How to Attract Talented Expatriates: The Key Role of Sustainable HRM

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Sustainable HRM and the Attractiveness of a Subsidiary

2.2. Host Country Images of Subsidiaries

2.3. Family Support Policies

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Procedures

3.4. The Attractiveness of a Subsidiary as a Dependent Variable

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caligiuri, P.M. The big five personality characteristics as predictors of expatriate’s desire to terminate the assignment and supervisor-rated performance. Pers. Psychol. 2000, 53, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.Y.; Gong, Y.; Peng, M.W. Expatriate knowledge transfer, subsidiary absorptive capacity, and subsidiary performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 927–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, M.J.; Haines, V.Y., III; Saba, T. Gender, family ties, and international mobility: Cultural distance matters. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Froese, F.J. Expatriation willingness in Asia: The importance of host-country characteristics and employees’ role commitments. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 3414–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, B.; Berg, N.; Holtbrügge, D. Expatriate performance in terrorism-endangered countries: The role of family and organizational support. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 24, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Eccher, U.; Duarte, H. How images about emerging economies influence the willingness to accept expatriate assignments. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynes, S.L. Recruitment, job choice, and post-hire consequences: A call for new research directions. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2nd ed.; Dunnette, M.D., Hough, L.M., Eds.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palto Alto, CA, USA, 1991; Volume 2, pp. 399–444. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, I.M.; Eroglu, S. Measuring a multi-dimensional construct: Country image. J. Bus. Res. 1993, 28, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.H.; Kim, E.M. Overcoming country-of-origin image constraints on hiring: The moderating role of CSR. Asian. Bus. Manag. 2017, 16, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GMT. Global Mobility Trends Survey Report. 2016. Available online: http://globalmobilitytrends.bgrs.com/ (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Haslberger, A.; Brewster, C. The expatriate family: An international perspective. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 324–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharenou, P. Disruptive decisions to leave home: Gender and family differences in expatriation choices. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2008, 105, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarova, M.; Westman, M.; Shaffer, M.A. Elucidating the positive side of the work-family interface on international assignments: A model of expatriate work and family performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Ehnert, I. Sustainable Human Resource Management: A Conceptual and Exploratory Analysis from a Paradox Perspective; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kramar, R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macke, J.; Genari, D. Systematic literature review on sustainable human resource management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I. Sustainability Issues in Human Resource Management: Linkages, theoretical approaches, and outlines for an emerging field. In Proceedings of the 21st EIASM Workshop on SHRM, Aston, UK, 30–31 March 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T.D. Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A. Connecting work—Family policies to supportive work environments. Group Organ. Manag. 2009, 34, 206–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J.H.; Casper, W.J.; Matthews, R.A.; Allen, T.D. Family-supportive organization perceptions and organizational commitment: The mediating role of work—Family conflict and enrichment and partner attitudes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 606–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Investment Report 2017. Available online: https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2017_en.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- Cho, T.; Hutchings, K.; Marchant, T. Key factors influencing Korean expatriates’ and spouses’ perceptions of expatriation and repatriation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 1051–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevičiūtė, Ž.; Savanevičienė, A. Designing sustainable HRM: The core characteristics of emerging field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Prins, P.; Van Beirendonck, L.; De Vos, A.; Segers, J. Sustainable HRM: Bridging theory and practice through the ‘Respect Openness Continuity (ROC)’-model. Manag. Rev. 2014, 25, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehling, C.; Hernandez, A.G.; Osland, J.; Osland, A.; Deller, J.; Tanure, B.; Neto, A.C.; Sairaj, A. An exploratory study of the role of HRM and the transfer of German MNC sustainability values to Brazil. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2009, 3, 176–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B.; Zander, U. Knowledge of the firm and the evolutionary theory of the multinational corporation. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1993, 24, 625–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Mahoney, J.T. Why a multinational chooses expatriates: Integrating resource-agency, and transaction costs perspectives. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 457–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Keon, T.L. Organizational attractiveness: An interactionist perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, F.; Van Hoye, G.; Schreurs, B. Examining the relationship between employer knowledge dimensions and organizational attractiveness: An application in a military context. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2005, 78, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Forret, M.; Hendrickson, C. Applicant attraction to firms: Influences of organization reputation, job and organizational attributes, and recruiter behavior. J. Vocat. Behav. 1998, 52, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoye, G.; Saks, A.M. The instrumental-symbolic framework: Organizational image and attractiveness of potential applicants and their companions at a job fair. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 60, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltokorpi, V.; Froese, F. Organizational expatriates and self-initiated expatriates: Who adjusts better to work and life in Japan? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 20, 1096–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allred, A.; Chakraborty, G.; Miller, S.J. Measuring images of developing countries: A scale development study. J. Euromark. 2000, 8, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newburry, W.; Gardberg, N.A.; Belkin, L.Y. Organizational attractiveness is in the eye of the beholder: The interaction of demographic characteristics with foreignness. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 666–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, F.; Garrett, T. Organizational attractiveness of foreign-based companies: A country of origin perspective. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2010, 18, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job market signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Cable, D.M. Firm reputation and applicant pool characteristics. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhart, K.H.; Ziegert, J.C. Why are individuals attracted to organizations? J. Manag. 2005, 31, 901–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highhouse, S.; Thornbury, E.E.; Little, I.S. Social-identity functions of attraction to organizations. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2007, 103, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinsky, E.; Aumann, K.; Bond, J.T. Times are changing: Gender and generation at work and at home in the USA. In Expanding the Boundaries of Work-Family Research; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; Volume 13, pp. 279–296. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, K.; Galinsky, S. National Study of Employers, the Families and Work-Institute. 2014. Available online: http://familiesandwork.org/site/research/reports/2014nse.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2019).

- Friedman, D.E. Work and family: The new strategic plan. Hum. Resour. Plann. 1992, 13, 297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. On the family as a realized category. Theory Cult. Soc. 1996, 13, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezra, M.; Deckman, M. Balancing work and family responsibilities: Flexible and childcare in the federal government. Public Adm. Rev. 1996, 56, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.; McKenna, S. Exploring relationships with home and host countries: A study of self-directed expatriates. Cross Cult. Manag. 2006, 13, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, R.; Yun, S.; Russell, J.E. Antecedents and consequences of the perceived adjustment of Japanese expatriates in the USA. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2002, 13, 1224–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harrison, D.A.; Shaffer, M.A.; Bhaskar-Shrinivas, P. Going places: Roads more and less traveled in research on expatriate experiences. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2004; Volume 23, pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Turban, D.B. Organizational attractiveness as an employer on college campuses: An examination of the applicant population. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.B. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Slocum, J.W., Jr. Individual differences and expatriate assignment effectiveness: The case of US-based Korean expatriates. J. World Bus. 2008, 43, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.D.; Tung, R.L. Opportunities and challenges for expatriates in emerging markets: An exploratory study of Korean expatriates in India. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 1029–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, F.S.; Hall, D.T. Dual career: How do couples and companies cope with the problems? Organ. Dyn. 1978, 6, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickmann, M.; Doherty, N.; Mills, T.; Brewster, C. Why do they go? Individual and corporate perspectives on the factors influencing on the decision to accept an international assignment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 731–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (Years) | n | (%) | Education | n | (%) |

| 24–30 | 38 | (8.76) | High school | 54 | (12.44) |

| 31–35 | 86 | (19.82) | Associate degree | 75 | (17.28) |

| 36–40 | 95 | (21.89) | Bachelor’s degree | 259 | (59.68) |

| 41–45 | 101 | (23.27) | Master’s degree | 40 | (9.22) |

| 46–50 | 53 | (12.21) | Ph.D. degree | 6 | (1.38) |

| Above 50 | 61 | (14.05) | |||

| International Experience (Years) | n | (%) | Working Experience (Years) | n | (%) |

| None | 291 | (67.05) | Below 1 | 28 | (6.45) |

| 0–1 | 83 | (19.12) | 1–4 | 65 | (14.98) |

| 1–4 | 46 | (10.60) | 5–10 | 119 | (27.42) |

| 5–10 | 11 | (2.54) | Above 10 | 222 | (51.15) |

| Above 10 | 3 | (0.69) |

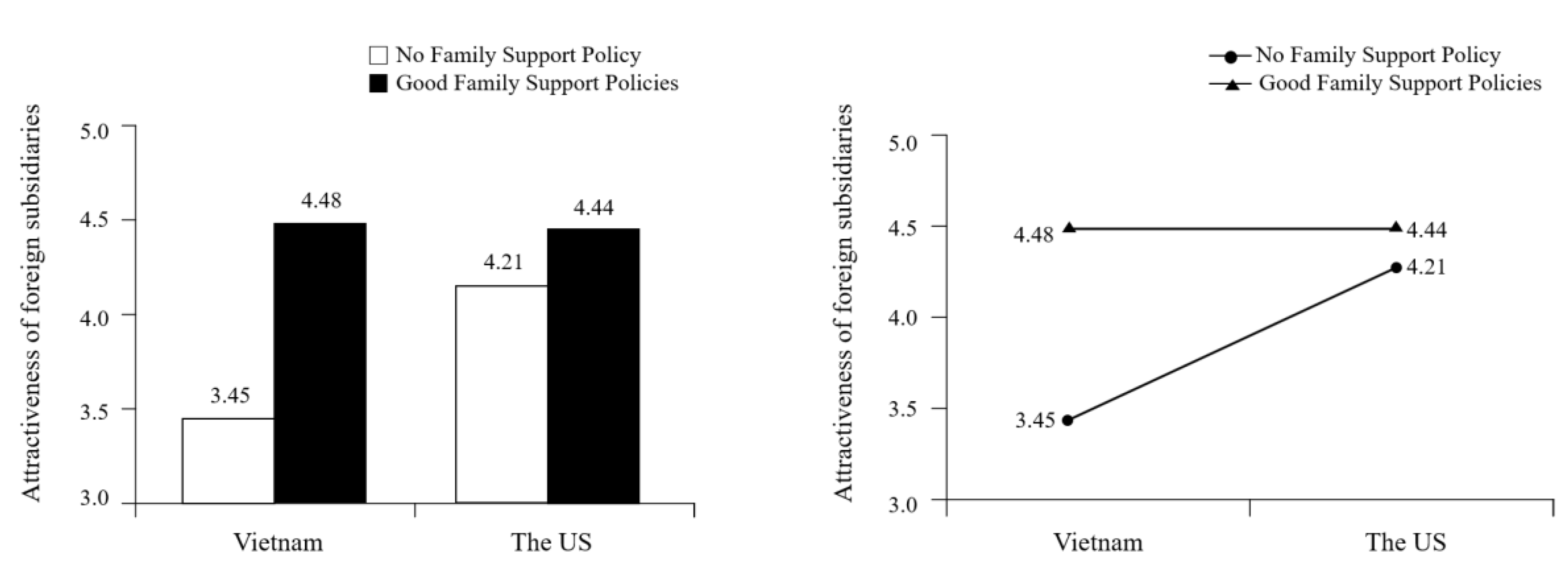

| df | MS | F-Value | p-Value | Partial η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Host-locations | 1 | 14.612 | 15.597 | 0.000 | 0.035 |

| Family support policies | 1 | 42.349 | 45.205 | 0.000 | 0.095 |

| Host-locations × Family support policies | 1 | 17.430 | 18.605 | 0.000 | 0.041 |

| Error | 430 | 0.937 |

| df | SS | F-Value | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No vs. Good family support policies | Vietnam | 1 | 54.754 | 52.417 | 0.000 |

| The US | 1 | 2.840 | 2.705 | 0.101 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, G.; Kim, E. How to Attract Talented Expatriates: The Key Role of Sustainable HRM. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5373. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195373

Hong G, Kim E. How to Attract Talented Expatriates: The Key Role of Sustainable HRM. Sustainability. 2019; 11(19):5373. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195373

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Gahye, and Eunmi Kim. 2019. "How to Attract Talented Expatriates: The Key Role of Sustainable HRM" Sustainability 11, no. 19: 5373. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195373

APA StyleHong, G., & Kim, E. (2019). How to Attract Talented Expatriates: The Key Role of Sustainable HRM. Sustainability, 11(19), 5373. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195373