Determination of Managers’ Attitudes Towards Eco-Labeling Applied in the Context of Sustainable Tourism and Evaluation of the Effects of Eco-Labeling on Accommodation Enterprises

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Eco-Label

2.2. Eco-Labels in Tourism and Its Historical Development

2.3. Purpose of Eco-Labels in Tourism

3. Materials and Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measurement Instrument

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Respondent Characteristics

4.2. Results of Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.3. Clustering Analysis Results

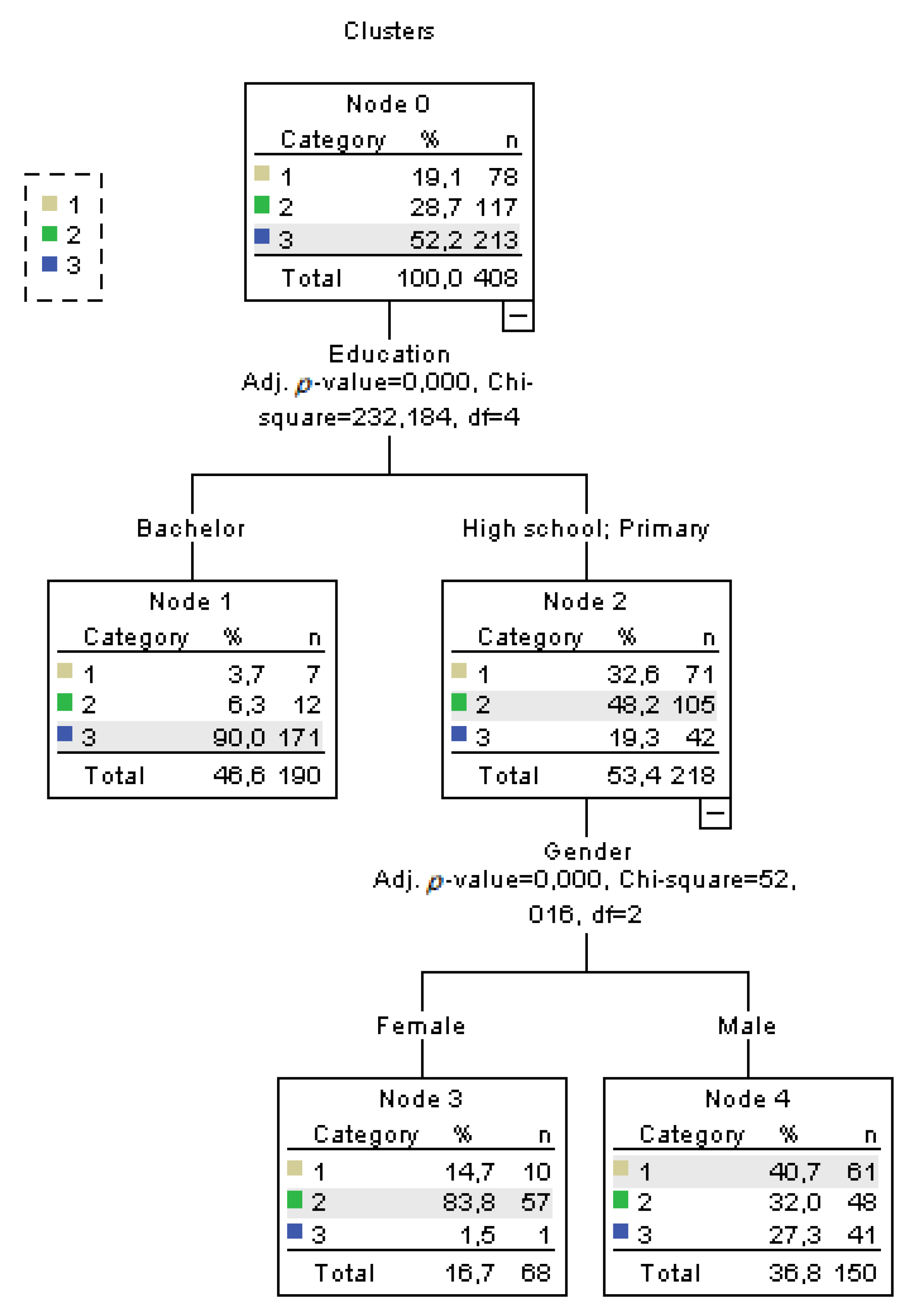

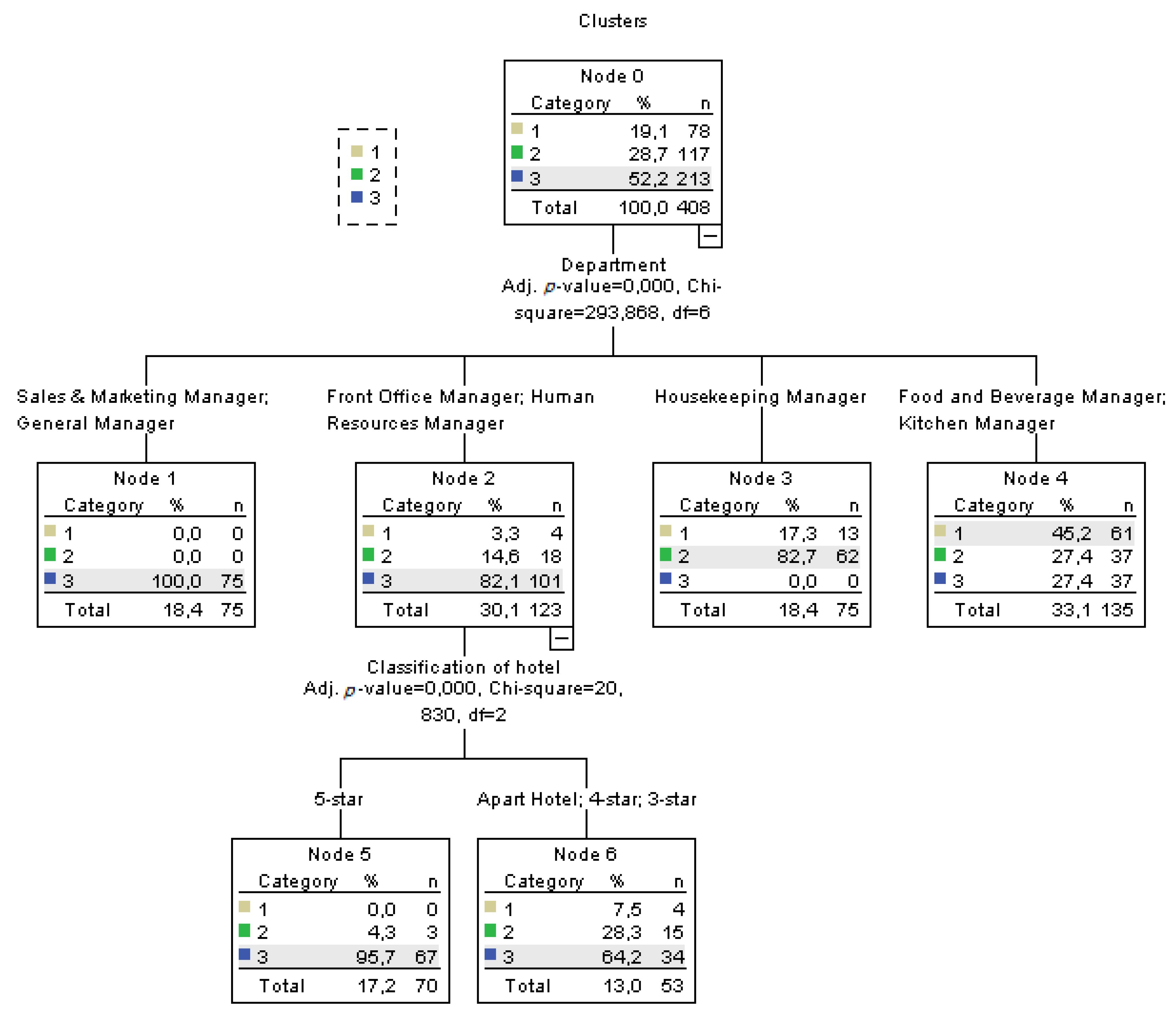

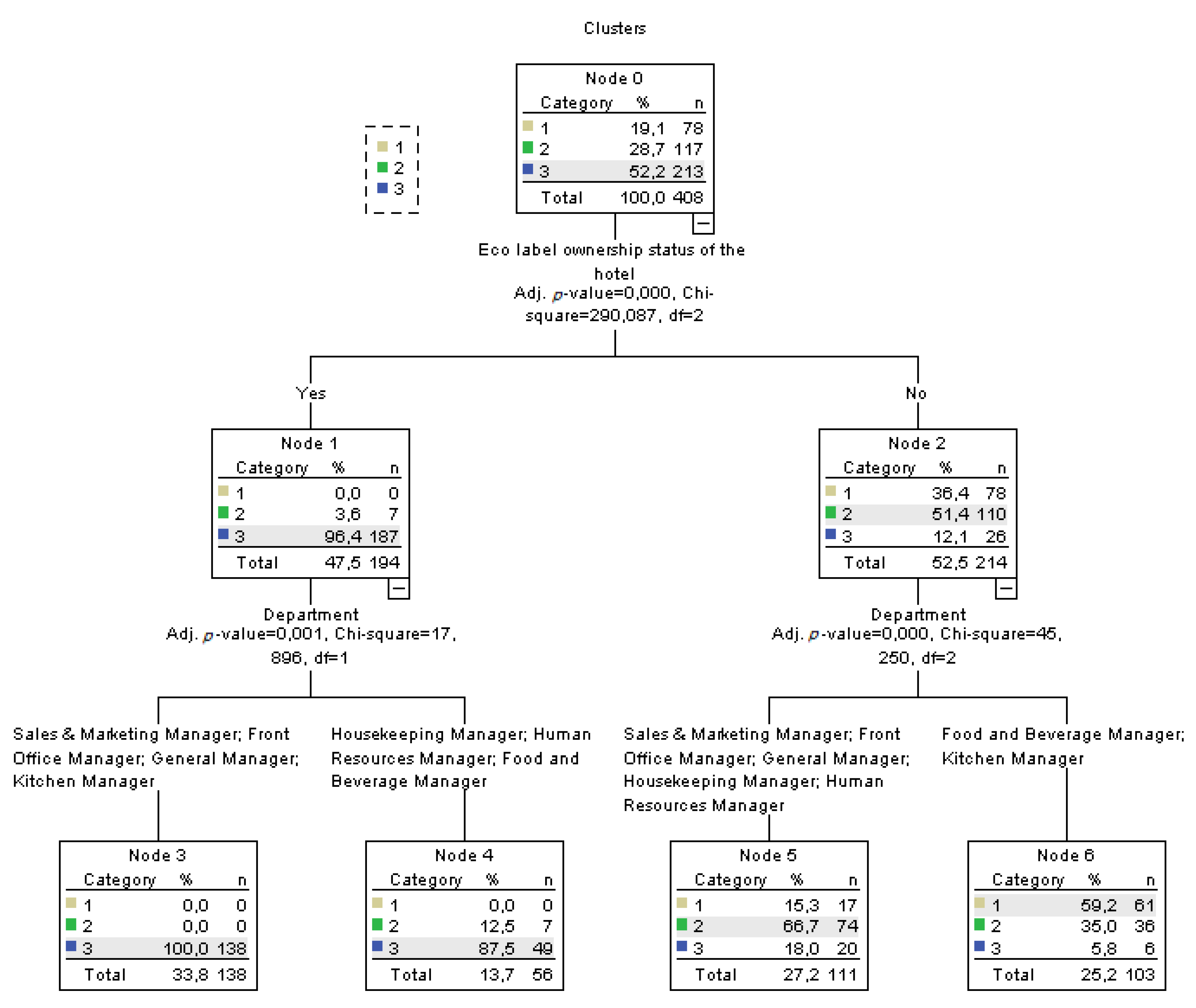

4.4. CHAID Analysis Results

4.5. Results of Eco-Labeling Activities on Accommodation Businesses

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gössling, S.; Peeters, P. Assessing tourism’s global environmental impact 1900–2050. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Global environmental consequences of tourism. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2002, 12, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutty, M.; Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. The global effects and impacts of tourism: An overview. In Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Hall, C.M., Scott, D., Gössling, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 36–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M. An Introduction to Tourism and Global Environmental Change. In Tourism and Global Environmental Change; Gössling, S., Hall, C.M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M.; Ceron, J.P.; Dubois, G. Consumer behaviour and demand response of tourists to climate change. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D. Climate Change and Sustainable Tourism in the 21st Century. In Tourism Research: Policy, Planning, and Prospects; Cukier, J., Ed.; Department of Geography Publication Series; University of Waterloo: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2006; pp. 175–248. [Google Scholar]

- Dinan, C.; Sargeant, A. Social Marketing and Sustainable Tourismis There a Match? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R. Tourism Ecolabels. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlüönen, K.; Kızanlıklı, M.M.; Arslan, E. Otel İşletmelerindeki Eko-Etiket ve Sistem Yönetim Belgelerinin Belirlenmesine Yönelik Bir Araştırma, 12; Ulusal Turizm Kongresi Bildiriler Kitabı: Düzce, Türkiye, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, O.I.; Iacobaş, P.; Nedelea, A.M. Marketing Research Regarding Tourism Business Readiness For Eco-Label Achievement (Case Study: Natura 2000 Crişul Repede Gorge-Padurea Craiului Pass Site, Romania). Ecoforum J. 2016, 5, 224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R. Tourism Ecocertification in the International Year of Ecotourism. J. Ecotourism 2002, 1, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brecard, D.; Hlaimi, B.; Lucas, S.; Perraudau, Y.; Salladarre, F. Determinants of Demand for Green Products: An Application to Eco-Label Demand for Fish in Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 69, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagöz, S.B. Yeşil Pazarlama ve Eko Etiketleme. Akad. Bakış 2007, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lupu, N.; Tanase, M.O.; Remus-Alexandru, T. A Straightforward X-ray on Applying the Ecolabel to The Hotel Business Area. Amfıteatru Econ. 2013, 15, 634–644. [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt, A.; Dücan, E. Eko-Etkiletlerin Turizme ve Yerel Ekonomiye Etkileri. Uluslararası Ticaret Ve Ekon. Araştırmaları 2018, 2, 68–85. [Google Scholar]

- Burgin, S.; Hardiman, N. Ecoaccreditation: Win-Win for The Environment and Small Business? Int. J. Bus. Stud. 2010, 18, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ertaş, M.; Yeşilyurt, H.; Kırlar-Can, B.; Koçak, N. Evaluation of Environmental Sensitivity of Hospitality Industry within the scope of Green Star Applications. J. Travel Hosp. Manag. 2018, 15, 102–119. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Hlee, S.; Joun, Y. Green practices of the hotel industry: Analysis through the windows of smart tourism system. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2016, 36, 1340–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaktola, K.; Jauhari, V. Exploring Consumer Attitude and Behaviour towards Green Practices in The Lodging İndustry in India. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memiş, S. Weighting Green Management Applications in Accommodation Business by Entropy Method: A Case of Giresun Province. J. Bus. Res. Turk. 2019, 11, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, L.; Dolnicar, S. Does Eco Certification Sell Tourism Services? Evidence from a Quasi-experimental Observation Study in Iceland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 24, 694–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X. Environmental Certification in Tourism and Hospitality: Progress, Process and Prospects. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Wong, S.C. Motivations for ISO 14001 in the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Tarí, J.J.; Pereira-Moliner, J.; López-Gamero, M.D.; Pertusa-Ortega, E.M. The effects of quality and environmental management on competitive advantage: A mixed methods study in the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarí, J.J.; Claver-Cortés, E.; Pereira-Moliner, J.; Molina-Azorín, J.F. Levels of quality and environmental management in the hotel industry: Their joint influence on firm performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gamero, M.D.; Claver-Cortés, E.; Molina-Azorín, J.F. Environmental perception, management, and competitive opportunity in Spanish hotels. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2011, 52, 480–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Leonidou, C.N.; Fotiadis, T.A.; Zeriti, A. Resources and capabilities as drivers of hotel environmental marketing strategy: Implications for competitive advantage and performance. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D.; Svarena, S. How “Green” are North American hotels? An exploration of low-cost adoption practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.W. Managing green marketing: Hong Kong hotel managers’ perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 442–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.J. Hotels’environmental policies and employee personal environmental beliefs: Interactions and outcomes. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, W. Environmental certification schemes: Hotel managers’ views and perceptions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 39, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzschentke, N.; Kirk, D.; Lynch, P.A. Reasons for going green in serviced accom-modation establishments. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2004, 16, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbulescu, A.; Moraru, A.D.; Duhnea, C. Ecolabelling in the Romanian Seaside Hotel Industry—Marketing Considerations, Financial Constraints, Perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.; Lin, C. An Empirical Study on Taiwanese Logistics Companies’ Attitudes toward Environmental Management Practices. Adv. Manag. Appl. Econ. 2011, 2, 223–241. [Google Scholar]

- Yücel, M.; Ekmekçiler, Ü.S. Çevre Dostu Ürün Kavramına Bütünsel Yaklaşım; Temiz Üretim Sistemi, Eko-Etiket, Yeşil Pazarlama. Elektron. Sos. Bilimler Derg. 2008, 7, 320–333. [Google Scholar]

- Kırgız, A.C. Organik Gıda Sertifikasyonlarının ve Etiketlemelerinin Türkiye Gıda Sektörü İşletmelerinin İtibarı Üzerindeki Etkisi. Sos. Bilimler Metinleri 2014, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gökdeniz, A. Konaklama Sektöründe Yeşil Yönetim Kavramı, Eko Etiket ve Yeşil Yönetim Sertifikaları ve Otellerde Yeşil Yönetim Uygulama Örnekleri. Uluslararası Sos. Ve Ekon. Bilimler Derg. 2017, 7, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, L.; Rosenthal, S. Signaling the Green Sell: The Influence of Eco-Label Source, Argument Specificity, and Product Involvement on Consumer Trust. J. Advertising. 2014, 43, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngouna, R.H.; Grabot, B. Assessing The Compliance of Product With an Eco-Label: From Standards to Constraints. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 121, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gallastegui, I.G. The Use of Eco-Labels: A Review of the Literature. Eur. Environ. 2002, 12, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougherara, D.; Combris, P. Eco-Labelled Food Products: What Are Consumers Paying For? Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2009, 36, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Grant, L.E. Eco-Labeling Strategies: The Eco-Premium Puzzle in The Wine Industry. Bus. Soc. 2014, 53, 6–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorgersen, J.; Haugaard, P.; Olesen, A. Consumer Responses to Ecolabels. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 1787–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloabal Ecolabelling Network. Global Ecolabelling Network (GEN) Information Paper: Introductıon to Ecolabelling. Available online: https://globalecolabelling.net/assets/Uploads/intro-to-ecolabelling.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Karacan, A.R. İşletmelerde Çevre Koruma Bilinci ve Yükümlülükleri, Türkiye ve Avrupa Birliğinde İşletmeler Yönünden Çevre Koruma Politikaları. Ege Akad. Bakış 2002, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, N. Sustainable Tourism. A Case Study: Klaus K Hotel Helsinki, Degree Programme in Tourism. Ph.D. Thesis, Laurea University of Applied Sciences, Vantaa, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oflaç, B.S.; Göçer, A. Genç Tüketicilerin Algılanan Çevresel Bilgi Düzeyleri ve Eko-etiketli Ürünlere Karşı Yaklaşımları Üzerine Bir Araştırma. Gazi Üniversitesi İktisadi Ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Derg. 2015, 17, 216–228. [Google Scholar]

- Laureiro, M.L.; McCluskey, J.J.; Mittelhammer, R.C. Assessing Consumer Preferences for Organic, Eco-Labeled, and Regular Apples. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2001, 26, 404–416. [Google Scholar]

- EU. EU Ecolabel Products/Services Keep Growing. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/ecolabel/facts-and-figures.html (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Kından, A. Bir Eko-Etiket Olarak Mavi Bayrak’ın Türkiye Kıyı Turizminde Bir Pazarlama Unsuru Olabilirliğinin Araştırılması, Yüksek Lisans Tezi; Ankara Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü: Ankara, Turkey, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Font, X. Regulating the Green Message: The Players in Ecolabelling. In Tourism Ecolabelling; Font, X., Buckley, R.C., Eds.; CABI Publishing: London, UK, 2001; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Duglio, S.; Ivanov, S.; Magliano, F.; Ivanova, M. Motivation, Costs and Benefits of the Adoption of The European Ecolabel in The Tourism Sector: An Exploratory Study of Italian Accommodation Establishments. Izv. J. Varna Univ. Econ. 2017, 1, 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, J.Y.; Chan, W.; Zhang, C.X. Tools for Benchmarking and Recognizing Hotels’ Green Effort-Environmental Assessment Methods and Eco-Labels. J. China Tour. Res. 2014, 10, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, H.; Atay, L. Otel İşletmelerinde Yeşil Pazarlama ve Çevre Sertifikalarının Değerlendirilmesi. Aksaray Üniversitesi İktisadi Ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Derg. 2017, 9, 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, R.A.; Lopez, A.G.; Caballero, J.L.J. Has Implementing an Ecolabel Increased Sustainable Tourism in Barcelona? Cuad. De Tur. 2017, 40, 93–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Sanabria, R.; Skinner, E. Sustainable Tourism and Ecotourism Certification: Raising Standards and Benefits. J. Ecotourism 2003, 2, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, V.; Sirakaya, E.; Kerstetter, D. Developing Countries and Tourism Ecolabels. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üngüren, E.; Çevirgen, A. Alanya’daki Konaklama İşletmelerinin Genel Yapısının Analizi. Uluslararası Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi 2016, 9, 2223–2236. [Google Scholar]

- Türkiye Otelciler Birliği. 2018 Yılı İşletme (Bakanlık) Belgeli Tesisler Konaklama İstatistikleri. Available online: http://www.turob.com/tr/istatistikler (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- T.C. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı. İşletme ve Yatirim Belgeli Tesis İstatistikleri. Available online: http://yigm.kulturturizm.gov.tr/Eklenti/53370,isletme-ve-yatirim-belgeli-tesis-istatistikleri-2016xls-.xlsx?0 (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- Kirk, D. Attitudes to environmental management held by a group of hotel managers in Edinburgh. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1998, 17, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezan, O.; Raab, C.; Yoo, M.; Love, C. Sustainable hotel practices andnationality: The impact on guest satisfaction and guest intention to return. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claver-Cortés, E.; Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Pereira-Moliner, J.; López-Gamero, M.D. Environmental strategies and their impact on hotel performance. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbasera, M.; Du Plessis, E.; Saayman, M.; Kruger, M. Environmentally-friendly practices in hotels. Acta Commer. 2016, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; MCGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ceylan, Z.; Gürsev, S.; Bulkan, S. İki Aşamalı Kümeleme Analizi ile Bireysel Emeklilik Sektöründe Müşteri Profilinin Değerlendirilmesi. Bilişim Teknolojileri Dergisi 2017, 10, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Unguren, E.; Dogan, H. Beş Yıldızlı Konaklama İşletmelerinde Çalışanların İş Tatmin Düzeylerinin Chaid Analiz Yöntemiyle Değerlendirilmesi. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi 2010, 11, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Unguren, A. Investigation of Fatalistic Beliefs and Experiences Regarding Occupational Accidents among Five Stars Accommodation Companies Employees. Tour. Acad. J. 2018, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan, N.; Baris, E. Environmental protection programs and conservation practices of hotels in Ankara, Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F. Investigating structural relationships between service quality, perceived value, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for air passengers: Evidence from Taiwan. Transp. Res. A Policy Pract. 2008, 42, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Hsu, L.T.; Han, H.; Kim, Y. Understanding how consumers view green hotels: How a hotel’s green image can influence behavioural intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.W. Green marketing: Hotel customers’ perspective. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 915–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D. What drives companies to seek ISO 14000 certification? Pollut. Eng. Int. 1999, 1, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel, P.L. Can the ISO 14000 series environmental management standards provide a viable alternative to government regulation? Am. Bus. Law J. 2000, 37, 237–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, D. Environmental Management in Hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 1995, 7, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enz, C.A.; Siguaw, J.A. Best hotel environmental practices. Cornell Hotel Rest. A. Q. 1999, 40, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Benito, J.; González-Benito, Ó. Environmental proactivity and business performance: An empirical analysis. Omega 2005, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Toffel, M.W. Organizational responses to environmental demands: Opening the black box. Strategıc Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1027–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, T.H.; Hoover, L.C.; Revilla, G. Environmental tactics used by hotel companies in Mexico. Int. J. Hospit. Tour. Admin. 2001, 1, 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, M.; Darnton, G. Green Companies or Green Con-panies: Are Companies Really Green, or Are They Pretending to Be? Bus. Soc. Rev. 2005, 110, 117–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A. Green hotels: A fad, ploy or fact of life? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, N.J.; Fong, C.M. Green product quality, green corporate image, green customer satisfaction, and green customer loyalty. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 2836–2844. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C.E.; Lorente, C.J.; Jiménez, D.B.J. Environmental Strategies in Spanish Hotels: Contextual Factors and Performance. Serv. Ind. J. 2004, 24, 101–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, M.J.A.; Jimenez, J.B.; Lorente, J.J.C. An Analysis of Environmental Management, Organizational Context and Performance of Spanish Hotels. Omega 2001, 29, 457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Mercan, Ş.O. Lisans Düzeyinde Turizm Eğitimi Alan Öğrencilerin Otel İşletmelerini Çevre Duyarlılığı Açısından Değerlendirmeleri. Karabük Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 2016, 6, 126–144. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Y.H.; Wu, C.T.; Wang, T.M. Attitude towards Green Hotel by Hoteliers and Travel Agency Managers in Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 1091–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, E.; Güneş, G. Sürdürülebilir Turizm ve Konaklama İşletmeleri için Yeşil Anahtar Eko-Etiketi, 1; Uluslararası Türk Dünyası Turizm Sempozyumu Bildiri Kitabı: Kastamonu, Turkey, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Akova, O.; Yaşar, A.G.; Aslan, A.; Çetin, G. Çalışanların Çevre Yönetimi Algıları ve Örgüt Kültürü İlişkisi: Yeşil Yıldızlı Otellere Yönelik Bir Araştırma. Res. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 2, 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- El Dief, M.; Font, X. The determinants of hotels’ marketing managers’ green marketing behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, B.S.; Yumuk, Y. Türk Turizm Pazarında Çevreye Duyarlı Bir Eğilim: Yeşil Yıldız Uygulaması Ve Yeşil Yıldız Sahibi Otel İşletmeleri Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme, 14; Ulusal turizm Kongresi Bildiriler Kitabı: Kayseri, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Robinot, E.; Giannelloni, J.L. Do hotels’ green attributes contribute tocustomer satisfaction? J. Serv. Mark. 2010, 24, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A. Implementing Sustainability in Service Operations at Scandic Hotels. Interfaces 2000, 30, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slevitch, L.; Mathe, K.; Karpova, E.; Scott-Halsell, S. “Green” attributes andcustomer satisfaction: Optimization of resource allocation and performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 802–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atay, L.; Dilek, S.E. Konaklama İşletmelerinde Yeşil Pazarlama Uygulamaları: Ibis Otel Örneği. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi 2013, 18, 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Peiró-Signes, A.; Segarra-Oña, M.D.V.; Verma, R.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.; Vargas-Vargas, M. The impact of environmental certification on hotel guest ratings. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S. Barriers to EMS in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, E.C.; Azorin, J.M.; Moliner, J.P. Competitiveness Inmass Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Cladera, M. Repeat visitation in mature sun and sand holiday destinations. J. Travel Res. 2006, 44, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheodorou, A. Exploring the evolution of tourism resorts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martin, J.D. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.W.; Ponsford, I.F. Confronting tourism’s environmental paradox: Transitioning for sustainable tourism. Futures 2009, 41, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A.L.; Beeton, R.J. Sustainable tourism or maintainable tourism: Managing resources for more than average outcomes. J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparon, M.; Gyuris, E.; Stoeckl, N. Does ECO certification deliver benefits? An empirical investigation of visitors’ perceptions of the importance of ECO certification’s attributes and of operators’ performance. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.C.; Waliczek, T.M.; Zajicek, J.M. Relationship between Environmental Knowledge and Environmental Attitude of High School Students. J. Environ. Educ. 1999, 30, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, M. İşletme Yöneticilerinin Çevre Duyarlılığı Ve Farkındalık Düzeylerinin Belirlenmesi. MANAS J. Soc. Stud. 2017, 6, 359–374. [Google Scholar]

- Küçük, M. Konaklama İşletmeleri Ve Çevre Duyarlı Uygulamalar. 14; Ulusal Turizm Kongresi Bildiriler Kitabı: Kayseri, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, E.S.; Hon, A.H.; Chan, W.; Okumus, F. What drives employees’ intentions to implement green practices in hotels? The role of knowledge, awareness, concern and ecological behaviour. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Hawkins, R. Attitude towards EMSs in an international hotel: An exploratory case study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P. European hoteliers’ environmental attitudes: Greening the business. Cornell Hotel Rest. A Q. 2005, 46, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potoski, M.; Aseem, P. Covenants with weak swords: ISO 14001 and facilities’ environmental performance. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2005, 4, 745–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, L.; Garcıa, J. Does ISO 9000 certification affect consumer perceptions of the service provider? Manag. Serv. Qual. 2009, 19, 140–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, D.; Yılmaz, İ. Otel İşletmelerinde Yeşil Pazarlama Uygulamaları: Nevşehir Örneği, Nevşehir: Nevşehir Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi, 13; Ulusal Pazarlama Kongresi: Nevşehir, Turkey, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Giritlioğlu, İ.; Güzel, M.O. Green-star Practıces in Hotel Enterprises: A Case Study in the Gazıantep and Hatay Regıons. J. Int. Soc. Res. 2015, 8, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification of Hotel | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 5 Star (n = 166) | 4 Star (n = 44) | 3 Star (n = 88) | Other Hotel (n = 110) | Total |

| Female | 15.7% | 25.0% | 34.1% | 34.5% | 25.7% |

| Male | 84.3% | 75.0% | 65.9% | 65.5% | 74.3% |

| Age | 5 Star | 4 Star | 3 Star | Other Hotel | Total |

| 27–33 Years | 13.9% | 15.9% | 14.8% | 10.0% | 13.2% |

| 34–40 years | 60.8% | 52.3% | 55.7% | 61.8% | 59.1% |

| 41–47 years | 22.3% | 29.5% | 28.4% | 26.4% | 25.5% |

| 48 years and older | 3.0% | 2.3% | 1.1% | 1.8% | 2.2% |

| Education | 5 Star | 4 Star | 3 Star | Other Hotel | Total |

| Primary education | 1.8% | 15.9% | 23.9% | 25.5% | 14.5% |

| High school | 24.1% | 40.9% | 60.2% | 43.6% | 39.0% |

| Bachelor | 74.1% | 43.2% | 15.9% | 30.9% | 46.6% |

| Department | 5 Star | 4 Star | 3 Star | Other Hotel | Total |

| Sales and Marketing manager | 17.5% | 6.8% | 1.1% | 8.2% | 10.3% |

| Front office manager | 29.5% | 13.6% | 6.8% | 13.6% | 18.6% |

| General manager | 15.7% | 6.8% | 2.3% | 1.8% | 8.1% |

| Human resources Manager | 12.7% | 18.2% | 6.8% | 10.9% | 11.5% |

| Housekeeping manager | 4.8% | 15.9% | 35.2% | 26.4% | 18.4% |

| Food and beverage manager | 12.0% | 22.7% | 30.7% | 23.6% | 20.3% |

| Kitchen manager | 7.8% | 15.9% | 17.0% | 15.5% | 12.7% |

| Type of hotel activity | 5 Star | 4 Star | 3 Star | Other Hotel | Total |

| Seasonal | 50.0% | 79.5% | 89.8% | 72.7% | 67.9% |

| All year | 50.0% | 20.5% | 10.2% | 27.3% | 32.1% |

| Eco-label ownership status of the hotel | 5 Star | 4 Star | 3 Star | Other Hotel | Total |

| Yes | 88.0% | 38.6% | 2.3% | 26.4% | 47.5% |

| No | 12.0% | 61.4% | 97.7% | 73.6% | 52.5% |

| Mean | Factor Loadings | Eigenvalues | The Ratio of Variance | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application Dost and Difficulty | 2.56 | 5331 | 15.733 | 0.901 | |

| Getting the eco-label system is costly | 2.38 | −0.906 | |||

| Service offerings of hotels with an eco-label system are more costly than hotels without an eco-label system | 2.91 | −0.875 | |||

| Getting the eco-label system is laborious | 2.34 | −0.872 | |||

| Performing eco-label procedures are exhausting | 2.40 | −0.870 | |||

| It is very difficult for the hotel to ensure both profitability and protect the environment at the same time | 2.79 | −0.842 | |||

| Eco-labeling in hotels can only be fully implemented when operating costs are reduced | 2.73 | −0.830 | |||

| Employee Engagement and Environmental Awareness | 3.61 | 3991 | 11.778 | 0.898 | |

| Eco-labeling provides environmental awareness to employees | 3.95 | 0.879 | |||

| Eco-labeling increases employee satisfaction | 3.39 | 0.869 | |||

| Eco-labeling increases employee loyalty to the company | 3.31 | 0.861 | |||

| Eco-labeling enables managers to display environmentally sensitive management | 3.64 | 0.765 | |||

| Eco-labeling increases the sensitivity of managers to the environment | 3.77 | 0.702 | |||

| Benefit of Profitability and Competitive Advantage | 3.58 | 3839 | 11.330 | 0.937 | |

| Eco-labeling increases business profitability | 3.84 | 0.869 | |||

| Eco-labeling increases occupancy rates | 3.49 | 0.841 | |||

| Eco-labeling provides competitive advantage | 3.58 | 0.832 | |||

| Eco-labeling gives to hotels bargaining power against tour operators | 3.42 | 0.781 | |||

| Reduction of Operating Costs | 3.54 | 3516 | 10.376 | 0.877 | |

| Eco-label applications reduce costs | 3.61 | 0.851 | |||

| Eco-label applications increase operating costs | 2.58 | −0.841 | |||

| Eco-label applications reduce energy costs | 3.58 | 0.807 | |||

| Eco-label applications reduce water costs | 3.57 | 0.801 | |||

| Contribution to Business Reputation | 3.43 | 3097 | 9.140 | 0.891 | |

| Eco-labeling increases the social reputation of hotels | 3.53 | 0.878 | |||

| Hotels with an eco-label are the businesses that employees want to work in as a priority | 3.44 | 0.860 | |||

| Hotels with eco-label are the businesses that tour operators want to work primarily | 3.86 | 0.801 | |||

| Hotels with eco-label are priority preference of suppliers | 2.88 | 0.766 | |||

| Ensuring Sustainable Management Awareness | 3.95 | 2601 | 7.676 | 0.899 | |

| Eco-labeling significantly contributes to the sustainable management of hotels | 4.00 | 0.864 | |||

| Eco-label systems severely reduce the negative effects of hotels on the environment | 4.00 | 0.861 | |||

| Eco-label systems contribute significantly to the institutionalization of hotels | 3.84 | 0.0743 | |||

| Customer Satisfaction Impact | 3.25 | 1988 | 5.867 | 0.851 | |

| Eco-labelling increases customer satisfaction | 3.24 | 0.801 | |||

| Eco-labelling increases customer loyalty | 3.25 | 0.711 | |||

| The necessity of dissemination of eco-labels | 3.79 | 1814 | 5.354 | 0.737 | |

| Eco-labels should be mandatory at all hotels | 3.85 | 0.891 | |||

| The government should support the dissemination of eco-label systems in hotels | 4.24 | 0.556 | |||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.921 | ||||

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | 17,396.518 (df: 435) p = 0.00 | ||||

| The Ratio of Total Variance | 77.254% | ||||

| Overall Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.840 | ||||

| Clusters | SD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 n = 78 (%19) | 2 n = 117 (%29) | 3 n = 213 (%52) | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Application Cost and Difficulty | Mean | 3.87 | 3.24 | 1.77 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.22 |

| Employee Engagement and Environmental Awareness | Mean | 2.17 | 3.19 | 4.38 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

| Benefit of Profitability and Competitive Advantage | Mean | 2.36 | 3.27 | 4.20 | 0.51 | 0.26 | 0.30 |

| Reduction of Operating Costs | Mean | 2.37 | 3.24 | 4.14 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.27 |

| Contribution to Business Reputation | Mean | 2.30 | 3.07 | 4.04 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.22 |

| Ensuring Sustainable Management Awareness | Mean | 2.44 | 3.57 | 4.70 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.28 |

| Customer Satisfaction Impact | Mean | 1.87 | 3.07 | 3.85 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.36 |

| The necessity of dissemination of Eco-Labels | Mean | 3.34 | 3.19 | 4.77 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.38 |

| Sustainable Management Policies | Yes | No | t | p |

| n = 194 | n = 214 | |||

| 1. Policies to reduce negative impacts on your business environment | 3.73 | 2.31 | 26.539 | 0.000 * |

| 2. Policies to support the local economy | 3.76 | 1.96 | 38.09 | 0.000 * |

| 3. Policies to protect local culture and traditions | 3.81 | 1.80 | 38.762 | 0.000 * |

| 4. Occupational health and safety policies | 4.40 | 3.54 | 17.241 | 0.000 * |

| Training and Information Activities | Yes | No | t | p |

| n = 194 | n = 214 | |||

| 5. Training employees on environmental issues | 4.54 | 1.95 | 59.29 | 0.000 * |

| 6. Occupational health and safety trainings | 4.64 | 2.97 | 29.211 | 0.000 * |

| 7. Informing all employees of the hotel’s initiatives on environmental issues | 3.26 | 1.87 | 27.227 | 0.000 * |

| Energy and Water Saving Management | Yes | No | t | p |

| n = 194 | n = 214 | |||

| 8. Energy saving applications in customer rooms and common areas of hotel | 4.89 | 4.28 | 14.071 | 0.000 * |

| 9. Recording all energy consumption in monthly form | 4.95 | 4.93 | 0.594 | 0.553 |

| 10. Informing customers about energy savings | 4.70 | 3.92 | 16.392 | 0.000 * |

| 11. Water saving applications in customer rooms and common areas of hotel | 4.74 | 4.21 | 12.849 | 0.000 * |

| 12. Recording all water consumption in monthly form | 4.97 | 4.92 | 2.128 | 0,034 * |

| 13. Informing customers about water savings | 4.69 | 4.00 | 16.931 | 0.000 * |

| Environmental Waste Management | Yes | No | t | p |

| n = 194 | n = 214 | |||

| 14. Collection of wastes by category | 4.52 | 2.05 | 42.194 | 0.000 * |

| 15. Recording the amount of waste food on a daily basis | 4.35 | 1.53 | 51.592 | 0.000 * |

| Employees Oriented Applications | Yes | No | t | p |

| n = 194 | n = 214 | |||

| 16. Payment of overtime fees | 4.94 | 4.83 | 3.57 | 0.000 * |

| 17. Implementation of the personnel discipline regulation | 4.00 | 1.56 | 41.565 | 0.000 * |

| 18. Giving orientation training before starting work | 4.12 | 1.73 | 39.068 | 0.000 * |

| 19. Applications of employee suggestion and complaint | 3.43 | 1.79 | 25.989 | 0.000 * |

| 20. Rewarding of environmentally friendly employees | 223 | 1.03 | 35.926 | 0.000 * |

| Informing Customers | Yes | No | t | p |

| n = 194 | n = 214 | |||

| 21. No negative impact on local community access to resources | 4.53 | 4.52 | 0.152 | 0.879 |

| 22. Informing customers about local people and local culture | 3.15 | 2.06 | 15.507 | 0.000 * |

| 23. Consideration of the opinions of the local community and the employees on the construction of new investments | 1.59 | 1.58 | 0.273 | 0.785 |

| 24. Introducing our sustainability programs to customers | 4.58 | 1.28 | 70.607 | 0.000 * |

| 25. Informing our customers that we are environmentally friendly | 4.88 | 1.96 | 52.917 | 0.000* |

| 26. Giving information about local traditions, culture, dress, natural and cultural heritage to customers | 4.21 | 2.51 | 36.008 | 0.000 * |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yılmaz, Y.; Üngüren, E.; Kaçmaz, Y.Y. Determination of Managers’ Attitudes Towards Eco-Labeling Applied in the Context of Sustainable Tourism and Evaluation of the Effects of Eco-Labeling on Accommodation Enterprises. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11185069

Yılmaz Y, Üngüren E, Kaçmaz YY. Determination of Managers’ Attitudes Towards Eco-Labeling Applied in the Context of Sustainable Tourism and Evaluation of the Effects of Eco-Labeling on Accommodation Enterprises. Sustainability. 2019; 11(18):5069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11185069

Chicago/Turabian StyleYılmaz, Yusuf, Engin Üngüren, and Yaşar Yiğit Kaçmaz. 2019. "Determination of Managers’ Attitudes Towards Eco-Labeling Applied in the Context of Sustainable Tourism and Evaluation of the Effects of Eco-Labeling on Accommodation Enterprises" Sustainability 11, no. 18: 5069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11185069

APA StyleYılmaz, Y., Üngüren, E., & Kaçmaz, Y. Y. (2019). Determination of Managers’ Attitudes Towards Eco-Labeling Applied in the Context of Sustainable Tourism and Evaluation of the Effects of Eco-Labeling on Accommodation Enterprises. Sustainability, 11(18), 5069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11185069