For the past several decades, the global community of scholars and policymakers has reached broad consensus on the profoundly damaging nature of corruption and the need to combat it. Key studies have demonstrated corruption’s negative impact on development [

19], including through the squandering of resources, the erosion of democratic legitimacy, and as an “additional tax” [

20] on new and current businesses. Instruments like Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) are now widely cited and used to evaluate a particular environment’s economic and political features. Legally, corruption is punished throughout the free world, both domestically and internationally. For instance, in 2018 alone, the US imposed over

$2 billion in penalties related to breaches of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), whereby companies are forbidden to bribe foreign officials [

21]. The vast majority of such efforts, however, only focus on government-related corruption, also referred to as political corruption or public-to-government corruption, i.e., “behavior [that] deviates from the formal duties of a public role (elective or appointive) because of private-regarding wealth or status gains” [

22].

2.1. B2B Corruption

Many scholars consider that businesses should behave in accordance with the carefully thought-out rules of moral philosophy [

23], in line with the objectives and values of our society [

5,

24]. Failure to meet these expectations of ethical behavior can harm a firm’s reputation, with potentially catastrophic results to shareholder value [

25]. If a company wishes to be perceived as a reliable partner in business, it has to act ethically and responsibly [

26]. This perspective would require businesses to fight actively against corruption if it goes against societal objectives and values, presumably even at the expense of business profitability, at least in the short term. Over the long run, adhering to corrupt practices can hurt a company’s competitiveness and viability.

There has been little scholarly and policy interest for the issue of private-to-private or business-to-business (B2B) corruption, despite the fact that agreed definitions and instruments cover both private and public forms of corruption. The literature provides a wide range of definitions, from abuse of power to misuse of resources for private benefit. Transparency International, for instance, defines corruption as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain” [

27]. The OECD explicitly notes that corruption is “the abuse of a public or private office for personal gain” [

28]. In their 2004 article, Anand, Ashforth, and Joshi further note that corruption as the misuse of an organizational position “refers to departures from agreed societal norms” [

29]. For the purposes of this article, private or B2B corruption can be defined as the abuse of authority in transactions between private parties to extract undue benefits.

Beyond definitions per se, it is important to explore the reasons behind the reduced focus by scholars and policymakers on private corruption. Some argue that transactions between private parties are typically private matters, and any potential conflicts are typically resolved internally [

7] (p. 253). Also, as profit-maximizing entities, private companies should be capable of eliminating any transaction that hurts their bottom line. Based on classical liberalism, the “invisible hand” should inevitably guide business organizations in the right direction [

30]. Others note that private actors are simply subject to less scrutiny, as they do not deal with taxpayer money, so company employees typically have “a bigger scope for arbitrary decisions,” particularly in procurement [

31]. These arguments, while valid, do not justify failing to investigate and sanction private corruption. Indeed, key stakeholders (shareholders, management, etc.) may have the desire but not the knowledge or capacity to perceive and combat corruption acts unfolding in their companies, as shown below.

In arguably the first article on the topic, Argandoña describes the full list of forms of B2B corruption: “bribery (when it is the person who pays who takes the initiative); extortion or solicitation (when it is the person who receives the payment who takes the initiative, whether explicitly or otherwise); dubious commissions, gifts, and favors; facilitation payments (to speed up completion of an order, delivery of goods or payment of an invoice, for example); nepotism and favoritism (in the hiring and promotion of personnel, for example); illegitimate use or trading of information (trade or industrial secrets, for example); use of undue influence to change a valuation or recommendation; and an endless array of other possibilities born of human ingenuity over the centuries” [

7] (pp. 255–256). The same author [

7] argues that B2B corruption is punishable by law primarily based on: breaches of fiduciary trust; undermining of free market competition; fraud; insider trading, etc. B2B corruption negatively impacts market-based mechanisms, creating inefficiencies, eroding trust among businesses, harming employees’ loyalty toward their companies and respective shareholders, and contributing to a general societal culture of corruption [

7]. There is therefore a prevailing view that B2B corruption is indeed harmful, both for individual businesses and society as a whole.

Current international laws confirm this perspective. Recognizing the risks and costs of the phenomenon, as early as the 1990s the international community adopted important acts designed to combat corruption and B2B corruption specifically. These include: the Inter-American Convention against Corruption (1996) [

32], the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions (1997) [

33], the EU’s Joint Action on Private Corruption [

34], the Council of Europe’s Criminal Law Convention on Corruption (1999) [

35], and the EU’s Council Framework Decision 2003/568/JHA [

36] on combating corruption in the private sector (2003). Often cited is the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), also adopted in 2003, which includes specific provisions on B2B corruption under Article 21, covering the demand and supply sides (i.e., both requests and offerings of “undue advantage” to act or refrain from acting, in breach of duties) [

37]. These international initiatives are vital as a signal that B2B corruption exists and requires attention, though international conventions like the UNCAC are not directly enforceable at the level of each signatory.

As the specialized literature shows, combating B2B corruption requires much more than legal instruments, and the most effective measures appear to be bottom-up, i.e., starting at the level of each private entity. Anand, Ashford, and Joshi offer an in-depth account of tactics to rationalize and socialize corruption, including denial of responsibility, denial of injury, cooptation, incrementalism, etc. [

29]. All these lead to corrupted perceptions of behavior, whereby perpetrators appear to act morally and those opposing them are gradually converted to such practices or excluded from the organization. Such behavior can easily translate to an entire sector, business environment, and society. It is therefore vital to find out how business people understand the phenomenon and how they explain it.

2.2. Determinants of Private Corruption

The literature on B2B corruption shows that it is often challenging to perceive, recognize, measure, and fight against it. Surveys may underestimate the scale of the phenomenon, as they can miss some of the determinants favoring corruption [

38,

39,

40,

41]. For one, due to the illegal and covert nature of corruption, research subjects may not want to share their experiences for fear of potential repercussions in terms of legal penalties, reputational costs, etc. Moreover, quantitative surveys have to be based on perceptions, which are inherently subjective. As noted by Kaufmann, Kraay, and Mastruzzi, “perceptions of corruption based on individuals’ actual experiences are sometimes the best, and the only information we have” [

41]. In terms of business attitudes and investors’ trust, perceptions may matter more than reality; in other words, if a country’s private sector is perceived as very corrupt, there will be dire economic consequences in distorted competition and limited investment, regardless of whether corruption is real or not.

A 2008 exploratory study by C. Gopinath demonstrated the complexity of private corruption assessment (recognizing and justifying B2B corruption) and identified determinants of corruption at the private level (cultural reasons, mentality, and lack of moral principles). The author surveyed students from a business school in North America to explore their perceptions and attitudes vis-à-vis private corruption [

42], and sought answers to three distinct research questions: (i) Are individuals able to recognize ethical issues in private transactions? (ii) What arguments do they use to justify unethical behavior? (iii) Would individuals act differently when faced with public vs. private corruption?

Gopinath [

42] administered a brief questionnaire presenting a hypothetical scenario faced by the manager of a company visiting a partner organization in India. A clerk in the Indian company notes that he can speed up import papers if he is paid overtime by the visiting manager. There is also an option to pay something to the customs officials. The manager has to decide whether to accept or refuse the requested payments. Gopinath found that indeed individuals had difficulty recognizing bribery in the case of private corruption. The qualitative assessment of the sample reasons provided for their decisions shows that respondents justify making the payment for business reasons, noting that it is a harmless bribe, that it is common practice in developing countries, or that facilitation payments are not illegal. There was no standardized assessment of the situation. Only 20% referenced moral principles in making their decision, while 11% of respondents cited cultural reasons, some noting that India is known for the wide prevalence of such practices [

42].

In the case of B2B corruption, the added complication in explaining it is that some subjects may not even see it as such. Particularly because there is no public money involved, perpetrators themselves—along with those around them, e.g., colleagues, business partners, etc.—tend to justify corrupt actions by claiming they are actually furthering their respective companies’ interests in an environment where others may be resorting to the same tactics [

29]. The general context, cultural norms, as well as the complexity of bureaucracy are among the determinants that explain private corruption. Firms might be engaging in corruption among themselves to strategically counter perceived bureaucratic power [

43] (p. 759). The degree of corruption may be determined by the level of economic freedom, socio-political stability, tradition of law abidance, and national cultures [

38]. Studies mention economic variables (government consumption, level of development), governments effectiveness, and cultural factors as determinants that significantly affect corruption [

44,

45,

46].

Beyond such inherent challenges, there are still only a few quantitative surveys focused on B2B corruption, as much of the research continues to focus on corruption in the public sector, including the two key instruments from Transparency International (TI): the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) [

47] and the Global Corruption Barometer (people’s experiences with bribing officials for basic services) [

48]. Some surveys like TI’s 2011 “Putting Corruption Out of Business” [

49], the Flash Eurobarometer 374 “Business Attitudes towards Corruption in the EU” [

50], the World Bank’s BEEPS survey [

51], and the “International Business Attitudes toward Corruption” study by Control Risks [

52] are useful in understanding the prevalence of corruption in various countries’ private sectors, as well as available tools for businesses seeking to combat this phenomenon. However, these studies fail at distinguishing between public and private corruption. Most questions, in fact, refer clearly to transactions in business-to-government (B2G) or equivalent relations—i.e., winning public tenders, obtaining construction permits, financing political parties, etc. [

50].

Notably, TI’s Bribe Payers Index (BPI) does include for 2011, the most recent year available, specific questions on B2B corruption [

53]. The BPI ranks 28 countries based on their respective business executives’ answers around paying bribes when operating abroad, on a scale of 0 (always bribe) to 10 (never bribe). For the first time in 2011, the BPI also asked over 3000 executives about how often firms in each sector “pay or receive bribes from other private firms” [

53] (p. 18). The results show that B2B corruption is more prevalent in public works and construction, utilities, real estate, and oil and gas, and less prevalent in agriculture, light manufacturing, IT, and banking and finance. Interestingly, there are no significant differences perceived between prevalence rates for petty/grand B2G corruption and B2B corruption: “this provides evidence that corruption is not just a phenomenon that involves public servants abusing their positions, but it is also a practice within the business community” [

53] (p. 19). As TI further notes, while B2B bribery remains often overlooked, its consequences are very serious, including distorting markets, increasing costs to firms and consumers, and penalizing those corporate actors who either cannot or will not engage in corrupt acts vis-à-vis other firms.

For its part, the European Union has started to devote increasing attention to B2B corruption, including through funding of research studies, which further strengthens the view that this is a deeply harmful phenomenon requiring clear focus and solutions. One example is the 2013 report on Croatia, which measures the prevalence of B2B bribery—in Croatia vs. the Western Balkans—as “the number of businesses who gave money, a gift or counter favor, in addition to any normal transaction fee, on at least one occasion in the 12 months prior to the survey to any person who works, in any capacity, for a private sector business entity, including through an intermediary” [

54] (p. 37). The research also compared business sectors in terms of private corruption prevalence, forms of payment (most often, exchange with another favor, while cash or other benefits are least frequent), modality (in 60% of the cases a bribe request is made), and timing (most at the same time as the service delivery). Reporting rates are extremely low: in less than 1% of the cases, the police are informed about B2B bribes [

54] (p. 48).

Another EU-funded study is the Private Corruption Barometer [

6], also known as Project PCB, which was launched to fill the gap in available data on the perception and experience of B2B corruption, as well as to agree on a set of common indicators to measure this phenomenon across the EU. Project PCB covered four Member States, including Bulgaria, Italy, Spain, and Germany, with national samples including both small/medium/large companies (in terms of number of employees) and covering different sectors (industry, trade, services, hotels/restaurants, and construction). The questionnaire covered multiple areas: general B2B corruption perceptions; experiences (knowing someone who had been offered gifts/money/other benefits); and anticorruption measures’ effectiveness, from termination of contracts to internal control systems. Overall, the study shows similar attitudes vis-à-vis B2B corruption in Germany, Italy, and Spain, with clear differences compared to Bulgaria, where the phenomenon appears to be both more prevalent and more accepted among survey respondents.

Arguably the most extensive study of B2B corruption funded by the EU is the 2016 PrivaCor, which compares the phenomenon in Estonia and Denmark, having interviewed 500 managers in each country [

55]. The authors justify the study by noting that “most EU countries lack information about the extent and forms of corruption in the private sector” [

48] (p. 8). To fill this void, the research looks at: forms and frequency of B2B corruption; excuses/justifications given for corruption acts by private actors; awareness of consequences; and recommended measures to combat corruption through improved business practices.

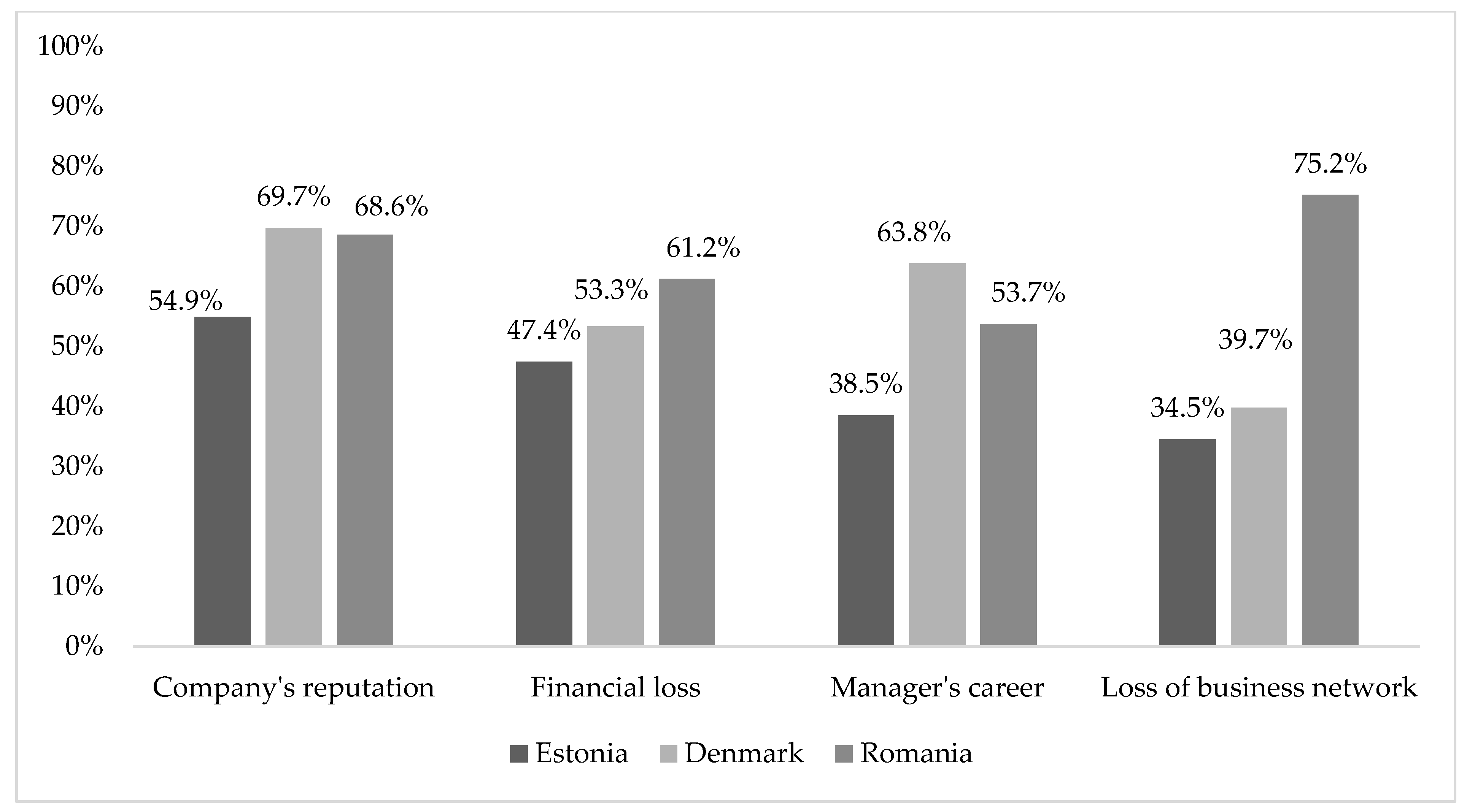

Multiple findings of the PrivaCor study help shed light on B2B corruption. For one, the phenomenon is present and significant in both states: 57% of Estonians and 51% of Danes had encountered at least one type of corruption within their sector, with kickbacks and conflicts of interest as the most prevalent. The main excuses for corruption are similar in both countries: pressure from upper management, followed by “everyone else does it.” Smaller companies and local-owned firms are more likely to invoke excuses compared to larger or foreign-owned businesses. The main consequences feared by respondents are damages to the company’s reputation and financial losses, while “male managers are more concerned about the negative effects on their own careers than their female colleagues” [

55] (p. 5).

In terms of solutions for combating corruption, studies underline the importance of both internal and external solutions [

7,

43,

46,

55,

56]. PrivaCor shows the willingness of respondents in both countries to act. Only 3% of managers in Estonia and 10% in Denmark would not blow the whistle on a corruption case, and the vast majority would handle the issue internally. Over 90% of subjects in both countries note that managers’ personal example can be effective to fight corruption. Another important conclusion is that guidelines and public awareness of B2B corruption continue to lack in both countries. There are also some differences: “only 27% of Estonian managers find law enforcement (police or prosecutors) effective, compared to 72% of the Danish managers” [

55] (p. 5). Danish managers also value trainings and ethical standards more than their Estonian counterparts. Other recommendations to fight against B2B corruption are: develop a toolkit for identifying high-risk areas within each company; hire the right people, including by accessing proper background checks; and clarify procedures for reporting (e.g., hotlines, independent trustees, etc.).

Along the same lines, in his seminal 2003 study of B2B corruption, Argandoña recommends clear and transparent standards, with specific examples of potentially problematic situations, specialized trainings, as well as drastic sanctions, as needed [

7]. Anand, Ashford, and Joshi make similar suggestions to combat the phenomenon: adoption of codes of ethics, actions to promote awareness, design and enforcement of whistleblowing protections, involvement of external change agents [

29]. Goel, Budak, and Rajh show that, among different anti-corruption policies (including internal and external measures), a firm’s internal code of ethics proved to be an effective deterrent [

43]. Rose-Ackerman also emphasizes the importance of company-led measures, including personnel policies for hiring people with strong morals, along with credible whistleblowing mechanisms [

56].

It is clear from the review above that more empirical research, investigating the determinants of B2B corruption in different contexts, as well as exploring business leaders’ understanding of the phenomenon help develop appropriate solutions to fight against this social disease.

2.3. Corruption in the Romanian Context

Societies with a long tradition in rule of man instead of the rule of law register high levels of corruption [

57]. During the communist period, Romania (as other communist countries) followed the rule of man, as the law served primarily the interests of the nomenklatura [

58]. The transition period did not create the conditions for strong rule of law; if fact, it brought even more confusion regarding the role of institutions, the legitimization of business, and people’s trust in market economy mechanisms. The corruption cases related to the privatization process generated high public skepticism regarding the fortunes amassed by some, in a short period of time, particularly former activists, their friends or relatives, or former directors of state-owned companies [

59] (p. 667).

Indeed, for decades, Romania has been perceived as one of the most corrupt countries in Europe, a story confirmed by all major perception-based surveys and indicators. In 2018, Romania’s CPI score was 47, placing the country as the fourth most corrupt in the EU, closely behind Hungary, Greece, and Bulgaria [

60]. Other indicators support this view. TI’s Global Corruption Barometer in 2016 places Romania first in the EU in terms of the percentage of households that have paid a bribe—29%, with Lithuania a distant second at 25% [

61]. The Bertelsmann Foundation’s Sustainable Governance Indicators for 2018, particularly the one measuring democratic quality and rule of law, including corruption prevention, shows that Romania is third to last in the EU, ahead of only Poland and Hungary, respectively [

62]. Freedom House’s Nations in Transit report paints a similar story, with corruption scores of between 4 and 3.75 between 2009 and 2018; in 2018, only Bulgaria, Croatia, and Hungary fared worse than Romania in this aspect [

63]. The World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) dataset on control of corruption also shows Romania third to last in the entire EU, followed only by Greece and Bulgaria [

64].

More data are available from EU-led research. The October 2017 Flash Eurobarometer shows that 85% of business people consider corruption to be a problem in Romania, versus 37% as the average across all 28 member states [

65]. 96% of businesses surveyed consider the issue to be widespread in Romania, particularly bribes, kickbacks, and nepotism in public institutions. At the general public level, corruption is seen as widespread by 80% of interviewed subjects; 46% of all subjects consider that corruption has increased over the past three years, while 37% believe it has stayed the same. Only 10% believe it has decreased. 68% of all respondents believe that corruption affects their daily life, compared to only 25% as the EU28 average. Interestingly, 26% of surveyed Romanians believe that corruption is widespread in private companies versus 40% as the EU28 average; along with perceptions of corruption in banks and financial institutions (26% in Romania vs. 33% EU28 average), this is the only sector where Romania scores better than the EU28 average, which suggests that Romanians may see private companies as a less critical source of corruption compared to the public sector. At the same time, when probed further, 80% of surveyed Romanians “totally agree” or “tend to agree” with the statement that “corruption is part of the business culture in Romania” [

66].

Importantly, the data mentioned above do not refer to B2B corruption specifically. Certainly, one can speculate that business people who consider corruption to be widespread in Romania may have encountered it in transactions between companies as well. The 26% of surveyed Romanians who believe corruption is widespread in private companies may refer to B2B transactions, but it is more likely that they actually reference business-to-government corruption, which is a lot more visible in the media, particularly when it comes to real estate and infrastructure works, as well as the health sector. This is in no way unique to Romania. In his 2003 study, Argandoña makes precisely this point: “the cases of corruption reported by the media tend to almost always involve a private party that pays or promises to pay money to a public party” [

7] (p. 253).

Unfortunately, as of June 2019, there are no surveys or other types of studies focused on Romania’s B2B corruption specifically. The current research is indeed a first of its kind, and, as explained below, it focuses on C-level managers, who are likely to know more about the prevalence and mechanisms of B2B corruption. At the level of the general population, until recently, there had been no media scandals or major B2B corruption cases reported, so it was reasonable to presume that the phenomenon remained largely unknown or ignored by most Romanian citizens. This changed in August 2019, when public opinion was shocked to hear that the head of one of the largest corporations in the country was under investigation for B2B corruption charges for kickbacks requested in previous years, totaling over 800.000 euros. This high-profile case has not only helped inform the Romanian business community and broader society regarding the risks and costs of B2B corruption, but it has also brought new attention to the topic, with more and louder voices calling for common standards and clear solutions to combat this phenomenon. It is clear that more empirical research, especially on a case like Romania, widely perceived as a corrupt country and understudied with respect to B2B corruption, will help not only to understand this phenomenon, but also to provide solutions to fight against it. As an exploratory research, the current study starts from the findings of the existing literature and provides—albeit at a preliminary level—answers to three research questions.

Q1. What determinants favor B2B corruption in Romania?

Q2. Is there a standardized understanding among Romanian business leaders on what constitutes B2B corruption?

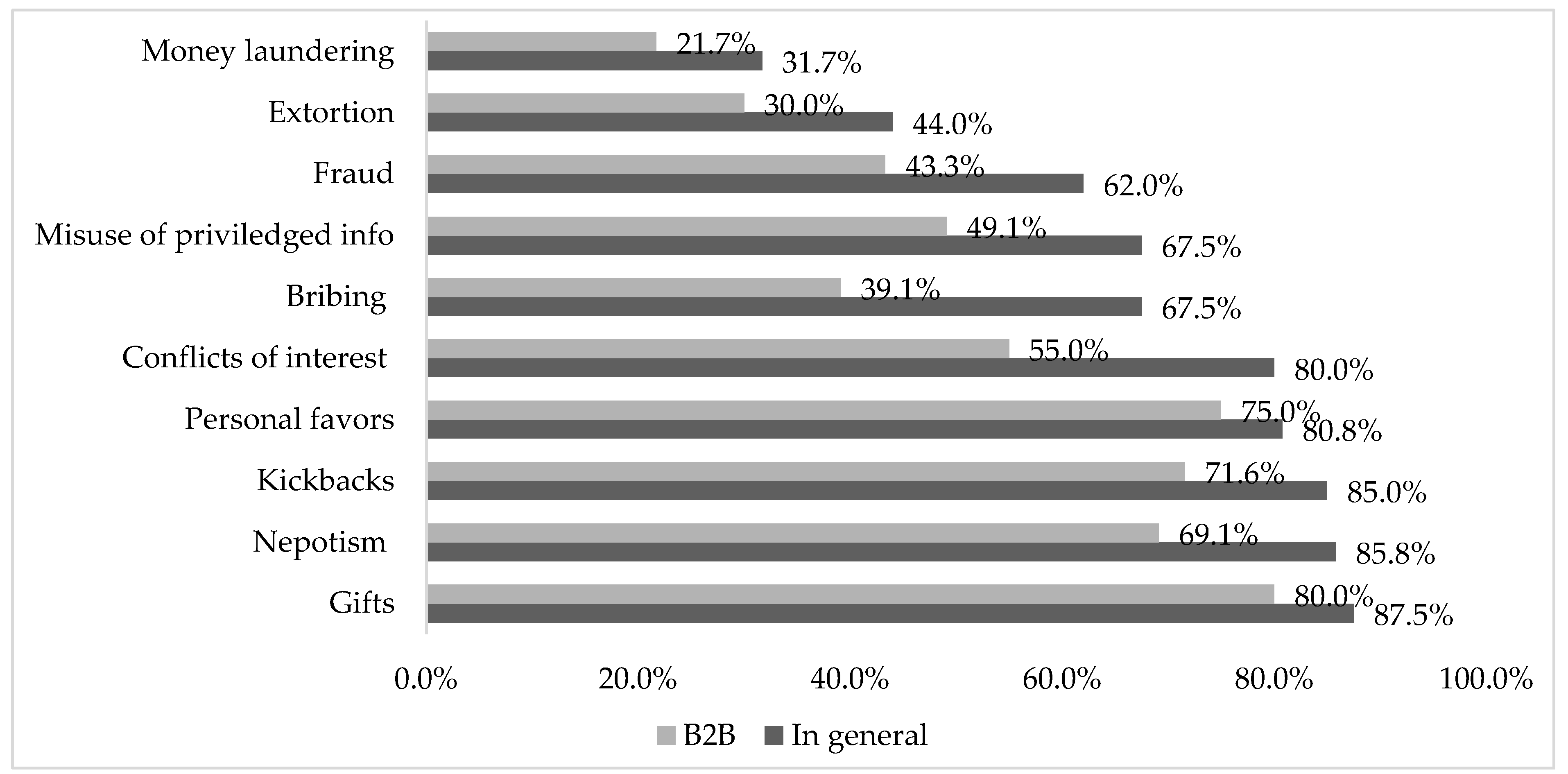

Q2a. What forms does B2B corruption take?

Q2b. Does the probability to face B2B corruption forms increase with professional experience (i.e., number of years since entered the labor force)?

Q3. Do Romanian business leaders want to play a role in combating B2B corruption?

Q3a. What kind of solutions do Romanian Business leaders prefer when it comes to combating B2B corruption?