1. Introduction

In Canada, the US, the UK, and elsewhere, school curricula are being reformulated to include 21st century learning competencies [

1,

2,

3]. In the last decade, numerous reports, whitepapers, and well-organized and well-funded education initiatives launched by non-governmental and not-for- profit organizations have appeared with the express purpose to reconceptualize education for the 21st century. These initiatives have come to be known generically as 21st century teaching and learning. Some of these initiatives represent partnerships between school districts, government departments, and education ministries with large multinational corporations, to shift education priorities to new learning goals and disrupt deeply embedded education structures initiated over a hundred years ago that are still foundational to current education practice [

4,

5,

6].

While diverse authors, reports, and agencies emphasize different skills, knowledge, and dispositions over others, most agree on the four C’s of 21st century learning: Critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creative problem solving. To those four, Fullan and Langworthy [

6] add character education and citizenship while others may specifically include culture, global awareness, agility, and adaptability, as well as computer and digital technologies. There is an international consensus coalescing around the skills, competencies, knowledge, beliefs, and dispositions it is believed young people will need to meet the challenges the world will face in the coming decades. Corporations, specifically technology companies, have been very active in promoting the need for 21st century learning as they understand workplaces, present and future, will require employees adept at systems and design thinking, collaboration, creative problem solving, communication, and logical reasoning [

6,

7]. Corporations are interested in developing future employees. As the corporations of the 19th and 20th centuries inserted themselves into school systems to train the workforce they required for manufacturing, so too do the corporations of today have a vested interest in education and are working to influence what happens in schools. These trends can be worrisome as corporations and venture capitalists begin to see investments in 21st century and innovative K12 schooling models as “financial and not philanthropic” [

7] (p. 130), [

8].

In addition to 21st century learning initiatives there have been other international efforts to reform education to better equip future generations to meet the challenges posed by issues of equity, social justice, and environmental degradation facing communities around the world. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) strives for greater equity between individuals and groups, realized through values related to social justice, poverty reduction, and systems thinking. ESD represents environmental, economic, and social interests as being inextricably intertwined and was born out of the Earth Summit in 1992 [

9,

10]. Chapter 36 of the

Agenda 21 document that was developed through the Earth Summit presented a vision of the world’s education systems educating in ways that would lead to a more sustainable future. ESD, or Education for Sustainability (EfS) as it is also generally known in Canada, has emerged as an approach to teaching and learning that is locally relevant, culturally appropriate, and addresses the pillars of sustainability (environment, society, economy). In this regard, EfS is action-oriented and promotes similar competencies as 21st century learning, as described above, but learning with an overarching vision, “to help communities and countries meet their sustainability goals and attend to the well-being of the planet and all its living inhabitants” [

9] (p. 7). EfS has emerged as an inclusive approach to connecting environmental education to the interconnected issues related to social and economic issues that impact individual and community well-being. The academic resistance to EfS, specifically in the environmental education field, over the past three decades has been well documented elsewhere [

9,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. David Orr best captures the current state of the ongoing tensions by calling for a transition to “a new post sustainability and environmental education. Their common aim… is to build a far better world that begins in clarity of mind, compassion, dedication and stamina to endure…” [

16] (p. x).

In 2015, the United Nations published Resolution 70/1

Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 targets call for deep commitment to 21st century competencies and a creativity-intense, technology enhanced re-design of the purposes and approaches to education. The goals and targets represent a “supremely ambitious and transformational vision” [

17] (p. 7) and require all segments of civil society and stakeholders to re-imagine how we will meet the challenges before us. This call is particularly relevant to those in education and quickens the mission of those who are working to transform how we currently organize K12 public education. The UN 2030 Agenda [

17] questions how such a transition can be managed, the leadership that will be required to facilitate the reforms, and how to ensure that 21st century competencies align with sustainability exigencies.

In this paper, a coherent vision of education for sustainability and well-being is introduced. It is a vision that integrates 21st century competencies and a holistic approach to K12 education called the Living School—a concept that is central to an emerging transformative sustainability education paradigm [

18]. Additionally, in keeping with the ethos of ecological thinking and the interdependence of communities, the values of local relevance, and cultural appropriateness, an approach to scalable educational change through sustainable community economic development (CED) is offered. We argue this approach to education reform reflects the principles and values of sustainability by situating schools as important partners in developing sustainable community economic development and well-being. To illustrate the innovative 21st century learning that reflects sustainability and well-being, we offer a brief description of individual schools in Canada and the U.S. that, to varying degrees, embody the principles of a Living School and may be referred to as “pockets of excellence.”

We then posit that transformative educational change [

19,

20] that is scalable, and not simply relegated to these pockets of excellence, requires enlightened, skilled leadership. It is leadership that demonstrates specific competencies in governance and policymaking, creates powerful community coalitions, facilitates the creation of a shared vision for change, and communicates that vision to the public. It is argued that transformative educational change through community coalitions can be realized by adopting the principles of Community Economic Development (CED) that are re-conceptualized and closely aligned with the Living School concept. Transformative educational change that is scalable can only occur when schools are connected to community. School leadership that seeks to integrate the school into the social and economic life of the community build partnerships to fundamentally transform schooling to enhance learning, engagement, well-being, and a deeper sense of schools as integral to larger community ecosystems.

Finally, we outline briefly a blueprint for developing skilled leaders of transformative educational change. A type of advanced professional learning is proposed. It is professional learning for education leaders and prospective leaders who will be able to link K12 and post-secondary education with political, municipal, business, non-governmental organizations, and higher education in a holistic, integrated approach to sustainable community development. Leaders with the administrative and governance skills to facilitate dialogue that is future and action oriented, infused with the energy of youth and the well-being of communities are central to implementing lasting transformative educational change. These are aspirational goals that can unite people in a common purpose: To transform education and connect schools with communities in promoting sustainable growth and well-being for all.

2. A Coherent Vision: Living Schools for 21st Century Learning

Much has been written of the inability of nineteenth and twentieth century education structures, approaches, and pedagogies to meet the demands of twenty-first century realities [

21,

22,

23]). However, as societal norms and technologies continue to shift, the inability of current educational models to respond becomes ever more apparent. There is an urgent need to address the limitations of K12 education [

5,

10]. Despite the pockets of excellence and transformative teaching and learning happening in schools today, the fundamental pedagogical structures of how we organize education have proven to be deeply resistant to transformation and have remained virtually unchanged for over a century. Entering the nineteenth year of the twenty-first century without having realized substantive, scalable transformation further reflects the pedantic nature of our current educational structures and learning environments.

Reforms developed by individual schools, motivated teachers, and administrators have been associated with transformational success and provide models and inspiration for others. However, without the necessary leadership, school board, provincial and state policy, and resource supports, sustaining the reforms requires inordinate effort and commitment on the part of schools. Furthermore, the changes may not last, and tend to wane or disappear altogether when key people leave the school. Likewise, reform implemented externally by school districts, ministries, or state departments of education may be easier to implement, resource, and disseminate across large numbers of schools, however, simply imposing change from above is not enough to disrupt established norms to create enduring, structural reform.

Hopkins [

24] has proposed a repurposing of education with a vision of well-being for all, sustainably. This vision incorporates 21st century competencies with a clear mandate to consider how existing structures and assumptions about education contribute to, or detract from, individual and collective well-being, and indeed the well-being of all life on the planet—now and into the future. Living Schools offer a conceptual framework for realizing this vision and poses the question, “What does education look like when ‘life’ is central to the enterprise?”

Living schools are predicated on a deep sense of meaningful contact with others and the larger living world that fundamentally carries our lives forward. In advocating a sense of reverence for life, education in a Living School offers a transformative mode of thinking that cultivates compassion. The curriculum of the Living School is one founded on understanding the vitality of one’s place within the larger living landscape as being inextricable from human well-being.

O’Brien and Howard (2016) offer a Living Schools conceptual framework designed as a learning and change process [

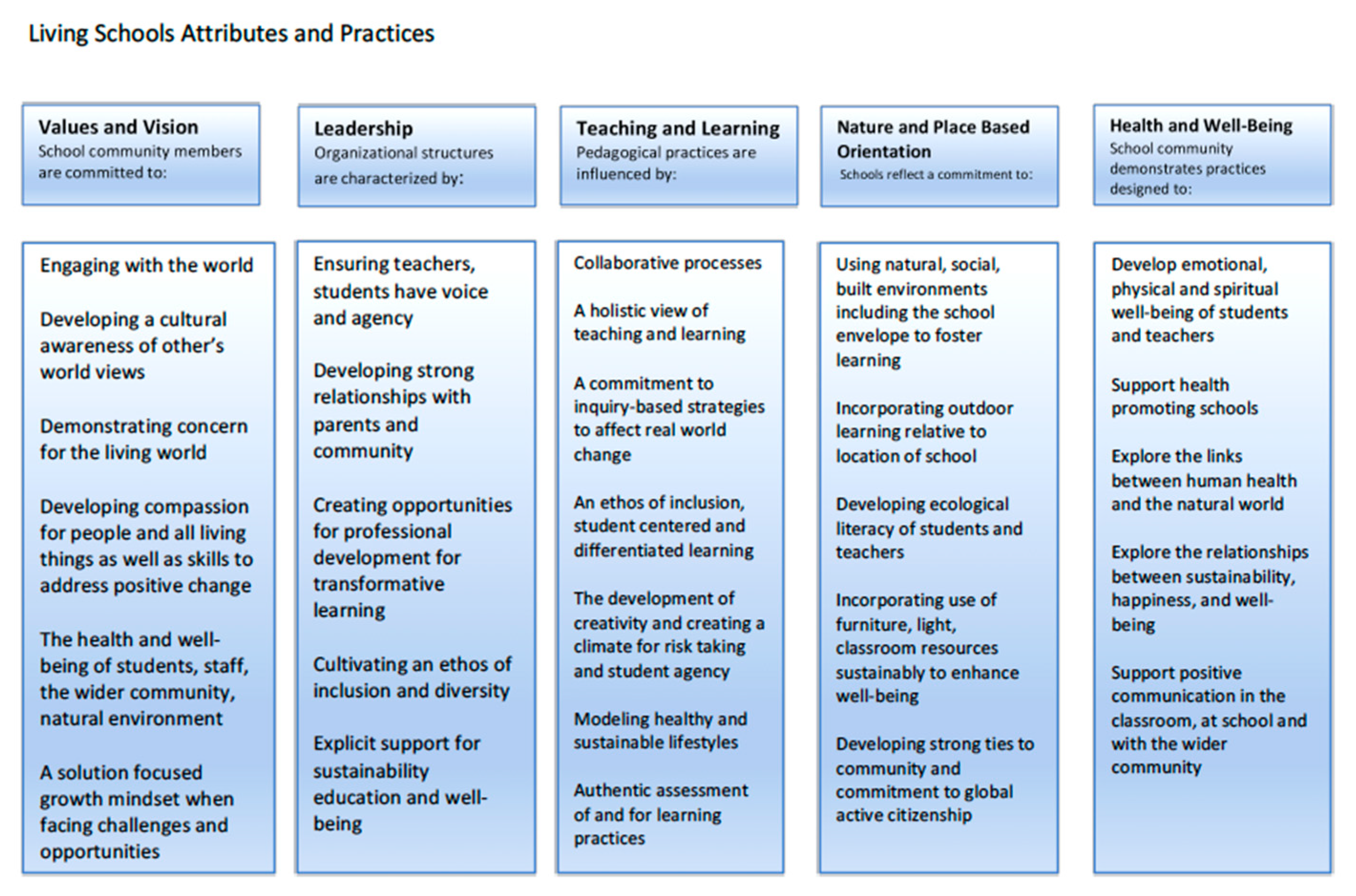

18]. The concept recognized that many of the practices and attributes (see

Figure 1) that reflect a Living Schools ethos are already happening in many schools to varying degrees. A Living Schools approach provides a conceptual frame on which to hang many practices, providing a cohesive vision for approaches that may seem disconnected for teachers, students, administrators, and caregivers. The concept also provides a developed educational vision, and attributes across a range of indicators toward which schools can move to more fully realize the Living Schools concept. In practice, this means Living Schools readily embrace 21st century competencies including critical thinking, communication, collaboration, creative problem solving, character education, and citizenship [

6]. Additionally, innovation, creativity, and entrepreneurial mindsets are a hallmark of Living Schools, as well as computer-enhanced learning. The focus on well-being ensures that Living Schools support outdoor learning [

25], social-emotional learning [

26], positive education, and Health Promoting Schools where staff and students flourish [

23,

27,

28]).

A signature quality of Living Schools is that new pedagogies are embraced—along with lessons learned from more ancient traditions. Educators explore the use of emerging pedagogies such as: Project-based and real-world learning, land-based education, flipped learning [

29,

30,

31], yoga, and indigenous ways of learning and knowing. Conventional roles of teachers and students shift, as well as forms of assessment. The chart below portrays the emergent roles of teachers and students with new pedagogies [

32]. Living Schools enhance this further by underscoring the central value of well-being for all, sustainably (

Figure 1).

Previous research [

18] identified several international examples of learning spaces that reflect the Living Schools concept. The Green School Bali and the Barefoot College in India were recognized, though neither of these organizations identify formally as Living Schools. Subsequently, we have investigated schools that reflect the ethos of a Living School and developed a list of attributes and practices [

33]. Educators may recognize some of these attributes and practices as ones that are representative of their classroom or school. Green Schools and Eco Schools, for example, would align with many of the Living Schools attributes. The Center for Green Schools in the US focuses on three areas: Reducing environmental impacts and costs, improving occupants’ health and performance, and increasing environmental and sustainability literacy [

34]. Member schools of the New Pedagogies for Deep Learning (NDPL) clusters [

32] would reflect many elements of Living Schools as well. However, there is little mention of sustainability in published documents about NDPL [

6,

32]. Our aim is to demonstrate a general portrait of what a Living School could represent, affirming that how this is realized will differ across communities, as we will see in the next section.

Living Schools are co-emerging independently and organically around the world. A Living School is planned to open in Australia in 2020 (

http://livingschool.com.au/). The Canadian Living School concept is not conceived as proprietary, but open source with resources available to teachers, parents, and administrators free of charge. Planning is underway to create a community of Living Schools with opportunities for sharing, community building, and research through the website

https://www.livingschools.world/. Schools can avail of the materials and move toward realizing the attributes and practices reflective of a Living School in ways that are best adapted and relevant to schools’ unique contexts. The process is not designed to be competitive, hierarchical, or formally structured through designations or rankings of any kind.

3. Living School Portraits

By way of illustration and introduction, we have chosen to profile three schools that illustrate many of the attributes and practices described above. It is not intended that these examples be fully described case studies, but that they act as concrete examples of how the Living Schools approach can complement and provide structure and a larger vision for the promising practices already occurring. The goal here is to demonstrate that adopting a Living Schools approach is not to be viewed as an add-on or another ‘thing’ schools feel they are expected to take on. Each of the schools are already meeting many of the key Living School attributes. By providing a coherent vision, these schools can build on the good work they are already engaged in to more fully realize the Living Schools vision. It is not our intent to fully detail the Living Schools framework as this is done in the forthcoming publication O’Brien and Howard (in press),

Living Schools: Transforming Education. We begin with Sigurbjorg Stefansson Early School in Manitoba, Featherston Drive Public School in Ontario, and Randolph Union High School (RUHS) in Vermont. It should be noted that while these schools do not identify formally as Living Schools, they adhere to many of the attributes and practices aligned with the Living School concept (see

Figure 1). These schools were identified through previous research [

18] as pockets of excellence and schools who align with many of the attributes and practices reflected by a Living Schools approach.

Sigurbjorg Stefansson Early School, Manitoba, Canada.

About seven years ago, the principal of Sigurbjorg Stefansson Early School, Rosanna Cuthbert, invited her staff to join her on an exploration of the Reggio Emilia approach to teaching and learning. The local school district had already made a commitment to Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), in line with the province of Manitoba’s ESD strategy, thereby connecting with many of the practices as outlined in the column under Values and Vision. The Reggio student-centreed teaching practices at Sigurbjorg Stefansson Early School rest squarely within

Figure 1. Every day involves outdoor learning and enriched creative teaching practice to engage children in active, participatory learning. For example, each classroom has a Wonder Wagon. The wagons carry supplies for all-day learning treks as well as transporting branches, plants, seeds, rocks, and other items that students bring back to class to investigate further in their “Wonder Books”. The school pays special attention to the physical environment. There are no traditional student desks. Tables of various shapes and dimensions create a feeling of flow. Consciously aiming to reduce plastic and utilize naturally constructed wooden containers and wicker baskets, the school has replaced the ubiquitous storage plastic tubs. Each classroom has unique lighting arrangements of lamps and strings of lights, with limited use of overhead florescent lighting. Each teacher, regardless of grade level taught, is familiar with the learning outcomes for all of the JK-4 grades so that student self-directed learning can be documented, and further growth supported. When needed, specific personalized interventions called provocations gently nudge the student towards meeting outcomes. In every classroom, students are fully engaged—sometimes on their own, with classmates, or in a large group. It was noted by the researchers that a sense of well-being pervades the entire school, though not just student well-being. The principal, Rosanna Cuthbert, noted that one of the unanticipated outcomes of integrating Reggio Emilia and ESD has been enhanced teacher and staff well-being. None of this has come at the expense of measures of academic success [

35]. The description demonstrates an approach that highlights many of the attributes across the framework as presented in

Figure 1.

Featherston Drive Public School, Ottawa, Canada.

There are more than 50 cultures represented at Featherston Drive Public School in Ottawa, Ontario. No doubt this presents some challenges, but the school chooses to celebrate its diversity with a multicultural club scheduled during the school day, reflecting the prominence this has for the K-8 school. In the grade three class, students knowledgeably explain how the class vertical garden works and what they plan to do with the bok choy, basil, lettuce, and a host of other plants. Outside, every grade has a garden box. During a classroom visit by the researchers, the Living School concept was discussed with the third-grade students who readily understood and identified with the attributes of well-being for all, and how their school demonstrates its care for the environment and for other people. The third graders loved the idea that Living Schools are happy schools. When the teacher asked them if they thought Featherston Drive was a Living School the children cheered and clapped their affirmation that their school feels like a Living School to them. During the lunch hour, a senior club of students called Shannen’s Dream gathered to share their experience of supporting the rights of First Nations children to have safe and caring schools. The group had demonstrated on Ottawa’s Parliament Hill on February 14, Have a Heart Day. Prior to our visit, the grade eight class had completed an assignment from Catherine’s sustainable happiness book that involved interviewing the happiest person they knew [

36]. The key lessons they had learned were displayed on a flip chart: happiness comes from connection to community and others; healthy relationships with family and friends, spiritual connections, meaningful work, a principle-centred life, diversity, and connection to the environment. They were beaming when they learned that their interviews reflect the research on happiness and well-being.

Similar to Sigurbjorg Stefansson Early School, a feeling of well-being permeates the halls at Featherston Drive. It is evident in the way staff and students interact, the respect that students display for one another, and also the staff spirit and commitment. The following is an excerpt from a blog by one of the teachers, Tanya O’Brien [

37].

I love my school! This week was a perfect example of one of the many things that make our building the happy place that it is. David, a chef turned teacher, is a man on a mission to bring food and learning together into one big tasty dish for all to share. Students and staff have all benefited from his ideas, energy, and love of people and food… this year David was able to help get a school grant for vertical gardens, making learning through the growth of fresh food a year-round experience.

This week was special as it was “harvest” time. The two classes involved in this cycle were taught about how to harvest and clean their crop, how we taste, what emulsification is, ratios in recipes and how we decide if something tastes balanced…

Spices, herbs, lemons, garlic, hot sauce decorated the tables, carefully labeled for students new to Canada learning new vocabulary... David noted that many of the dressings reflected the cultures from which the students come. Many of our Middle Eastern students chose lemon bases and our Somali students chose spicy ones. The ones I tasted were delicious! This school highlights innovative and engaging practices connecting Teaching and Learning and Health and Well-being. Further growth and development toward a Living Schools approach would come with school staff, parents, students, and administrators looking for opportunities to incorporate nature and Place-based pedagogies and formulating a Vision and values to guide future school growth and development.

Randolph Union High School (RUHS), Randolph, Vermont, USA.

RUHS was awarded the New England Secondary School Consortium (NESCC) and Great School Partnership’s Champion Award for Education Leadership in 2017 for its innovative approaches to career and workforce development. Several years ago, Principals David Barnett and Elijah Hawkes began to transform RUHS into a dynamic, 21st Century learning environment and a Living School that is deeply invested in the economic sustainability of the community while developing young people with the skills and dispositions to find meaningful employment and contribute to the viability of the region. The region is largely rural and struggling with outmigration of youth, ageing demographics, and a lack of employment opportunities. Robert Haynes, Executive Director of the Green Mountain Economic Development Corporation (GMEDC) described RUHS in the following manner:

RUHS has enlightened leadership who have proved they can ‘connect the dots’ among employers, students and their families. Their success at developing apprentice programs with local companies and the Vermont Technical College, as well as other channels for pursuing alternative pathways, makes RUHS true “Poster Children” for an effective 21st Century model. They clearly recognize that the world has changed, and we need to change with it, and their success has led to meaningful conversations in the 30 towns which GMEDC serves. They are a valuable resource I use for work with other secondary school administrators, state educators and economic development staff [

38].

Several years ago, RUHS realized a heightened awareness of how important engaging its Community Economic Development (CED) partners was if it were to create a sustainable, 21st Century learning environment that enabled the well-being of all students. Matt Considine, Director of Investments for the State of Vermont, noted, “a sustainable Vermont economy will benefit from an approach to CED that focuses on a symbiotic relationship among all stakeholders. Critical to the success of that approach would be a better coordination between local school systems and traditional economic development partners” [

39].

In response to a decade of regional economic challenges, RUHS reached out to its traditional CED partners to explore ways to address the challenges it was facing. Three key initiatives that resulted from engaging CED partners included the creation of an off-campus program called the “School of Tech”, the implementation of an on-campus Problem-Based Learning (PBL) laboratory, and the development of an Advanced Manufacturing program.

RUHS represents a school guided by strong leadership, as described by the framework. Teaching and learning align with the requisite Living School attributes that also connect to place and community building. Teachers and administrators of RUHS have key strengths in these areas that can be built upon with strategies designed to move the school to take up the other Living Schools attributes to complement what they already are doing so well. All three initiatives described above began with forging meaningful relationships with local CED partners representing higher education, political leaders, business leaders, and entrepreneurs. The initiatives provide students with experiential learning opportunities that are based in real-life problems and serve to expand teaching and learning beyond the walls of the school. Further, the initiatives required a transformative mode of thinking that cultivates compassion and well-being for all students and, most importantly, enables student voice and agency.

4. Community Partnerships: A New Vision for School Governance and Leadership

The brief illustrative school portraits presented above are representative of the many examples of pockets of excellence alluded to earlier in this paper—the individual schools, teachers, principals, superintendents, and communities that are disrupting the educational status quo by pushing and supporting the attributes of Living Schools through meaningful partnerships with the community. While the schools profiled here are public schools, in many instances, transformative schools are private, or charter schools purposely created to align with a vision of 21st century teaching and learning [

22,

32]. Private and charter schools often have the autonomy and the support to make the changes that reflect their vision. Public schools, on the other hand, confront added challenges in breaking away from the highly resistant administrative structures and the powerful hold of traditional teaching and learning.

Schools do not exist in vacuums; they are part of systems overseen by district and government authorities. Students leave public schools for post-secondary education institutions and employers that exert a powerful influence on assessment approaches—and, by default, the type of teaching and learning that happens in public schools. With schools as parts of interconnected systems, Brooks and Holmes [

5] write, “... lasting, impactful change is best implemented in the larger system. We propose that the components of this larger whole be thought of as an ecosystem, rather than as hierarchies of super structures imposed one on top of the other” (p. 43).

Sustainable and scalable change is necessary to allow the innovation and deeper learning models found in existing pockets of excellence to resonate widely through whole districts and school systems. Shifting public schools to the ethos and vision reflected in a Living Schools attribute framework must be done by influencing the entire ecosystem through mechanisms that include all stakeholders. Preparing students to be creative, connected, and collaborative problem solvers who are healthy human beings committed to the well-being of their communities means making such goals explicit to students, teachers, and parents. It means engaging local employers and post-secondary institutions in discussions that will demonstrate that the vision of a Living School aligns with a new type of learner who is a valuable post-secondary student, employee, entrepreneur, neighbor, and community member.

We propose that this scalable, sustainable change can be nurtured by adopting the principles of Community Economic Development (CED) that are re-conceptualized and closely aligned with the Living School concept. Both call for holistic and interdependent approaches to creating sustainable communities. We also propose transformational governance structures that challenge the status quo in educational leadership and depend on networked approaches to change within a holistic ecosystem. In this vision, local employers, higher education institutions, community groups, students, teachers, parents, and school boards are all partners in collaboratively re-imagining what schooling can become.

4.1. Re-conceptualizing CED

Economic development and community development were historically separate concepts; however, over time, greater collaboration and partnership-building within communities led researchers to integrate these concepts [

40,

41], thereby leading to contemporary approaches to CED.

CED is typically defined as action by people at the local level to create sustainable economic opportunities and to improve social conditions contributing to well-being for all [

42]. CED occurs when people in a community take action and, as a result, local leadership and initiative are then seen as the resources for change [

43]. The Canadian CED Network adds that in order for CED to be successful, solutions must be rooted in local knowledge and led by community members using holistic and integrated approaches. Traditional CED partners include local entrepreneurs, business owners, researchers, and public policy makers working together to support individuals, to build enterprise, and to strengthen communities. Therefore, broadening current CED partnerships to include local school systems is an essential step to realizing sustainable economic growth. Further, re-conceptualizing CED this way will support the repurposing of education toward a transformative sustainability education paradigm.

A holistic approach to Community Economic Development requires stakeholders in various sectors to integrate their efforts in ways that may be unfamiliar and even uncomfortable at first. Too often, leaders in one sector criticize leaders in other domains who might be our most able partners. For example, public schools and colleges are often criticized by the business sector for ineffectively preparing students for the workforce. Higher education is often stereotyped as too theoretical and lacking real world experience. General public trust in both corporations and government has eroded. Likewise, in order to effectively address the economic challenges we face, community leaders need to put aside their distrust and traditional biases and recognize the important contributions and roles each sector has to play in affecting the overall health and sustainability of our local communities.

We propose that sustainable community growth and well-being, scalable education reform, and the leadership responsible for implementing that reform, must reflect the principles and values of sustainability and embody twenty-first century competencies. To enable this transformation, a new vision of educational governance and leadership is required.

4.2. A New Vision of Educational Governance and Leadership

Traditionally, high performing school boards have been recognized for being organized, planned, highly disciplined, and focused on the fundamentals of governance. One of the core challenges facing boards is their failure to use a coherent system of governance [

44], thereby resulting in organizational underperformance or failure. Successful organizations are led by boards that: (1) Know the business at hand, (2) operate within the principles of governance, (3) focus on achieving the organization’s desired outcomes, and (4) effectively manage internal and external relations.

The Canadian Comprehensive Auditing Foundation [

45] identified the following characteristics of effective governance. Board members must have or obtain the necessary skill, knowledge, ability, and commitment to fulfill their responsibilities; understand their organization’s purpose and whose interests they represent; understand the organization’s objectives and strategies to achieve them; know what information they require and obtain that information; act to ensure the organization’s objectives are met, and that the organization’s performance is satisfactory; and be accountable to those they represent.

We question whether these attributes are sufficient to transition our traditional models of school governance with holistic and interdependent approaches to creating sustainable communities. We posit that additional skills and knowledge in governance and policy making must be developed and employed to support successful school transformation into 21st century learning environments.

4.3. Transformational Governance in the 21st Century

In 21st century teaching and learning documents, including high profile reports and whitepapers, issues of governance in the implementation of transformative educational change are rarely addressed [

4,

5,

6,

32]. In fact, school boards have been portrayed as barriers to change and obstructionist in the face of the school’s effort to be autonomous and to chart a course based on a local vision for change. Brooks and Holmes [

5] state schools should be “protected from inappropriate government or school board interference [in] delivering the kinds of learning opportunities for which it was established” (p. 43). Unfortunately, this adversarial relationship thwarts perhaps the most powerful catalyst for scalable, transformative educational change—school districts, superintendents, ministries, and state departments of education that share in a transformative vision and support schools to meet their goals.

Carver stated that “school boards commonly concentrate on the wrong things, exhibiting a tendency to interfere in the details”, and added that educational reform efforts have “for the most part, bypassed local school boards” [

46] (p. 30). For some time now, there has been a growing literature base calling for new governance approaches to be developed [

47,

48]. Expanding our current understanding of governance theory and practice is required for schools to fully participate in sustainable community development. First and foremost, school board trustees must develop a strong understanding of the principles of CED, sustainability, and 21st century learning environments, and become willing to engage community partners in their work. Further, school boards must be open to challenging the nineteenth and twentieth century education structures, approaches, and pedagogies to meet the demands of twenty-first century realities.

In practical terms, how might school boards strive to create an organizational ethos that is aligned with the Living Schools model? School boards need to do their part in creating an organizational culture that enables creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship. School-level leaders, teachers, and students need to be released from current restrictive structures in order to meet these new expectations.

One of the most important responsibilities of governing boards is to inspire the organization through the careful establishment of policies that reflect the values, vision, and desired outcomes of the school system [

49]. School boards traditionally complete this work within the silos of the school board office without soliciting input from community partners. In short, school boards must work to create system-wide values and a vision for education that expects and supports competencies of 21st century learning and the attributes of Living Schools. The values and vision of school districts must explicitly support and encourage the development of experiential learning opportunities for youth that: Engage the real world; develop and expand cultural awareness of diverse world views; include indigenous knowledge and traditions; demonstrate a concern for the living world; develop a compassion for people and all living things as well as the skills to address positive change; promote the health and well-being of all students, staff, the wider community, and natural environment; and commit to a solution-focused growth mindset when facing challenges and opportunities.

The question arises then, how might boards and educational leaders be convinced to take up a Living Schools approach and in doing so connect schools to the life of the community? One positive development in this regard is the growing awareness of the complex issues that face communities, the society at large, and children and youth. Additionally, teachers who exhibit high levels of burn out and leave the profession in increasing numbers. School districts and administrators struggle every day to address the complex needs of their stakeholders. The status quo approach, or viewing issues as disconnected while attempting interventions conceived in silos, has not resulted in the type of responses we need. Administrators and school leaders require educational and professional development opportunities that provide them with the sophisticated skills to change organizations to reflect a commitment to collective values related to sustainability and well-being for all. Next, we describe what these educational and professional development learning opportunities may envision.

5. Preparing Education Leaders for Change: An Integrated, Holistic Approach

Repurposing current educational practices, resources, and outcomes is a critical component of the creation of viable communities that enable well-being for all. This leads to the question of what kind of professional learning is required by current and future education leaders who will be tasked with implementing scalable change that aligns with 21st century learning, and the vision represented by Living Schools. It would stand to reason that transforming schools for 21st century learning requires 21st century leaders—leaders who understand systems thinking, who embrace leading stakeholders toward a shared vision of education that reflects the sustainable well-being of communities, and who appreciate the central role schools can play in the attainment of that vision.

Education leaders typically seek out advanced professional learning specific to education leadership through graduate education programs in the form of master’s degrees in Education Administration and education doctorates. Experienced teachers often move into leadership roles, and through an advanced degree learn the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that equip them to work in diverse leadership roles in the education field. The focus of such graduate education programming is leadership in education organizations, the responsibilities of schools, and the study of organizational structures. Electives drawn from general education courses on curriculum, foundations, law, and theory allow for specialization.

Few educators would envision that their professional learning could be served well in a conventional business school. This is understandable because most business schools offer sound learning experiences for administrators and leaders in the core areas of economics, accounting, finance, marketing, human relations, management analysis, and strategy. Many graduate programs, most commonly Master of Business Administration programs, are organized around these core courses and electives to allow for subject speciality or concentration. They are not applied to education contexts.

However, increasingly, leading transformational change requires sophisticated skills and a deep understanding of organizational dynamics that require skill-sets developed in both business and education schools. Governance, accounting, marketing, community economic development, and management can be tailored to the very unique purposes, objectives, and aims of schools and the structures of school administration. Professional learning that combines the knowledge and skills required by business leaders with the in-depth understanding of implementing new aims and goals of transformative learning has many potential benefits. Likewise, business leaders would benefit greatly from a deeper understanding of how people learn and how to employ differentiated strategies to facilitate improved employee development.

As we consider new models for governance and leadership in education it is valuable to consider that Living Schools, ESD, and new pedagogies required an interdisciplinary approach to real-world learning. Similarly, professional learning initiatives ought to reflect these attributes. Collaborative, advanced business and education administration programming brings future business leaders and education leaders together in professional learning environments—with a shared understanding of sustainability and CED. Such learning experiences would inherently foster common understandings and future collaborations. In a combined business/education leadership program, educators develop an enhanced understanding of business practices aligned with sustainability and community economic development, transformative governance models, accounting practices connected to educational aims and goals, and marketing strategies designed specifically for the requirements of education systems. Future business leaders develop a deeper knowledge and appreciation of the aims and vision of K12 education and collaborative opportunities to advance community sustainability, student career readiness, and understand the interconnections between schools and the future success potential of business enterprises large and small that engage with principals, teachers, and young people in creating 21st century learning opportunities.

Such a professional learning program would support a more robust, holistic ethos of collaboration, creative, and critical problem solving guided by the precepts of systems thinking and experiential learning linked to real-world opportunities to enhance the sustainable well-being of the entire community. The interrelationships between healthy communities, the prospect of meaningful employment, and a highly educated citizenry with career and life skills which contribute to responsibility, empathy, personal health, and well-being is a vision for education in which most people would not find it difficult to share.

To achieve this vision requires a substantial shift in how we come to understand what is required of education leaders. Through a collaborative professional program that coalesces the core business skills and knowledge with a deep understanding of the aims and goals of transformative education and Living Schools, it is possible to point to a powerful way forward in implementing the change we need now and into the future.