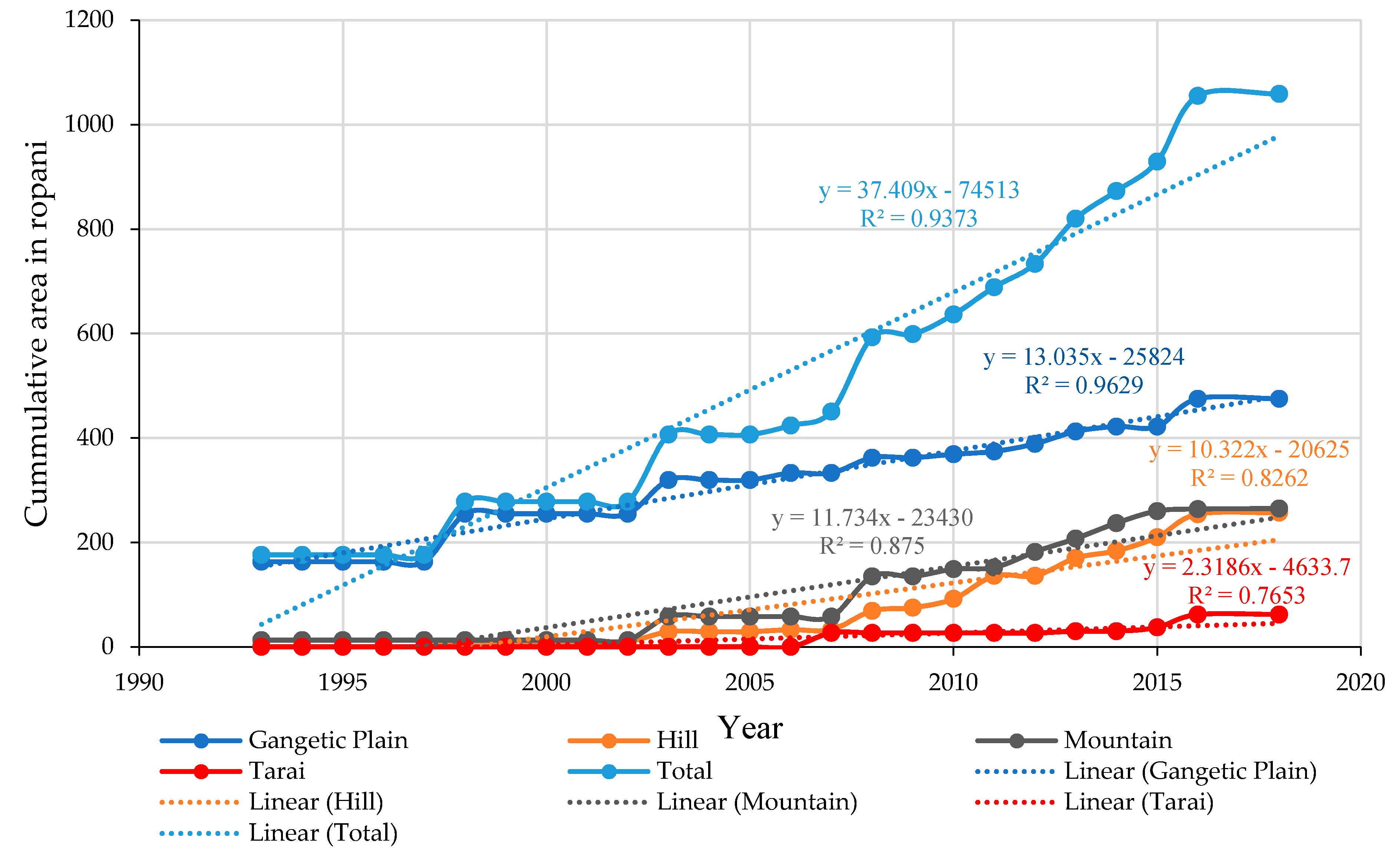

4.1. Farmland Abandonment in Different Physiographic Regions

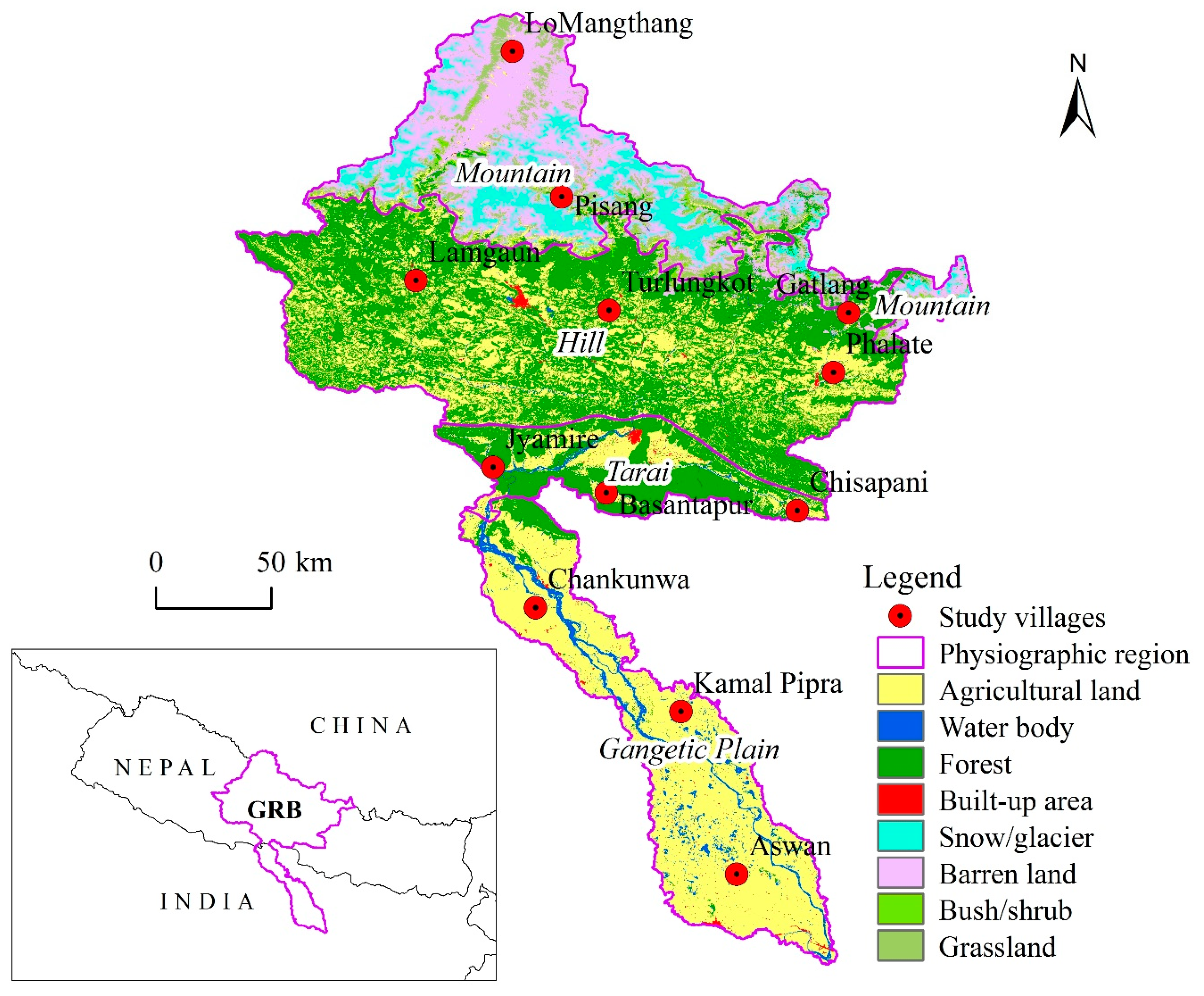

The physiographic regions of Nepal and India differ in terms of topography, the availability of agricultural land, productivity, environment, and overall development [

29,

37]. Therefore, the proportion of farmland abandonment varied among the physiographic regions of the GRB.

Mountain region: Both the percentage of household abandoning farmland and the proportion of area under abandonment were comparatively higher in the Mountain region. Farmland abandonment in the mountainous regions is expected to increase in the future [

24,

38]. One study found that a total of 28% farmland was abandoned from 2000 to 2010 in China’s mountainous areas, where farmlands were freely abandoned by farmer for the Grain for Green project (1999) to convert farmland to forest or grassland to mitigate soil erosion in the sloping Mountain region of China [

19]. China and Nepal have a similar Mountain region topography in the China-Nepal border region, although the percentages of farmland abandonment rates are different due to policy and decision of household level. Farmland abandonment has also increased in the European mountain region in recent years. Based on remote sensing observations, 7.6 million hectares of farmland were permanently abandoned, particularly in Eastern Europe, Southern Scandinavia and Europe’s mountainous regions from 2001 to 2012 [

39]. The farmland abandonment in the Spanish Mountain regions since the 1950s resulted in decreased productivity with changing landscape, with woodland areas increasing from 10% to 37% and scrubland increased 42% to 60% during 1956–2001 [

40]. From previous studies, it is clear that farmland abandonment is one of the pathways of land use change in Mountain regions everywhere in the world. The current study also shows a similar trend to other Mountain regions, but the process of farmland abandonment and spatio-temporal extent are different due to differences in the change in demography as well as major sources of livelihood at the household level and government policy.

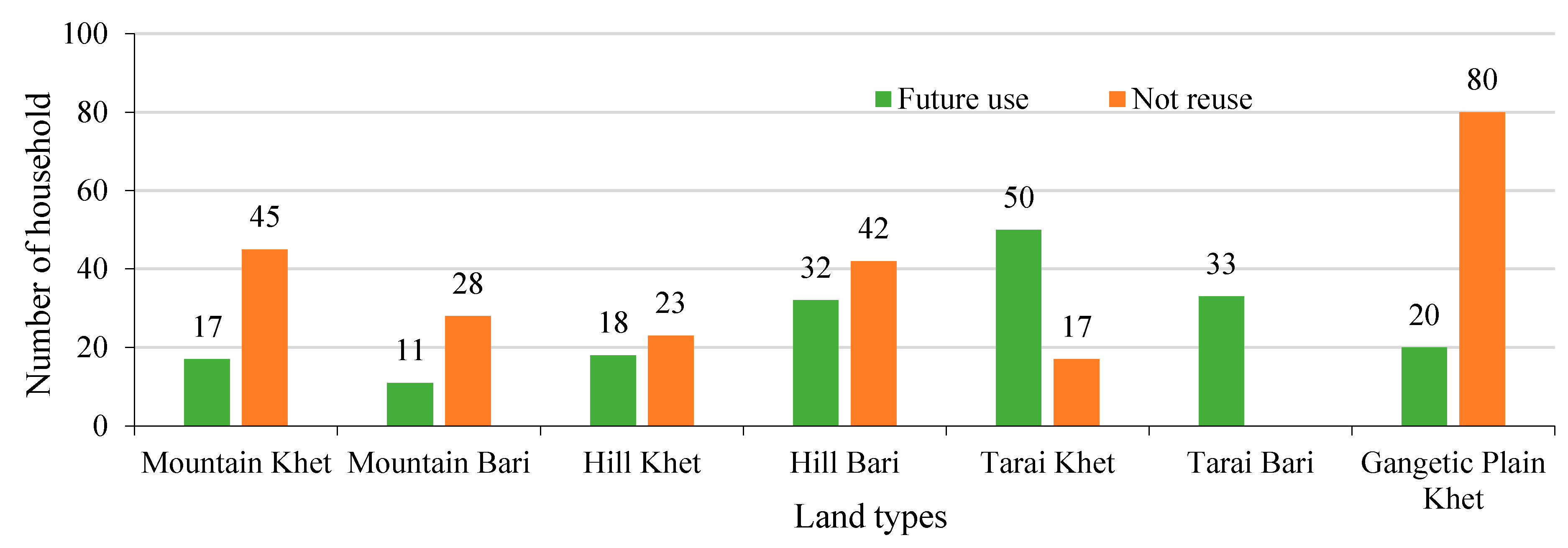

Hill region: Farmland abandonment was also found to be high in the Hill region of the GRB. Historically, farmland abandonment has occurred more frequently in the Hill region of Nepal than in the Tarai region. One previous study revealed that the abandoned farmland was 44%, 23% and 33% in the upper-Hill, lower mid-Hill and lower plains regions, respectively, of the country in 2012 [

20], whereas GRB Hill revealed 15%, which is almost half of what was reported previously. This lower proportion found in this study might be due to the selection of the study area and differences in methodology. Paudel et al. (2014) categorized upper and lower mid-Hill and used an actor-oriented approach, which was not statistically tested. A parcel-level analysis showed that approximately 49% and 37% of khet and bari land were abandoned, respectively, in the Sikles and Parche villages of the GRB [

26]. Due to variation in the selection of villages, study time, and methods, the results varied within the Hill region. Khanal and Watanabe (2006) conducted household survey in 78 households from two villages during 1999–2000. After 2000, Nepal witnessed many changes, particularly in population growth, increased foreign migration, political changes and others [

8,

41,

42]. Thus, it is clear that farmland abandonment is common in the Hill region and has been an increasing trend in recent years. The percentage of abandoned farmland is comparatively high in the Hilly and Mountainous regions. Our study also showed similar trend as observed in previous studies.

Tarai region: The Tarai region has the lowest level of farmland abandonment of all the regions in the study area. This is mainly due to its fertile agricultural land with access to an irrigation facility. Farmland abandonment has been found to be lowest in plains regions in other countries as well. For example, in Argesş County in central Romania, the plains region had 10% farmland abandonment during 1990–1995 [

43]. Müller et al. (2009) also studied Mountain, Hill and Plain zones (flat land) in their study and found comparatively lower abandonment in the plains among the zones. The low level of farmland abandonment in the Tarai region of GRB can be attributed to overall high land fertility, access to irrigation, and high land value. Nevertheless, studies on farmland abandonment processes in the Tarai region of Nepal are generally lacking.

GP region: The GP region had the second-highest level of farmland abandonment. The trend of farmland abandonment has a long history in the GP region. According to FGD and KII, there is an increasing trend of farmland abandonment. The Tarai and GP regions have almost the same topography, although farmland abandonment is higher in the GP region than in the Tarai region. The Tarai (Nepal) and GP (India) regions have similar bio-physical context, but frequent occurrence of drought and flood on the one hand and the difference in the socio-economic context, as well as the policies, legislation and governance systems on the other, could be the reasons for the differing rate of farmland abandonment.

4.2. Factors Influencing Farmland Abandonment

Mountain region: Different variables have played significant roles in farmland abandonment across the GRB. In the Mountain region, distance to market, decreasing population and age of household head were the predominant factors contributing to farmland abandonment. One of the major reasons for decreasing population is out-migration. According to the KIIs and FGDs conducted in the Mountain region, out-migration has greatly increased since the 2000s, with most migrants going abroad for labor employment. The change in population (i.e., decreased labor force) was found to be a significant cause and had a positive relationship with farmland abandonment in the Mountain region. According to the national census of Nepal, the population is decreasing in the Mountain region. The population of the Mountain region accounted for 9.9% of Nepal’s total population in 1971; this percentage decreased to 8.7%, 7.8%, 7.3% and 6.7% in 1981, 1991, 2001 and 2011, respectively [

44]. One study has found that abroad labor permits were officially recorded at 3605 in 1993–1994 and increased to 453,543 in 2012–2013; among them, 4.3% from Mountain, 45.1% from Hill and 50.6% from Tarai region of Nepal [

45]. In addition, international migration such as rural mountainous areas to semi-urban and urban areas are very common in Nepal, resulting in a decline in farmland area and an increase in shrubland/grassland [

46]. Based on the Nepal census report of 2001, the net number of migrants was recorded to be 255,000 immigrants from Mountain, and 831,000 from the Hill region [

45]. The country’s absent population was recorded at 762,181 in 2001, which increased by more than two-and-a-half-fold (1,921,494 population) in 2011 [

44,

47]. From the various historical records, the migration (rural-urban and abroad) trend has been very high in Nepal. The present study also reported the same results as previous national and regional level studies that population change (out-migration) is the major cause of farmland abandonment in the Mountain region of the GRB. One recent study also supported that migration and remittances were a significant cause of farmland abandonment in the Mountain region of Nepal [

23]. This study shows that the extension of road network and access to market centers and easily available food encourage farmland abandonment in the Mountain region. According to the household survey, remittance is used primarily to buy food to support their household.

Hill region: The long distance to farmland from residence is an important factor contributing to farmland abandonment in the Hill region of the GRB. In the Hill region, farmlands located far from residence require high labor and other inputs and are less desirable to farmers compared to the closer farmlands near residences. Paudel et al. (2014) have also reported that distance from residence to farmland was an important factor of farmland abandonment. Farmlands are also being abandoned in areas located far from farmers’ residences in rural areas of China [

24,

48] as well as India [

22]. Farmers estimate tentative production and input cost and make decisions about whether to continue or abandon far-off farmlands. Similarly, the availability of irrigation plays an important role in farmland abandonment. In the Hill region of Nepal, a total of 40% of agricultural land lacks irrigation facilities and the agriculture production on these lands depends solely on monsoon rain [

49]. Among the irrigated areas of Nepal, around 70% of the irrigation systems are managed by ‘Farmer Managed Irrigation Systems’, however, with environmental degradation, declining water resources, and high competition in the allocation of water resources, irrigation systems face major challenges [

50]. In addition, irrigation problems are compounded by the presence of steep slope and frequent occurrences of floods and landslides in the Hill and Mountain regions in the country. In the absence of irrigation, the productivity of traditionally used crops decreases and there is less potential to increase cropping intensity. As a result, areas without irrigation facilities are often abandoned. Agroforestry programs on abandoned farmland could be an alternative so that natural hazards (floods, soil erosion, and landslides) could be reduced and at the same time, people could benefit financially. The land use policy, particularly increases in land tax on abandoned farmland could also be another measure to minimize farmland abandonment. Another important factor for farmland abandonment in the Hill region is the distance from residence to market which was also found to be significant for the Mountain region. The occupation of household head and training obtained by family members on agriculture development were also found to be important determinants for farmland abandonment. The availability of natural capital, i.e., farm size, is another important determinant for farmland abandonment. As the farm size increases, the chances for farmland abandonment increases.

Tarai region: Household head with off-farm occupations was the key cause of farmland abandonment in the Tarai region. Urbanization in the Tarai region is rapid due to inter-regional migration for employment opportunities and better a life [

51]. Since the late 1950s, migration to lower elevations (Tarai region) has mainly been caused by the higher agricultural productivity and the better quality of life afforded by the Tarai region [

52]. Still, the Tarai region is gaining population from the Hill and Mountain regions, as Tarai provides more economic options to migrants. Population increase is mainly due to in-migration, more fertile soil, and advanced agriculture opportunities in the Tarai region [

8,

37]. One study presented that population changes caused by political events, such as the democratic movement in 1951 and the more recent Maoist revolution of 2005/2006, have caused significant population movements throughout the country, particularly in the Tarai region [

44]. The opportunities for changing occupation from agricultural to off-farm (non-agriculture), such as business and other service-oriented jobs, are creating farmland abandonment in the Tarai region.

GP region: The GP region is dominated by farmland. However, due to the lack of irrigation facilities and market centers, the proportion of abandoned farmland is higher and it is increasing. Farming practices are directly affected by the lack of irrigation facilities in Bihar [

53,

54]. Farmers are faced with irregular monsoon rains, which regularly result in flooding, crop damage, and waterlogging problems in Bihar [

54]. The Bihar government has introduced several subsidies and relief programs to minimize the effects of drought on agriculture; however, due to uncertainties and high transaction costs, it is not very effective to stimulate farmers to bring the land under cultivation after it has been damaged by floods and drought [

55,

56]. Currently, out of the 55.54 hundred thousand hectares of irrigated farmland in Bihar, only 30.64 hundred thousand hectares have irrigation facilities [

57]. Sri Lankan farmers are currently adopting short season crops to overcome some of the drought effects [

58] and more farmers use groundwater irrigation for farming in drought-prone areas in Bangladesh [

59]. Drip irrigation has also been found to be another better method in water scarce areas. One study revealed that due to resources saving and cost-effectiveness, farmers have started a drip irrigation system in southern India [

60]. Drip irrigation and crop diversification (drought tolerance crops, short-season crops) provide more effective ways to conserve water and can help minimize farmland abandonment in the GP region. In addition, groundwater could be an efficient method of irrigation in water scarce-areas. Nevertheless, the availability of foods/grains imported from elsewhere has supported the farmers who lacked adequate food supply. The availability of imported foods in the near-market showed a positive relationship to farmland abandonment in the GP region.

4.3. Farmers’ Perceptions about the Reasons for Farmland Abandonment

Various perceptions of farmers regarding farmland abandonment were obtained from the different physiographic regions. The Mountain region has suffered a decreased agricultural labor force. According to FGDs, during the conservation and harvesting seasons, laborers have to be hired from other places with higher wages in the Hill and Mountain regions. During 1999–2014, abroad migration of youth resulted labor shortages in the village and consequently, more farmlands were left abandoned. Such processes of change have also been reported from the Andhi Khola watershed, which is also located in the Hill region of the GRB [

8]. In addition, as the males migrate, the burden of agricultural work is also left to women and ultimately, the farmland is left abandoned [

41].

Climate change effects have been recognized in all the regions of the GRB. In a previous study, 92% of respondents in the Chitwan-Annapurna region in Nepal reported experiencing climate change effects over the last 15 years, including unpredictable precipitation, drought, decreased water resources and changes in cropping patterns and phenology [

61]. In the current study, approximately 49% and 91% of farmers reported that the negative effects of climate change had contributed to farmland abandonment in the Mountain and Hill regions, respectively. Previous studies have reported the effect of climate change on farming practices manifested by increased temperature, decreased rainfall, decreased water resources, and drought [

62,

63,

64].

Off-farm activities, mainly in the tourism industry, have been increasing in the Mountain region and are becoming a major source of income and an attractive way of life for people of the Mountain region in Nepal [

65]. Based on tourism statistics, the total number of trekkers increased significantly from 2714 to 23,569 from 2005 to 2017 and the total number of tourist increased from 375,398 to 940,210 [

66]. This increase in trekking and tourism has resulted in increased off-farm activities in the Mountain region and discouraged crop farming and consequently, an increase in farmland abandonment.

The effects of climate change, high agricultural input costs, out-migration and long distances between residences and farmlands were perceived as the major factors driving farmland abandonment in the Hill region. A study based on household surveys found that labor shortages resulting from out-migration had caused farmland abandonment in the hilly and mountainous regions of Nepal [

67]. In recent years, increasing labor costs have also contributed to farmland abandonment in many rural areas in China [

68].

In the Tarai region, around 50% farmers perceived the decrease in production as the main cause of farmland abandonment. It is obvious that according to the household surveys, FGDs and KIIs, only marginal land near to the forest, land at risk of flooding, and non-irrigated land were abandoned in this region. In the GP region, almost all farmers believe that the effect of climate change (i.e., drought, flood, decrease of water resources) encourages the farmland abandonment phenomenon. Bihar is also known as the multi-disaster prone state, mostly for recurrent floods, drought, and earthquakes [

69]. Staple crops are already vulnerable due to drought and high costs of irrigation [

56], therefore farmers have decreased interests in crop variability, particularly in drought-prone areas in Bihar [

70]. Increases in dry periods and longer-growing periods have negatively affected crop production in Bihar [

71]. Fluctuations in agricultural output have directly affected more than 36 million Bihari people in India [

72]. Approximately 51% of people in the Bihar area are engaged in the agricultural sectors; however, the crop production in Bihar is lower than in other states of India [

54]. Changing occupations are also creating labor shortages and contributing to farmland abandonment in the GP region. However, farmers are adopting alternative crops, such as banana and sugarcane, in areas previously used for paddy and wheat production in order to cope with the risk of climate change [

73]. Such changes in cropping varieties are not commonly used in the study area. One of the policy provisions for reducing farmland abandonment could be emphasis on the introduction of crop varieties resistant to drought.