Beyond Place Attachment: Land Attachment of Resettled Farmers in Jiangsu, China

Abstract

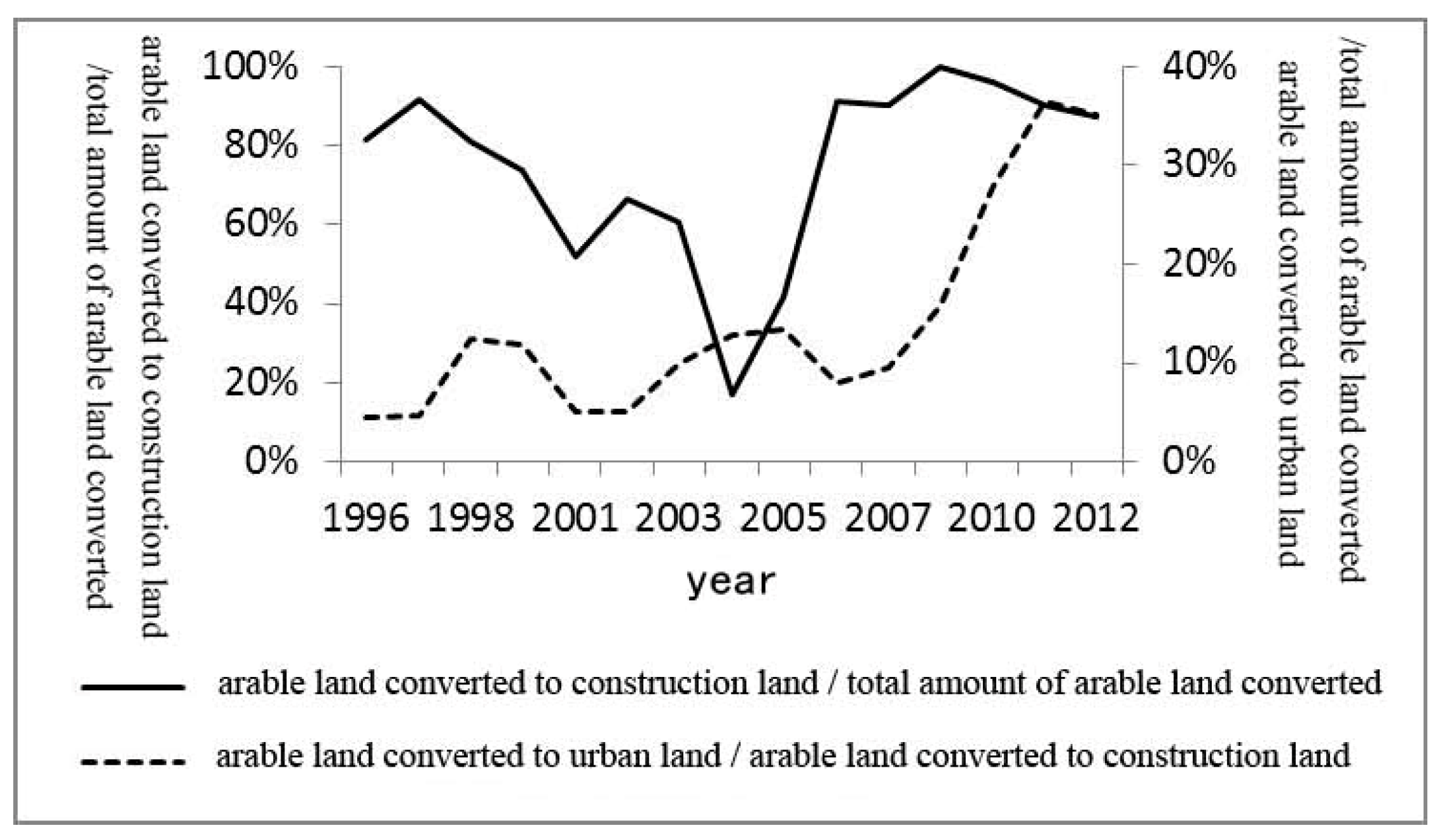

1. Introduction: Farmer–Land Relationship and Land Attachment

2. Exploring Land Attachment: Methods and Study Area

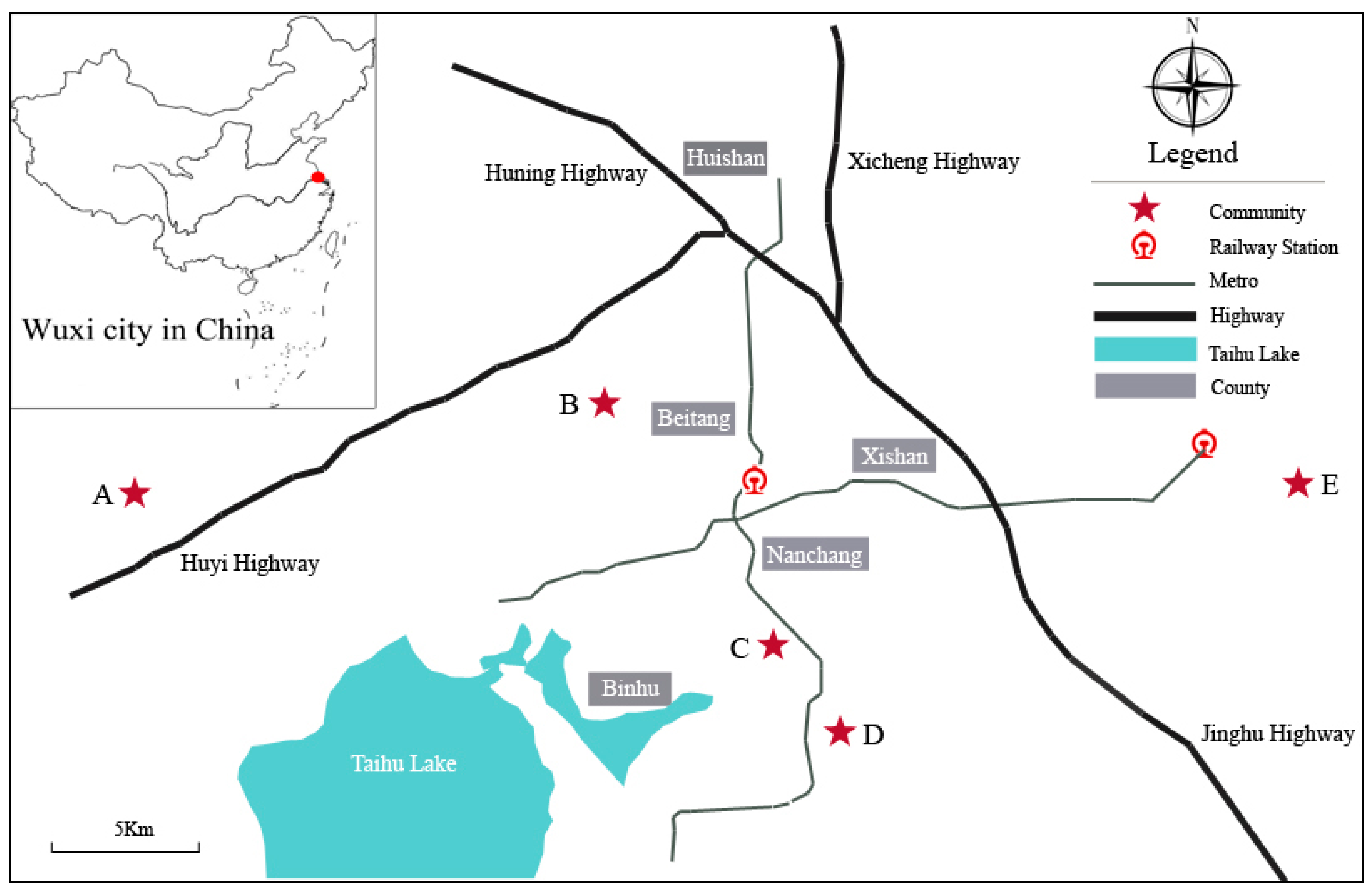

2.1. Study Area

2.2. In-Depth Interviews

2.3. Data Categorization and Analysis

3. Unpacking Land Attachment

4. Different Types of Land Attachment

4.1. Reluctant to Give Up Rural Land and with Land Attachment

4.2. Willing to Give Up Rural Land but with Land Attachment

4.3. Willing to Give Up Rural Land and Without Land Attachment

5. Discussion

5.1. Land Attachment and Place Attachment

5.2. Policy Implication for Sustainable Policy/Community Development

5.3. Limitation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, G.C.S. China‘s landed urbanization: Neoliberalizing politics, land commodification, and municipal finance in the growth of metropolises. Environ. Plan. A 2014, 46, 1814–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Kuang, W.H.; Zhang, Z.X.; Xu, X.L.; Qin, Y.W.; Ning, J.; Zhou, W.C.; Zhang, S.W.; Li, R.D.; Yan, C.Z.; et al. Spatiotemporal characteristics, patterns and causes of land use changes in China since the late 1980s. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2014, 69, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Chen, M. Several viewpoints on the background of compiling the “National New Urbanization Planning (2014–2020)”. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2015, 70, 179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Antrop, M. Changing patterns in the urbanized countryside of Western Europe. Landsc. Ecol. 2000, 15, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, M.J. Displacement and identity discontinuity: The role of nostalgia in establishing new identity categories. Symb. Interact. 2003, 26, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Wang, J.Y.; Long, H.L. Analysis of arable land loss and its impact on rural sustainability in Southern Jiangsu Province of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, H.L.; Liu, Y.S.; Li, X.B.; Chen, Y.F. Building new countryside in China: A geographical perspective. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnet, I.C.; Pert, P.L. Patterns, drivers and impacts of urban growth-A study from Cairns, Queensland, Australia from 1952 to 2031. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H.; Stewart, S.I.; Bengston, D.N. The social aspects of landscape change: Protecting open space under the pressure of development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 69, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.J.; Ng, C.N. Spatial and temporal dynamics of urban sprawl along two urban-rural transects: A case study of Guangzhou, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 79, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.M.; Guo, Y. Rural development led by autonomous village land cooperatives: Its impact on sustainable China’s urbanisation in high-density regions. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 1395–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T. Proenvironmental Behavior: Critical Link Between Satisfaction and Place Attachment in Australia and Canada. Tour. Anal. 2017, 22, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Zhang, P.; Lo, K.; Chen, T.; Gao, R. Age-differentiated impact of land appropriation and resettlement on landless farmers: A case study of Xinghua village, China. Geogr. Res. 2017, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.E.; Dai, H.J.; Li, M.T.; Li, M.S. Personal networks and employment: A study on landless farmers in Yunnan province of China. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work 2018, 28, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.J.; Liu, Y.T.; Webster, C.; Wu, F.L. Property Rights Redistribution, Entitlement Failure and the Impoverishment of Landless Farmers in China. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1925–1949. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, J.I. Care and stewardship: From home to planet. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveit, M.; Ode, A.; Fry, G. Key concepts in a framework for analysing visual landscape character. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho-Ribeiro, S.; Ramos, I.L.; Madeira, L.; Barroso, F.; Menezes, H.; Correia, T.P. Is land cover an important asset for addressing the subjective landscape dimensions? Land Use Policy 2013, 35, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, C.E.; Halfacre, A.C. Place Matters: An Investigation of Farmers‘ Attachment to Their Land. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2014, 20, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhorst, A.M.; Hoon, C.; le Rutte, R.; de Snoo, G. There is an I in nature: The crucial role of the self in nature conservation. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.L.; Green, J.D.; Reed, A. Interdependence with the environment: Commitment, interconnectedness, and environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manstead, A.S.R. The benefits of a critical stance: A reflection on past papers on the theories of reasoned action and planned behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 50, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildenbrand, B.; Hennon, C.B. Above all, farming means family farming: Context for introducing the articles in this special issue. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2005, 36, 357–366. [Google Scholar]

- Flemsaeter, F. Home matters: The role of home in property enactment on Norwegian smallholdings. Norsk Geogr. Tidsskr 2009, 63, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehne, G. My decision to sell the family farm. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 30, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, L.; Meurk, C.; Woods, M. Decoupling farm, farming and place: Recombinant attachments of globally engaged family farmers. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 30, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.P. Community and Land Attachment of Chagga Women on Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. All Theses and Dissertations, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kaida, N.; Miah, T.M. Rural-urban perspectives on impoverishment risks in development-induced involuntary resettlement in Bangladesh. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J. Effects of Involuntary Residential Relocation on Household Satisfaction in Shanghai, China. Urban Policy Res. 2013, 31, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, F.; Wuzhati, S.; Wen, B.F. Urban or village residents? A case study of the spontaneous space transformation of the forced upstairs farmers’ community in Beijing. Habitat Int. 2016, 56, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Weiler, B. Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: A structural equation modelling approach. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977; 235p. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.; Uysal, M. Social involvement and park citizenship as moderators for quality-of-life in a national park. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, G.H.; Chipuer, H.M.; Bramston, P. Sense of place amongst adolescents and adults in two rural Australian towns: The discriminating features of place attachment, sense of community and place dependence in relation to place identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, B.; Martin, A.M.; Ruiz, C.; Hidalgo, M.D. The role of place identity and place attachment in breaking environmental protection laws. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar]

- Heacock, E.; Hollander, J. A grounded theory approach to development suitability analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.F.; Kang, J. A grounded theory approach to the subjective understanding of urban soundscape in Sheffield. Cities 2016, 50, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R. Testing the dimensionality of place attachment in recreational settings. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentella, Y. Developing a Multi-Dimensional Model of Hispano Attachment to and Loss of Land. Cult. Psychol. 2009, 15, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, S.; Ujang, N. Making places: The role of attachment in creating the sense of place for traditional streets in Malaysia. Habitat Int. 2008, 32, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, S.; Mazumdar, S. Religion and place attachment: A study of sacred places. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Lockwood, M. Forms and sources of place attachment: Evidence from two protected areas. Geoforum 2014, 53, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasarda, J.D.; Janowitz, M. Community attachment in mass society. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1974, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudy, W.J. Further consideration of indicators of community attachment. Soc. Indicat. Res. 1982, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalli, M. Urban-related identity: Theory, measurement, and empirical findings. J. Environ. Psychol. 1992, 12, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Huang, X.; Chen, Z. Preliminary Study on Sustainable Livelihoods Evaluation of the Peasants Involved in Land Expropriation. China Land Sci. 2008, 22, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Yao, P.; Huang, X.J.; Chen, Z.G. Sustainable Livelihoods Evaluation of Land-lost Farmers Based on Fuzzy Matter-element Model: A Case Study of Nanjing. China Land Sci. 2013, 27, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, P. Towards a developmental theory of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.; Beckley, T.; Wallace, S.; Ambard, M. A picture and 1000 words: Using resident-employed photography to understand attachment to high amenity places. J. Leis. Res. 2004, 36, 580–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Bricker, K.; Graefe, A.; Wickham, T. An examination of recreationists’ relationships with activities and settings. Leis. Sci. 2004, 26, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesch, G.S.; Manor, O. Social ties, environmental perception, and local attachment. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, K.; Healey, M. Place attachment and place identity: First-year undergraduates making the transition from home to university. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, J.; Neal, S. Rural identity and otherness. In The Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 277–281. [Google Scholar]

- Smailes, P.J. From rural dilution to multifunctional countryside: Some pointers to the future from South Australia. Aust. Geogr. 2002, 33, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, S.; Dong, W.; Liu, P.L.; Huang, Z.F.; Wu, B.H.; Lu, S.M.; Xu, F.F.; et al. Memory and homesickness in transition: Evolution mechanism and spatial logic of urban and rural memory. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.Y.; Cheng, Z.F. On the Morality of Nostalgia. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

| N | District | Construction Year | Households Affected | Reason for Resettlement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Huishan | 2002 | About 1900 | Agricultural business |

| B | Beitang | 2007 | About 4000 | Building factories and developing real estate |

| C | Nanchang | 2005 | About 500 | Building a public hospital |

| D | Binhu | 2002 | About 1300 | Building factories and developing real estate |

| E | Xishan | 2011 | About 8000 | Building East New City in Wuxi |

| Steps | ① Initial Coding | ② Focused Coding | ③ Memo-Writing | ④ Axial Coding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Coding key words/phrase in text | Forming subcategories and categories of land attachment | Forming logical link among categories/subcategories | Forming different types of land attachment |

| Operation in NVivo | Making free nodes | Creating tree nodes | Making a document memo | Creating node links in document |

| Dimension | Category | Subcategory | Key Phrases 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dwelling Environment | House | More spacious Better house | More spacious rural house Bigger rooms in rural house More strongly built rural house Preferred decor of rural house More comfortable living in rural house |

| Environment | Close to nature No interference Fewer conflicts | There was quiet life on rural land; good natural environment We lived in villas with no interference from each other We had no conflicts with neighbors, but we do now | |

| Lifestyle | Food security | Healthier food | Did not worry about food safety on my rural land; the cabbages did not have to be sprayed with insecticide; the chickens and ducks tasted better in the countryside |

| Living security | Traffic security Life security Psychological security | There was wide playing space in former times; we did not need to worry about our children’s security We seldom heard that something had been stolen Rural people were peaceful, but now we often come across people with defensive mindsets; rural land supports a peaceful life | |

| Convenience | Convenient for the aged | Senior citizens could better enjoy life on rural land, because they did not have to go up and down stairs as in current life | |

| Convenient for life | It was convenient for me to air my quilt; it was convenient for me to park my car on rural land | ||

| Like farming | Not accustomed to life without rural land | I felt happy when I was planting; I am not accustomed to a life without rural land; undoubtedly, farming made me feel good | |

| Farming is a leisurely lifestyle | Wish to obtain Hobby | I wish to have some land in the country; I would like to plant something; when I was farming, I could live a full life; planting a peach tree could create a hobby for my parents when they are old I could plant flowers as I like; I could plant my beloved flowers | |

| Farming was good for health | Farming was good for health | Farming was good for health; farming was a good way to get exercise. | |

| Freedom | Free lifestyle | I could do as I wished with my goods The lifestyle on rural land made me feel free I loved the lifestyle on rural land | |

| Land Economics | Low living cost | Low cost of living | We could support ourselves on rural land We did not need to buy food |

| Profitable crops | Profitable crops | We had better income by planting cabbages We had better income by planting peach trees | |

| Land Rights | Land rights | No right to choose No participation Can be inherited | We had no choice but to leave our land Our farmer could not participate in policymaking Unlike a city house, a rural house can be inherited by the next generation |

| Land Rootedness | Land rootedness | Memories of ancestors Memories of the living land Memories of the production land Feeling of loss Feeling of familiarity Feeling of pride | I could remember my grandfather and grandmother; rural land was a place where my ancestors lived; the rural land made me miss my ancestors I could remember the games we played in fields and the shining stars on summer nights; it was a tough experience to build a house in those days; my love for the rural land may be a memory. I was good at farm work; I miss the bustling scene of farm work in those days. I feel that the rural land belongs to me; I was reluctant to give up my rural land; I have a feeling of loss; I miss the rural land because it was my birthplace; I took some photos when we left; we cannot live without land; land is the lifeblood of a farmer; I wish my descendants could understand about rural land Only hard-working people like farming; Yangshan’s juicy peaches were the most authentic variety; I was proud to harvest food from the land |

| Land Culture | Land culture | Land worship Land celebration | Some places still maintain the temple of the local god of the land; I participated in the temple fair when I was a child; I can remember the sacrificial ceremony to the local god of the land There was a peach flower festival when spring came |

| Villager Relationships | Get along with villager Help each other | Chat together Felt relaxed No quarrels Help each other | We played together in the country; we chatted with each other and even had meals together; we had many neighbors before, and we chatted after work We did not need to take off our shoes when we visited friends. We did not argue with each other, I felt more relaxed on rural land. I can easily get help from my villagers; even we feel it was common practice to help each other. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, G.; Li, Y.; Hay, I.; Zou, X.; Tu, X.; Wang, B. Beyond Place Attachment: Land Attachment of Resettled Farmers in Jiangsu, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020420

Xu G, Li Y, Hay I, Zou X, Tu X, Wang B. Beyond Place Attachment: Land Attachment of Resettled Farmers in Jiangsu, China. Sustainability. 2019; 11(2):420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020420

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Guoliang, Yi Li, Iain Hay, Xiuqing Zou, Xiaosong Tu, and Baoqiang Wang. 2019. "Beyond Place Attachment: Land Attachment of Resettled Farmers in Jiangsu, China" Sustainability 11, no. 2: 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020420

APA StyleXu, G., Li, Y., Hay, I., Zou, X., Tu, X., & Wang, B. (2019). Beyond Place Attachment: Land Attachment of Resettled Farmers in Jiangsu, China. Sustainability, 11(2), 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020420