1. Introduction

According to a McKinsey report [

1], in the coming years, Vietnam will need to improve its overall labor productivity growth by more than 50 percent if the economy is to meet the government’s target of 7 to 8 percent annual growth by 2020. Failing this, the country’s growth is likely to decline to between 4.5 and 5 percent. For the past few decades, the Southeast Asian country has enjoyed significant benefits from structural transformation (in particular, the labor force’s transition away from agriculture). However, McKinsey [

1] also points out that this instrument of economic growth will soon lose its effectiveness. As such, Vietnam needs to find other ways of increasing its productivity performance.

Like many developing countries, Vietnam has prioritized its education system as a means of providing skilled workers. In particular, the return on schooling as a central policy parameter has been studied and estimated by several researchers, especially since the market reforms in the 1990s [

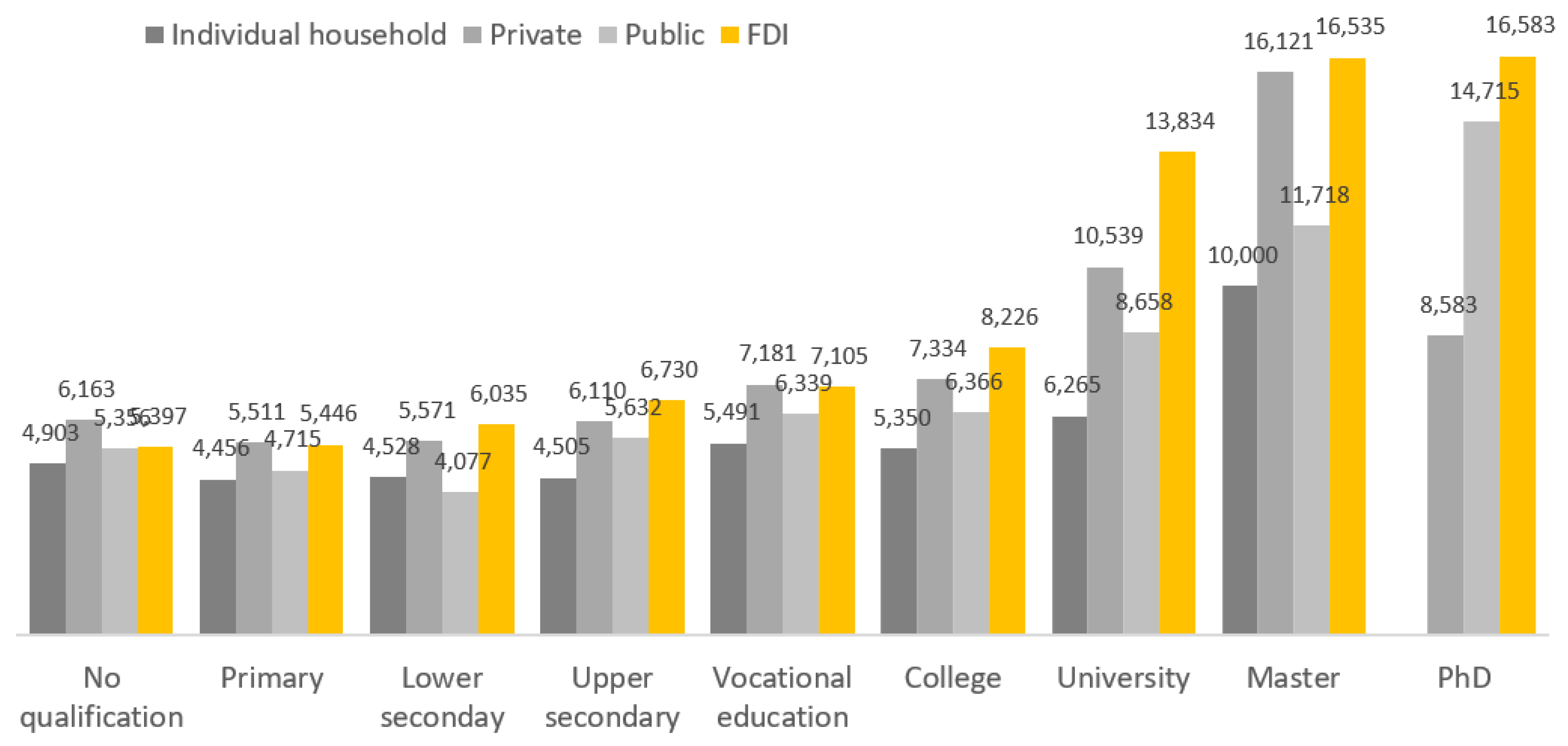

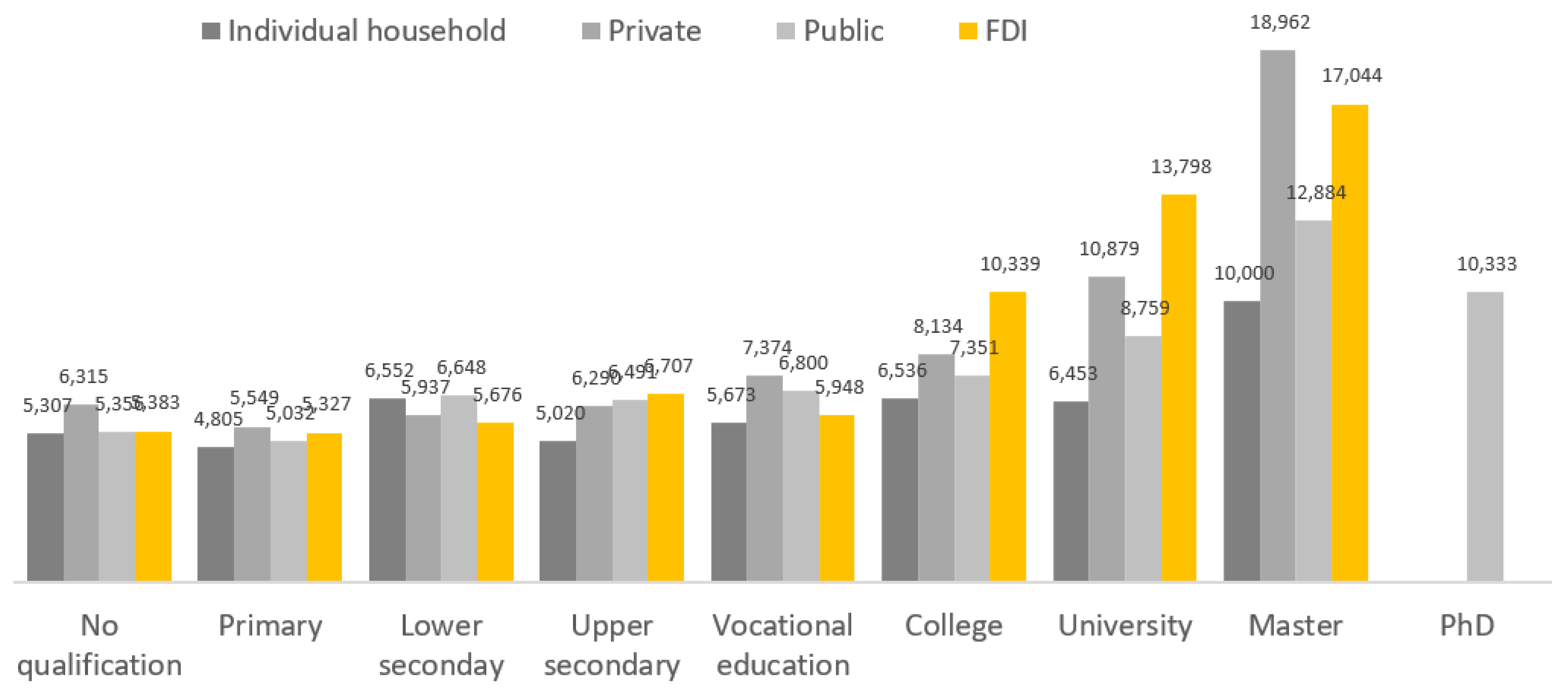

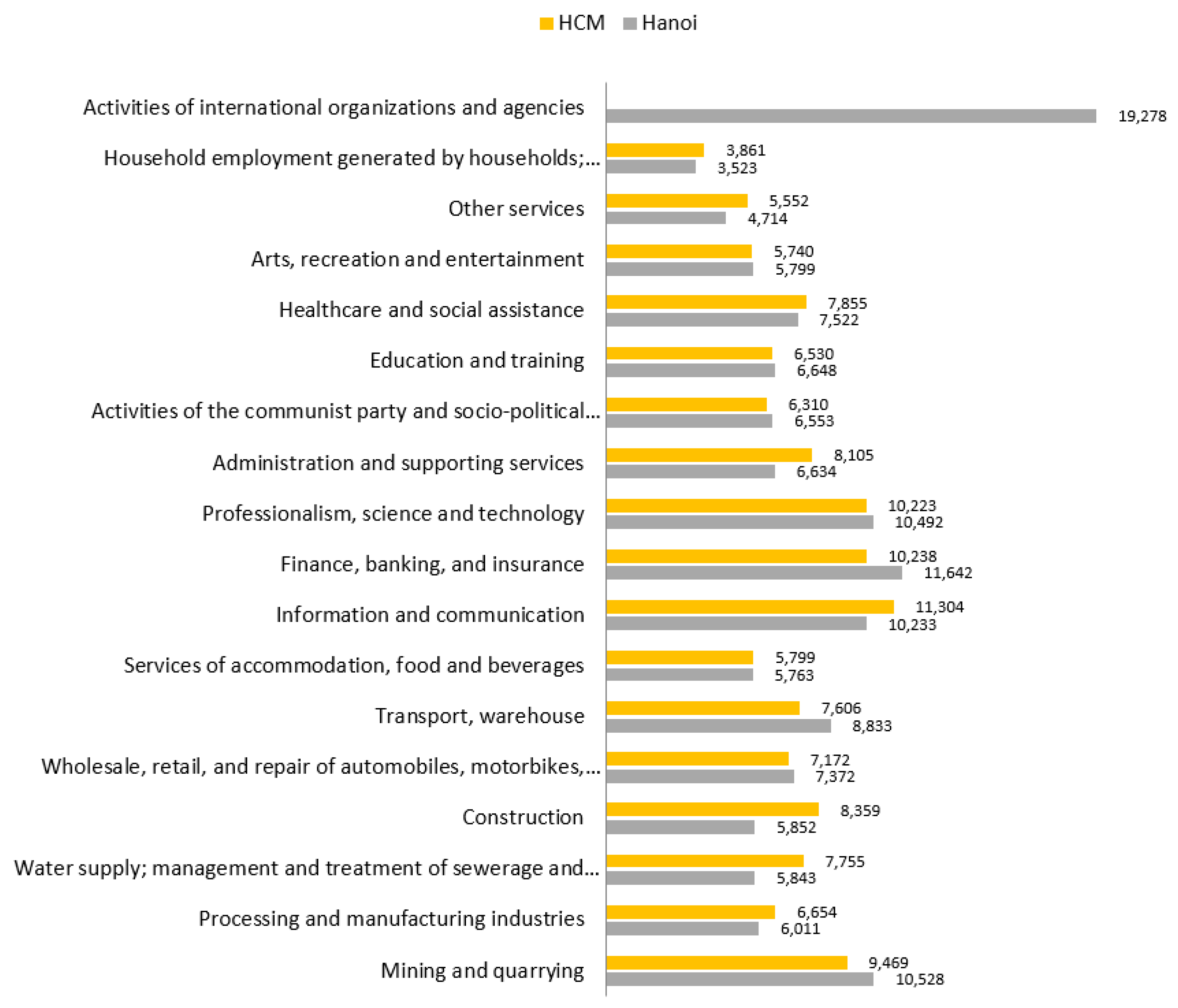

2]. This study also aims to identify the wage earnings attributable to education in Vietnam. However, we focus on the country’s two most significant economic hubs (Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC)) using data from the 2016 Vietnam Household Living Standard Survey.

Previous studies on the return on education in Vietnam have all focused on the country level. Although this is often the case for studies of this kind, several studies have investigated individuals’ income heterogeneity, rather than regional disparities, including studies on Sweden [

3], China [

4], Brazil [

5], and Poland [

6]. These studies are based on the theory of new economic geography, which suggests that regional competitiveness is closely related to economic geography and the regional economy. Their empirical findings all confirm differences in the returns on education between regions within the same country. What causes these differences? According to Roback [

7,

8], who studies data from the 98 largest US cities, persistent regional wage differences can be explained largely by local attributes, particularly quality of life and amenities (e.g., infrastructure, pollution levels, and climate and other natural endowments). Furthermore, Hanushek and Kim [

9] assert that the “quality” of the labor force can explain differential economic growth within regions. Conducted at the country level for 150 nations, the latter study uses cognitive skills in mathematics and science (through comparative tests for children) as a measure of labor quality, emphasizing the importance of investing in education and training. Finally, with the rise of creativity as a fundamental economic force, vibrant communities built on a “people climate” have become locations that attract companies and better quality labor. This is especially true of the “creative class”, a new socioeconomic class identified by American economist Richard Florida that can spur regional economic growth through innovation [

10].

Hanoi and HCMC are often compared in a similar way to Beijing and Shanghai, Madrid and Barcelona, and Sydney and Melbourne [

11]. Undoubtedly, both have been driving forces behind the dramatic economic growth in Vietnam. In addition, the two cities have the highest concentration of colleges and universities in terms of both number and quality [

12] and are the leading destinations for migrant workers. Owing to their significant roles in the development of Vietnam, the two cities have been studied separately and compared with the rest of the country. However, until 40 years ago, the country was divided into Northern Vietnam (with Hanoi as its capital) and Southern Vietnam (with HCMC, Saigon at the time, as its capital). Thus, each city possesses its own characteristics, culture, and business environment, all of which can potentially influence the labor market.

As a result, estimating and understanding the differences in the return on schooling in Hanoi and HCMC requires understanding the circumstances in each case, which might differ from the overall picture of the country.

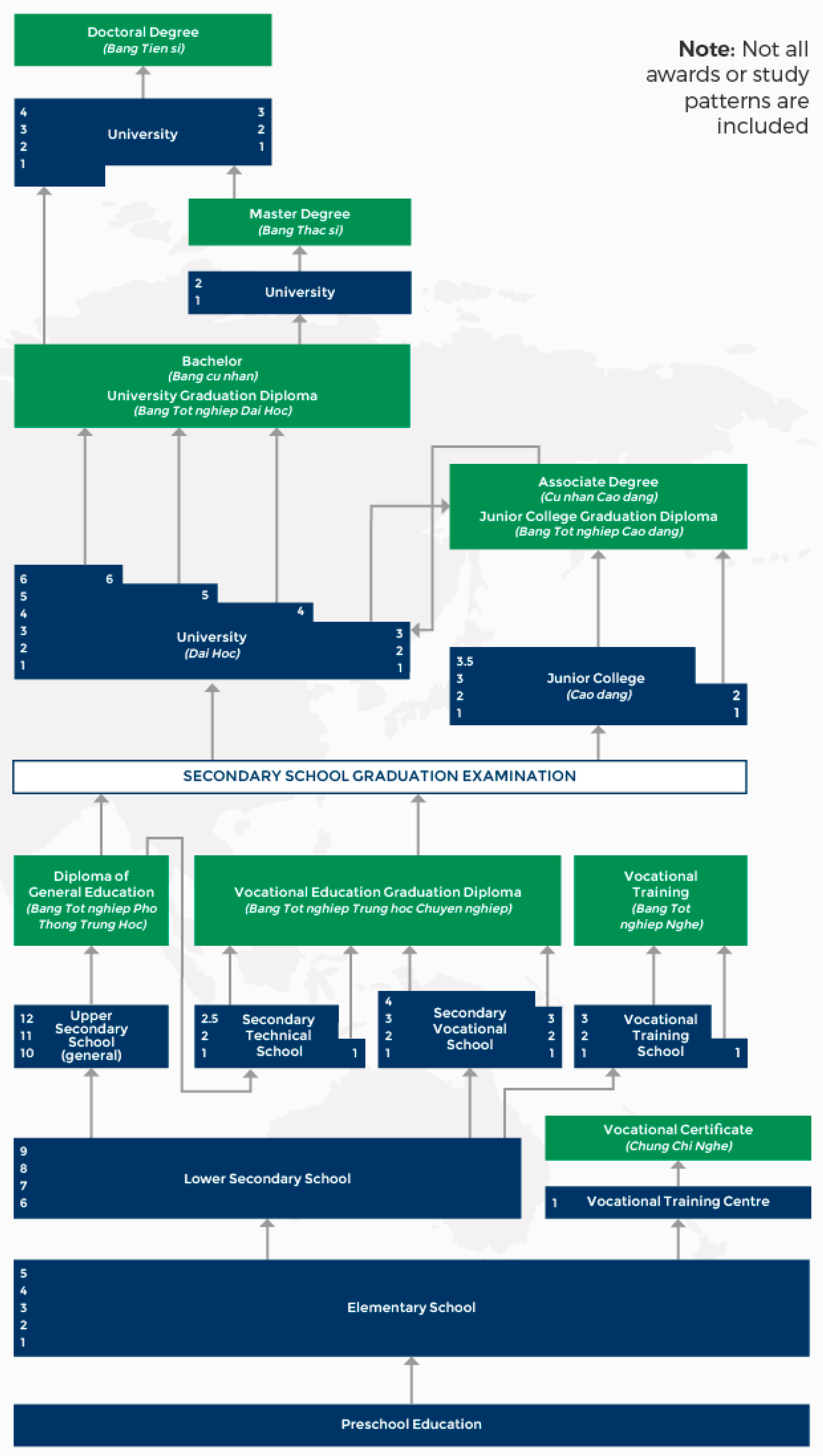

Figure A1 describes the overall education system in Vietnam. Moreover, as in many developing countries, there is much provincial variation, even within the same region. Hence, it is important that we focus on the provincial level [

13]. Therefore, the second purpose of this study is to suggest ways in which to provide a better framework for education, training, and labor in each city.

Our empirical results reveal that Vietnam should promote vocational education and develop a more open, flexible system that is less dependent on credential hiring, especially in the public sector, to achieve sustainable productivity and economic growth. This finding is consistent with that of a study documenting the importance of higher education to economic growth in China [

14]. Given these findings, we argue that to maintain its sustainable productivity growth, Vietnam needs to upgrade its education system. We also point out a flaw in Vietnam’s labor market efficiency, which stems from the country’s cultural roots, overemphasizing education and credentials. This emphasis is somewhat old-fashioned, given the rise of the creative industry and the freelance generation. Furthermore, it is severely inefficient, given the low quality of education in Vietnam. This issue is sensitive because, for a long time, an important topic of discussion among Vietnamese people (that has never officially been studied or documented) is that Vietnamese society (i.e., Northern Vietnam, or Hanoi, more so than Southern Vietnam, or HCMC) remains overly conservative, status-driven, and inflexible. In the public sector, the capacity limitations, lack of effort toward making changes, and conservative thinking with regard to labor recruitment are even more emphasized. (We implicitly assume that the location choice between Hanoi and HCMC is largely exogenous, because the two cities are characterized differently in Vietnam. For example, Hanoi is the center of politics in the nation, whereas HCMC is an economic hub. Hence, as in the model of Lucas [

15] on economic development, we regard Hanoi and HCMC as two individual economies).

1.1. Hanoi and HCMC: The Tale of Two Cities

For the past century, Vietnam has witnessed a tale of two cities. Hanoi is the capital and a long-time political, economic, and cultural center, whereas HCMC is the largest city in terms of population and is the leading economic, social, and technological hub of the country. In terms of economic significance, the two cities are by far the largest contributors to the state budget revenue, with HCMC contributing 15.32 billion

$ in 2017, outperforming all other cities and provinces in the country [

16]. As a developing economy with a rapid urbanization rate, Vietnam also suffers from a widening gap between urban and rural poverty. Large hubs, such as Hanoi and HCMC, that offer better wages, education, and overall lifestyle attract a significant number of migrants who have moved away from their rural homes to the cities. According to the 2015 National Internal Migration Survey, migrants account for 16.3% and 20.7% of those aged 15–59 living in Hanoi and HCMC, respectively, which are both higher than the national average. Most migrants seek employment, with the majority of the rest migrating for education. Migrants also tend to marry later and have a higher level of education (professional/technical qualifications or college/university) than non-migrants. These factors all have a considerable impact on education, health care services, and employment in migrant destinations, especially in regions with a high level of young migrants, such as the Red River Delta and Hanoi.

After the fall of Saigon in 1975, Vietnam was formally reunified. Peace was restored, and the country began to develop. Nevertheless, differences in natural endowments and history have helped establish certain distinguishing characteristics (even stereotypes) of Northerners and Southerners, represented by Hanoi and HCMC, respectively. Hanoi is the capital and has a long history, rich culture, and extreme cold and hot seasons. As such, it is somewhat more traditional, cultured, formal, and introverted. In contrast, the younger HCMC is an international port with a tendency toward openness and has a more favorable climate. Hence, it is much more dynamic, vibrant, and casual. These differences in history and culture have shaped a contrasting mindset in Vietnam’s two largest cities when it comes to business. Home to the ruling elite for many years, Hanoi has a hierarchical society in which strong political connections tend to carry much weight [

17]. Owing to its development path and position as the capital, Hanoi also has more state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which might reinforce this tendency. In contrast, HCMC has always been a welcoming destination for traders and entrepreneurs. Therefore, it tends to be more “fluid, multicultural, and outward-looking” than the capital [

17]. An online article on start-ups in Hanoi and HCMC sums up the business subcultures in the two cities: Hanoi has more qualified engineers who, in general, are also more talented; HCMC has better business-minded entrepreneurs [

18]. As a result, for the past decade, Hanoi has been trying to refresh and rebrand its image as a more open, nurturing place for talent. However, differences remain. Taken together, we predict that Hanoi is more rewarding for people who have a better education. In contrast, the flexible and fast-moving culture in HCMC might be more responsive to factors other than qualifications, such as experience. Therefore, we explore the return on schooling in these two cities, comparing them with each other and with the country as a whole, based on the findings of previous studies.

1.2. Scope and Structure

We use data from the Vietnam Household Living Standard Survey conducted by the General Statistics Office of Vietnam to estimate the return on schooling in Hanoi and HCMC. Note that other unobservable factors, such as the role of labor unions, efficiency wage, school quality, and so on, are beyond the scope of this study.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature on human capital theory and discusses returns on schooling from both an international perspective and in relation to Vietnam.

Section 3 discusses our data and methodology, and

Section 4 presents our descriptive and econometric findings. Lastly,

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

Many studies have examined returns on schooling for various geographic locations and periods, finding a positive correlation between education and the level of success of individuals in the labor market. That is, better-educated people are more likely to find better jobs and enjoy higher wages and are less likely to suffer from unemployment [

19]. Studies such as those of Psacharopoulos [

20,

21,

22] show a relatively consistent pattern around the world over time. More recently, an ambitious study assembled empirical findings from 139 countries and 819 household surveys, all with comparable estimates, databases based on the same specifications, estimation procedures, and so on [

23]. These results reinforce the findings of previous studies. That is, private returns on schooling are positive, in general, but decline as investment in education increases. In addition, women receive a greater reward for higher education than men do, and the estimated return on education seems to be higher in low- and middle-income countries. However, a study that targets developing countries [

24] finds no evidence that the returns on schooling in these countries are systematically higher than those in developed economies. In contrast to the findings of older studies, recent studies find that, globally, private returns on tertiary education are now highest, followed by returns on primary and secondary schooling [

25]. This is mostly because primary school attendance has become compulsory in many countries. These studies show that returns on schooling cannot be measured by a single parameter because they are influenced by various characteristics and background of an individual [

19]. This point is discussed in greater detail in the following section.

2.1. Mincer Equation

How to accurately measure the causal effect of education on earnings is the source of much debate. Nevertheless, many studies on earnings attributable to education adopt Mincer’s classic earnings function [

26], which models the natural logarithm of an individual’s earnings as a function of completed school years and experience, as follows:

where w denotes an individual’s earnings, S denotes an individual’s years of schooling, X denotes an individual’s years of experience, and ε is a disturbance term representing other unobserved factors that determine wages but cannot be measured.

The use of the log transformation serves several purposes. First, it allows us to interpret the result as a percentage term. Moreover, the distribution of log earnings is very close to a normal distribution and helps exclude negative earnings values (i.e., when individuals receive “income” in the form of a government subsidy and do not pay tax) [

27]. However, this issue is not really a concern here. Furthermore, various studies use different earnings measures (annual, weekly, hourly).

The Mincer equation depicts a linear relationship between education and earnings; that is, each additional year spent in school increases wages in a linear, constant, and proportional manner throughout the year. However, this relationship does not always hold. In addition, this measure has flaws when adopted for countries where students can follow different school tracks and, thus, cannot be grouped into one years-of-schooling unit. For example, depending on their plans, students may attend a college or vocational school or might begin working after leaving high school [

19]. As a result, more recent studies prefer to use dummy variables for the completed education level as an alternative measure of education. The reasoning behind this approach is called the “sheepskin effect” [

28,

29], which hypothesizes that obtaining a degree is more rewarding than spending the same amount of time at school without earning a certificate. Thus, surveys now ask for the degrees that people have acquired in addition to the number of years of school they have completed. Nevertheless, Harmon et al. [

30] show that the assumption of a linear return on schooling, despite being a strong assumption, is “remarkably hard to reject.” Therefore, in this study, we use both methods to measure education in our regressions.

Lastly, a quadratic measure of experience is used to express the concave relationship between age and earnings. In other words, the benefits of education may vary with age groups. Typically, the benefits increase relatively quickly at the beginning of a person’s career, but then slow down, and even decrease as he/she approaches retirement [

31]. Since it is difficult to obtain accurate information on a person’s relevant experience, most studies construct a “potential experience” variable (as proposed by Mincer). This variable is typically equal to an individual’s age minus the number of completed years of schooling minus six: X = A − S − 6 (assuming that he/she starts school at the age of six and begins to work immediately after graduation).

However, the Mincer equation has been criticized, particularly for its potential for bias. Nevertheless, the human-capital earnings function has provided a framework for most studies on returns on education, owing to its ease of use, simplicity, and intuitive appeal. In fact, several works [

23,

32] have examined the results from various studies, and note that the basic Mincerian model is more stable than may have been expected. Next, we discuss some of the most debated issues, followed by ways in which these limitations can be overcome within the constraints of this study.

2.2. Extended Mincer Equation

2.2.1. Ability Bias

One of the most discussed drawbacks of the Mincer equation is the extent to which schooling is endogenous, owing to people’s unobserved abilities [

33]. Economists realized that ability and schooling are likely to be correlated (most likely positively), and if ability affects earnings, the estimated return on education will potentially be upward biased [

34]. In other words, higher earnings might mistakenly be credited to a higher level of education when, in fact, they are the result of greater abilities. Individuals with superior abilities are more likely to do well in job interviews and, in general, perform better in their jobs (and, hence, have higher earning outcomes). However, this finding is not necessarily because they have a higher level of education.

Several approaches have been proposed to tackle this issue. One option is to include a proxy variable that represents inherent ability. For example, IQ test results [

35,

36,

37] are thought to be strong predictors of education [

32]. However, indicators of ability are, in general, not perfect, and are not always present in regular data sets. Another approach is to use data on twins and siblings [

38,

39,

40,

41] who share the same family conditions and, sometimes, abilities in order to eliminate any omitted-ability bias. After the bias is removed, the differences in earnings between the siblings and twins is then credited to education. Other studies use panel data or repeated observations over time [

42,

43] to eliminate unobserved abilities because the effects on the return on education of these latent variables are constant over time.

A final and quite popular method for dealing with ability bias is the use of instrumental variables (IV) for schooling. Following the requirement of IVs, a valid instrument should be correlated with the exogenous variable (education), but not with ability and, thus, not with earnings. Various studies have adopted IVs from the supply (institutional features) and demand sides. Examples of institutional features include proximity to the nearest high school/university [

44,

45,

46], the minimum school leaving age [

47,

48], and school quality [

49]. From the demand side, studies have used quarter of birth [

50,

51], family background, such as parents’/father’s education [

52,

53], and income as IVs. The IV method has limitations, especially the issue of weak instruments, which leads to an asymptotic bias toward the corresponding ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates [

19]. Spence [

54] points out that individuals’ latent abilities might already be reflected in their acquisition of an educational degree, because people with higher abilities know that earning a degree is an effective way to communicate or send a signal to potential employers. In other words, education can be interpreted as a means through which to enhance productivity or as an indication of existing inherent productivity. Spence also argues that firms tend to believe that credentials are positively correlated with better-quality candidates and rely on these credentials when making recruitment decisions [

54].

Nonetheless, in their comprehensive reviews of the literature, Becker [

55], Griliches [

33], and Becker and Tomes [

56] come to a similar conclusion that ability bias is overestimated. Furthermore, they find that these biases are small, with ability only explaining 1% of the returns on education [

33]. According to Griliches [

33], when schooling is treated symmetrically with ability measures, it may be subject to measurement error, and may also be correlated with the error term in the earnings function. Therefore, biases caused by unobserved-ability variables and measurement errors tend to cancel each other out. In the words of Heckman, Lochner, and Todd [

57], the study of endogeneity in relation to returns on schooling “is far from settled”.

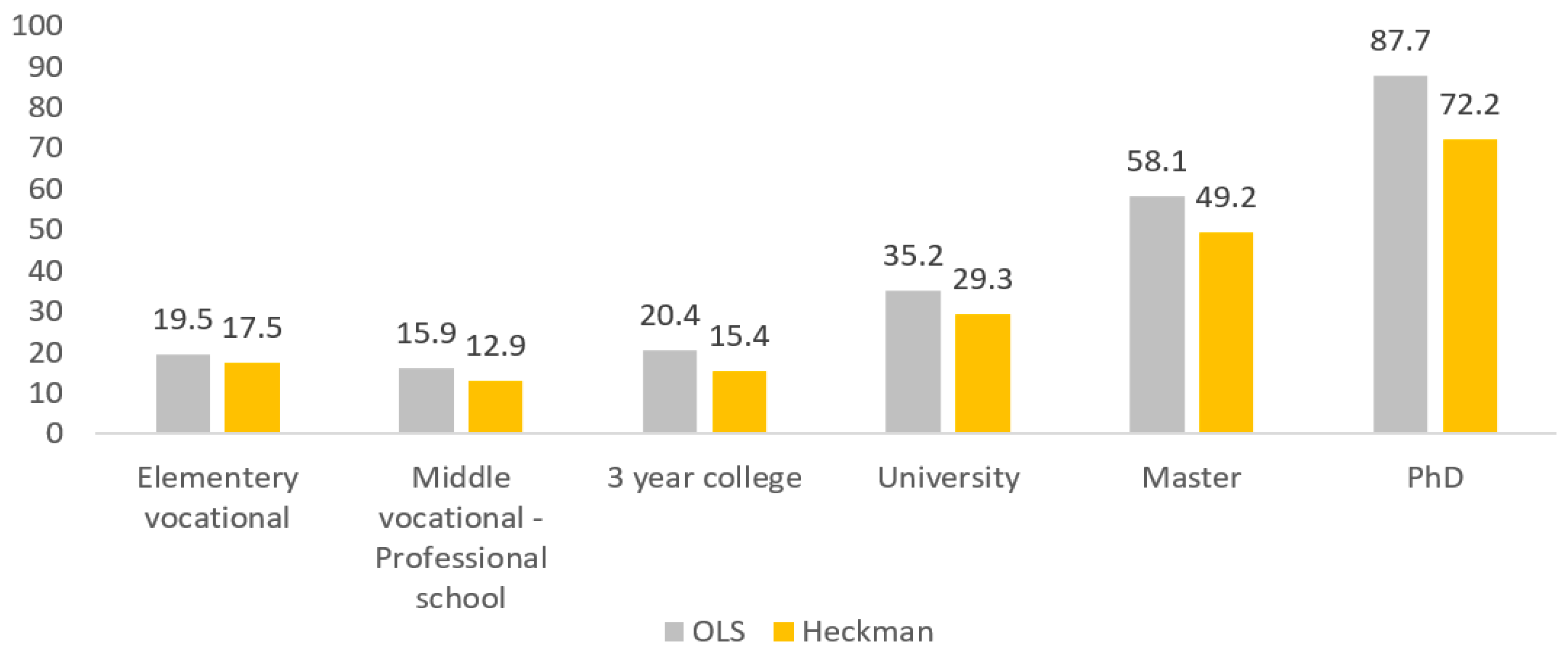

2.2.2. Selection Bias

The problem of selection bias in the Mincer model was first raised and discussed by James Heckman [

58]. The argument here is quite simple. With this earnings equation, we can only capture representative information of the wage-earner population (a subset of the actual population under study), thus excluding those who are unpaid or unemployed. This causes a nonrandomly selected sample and, consequently, a downward bias in the OLS estimates when using the Mincer equation. Here, we employ the two-stage Heckman correction method to address the issue of selection bias. Statistical software packages such as Stata offer simple ways in which to execute this two-step estimator. The following is a brief explanation of the method.

First, we have the basic wage Equation:

where W is an individual’s earnings, and X

i is a vector of her schooling, experience, gender, and so on, related to her productivity. We can only observe W when the person enters the waged labor market. When individuals do not enter the labor market, it is likely that their offered wage is below their reservation wage.

We then have a second equation relating to employment, that is, the lowest rate at which an individual would be willing to accept a particular job offer:

where Z

i is a vector of explanatory variables (schooling, experience, gender, parents’ income, and/or education, which explain her constraint), and E

*i = W

i − E’

i is the difference between the wage and the reservation wage E’

i. Equation (1) can be a probit-type selection model describing whether a person will decide to work. If the wage is below the reservation wage, she chooses not to work. We observe only an indicator variable for employment, defined as E = 1 if E

*i > 0, and E = 0 otherwise.

Furthermore, we assume that the error terms u

1i and u

2i are normally distributed with mean zero and are positively correlated. Here, (u

1i, u

2i) are independent of both sets of explanatory variables X and Y:

where ρ

12 is the correlation coefficient.

Heckman’s two-step model first estimates a so-called inverse Mills ratio (or Heckman’s lambda) using the following probit model:

where ϕ denotes the standard normal density distribution, and Φ is a normal cumulative distribution function. In the second step, λ

i is used in the original wage Equation (1a), as follows:

As long as u

2i is normally distributed and η

i is uncorrelated with (or independent of) λ

i, the Heckman model is consistent [

59].

One of most challenging tasks when employing the Heckman two-step model is to find a good identification strategy. All explanatory variables used to predict the likelihood of employment are based on human capital theory. Weakly identified variables can worsen the results or show misleading results when attempting to correct the sample selection bias, producing large distortions.

Finally, other factors in addition to latent abilities might affect a person’s earnings, such as gender, marital status, job industry, and job sector, among others [

60,

61]. Therefore, the original Mincer equation is extended here as follows:

where Ln w is an individual’s log monthly/hourly wage, Z is an education-level dummy, X denotes age/potential experience, and ε represents other control variables.

The regression is also run using the Heckman correction model, using appropriate IVs to check for selection bias (see the Methodology section).

2.3. Studies on the Return on Education in Vietnam

The return on schooling has been a topic of interest for researchers in Vietnam, with most results showing a positive relationship between education and earnings, although with different magnitudes.

Most prior studies that describe the benefits of a return on an investment in education have been based on the USA. For example, McMahon [

62] offers new estimates of the social rates of return for a high school education and for a four-year college education for males and females in the United States, using microeconomic data from US Census Bureau surveys for the period 1967 to 1988. These are compared with real rates of return on investments in plant and equipment and in housing since 1947. The results reveal a significant decline in the returns on a junior high school education for those who leave (from 21 to 7%), steady rates of return on a high school education, averaging 12%, and real rates of return at the college level, rising gently to 12–14% levels in the late 1980s, with a dip in the mid-1970s. The rates of return on housing, including capital gains, were only 5% during the same period, compared with 15% for investments in plant and equipment. In addition, Psacharopoulos [

63] provides a broad overview of human capital theory and presents highlights of the most recent evidence on private and social returns on education. A distinction is made between narrow social returns, as traditionally estimated in the economics of education literature, and wide social returns, which include externalities. The distributive implications of several education finance policies are discussed. We conclude that the policies most conducive to social welfare are those that prioritize investment at the lower levels of education, including preschool, and the acquisition of general, rather than occupation-specific, skills.

A few studies focus on the period after the Doi Moi (English: Renovation) economic reforms initiated in 1986, which aimed to abolish the command economy and create a “socialist-oriented market economy”. In particular, Moock, Patrinos, and Venkataraman [

64], using earnings data from 1992 to 1993, estimate that the rates of return were relatively low compared with those of other developing countries during that time. The returns on primary and university education averaged 13% and 11%, respectively, but were only 4% to 5% at the secondary and vocational levels. Gallup [

65] reports similar results, stating that the payoff for one additional year in school, which doubled from 1993 to 1998, was still low at 5%.

However, Liu [

66] observes a considerable shift in demand toward more educated workers between 1992 and 1998, when the earnings of people with a tertiary education increased significantly in comparison with workers with a below-primary education. In a more recent work, using updated data from for the period 1998–2014, Doan, Tran, and Le [

67] estimate a greater increase during this same period than do Glewwe and Patrinos [

68], Gallup, [

65] and Moock, Patrinos, and Venkataraman [

64]. The authors also conclude that returns continued to increase until 2008, after which they appeared to decrease between 2008 and 2014, which they credited to the rapid expansion of education and the slow-down of economic growth and transformation.

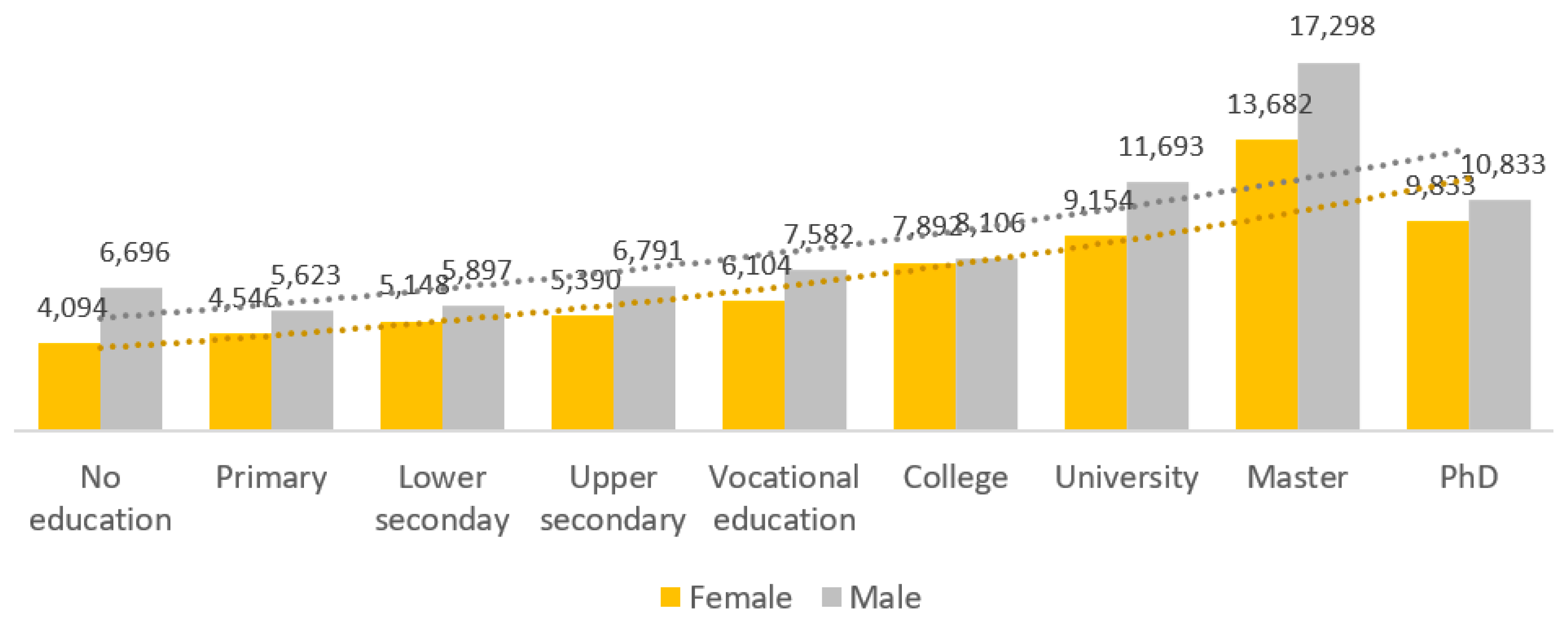

Furthermore, one of the most common findings in these works is higher returns on education for female than for male workers in the labor market (similar results have been found in other countries). Studies on wage inequality [

65,

69,

70] all find a sharp reduction in gender pay gap disparities for the wage-employed population associated with the Doi Moi reform. However, using the decomposition method, these studies find that the convergence of the Vietnamese gender gap in the 1990s hid an adverse change in discrimination. As in China, women still faced substantial wage discrimination owing to employers’ preferences and the competitiveness of female employees [

69].

As a transitional economy, Vietnam has a somewhat distorted labor market. Using data from 1993 to 2008, Phan and Coxhead [

71] explore a more interesting dimension of inequality: Households with and without access to jobs in the state sector. Economic policies biased toward SOEs have yielded certain privileges for public servants. State-sector jobs provide stable incomes, promotions, and overall longevity and are also, in general, less demanding in terms of time and productivity. This leads to fierce competition for bureaucrat positions despite the relatively low salaries. In addition, because the number of available positions is limited, organizations tend to favor people with connections based on family ties. As a result, according to Phan and Coxhead [

71], households with these types of “relationships” (or quan he) tend to invest more in education for their children. In contrast, families who have little incentive to study or obtain credentials encourage their offspring to opt out of school early and sometimes use that investment money as a bribe for a job [

67]. This phenomenon has caused severe corruption in the Vietnamese labor market, popularized in the term “Con ong chau cha” (similar to the idiom “born with a silver spoon in the mouth”), which refers to people who are hired and promoted based on their parents’/grandparents’ connections. However, since the economic reform, Vietnam has tried to privatize SOEs, promote private firms in specific industries, and attract foreign investment. Therefore, the situation may have changed since then.

Lastly, other studies have adopted different methods, such as ethnic inequality [

72] or returns on private versus public schooling systems [

68]. However, thus far, no studies have focused on regional differences or analyzed the two biggest cities separately, although Gallup [

65] does estimate that workers in Hanoi and HCMC received a substantial (50% higher) wage premium over the rest of the country in the period between 1993 and 1998.

Studies on the return on education in Vietnam often face difficulties related to data availability and sufficiency. Most research on this topic uses data from the Vietnam Household Living Standard Survey conducted by the Vietnam General Statistics Office, which, until 2002, was criticized for employing relatively small samples. Moock, Patrinos, and Venkataraman [

64] recognize the limitation in their analysis that they could only include wage-earners, even though 80% of the Vietnamese labor force was self-employed at the time. Moreover, most studies, except for a few recent works [

67,

73], do not consider proxies for individual ability or the motivation provided by family resources, even though investment in education in Vietnam faces a high liquidity constraint [

68,

74]. Some acknowledge, but do not include selection bias in their analyses [

64,

70].

This study, despite overcoming several of the limitations of previous studies, deals with similar shortcomings related to the data. In the next section, we discuss our data set and methodology.

5. Conclusions

The main conclusions from this empirical analysis are that the labor markets in Hanoi and HCMC are quite different to those described in previous studies that use country-level data; in addition, differences exist between these two cities as well.

As the two biggest economic hubs in Northern and Southern Vietnam, Hanoi and HCMC have a more sophisticated and competitive labor force than that of the rest of the country. General education no longer pays a premium; instead, workers need to have at least a vocational degree to significantly increase their wages. This is contradicted by the current problems experienced by vocational schools that are struggling to draw sufficient students (owing to problems related to quality, and the common perception that such schools are only for children who cannot pursue a “proper” education), some of which have been forced to close down. Thus, additional career orientation activities need to be implemented at the secondary education level. This will encourage students to at least earn a vocational education before entering the labor market, because the demand for such skills is significant in these two cities.

With regard to the differences between the cities themselves, our statistical results show that, in general, HCMC offers higher salaries. Furthermore, the capital pays more for education, whereas the younger city is more rewarding toward experiences (although the gap is not large). We obtain these results after controlling for multiple variables, including employment ownership type, which is one of the factors that can explain these differences. Recall that Hanoi has traditionally emphasized education and status, which in this case, might have overestimated the market value of education. If this is true, there is no doubt that it has contributed to the existing social phenomena (and corruption issues) of people “buying” credentials and exchanging bribes for awards, titles to get jobs, and higher salaries. Furthermore, it hinders Hanoi from hiring the “best” people, especially in areas when hands-on experience is more important than a degree, such as the creative sectors. As the number of (large) state-owned and equitisatized (Vietnamese English term: An SOE that has been converted to a public limited company or to a corporation) firms has increased, the reality is that degrees are being used more than ever as tools for promotion. This is happening everywhere in the country, including HCMC, although our statistical results indicate that Hanoi has the bigger problem of the two.

Hanoi may be able to look to HCMC to find solutions to their problems. HCMC has become an economic leader of the country by successfully building and developing an environment that fosters entrepreneurs and business-minded people. These start-ups and private firms make the city a diverse, flexible, open place for skilled (but not necessarily the best educated) workers to prosper. As of 2016, HCMC accounts for one-third (200,000 of 600,000) of the operating firms in the country. There is also a noticeable trend of well-educated, capable, and enterprising workers moving from Hanoi to HCMC, because the later can offer better job opportunities and a better business and working environment. With a population of 90 million people, Vietnam in general, and Hanoi in particular, has much room to expand. The capital possesses the infrastructure, educated workforce, and political advantages, but needs a more open, tolerant, and pro-business mindset.

Hanoi can use of its large pool of highly educated workers to develop more knowledge-intensive activities. HCMC can achieve further growth (perhaps at the robust growth rate of leading cities in China) by improving the quality of general and nonformal education to meet labor’s diverse learning needs. The younger city has received increasing pressure to invest more in infrastructure and education. On the other hand, these two cities are compatible and should explore synergistic opportunities. How well Hanoi and HCMC learn to cooperate will contribute significantly to the development of the cities and the country.

In conclusion, this study revisited the linkage between educational attainment and labor market outcomes in Vietnam, although on a specific geographical scale, and takes a relatively different direction. This study provides a starting point to showcase the need to study returns on education in a smaller setting, whether at the city/province or regional levels. Since Vietnam is a developing economy with a high level of economic, developmental, and educational heterogeneity, studies targeting certain geographical locations can offer specific implications and solutions for policymakers.

Unfortunately, we were not able to address the ability-bias issue, as discussed earlier. Furthermore, in terms of ability measurement, we could not incorporate cognitive skills (critical thinking, problem-solving) or behavioral skills (teamwork, communication) into the analysis. These skills are lacking in the labor force but have been becoming increasingly important to employers in Vietnam. For example, the World Bank conducted research in 2014 titled, “Skilling up Vietnam” to address this issue. However, such complex variables are not included in the VHLSS data set.

In addition, the Heckman correction model can use more appropriate instruments, such as the number of children (especially under age six). Furthermore, we would like to test the chosen IVs for invalid/weak instruments and discuss the issue of education quality in Vietnam.