storage and dwell point policies. Appl. Math. Model. 2007, 31, 2332–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connected and Autonomous Vehicles: The Future? 2017. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201617/ldselect/ldsctech/115/11505.htm#footnote-224 (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- South Central Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust (SCAS). SCAS Joins UK’s Largest Autonomous and Connected Vehicle Project. 2019. Available online: https://www.scas.nhs.uk/scas-joins-uks-largest-autonomous-and-connected-vehicle-project/ (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Hughes, A.; Gregory, M.; Joseph, D.; Sonesh, S.C.; Marlow, S.L.; Lacerenza, C.; Benishek, L.E.; King, H.B.; Salas, E. Saving lives: A meta-analysis of team training in healthcare. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, M.A.; Mathieu, J.E.; Zaccaro, S.J. A Temporally Based Framework and Taxonomy of Team Processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, N. A national perspective on ambulance crashes and safety. EMS World 2015, 44, 91–92. [Google Scholar]

- Jaynes, C. The price of safety: Comparing the return on investment in safe driving systems. JEMS J. Emerg. Med. Serv. 2016, 41, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, P.; Huang, H.; Ran, B.; Zhan, F.; Shi, Y. Exploring the Factors Affecting Mode Choice Intention of Autonomous Vehicle Based on an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior—A Case Study in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickens, C.D.; Hollands, J.G.; Banbury, S.; Parasuraman, R. Engineering Psychology and Human Performance; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2015; p. 544, ISBN 1317351320, 9781317351320. [Google Scholar]

- Geels-Blair, K.; Rice, S.; Schwark, J. Using system-wide trust theory to reveal the contagion effects of automation false alarms and misses on compliance and reliance in a simulated aviation task. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 2013, 23, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, R.; Riley, V. Humans and automation: Use, misuse, disuse, abuse. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 1997, 39, 230–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S.; Geels, K. Using system-wide trust theory to make predictions about dependence on four diagnostic aids. J. Gen. Psychol. 2010, 137, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, S. Examining- and multiple-process theories of trust in automation. J. Gen. Psychol. 2009, 136, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes, D.; Csiszár, C.; Zarkeshev, A. User expectations towards mobility services based on autonomous vehicle. In Proceedings of the 8th International Scientific Conference CMDTUR, Žilina, Slovakia, 4–5 October 2018; pp. 7–15, ISBN 978-80-554-1485-0. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, M. Trust and suspicion. J. Confl. Resolut. 1958, 2, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, C.C.; Wilson, R.K. Is trust a risky decision? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2004, 55, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergeneli, A.; Saglam, G.; Metin, S. Psychological empowerment and its relationship to trust in immediate managers. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, B.; Nass, C. The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People and Places; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidis, M.; Happee, R.; Winter, J.C.F. Public opinion on automated driving: Results of an international questionnaire among 5000 respondents. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2015, 32, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anania, E.C.; Rice, S.; Walters, N.W.; Pierce, M.; Winter, S.R.; Milner, M.N. The effects of positive and negative information on consumers’ willingness to ride in a driverless vehicle. Transp. Policy 2018, 72, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, R.; Brown, M.; Gysler, M.; Brachinger, H.W. Financial decision-making: Are women really more risk-averse? Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.; Ansic, D. Gender differences in risk behaviour in financial decision-making: An experimental analysis. J. Econ. Psychol. 1997, 18, 605–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, J.P.; Miller, D.C.; Schafer, W.D. Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N. Emotion, cognition, and decision making. Cogn. Emot. 2000, 14, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A. The role of emotion in decision-making: Evidence from neurological patients with orbitofrontal damage. Brain Cogn. 2004, 55, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayegh, L.; Anthony, W.P.; Perrewe, P.L. Managerial decision-making under crisis: The role of emotion in an intuitive decision process. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2004, 14, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 17, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V.; Hagar, J.C. Facial Action Coding System Investigators Guide; Research Nexus: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P.; Sorenson, E.R.; Friesen, W.V. Pan-cultural elements in facial displays of emotion. Science 1969, 164, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S.; Winter, S.R. Which emotions mediate the relationship between type of pilot configuration and willingness to fly? Aviat. Psychol. Appl. Hum. Factors 2015, 5, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.R.; Rice, S.; Tamilselvan, G.; Tokarski, R. Mission-based citizen views on UAV usage and privacy: An affective perspective. J. Unmanned Veh. Syst. 2016, 4, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Attaway, J.S. Atmospheric affect as a tool for creating value and gaining share of customer. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 49, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Cameron, M. The effects of the service environment on affect and consumer perception of waiting time: An integrative review and research propositions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1996, 24, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.C. Says who? How the source of price information and affect influence perceived price (un) fairness. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 44, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.R.; Rice, S.; Mehta, R. Aviation consumers’ trust in pilots: A cognitive or emotional function. Int. J. Aviat. Aeronaut. Aerosp. 2014, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.; Bisantz, A.M.; Drury, C.G. Foundations for an empirically determined scale of trust in automated systems. Int. J. Cogn. Ergon. 2000, 4, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, I.; Rice, S. Which emotions mediate the relationship between type of water recycling projects and likelihood of using green airports. Int. J. Sustain. Aviat. 2015, 1, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S.; Winter, S. A quick affect scale: Providing evidence for validity and reliability. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, Split, Croatia, 11–14 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, S.; Kraemer, K.; Mehta, R. Which emotion(s) mediate the relationship between mental illness and trust? Issues Soc. Sci. 2015, 3, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, 2nd ed.; A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781462534654. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, S.R.; Keebler, J.R.; Rice, S.; Mehta, R.; Baugh, B.S. Patient perceptions on the use of driverless ambulances: An affective perspective. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 58, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Hungary | Kazakhstan |

|---|---|---|

| Number of respondents | 70 | 70 |

| Age | ||

| M | 22.54 | 28.20 |

| SD | 2.95 | 7.54 |

| Mode | Hungary | Kazakhstan | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RTR scale | ‘Affect’ scale | RTR scale | ‘Affect’ scale | |

| Traditional | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.87 |

| Autopilot | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zarkeshev, A.; Csiszár, C. Are People Ready to Entrust Their Safety to an Autonomous Ambulance as an Alternative and More Sustainable Transportation Mode? Sustainability 2019, 11, 5595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205595

Zarkeshev A, Csiszár C. Are People Ready to Entrust Their Safety to an Autonomous Ambulance as an Alternative and More Sustainable Transportation Mode? Sustainability. 2019; 11(20):5595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205595

Chicago/Turabian StyleZarkeshev, Azamat, and Csaba Csiszár. 2019. "Are People Ready to Entrust Their Safety to an Autonomous Ambulance as an Alternative and More Sustainable Transportation Mode?" Sustainability 11, no. 20: 5595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205595

APA StyleZarkeshev, A., & Csiszár, C. (2019). Are People Ready to Entrust Their Safety to an Autonomous Ambulance as an Alternative and More Sustainable Transportation Mode? Sustainability, 11(20), 5595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205595