Sustainable Business Models through the Lens of Organizational Design: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Sustainable Business Models

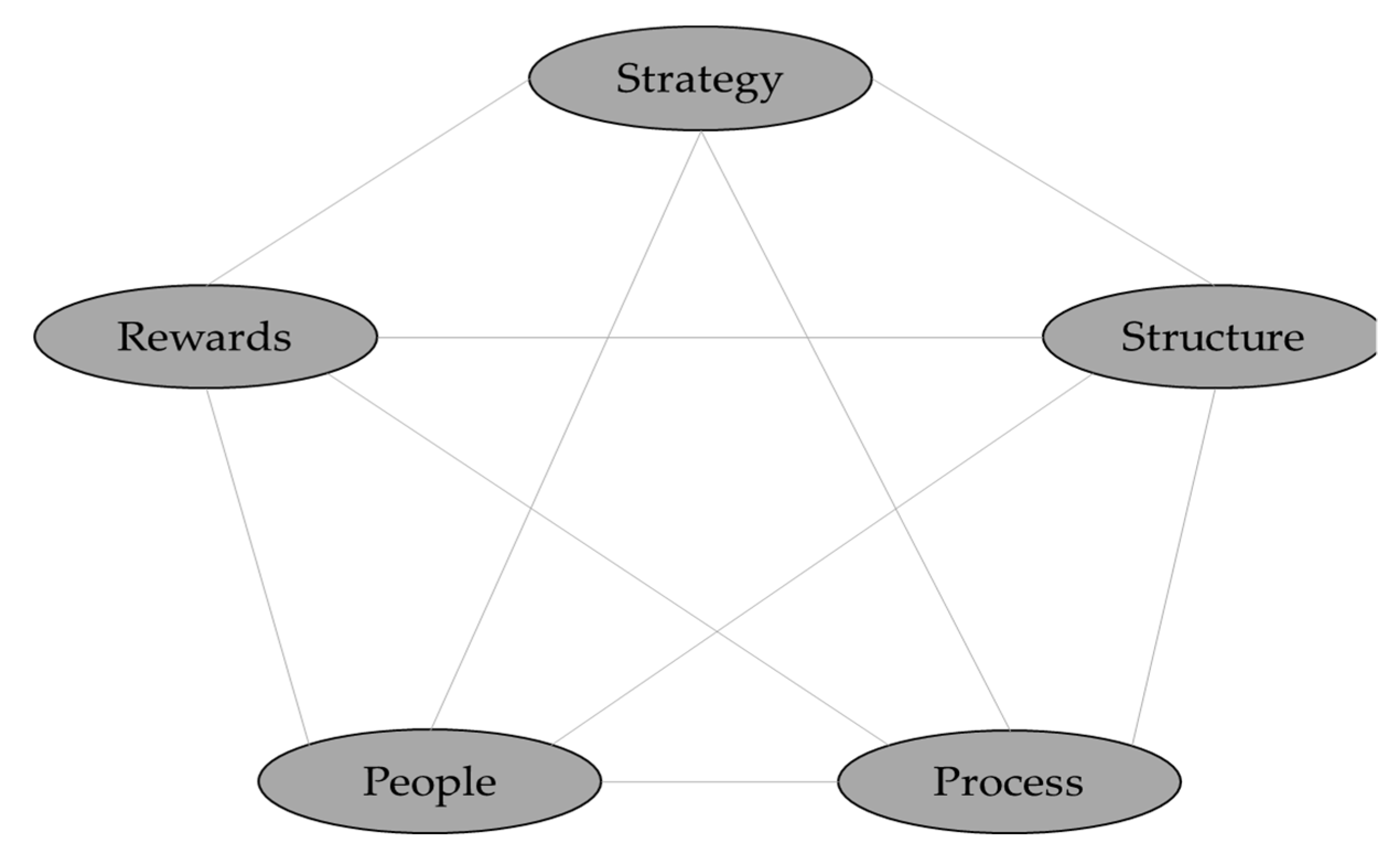

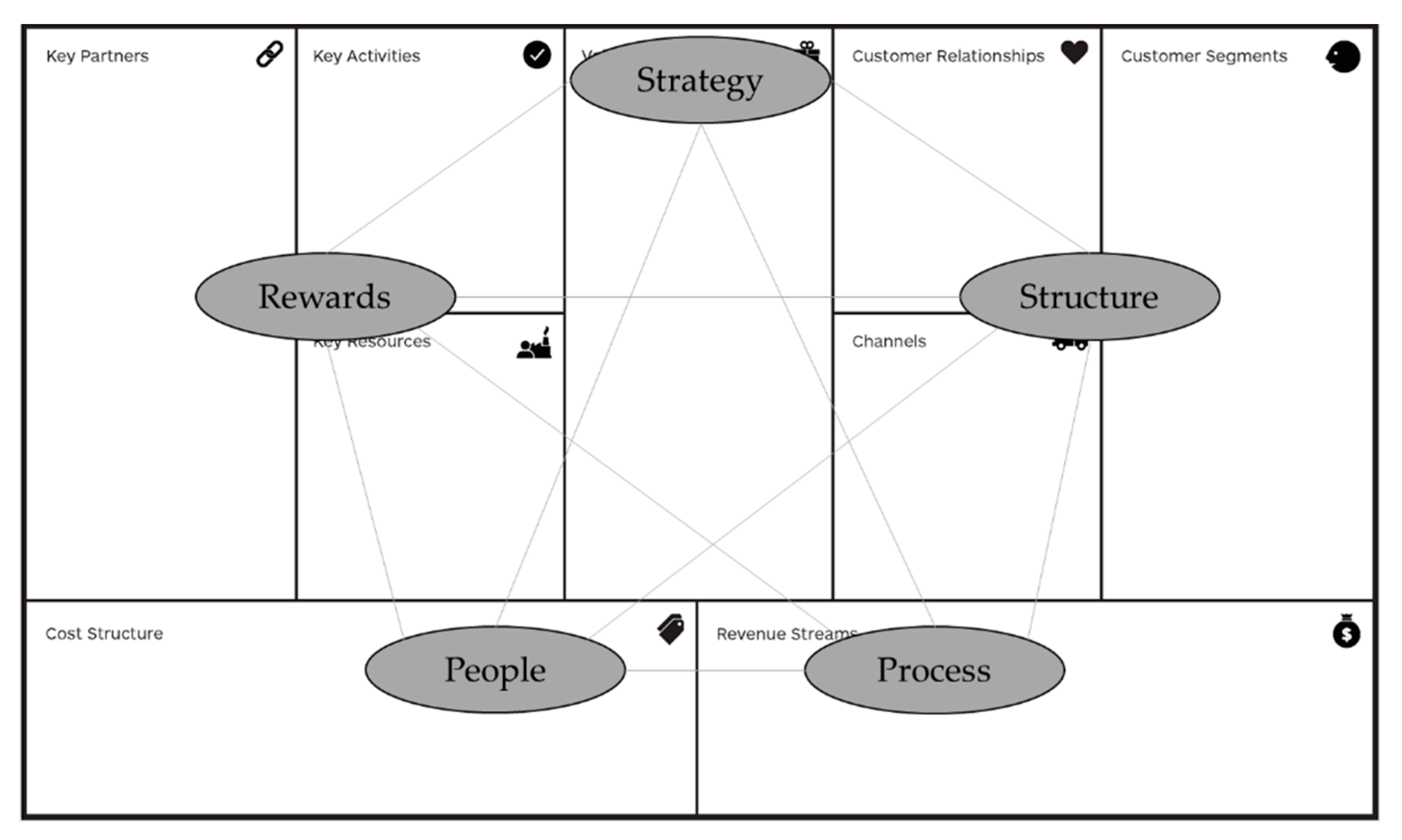

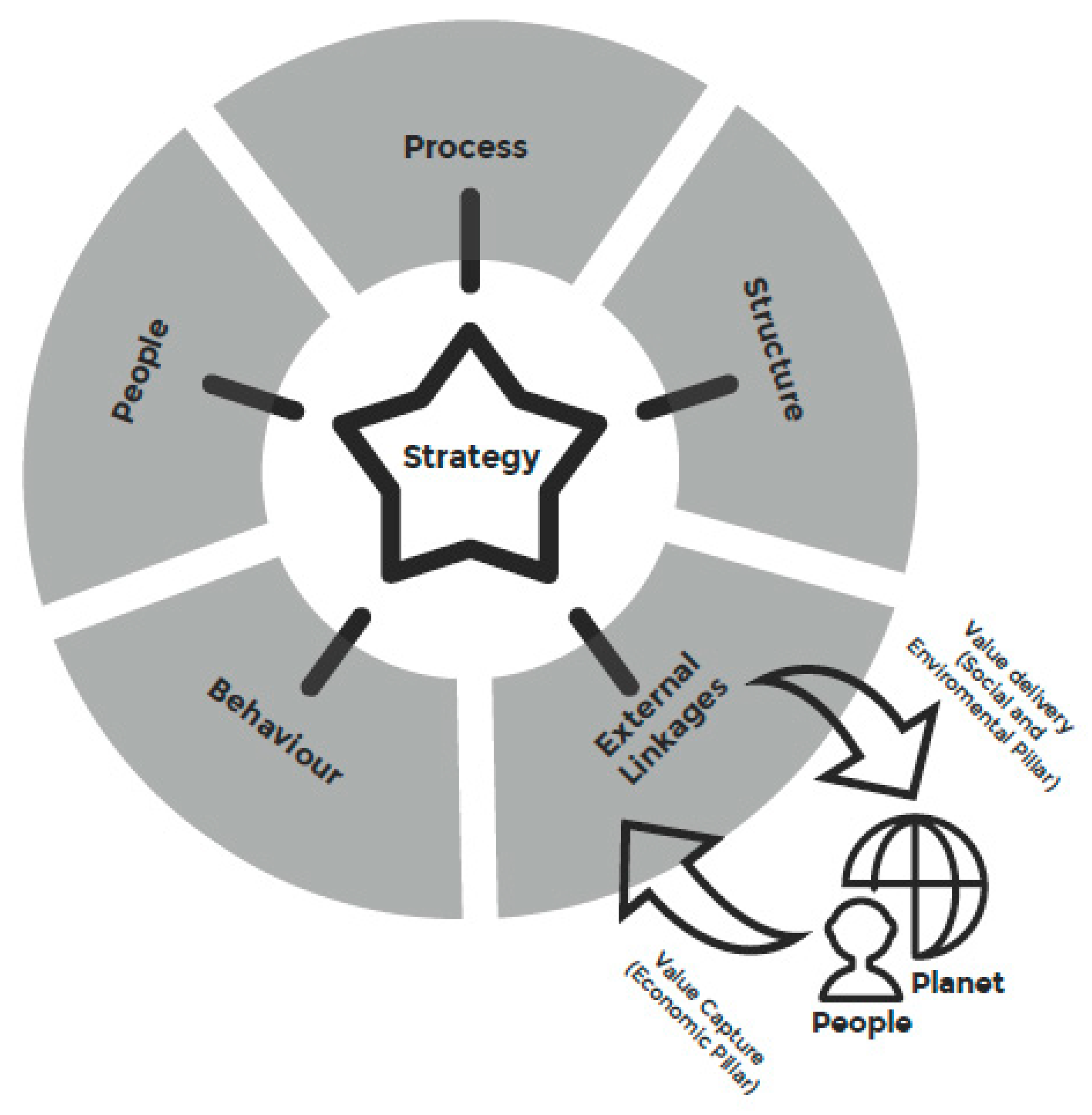

2.2. Organizational Design

2.3. Linking Sustainable Business Models and Organizational Design

2.4. Research Question

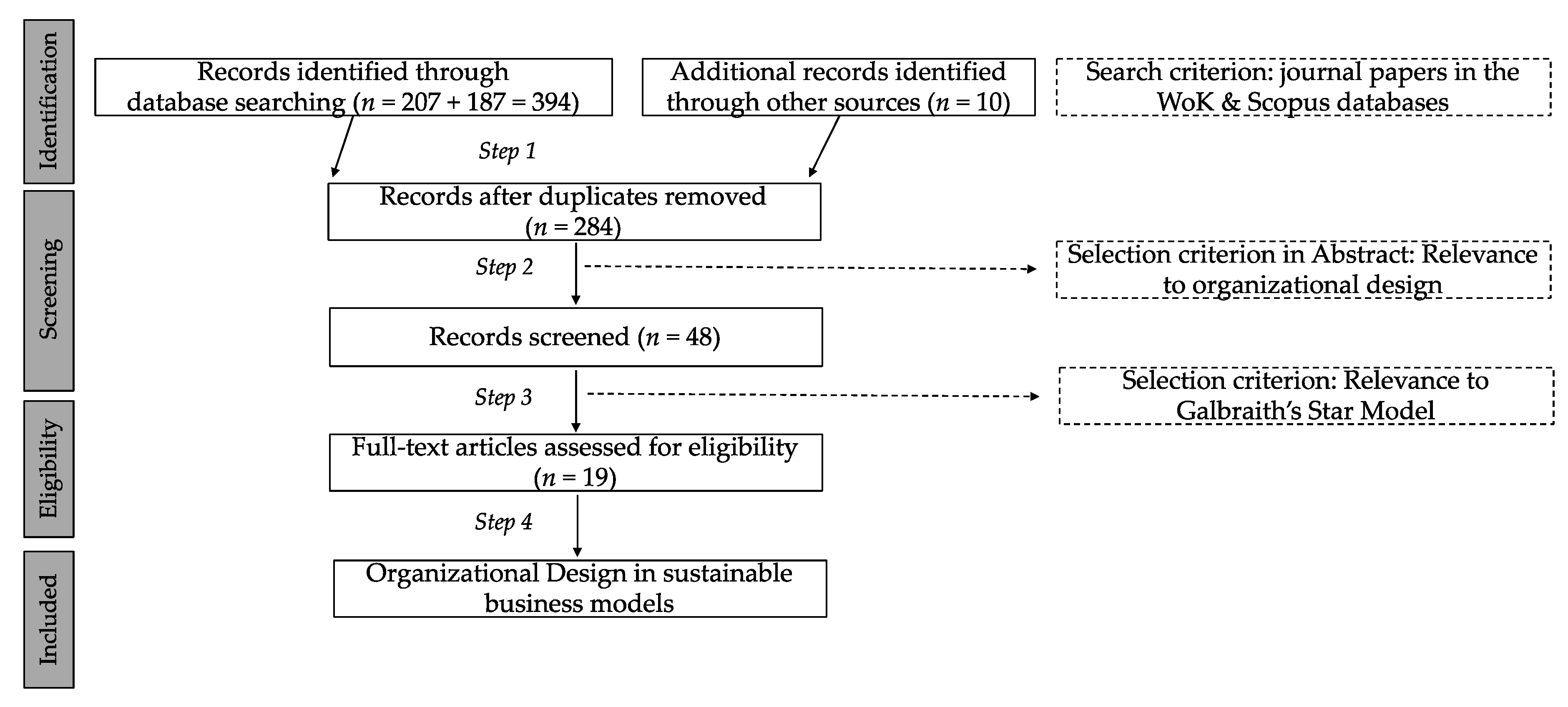

3. Research Methodology

4. Results

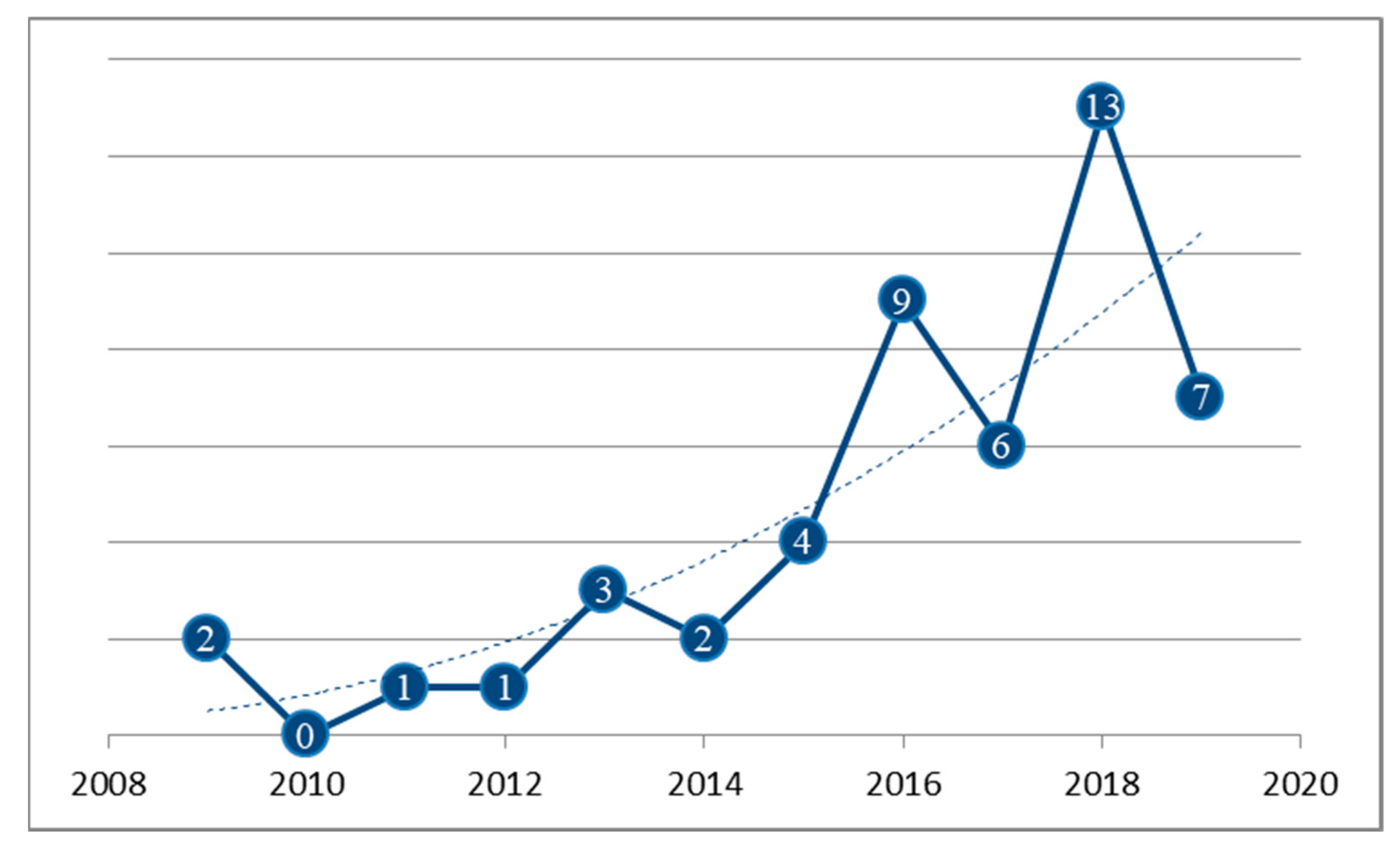

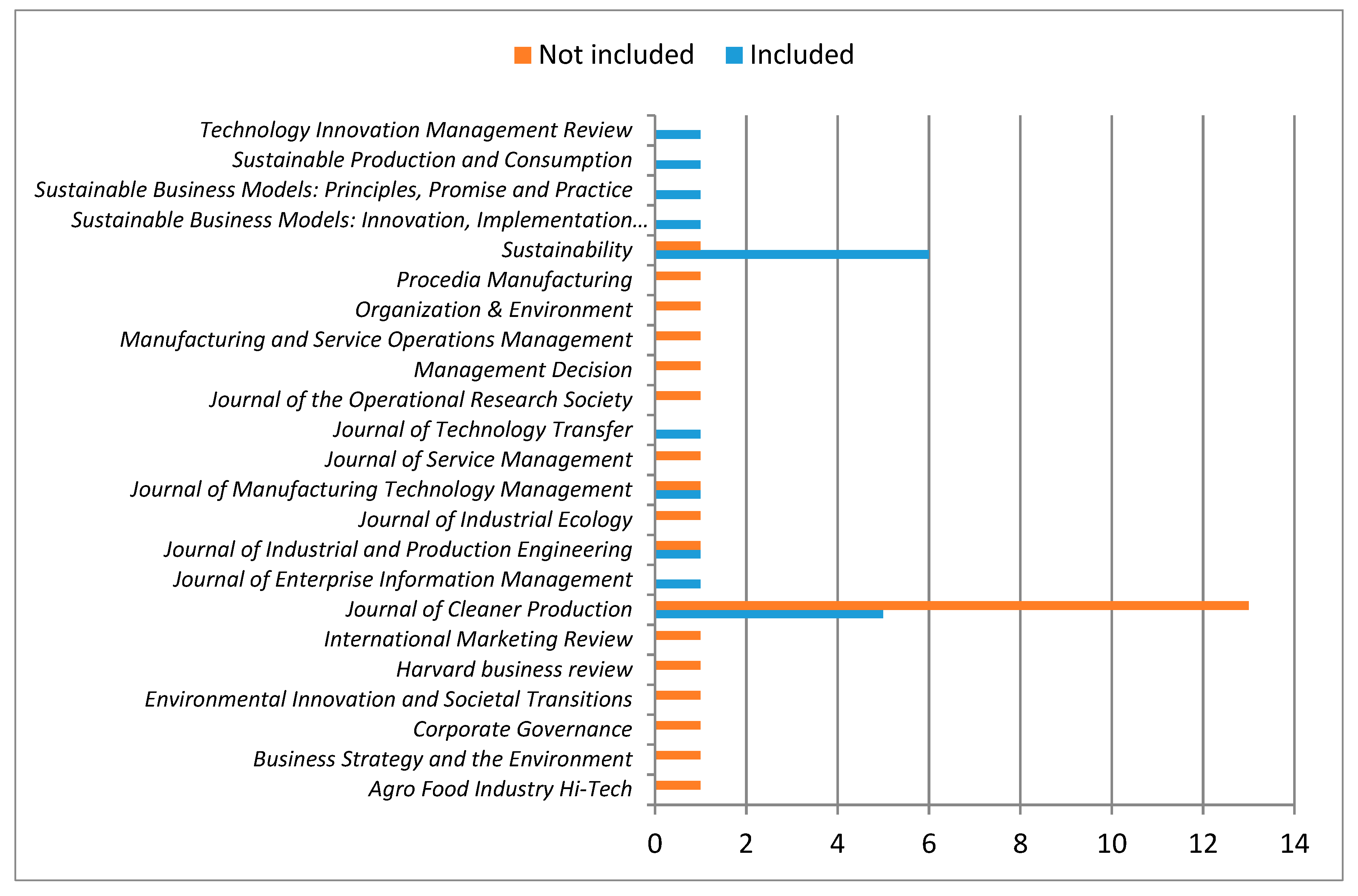

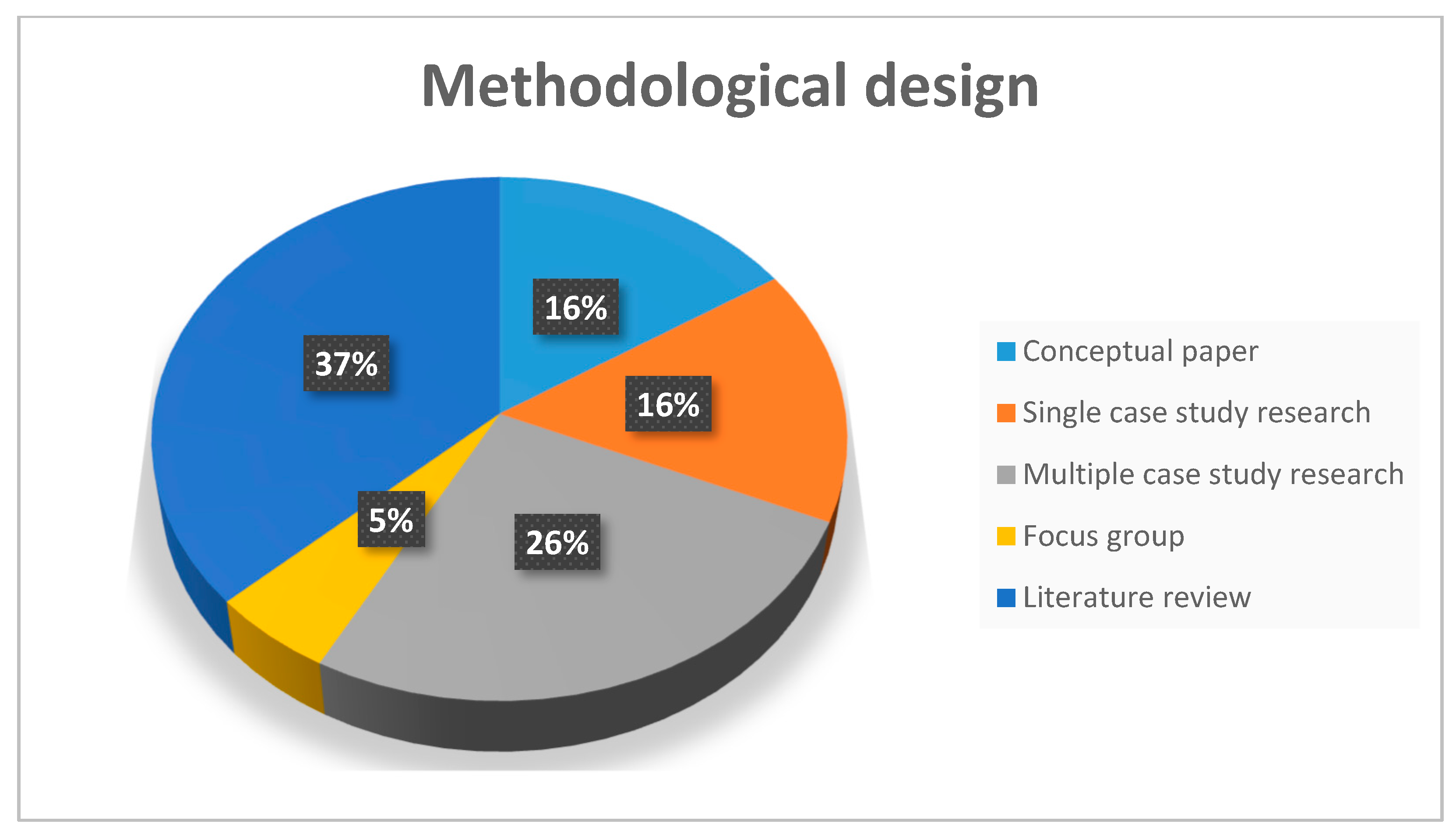

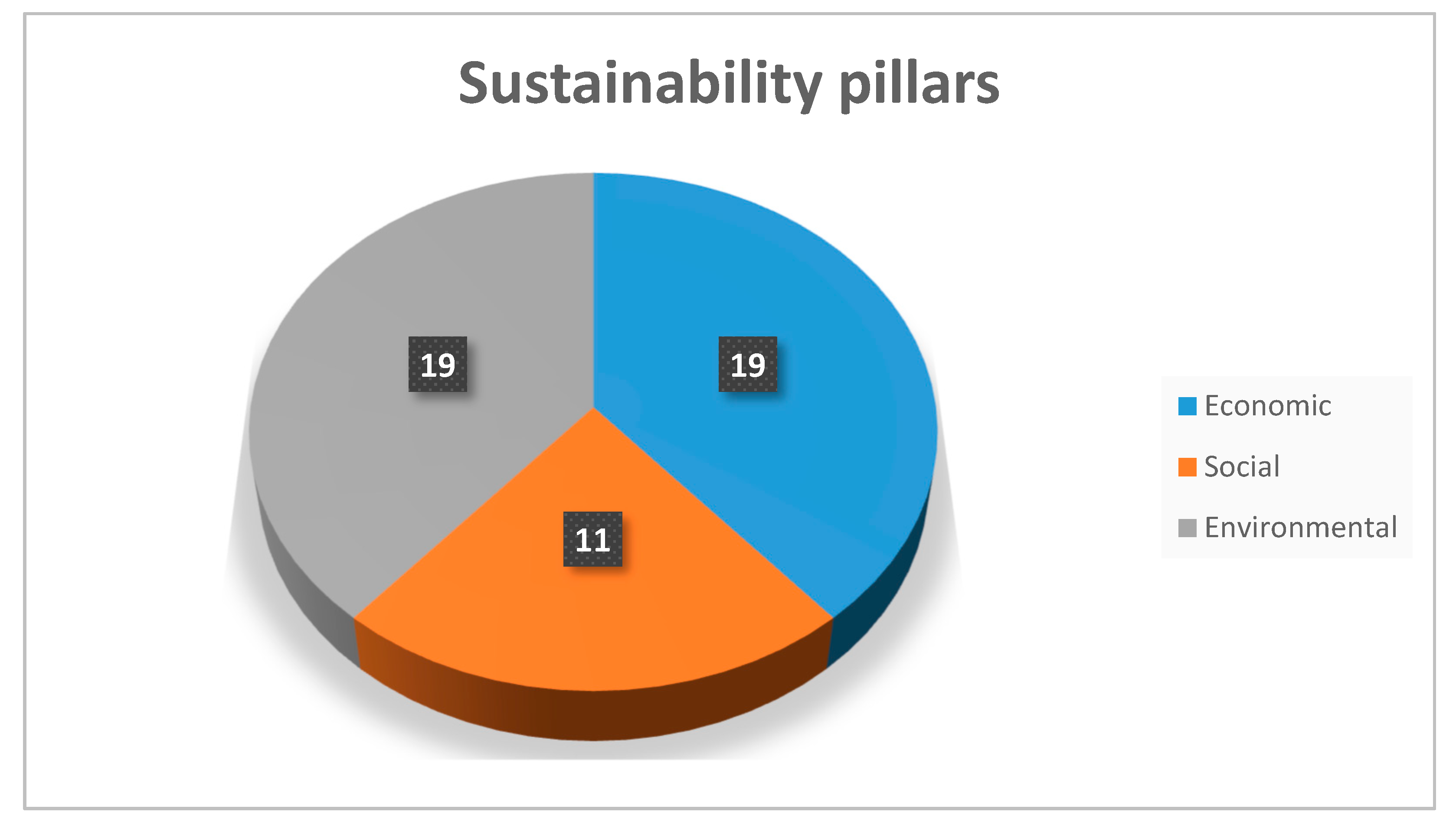

4.1. Descriptive Findings

4.2. Organizational Design Approach

4.2.1. Strategy

4.2.2. Structure

4.2.3. Process

4.2.4. People

4.2.5. Rewards

5. Discussion

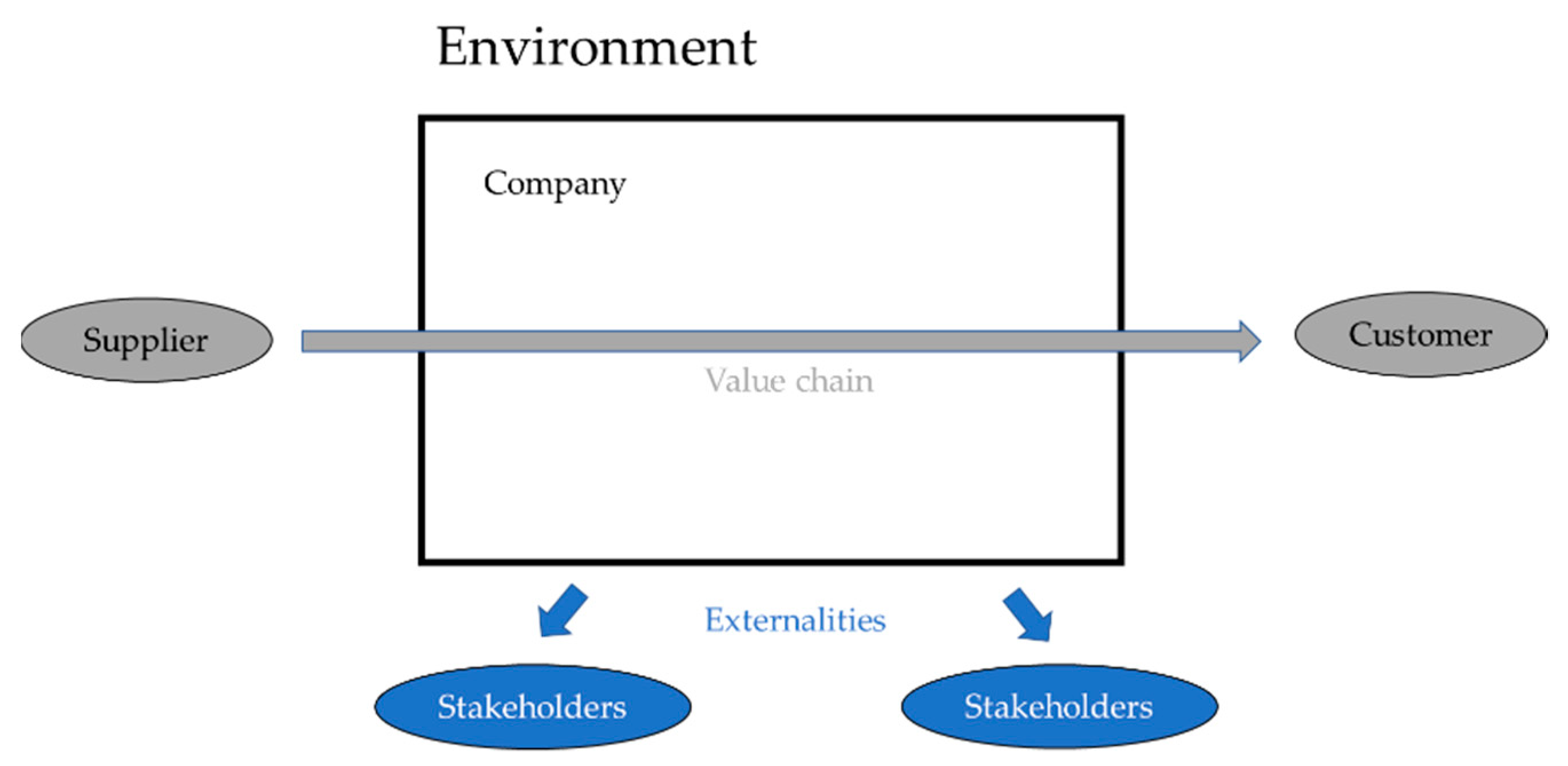

5.1. The Extension of the Organizational Boundaries for Design Elements

5.2. The Lack of Studies Related to the Rewards Organizational Element

5.3. The Implications of Organizational Design for Strategy Implementation of Sustainable Business Models

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Avenues for Further Research

- First, there is a need to extend the organizational design elements beyond the borders of a firm. Most studies recognize the need for collaboration when it comes to sustainable business models. The integration of value networks is of the utmost importance and requires the identification of inter-organizational and societal design elements.

- Second, there is a lack of studies related to the Rewards organizational element discussing aspects such as incentive systems and human-behavior constructs.

- Third, a common feature of the final selected articles is that they all provide examples of the strategy implementation related to a change in strategy that originated a new business model focused on sustainability. Consequently, we consider that this strategy execution is possible thanks to the configuration of an organizational design that is aligned to the business model. This could indicate that as business models are useful to explain the business logic at the strategic level, organization might be a useful lens to explain the business logic at a tactical level that enables the implementation of the desired strategy.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Reference | Conceptual Paper | Single Case Study Research | Multiple Case Study | Focus Groups | Literature Review |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borland (2009) [47] | X | ||||

| Nidumolu et al. (2009) [62] | X | ||||

| Duran-Encalada and Paucar-Caceres (2012) [48] | X | ||||

| Girotra and Netessine (2013) [49] | X | ||||

| Zollo et al. (2013) [50] | X | ||||

| Bocken, Short, Rana, Evans (2014) [14] | X | ||||

| Bocken, Rana, Short (2015) [44] | X | ||||

| Reim et al. (2015) [51] | X | ||||

| Antikainen and Valkokari (2016) [52] | X | ||||

| Bocken, Short (2016) [54] | X | ||||

| Bocken, de Pauw, Bakker, van der Grinten (2016) [53] | X | ||||

| Geissdoerfer, Bocken, Hultink (2016) [55] | X | ||||

| Jablonski (2016) [57] | X | ||||

| Jablonski and Jablonski (2016) [56] | X | ||||

| Joyce and Paquin (2016) [58] | X | ||||

| Lewandowski (2016) [59] | X | ||||

| Moreno et al. (2016) [60] | X | ||||

| Geissdoerfer; Vladimirova; Evans (2018) [10] | X | ||||

| Ünal, Urbinati, Chiaroni, (2019) [17] | X |

| Reference | Environmental | Social | Economic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Borland (2009) [47] | X | X | |

| Nidumolu et al. (2009) [62] | X | X | |

| Duran-Encalada and Paucar-Caceres (2012) [48] | X | X | X |

| Girotra and Netessine (2013) [49] | X | X | |

| Zollo et al. (2013) [50] | X | X | X |

| Bocken, Short, Rana, Evans (2014) [14] | X | X | X |

| Bocken, Rana, Short (2015) [44] | X | X | X |

| Reim et al. (2015) [51] | X | X | |

| Antikainen and Valkokari (2016) [52] | X | X | |

| Bocken, Short (2016) [54] | X | X | X |

| Bocken, de Pauw, Bakker, van der Grinten (2016) [53] | X | X | |

| Geissdoerfer, Bocken, Hultink (2016) [55] | X | X | X |

| Jablonski (2016) [57] | X | X | X |

| Jablonski and Jablonski (2016) [56] | X | X | X |

| Joyce and Paquin (2016) [58] | X | X | X |

| Lewandowski (2016) [59] | X | X | |

| Moreno et al. (2016) [60] | X | X | |

| Geissdoerfer; Vladimirova; Evans (2018) [10] | X | X | X |

| Ünal, Urbinati, Chiaroni, (2019) [17] | X | X |

References

- Mohrman, S.A.; Worley, C.G. The organizational sustainability journey: Introduction to the special issue. Organ. Dyn. 2010, 39, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of Twenty-First Century Business; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Ricart, J.E. From strategy to business models and onto tactics. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P. The Practice of Management; Heinemman: London, UK, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J.; Saebi, T. Fifteen Years of Research on Business Model Innovation: How Far Have We Come, and Where Should We Go? J. Manag. 2017, 43, 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbari, M.; Morales-Alonso, G.; Carrasco-Gallego, R. Conceptualizing the sharing economy through presenting a comprehensive framework. Sustainaibility 2018, 10, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, E.; Urbinati, A.; Chiaroni, D.; Manzini, R. Value Creation in Circular Business Models: The case of a US small medium enterprise in the building sector. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Evans, S. Sustainable business model innovation: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, H.; Fischer, T.; Fleisch, E. Exploring the interrelationship among patterns of service strategy changes and organizational design elements. J. Serv. Manag. 2010, 21, 103–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeldstad, Ø.D.; Snow, C.C. Business models and organization design. Long Range Plann. 2018, 51, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Hansen, E.G.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business Models for Sustainability: Origins, Present Research, and Future Avenues. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaosman, H.; Perry, P.; Brun, A.; Morales-Alonso, G. Behind the runway: Extending sustainability in luxury fashion supply chains. J. Bus. Res. 2018. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0148296318304673 (accessed on 20 September 2019). [CrossRef]

- Behnam, S.; Cagliano, R.; Grijalvo, M. How should firms reconcile their open innovation capabilities for incorporating external actors in innovations aimed at sustainable development? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 950–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, E.; Urbinati, A.; Chiaroni, D. Managerial practices for designing circular economy business models. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 561–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Taisch, M.; Mier, M.O. Influencing factors to facilitate sustainable consumption: From the experts’ viewpoints. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, A.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; Crecente, F. Sustainable business model innovation and acceptance of its practices among Spanish entrepreneurs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, L.; Tucci, C.L. Business Model Innovation. In The Oxford Handbook of Innovation Management; Dodgson, M., Gann, D.M., Phillips, N., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Pistoia, A.; Ullrich, S.; Göttel, V. Business Models: Origin, Development and Future Research Perspectives. Long Range Plann. 2016, 49, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, L.; Tucci, C.L.; Afuah, A. A Critical Assessment of Business Model Research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, M.P.P.; McAloone, T.C.; Pigosso, D.C.A. Business model innovation for circular economy and sustainability: A review of approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Saebi, T. Business models and business model innovation: Between wicked and paradigmatic problems. Long Range Plann. 2018, 51, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Winby, S. Organizational Models for Innovation. Available online: http://www.vps.ns.ac.rs/Materijal/mat936.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2019).

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation, 1st ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ritala, P.; Huotari, P.; Bocken, N.; Albareda, L.; Puumalainen, K. Sustainable business model adoption among S&P 500 firms: A longitudinal content analysis study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 216–226. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, R.; Puranam, P.; Tushman, M. Meta-organization design: Rethinking design in interorganizational and community contexts. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, R.H.; Peters, T.J.; Phillips, J.R. Structure is not organization. Bus. Horiz. 1980, 23, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, J.R. Designing Organizations; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miterev, M.; Mancini, M.; Turner, R. Towards a design for the project-based organization. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 35, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, E.E.; Worley, C.G. Designing organizations for sustainable effectiveness. Organ. Dyn. 2012, 41, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.; Miterev, M. The Organizational Design of the Project-Based Organization. Proj. Manag. J. 2019, 50, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, D.K. Norton Linking the Balance Scorecard to Strategy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 39, 53–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lages, L.F. VCW—Value Creation Wheel: Innovation, technology, business, and society. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4849–4855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Transforming the Balanced Scorecard from Performance Measurement to strategic management: Part I. Account. Horizons 2001, 15, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Transforming the Balanced Scorecard from Performance Measurement to Strategic Management: Part II. Account. Horizons 2001, 15, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaosman, H.; Morales-Alonso, G.; Brun, A. From a Systematic Literature Review to a Classification Framework: Sustainability Integration in Fashion Operations. Sustainability 2016, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.; Boons, F.; Baldassarre, B. Sustainable business model experimentation by understanding ecologies of business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 1498–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Rana, P.; Short, S.W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2015, 32, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunn, V.S.C.; Bocken, N.M.P.; van den Hende, E.A.; Schoormans, J.P.L. Business models for sustainable consumption in the circular economy: An expert study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, H.M. Conceptualising Global Strategic Sustainability and Corporate Transformational Change. Int. Mark. Rev. 2009, 26, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Design for the Triple Top Line: New Tools for Sustainable Commerce. Corp. Environ. Strateg. 2002, 9, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidumolu, R.; Prahalad, C.K.; Rangaswami, M.R. Why Sustainability Is Now the Key Driver of Innovation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Girotra, K.; Netessine, S. OM Forum—Business Model Innovation for Sustainability. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2013, 15, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M.; Cennamo, C.; Neumann, K. Beyond What and Why: Understanding Organizational Evolution Towards Sustainable Enterprise Models. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W. Towards a sufficiency-driven business model: Experiences and opportunities. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2016, 18, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. Design thinking to enhance the sustainable business modelling process—A workshop based on a value mapping process. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1218–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran-Encalada, J.A.; Paucar-Caceres, A. A system dynamics sustainable business model for Petroleos Mexicanos ( Pemex ): Case based on the Global Reporting Initiative. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2012, 63, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reim, W.; Parida, V.; Örtqvist, D. Product - Service Systems (PSS) business models and tactics - a systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłoński, A. Scalability of Sustainable Business Models in Hybrid Organizations. Sustainability 2016, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłoński, A.; Jabłoński, M. Research on Business Models in their Life Cycle. Sustainability 2016, 8, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antikainen, M.; Valkokari, K. A Framework for Sustainable Circular Business Model Innovation. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2016, 6, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.; Rios, C.D.L.; Rowe, Z.; Charnley, F. A Conceptual Framework for Circular Design. Sustainability 2016, 8, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1979, 57, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, A.D. Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of American Enterprise; MIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, A.; Paquin, R.L. The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, M. Designing the Business Models for Circular Economy — Towards the Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm. Acad. Manag. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Leih, S.; Linden, G.; Teece, D.J. Business Model Innovation and Organizational Design. In Business Model Innovation: The Organizational Dimension; Foss, N.J., Saebi, T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mirvis, P.; Googins, B.; Kinnicutt, S. Vision, mission, values. Guideposts to sustainability. Organ. Dyn. 2010, 39, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaninger, M. Organizing for sustainability: A cybernetic concept for sustainable renewal. Kybernetes 2015, 44, 935–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worley, C.G.; Feyerherm, A.E.; Knudsen, D. Building a collaboration capability for sustainability. How Gap Inc. is creating and leveraging a strategic asset. Organ. Dyn. 2010, 39, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury-Huang, H. Sustainability by collaboration. The SEER case. Organ. Dyn. 2010, 39, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.J. Climate change as a cultural and behavioral issue. Addressing barriers and implementing solutions. Organ. Dyn. 2010, 39, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Buhovac, A.R.; Yuthas, K. Why Nike kicks butt in sustainability. Organ. Dyn. 2010, 39, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, T.; Lettl, C. The wider implications of business-model research. Long Range Plann. 2018, 51, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.V.; Harrison, N.S. Organizational Design and Environmental Performance: Clues from the Electronics Industry. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Boland, R.J.; Lyytinen, K. Organization Design to Organization Designing. Organ. Sci. 2006, 17, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Buhovac, A.R. Solving the sustainability implementation challenge. Organ. Dyn. 2010, 39, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, A.; Cagliano, R. Environmental and social sustainability priorities. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2015, 35, 216–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, M.; Voigt, K.I.; Brem, A. Business Models for Corporate Innovation Management: Introduction of A Business Model Innovation Tool for Established Firms. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2018, 22, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, E.; Arnold, M.; Bendul, J.C. Business models for sustainable innovation—An empirical analysis of frugal products and services. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Focus | Archetypes |

|---|---|

| Environment |

|

| Social |

|

| Economic |

|

| Reference | Strategy | Structure | Process | Rewards | People |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geissdoerfer; Vladimirova; Evans (2018) [10] | X | ||||

| Bocken, Short, Rana, Evans (2014) [14] | X | X | X | ||

| Ünal, Urbinati, Chiaroni, (2019) [17] | X | X | |||

| Bocken, Rana, Short (2015) [44] | X | X | |||

| Borland (2009) [45] | X | X | |||

| Nidumolu et al. [47] | X | X | |||

| Duran-Encalada and Paucar-Caceres (2012) [48] | X | X | |||

| Girotra and Netessine (2013) [49] | X | X | X | ||

| Zollo et al. (2013) [50] | X | X | X | X | |

| Reim et al. (2015) [51] | X | X | X | ||

| Antikainen and Valkokari (2016) [52] | X | X | X | ||

| Bocken, de Pauw, Bakker, van der Grinten (2016) [53] | X | X | X | ||

| Bocken, Short (2016) [54] | X | X | X | ||

| Geissdoerfer, Bocken, Hultink (2016) [55] | X | X | X | ||

| Jablonski and Jablonski (2016) [56] | X | X | |||

| Jablonski (2016) [57] | X | X | |||

| Joyce and Paquin (2016) [58] | X | X | X | ||

| Lewandowski (2016) [59] | X | X | X | ||

| Moreno et al. (2016) [60] | X | X | X |

| System Boundaries | Sustainable Business Models | Organizational Design Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational | X | X |

| Interorganizational | X | - |

| Ecosystem | X | - |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lemus-Aguilar, I.; Morales-Alonso, G.; Ramirez-Portilla, A.; Hidalgo, A. Sustainable Business Models through the Lens of Organizational Design: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195379

Lemus-Aguilar I, Morales-Alonso G, Ramirez-Portilla A, Hidalgo A. Sustainable Business Models through the Lens of Organizational Design: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2019; 11(19):5379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195379

Chicago/Turabian StyleLemus-Aguilar, Isaac, Gustavo Morales-Alonso, Andres Ramirez-Portilla, and Antonio Hidalgo. 2019. "Sustainable Business Models through the Lens of Organizational Design: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 11, no. 19: 5379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195379

APA StyleLemus-Aguilar, I., Morales-Alonso, G., Ramirez-Portilla, A., & Hidalgo, A. (2019). Sustainable Business Models through the Lens of Organizational Design: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 11(19), 5379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195379