Opportunities for Slow Tourism in Madeira

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The State of the Question of Slow Tourism

2.1. The Origin of Slow Tourism

2.2. Attributes and Definition of Slow Tourism

2.2.1. A Change in the Concept of Travel and the Use of Time during the Trip

2.2.2. An alternative to Mass Tourism, Local, Cultural

2.2.3. Improve the Sustainable and Natural Environment

2.2.4. Promoting Changes in the Quality of the Experience as It Offers Authenticity

2.2.5. Feasibility and New Business Development

- In any case, numbers of flow—movement members, the variety and the rapid international growth of slow tourism, predict important opportunities for tourism suppliers seeking a position in this market.

- While slow tourism has inspired new ways of doing business, it is difficult to quantify its economic impact, since it is an emerging market. In the capacity to create new businesses, and therefore wealth and jobs for slow tourism destinations, we will distinguish six sections:

- ○

- Thanks to slow tourism, new businesses are generated, such as artisan and zero-kilometer markets; museum spaces; informative, meeting, and exchanging places; the transformation of local products; the expansion of visits to places less known by the general public; and the recovery of the local social culture.

- ○

- New services of accommodation, restaurants and catering services, guidance, interpretation, and transportation and marketing.

- ○

- The development of environmental policies around the landscape, heritage, green transport, recycling, and the circular economy

- ○

- The seasonally adjusted tourist seasons, insofar as this type of tourism is not so conditioned by the weather or the standard seasons.

- ○

- Entrepreneurship that embraces creativity.

- ○

- General technological development; Caffyn [37] says that slow tourism is absolutely compatible with new technologies; he even insists they are needed.

- A more personalized, quieter trip invites one to spend more, due to the value of experience. Consumers’ actively choosing smaller providers assumes their ability to afford the often-higher prices that local retailers may charge for goods/services, due to their lack of economy of scale. If we are what we eat, then the same could be said of our travel choices [5]. In addition, as materialistic values are reduced and emotions and affects increase, availability of spending increases [57,59]. This would imply that a better service, removed from overcrowding, would facilitate a better profitability of the establishments.

- The result of the previous points would mean that business profit could support the new model.

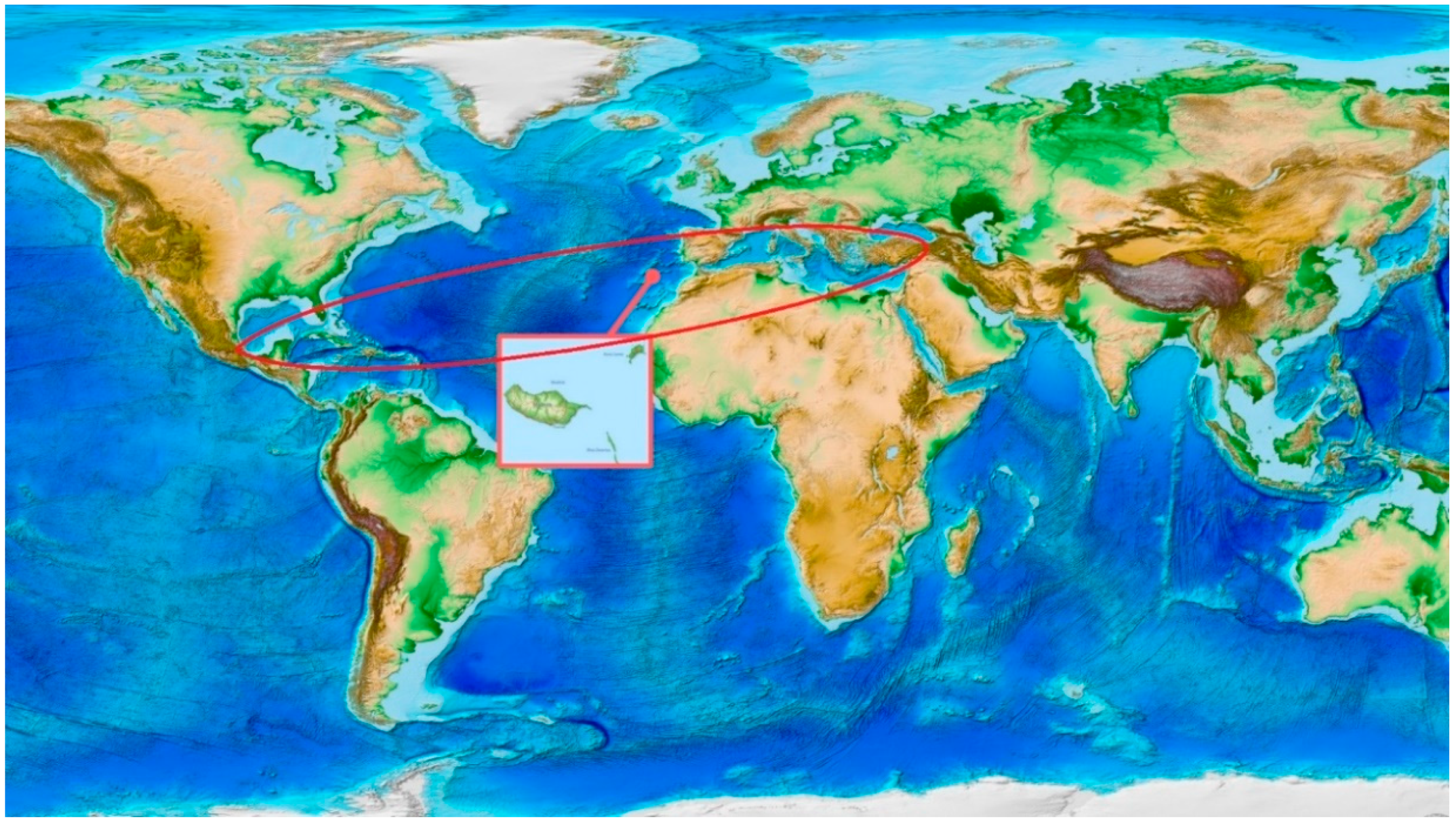

2.3. Slow Tourism in Madeira

3. Objectives, Hypotheses, and Methodologies

- To demonstrate H1: (a) Analysis of strategic plans and compliance with results: Evolution of the compared overnight stays; (b) Madeira benchmarking with the Canary Islands, Mallorca, Sicily, Corsica, Malta, Cyprus, Cabo Verde, and Azores: Global number of tourists, global number of rooms, ratio of tourists per square kilometer, ratio of occupancy versus seasonality, and number of tourists versus residents.

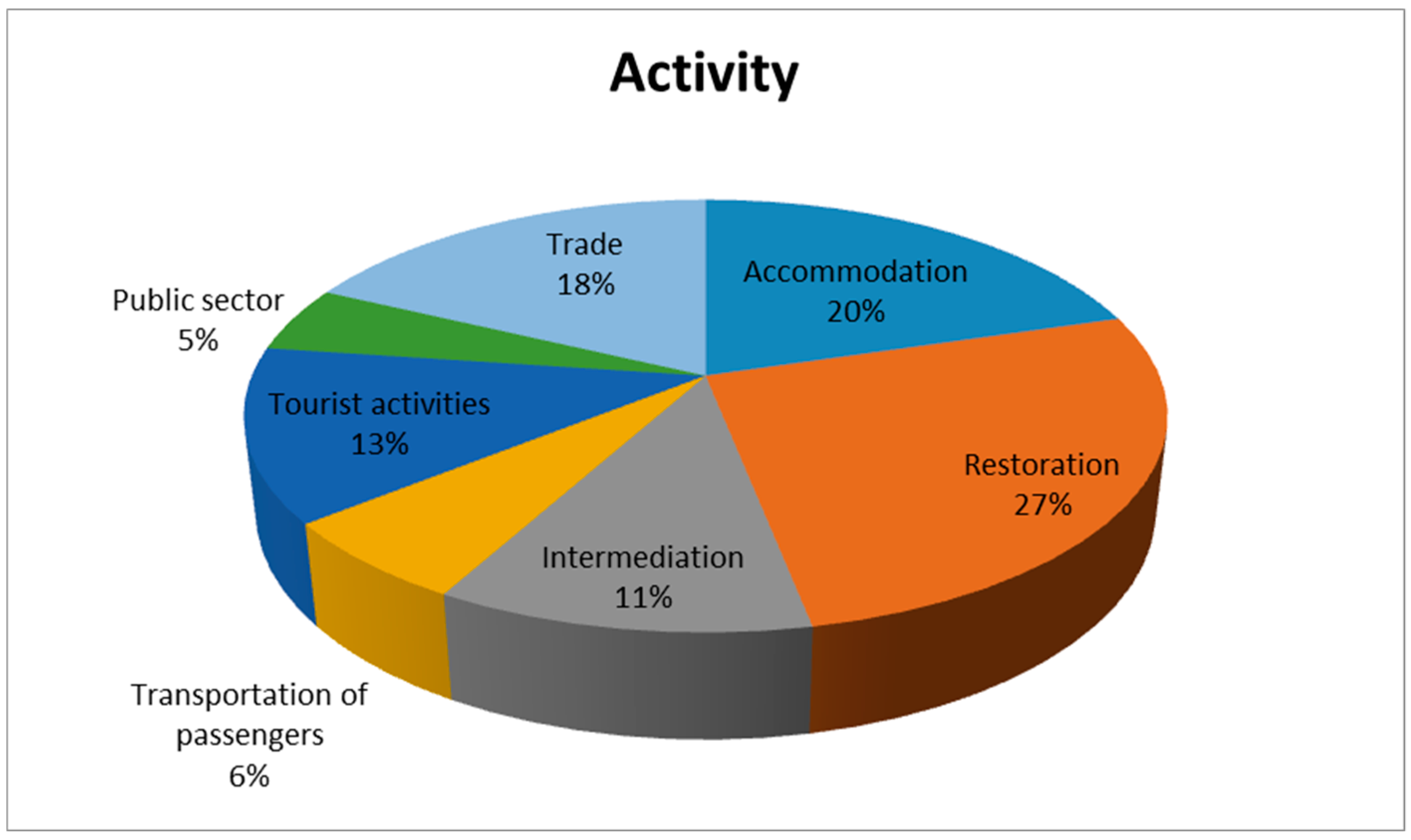

- To demonstrate H2 and H3, a questionnaire was written to obtain the perception about the topic, being sent to a representative sample of hotels, restaurants, shopping centers, transportation companies, travel agencies and online travel booking sites, and tourist attractions.

- Accommodation: 124 establishments, of which 33 were surveyed (26.61%). The Accommodation heading includes hotels of all categories, quintas, residential accommodations, and hostels.

- Food and Beverage: 167 establishments, of which 43 were surveyed (25.75%). Within Food and Beverage, restaurants and bars were included.

- Shopping: 106 establishments, of which 29 were surveyed (27.36%). Within Shopping, we included stores selling all kinds of products from souvenirs to clothing and consumer goods.

- Transportation: 74 establishments, of which 10 were surveyed (13.51%). Within Transportation, we included bus companies, rental car companies, bicycles, public transport, ferry, and cruise.

- Intermediation: 346 establishments, of which 18 were surveyed (5.20%). Within Intermediation, travel agencies are included.

- Tourism Activities: 78 establishments, of which 21 were surveyed (26.92%). Within Tourism Activities, we include outdoor activities, tours, walks to levadas, and caravel tours.

- Public Sector: 29 establishments, of which eight were surveyed (27.59%). Within Public Sector, autonomous government, municipalities and public corporations are included.

4. Results

4.1. Data Collection

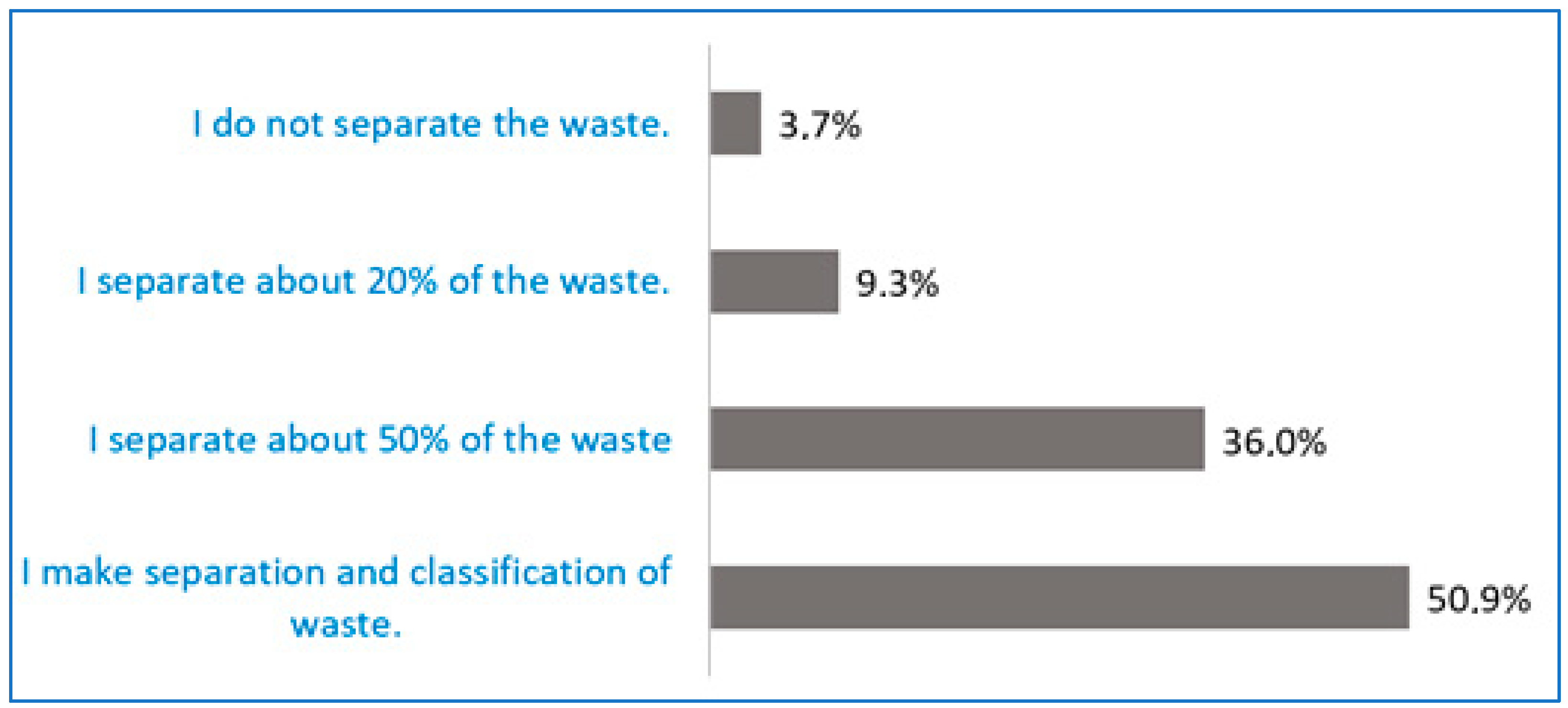

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

4.2.1. H 1: The Characteristics of Madeira’s Tourism Development Fit in with the Basics of Slow Tourism

Analysis of the Strategic Plans for Madeira’s Tourism

- Objective: To invest in creative and cultural industries, natural and cultural heritage, and recreational and leisure activities, in order to directly and indirectly qualify the tourism area, encouraging the creation of qualified employment in the sector;

- Area of activity: Religious and cultural touristic circuits, nature tourism, nautical tourism, health and wellness tourism, and gastronomy and wines;

- Line of action: Implementation of initiatives promoting the urban, environmental, landscape, and social quality of the destination;

- Priority activities: Introducing sustainability requirements to ensure the preservation of tourist attraction areas in tourism projects, including:

- ○

- Developing specific tourism awareness programs for the natural, historical and cultural value of the region.

- ○

- Developing programs aimed at introducing management mechanisms; namely, rationalization of consumption and environmental efficiency; energy efficiency; renewable energies; waste management; and good practices in the value chain.

- ○

- Reassessing and confirming the repositioning of well-being and to create circuits, networks and tourist itineraries according to the repositioning of the offer to the tourist (orientation to the experience).

Evolution of Overnight Stays

Madeira Benchmarking

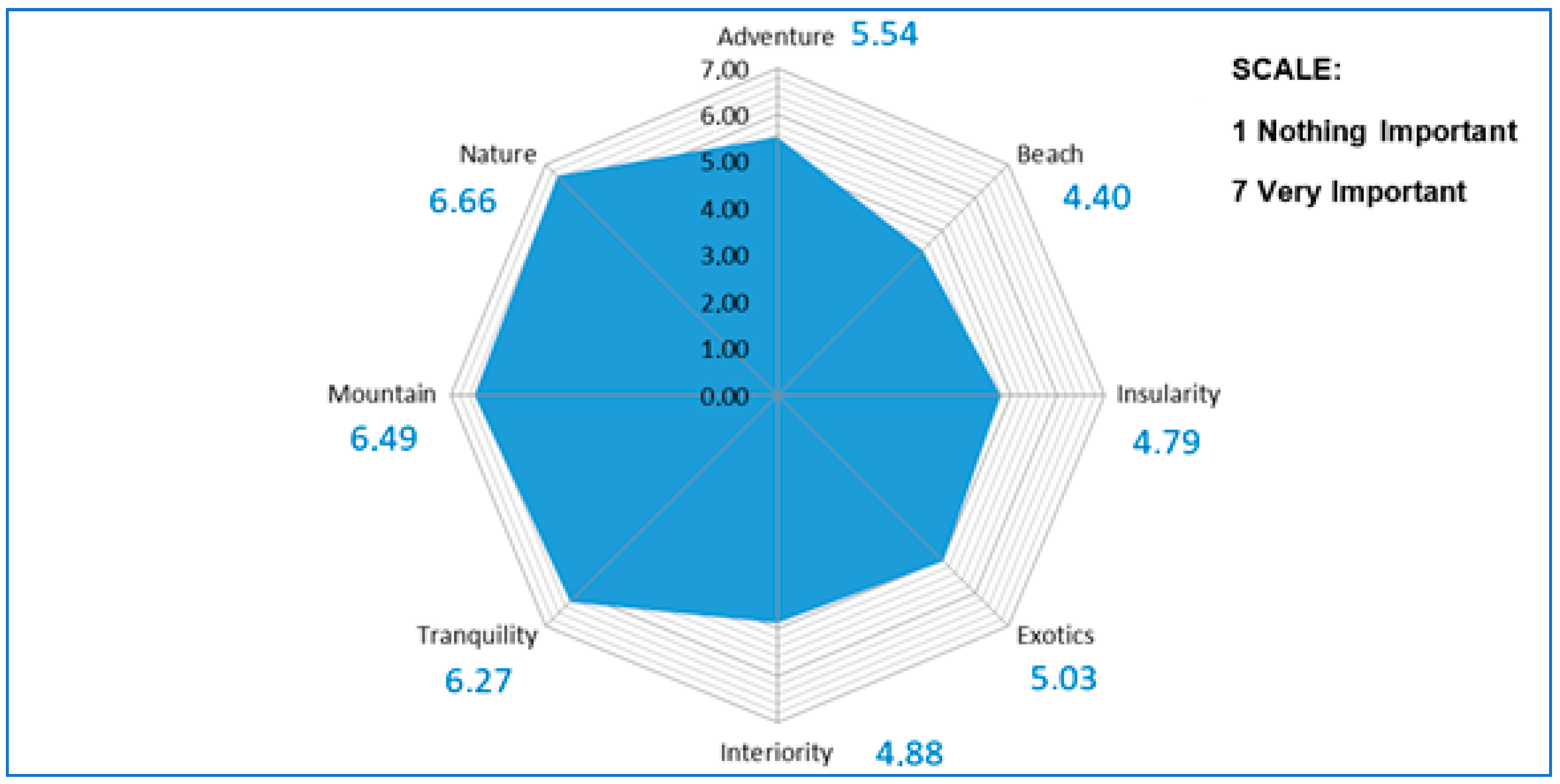

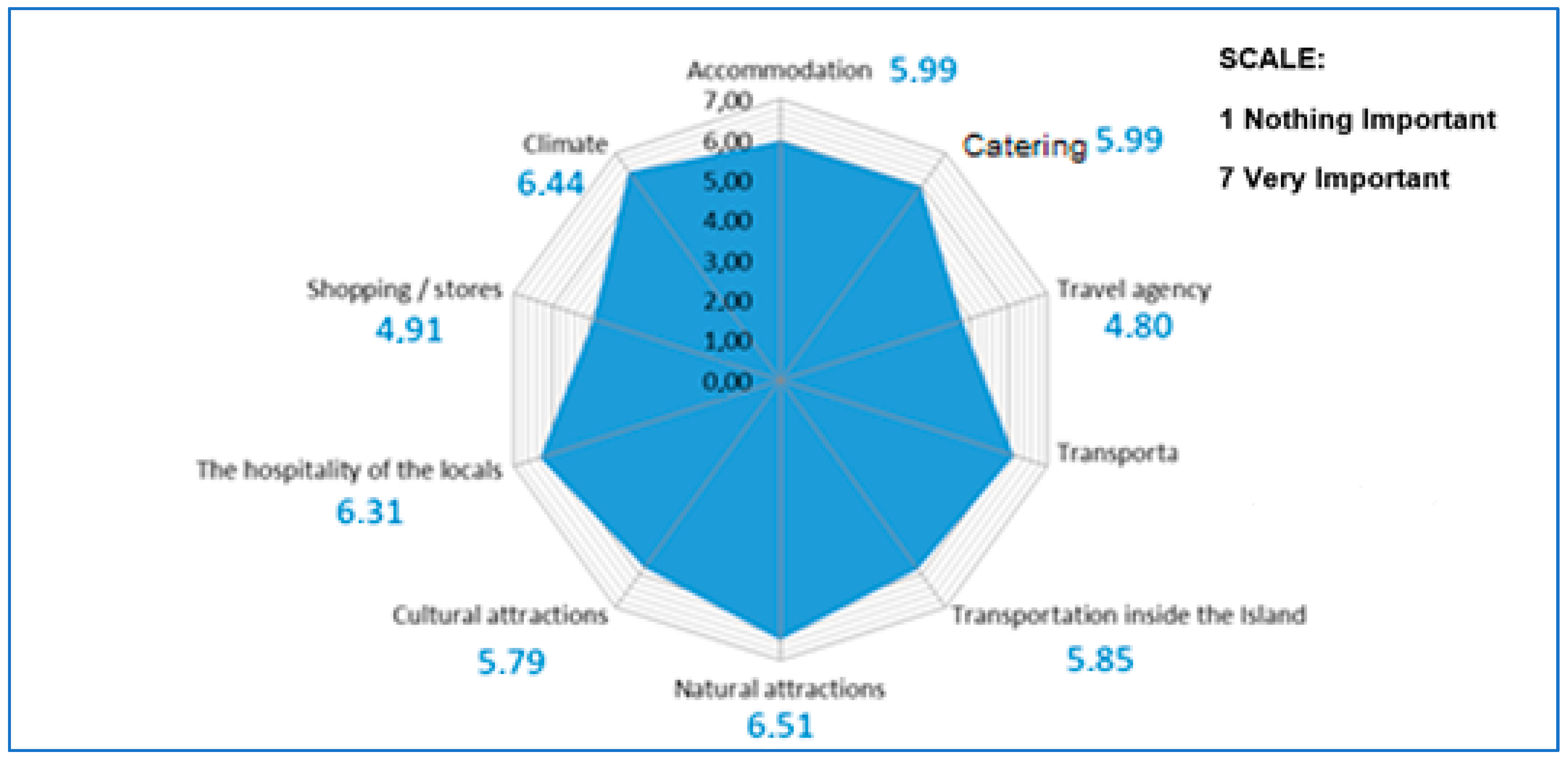

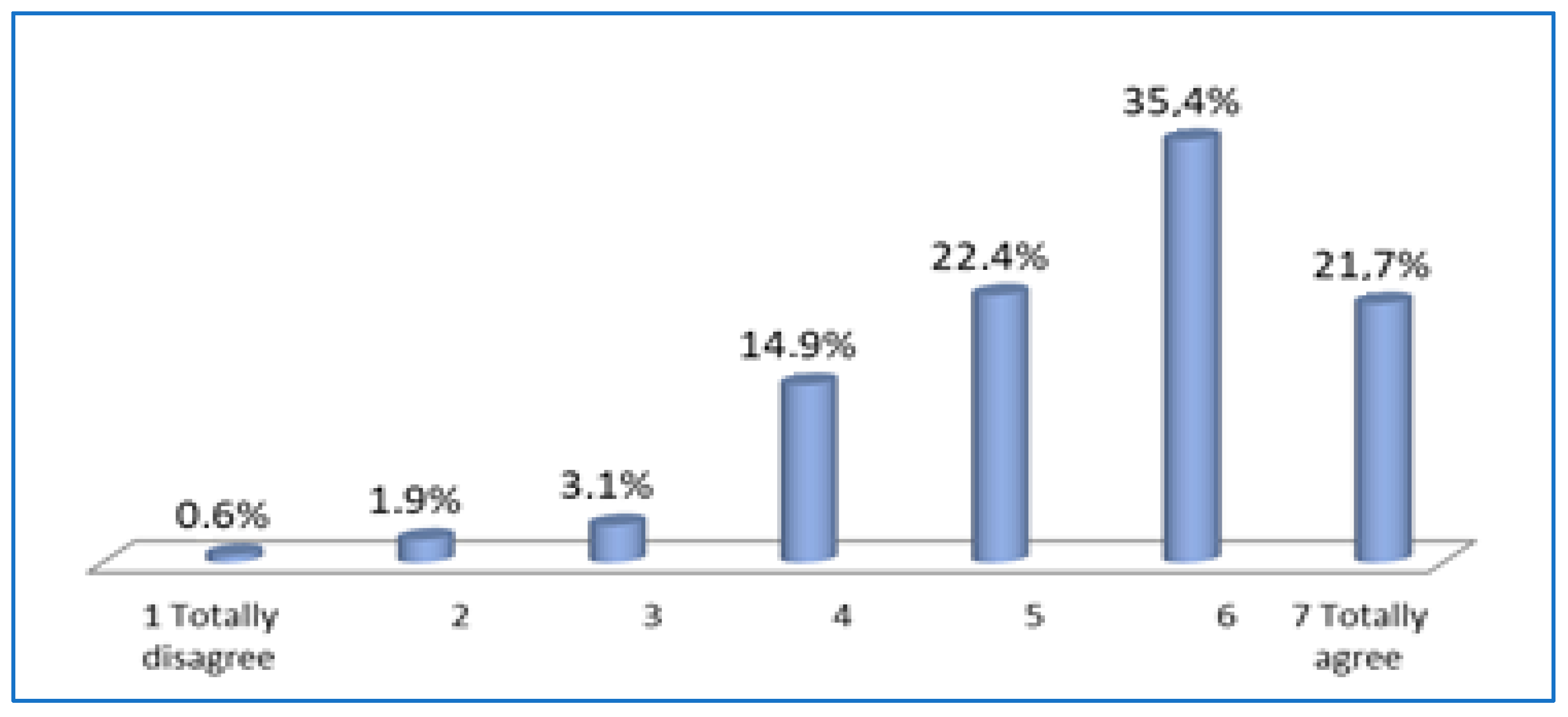

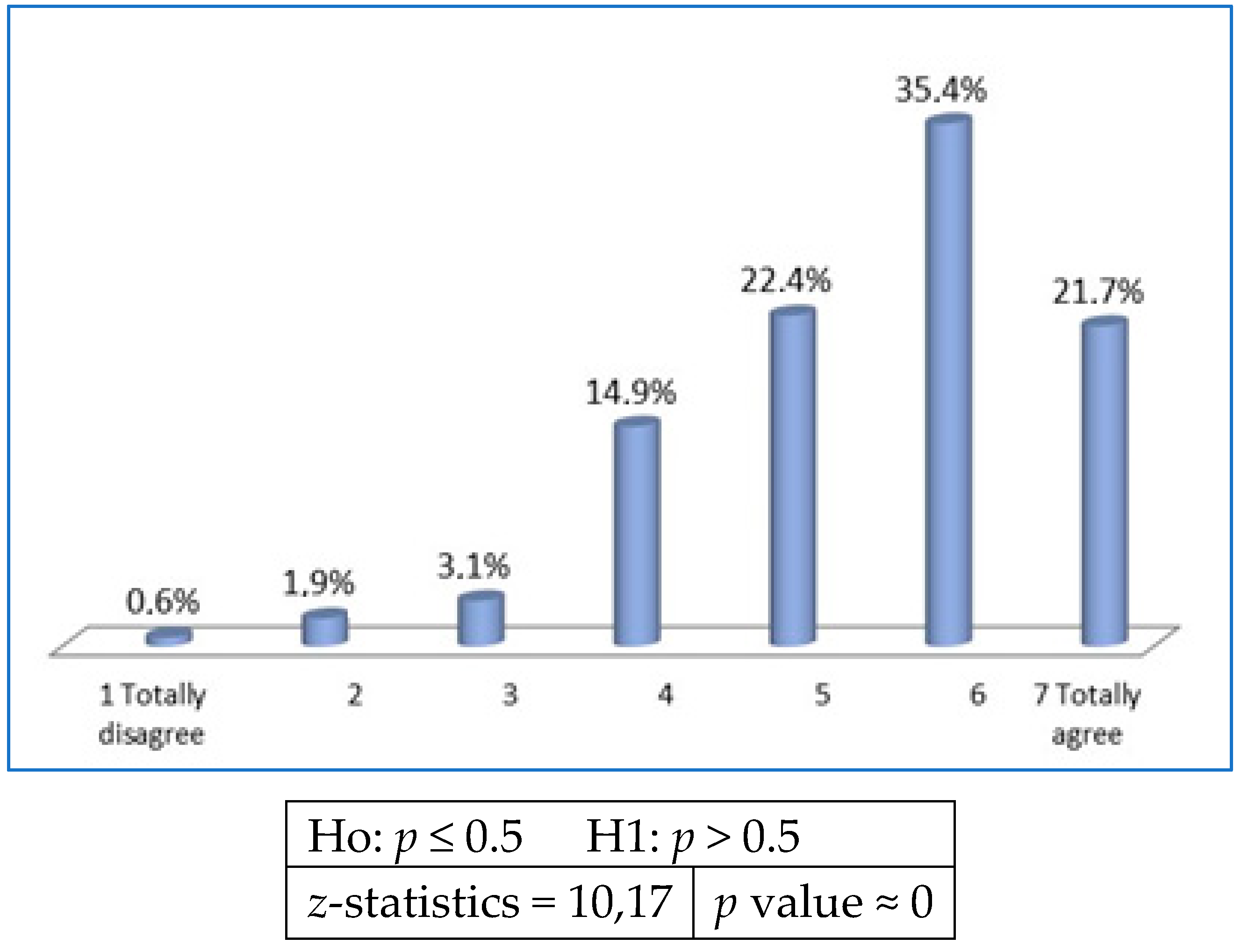

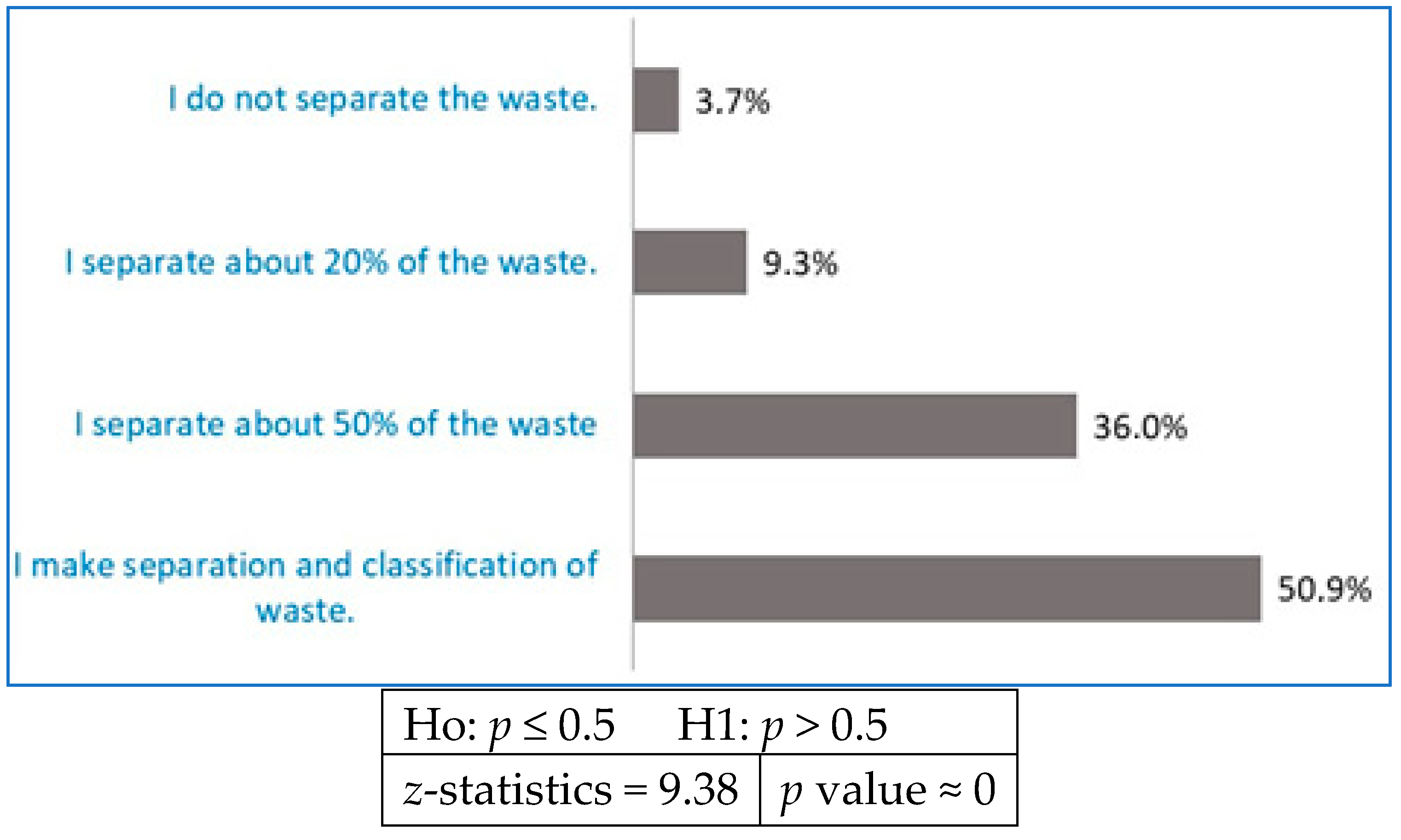

4.2.2. H2: There Is No Openly Favorable Attitude toward Slow Tourism among Tourism Entrepreneurs in Madeira

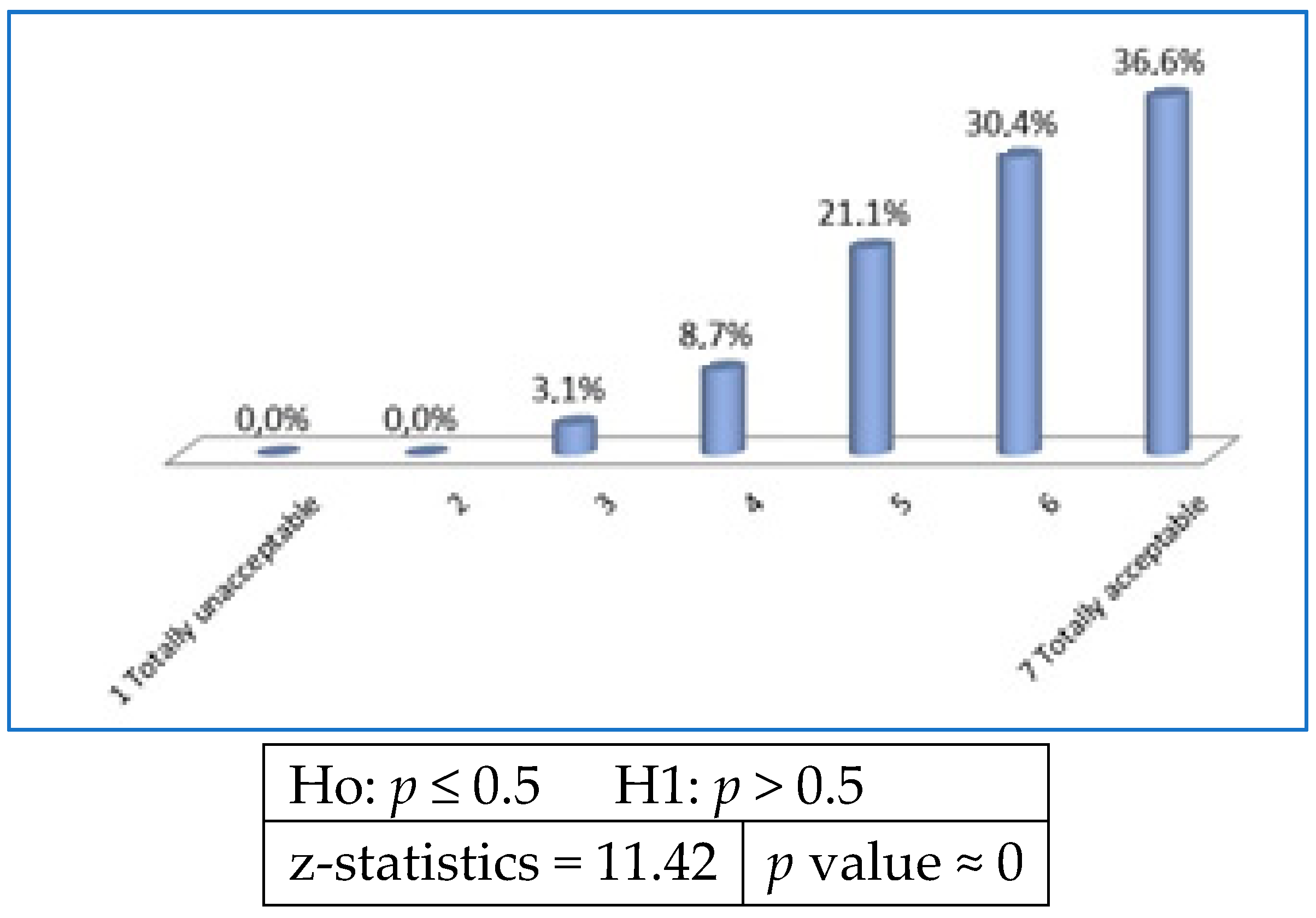

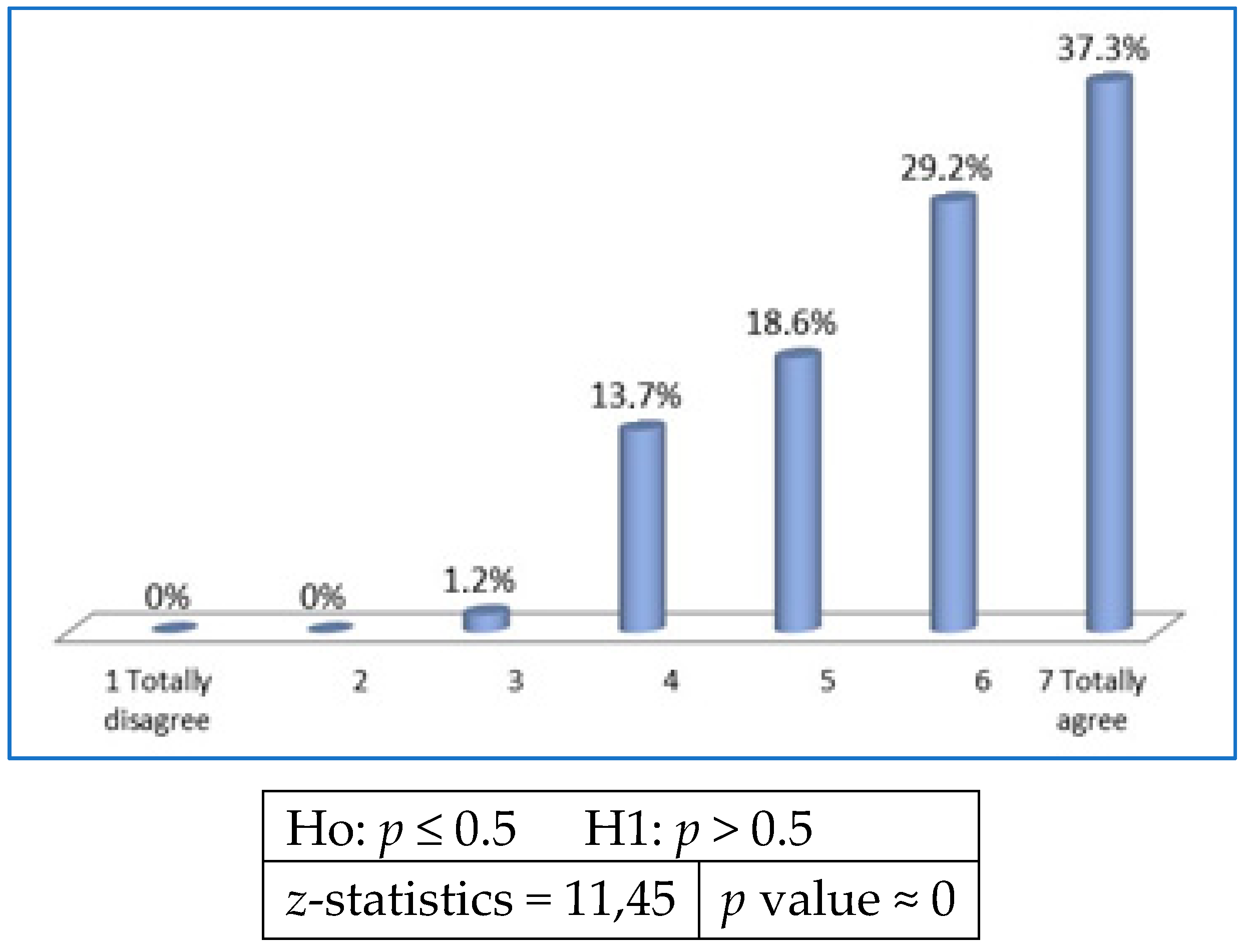

4.2.3. H3: Tourism Providers on the Island Would Be Willing to Carry out This Model of Tourism and Apply It

5. Discussion

- The slow tourism movement was born as a change in the concept of travel, as an alternative and reaction to mass tourism, offering instead the authentic, the local and the cultural, as a driver of zero-kilometer products, the sustainable, and the quality of the experience. In the case of Madeira, it has originated not as the result of a reactive movement but rather as a natural sequence of the interest of the main actors, supported by Madeira’s insularity and ultra-periphery. This study reflects the vision of entrepreneurs as the first guarantors of the model.

- It is true that the ideas of slow tourism originated outside of Madeira, but when compared with the vision of entrepreneurs, it turns out that there is a significant alignment. In similar cases of destinations where tourism development has been low or incipient, whether island territory or not, it can be deduced that the approach to the values of slow tourism accelerates the construction of a slower and more sustainable model. It is not a revision of the model, but an impulse to offer the same from the beginning.

- Entrepreneurs are convinced that tourists are willing to pay more for a better experience. In favor of Madeira’s tourism offer is the fact that the island has not been forced to rehabilitate either its territory or its heritage since it did not undergo a mass tourist invasion. Therefore, in this type of destination there is no cost for the change of image; instead, the slow tourism model develops or advances positively.

6. Conclusions and Limitations

6.1. Conclusions

- -

- Slow tourism is a movement that brings together a set of distinct characteristics with respect to the life cycle of mass tourism that began in the 1960s. These characteristics are related to a different concept of travel and visits: Less rapidity and more tranquility; seeking to discover the small, the peculiar, and the personal; an alternative way of approaching routes, local culture, and zero-kilometer products; keen awareness and care of the environment; and emphasis on the search for authentic experiences.

- -

- In line with slow tourism, new types of tourism are developed and incorporated as new motivations for a trip: Adventure, agritourism, cruises, ecotourism, education, indigenous, medical, musical, religious, volunteering, sport tourism, trekking, running, birdwatching, and so forth.

- -

- Slow tourism’s development in a given destination offers opportunities to improve its position as a tourist attraction and increase its economic income, especially when assuming that the tourist is willing to pay more for a superior experience.

- -

- The path of slow tourism demands a planning model radically different from the life cycle stage of mass tourism.

- -

- A destination does not need to reach an advanced stage of the life cycle and be forced to react by proposing alternative models of tourism management. A slower, more sustainable tourism can be chosen, based on an endogenous impulse, for advantages such as its low exploitation of general resources. Such is the case for Madeira: The island has adopted the same convictions without the trauma of having been forced to abruptly apply the tourism brakes and remediate damage from mass tourism. The opinions of Madeiran tourism entrepreneurs confirm this sustainable endogenous vision, even without their having explicitly learned the values of slow tourism.

- -

- Thanks to the happy confluence of the endogenous impulse of tourism planning with the ideas of slow tourism, the destinations, insular or not, will assimilate the sustainable models more quickly. This opens the way for more rapid tourism development, within the criteria of sustainability, for emerging destinations. In this sense, Madeira can be offered as a remarkable case.

- -

- In the majority opinion of our sample, tourists are willing to pay more for a better experience. It is interesting to find this conviction among the entrepreneurs of a destination. However, for this assertion to be verified, it would have to be compared with the opinions of consumers who choose to accept offers with different intensity, quality of experience, and price.

6.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguiló, E.; Alegre, J. La madurez de los destinos turísticos de sol y playa. El caso de las Islas Baleares. Papeles Econ. Española 2004, 102, 250–270. [Google Scholar]

- Marson, D. From mass tourism to niche tourism. In Research Themes for Tourism; Robinson, P., Heinttmann, S., Dieke, P., Eds.; CAB IInternational: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, J.; Lumsdon, l. Slow Travel and Tourism; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; 232p, ISBN 978-1-84971-113-5. [Google Scholar]

- Heitman, S.; Robinson, P.; Povey, G. Slow food, cities and Slow Tourism. In Research Themes for Tourism; Robinson, P., Heitman, S., Dieke, P., Eds.; CABI International: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 114–128. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, L.L.; Back, R.M. Slow food, Slow Tourism & sustainable practices: A conceptual model. In Sustainability, Social Responsibility and Innovation in Hospitality-Tourism; Parsa, H.G., Narapareddy, V., Segarra-Ona, J., Chen, R.J.C., Eds.; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiló, E.; Alegre, J.; Sard, M. The persistence of the sun and sand tourism model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithalm, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A Multiple-item Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Georgic, G.; Bulin, D.; Dorobantu, M.R.; Stefania, B.; Nistoreanu, P. Slow Movement as an Extension of Sustainable Development for Tourism Resources: A Romanian Approach. In Proceedings of the Conference: 20th IBIMA Conference, Special Edition, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 25–26 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, L.L.; Lee, M. CittaSlow, slow cities, slow food: Searching for a model for the development of Slow Tourism. In Proceedings of the Travel & Tourism Research Association, 42nd Annual Conference: Seeing the Forest and the Trees–Big Picture Research in a Detail- Driven World, London, ON, Canada, 19–21 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Clancy, M. Conclusion: The promises and pitfalls of slow. In Slow Tourism, Food and Cities; Clancy, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; 248p. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.W.; Ponsford, I.F. Confronting tourism’s environmental paradox: Transitioning. for sustainable tourism. Futures 2009, 41, 396–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, P.F.; Seabra, C.; Paiva, O. Slow cities (Cittaslow): Os espaços urbanos do movimento slow. Rev. Tur. Desenvolv. 2014, 21/22, 191–193. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, D.; Timms, B. Are Slow Travel and Slow Tourism Misfits, Compadres or Different Genres? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2012, 37, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Fullagar, S.; Markwell, K.; Wilson, E. Slow Tourism: Experiences and Mobilities; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2012; 248p, ISBN 978-1845412807. [Google Scholar]

- Babou, I.; Callot, P. CO2 et tourisme: Vers de nouvelles segmentations? In Proceedings of the 12èmes Journées de Recherche en Marketing de Bourgogne, CERMAB, Dijon, France, 8–9 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lumsdon, L.M.; McGrath, P. Developing a conceptual framework for slow travel: A grounded theory approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, R. Can Slow Tourism Bring New life to Alpine Regions. In The Tourism and Leisure Industry Shaping the Future; Weirmair, K., Mathies, C., Eds.; Haworth Hospitality Press: Binghamton, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, R. Sustainable Tourism and Policy Implementation: Lessons from Case of Calviá, Spain. Curr. Issue Tour. 2008, 10, 296–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls, J.F.; Tuñon, F.J.; Calero, P.; Ramos, J.M.; Prats, F. Un marco estratégico para fortalecer el sistema económico insular, compatible con la contención del crecimiento turístico en Lanzarote, Life Lanzarote, Cabildo de Lanzarote. 2004, 70p. Available online: http://www.cabildodelanzarote.com/ecotasa/des12.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2018).

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithalm, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and its Implications for Future Research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanovic, D.C.; Rosen, L.D. Measuring service quality in restaurants: An application of the SERVQUAL instrument. Hosp. Res. J. 1994, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gronroos, C. A Service Quality Model and its Marketing Implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1984, 18, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getty, J.M.; Thompson, K.N. The relationship between Quality, Satisfaction, and Recommending Behavior in lodging decisions. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 1995, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Gil, I. Value dimensions, perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty: An investigation of university student’s travel behavior. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.; Stevens, P.; Knutson, B.J. Internationalizing LODGSERV as a Measurement Tool: A Pilot Study. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 1994, 2, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, G.R.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Measuring service quality in the travel and tourism industry. J. Travel Res. 1991, 30, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J.E.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Exploring the quality of the service experience: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Adv. Serv. Mark. Manag. Res. Pract. 1995, 4, 37–61. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlena, W.J.; Holbrook, M.B. The varieties of consumption experience: Comparing two typologies of emotion in consumer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannell, R.C.; Iso-Ahola, S.E. Psychological nature of the leisure and tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1987, 14, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkan, E.; Fanderl, H.; Maffei, K. McKinsey & Company, Designing and Starting up a Customer-Experience Transformation. 2016. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/designing-and-starting-up-a-customer-experience-transformation (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- Planta. Pirámide de Experiencias. 2010. Available online: http://planta18.com/es/piramide-de-experiencias (accessed on 16 March 2018).

- Schmitt, B.H. Customer Experience Management; John Wiley & Sons: Haboken, NJ, USA, 2003; 256p, ISBN 978-0-471-23774-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; HBR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 97–105. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299292969_The_Experience_Economy (accessed on 12 March 2018).

- Valls, J.F. Customer-Centricity: The New Path to Product Innovation and Profitability; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2018; 145p. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, J.; Lumsdon, M.; Robbins, D. Slow travel: Issues for tourism and climate change. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffyn, A. Advocating and Implementing Slow Tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2012, 37, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miretpastor, L.; Peiró-Signes, Á.; Segarra-Oña, M.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J. The slow tourism: An indirect way to protect the environment. In Sustainability, Social Responsibility and Innovations in Tourism and Hospitality; Parsa, H.G., Ed.; Apple Academic Press: Oakville, ON, Canada, 2015; pp. 317–339. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H.; Assaf, A.G.; Baloglu, S. Motivations and Goals of Slow Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2014, 55, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molz, J. Representing pace in tourism mobility’s: Staycations, Slow Travel and The Amazing Race. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2009, 7, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosar, A. Il turismo in Slovenia. Le pagine di Risposte Turismo. 2014. Available online: http://www.risposteturismo.it/Public/lePaginediRT/uno2014_lePaginediRT_A.Gosar.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2018).

- Malta Tourism Authority. Tourism in Malta. Facts and Figures 2016. Report 2017. Available online: http://www.mta.com.mt/research (accessed on 22 April 2018).

- Özdemir, G.; Çelebi, D. Exploring dimensions of slow tourism motivation. Anatolia Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 29, 540–552. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, P.; Sharpley, R. Slow Tourism, Food and Cities: Pace and the Search for the “Good Life”. In Slow Tourism, Food and Cities: Pace and the Search for the Good Life; Clancy, M., Ed.; Routlegde: London, UK, 2017; 248p. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T.; Ypeij, A. Tourism, gender and ethnicity. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2012, 39, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural Tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowford, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability: Development, Globalisation and New Tourism in the Third World, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; p. 448. ISBN 978-1-138-01326-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, N.; Hunn, A.; Mathers, N. Sampling and Sample Size Calculation. The NIHR RDS for the East Midlands, Yorkshire & the Humber. 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mansour_Abdullah_Alshehri/post/How_to_determine_population_and_sample_size_for_a_survey_research/attachment/5aa18dfc4cde266d58902255/AS%3A601990316974080%401520537084240/download/Sampling+Sample+Size+Calculation.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Super Office. Seven Ways to Create a Great Customer Experience Strategy. 2017. Available online: https://www.superoffice.com/blog/customer-experience-strategy/ (accessed on 25 March 2018).

- Oriade, A.; Evan, M. Sustainable and Alternative Tourism. In Research Themes for Tourism; Robinson, P., Heitman, S., Dieke, C., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Duarte, P.A.; Folgado-Fernández, J.A. The contribution of cultural events to the formation of the cognitive and affective images of a tourist destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Região Autónoma da Madeira. Estratégia para o turismo da madeira 2017–2021, Região Autónoma da Madeira. 2016. Available online: https://estrategia.turismodeportugal.pt/sites/default/files/Doc_Estrategico_Turismo_RAM_0.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Slee, B.; Farr, H.; Snowdon, P. The economic impact of alternative types of rural tourism. J. Agric. Econ. 1997, 48, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R. Food, place and authenticity: Local food and the sustainable tourism experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanagustín, M.V.; Moseñe, J.A.; Patiño, M.G. Rural tourism: A sustainable alternative. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Di-Clemente, E.; Campón-Cerro, A.M.; Folgado-Fernández, J.A. The experiential value of slow tourism: A Spanish perspective. In Slow Tourism, Food and Cities; Michael, C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- 50Kazeminia, A.; Hultman, M.; Mostaghel, R. Why pay more for sustainable services? The case of ecotourism. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4992–4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Salvo, P.; Calzatti, V. Slow Tourism: A theoretical framework. In Slow Tourism, Food and Cities. Pace and the Search for the Good Life; Clancy, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 52Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; López-Sánchez, Y. Are tourists really willing to pay more for sustainable destinations? Sustainability 2016, 8, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DREM. Indicadores Estatísticos, Direção Regional de Estatística da Madeira. Available online: https://estatistica.madeira.gov.pt/ (accessed on 12 June 2018).

- SRETC. Estratégia para o Turismo da Madeira, 2017-2021, Secretaria Regional da Economia, Turismo e Cultura. 2017. Available online: http://www.visitmadeira.pt/Admin/Public/Download.aspx?file=Files%2FFiles%2FVisitMadeira%2FEstudos%2Fj-DOCUMENTO-ESTRATEGICO-2017-21.pdf (accessed on 02 April 2018).

- Jesus, E. Madeira: Developing a new tourism paradigm. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2016, 8, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroco, J.; Bispo, R. Estatística Aplicada às Ciências Sociais e Humanas; Climepsi Editores: Lisbon, Portugal, 2003; 358p, ISBN 927-769-065-0. [Google Scholar]

- RIS3-RAM. Madeira 2020 Estratégia Regional de Especialização Inteligente RIS3, Agência Regional para o Desenvolvimento da Investigação, Tecnologia e Inovação (ARDITI). 2014. Available online: https://www.portugal2020.pt/Portal2020/Media/Default/Docs/EstrategiasEInteligente/EREI%20Madeira.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- DETRAM. Documento Estratégico para o Turismo na RAM (2015–2020), ACIF, KPMG. Available online: http://estrategia.turismodeportugal.pt/sites/default/files/Doc_Estrategico_Turismo_RAM_0.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2016).

- Buckley, R. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broggi, M. Sanfter tourismus: Schlagwort oder Chance fur den Alpenraum. In Le Tourismedoux, Slogan Oubienfait Pour L’espacealpin? Broggi, M.F., Übers, Chappuis, J., Eds.; Commission Internationale pour las Protection des Regions Alpines: Chur, Switzerland, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Brum da Silveira, A.; Madeira, J.; Ramalho, R.; Fonseca, P.; Prada, S. Notícia explicativa da Carta Geológica da Madeira, na escala 1:50.000, Folhas (A) e (B); Secretaria Regional do Ambiente e Recursos Naturais, Região Autónoma da Madeira; Universidade da Madeira: Funchal, Portugal, 2010; 47p, ISBN 978-972-98405-2-4. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Tourism Statistics; 2016 ed.; European Union Publications: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FundacióGadeso. El Turisme a les Illes Baleares Anuari 2016; FundacióGadeso: Palma, Spain, 2017; 259p. [Google Scholar]

- Gran Canaria Tourist office. Situation of the Tourism Sector-Annual Report; Cabildo de Gran Canaria: Gran Canaria, Spain, 2015.

- Hall, C. Introduction: Culinary tourism and regional development: From slow food to slow tourism? Tour. Rev. Int. 2006, 9, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitman, S. Authenticity in Tourism. In Research Themes for Tourism; Robinson, P., Heitman, S., Dieke, P., Eds.; CABI International: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Insee. Bilan annuel du tourisme-2016. Insee Dossier Corse. Available online: http://www.corsica-pro.com/fr/observatoire/etudes/chiffres-cles (accessed on 22 June 2018).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Estatísticas do Turismo 2017. ISBN 978-989-25-0447-6. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=2ahUKEwiyyNmy2YHkAhXFBKYKHY6xAe4QFjAAegQIABAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ine.pt%2Fngt_server%2Fattachfileu.jsp%3Flook_parentBoui%3D337818965%26att_display%3Dn%26att_download%3Dy&usg=AOvVaw14uqh3XOjg-bOEveAQntU_ (accessed on 22 April 2018).

- Jesus, E. Madeira tourism strategy: How to re-qualify a destination. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorf, J. The Holidaymakers: Understanding the Impact of Leisure Travel; Butterworth Heinemann: London, UK, 1987; 160p, ISBN 978-075-06-4348-1. [Google Scholar]

- Markwell, K.; Fullagar, S.; Wilson, E. Reflecting upon slow travel and tourism experiences. In Slow Tourism: Experiences and Mobilities; Fullagar, S., Markwell, K., Wilson, E., Eds.; Channel View: Bristol, UK, 2012; pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. Experiencia de marca. In En Clave de Marcas; Brujó, G., Ed.; Lid editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2010; 344p. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, C. Challenges of sustainable tourism development in the developing world: The case of Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTTC. Travel & Tourism Economic Impact, Cyprus; World Travel & Tourism Council: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zlatareva, N. Alternative and Mass Tourism Combination Analysis in South Europe. Young Scientist USA; Lulu Press: Auburn, WA, USA, 2015; Volume 2, p. 40. Available online: www.youngscientistusa.com/archive/2/222/ (accessed on 25 March 2018).

| Attributes | Authors |

|---|---|

| Change in the concept of travel and the use of time during the trip | [1,3,7,8,14,35,36,38,39,41,42] |

| Alternative of mass Tourism | [4,6,7,40,43,44,45] |

| Local | [1,2,15,35,36,46,47,48,49,50] |

| Cultural | [15,35,37,51] |

| Sustainable and natural environment | [2,6,8,9,16,34,39,46,52,53,54] |

| Change in the quality of the experience | [11,12,29,34,35,55] |

| Authenticity | [1,2,15,36,56] |

| Feasibility and new business development | [35,57] |

| Study Group | Madeira Autonomous Region | Canary Islands | Cape Verde | Mallorca | Corsica | Cyprus | Azores Autonomous Region | Malta | Sicily |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of tourists | 1.435.700 a,b | 14.980.000 | 716.775 a,b | 10.920.237 | 7.730.000 | 3.652.073 | 594.300 a,b | 1.988.447 | 13.495.491 i |

| Km2 | 801 | 7.493 | 4.033 | 3.640 | 8.680 | 9.251 | 2.346 | 316 | 25.711 |

| Average occupancy rate | 71,4% c 78,4% a,j | 69% a,f | 79,50% | 48,80% | 71,3% c | 50,9% a,c 62,2% a,j | 64,50% | ||

| No. of hotel rooms | 8.498 a | 9.541 a | 81.216 | 12 517 | 41 080 | ||||

| No. of hotel beds | 29.118 | 235.313 | 15.872 a | 155.021 | 756.500 d | 55.202 a | 9.184 a | 33.147 | 121.032 |

| Seasonality months (months with more than 75% occupancy in hotels) | Jul-Set f,h | Ago a,k | Jun-Set i | Ago e Set | Mai-Out e | Jul-Ago a | Jul-Ago a | ||

| Months of Seasonality (months with more than 50% occupancy in hotels) | Jan-Nov f | Mar-Nov a,k | Fev-Nov | Mai-Out | Mai-Out e | Abr-Set a | Mar-Nov a | ||

| Number of residents | 254.876 | 2.108.121 a | 539.56 | 402.949 | 330.354 g | 1.170.000 | 245.283 | 436.947 | 5.056.641 a |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valls, J.-F.; Mota, L.; Vieira, S.C.F.; Santos, R. Opportunities for Slow Tourism in Madeira. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4534. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174534

Valls J-F, Mota L, Vieira SCF, Santos R. Opportunities for Slow Tourism in Madeira. Sustainability. 2019; 11(17):4534. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174534

Chicago/Turabian StyleValls, Josep-Francesc, Luís Mota, Sara Cristina Freitas Vieira, and Rossana Santos. 2019. "Opportunities for Slow Tourism in Madeira" Sustainability 11, no. 17: 4534. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174534

APA StyleValls, J.-F., Mota, L., Vieira, S. C. F., & Santos, R. (2019). Opportunities for Slow Tourism in Madeira. Sustainability, 11(17), 4534. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174534