Leadership and Governance Tools for Village Sustainable Development in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Governance Tools and Leadership in the GNF

2.1. Resource Interdependency Theory and the “Activating” Tool

2.2. Network Theory and the “Framing” Tool

2.3. Decentered Theory of Networks and the “Mobilizing” Tool

3. Method and Data

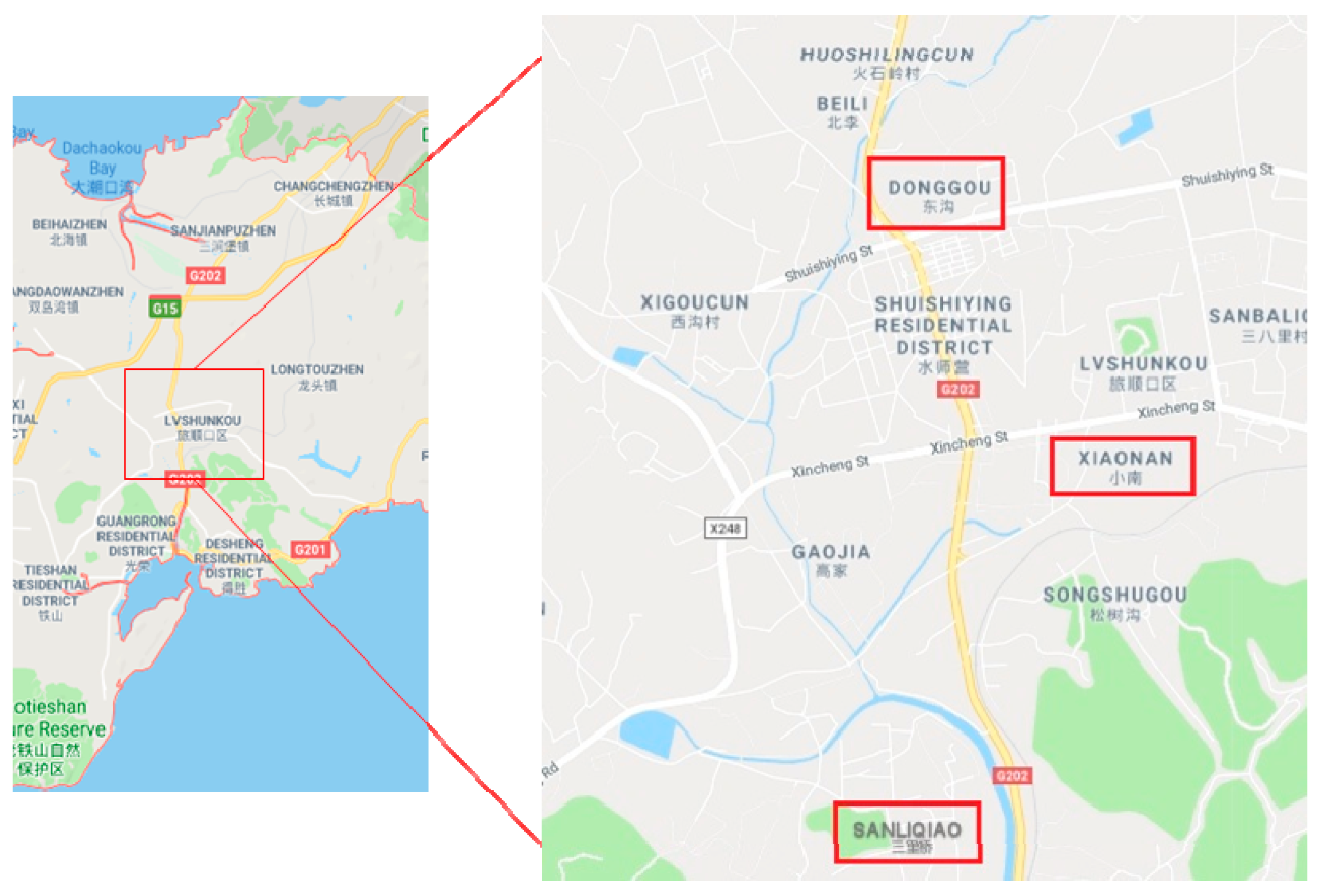

3.1. Process Tracing in a Single Deep Case Study

3.2. Case Selection

3.3. Data Collection

4. An Overview of Rural-Village Governance Networks in China

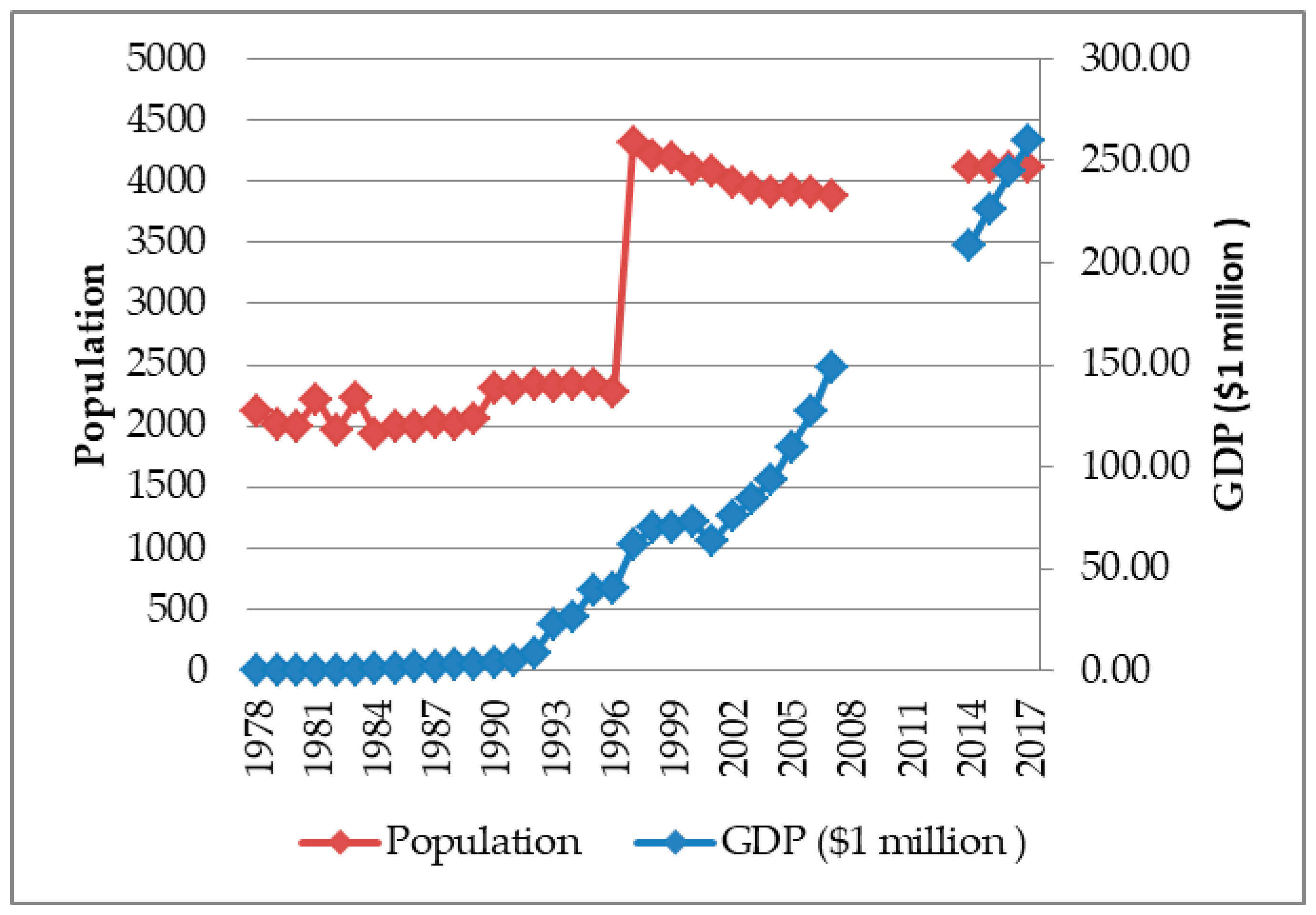

5. Development of Rural-Village Governance Networks in Xiaonan Village

5.1. Phase 1 (1978~1997): Xiaonan’s Early Governance Success and the District Government‘s First Effort to Enhance the Governance Network

5.1.1. The Formulation of Xiaonan Formal Rural-Village Governance Network

5.1.2. The Extension of Rural-Village Governance by Amalgamating Other Villages

5.1.3. Dose the “Activating” Tool Contribute to Better Governance Networks?

5.2. Phase 2 (1997~2007): Privatization and Challenges Posed to Village-Governance Networks by Expropriation

5.2.1. Privatization of Village Resources

5.2.2. Village Expropriation

5.2.3. Does the “Framing” Tool Contribute to Better Governance Networks?

5.3. Phase3 (2007~2014): Xiaonan’s Efforts to Develop Governance Networks by Building Partnerships with Multi-Level Governmental Sectors and Establishing New Village-Owned Enterprise

5.3.1. Partnership with Multi-Level Governmental Sectors

5.3.2. The Development of New Village-Owned Enterprises

5.3.3. Does the “Mobilizing” Tool Contribute to Governance Network Sustainable Development?

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Awarded Time | List of titles awarded | Awarding units |

| 2008.03.06 | “Sanba” red flag collective of Lvshun kou district | Lvshunkou district women’s federation |

| 2009.01.10 | 2006–2009 “two ‘a’ excellent” advanced party organization of Shuishiying street | Shuishiying street party working committee |

| 2010.3.3 | Honorary title of female demonstration village in Lvshunkou district | Lvshunkou district women’s federation |

| 2010.03.03 | 2008–2009 advanced collective of Dalian women’s federation system | Dalian women’s federation |

| 2010.09.25 | Advanced afforestation village in Dalian in 2010 | Dalian people’s government |

| 2010.9.25 | 2009 annual economic top ten villages of Lvshunkou district | People’s government of Lvshunkou district |

| 2010.9.25 | 2009 new rural construction demonstration village of Lvshunkou district | People’s government of Lvshunkou district |

| 2011.03.24 | The advanced collective of population family planning in Lvshunkou district from 2009 to 2010 | Lvshunkou district family planning bureau |

| 2011.12.31 | “Warm home” in Lushun district | Lvshunkou district women’s federation |

| 2011.6.28 | Advanced primary party organization in Lvshunkou district from 2009 to 2011 | People’s government of Lvshunkou district |

| 2011.5 | Culture village of Dalian | Dalian spiritual civilization construction steering committee |

| 2012.5.8 | Modern agricultural women’s demonstration base of Dalian | City Shuangxue Shuangbi coordination group |

| 2012.2.3 | Advanced collective for women’s work and “top ten women’s homes” of Dalian | Dalian women’s federation |

| 2012,2 | Nanshan urban modern agriculture demonstration area | Dalian people’s government |

| 2013 | 2012 advanced unit of leisure agriculture and rural tourism | Dalian tourism work leading group |

| 2014.2.19 | Dalian advanced rural tourism unit | City tourism work leading group |

| 2015.10 | “Dream quest 2015 China’s most beautiful villages and towns” China’s most beautiful villages and towns civilization award | Shanghai first finance media co., LTD., China’s most beautiful village selection activities committee |

| 2015.12.18 | National 4A scenic spot | Liaoning tourism scenic spot quality evaluation committee |

| 2015.12 | National model of leisure agriculture and rural tourism | Ministry of agriculture, national tourism administration |

| 2015.12 | National agricultural science demonstration base | Ministry of finance, China association for science and technology |

| 2016.8 | Double support to build advanced units | Lvshunkou district Shuangyong Gongjian leading group |

| 2016 | Top 100 examples of China’s beautiful countryside in 2016 | The organizing committee of the promotion activity, China rural magazine office of the ministry of agriculture |

| 2016.3 | May 1st female model guard of Lvshunkou district | Lvshunkou district federation of trade unions |

| 2016.3.2 | 2015 advanced collective of Dalian association for science and technology | Dalian science and technology association |

| 2016.3.9 | Advanced youth league branch in Lushun district | Lvshunkou district youth league committee |

| 2016.6 | National advanced unit for popularizing science, benefiting farmers and prospering villages | Ministry of finance, China association for science and technology |

| 2016.6 | Marine battalion street outstanding primary party organization | party working committee of ShuiShiYing neighborhood |

| 2017.2.17 | 2016 rural tourism advanced unit | Dalian tourism work leading group |

| 2017.4 | Outstanding farm bookstore in Lvshun district | Lvshunkou district culture, sports, radio, film and television bureau |

| 2017.7.26 | Top 10 beautiful villages in Dalian in 2017 | Dalian rural economic committee, Dalian tourism development committee |

| 2017.3 | Outstanding new agricultural operators in Lvshun district from 2014 to 2016 | People’s government of Lvshunkou district |

| 2017.5 | 2016 Dalian advanced youth league branch | Dalian municipal committee of the communist youth league |

| 2018.5 | Outstanding youth league branch in Lvshunkou district | Lvshunkou district committee of the communist youth league |

| 2018.8 | Advanced unit of beautiful countryside construction in China | China new rural construction BBS organizing committee |

| 2018.9 | "Chinese farmers harvest festival" characteristic 100 villages | General office of the ministry of agriculture, rural areas and villages of China |

| 2018.9.25 | The most beautiful ancient town in Dalian in 2018 | Dalian rural economic committee, Dalian tourism development committee, Dalian cultural broadcasting film and television bureau, Dalian planning bureau |

| 2018.7.13 | The first group of Dalian research and learning travel base | Dalian tourism development committee, Dalian tourism association |

| 2018.9 | Beautiful countryside research institute creation base of Dalian | Dalian beautiful countryside research institute |

| 2018.9 | 2018 China’s most beautiful village rural revitalization model award | Shanghai first finance media co., LTD., China’s most beautiful village selection activities committee |

| 2018.11.3 | Ninth Yuan Qing Cup volleyball competition champion of Lvshunkou district | Lvshunkou district volleyball association |

| 2019.7 | The first batch of key rural tourism villages in China | Ministry of culture and tourism of the People’s Republic of China |

References

- Scharpf, F.W. Games real actors could play: Positive and negative coordination in embedded negotiations. J. Theor. Polit. 1994, 6, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. Understanding Governance: Policy Networks, Governance, Reflexivity and Accountability; Open University Press: London, UK, 1997; ISBN 0335197272. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. The governance narrative: Key findings and lessons from the ERC’s Whitehall Programme. Public Adm. 2000, 78, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, L.J.; Meier, K.J. CHAPTER 9 Networks, Hierarchies, and Public Management: Modeling the Nonlinearities. In Governance and performance: new perspectives; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; p. 263. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C. The Networked Polity: Regional Development in Western Europe. Governance 2000, 13, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legler, T.F. The Shifting Sands of Regional Governance: The Case of Inter-A merican Democracy Promotion. Polit. Policy 2012, 40, 848–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, E.; Koppenjan, J. Governance Network Theory: Past, Present and Future. Policy Politics 2012, 40, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemberton, S.; Goodwin, M. Rethinking the changing structures of rural local government–State power, rural politics and local political strategies? J. Rural Stud. 2010, 26, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulda, A.; Li, Y.; Song, Q. New strategies of civil society in China: A case study of the network governance approach. J. Contemp. China 2012, 21, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Luo, R.; Yi, H.; Shi, Y.; Rozelle, S. Project design, village governance and infrastructure quality in rural China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2013, 5, 248–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gusmano, M.K.; Cao, Q. An evaluation of the policy on community health organizations in China: Will the priority of new healthcare reform in China be a success? Health Policy 2011, 99, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Information Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China (IOSC). National Human Rights Action Plan of China (2009–2010). Chin. J. Int. Law 2009, 8, 741–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’toole, K. Community governance in rural Victoria: Rethinking grassroots democracy? Rural Soc. 2006, 16, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G.; Knollenberg, W.; Komorowski, A. The central role of leadership in rural tourism development: A theoretical framework and case studies. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1277–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, E.H. Governance and governance networks in Europe: An assessment of ten years of research on the theme. Public Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 505–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Warner, T.J.; Yang, D.L.; Liu, M. Patterns of Authority and Governance in Rural China: who’s in charge? Why? J. Contemp. China 2013, 22, 733–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, B.; Mayntz, R. Introduction: Studying policy networks. In Policy Networks: Empirical Evidence and Theoretical Considerations; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 1991; pp. 11–23. ISBN 3593344718. [Google Scholar]

- Kooiman, J. Modern Governance: New Government-Society Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1993; ISBN 0803988915. [Google Scholar]

- Kickert, W.J.M.; Koppenjan, J.F.M. Public Management and Network Management: An Overview; Netherlands Institute of Government: Enschede, The Netherlands, 1997.

- Richardson, J. Government, interest groups and policy change. Polit. Stud. 2000, 48, 1006–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agranoff, R.; McGuire, M. Big questions in public network management research. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2001, 11, 295–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanna, J.; Weller, P. The irrepressible Rod Rhodes: Contesting traditions and blurring genres. Public Adm. 2011, 89, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidle, K.; Normann, R.H. Who Can Govern? Comparing Network Governance Leadership in Two Norwegian City Regions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2013, 21, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baland, J.-M.; Platteau, J.-P. Halting Degradation of Natural Resources: Is There a Role for Rural Communities? Food & Agriculture Org.: Roma, Italy, 1996; ISBN 9251037280. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperial, M.T.; Ospina, S.; Johnston, E.; O’Leary, R.; Thomsen, J.; Williams, P.; Johnson, S. Understanding leadership in a world of shared problems: Advancing network governance in large landscape conservation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, D.; Rhodes, R.A.W. Policy Networks in British Government; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1992; ISBN 0198278527. [Google Scholar]

- Kenis, P.; Schneider, V. Policy networks and policy analysis: Scrutinizing a new analytical toolbox. In Policy Networks: Empirical Evidence and Theoretical Considerations; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 1991; pp. 25–59. ISBN 3593344718. [Google Scholar]

- Jessop, B. The Future of the Capitalist State; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2002; ISBN 0745622720.

- Olson, M.J. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, S. Advances in Social Network Analysis: Research in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; ISBN 0803943032. [Google Scholar]

- March, J.G.; Olsen, J.P. Democratic Governance; Free Press: Florence, MA, USA, 1995; ISBN 0028740548. [Google Scholar]

- Agranoff, R.; McGuire, M. Managing in Network Settings. Rev. Policy Res. 1999, 16, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, E.-H.; Teisman, G.R. Strategies and games in networks. Manag. Complex Netw. Strateg. Public Sect. 1997, 98, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Teisman, G.R. Models for research into decision-makingprocesses: On phases, streams and decision-making rounds. Public Adm. 2000, 78, 937–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J.F.M.; Klijn, E.-H. Managing Uncertainties in Networks: A Network Approach to Problem Solving and Decision Making; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; Volume 40. [Google Scholar]

- Scharpf, F.W. Interorganizational policy studies: Issues, concepts and perspectives. In Interorganizational Policy Making: Limits to Coordination and Central Control; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1978; pp. 345–370. ISBN 0803998805. [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg, E.; Crozier, M. Actors and Systems: The Politics of Collective Action; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1980; ISBN 0226121836. [Google Scholar]

- Zafonte, M.; Sabatier, P. Shared beliefs and imposed interdependencies as determinants of ally networks in overlapping subsystems. J. Theor. Polit. 1998, 10, 473–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H. The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2000; ISBN 0273650378. [Google Scholar]

- Kickert, W.J.M.; Klijn, E.-H.; Koppenjan, J.F.M. Managing Complex Networks: Strategies for the Public Sector; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; ISBN 144623195X. [Google Scholar]

- Susskind, L.; Cruikshank, J. Breaking the impasse: Consensual approaches to resolving public disputes. In Breaking the Impasse: Consensual Approaches to Resolving Public Disputes; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S.; Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; ISBN 0674312260. [Google Scholar]

- Bevir, M.; Richards, D. Decentring policy networks: A theoretical agenda. Public Adm. 2009, 87, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevir, M.; Rhodes, R. Interpreting British Governance; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, P.; Daugbjerg, C. Explaining governance outcomes: Epistemology, network governance and policy network analysis. Polit. Stud. Rev. 2012, 10, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevir, M.; Rhodes, R.A.W. The Life, Death, and Resurrection of British Governance. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2006, 65, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevir, M.; Rhodes, R.A.W. The State as Cultural Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; ISBN 0199580758. [Google Scholar]

- Bevir, M. Public Administration as Storytelling. Public Adm. 2011, 89, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huby, G.; Harries, J.; Grant, S. Contributions of ethnography to the study of public services management: Past and present realities. Public Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 1506336159. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, A.; Checkel, J.T. Process Tracing: From Philosophical Roots to Best Practices; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Geddes, B. Paradigms and sand castles: Theory building and research design in comparative politics; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- XNVC. Report on Xiaonan Village (Written in Chinese); Xiaonan Village Committee: Dalian, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- XNRC. Xiaonan Rural Chronicles (Written in Chinese); Liaoning National Publishing House: Dalian, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, Y.; Chen, B. Is competitive contracting really competitive? Exploring government–nonprofit collaboration in China. Int. Public Manag. J. 2012, 15, 405–428. [Google Scholar]

- Ngok, K.; Zhu, G. Marketization, globalization and administrative reform in China: A zigzag road to a promising future. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2007, 73, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.; Hassard, J.; Sheehan, J. Privatization, Chinese-style: Economic reform and the state-owned enterprises. Public Adm. 2002, 80, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Roland, G. Federalism and the soft budget constraint. Am. Econ. Rev. 1998, 88, 1143–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Qian, Y.; Weingast, B.R. Regional decentralization and fiscal incentives: Federalism, Chinese style. J. Public Econ. 2005, 89, 1719–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L. Are elections in autocracies a curse for incumbents? Evidence from Chinese villages. Public Choice 2014, 158, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q. The effect of population density, road network density, and congestion on household gasoline consumption in U.S. urban areas. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Bernstein, T.P. The impact of elections on the village structure of power: The relations between the village committees and the party branches. J. Contemp. China 2004, 13, 257–275. [Google Scholar]

- Visvizi, A.; Miltiadis, D.L. It’s not a fad: Smart cities and smart villages research in European and global contexts. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvizi, A.; Miltiadis, D.L. Rescaling and refocusing smart cities research: From mega cities to smart villages. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2018, 9, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Activating | Framing | Mobilizing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Examples in practices | Empowerment, tapping skills, etc. | Framing the interaction process, introducing new ideas, etc. | Emphasizing the impact of entrepreneurship, beliefs, group traditions, etc. |

| Theories | Resource interdependency theory | Network theory | Decentered theory of networks |

| Types of leadership | The local government in the primary leading position takes fully control of the governance process | The local government focuses on designing rules and institutions, and rural-village committees take charge of implementation | Rural-village committees mainly lead the governance, and the local government acts as a supporter and sponsor. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Yang, W. Leadership and Governance Tools for Village Sustainable Development in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205553

Liu Y, Yang W. Leadership and Governance Tools for Village Sustainable Development in China. Sustainability. 2019; 11(20):5553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205553

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yi, and Wei Yang. 2019. "Leadership and Governance Tools for Village Sustainable Development in China" Sustainability 11, no. 20: 5553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205553

APA StyleLiu, Y., & Yang, W. (2019). Leadership and Governance Tools for Village Sustainable Development in China. Sustainability, 11(20), 5553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205553