Interspecies Sustainability to Ensure Animal Protection: Lessons from the Thoroughbred Racing Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Animals as Resource Repositories and Production Systems

“I no longer shock easily but to this day I remain stunned at what some governments in their legislation and some industries in their policies claim to be ‘sustainable development’. Only in a Humpty Dumpty world of Orwellian doublespeak could the concept be read in the way some would suggest.”([33], p. 167)

1.2. The Thoroughbred Industry in the Interface of Sustainability and Animal Protection

1.3. Overview of Aims, Article Structure, General Conclusions and Purpose of This Study

2. Framing Interspecies Sustainability

2.1. Ecocentrism as a Starting Point

2.2. Themes Emerging from the Discourse in Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems

2.2.1. Species-Innate Functional Integrity

2.2.2. A Holistic Conception of Naturalness

2.2.3. Social Justice and Moral Egalitarianism

2.2.4. Relationality, Agency and Intentionality

2.3. Telos and the Turn toward the Individual

2.4. Ecofeminist Perspectives Foregrounding Animal Agency and Interspecies Relationality

2.5. Summary Interspecies Sustainability

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Scope of This Study

3.2. Informant Recruitment and Response

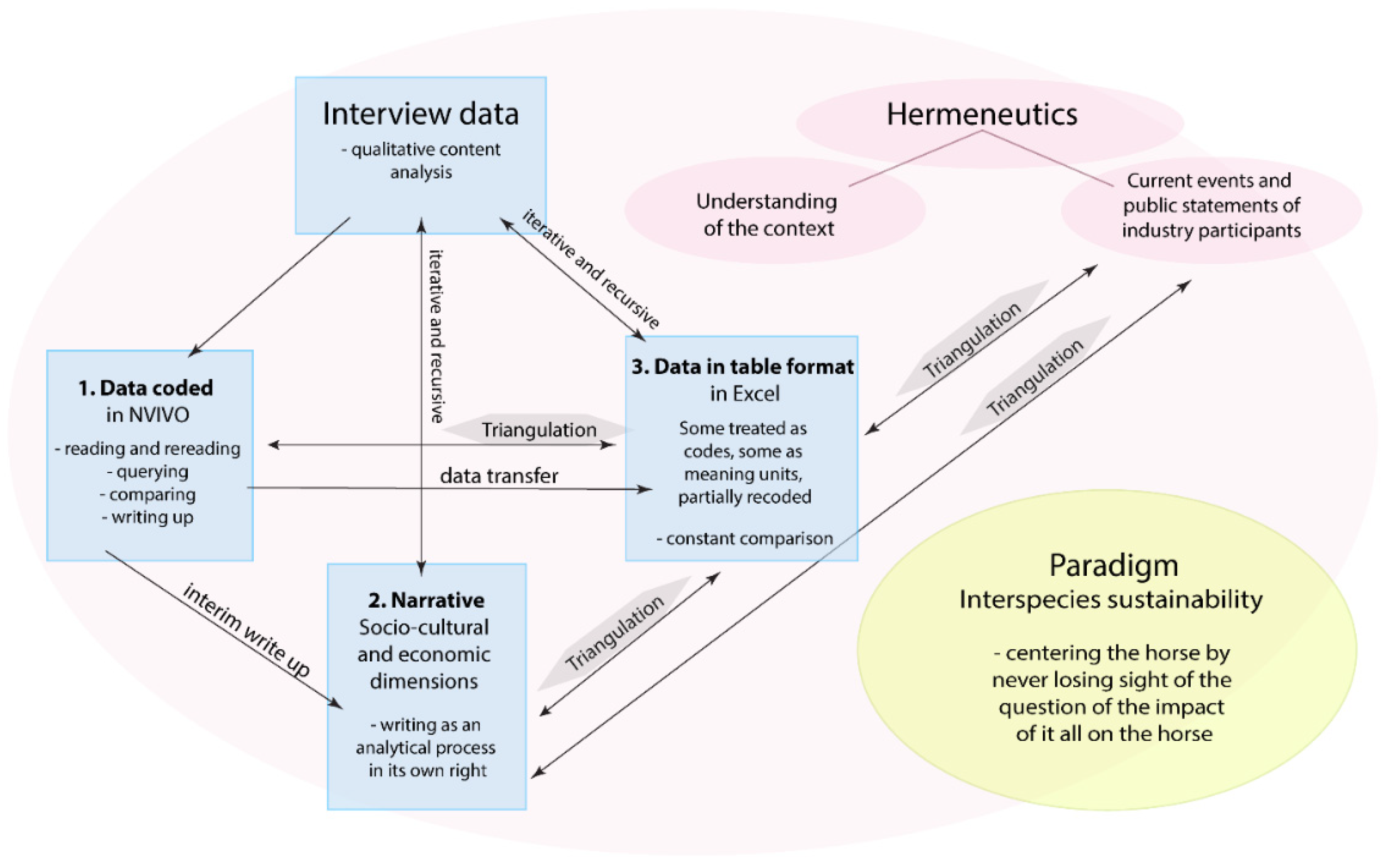

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Industry Informants Defining Sustainability

4.2. Thoroughbred Advocacy Informants’ Discomfort with “Sustainability”

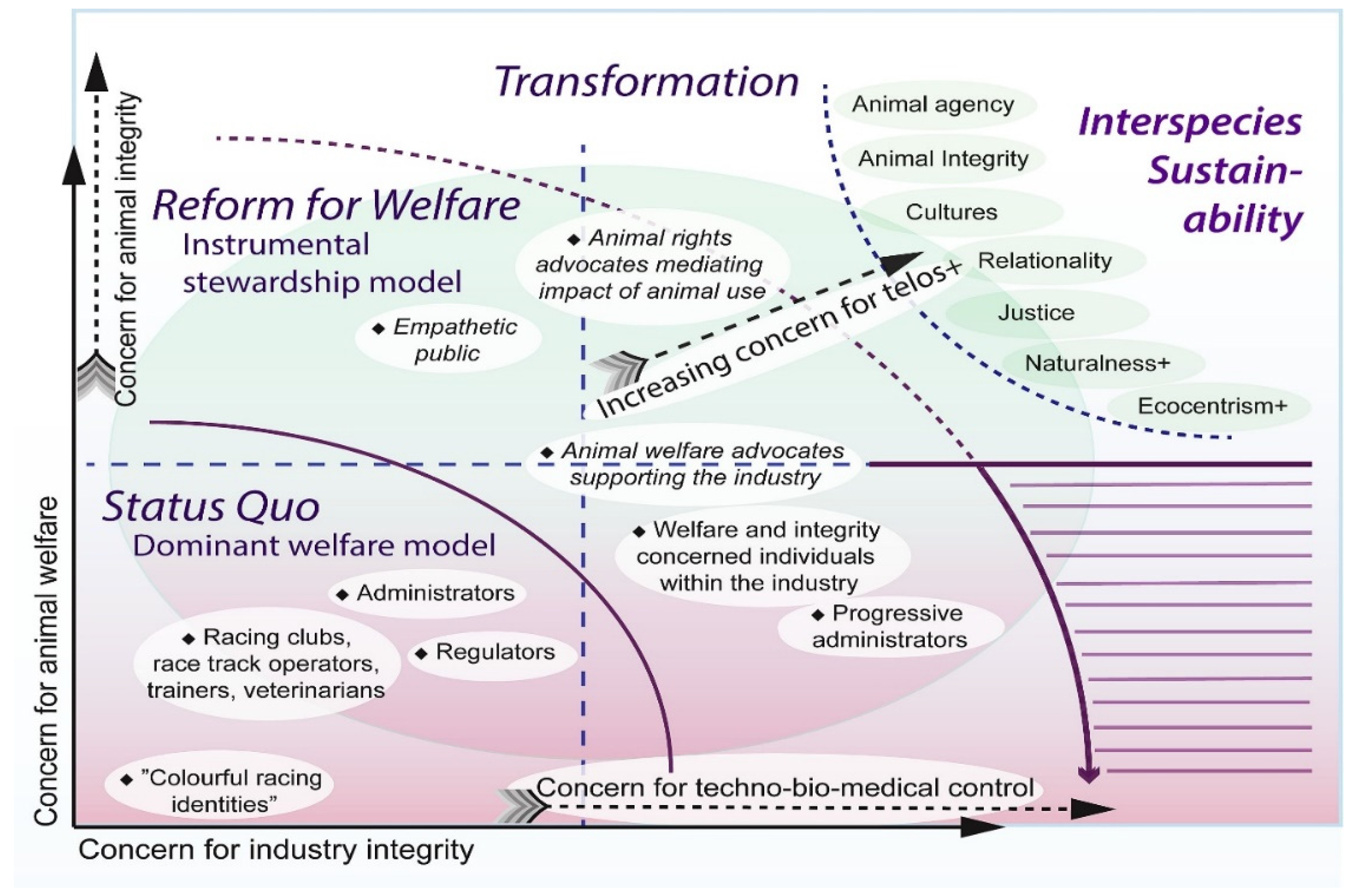

4.3. Situating Thoroughbred Racing in Relation to Interspecies Sustainability

4.3.1. Concern for Industry Integrity and Techno–Bio-Medical Control

“The amount of veterinary technological advances year after year after year is just phenomenal. When I used to go to the races years ago, almost every race meeting a horse would break down which is horrendous… now with the amount of vet work and the amount of what you can do instantly to fix a horse, you know, the surgical advances, the awareness...”

4.3.2. Concern for Animal Welfare and Animal Integrity

4.3.3. Interspecies Sustainability

“some of the handlers were quite rough with [the horses]. You know, they had to be strong and control and dominate them and to me that involved a degree of punishment, using whips and things… At the time, being a student, it didn’t look right to me but then I didn’t question because I didn’t have a particular knowledge about handling horses and horse behaviour. But… I didn’t feel comfortable.”

- R:

- Who do you feel represents the interests of the thoroughbreds in these discussions?

- I1:

- [Sorry?]

- R:

- If you would ask the horse, what would he say who is their advocate?

- I2:

- [laughs slightly].

- I1:

- Hmm.

- I2:

- Good question.

- I1:

- Hmm.

- I2:

- Yeah, I mean, […] the horse’s answer would be the trainer.

- I1:

- Right.

- I2:

- Because that’s where his grain and hay would be coming from. But looking more at the big picture, ehm, I think it would be a [thoroughbred] national organisation like Thoroughbred Charities of America, Thoroughbred Aftercare Alliance or a network of advocate organisations that are thinking about his retirement, planning for his future. But then certainly, ultimately, it’s the owner, because the owner is paying the bills. So I don’t know if there is just one person really.

4.3.4. Identifying Layers of Engagement with Animal Protection

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dobson, A. Environment sustainabilities: An analysis and a typology. Environ. Politics 1996, 5, 401–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, D. The firm and shaky ground of education for sustainable development. In Green Frontiers-Environmental Educators Dancing Away from Mechanism; Transgressions: Cultural Studies and Education; Gray-Donald, J., Selby, D., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, W. Global Ecology and the shadow of “Development”. In Deep Ecology for the Twenty-First Century: Readings on the Philosophy and Practice of the New Environmentalism; Sessions, G., Ed.; Shambhala: Boston, UK, 1995; pp. 428–444. [Google Scholar]

- Washington, H. Demystifying Sustainability: Towards Real Solutions; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Silas, C.J. The environment: Playing to win. Public Relat. J. 1990, 46, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Boscardin, L. Greenwashing the animal-industrial complex: Sustainable intensification and the Livestock Revolution. In Contested Sustainability Discourses in the Agrifood System; Constance, D.H., Konefal, J.T., Hatanaka, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- WCED. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Von Keyserlingk, M.A.G.; Martin, N.P.; Kebreab, E.; Knowlton, K.F.; Grant, R.J.; Stephenson, M.; Sniffen, C.J.; Harner, J.P.; Wright, A.D.; Smith, S.I. Invited review: Sustainability of the US dairy industry. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 5405–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, H.; Gerber, P.; Wassenaar, T.; Castel, V.; Rosales, M.; de Haan, C. Livestock’s Long Shadow; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Westhoek, H.; Lesschen, J.P.; Rood, T.; Wagner, S.; De Marco, A.; Murphy-Bokern, D.; Leip, A.; van Grinsven, H.; Sutton, M.A.; Oenema, O. Food choices, health and environment: Effects of cutting Europe’s meat and dairy intake. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 26, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B.; Beare, D.; Bennett, E.; Hall-Spencer, J.; Ingram, J.; Jaramillo, F.; Ortiz, R.; Ramankutty, N.; Sayer, J.; Shindell, D. Agriculture production as a major driver of the Earth system exceeding planetary boundaries. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnosky, A.D.; Brown, J.H.; Daily, G.C.; Dirzo, R.; Ehrlich, A.H.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Eronen, J.T.; Fortelius, M.; Hadly, E.A.; Leopold, E.B.; et al. Introducing the Scientific Consensus on Maintaining Humanity’s Life Support Systems in the 21st Century: Information for Policy Makers. Anthr. Rev. 2014, 1, 78–109. [Google Scholar]

- Boscardin, L.; Bossert, L. Sustainable Development and Nonhuman Animals: Why Anthropocentric Concepts of Sustainability Are Outdated and Need to Be Extended. In Ethics of Science in the Research for Sustainable Development; Meisch, S., Lundershausen, J., Bossert, L., Rockoff, M., Eds.; Nomos: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 323–352. [Google Scholar]

- IPBES. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kopnina, H. Forsaking Nature? Contesting ‘Biodiversity’ Through Competing Discourses of Sustainability. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 7, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. The victims of unsustainability: A challenge to sustainable development goals. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, T. The meat of the global food crisis. J. Peasant Stud. 2013, 40, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QL (accessed on 19 July 2019).

- Shields, S.; Orme-Evans, G. The Impacts of Climate Change Mitigation Strategies on Animal Welfare. Animals 2015, 5, 361–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadiwel, D.J. The War Against Animals; Critical Animal Studies; Rodopi: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Rawles, K. Sustainable Development and Animal Welfare: The Neglected Dimension. In Animals, Ethics, and Trade: The Challenge of Animal Sentience; Turner, J., D’Silva, J., Eds.; MPG Books Limited: Bodmin, UK, 2006; pp. 208–216. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; Williams, J.; Daily, G.; Noble, A.; Matthews, N.; Gordon, L.; Wetterstrand, H.; DeClerck, F.; Shah, M.; Steduto, P.; et al. Sustainable intensification of agriculture for human prosperity and global sustainability. Ambio 2017, 46, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckers, J. Animal (De)liberation: Should the Consumption of Animal Products Be Banned? Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson, R. From Cattle to Capital: Exchange Value, Animal Commodification, and Barbarism. Crit. Sociol. 2011, 39, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordquist, R.E.; van der Staay, F.J.; van Eerdenburg, F.J.C.M.; Velkers, F.C.; Fijn, L.; Arndt, S.S. Mutilating Procedures, Management Practices, and Housing Conditions That May Affect the Welfare of Farm Animals: Implications for Welfare Research. Animals 2017, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltenacu, P.; Broom, D. The impact of genetic selection for increased milk yield on the welfare of dairy cows. Anim. Welf. 2010, 19, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rauw, W.M.; Kanis, E.; Noordhuizen-Stassen, E.N.; Grommers, F.J. Undesirable side effects of selection for high production efficiency in farm animals: A review. Livest. Prod. Sci. 1998, 56, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, D. Demystifying Dairy. Anim. Stud. J. 2018, 7, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Twine, R. Animals as Biotechnology: Ethics, Sustainability and Critical Animal Studies; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, P.B. Why using genetics to address welfare may not be a good idea. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcari, P. Normalised, human-centric discourses of meat and animals in climate change, sustainability and food security literature. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twine, R. Revealing the “animal-industrial complex”: A concept and method for critical animal studies? J. Crit. Anim. Stud. 2012, 10, 12–39. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeill, J. The forgotten imperative of sustainable development. Environ. Policy Law 2006, 36, 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald, D.A. A Foucauldian Analysis of Environmental Education: Toward the Socioecological Challenge of the Earth Charter. Curric. Inq. 2004, 34, 71–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFHA Members. Available online: https://www.ifhaonline.org/Default.asp?section=About%20IFHA& area=5 (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- McManus, P.; Albrecht, G.; Graham, R. The Global Horseracing Industry: Social, Economic, Environmental and Ethical Perspectives; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, L. Some Touch of Pity; Sid Harta Publishers: Glen Waverly, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, D.; Lamb, M. Driving sustainable growth for Thoroughbred racing and breeding. In Proceedings of the Driving Sustainable Growth for Thoroughbred Racing and Breeding: Findings and Recommendations; Gideon Putnam Resort; The Jockey Club: Saratoga Springs, NY, USA, 14 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The Jockey Club. Vision 2025: To Prosper, Horse Racing Needs Comprehensive Reform; The Jockey Club: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cherwa, J. Horse Racing Industry Fights for Survival in Wake of Deaths and Scrutiny. Los Angeles Times. 2 May 2019. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/sports/more/la-sp-california-horse-racing-survival-20190502-story.html (accessed on 16 July 2019).

- Bergmann, I. He Loves to Race—Or does He? Ethics and Welfare in Racing. In Equine Cultures in Transition: Ethical Questions; Bornemark, J., Andersson, P., Ekström von Essen, U., Eds.; Routledge Advances in Sociology; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, A. Technology and the Contested Meanings of Sustainability; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hector, D.C.; Christensen, C.B.; Petrie, J. Sustainability and Sustainable Development: Philosophical Distinctions and Practical Implications. Environ. Values 2014, 23, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. Whole Systems Thinking as a Basis for Paradigm Change in Education: Explorations in the Context of Sustainability. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bath, Bath, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, R.; Ott, K. The quality of sustainability science: A philosophical perspective. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2011, 7, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, H.; Taylor, B.; Kopnina, H.N.; Cryer, P.; Piccolo, J.J. Why ecocentrism is the key pathway to sustainability. Ecol. Citiz. 2017, 1, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; Alperovitz, G.; Daly, H.; Farley, J.; Franco, C.; Jackson, T.; Kubiszewski, I.; Schor, J.; Victor, P. Building a Sustainable and Desirable Economy-in-Society-in-Nature. In State of the World 2013: Is Sustainability Still Possible? Starke, L., Ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 126–142. [Google Scholar]

- Earth Charter Commission. The Earth Charter; Earth Charter International: San Jose, Costa Rica, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, S.; Demissew, S.; Carabias, J.; Joly, C.; Lonsdale, M.; Ash, N.; Larigauderie, A.; Adhikari, J.R.; Arico, S.; Báldi, A.; et al. The IPBES Conceptual Framework—Connecting nature and people. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelson, G.M. Holistic versus individualistic non-anthropocentrism. Ecol. Citiz. 2019, 2, 137–138. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, P.B. Sustainability as a norm. Techné: Technol. Cult. Concept 1997, 2, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.B.; Nardone, A. Sustainable livestock production: Methodological and ethical challenges. Livest. Prod. Sci. 1999, 61, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.B. The Agrarian Vision: Sustainability and Environmental Ethics; University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, KY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boogaard, B.K.; Oosting, S.J.; Bock, B.B. Defining sustainability as a socio-cultural concept: Citizen panels visiting dairy farms in the Netherlands. Livest. Sci. 2008, 117, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calker, K.J.V.; Berentsen, P.B.M.; Giesen, G.W.J.; Huirne, R.B.M. Identifying and ranking attributes that determine sustainability in Dutch dairy farming. Agric. Hum. Values 2005, 22, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, H.; Roe, E. Commodifying animal welfare. Anim. Welf. 2012, 21, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, H.; Roe, E. Modifying and commodifying farm animal welfare: The economisation of layer chickens. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 33, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; Stewart, G.B.; Panzone, L.A.; Kyriazakis, I.; Frewer, L.J. A Systematic Review of Public Attitudes, Perceptions and Behaviours Towards Production Diseases Associated with Farm Animal Welfare. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2016, 29, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeates, J. Naturalness and Animal Welfare. Animals 2018, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D. Understanding animal welfare. Acta Vet. Scand. 2008, 50, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, G.I. Equity as a Paradigm for Sustainability: Evolving the Process toward Interspecies Equity. Anim. L 1999, 5, 113–146. [Google Scholar]

- Probyn-Rapsey, F.; Donaldson, S.; Iiannides, G.; Lea, T.; Marsh, K.; Neimanis, A.; Potts, A.; Taylor, N.; Twine, R.; Wadiwel, D.; et al. A Sustainable Campus: The Sydney Declaration on Interspecies Sustainability. Anim. Stud. J. 2016, 5, 110–151. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, Y. Where are the Animals in Sustainable Development? Religion and the Case for Ethical Stewardship in Animal Husbandry: Animals in Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnari, M.; Vinnari, E. A Framework for Sustainability Transition: The Case of Plant-Based Diets. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2014, 27, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnari, M.; Vinnari, E.; Kupsala, S. Sustainability Matrix: Interest Groups and Ethical Theories as the Basis of Decision-Making. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2017, 30, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, H.; Blokhuis, H.; Jensen, P.; Keeling, L. Towards Farm Animal Welfare and Sustainability. Animals 2018, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, H.; Morris, C. Beasts of a different burden: Agricultural sustainability and farm animals. In Sustainable Farmland Management: Transdisciplinary Approaches; Fish, R., Seymour, S., Steven, M., Watkins, C., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Harfeld, J.L. Telos and the Ethics of Animal Farming. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2013, 26, 691–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C. ‘Respect for nature’ in the earth charter: The value of species and the value of individuals. Ethicsplace Environ. 2004, 7, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekoff, M. Compassionate Conservation and the Ethics of Species Research and Preservation: Hamsters, Black-Footed Ferrets, and a Response to Rob Irvine. Bioethical Inq. 2013, 10, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudworth, E. Ecofeminism and the animal. In Contemporary Perspectives on Ecofeminism; Phillips, M., Rumens, N., Eds.; Routledge Explorations in Environmental Studies; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Plumwood, V. Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Plumwood, V. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Garlick, S.; Austen, R. Learning about the emotional lives of kangaroos, cognitive justice and environmental sustainability. Relations. Beyond Anthr. 2014, 2, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, A. Sentientist Politics: A Theory of Global Inter-Species Justice; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, S.; Kymlicka, W. Zoopolis: A Political Theory of Animal Rights; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.; Curry, P. Ecodemocracy: Helping wildlife’s right to survive. ECOS 2016, 37, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- IFHA. International Agreement on Breeding, Racing and Wagering; International Federation of Horseracing Authorities: Boulogne, France, 2019; Available online: https://ifhaonline.org/default.asp?section=IABRW &area=15 (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- IFHA. Boulogne, France. Available online: http://www.ifhaonline.org/ (accessed on 16 July 2019).

- Butler, D.; Valenchon, M.; Annan, R.; Whay, H.; Mullan, S. Living the ‘Best Life’ or ‘One Size Fits All’—Stakeholder Perceptions of Racehorse Welfare. Animals 2019, 9, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.; Valenchon, M.; Annan, R.; Whay, H.R.; Mullan, S. Stakeholder Perceptions of the Challenges to Racehorse Welfare. Animals 2019, 9, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birke, L. “Learning to Speak Horse”: The Culture of “Natural Horsemanship”. Soc. Anim. 2007, 15, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, P. Power, ethics and animal rights. In Equine Cultures in Transition: Ethical Questions; Bornemark, J., Andersson, P., Ekström von Essen, U., Eds.; Routledge Advances in Sociology; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nurs. Open 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P.; Hayek, A.; Jones, B.; Evans, D.; McGreevy, P. Number, causes and destinations of horses leaving the Australian Thoroughbred and Standardbred racing industries. Aust. Vet. J. 2014, 92, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.; McManus, P. Changing Human-Animal Relationships in Sport: An Analysis of the UK and Australian Horse Racing Whips Debates. Animals 2016, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvester, J. Do Crooks Fancy Horse Racing? You Can Bet on it! The Age. 18 August 2012. Available online: https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/do-crooks-fancy-horse-racing-you-can-bet-on-it-20120817-24dym.html (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- AAEP. Clinical Guidelines for Veterinarians Practicing in a Pari-Mutuel Environment; American Association of Equine Practitioners: Lexington, KY, USA, 2010; Available online: https://aaep.org/newsroom/whitepapers (accessed on 25 September 2019).

- RCVS Berkshire Equine Vet Struck off for Dishonesty and Breaching Racing Rules. Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. Professionals. 23 February 2011. Available online: https://www.rcvs.org.uk/news-and-views/news/berkshire-equine-vet-struck-off-for-dishonesty-and-breaching-rac/ (accessed on 27 September 2019).

- Anon. Danny O’Brien and Mark Kavanagh Cleared of Administering Cobalt by Court of Appeal. The Sydney Morning Herald. 17 November 2017. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/sport/racing/victorian-trainers-partly-win-appeal-on-cobalt-charges-20171117-gzn887.html (accessed on 27 September 2019).

- Crispe, E.J.; Lester, G.D. Exercise-induced Pulmonary Hemorrhage: Is It Important and Can It Be Prevented? Vet. Clin. Equine Pract. 2019, 35, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D. Lasix: The Drug Debate Which is Bleeding US Horse Racing Dry. The Guardian. 31 August 2014. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/sport/2014/aug/31/lasix-drug-debate-bleeding-horse-racing (accessed on 28 July 2015).

- AAEP. Position on Therapeutic Medications in Racehorses. Available online: https://aaep.org/position-therapeutic-medications-racehorses (accessed on 23 September 2019).

- Meyer, H. Divergierende Interessen und Konflikte beim tierärztlichen Einsatz für die sportliche Leistungsfähigkeit des Pferdes einerseits und für dessen langfristiges Wohlergehen andererseits. Pferdeheilkunde (Equine Med.) 2009, 25, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blea, J.A. Ethical issues for the racetrack practitioner. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Convention of the American Association of Equine Practitioners—AAEP, Anaheim, CA, USA, 1–5 December 2012; American Association of Equine Practitioners: Lexington, KY, USA, 2012; Volume 58. [Google Scholar]

- Water Hay Oats Alliance. Available online: http://www.waterhayoatsalliance.com/ (accessed on 26 September 2019).

- Haynes, R.P. Competing Conceptions of Animal Welfare and Their Ethical Implications for the Treatment of Non-Human Animals. Acta Biotheor. 2011, 59, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futureye. Commodity or Sentient Being-Australia’s Shifting Mindset on Farm Animal Welfare; Futureye: Windsor, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Faunalytics Animal Tracker 2019: Methods & Overview. Available online: https://faunalytics.org/animal-tracker-2019-methods-overview/ (accessed on 16 July 2019).

- Duncan, E.; Graham, R.; McManus, P. ‘No one has even seen… smelt… or sensed a social licence’: Animal geographies and social licence to operate. Geoforum 2018, 96, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P. Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Francione, G.L. Reflections on “Animals, Property, and the Law” and “Rain without Thunder”. Law Contemp. Probl. 2007, 70, 9–57. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, C.; Young, W. Fatalities and Fascinators: A New Perspective on Thoroughbred Racing. In Domestic Animals and Leisure; Carr, N., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2015; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Australasian Animal Studies Association Decolonizing Animals—Book of Abstracts. In Proceedings of the Decolonizing Animals 2019 Conference, Hosted by the New Zealand Centre for Human-Animal Studies/Te Puna Akoranga o Aotearoa mō te Tangata me te Kararehe. The Piano, Ōtautahi (Christchurch), New Zealand, 1–4 July 2019; Available online: https://aasa2019.org/ (accessed on 16 July 2019).

- Horseman, S.V.; Buller, H.; Mullan, S.; Knowles, T.G.; Barr, A.R.S.; Whay, H.R. Equine Welfare in England and Wales: Exploration of Stakeholders’ Understanding. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2017, 20, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, K. Animals, Work, and the Promise of Interspecies Solidarity; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bauhardt, C. Solutions to the crisis? The Green New Deal, Degrowth, and the Solidarity Economy: Alternatives to the capitalist growth economy from an ecofeminist economics perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 102, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornemark, J.; Andersson, P.; Ekström von Essen, U. Equine Cultures in Transition: Ethical Questions. In Routledge Advances in Sociology, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

| Interspecies Sustainability | Anthropocentric Sustainability |

|---|---|

| Animals as autonomous beings with a sense of self, purpose and needs based on their telos. | Animals as a repository, as bioreactor and production system for the benefit of humans. |

| Freedom to exercise agency. | Restriction and control. |

| Animals as embodied subjects of inter-and intra-species communities. | Animals seen as disconnected. |

| Animals with their own species-specific cultures and knowledge systems. | Animals as square pegs to be fitted into round holes for human purposes. |

| Respecting individual differences (of animals of the same species) in physiology, behaviour and appearance. | Optimisation of body and mind as needed for human purposes. |

| Respecting species-innate functional integrity and natural (and individual) limits. | Biotechnical manipulation to exceed natural limits, also at the expense of welfare. |

| Supporting those with individual differences and facilitating their participation in a fulfilling life. | Suppression and extermination of individual differences. |

| Acknowledging similarities between human and other animals. | Emphasising what distinguishes humans from other animals to justify a hierarchical order. |

| Respecting that nonhumans covet life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness just as humans do. | Machine-like artifact to be controlled; Animals as non-sentient, or at best animals as primarily suffering beings. |

| Animal protection to apply to animal cultures, autonomy, self-determination, sense of control, fulfilling telos and the ability to create and maintain meaningful relationships. | In theory: Welfare rather than protection focusing on basic health and functioning, also recently on affective states, some considering natural living. |

| Recognising interdependence and reciprocity between animals, humans and the natural world. | Strict boundaries to separate humans from other animals and nature, human exceptionalism. |

| Precautionary principle (being mindful of limited knowledge of animal capacities). | Rejecting or minimising the potential for any breadth and depth of animal capacities. |

| Compassionate conservation, recognising the need to protect the individual from harm. | Conservation, focusing on species protection at the expense of individual animals and for the benefit of humans. |

| Nature and animals forming a self-sustaining and self-organising system. | Nature and animals as something to be managed. |

| Inherent worth of all species and nature including the abiotic components. | Instrumental view of all species and nature for human benefit. |

| Focus on present and future generations of all species and ecosystems, including their abiotic components. | Consideration of the nonhuman only in so far as they serve current and future generations human needs and wants. |

| Naturalness as inherent worth to be preserved. | Nature as “limiting factor” on human progress, preferencing technological and biomedical alteration. |

| Humanity regards itself as being immanent within an ecological system. | Human detachment and separation from animals and nature, nature/reason dualism. |

| Honouring qualities such as harmony, balance, reverence, sacredness and spirituality. | Belief in mastery, reduction to scientism, the rational, quantifiable, measurable. |

| Interspecies Sustainability | Anthropocentric Sustainability |

|---|---|

| Interspecies equity based. | Hierarchical. |

| Relations and partnership based, reciprocal. | Domination by humans. |

| Respecting otherness. | Using otherness to justify devaluing the other. |

| Interdependence. | Separation. |

| Respecting boundaries of privacy and “letting them live their lives”. | Ongoing intrusion and invasion. |

| Nonhumans and humans as embedded in networks of socio-ecological relationships that matter to them. | Alienation and separation or negation of animal to animal, and animal to human relationships. |

| Species inclusive ongoing dialogue and co-evolutionary. | Prescribed by hegemonic forces and technological means. |

| Ongoing re-defining, with animals sharing the re-defining equally. | Human control with strict boundaries. |

| Mutually and culturally defined. | Technocratically and economically defined. |

| Interspecies Sustainability | Anthropocentric Sustainability |

|---|---|

| Flourishing of telos including animal agency, animal cultures, naturalness, dignity, identity, subjectivity, autonomy, species-innate functional integrity. | Animal and nature a renewable resource and a manipulable repository for human benefit. |

| Nonhuman and human co-creating realities and relational flourishing. | Separation from animals and nature. |

| Interspecies justice. | Intergenerational (human) justice. |

| Inherent value of animals and nature (including abiotic elements). | Consideration of the nonhuman only in so far as they serve current and future generations human needs and wants. |

| Obligations to nonhumans and ecosystems. | Obligations predominantly to human welfare, inadvertently overlooking or deliberately rejecting the interests of other than human interests. |

| Eschews the substitutability debate. | Based on varying degrees of substitutability. |

| Species equity, no special moral status of humans. | Human exceptionalism. |

| Largely based in preservationism—to protect, preserve and restore natural systems. | Largely based in conservationism (“wise use” to benefit humans). |

| Emphasis on culture (i.e., guided by questioning what is it that truly sustains us?). | Technocentrism, technocratic approach with emphasis on the economy and materialism. |

| Systems perspective, ecological system oriented. | Reductionism, linearity. |

| Transparency: values to be recognised and made transparent, discourse about values for decision-making. | Values undisclosed, or purportedly values free. |

| Decolonising animal knowledge systems, indigenous knowledge systems, and local knowledge; leading to co-production of knowledge; Transdisciplinarity. | Specialist expert knowledge oriented; fragmented knowledge silos. |

| Growth critique; zero growth/de-growth. | Adherence to the growth paradigm, mistaking growth with progress. |

| US | AUS | UK | Int’l | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thoroughbred Industry Informant | 5 | 3 | - | 1 | 9 |

| Animal Advocacy Informant | 2 | 3 | 2 | - | 7 |

| Total | 7 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 16 |

| Animal Protection Status | Layers | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Status quo/Dominant Welfare Model | Layer 1 | Animal protection is focused on functioning for optimal race day performance. |

| Layer 2 | Animal protection is a by-product of measures taken for industry integrity. | |

| Reform for Welfare/Instrumental Stewardship Model | Layer 3 | Animal protection is considered to be equal in importance to racing integrity measures but the focus is on the most egregious welfare violations. |

| Layer 4 | Under Layer 4, the industry prioritises increased techno–bio-medical manipulation and control and presents these advances as evidence for their caring for welfare. The agricultural sector uses this process to meet the sustainability criterion of efficiency and the economic criterion of optimisation. | |

| Layer 5 | Layer 5 moves animal protection beyond ameliorating death and injuries and the most egregious welfare violations to consider the entire range of issues of the day-to-day living conditions, environmental conditions and, to a limited degree, human–animal interactions. It is, ideally and with good intentions, about a species-relevant and fulfilled life for the animal’s entire lifespan. | |

| Layer 6 | This layer is situated within the framework of animal welfare science. For this layer to have any legitimacy, the decisions of which welfare criteria are favoured and the values applied to make that decision need to be transparent. | |

| Transformation/Interspecies Sustainability | Layer 7 | Layer 7 engages with all aspects of interspecies sustainability ranging from telos, animal autonomy, individuality, interspecies relationships, interspecies justice, species-innate functional integrity, animal knowledge systems, animal cultures, naturalness+, to animals as co-creators of a multispecies world. Industry informants have not demonstrated relevant understanding of these aspects. Some advocacy informants refer to some aspects but have not integrated this intuitive understanding with advocacy strategies and goals. |

| Layer 8 | Layer 8 is constituted of the social, cultural and political realms and strategies. It is situated to tackle the root causes of animal exploitation and needs to be leveraged to create the conditions for interspecies sustainability. It requires a shift of power, inter alia through representation and participation of the animal in governance, administration, regulatory institutions and the judiciary. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bergmann, I.M. Interspecies Sustainability to Ensure Animal Protection: Lessons from the Thoroughbred Racing Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195539

Bergmann IM. Interspecies Sustainability to Ensure Animal Protection: Lessons from the Thoroughbred Racing Industry. Sustainability. 2019; 11(19):5539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195539

Chicago/Turabian StyleBergmann, Iris M. 2019. "Interspecies Sustainability to Ensure Animal Protection: Lessons from the Thoroughbred Racing Industry" Sustainability 11, no. 19: 5539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195539

APA StyleBergmann, I. M. (2019). Interspecies Sustainability to Ensure Animal Protection: Lessons from the Thoroughbred Racing Industry. Sustainability, 11(19), 5539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195539