Affective Sustainability. The Creation and Transmission of Affect through an Educative Process: An Instrument for the Construction of more Sustainable Citizens

Abstract

:1. Introduction

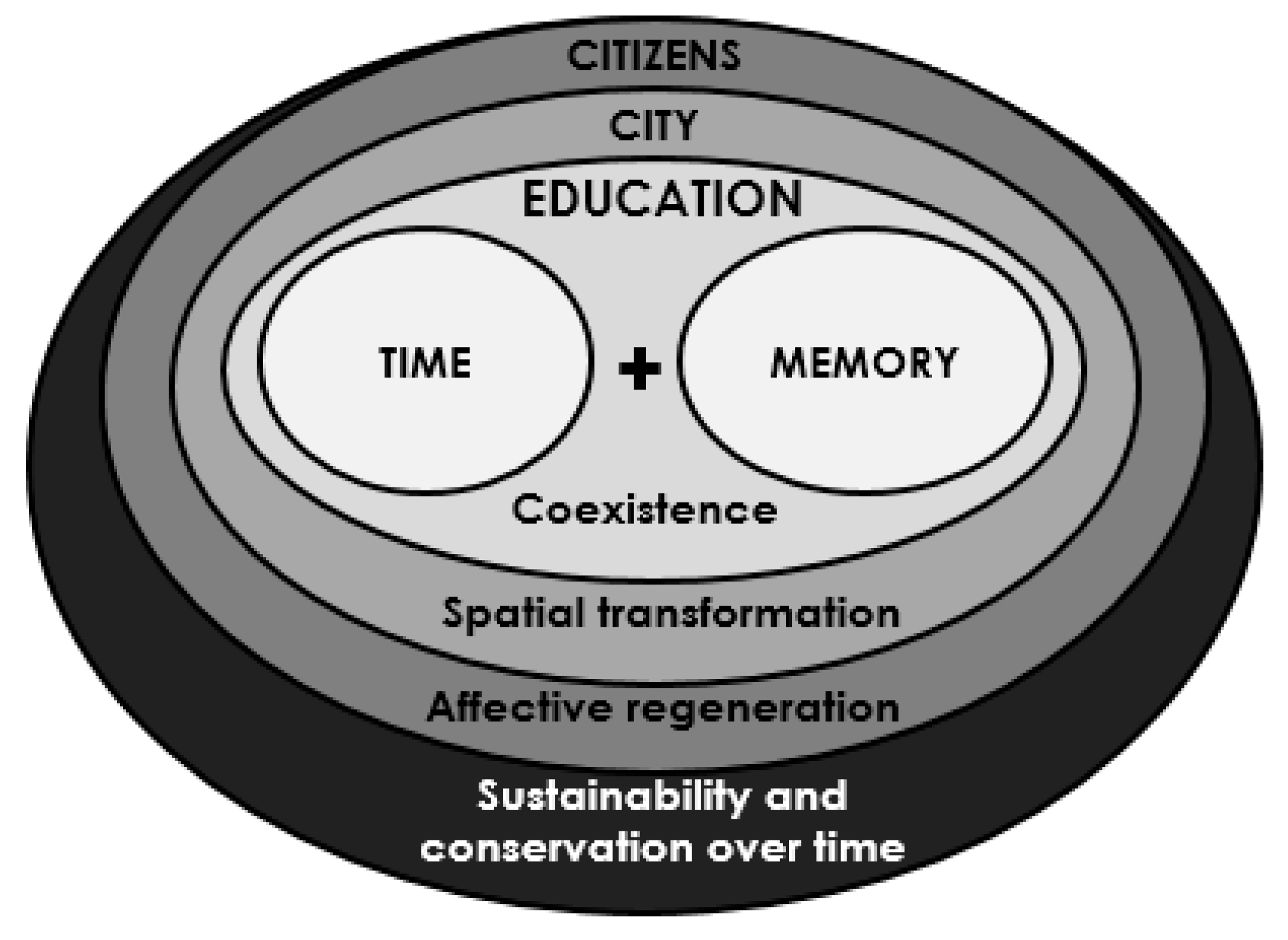

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Current Starting Point: Sustainable and Educational Cities

“as the key instrument, capable of achieving that each person will be aware of their potential, their creativity and their responsibilities towards the physical and urban environment where they live, and all this without forgetting the role and responsibility that public and political institutions possess in said process”.[15]

2.2. Education and Sustainability: Generating Critical Thinking: Improving Inhabitants for Improving Cities

“The challenge of urbanism nowadays comprises raising this other look, that of the urbanism of affection, in very few cases achieved, in others lost and in the majority ignored. This look which recovers in cities the next scale, that of day-to-day living and creates spaces, and an adequate physical environment where there is room for other spaces, emotional ones. It is a case of providing a new perspective, a new approach, which changes the scale of values, because only human ones justify urban ones”.[18]

2.3. Education as an Instrument for Creating Affection: Memory and Time

The true name of any transforming education is that it is humanizing. It will then be liberating to the extent that it triggers, accompanies and challenges learning about the human condition (…) The human condition refers insurmountably to love, which, because of it and in it, is what makes humans what we are.[47]

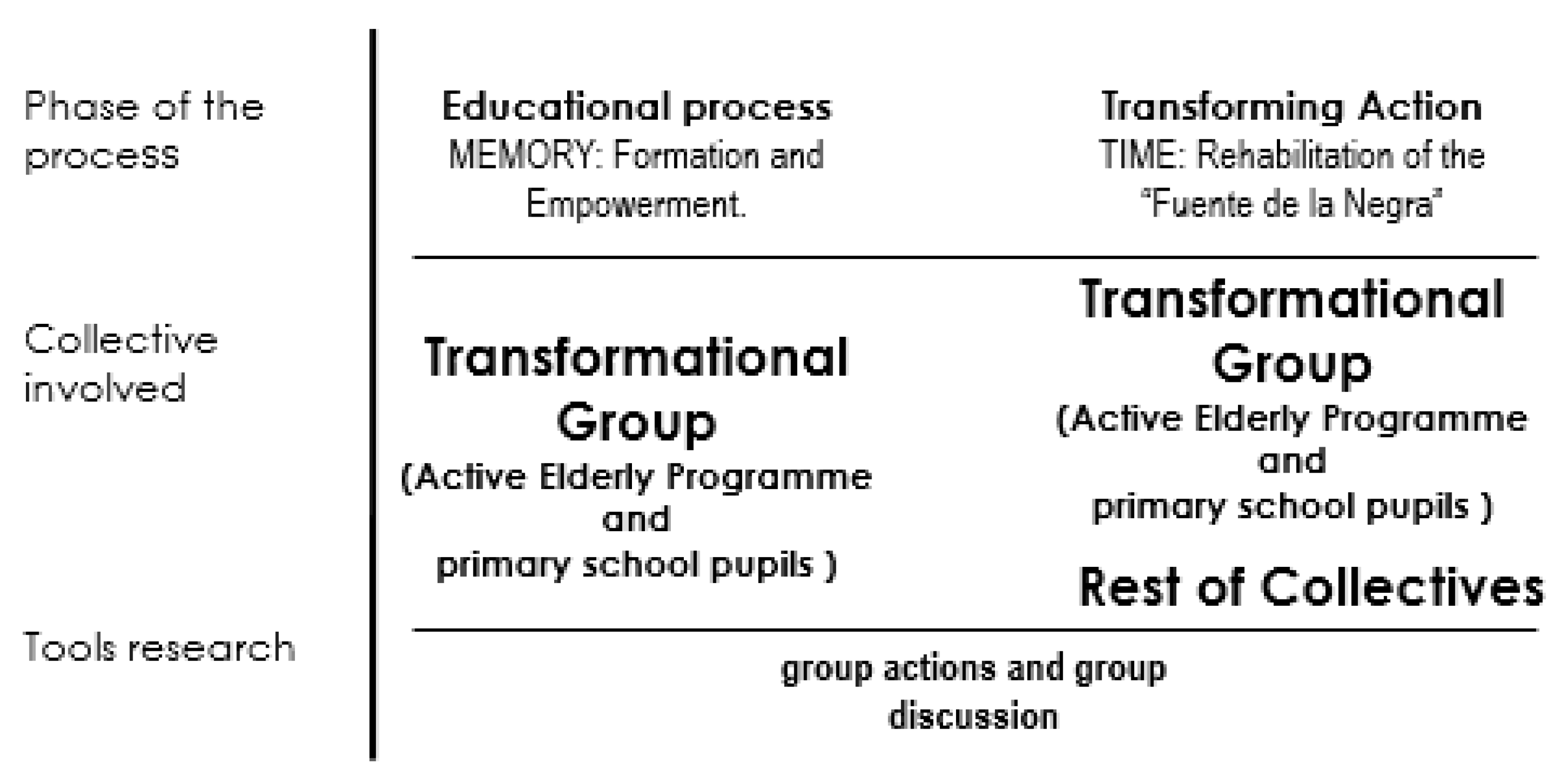

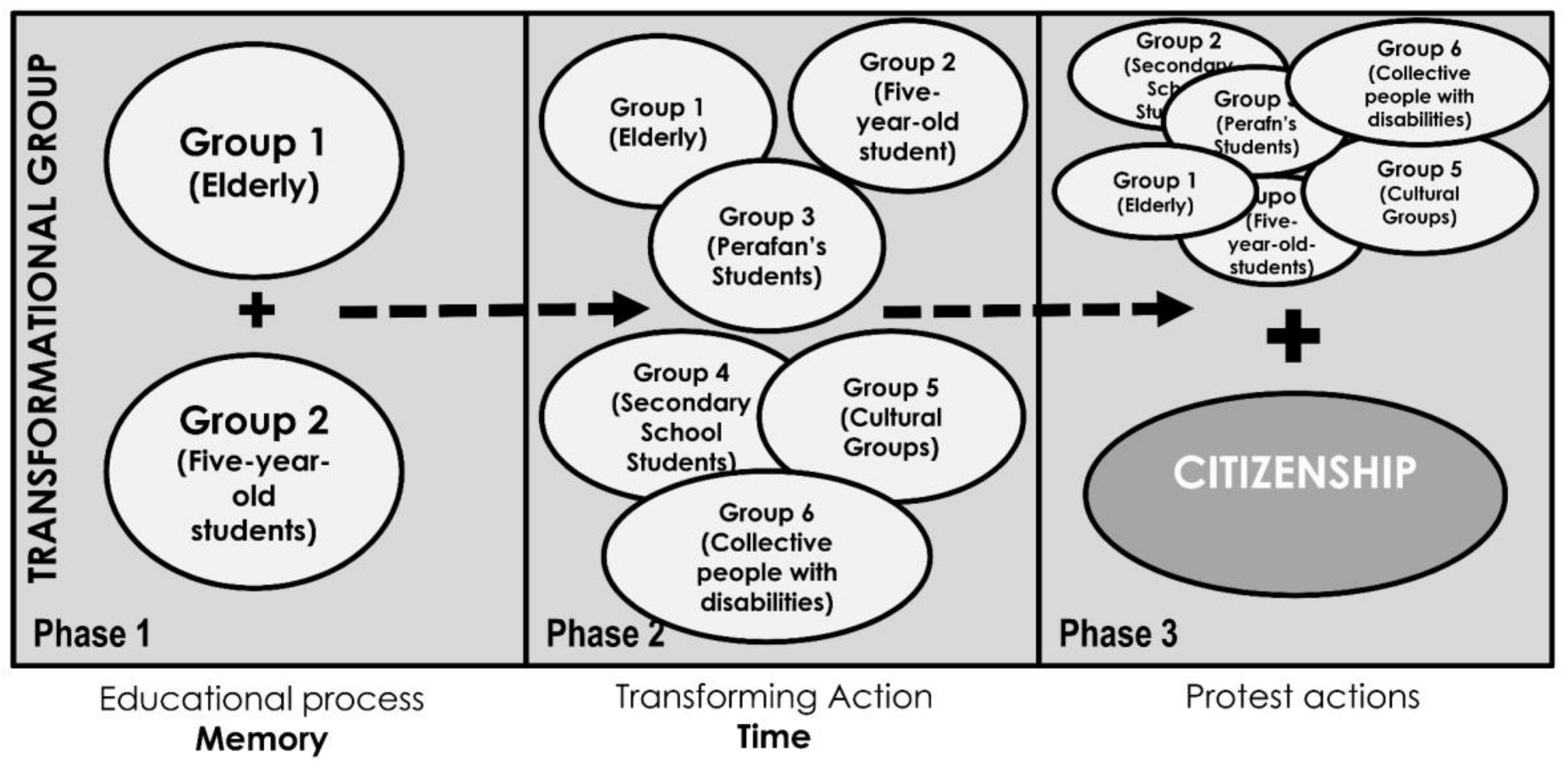

3. Materials and Methods

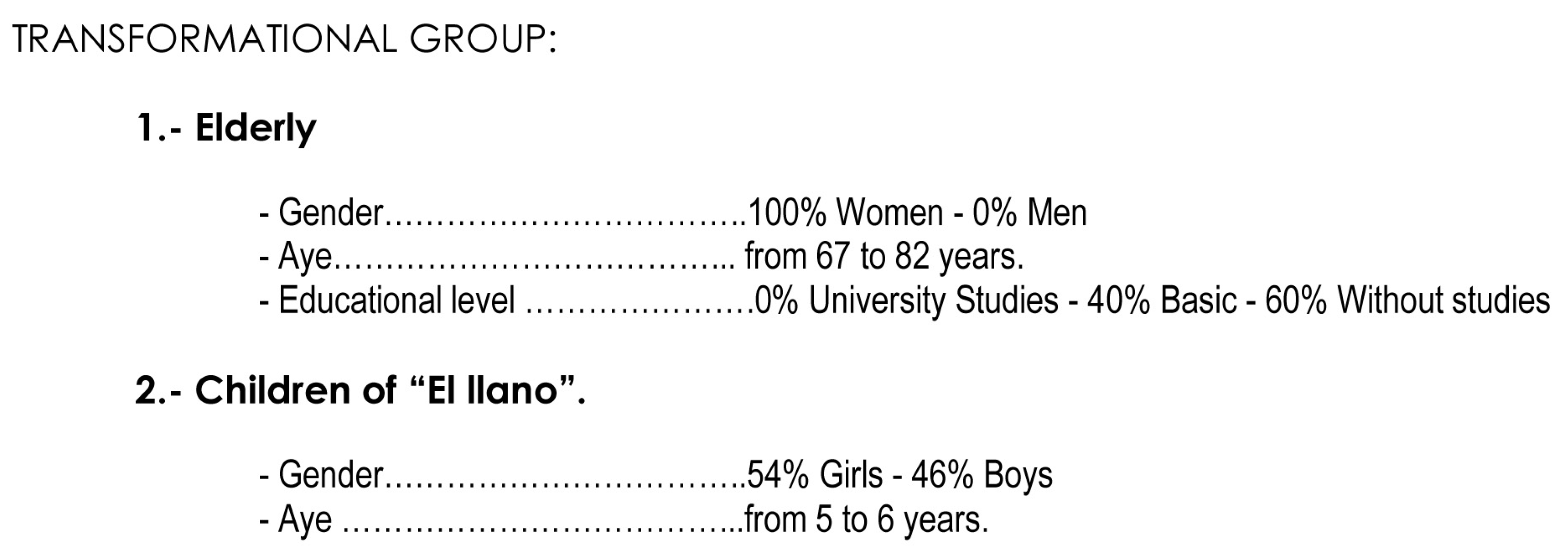

3.1. Location and Groups Involved in the Project

- The “elderly adult” group included in the program “the Active Elderly” in Paterna also belonging to Cádiz County Council, which included women between the ages of 65 and 85 years.

- The group of five-year-old boys and girls from the state primary school “el Llano” in this locality.

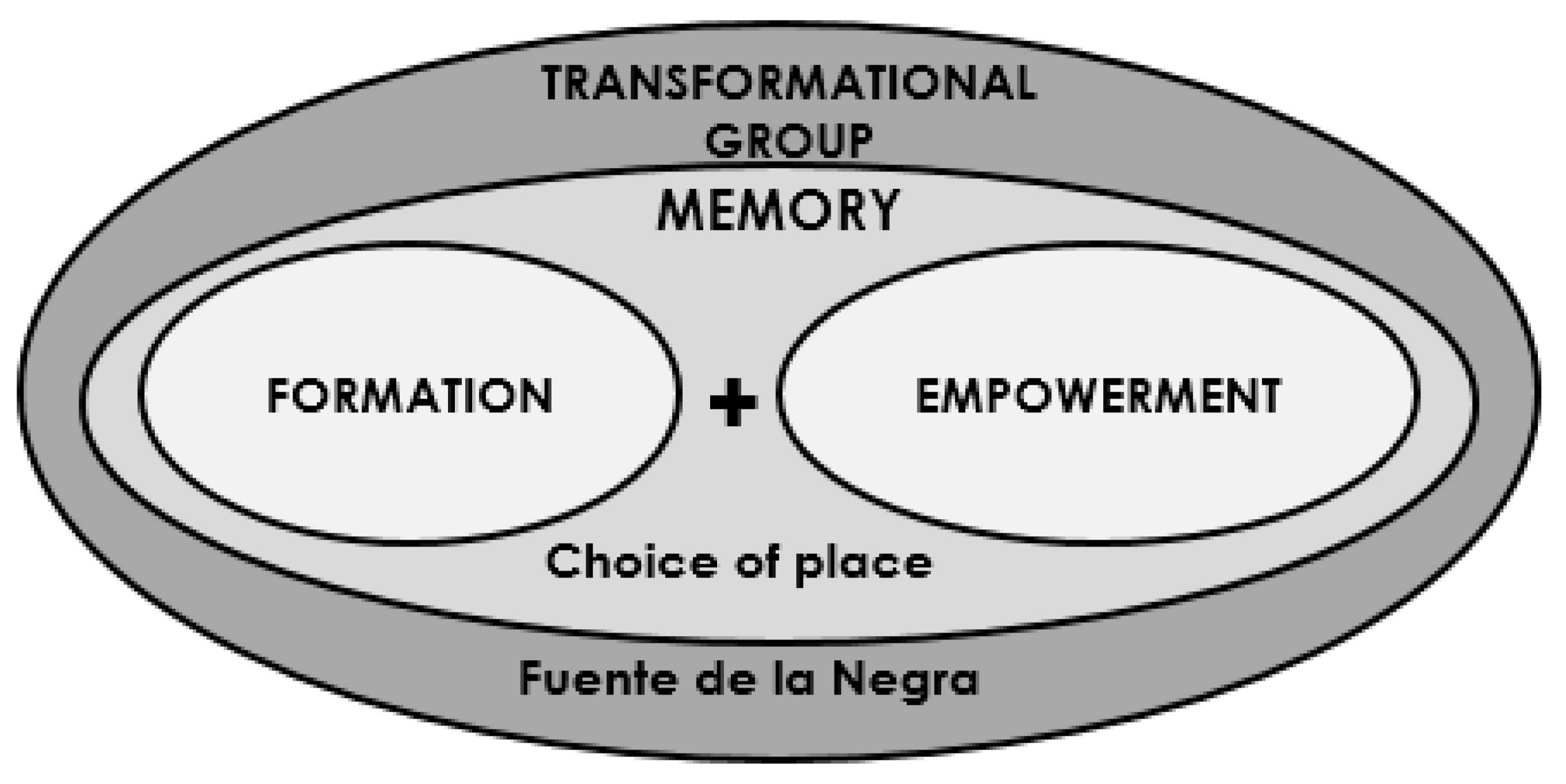

3.2. Memory: Theoretical Definition of the Work Methodology—Education that Transforms and Creates Critical Scrutiny

- 23 September 2016: First project session in which, by means of their dynamics and various training actions, work was undertaken on the perception each one of them had of the village and issues were introduced relating to a possibly more sustainable development of the locality. Besides all this, possible places of interest were identified within the municipality which, from their point of view; could or should be improved from a sustainable and participatory point of view, as can be checked in Figure 9.

- 30 September 2016: Second project session in which by means of their dynamics and various training actions, work was undertaken on making each of the participants aware of the influence and capability they had for improving the environmental, social and urban degradation that existed in their locality by emphasizing the various potentialities and possibilities that all of them had for improving them.

- 7 October 2016: With the collaboration of a specialist entity, the place to be acted upon decided by the participants was visited. This was called Fuente de la Negra, and work was done on concepts linked to sustainability, such as xeroscaping or permaculture, besides starting to generate ideas about what the modifications to be carried out could be in order to improve this area.

- 14 October 2016: Fourth project session in which, by means of their dynamics and various training actions, and thanks to the reflections made in the previous session, the participants drew up several proposals for projects to improve and modify the area called Fuente de la Negra.

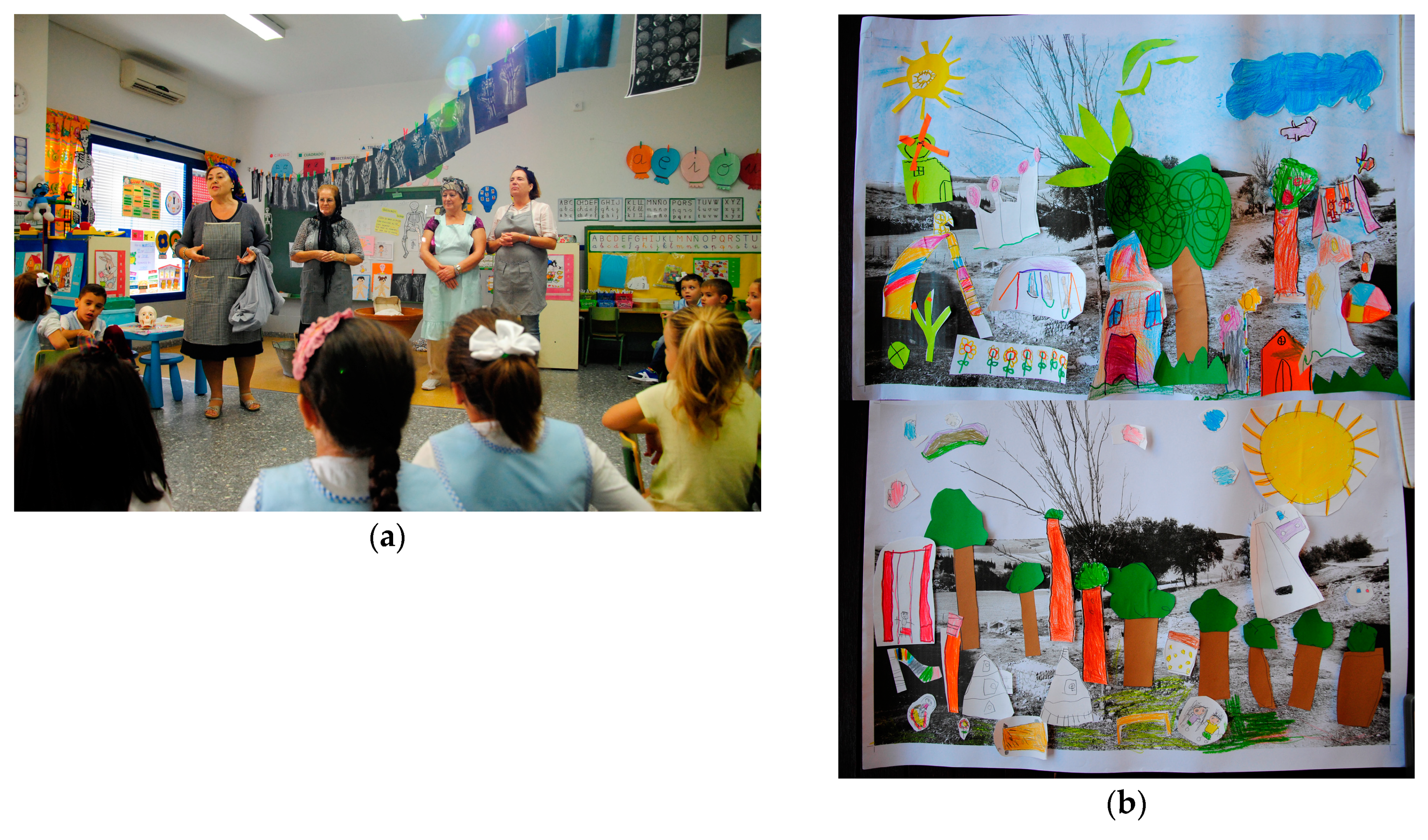

- 19 October 2016: Intergenerational session. Once the proposal had been drawn up and they had been made aware of its potential to change Paterna, a session was held with three classes of third-year primary school children from El Llano Primary School in the village. As can be seen in Figure 10a in this session our participants not only explained the importance of the place they had chosen, but were also part of the process of getting the pupils to generate new ideas and proposals to improve the area in question (Figure 10b).

- 29 October 2016: Preparation session for material to be used in the final project session. Together with several volunteers, as well as representatives of the Active Elderly group and the Secondary School in Paterna, the Ítaca staff prepared throughout the whole day the various materials which would be used in the participatory action on Monday 31, for the improvement of the Fuente de la Negra area.

3.3. Time: Description of the Real Action for Change—The Case of Restoration of the Fuente de la Negra Park

- Clearing and removing rubbish from the area;

- Building and installing urban furniture;

- Painting an artistic mural;

- Creating posters and new signage for the place;

- Planting of shrubs and aromatic plants;

- Reforestation;

- Organizing leisure activities (community meal).

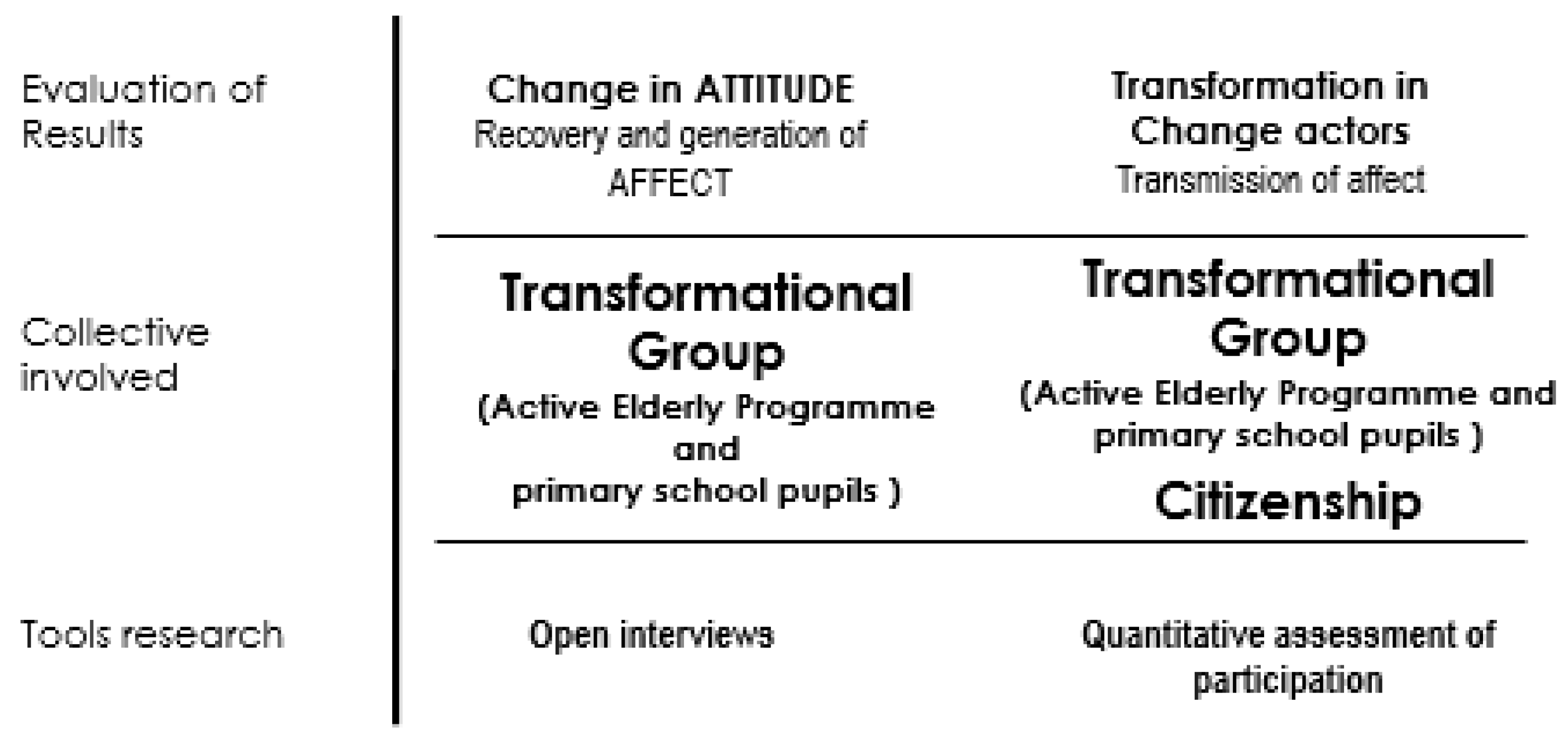

4. Results

4.1. General Results: Evaluation of the Affectivity Increase and Involvement Level in Environmental Improvement (Qualitative Research)

- The majority affirms that at the beginning of the educational program they already knew the space of La Fuente de la Negra and had visited it;

- Eighty-seven percent of the interviewees declared that at the beginning of the program they thought that they would not be able to change and improve that space environmentally by their own;

- After the process, they have all brought their memories back and feel attached to that space again;

- All women, in some way, recognize that now they can change and improve things if they believe in their actions;

- All the interviewees are in some way convinced to continue working on improving the space known as La Fuente de la Negra;

- Most of the interviewees stated that what they liked the most about the experience is having been able to remember their youth and their time spent in that space. They advised that having been able to share time together with the children (many of them, their grandchildren) transmits those memories to them.

- At the beginning of the process, nobody knew the space by the name “La Fuente de la Negra”, and most of them had never physically been in that space;

- After the project, 100% of them declare in some way their intention to continue working to improve this space;

- At the end of the process, 100% of the children declare having felt involved and listened to when deciding the actions to be carried out in this space;

- The majority of them declare that the issues that have most satisfied them have been sharing the experience with other children and especially with the elderly women.

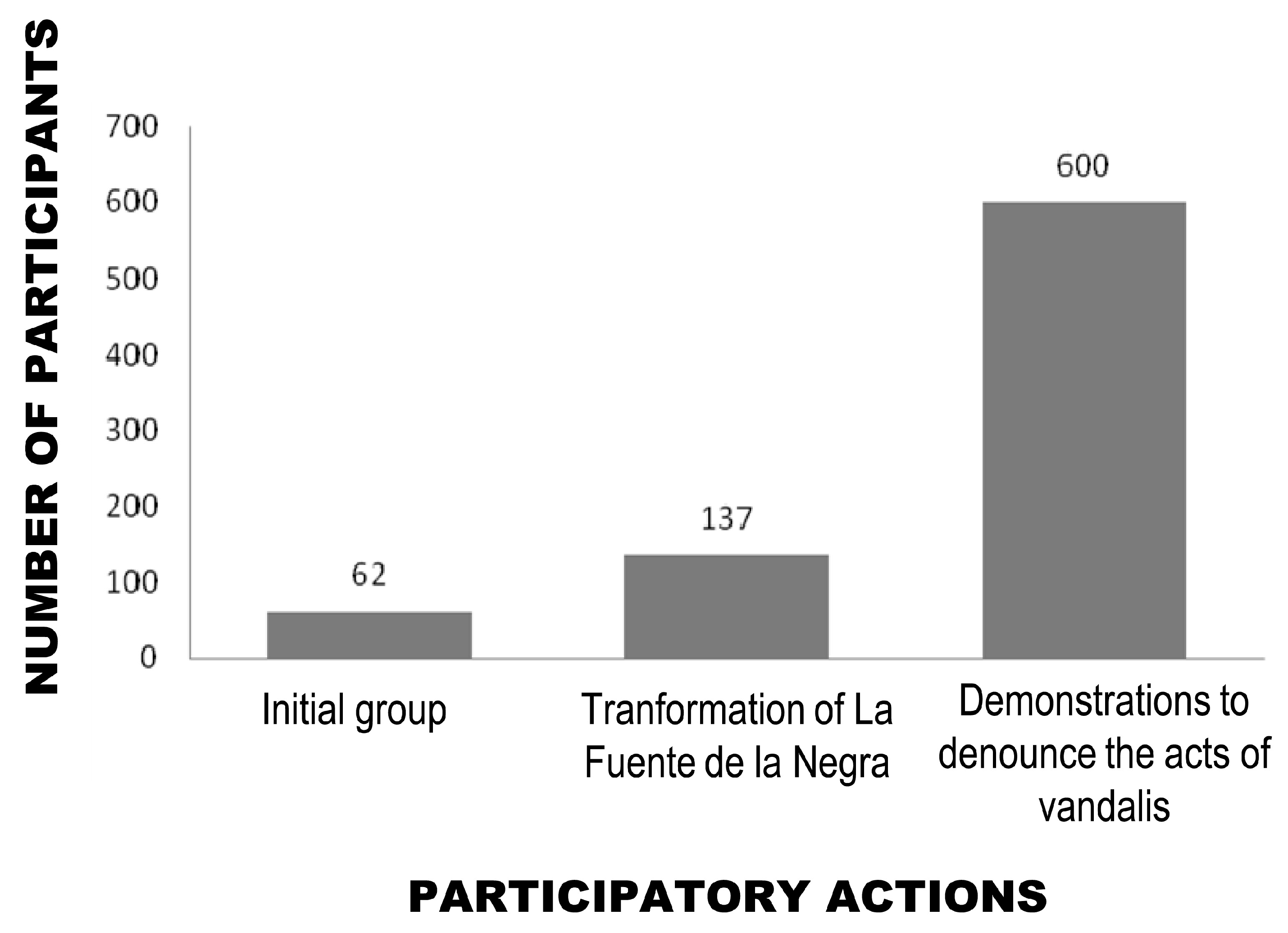

4.2. Transmission of Affection to the Rest of the Groups: Initial Results.

- Fifty primary school pupils;

- Twenty female citizens included in the Active Elderly program;

- Sixty primary school pupils and five teachers from El Llanito School;

- Fifteen female citizens included in the Active Elderly program;

- Twenty-five pupils and three teachers from the CEPR Perefán from Ribera de Paterna;

- Fourteen pupils and two teachers from the State Secondary School in Paterna de Rivera;

- Two members of the cultural group Impresiones;

- Five members of the Paterna Byke Sports Club;

- Six members of the disabled group ASDIPAR.

4.3. Transmission of Affection to the Rest of the Society: Final Results

5. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 1998; ISBN 978-184-112-084-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, T.B.; Caeiro, S.; van Hoof, B.; Lozano, R.; Huisingh, d.; Ceulemans, K. Experiences from the implementation of sustainable development in higher education institutions: Environmental Management for Sustainable Universities. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquert, A. Sostenibilidad afectiva. Bol. CF+ S 2014, 7, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogía de la Esperanza: Un Reencuentro con la Pedagogía del Oprimido; Siglo XXI: Cordova, Argentina, 1993; ISBN 978-968-231-899-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, J. Acupuntura Urbana; Institut d’Arquitectura Avançada de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2005; p. 27. ISBN 84-609-6450-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, B.; Moore, D.; Goldfinger, S.; Oursler, A.; Reed, A.; Wackernagel, M. Ecological Footprint Atlas. 2010. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.660.8339&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 27 November 2018).

- Moran, D.D.; Wackernagel, M.; Kitzes, J.A.; Goldfinger, S.H.; Boutaud, A. Measuring sustainable development-Nation by nation. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, A.; Chapin, F.S., 3rd; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. The origin and growth of urbanization in the world. Am. J. Sociol. 1955, 60, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habitat, U.N. Urbanization and development emerging futures. World Cities Rep. 2016, 3, 4–51. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals Report 2016. UN, 2016. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/news/communications-material/ (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Hábitat, O.N.U. Habitat III issue papers: 11-public space. In Proceedings of the Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development at Quito, Quito, Ecuador, 7–20 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardine Von Irmer, H. Valorizar el espacio viario: Hacia una movilidad sostenible y equitativa. In Revista de Arquitectura; Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo de la Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2011; Volume 17, pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- González Morales, Á.L. Urbanismo educativo y discapacidad: Nuevos mecanismos participativos para una ciudad más sostenible e integradora. El caso del Plan Maestro del Centro Histórico del DC de Honduras. Arquit. Sur 2018, 36, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ciudades Educadoras, Carta. declaración de Barcelona. Principios. 1990. Available online: http://www.edcities.org/en/charter-of-educating-cities/ (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Colom, A. La Pedagogía Urbana, Marco Conceptual de Ciudad Educadora; Ponencia presentada en el I Congreso internacional de Ciudades Educadoras, 1990. En: Aportes, Santafé de Bogotá; Ayuntamiento de Barcelona: Vienna, Austria, 1991; Volume 45, p. 42.

- Banerjee, I. Educational Urbanism-the Strategic Alliance between Educational Planning, Pedagogy and Urban Planning; ISRA-Centre of Sociology, Vienna University of Technology: Vienna, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bisquert, A. El urbanismo de los afectos. In Infancia Urbana y Vida Cotidiana Actas de las Jornadas” los Niños en la Ciudad”: Madrid 25, 26 y 27 de Septiembre de 1996; Ministerio de Fomento: Madrid, Spain, 1997; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social Sustainability: A New Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, N.; Theesfeld, I.; Strassner, C. Social Sustainability through Social Interaction—A National Survey on Community Gardens in Germany. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, F.; Schnack, K. The action competence approach and the ‘new’ discourses of education for sustainable development, competence and quality criteria. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 17 Goals to Transform Our World. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Education for Sustainable Development Goals. Learning Objectives. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002474/247444e.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Habitat, U.N. New Urban Agenda. Quito Declaration on Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements for All; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Asociación Ítaca Ambiente Elegido. Available online: http://itacaambientelegido.wixsite.com/itaca?fbclid=IwAR2THS2BSETCk1cgPSVrBLGwjSYT5iPSlVTClNIWPw7L3o7iK17p3GQmwD8 (accessed on 7 February 2019).

- González Morales, Á.L. Sinergias Afectivas. El Paisaje Como Origen De Un Proceso De Intermediación Ecológico-Cultural. Urbano 2014, 17, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B.; Holden, A. Affective urbanism and the event of hope. Space Cult. 2008, 11, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomery, E.A.; Gibbons, F.X.; Reis-Bergan, M.; Gerrard, M. From willingness to intention: Experience moderates the shift from reactive to reasoned behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 894–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Læssøe, J. Education for sustainable development, participation and socio-cultural change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Certeau, M. La Invención de lo Cotidiano; Universidad Iberoamericana: Mexico City, Mexico, 1996; ISBN 978-968-859-259-5. [Google Scholar]

- Checkoway, B. What is youth participation? Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquert, A. El niño y la Ciudad; COAM: Madrid, Spain, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- González Morales, Á.L. La regeneración urbana como un proceso abierto. Educación y afecto: Nuevos instrumentos para la regeneración de áreas urbanas obsoletas. In En I Jornadas Periferias Urbanas, la Regeneración Integral de Barriadas Residenciales Obsoletas: Libro de Capítulos; Universidad de Sevilla: Seville, Spain, 2017; pp. 484–498. [Google Scholar]

- Disterheft, A.; Caeiro, S.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Leal Filho, W. Sustainable universities: A study of critical success factors for participatory approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imen, P. Trabajo Docente: Debates Sobre Autonomía Laboral y Democratización de la Cultura. Políticas Educativas y Trabajo Docente: Nuevas Regularidades, Nuevos Sujetos? Noveduc: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2006; ISBN 987-538-181-0. [Google Scholar]

- Schafersman, S.D. An Introduction to Critical Thinking. 1991. Available online: http://facultycenter.ischool.syr.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Critical-Thinking.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2019).

- Paredes-Labra, J.; Siri, I.; Oliveira, A. Preparing Public Pedagogies with ICT: The Case of Pesticides and Popular Education in Brazil. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, M. Educação ambiental crítica. In Identidades da Educação Ambiental Brasileira; Secretaria, E., Diretoria de Educação, A., Eds.; MMA: Brasilia, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Leff, E. Epistemologia Ambiental, 3rd ed.; Cortez: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Uzcátegui, Y. La salud. Un derecho humano por construir desde la educación. Educere 2014, 18, 399–408. [Google Scholar]

- European Council. The Paris Declaration on Promoting Citizenship and the Common Values of Freedom, Tolerance and Non-Discrimination through Education; European Council: Strasbourg, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Driel, B.; Darmody, M.; Kerzil, J. Education Policies and Practices to Foster Tolerance, Respect for Diversity and Civic Responsibility in Children and Young People in the EU; NESET II Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hazelkorn, E.; Ryan, C.; Beernaert, Y.; Constantinou, C.P.; Deca, L.; Grangeat, M.; Karikorpi, M.; Lazoudis, A.; Casulleras, R.P.; Welzel-Breuer, M. Report to the European Commission of the Expert Group on Science Education, Science Education for Responsible Citizenship; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, J.; Lubben, F.; Hogarth, S. Bringing Science to Life: A Synthesis of the Research Evidence on the Effects of Context-Based and STS Approaches to Science Teaching. Sci. Educ. 2007, 91, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttiroiko, A.V. City-as-a-Platform: The Rise of Participatory Innovation Platforms in Finnish Cities. Sustainability 2016, 8, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cussianovich, A. Aprender la Condición Humana. Ensayo Sobre Pedagogía de la Ternura; IFEJANT: Lima, Peru, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogía del Oprimido; Siglo XXI: Cordova, Argentina, 2005; ISBN 978-843-230-184-1. [Google Scholar]

- Streck, D.R.; Redin, E.; Zitkoski, J. (Eds.) Dicionário Paulo Freire; Autêntica: Lima, Peru, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R. El Sentido de lo Humano; JC Sáez Editor: Santiago, Chile, 2005; ISBN 978-956-780-234-0. [Google Scholar]

- Toro, R. Afectividade. Apostila da escola de Formacao. In International Biocentric Foundation; Biodanza; Editora Olavobras/EPB: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Vecchia, A.M. Educação e afetividade. Revista Pedagógica 2017, 4, 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F. Conexões Ocultas, as; Editora Cultrix: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti, K.B. Pedagogia Vivencial Humanescente; UFRN: Natal, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boff, L.; Valverde, J. El Cuidado Esencialética de lo Humano, Compasión por la Tierra; Editorial Trotta: Madrid, Spain, 2002; ISBN 978-848-164-517-0. [Google Scholar]

- Boff, L. Paulo Freire y los valores de un nuevo milenio. In Figuras y Pasajes de la Complejidad en la Educación; Instituto Paulo Freire de España y Ediciones CREC: Valencia, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R.; Verden-Zöller, G. Amor y Juego: Fundamentos Olvidados de lo Humano, Desde el Patriarcado a la Democracia; JC Sáez Editor: Santiago, Chile, 2003; ISBN 978-956-780-252-4. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González Morales, A.L. Affective Sustainability. The Creation and Transmission of Affect through an Educative Process: An Instrument for the Construction of more Sustainable Citizens. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154125

González Morales AL. Affective Sustainability. The Creation and Transmission of Affect through an Educative Process: An Instrument for the Construction of more Sustainable Citizens. Sustainability. 2019; 11(15):4125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154125

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález Morales, Angel L. 2019. "Affective Sustainability. The Creation and Transmission of Affect through an Educative Process: An Instrument for the Construction of more Sustainable Citizens" Sustainability 11, no. 15: 4125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154125

APA StyleGonzález Morales, A. L. (2019). Affective Sustainability. The Creation and Transmission of Affect through an Educative Process: An Instrument for the Construction of more Sustainable Citizens. Sustainability, 11(15), 4125. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154125