Abstract

The need for understanding the context of the case company during Design for Sustainability (DfS) implementation has been a long identified need among the researchers in the field. Yet, studies on company context have primarily focused on studying, enlisting, and prescribing standardized solutions for companies or clustering companies based on similarities. Such approaches have not been able to overcome the organizational “soft side” challenges that have been long addressed in DfS literature. This explorative paper takes insights from 20 case interviews conducted in Norwegian and Danish manufacturing companies and with sustainability experts and uses the concept of persona from design studies to explore the potential of defining “company personas” to better define the context of the company. The interview analysis produced 14 dimensions, including both hitherto identified factual needs of companies and soft-side elements required to create a company persona, thereby informing practitioners and researchers to take a DfS implementation approach tailored to the company context.

1. Introduction

The need for sustainability considerations in product design and development processes has been gaining greater acceptance in industries. One of the initial responses to including environmental concerns in product development was termed as eco-design or design for environment [1], which mainly had a product focus. In the past 25 years, the field went through several transitions [2] and gradually expanded in focus to incorporate sustainability, service, and business perspectives, and is now commonly referred to as Design for Sustainability (DfS). This transition also paved way for academic discussion to widen the scope of DfS to include the socio-spatial context of the product design in addition to environmental concerns [3], including service perspectives (PSS) [4] and business [5] perspectives. Even though the concept of DfS has been a focus subject in both academia and industry, academic reviews suggest that DfS implementation has faced a number of barriers and challenges in actual implementation stages [6]. Addressing these challenges, a part of academic discussions focused upon the contextual factors existing within and beyond the company boundaries that could have a possible impact on successful DfS implementation [7]. Solutions put forward by academia to overcome these challenges have been mostly in the form of standardized DfS tools, checklists, and matrices [8]. However, most of these solutions have failed to create desired results or have not been widely used in industry [9]. This is mainly because most challenges and enablers for DfS implementation vary depending on the context of the company, and standardized solutions are less likely to be effective in such situations [7,10].

Some studies in the DfS literature have focused on highlighting the contextual differences that exist within companies involved in sustainability implementation [11,12,13]. Domingo et al. [14] presented one such case study based on two companies where the context of the companies was characterized using a three stage process, namely mapping the company’s business context, identifying its key development areas, and developing an eco-design introduction plan. The characteristics identified included the management structure, product development process in the company, environmental knowledge in the business, strategic focus of the company, business drivers for DfS and its feasibility, and the role of the company in the value chain. Elsewhere, researchers clustered companies into sustainability leaders, environmentalists, and traditionalists based on their approach to sustainable development [12]. With an exception of Domingo et al. [14], these mentioned studies primarily focused on clustering the companies based on commonalities existing in its company context and sustainability preparedness. In a later study, to assess companies based on their sustainability readiness, Pigosso et al. [8] proposed a sustainability maturity model for companies that looked into the level of formalization for eco-design implementation, the capability level existing within the company, and the steps to progress to higher maturity among others. While the maturity model prescribed an in-depth path of progression for companies in the sustainability journey based on its capabilities and eco-design evolution, the prescriptions were often unidirectional in nature, irrespective of the companies’ human and social factors. Even though such an approach provides general recommendations on how companies can progress, the authors of this paper believe that uncovering niche characteristics of the company will complement efforts from researchers in addressing DfS implementation challenges. Thus, this paper aims at placing itself at this conjunction between importance of company context and hitherto the lesser-addressed “soft-side” (human and social factors) of DfS implementation.

Such a balanced approach can be seen in design literature, where designers aim to provide design solutions that better fit to the needs of their product users by identifying the distinguishable characteristics of the users and collectively addressing users with similar characteristics as “personas”. User personas used in design processes provide a close description of the targeted user, his/her aspirations, and what he or she aims to achieve from the product or service being designed [15,16]. Chang et al. [16] observed that user personas can be made for just one person in mind, as proposed by Cooper [15], or it could be an aggregation of user characteristics of similar stakeholders that present a “mash up” of people [17]. Drawing from this area of design research and combining it with the aforementioned DfS implementation scenario, we assume that companies, as product users, possess certain characteristics that distinguish them from others; and on the other hand, there are companies that are comparable to each other in terms of their operational internal and external contexts. If we assume this, it is interesting to attempt to identify which characteristics may be relevant to distinguish from a DfS perspective, which dimensions they will entail, and whether—and in what manner—those dimensions can be identified in a comprehensive manner. This is the starting point of this explorative paper, where the aim is to gain insight into the feasibility of constructing “company personas” from a sustainability perspective with the possibility of eventually using these personas to facilitate choices related to which DfS tools and methods may be most suitable for that company, and how they can be implemented best. For this purpose, a company persona is tentatively defined as an archetypal set of characteristics of the company in functional, organizational, business strength, and value chain dimensions, which can be used to distinguish the company it is projected on from other types of companies or to enable it to be clustered with other similar companies. Drawing parallels from academic and design studies on user-based (or end-user) design strategies—where the user occupies the center stage in the design process—this paper proposes the idea of placing the company in the center focus of academic research on mitigating DfS implementation challenges. As design practitioners often resort to the “user persona” as a design method to facilitate user centered design approaches, this paper investigates the “company persona” in a similar way.

In order to better inform this process, the paper firstly presents the theoretical background of personas from design literature and explores how this can contribute to such a discussion. Secondly, the paper discusses the existing literature on DfS implementation that has tried to identify the different contextual aspects of companies, and how they may influence successful DfS implementation in companies. Finally, the literature findings are corroborated with results from 20 semi-structured interviews carried out with seven different companies that have a DfS focus in their product development and with four sustainability experts who have worked with DfS implementation in companies. This paper aims to further discuss the role of contextual factors of organizations in DfS implementation. The authors approach this case by presenting academic view points and insights from interviews with industrial actors on how identifying and defining the “persona” of an organization may improve development of tools, methods, and approaches for integrating sustainability considerations in design processes. The paper thereby also aims to explore the potential of future prescriptive research that can be placed in between generalist and customized approaches. Theoretical research is often accused of lacking practical application potential, and general guidelines for DfS implementation may lack relevance for individual companies due to the different contexts they operate in. On the other hand, customized approaches (such as those based on individual case studies) may lack the potential of generalization and applicability beyond a single context. It is our hypothesis that zooming in on a company persona level when developing a company-specific approach avoids disadvantages that exist on either side of this spectrum. The targeted audience for the use of such “company personas” is mainly twofold; firstly, there are the sustainability/eco-“champions” in companies or proponents of sustainability initiatives who can use it as a self-reflective tool in the implementation process, and secondly, there are the scholars and sustainability consultants working towards improving DfS adaptation and implementation in companies.

In summary, this paper explores the potential of constructing “company personas” in a similar vein as “user personas” based on dimensions that characterize the company and assesses thereby their potential contribution to developing tailored DfS implementation approaches.

2. Theoretical Framing

The following section presents findings from a traditional literature review [18], carried out to explore the importance of context of the company in the DfS implementation scenario, and insights from user persona literature to guide the discussion presented in this paper. The literature search was primarily carried out using Google Scholar and the Scopus database. As the interest of this paper lies in exploring user personas from a practitioner’s perspective, additional inputs from case studies available on online webpages and blogs by designers were also included.

2.1. Persona Origin, Definition, and Dimensions

The origin of the persona as a research topic is widely found in user centered design literature where the user is placed in the center of the design process. Alan Cooper introduced persona as a method for designers in late 1990s in his seminal work titled, “The inmates are running the asylum”. In the book, Cooper observes that designers often have unclear or vague ideas of the end user of the product and are most often driven by user scenarios similar to the designer himself/herself. To overcome this shortcoming, Cooper suggests the “goal-directed-design”, where multiple user centered research methods such as interviews, ethnographies, etc. are combined with market research, user requirements, and goals in order to better define the user and his/her needs [15]. For this paper, personas are defined as user classes fleshed out into “user archetypes”, which gives the required precision to the design activity of the designer.

2.1.1. Benefits of Using Personas

The popular support for personas comes from its advantage over scenarios due to close proximity to the reality of the design goal and the engaging nature of personas [19]. Personas help design teams in thinking about users during the design process, make efficient design decisions without inappropriate generalization, and facilitate communicating about users to various stakeholders [20,21].

Miaskiewicz and Kozar [22] used the Delphi technique to rank the benefits of using a persona identified from literature: first is audience focus, where the end user of the product is the main focus; second is product requirements prioritization, which regards product requirements and ensures that the right problem is being solved; third is audience prioritization, which brings about a focus on the most important audience; the last benefit is challenging assumptions that are often incorrect about the users/customers. These are some of the top benefits identified in that paper. Further, literature also observed that the creation of personas made communications in design environments easier and more explicit. The efficacy of driving the debate and arriving at design decisions made the technique popular among designers [23]. Political and social characteristics of users remained mostly unaddressed in earlier design cases; however, the use of personas helped in recognizing and challenging such characteristics [23,24,25]. Using personas helps to create an embodiment of the needs and goals of the users, thus providing additional specificity and avoiding the higher level of abstraction in the definition of the user [26].

A common application of the persona tool is observed in IT system implementations in companies, where we could identify a predominant number of examples that tend to define the persona characteristic of the user being targeted. Rönkkö et al. [25] identified certain characteristics for a case company where persona as a design technique was used but failed to overcome the design challenge. These characteristics included the demographics of the company, the field of work, their expertise in the field, years of experience, department structure, etc. The article, however, notes that the persona technique failed because it did not take into account the external environment of the company, e.g., the stakeholders outside the company. Mathews et al. [21] observed that, despite its limitation, the power of persona as a technique lies in bringing out “some irreconcilable differences between various design stakeholders”. The authors of this paper believe that while defining the company persona, which is explained in detail in the following sections, the definition should include characteristics both external and internal to the company for successful implementation of DfS.

2.1.2. Creation of Personas from Design Literature

Faily and Flechais [20] identified three main steps in creating a persona; firstly, summarizing the proposition by identifying the thematic propositions that the persona shall address. Secondly, enumerating and explaining the characteristics identified for the persona. Finally, creating detailed narratives of the persona characteristics and other supporting narratives.

Floyd et al. [27] identified the different kinds, attributes, and characteristics of personas based on existing literature and case studies. They categorized the persona technique into seven major kinds based on the detail of description, the intended purpose, and what kind of data are sourced to create a persona. The first, classic kind of persona identified by Floyd et al. [27] is the one proposed by Alan Cooper, which relies on in-depth ethnographic research and tries to create as many initial personas as possible [15]. Floyd et al. [27] further observed that in the “Cooperian” style of personas, the initial personas are developed to capture the basic understanding of user characteristics and are then merged through analysis to arrive at one primary persona for each user kind. The final personas are maintained throughout the rest of the design process and discarded at the end of the project. Floyd et al. [27] classified these “Cooperian” personas into two kinds, Cooperian Initial Personas (CI) and Cooperian Final Personas (CF).

The second type of persona is the kind used by Pruitt and Grudin, which is characterized by its massive data driven approach, both quantitative and qualitative. The personas developed this way are retained even after the project is completed to be used and adapted in future projects because of the data backed approach [19,27]. The third kind of persona identified by Floyd et al. [27] is Sinha personas, which are also data driven (primarily quantitative) but less comprehensive in comparison to the other kinds [28]. Floyd et al. [27] further explained three other types of persona, namely ad hoc personas and marketing personas. The ad hoc persona is derived from intuition and experience of the designer but is discarded after the design cycle is complete. The user archetypes are similar to personas except that they are more generic and cater to a larger audience than the designer’s extreme user personas. It is less precise when compared to a persona, thus also qualifies with more general information. Dantin [29] studied the user archetypes intended for two online platforms, outlining the general public targeted with the service and making it “elastic” [27], describing several people simultaneously.

Further, Cooper [15] noted that each human persona has a work environment, socio-economic dimension, and demographic dimension of culture, ethnicity, or race to it. Pruitt and Grudin [23] further elaborated on these by looking into a set of dimensions in the case example that included goals, fears, and aspirations of the user, market size and influence, knowledge, skills and abilities, communication, views and opinions, attitude towards the solution/product, etc. Extrapolating these observations from the different characteristics that encompass a user persona in the company context and perceiving companies, like humans, as “organisms” who strive for survival and recognition, it is reasonable to assume that companies also likely possess characteristics that distinguish them from others. In order to further guide this research on what these likely company characteristics could be in DfS context, Section 2.2 elaborates on research findings from earlier studies that looked into the contextual issues encountered during DfS implementation in companies.

2.2. Design for Sustainability Implementation and Relevance of Company Context

As stated in the introduction, academic research on DfS increasingly acknowledges the need to address the overall socio-organizational context of the company in addition to the technical details that DfS projects demand [30,31,32,33]. These include the change management perspective for eco-design implementation in companies [33], company characterization based on the business features for eco-design activity planning in companies [14], and managerial motivations behind sustainability activities [12], among others. Companies need to emphasize their communication structure, their need of cooperation between companies, the alignment of needs and expectations between proponents and executors, and the need for the establishment of market demand for DfS products in addition to focusing on the technicalities of the products [34]. Lack of integration of DfS and corporate strategy [8], difficulties in defining and planning the activities for DfS implementation, and challenges in prioritizing the eco-design practices in companies [35] also add to these barriers. Companies often need strategic visions and policies with an accompanying viable business case to prioritize and drive integration of DfS in its product development activities [12,30,36]. Research has also shown that senior management should ably support DfS initiatives by performing regular follow ups [37], making compulsory contributions in terms of guidance and resources [14], and providing flexible environments that promote innovation on sustainability topics [38].

Further, researchers who studied the external environment of a company and the role of stakeholders from a sustainability implementation perspective identified the need for stakeholder involvement and management of the stakeholder relationship, both internally and externally [39,40]. Engaging with external actors on sustainability topics can provide a great learning experience for companies [5] and increase the feasibility for such projects [37]. Internally, it is important for companies to align DfS initiatives with overall product lifecycle management to encourage participation from all departments [41] and thereby garner clarity in the DfS implementation process [42]. Dealing with seven “sustainability blunders” that companies usually commit in eco-design implementation, Doppelt [38] opined that ways of organizing sustainability strategy teams and ensuring alignment in the vision and activities of the teams are the first steps to creating a sustainable enterprise. Companies also act as communities with their own aspirations, ambitions, beliefs, and hardships in different contexts, thus warranting differential treatment [43]. The DfS activities they undertake need external stimulus for generating a consistent demand for sustainable products. This should be integrated in the actual project management process within the company in order for it to be successful [30,37]. Johansson [31] also mentioned the need for regular and recurring environmental assessment in all stages of the Product Development (PD) process. In addition, a number of other factors existing within and beyond the company boundaries—such as the position in the value chain, and its influence or capability to integrate, collaborate, or negotiate higher or lower in the hierarchy of the value chain—may also affect how DfS implementation can best be approached. Elsewhere, while studying the role of resistance against sustainability and internal communications in sustainable design implementation in companies, Verhulst and Boks [33] highlighted the need for different communication styles that inform, support, and involve the employees of the company. Parallel to the discussion on the “soft-side”, there has been significant research focus on DfS tools and methods, which have been primarily quantitative in nature but with a few exceptions of semi-quantitative or qualitative tools [44]. However, the uptake of these tools is marred by the need for specific knowledge to use and understand the results [31], the oversimplification of certain results [44], the overwhelming number of tools to choose from [8], and the lack of envisaged market opportunities for eco-design products [45]. Hence, it is evident that most often, the “off-the shelf” solutions such as Life Cycle Assessments (LCA), design matrices, design for X solutions, checklists, and tool-based prescriptions offered to DfS challenges are likely to be ineffective or at least insufficient without a customized implementation plan.

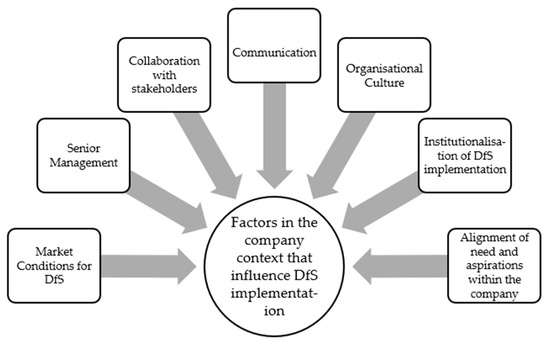

Thereby, these factors that exist within the company context and have an established influence on the DfS implementation scenario in companies, as summarized in Figure 1, warrant attention from the researchers working to improve a DfS implementation process. Personifying companies and approaching these contextual factors as defining characteristics of companies underlines the hypothesis presented in this paper that companies, when seen as customers for as users of a DfS implementation strategy, can be represented by personas. Relating this to characteristics stated in Section 2.1, there is a clear connection between how these different factors of company context can be employed under the persona methodology. The following sections present the insights from empirical data collected and data analyzed to further explore this understanding.

Figure 1.

An illustration of different factors in the company context that influence the Design for Sustainability (DfS) implementation process as identified from literature.

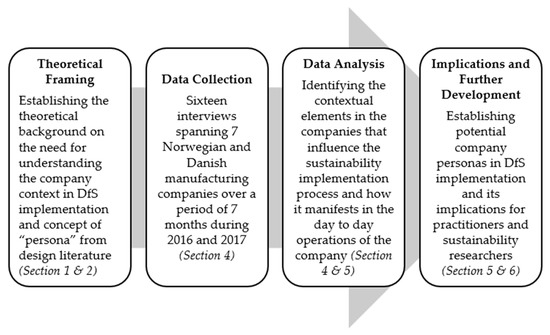

3. Research Method

The research methodology adopted in this paper is outlined in Figure 2. It was inspired by the case study approach presented by Yin [46] and Cassell and Symon [47], which began by framing the boundaries of the case, collecting the data, analyzing the data, and leaving the case study by relating the findings and their implications to the existing body of knowledge.

Figure 2.

Outline of the research methodology.

3.1. Case Interviews

The sixteen case interviews were carried out in seven Norwegian and Danish manufacturing companies that had a sustainability focus in their product development and clearly outlined sustainability goals in their official communication in the form of annual financial and sustainability reports. There is no prescribed number of cases that should be included in a case study research, but having four to ten cases is advised [48]. The companies were selected on the basis of convenience sampling, either through earlier established contacts with companies, or based on accessibility to the case with limited resources and within the time frame [49]. However, the companies were listed based on predefined criteria that looked for manufacturing companies based in Scandinavia, companies with existing DfS focused products in their product portfolio, and companies with in-house product development activities. Thereby, the seven companies interviewed in this study present a homogenous sampling of companies with certain specific characteristics [50]. Additionally, four interviews were carried out with sustainability experts in the field of eco-design implementation for validating the findings from case companies. Among the interviewees from the case companies, seven respondents and their departments were directly involved in sustainability activities to a large extent as part of their work. Among the other departments that were represented in the interviews, product developers and project managers formed the next biggest group. The functions of other respondents varied between communication directors, EHS (Environment, Health and Safety) personnel, and R&D managers. The details of the respondents and case companies are further detailed in Table 1. The interviews were aimed at corroborating the literature findings and enriching them with real case experiences of implementing sustainability strategies in the product development and with statements of how the company context influenced the overall implementation process. Given the explorative nature of the study, semi-structured interviews were a judicious choice [46]. The interview questions were aimed at eliciting insight from the respondents into how DfS was implemented in the product development activities in the company, which factors in the company context influenced the implementation process, and how interactions within the company and between the company occur regarding the external actors on sustainability issues.

Table 1.

Interview respondent details, case company background, and number of interviews. EHS = Environment Health and Safety, R&D = Research & Development, CR = Corporate Responsibility, PM = Project Management.

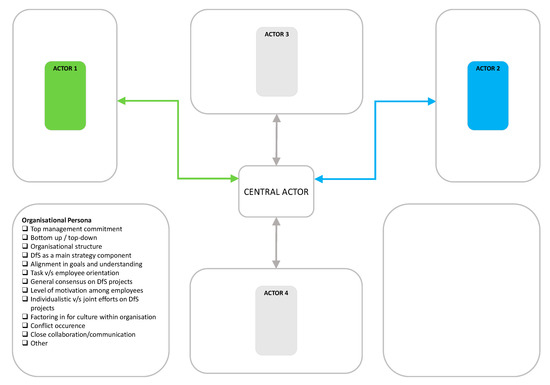

In order to further complement the data collection process and enrich the information gathered from case company interviews, we used an interaction mapper (Figure A1) that was designed to help the respondents graphically organize their thoughts, thus overcoming some of the commonly identified challenges in interviews such as losing the context of an answer [51], having difficulties verbally communicating one’s ideas [52], and factually disconnecting what they say and what they mean [53]. As can been seen from Figure A1, the map consists of five different boxes for actors, the central actor being the interview respondent and the four other boxes marked as Actor 1, Actor 2, Actor 3, and Actor 4, which denotes the departments or entities (external and internal) of the company with whom the respondent interacted during a DfS project. The points listed under “Organizational Persona” were used to guide the respondent on formulating their responses. While using the map, the respondent was asked to identify a set of actors that their department interacted with when it came to a DfS implementation project. Then, they were asked to pick two to four major actors and highlight the different factors that influenced their interaction with those actors during the implementation process. The identified actors included personnel, departments, project groups, different management positions within the company, suppliers, competitors, and customers. Post-its were used to note the observations made by the respondents regarding the factors that influenced their interactions.

3.2. Interview Analysis

All authors of this paper curated the interview questions jointly, and two of the authors carried out the interviews. Each case company interview lasted between 60–90 min. The interviews were recorded and transcribed using the qualitative data analysis software NVivo. As stated earlier, a combination of both deductive and inductive approaches [54] was taken while analyzing the data. Contextual factors of companies that influenced DfS implementation, as presented in Section 2, were probed for in the deductive part of the coding activity. Additionally, factors that emerged from the interview data were coded and analyzed in the inductive approach. The coded entities included words, phrases, or complete answers to interview questions that had key elements pertaining to the company context and its influence on the DfS implementation process. The results of the coding process are presented in Section 4.

4. Interview Findings

The factors illustrated in Figure 1 were used as points of departure in exploring the different possible dimensions of a company persona from the interview data. Based on this, 14 different dimensions were identified as relevant while defining the characteristics of a company persona. As can be observed from Table 2, the inductive approach from factors identified in Figure 1 and the deductive coding approach of the interview data showed a certain trend in the characteristics of the dimensions, namely factors that were partly or fully influenced by happenings/relations external to the company and factors that were solely by the company’s own function and style. Drawing inspiration from philosophy and metaphysics literature, these were categorized as extrinsic and intrinsic characteristics, respectively.

Table 2.

Description of the dimensions identified from the interviews categorized under extrinsic and intrinsic characteristics. E = Extrinsic and I = Intrinsic.

In philosophical studies, ascription of extrinsic characteristics to a product or entity is not entirely about the product or entity. Rather, it may well be part of a larger context in which the product or entity exists as a part [55]. In our context of companies, this could include factors external to the company that influence the company’s activities, such as product offerings, value proposition, and strategies. Contrarily, a “sentence or statement or proposition” that ascribes intrinsic properties to a product or entity is entirely about that thing [56]. In our context, this translates to the internal organization of the company, the DfS implementation process, and the functional goals to DfS, among others. Some of the factors identified during the literature review in Section 2 were found to have different manifestations in the actual company setting and were therefore constructed under different dimensions in order to define the company persona better. For example, the role that senior management has in relation to DfS implementation and the approaches they take (or do not take) to materialize their visions (if any) were some of the important factors mentioned in the literature reviewed. Analysis of the interview data revealed the different possible implications of senior management in practice, such as Board of Directors (E1) and History of the Company (E6). Section 4.1 and Section 4.2 explain how these 14 different dimensions—under extrinsic and intrinsic characteristics—were identified from the interview data.

Table 3 presents an overview of each dimension matched against the case companies where it was found to be an influential contextual factor in DfS implementation. These are marked as “x” in the table. Further, the final column of the table corroborates these findings with the inputs from sustainability experts (SE) who, based on their experiences working with companies, identified the most influential factors in a company involved in DfS implementation. As can be seen from Table 3, the identified dimensions have a certain level of interconnectedness among them. This is primarily because the company persona is a reflection of the company context, and the context is often dependent on factors that are important on their own, yet the context is also influenced by other factors of the company. For example, a company’s strategic focus, product offering, and company history influence its market conditions. Hence, the results presented in the following sections are an outcome of a coding process that looked for such factors, both independent and dependent, in defining the company context and should be read within this context.

Table 3.

Overview of persona dimensions as identified as influential factors in case companies and as experienced by sustainability experts. Dimensions that were identified to be significant in the companies’ DfS implementation context are marked as “x”. E = Extrinsic Characteristics, I = Intrinsic Characteristics.

4.1. Extrinsic Characteristics of the Companies

4.1.1. Board of Directors

Following our interviews with the SEs in the field, a prominent extrinsic characteristic that was identified by all four SEs was the role of the Board of Directors, especially in the context of medium and small-scale companies that are often family owned or partly owned by the workers. In such companies, SE1 and SE2 opined that DfS implementation in companies is a decision making process that necessitates larger commitments in terms of resources and time for the implementation process. Convincing the Board of Directors in most companies SE1 and SE3 worked with was the first step in establishing a sustainability strategy in the company. However, this characteristic was not evidently observed in the first cycle of coding case company interviews, primarily because they were all large companies. Nevertheless, following the observations from the SE interviews, the case company interviews were explored again for this dimension in a second cycle of coding, resulting in the findings presented below. For example, Company D, being a family owned company, had certain instances were family ownership roots of the company played an important role in sustainability issues, as can be seen from the quote below:

“Our stakeholder is a foundation that owns us and the family that established the company. And, as long as they agree with what we do, we are able to (sic). Moreover, we are economically sound company and we can put investments in to things we like to invest in. Of course we don’t have, I mean there are limited amount of money, but if we say, we want to do this and it is agreed upon by our board, we can go ahead and do it. Therefore, in that sense we are very fortunate and I know that the son of our founder he is not active in the business. However, he is very keen on these issues (sustainability). Him being there on the backseat somewhere, still overlooking what we are doing, that is also a big driver for us. And that is the charm of being in a family owned company as well.”(D2—Wood)

On the other hand, other larger companies, such as Companies A, B, C, and G, had the senior management (including the CEOs) as the more prominent decision making entity when it came to implementation of sustainability in product development.

4.1.2. Value Proposition of the Company

Companies tend to focus on different value propositions in their activities, which range from Product-Service Systems (PSS) to consultancy services. The nature of this value proposition is another important factor that helps define the context of the company. As all seven case companies were manufacturing companies, their biggest value proposition was the product itself. However, as could be observed in Companies A and C, the product itself could connote different priorities for the company. In Company A, the product was intended to provide the best user experience for the customer and had user comfort as a priority:

“No, it (sustainability) is not a main part of our strategy, the main part of our strategy is to make it easier for our users. Actually, we have our mission, vision and values here. And this is really, what is important for the company. It is making life easier for people with intimate care needs.”(A1—Pouch)

For Company C, in the renewable energy sector, the priorities were the efficiency of their product and the indirect sustainability benefit emanating from it in the form of lower cost, less wastage, easier transportation, and better functioning of the products:

“And you would see that we stand out looking into eco-design or what we found out is that development in our industry is driven by the levelled cost […]. So all we do is to minimize the cost and we do that natural thing in PD is to have less material because you need to buy that transport that, service that anything. So, that is the cost that every time we put a kilo on there is a cost associated with that. So Eco-design is not implemented in the way it is in some other businesses. Because […] setting targets will be outdated in 2 years times because our engineers outperform the targets that we dare to set for them.”(C1—Watt)

Whereas consumer goods manufacturers like Companies E, F, and G focused on maintaining their performances with successful products, which was followed by introducing new sustainable alternatives or improving the existing products with respect to sustainability. Company B and Company C had more B2B (business-to-business) contexts, and the value propositions were quality products with certain indirect sustainability benefits, such as lower energy consumption and longer durability while using their products.

4.1.3. Drive of the Company on DfS Issues

Another significant extrinsic characteristic of the company identified was the drive of the company in sustainability activities. The case companies interviewed were invariably focused on the prices of their products and ensuring compliance with the legal requirements. Given the nature of the industry, the cost factor was more prominent in consumer goods companies such as E and G. Company E had strong influence from competition, making it more wary of the costs involved in the products, as can be seen in the following quote:

“But most often, if they (marketing and supply chain) don’t find it most relevant for the consumers or so, it might be that it costs, and if we should really do that. But, if it is something that we have to do anyways (compliance), that is not part of this. This is more kind of questions where you actually have to go one step further. These kinds of projects I am talking about (that are not the common ones).”(E1—Vitamin)

While in Company G, sustainability was very much linked to how it translated to increased sales:

“I think you can see that for management sustainability is important part. But if the link to that is to increase sales, it is a longer link. So, to be able to see that link, I think is important and we felt the link tougher than may be how they have seen it.”(G2—Soap)

At Company D, even though cost was the most important driver in the company, there were certain product development projects under process where the sustainability (in the form of material and energy consumption) was prioritized over other factors:

“Many of our PD projects have energy performance as their only focus and then you have quality, delivery, price and then you have some market relevance like color, sizes or whatever. But energy performance is the main in eco-design. And that is formalized very much so. We have colleagues in R&D dept. who work on it.”(D2—Wood)

In addition, other major factors driving companies on sustainability were identified from the interviews with experts—namely philanthropy (SE 2), CSR initiatives (SE3, SE2), compliance with legal and regulatory norms (SE1, SE3, SE4), and total sustainability in its activities (SE4, SE3). None of the case companies were found to have an existing total-sustainability agenda.

4.1.4. Strategic Focus of the Company

Defining a clear sustainable strategy often helps companies in prioritizing DfS activities [29]. However, the interview results show that defining such strategies could range from general statements to setting clear operational goals in the day-to-day functioning of the company. Company B was observed to have clear goals and targets on sustainability topics and ensured that these were followed up at each stage in the company’s product development process. Such an approach helped the company in prioritizing sustainability issues and in decision making related to product development practices:

“I do think that it is the right approach (to have strategic focus). Because, if it is not a top down, it is really hard. It is really hard to go bottom up, I can tell you from experience. Of course you can try to push in the doors, but without management commitment. […] So, if you are not being told that this is your target and this is your agenda, you need to make sure that you develop some sustainable product or you engage customer on these topics, you won’t prioritize it.”(B1—Microbes)

Whereas Companies E and G had sustainability goals and targets, as communicated from their corporate level, and needed to translate those to match their product development activities. This translation often needed more resources to tailor the corporate level strategy to the company level:

“I think the key is the understanding and strategic planning for this, it is what is lacking, for us because we have worked on and have launched just before summer our sustainability strategy which said about where we are going. So when we have a structure which says about where we are going, you can all go in the same direction and make tools and good goals for going in that direction. In addition, that has been lacking last years. So we didn’t know where we wanted to go and it is hard to get funding when you don’t have a plan and a reason for why you need it.”(G2—Soap)

The interview results also showed that certain companies could spend considerable time and resources in developing a consensus around the sustainability strategy of the company, as was the case with Company F. This mutual understanding of setting sustainability targets and goals helps companies incorporate them more systematically into each department’s activity and overcome the challenges associated with sustainability understanding in the company, as highlighted in Section 2. Such an approach to sustainability strategy also equipped Company F to provide general guidelines to its departments—rather than rigid structures—thus providing the latter with sufficient freedom to operationalize the sustainability strategy as per its context:

“First solution was to develop the sustainability strategy. Which we did through a very thorough process. I think we actually spent 1.5 years on this strategy process. We involved of course all the functions, but also all the key persons in the companies. So then, the strategy was sent to be approved by the board of directors. So then, when we had agreed on the targets, it was easier to go with a specific agenda to the management teams of the business areas of the companies.”(F2—Food)

Another company characteristic observed in sustainable strategies was how the business context of the company influenced the priorities of the company in relation to sustainability topics. Given the unique customer base of Company A (mostly patients with serious illnesses), despite acknowledging the need for more sustainable product solutions, the company had a clear focus on prioritizing the user experience above all the other aspects. Such a focus also awarded Company A a formidable position in its market:

“And I think that (sustainability strategy) basically boils down to what you think. I think the major part of the work we do here, is because, we like to make people better and help them the best we can. So that will basically change what you are doing. On the other hand, we are looking to substitute some of the worst candidates away. On a long term.”(A3—Pouch)

4.1.5. Market Conditions

As all the interviewed case companies were manufacturing companies, the market conditions surrounding their product offering were found to have strong influential roles in the DfS implementation process that was adopted. Companies such as E, F, and G experienced a strong pull for greener products from their customers, necessitating changes in the product portfolio of the companies. Another aspect observed regarding market conditions was the strong role that marketing and sales departments play in highlighting and driving new initiatives in companies. As the marketing department forms the interface between the company and customers, they have a bigger say in project meetings. In Company G, the marketing department was always the project manager in all product development projects:

“I work closely with them (marketing department). So, at the moment, they have, they see the need in the market and there is the white spot on sustainability. So for them also to, they are very enthusiastic when you are presenting solutions to them. Moreover, I think it is good communication that makes it also easier and I have worked with marketing so I see also their struggle. I know what they are facing and what they need in a way.”(G2—Soap)

In certain other company contexts, such as in Companies A and B, the utility and efficiency of the product was most demanded for, and the product development activity was fine-tuned to ensure that those issues—as flagged by their respective customers—were addressed. This included better durability of their medical products, ease of use and disposal, ensuring high quality, and ensuring a low risk of product failure in the case of Company A. Similarly, in Company B, such demands translated to adaptive solutions in biotechnology that could be used for the specific needs of customers (companies), such as lowering energy requirements and increasing the efficiency of the end products. Such requirements necessitate that Companies A and B choose suppliers that can ensure a sustained supply of raw material for a long term over smaller suppliers that can supply sustainable alternatives:

“Always this high in (product development) process is the (importance of) whole supplier demand. As in, we would like to have materials that can be readily sourced, so if it is more likely to have more sourcing options, that could also be one way that we say, OK, there is potentially an environmentally better option here. But if it is only a small supplier and it is only one in the world, whereas there are two large suppliers that can supply us, we might actually decide to go with the one and based on the fact that we would like to have the steady supply of materials.”(A3—Pouch)

Another important market condition that was observed in Company D was the high price competition that exists in the construction industry. Thus, the customers of Company D had more alternatives to choose from, making them more conscious of the price rather than the sustainability credentials of the product. Therefore, the company must look for more sustainable alternatives without increasing the price of their products to a level that is unattractive to the buyers:

“I had actually some workshops with our market people here and it’s not that our market (is green conscious), that our way of selling things is not really (based on) a green stamp or a green swan. It (eco-labelling) is not anything that can bring our sales up or can justify a higher price. If you have two products and the price were the same, then the customer would choose the one with the green stamp. But the customer from our market sales’ perspective, our feeling is that customers are not willing to pay (extra) for a product with a green stamp.”(D1—Wood)

4.1.6. History of the Company

A few of the interviews highlighted how the history of the company was a factor in the sustainability activities of the company. At Company C, the primary business model is to develop and deliver products that cater to renewable energy production. The indirect benefit stemming from this business, according to one of the respondents, is greener energy in the world and a lower carbon footprint. Thus, the historical trend existing in the company has been to make its products more efficient in delivering more energy output in the use phase of the product:

“It’s (eco-design) already happening without it being called eco-design or before we are setting targets specifically to reduce waste. Coming in from a cost-target perspective in getting this level-ised cost of energy down and somehow our product is being innovated in ways that also have an add-on benefit for the environment (green energy) so there is not the need to do these eco-design projects (specifically) because so much is already happening.”(C1—Watt)

Similarly, at Company D, the product offering has helped in improving the indoor living quality of commercial and residential buildings. A focus on improving the indoor living quality has been a primary focus of the company right from its beginning, translating indirectly to sustainability benefits for the end user of its products. Such an approach encourages both Companies C and D to further work on the technicalities of their product. However, it does not necessarily create a need to reduce the footprint of the production process or to look for more sustainable raw materials in the product development process:

“It (Sustainability in Product Development) depends a little bit how you look at it because if you say eco-design project, we have a lot of focus on the properties of our product. [..] So in that terms we have a lot of focus on the eco-design if you look at it in the way that we produce products that will save energy in your house so it’s a little bit how you look at it because that has a great focus through the whole project. So, that’s my point and it is the whole idea about our products actually so that is a very natural thing that is the driver (for DfS) in our products.”(D1—Wood)

Interestingly, as mentioned in Section 4.1.4, at Company F, the focus on sustainability is rather recent and the company is working on operationalizing its sustainability strategy. Nevertheless, as pointed out by one of the interview respondents, the presence of harmful chemicals and hazardous raw materials necessitated that Company F look for safer and more consumer friendly alternatives before establishing a sustainability strategy. This underlines the relevance of company context and history when considering product offerings and sustainability issues:

“We have a long history of product development to reduce their environmental impact. So that is not something that is new to them (and has existed before the sustainability strategy). And earlier I guess, it has been the Product Development Department. or a similar department like it (that had an) important (role) in putting this on the agenda.”(F2—Food)

4.1.7. Risk Sensitivity

Risk sensitivity was another important topic discussed during the interviews. The interview analysis showed that risk sensitivity of the companies related mostly to the external environment of the company, specifically in relation to its responses when compared to competitors and market conditions. Consequently, risk sensitivity is an extrinsic characteristic in the company persona. The case companies tended to take a “watch and replicate” approach when it came to launching new DfS products in their markets. Some of the respondents identified the following reasons for such an approach: the inherent risk of losing their existing customer base, the huge initial investment involved in developing and marketing new products over existing ones, and the lack of short term returns or results. This is very rightly reflected in the following quote from Company D:

“But when it comes to doing something new, taking risk, adding cost, the answer is no […] So that is why it’s complex. It is not like a problem because they (senior management) are very supportive. The management really wants to do the right things, also about thinking green. But it’s always a balance, and uh a balance of risk if you go into new things, new materials.”(D1—Wood)

Further, the companies were also concerned about the long-term investments the project needed and the risks involved in being the first mover on environmental issues and investing in DfS:

“This project “X” we had, that was with a lifetime of 30 years, which is very long, and that was why that fell to the ground, because OK 30 years, we don’t know whether we would have those sites in 30 years. So, that was way too long. So, I think if I can come up with a project with a payback time before 2020, I think that will go through, but that is not the case at the moment.”(A1—Pouch)

“That is how we see it and we don’t have to be front runners and sometimes that is a good when you are looking at environmental issues. Because it can be very expensive to be the front-runner. Moreover, when you are doing projects/products that have a long lifetime. Like, you don’t want to put something in your home that might damage in half a year right? It is expensive; you do not buy that many products in your lifetime.”(D2—Wood)

Consumer goods companies such as Companies E, F, and G often based new product launches on their ongoing product development processes or looked for successful solutions from larger players in other geographic markets in the rest of Europe and the world. These observations from the interviews point to the need for evaluating the risk-taking nature of the company while also understanding its context from a DfS implementation perspective.

4.2. Intrinsic Characteristics of the Company

4.2.1. Senior Management Approach to DfS

The way the senior management in the companies approached the topic of sustainability was found to have a meaningful impact on the whole implementation process. All the case companies that were interviewed invariably acknowledged the need for sustainability in their activities and mentioned that their senior management also held similar views. However, this commitment from senior management towards sustainability implementation was observed to be different in each of the companies. While some of the case companies already had very well established positions in senior management that focused on sustainability activities, others had it embedded with other management responsibilities, presented as a sub task for the EHS department. At Company F, the sustainability strategy was developed in close association with the senior management, which made anchoring the sustainability activities much easier in the group and the business units under it:

“They have used time to develop their own sustainability strategy so I think is has been a very good process together with them and the whole management team involved with the work. It has been much better anchored with the management team.”(F1—Food)

While at Company A, given the nature of its products and its priorities of providing better service to their customers, the management often prioritized using the best material possible for their products, and sustainability was only indirectly prioritized in the product development process:

“But in the end, if your alternative gives a less good user experience, then you have to prioritize between what you are doing...so in that sense, that is why I said there is a lot of conflicts. Because we have these kind of situation (market case) and as long as we are within the boundaries of what we are doing, are we use rules and discuss with our colleagues that we do the correct choices, or the best choices, then basically they are OK with that.”(A3—Pouch)

Not having the necessary senior management support and follow up often made it difficult for companies to proceed with the implementation of sustainability aspects in their products. This also meant that the senior management needed to be updated on the changes being implemented and how they delivered economical and environmental returns to the company. A case example from Wood can be seen in the following quote:

“By the end of 2014 we started the analysis […] and we addressed assessing Circular Economy (CE). Our management group, they are like, 6 of them I think, half of them forgot what they had approved. So they were like... NO you shouldn’t do CE and we had a lot of a big hurdle to get this analysis started. So, it (the senior management) was a very complicated group to handle because they are management, they have a lot of opinions, they are very fast. They don’t have time to actually sit down and listen to context or... On the other hand, if you don’t have their acceptance on what you are doing, you will get nowhere.”(D2—Wood)

Further, some of the senior managements were strongly driven by “the global sense of economics”, i.e., unless there was a clear business plan for any investment being made on sustainability topics, it would be hard to prioritize DfS in the company’s activities. These observations definitely underline the importance of understanding the role and attitude of senior management in sustainability topics in a company while trying to define its company persona.

4.2.2. Organizational Constitution in DfS Activities

Another important extrinsic dimension observed from the interviews was the way people and departments were organized in the company. Some of the case companies had sustainability departments that oversaw all sustainability activities in the company, whereas others had sustainability as part of the R&D department in the company or embedded in the EHS department. Having a complete overview of sustainability activities helped companies push for the changes needed in product design and development more easily than when it was just an additional task within R&D or EHS. At Company B, the sustainability development group that was anchored as part of the senior management oversaw the sustainability activities. This bridged the communication gap between the sustainability activities in the company and the strategic decision making process happening within the senior management of the company:

“I think that (to be anchored within senior management) has been an advantage, allows us to work across. Which is really super important. I don’t really know where else should we be really anchored. Of course, I would think we could be anchored in project management or in marketing. But that would make it more difficult for us to work across the depts. Like in any environmental/ sustainability department, we need to work across.”(B1—Microbes)

Company G had a very top down management style where the decision making was time consuming and the lack of overview and absence of a sustainability department often made it difficult to communicate the importance of different sustainability actions to the management:

“Yeah, that (department constitution) is one thing and also we are quite hierarchical (sic) so, every decision takes a lot of time. Moreover, when we are trying to have, for example. sustainability strategy, we would need a budget and when it takes may be 4 months before you get an answer whether we can have the money or not, because it is all this layers.”(G1—Soap)

At Company F, the senior management provided guidance on sustainability matters to the different business units below it and thus followed a decentralized structure on DfS implementation:

“Then it is a decentralized structure. So I, don’t have authority, we don’t want to be normative. Nevertheless, we want to inspire, guide and discuss with each companies’ management team. But at the end, what a unit does will be decided by the management team of that company. So in order to implement the sustainability strategy, there is a need for all of these departments.”(F2—Food)

At Company C, the flat cross-functional teams collaborated closely with each other on DfS projects, making it easier to learn from each other and communicate the expectations from projects among themselves more effectively. Such a flat structure of project teams also helped the company bridge the communication gap between project teams located at different offices of the company:

“You have a directional system for products, for marketing, for manufacturing and in those directional systems you have managers that go across different functions to coordinate. So of course we have a hierarchy, but we don’t have to go up and then go down to get a decision from the management. We can go directly from our department to another and say, well because this and that we have to do like so. So, it is a flat structure.”(C2—Wood)

4.2.3. Degree of Formalization in DfS Implementation

Researchers earlier mentioned how the level of formalization can influence DfS implementation in companies [31,57]. The interviews showed that each of the case companies approached DfS implementation differently. A major distinction can be drawn between the formalized and in-formalized approaches to DfS implementation. Stage gate models, checklists, feedback loops, and additional tools (such as LCA in the PD stages) supported the formalized approach. Setting general guidelines and requirements, ad-hoc measures, and client dependent evaluations of the product’s sustainability characterized the informal approach. At Company B, LCA was used early in the product development phase to provide a rough estimate on the environmental impact of the product and later again in the stage gate process to evaluate the actual impact of the process. However, these steps are also client dependent in some cases, and the respondent mentioned the need for ensuring that it is followed in all project teams unanimously:

“We have a much formalized process here, so called stage gate model. The development projects are being set up that way all. […] LCA is integrated in that process. We have two entry points, one at the very early stage. […] As soon as the concept is ready in early stage, we usually enter into the project and try to make these initial assessments. Because already at an early stage it could be beneficial for the project to know if we have a very good sustainability story here? But once we had identified in the early stage that we have some sort of sustainability benefits, then we can pursue these during product development and make sure that we collect wide range of LCAs to take place towards the end (of stage gate process).”(B1—Microbes)

Meanwhile, respondents from Companies E, F, and G mentioned a more informal approach to DfS implementation. As mentioned earlier, Company F had a practice of providing guidance on DfS projects rather than strict structures for the implementation process. The respondent also mentioned how they provided support on LCA for the company’s units who wanted to carry out an analysis based on the sustainability guidelines provided to them. As Company F was in the early stage of DfS implementation, this need-based approach was a good start for the company, rather than enforcing eco-design tools for all projects:

“It’s like setting the directions for the company, giving guidelines or giving requirements from senior management to over units (sub-business units) and how to work with and what we mean should be in place. It is like setting the directions for them, giving guidelines or giving requirements from the senior management to over organizations and how to work with and what we mean should be in place. Yeah there have been questions from some of the units about doing like life cycle assessment. That’s where I have been involved to support them in how to do this, to find out how to do it, could there be someone that can support them and to understand more the theories behind using those types of tools.”(F1—Food)

At Companies E and G, the respondents observed that there was a need for eco-design tools and methods, as well as a need for competence within departments to use it. The companies were in the early stages of their sustainability journeys and found it difficult to operationalize their strategies without sufficient resources in the form of tools and methods:

“No tools or any standard formula, we don’t have it. We are not that far, we want to be there. I hope we come there. We started that discussion what should be our main setup, if to be honest every single project should include one or another element where we take care of sustainability. It might be environmental, health or combination. But we are not there today, but we have several projects going on having environmental elements.”(G3—Soap)

“As it has been so far, it has been mostly about convincing the right people, but what we want to have is to agree to (certain structure). When we choose people to do this (DfS) projects, we choose different departments and the relevant ones. Therefore, what we want to do is a sort of 4–5 guidelines that you should always consider in an innovation process or communication or other things, you should always consider that. [..] Therefore, I think that is the starting point. But, when it comes to seeing how we can be more effective, that is where we could be more eager, or have higher expectations on ourselves, to deliver more on being through sustainable choices. So it has been more ad hoc in the way we have introduced these subjects, but what I really believe in is that, we have to write a lot of theses. You don’t succeed in doing do it, if you don’t have it as part of the structure. What kind of question should you ask when you come this kind of product? Yes, you should ask these, these and these questions and those sustainable questions that should in that level. So that the different departments have to go through that gate. Are we willing to take a kind of reputation risk or do we want to see that X or Y happens? So that we are responsible (in DfS projects). And I think that natural or routine guidelines in that level is important, if not it is more accidental.”(E1—Vitamin)

Thus, the level of formalization (or lack of it) in DfS implementation in companies was found to be an important intrinsic characteristic in defining the company persona.

4.2.4. Sustainability Definition

Another important characteristic observed in the companies was how the term sustainability was defined within the company context. At Company D, the respondent opined that terminologies such as Design for Sustainability or eco-design were not commonly used in the company, thus often created an ambiguity in the usage of the phrase in project teams:

“And we could also continue developing the language that we use about it. Because when you say “eco-design projects”, it’s not a word we use in here (at the company). So we could work further on a common language because there are many different words flying around in the media, but what is actually a green product or a sustainable product? What is it actually? It is very different what people understand by that.”(D1—Wood)

At Company F, the respondent received requests from units on how to proceed:

“It has been overwhelming for us, taking sustainability on-board. So they (units) are asking me, what do you want us to do? Please tell us there are so many topics, we don’t know what to do and what should we focus on. So, that was actually why we tried to develop the common sustainability strategy to try and define all the different topics and make it easier.”(F2—Food)

Further, in the interviews with sustainability experts, SE4 opined that there is a difference between the definition of sustainability and understanding what it means in a company context. Often, well-defined and communicated sustainability goals are not understood in the same manner among the employees due to the differences in educational background or individual perceptions. This difference was also observed in the case company interviews and is further elaborated in Section 4.2.5.

4.2.5. Sustainability Understanding

The interviews showed that, most often, the way sustainability was defined in the companies could be understood differently by different departments or individuals in the company. Another aspect to this was the awareness surrounding sustainability topics and how it was acknowledged in the product development process. F2 mentioned how it was difficult to convince and talk with colleagues about the need for integrating sustainability a few years ago, and how it changed recently with clearer goals and increased awareness in the company:

“I talked with them (colleagues) four years ago but this (increased awareness) is something new which I think makes it easier now. Because now I know where I am going, I know that I’m going to launch a product with recycled materials. Hence, it’s easier to discuss with them, they’re already in that area and have a lot of competence, and I need that competence and understanding to make it work.”(F2—Soap)

At Company B, sustainability was very much top-down driven and was successful in imbibing DfS focus in product development practices. However, Company B also lacked a comparable understanding of sustainability issues within departments that were on the “business side” of the company, such as sales and marketing:

“I think we have been, that we have integrated the way (for sustainability), or may be in the past, there wasn’t this intensity with the corporate sustainability standing alone, sitting in the ivory tower. I think we are definitely working towards bringing sustainability more out at the practical side in the business. That is where it can be a huge challenge. I think we have managed really well in the PD. May be next step is to manage equally well with the marketing department.”(B1—Microbes)

At Company E, due to the absence of a common understanding on sustainability topics, it was difficult to convince and educate departments on the certifications needed and raw material selection criteria pertaining to sustainable sourcing:

“So it (sustainability understanding) is more about wider areas to cover. So, if you talk about sustainability in total about the raw materials here, there are many (sustainability) factors (involved). To get them (departments) understand better what is the difference between those and why is it not possible to have one certificate or some raw materials is difficult currently.”(E2—Vitamin)

4.2.6. Functional Goals in DfS

A general trend observed in the case companies was the situational versus planned and systematic improvements on the sustainability activities of the company. Company A resorted to making situational improvements to their products potentially possible without disrupting the utility of the product. Such an approach was needed for the company given its niche business area, as explained earlier:

“We don’t have any formulated target on environmental improvements in the process, other than we want to evaluate it and we want to you can say we want environment to be part of the decisions. But we have not defined that we always want to take the greenest solution per se. And this is our main driver. And if we can combine that with a good environmental solution then we would like to do that. But the main driver is the solution. So that is really our passion. So it’s actually more the social part you could say. That’s the driver.”(A2—Pouch)

At Company D, a new organizational unit was formed exclusively to source for new raw materials to replace the existing ones in their products. Sustainability was also included as one of the evaluation criteria in this new sourcing process:

“This spring, I was changing my position from the development department to a new part of our organization, where we want to be a little more ahead of the development in terms of finding new materials or combinations of materials that can be used for new products.”(D1—Wood)

4.2.7. DfS Chaperoning

Another important intrinsic characteristic was the entity that drives the sustainability activities within the company. We termed this DfS chaperoning and found it to be eco-champions in companies, certain departments or indirect stimuli from external actors in the form of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO), or environmental activists and consultants. Companies acknowledged that these entities with high motivations played important roles in establishing, executing, and following up sustainability goals in the companies. At Companies D and A, this was observed to be individuals pushing bottom up for sustainability focus in the company. These eco-champions pursued the sustainability agenda actively in the product development process:

“So I think it’s a movement (sustainability focus), it’s something that is maturing along as we get more knowledge. Putting the focus on sustainability, building it in in the presentation that we show to the management. Yes I would say that it is individuals, there are also some specialists that have a green focus that contribute so yes I would say it is individuals (chaperoning the process).”(D1—Wood)

A1 narrated a similar incident in the following quote:

“I try to give a speech in a start-up project, I ask for 5–10 min, where I deliver the main issues that could be from our yearly environmental report. But it could also be like mass flows, pointing out the importance of environmental issues. Ok, we produce so much waste, but the waste we produce PD has been the same since 5–10 years ago. That is because we still produce these products and they still involve these waste. So, that is my key point, OK, so we really like to reduce waste and energy consumption is important for our whole CO2 account. It is now that we have to do it.”(A1—Pouch)

While at Companies E, F, and G, this was found to be external stimuli in the form of international collaborations with environmental agencies or companies themselves acknowledging the need for it along the whole value chain:

“As an administrative body we collaborated with the UNDP. So we developed together a project description, a concept description of the different types of activities that we believed needed to be taken in order to really lift the sector (sustainability in the whole value chain).”(F2—Food)

5. Discussion and Analysis

The use of personas in design projects and research helps in bridging the gap between the actual and presumed needs of the user. The use of personas is intended to inform designers on how to target their design activity. The extreme user archetypes sketched using personas help get the designer closer to the actual user [15]. Translating this to the context of this paper, company personas should help researchers and consultants in sketching and understanding the user, or in our case, the company, better and more closely. Hence, it is interesting to understand how the 14 dimensions could equip this target audience with inputs on how to construct company personas. A user persona is typically based on characteristics such as the demographics of the user, fears and aspirations, needs and expectations, product use patterns, among others [15,19]. Similarly, the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics observed from the empirical results provide a similar perspective of the company. Dimensions such as Board of Directors (E1), market conditions (E5), and the history of the company (E6) can be directly related to the demographics of a user. Similar comparison can be drawn between the views of the user [22] and risk sensitivity (E7), senior management approach (I1), emotional aspects, and DfS chaperoning (I7). These cross comparisons are further illustrated in Table 4. Therefore, based on the empirical results retrieved from the coding process, it is these 14 dimensions that can be corroborated with the user persona characteristics discussed in Section 2.

Table 4.

A proposal for mapping commonly used user persona characteristics onto company persona dimensions, as identified from the interviews. E = Extrinsic Characteristics and I = Intrinsic Characteristics presented in Table 2.

5.1. Constructing Company Personas

Creating consensus among the stakeholders regarding the accuracy of the created persona is an identified challenge in design studies [59]. In order to overcome this, Miaskiewicz and Luxmoore [22] proposed a data-driven approach to creating personas and enhancing the organizational adoption of it. Adapting from this approach, we propose a four stage process of creating company personas:

- Create an inventory of necessary sustainability attributes of the company.

- Characterize the company based on the attributes along the 14 persona dimensions.

- Incorporate additional inputs about the company through qualitative techniques such as interviews and action research.

- Create the individual company personas by incorporating the initially identified attributes and input from Stage 3.

Applying this four stage process to the empirical data collected from the case companies, the authors observed certain overlap among the companies’ attributes. Based on these inputs, we propose the following four personas to give readers an impression of a company persona as we envisage it.

Thus, as seen in user personas, the four stage process combined with the 14 identified dimensions could potentially develop company personas that highlight the niche characteristics of the company context from a DfS perspective. As can be observed from Table 5, such a description imbibes factors that were already widely discussed in literature as well as factors less addressed, such as risk sensitivity and the drive of the company.

Table 5.

Persona samples extracted from case company interviews. Case companies matching the persona description are provided in parentheses. PD = Product Development, R&D = Research and Development, CE = Circular Economy, B2B = Business to Business.

5.2. Implications of Company Persona Dimensions